A

The Changing Epidemic

AIDS TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES1

The first cases of AIDS were reported in 1981 (CDC, 1981). Through 1999, a total of 733,374 AIDS cases and 430,411 AIDS-related deaths were reported. Approximately 99 percent (724,656) of AIDS cases were reported among adults and adolescents age 13 and older; 1 percent (8,718) were reported among children under the age of 13. In 1999, 46,400 new AIDS cases were reported (CDC, 2000b). Cases reported in the United States account for less than 1 percent of the estimated cases reported worldwide (Text Box A.1).

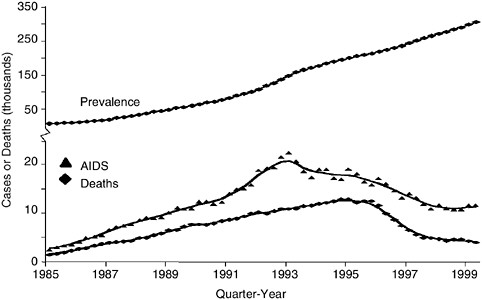

During the first decade of the epidemic, the number of new AIDS cases rose by between 65 percent and 90 percent annually (CDC, 1996).2 In 1996, AIDS incidence3 and AIDS deaths declined for the first time in the history of the epidemic (CDC, 1997) (Figure A.1). These declines can be attributed to advances in antiretroviral therapies that slow disease

|

1 |

This section relies heavily on information contained in “The States of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2000). |

|

2 |

These numbers must be interpreted with caution, however, as the AIDS case definition changed in 1985, 1987, and 1993. |

|

3 |

The expansion of the AIDS case definition in 1993 created a temporary distortion in AIDS trend incidence. By the end of 1996, the temporary distortion caused by reporting prevalent and incident cases that met criteria added in 1993 had almost entirely disappeared. Figure A.1 reflects this distortion in the AIDS incidence trend. |

|

TEXT BOX A.1 In 1999, an estimated 34.3 million people worldwide were living with HIV or AIDS. Since the beginning of the pandemic, AIDS has resulted in more than 18.8 million deaths, including 2.8 million during 1999 alone. More than 95 percent of all HIV-infected people live in the developing world, and approximately 70 percent of all HIV-infected people live in sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2000). The AIDS epidemic is having devastating effects on the social and economic welfare and health of developing nations. The resulting instability, in addition to the public health implications of increased travel and migration, has direct implications for the United States. The Committee suggests these issues be addressed in a future study focused on optimizing the U.S. role in fighting the global pandemic. |

progression and extend the lives of people with AIDS, and in part to the success of earlier HIV prevention efforts (CDC, 1999b). Since mid-1998, however, the number of AIDS cases and deaths diagnosed each quarter has remained relatively stable (CDC, 2000d). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that the stabilization is likely due to a combination of several factors including: treatment failure and the fact that some people have problems adhering to treatment regimens; the fact that HIV prevention efforts have already reached many of those individuals who are most disposed to treatment; and the fact that many people cannot be reached with early testing and treatment (CDC, 2000d).

Between 1993 and 1999, the estimated number of people living with AIDS increased by 69 percent (CDC, 2000b) (Figure A.1). Today, the number of people reported to be living with AIDS4 (299,944) is at an all-time high (CDC, 2000b).

Modes of Transmission

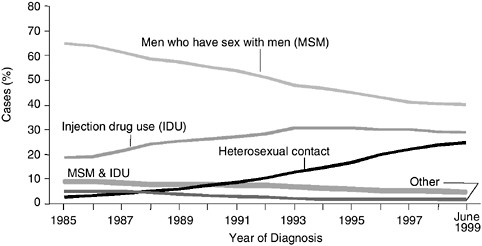

In the United States, the primary modes of HIV transmission have been sexual intercourse and injection drug use. Of the 724,656 AIDS cases reported among adults and adolescents since the beginning of the epidemic, 47 percent have been linked to sex between men, 25 percent to injection drug use, 10 percent to heterosexual intercourse, 6 percent to men who have sex with men and inject drugs, and 2 percent to contaminated blood or blood products (CDC, 2000b). In recent years, however, disease patterns have begun to shift. A declining proportion of new AIDS cases now is being attributed to sex between men, and an increasing proportion of cases is being linked to heterosexual exposure. However, MSM remains the single largest exposure group (CDC, 2000b). The pro-

FIGURE A.1 Estimated AIDS incidence, deaths, and prevalence in adults, quarter-year of diagnosis or death, 1985–1999, United States. SOURCE: CDC, 2000c.

portion of AIDS cases linked to sex between men declined from approximately 65 percent in 1985 to 40 percent in 1998 (CDC, 2000b; CDC, 2000c) (Figure A.2). In contrast, the proportion of AIDS cases linked to heterosexual transmission accounted for less than 5 percent in 1985 but increased to 15 percent in 1999. The proportion of cases linked to injection drug use rose through the early 1990s, but has declined in recent years. Injection drug use accounted for 22 percent of new AIDS cases in 1999 (CDC, 2000b).4

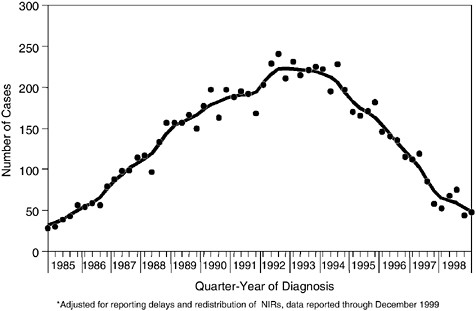

Perinatal transmission is the primary route of HIV infection among children under 13 years of age. With the exception of children infected through transfusions and blood products, which occurred mostly in the early 1980s, the vast majority of children with AIDS (92 percent) were infected in the course of pregnancy, delivery, or breast feeding (IOM, 1999). In the early 1990s, roughly 1,000 children were diagnosed with

FIGURE A.2 Adult/adolescent AIDS cases by exposure category and year of diagnosis, 1985–June 1999. SOURCE: CDC, 2000c.

AIDS each year (Figure A.3). One of the greatest successes in HIV prevention occurred with the 1994 finding that administration of the antiretroviral drug zidovudine during pregnancy and childbirth could reduce the chances of perinatal transmission by two-thirds (Connor et al., 1994). The rapid implementation and use of zidovudine and other antiretroviral drugs in clinical settings, combined with efforts to identify and treat HIV-infected pregnant women through HIV screening in prenatal care settings, led to dramatic declines in the number of pediatric AIDS cases (Figure A.3). Between 1993 and 1999, the number of pediatric AIDS cases declined by 75 percent (CDC, 2000b).

The Changing Demographic Face of the Epidemic

The demographic populations affected by the epidemic have evolved over time. During the 1990s, women, youth, and racial and ethnic minorities accounted for a growing proportion of new AIDS cases. Geographic distributions have also shifted, with a growing proportion of cases emerging in rural and smaller urban areas.

AIDS Cases in Women

The increases in AIDS cases among women is consistent with the increase of cases linked to heterosexual transmission. The proportion of annual new AIDS cases among women tripled, from 7 percent to 23 per-

FIGURE A.3 Perinatally acquired AIDS cases by quarter-year of diagnosis, 1985–1998, United States. SOURCE: CDC, 2000e.

cent, between 1986 and 1999 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2000). Women now comprise 17 percent of the total AIDS cases reported since 1981, and 20 percent of the population living with AIDS (CDC, 2000b).

Women in racial and ethnic minority groups have been disproportionately affected by the epidemic. In 1999, 81 percent of new AIDS cases among women were reported among Hispanic and African-American women. These women represented 23 percent of the U.S. population of women (U.S. Census Bureau, 1999). The AIDS case rate among African-American women (49.0 per 100,000) was more than 20 times the rate among Caucasian women (2.3 per 100,000), while the rate among Hispanic women (14.9 per 100,000) was more than six times the rate among Caucasian women (CDC, 2000b).

AIDS Cases in Youth

AIDS has had a major impact on teenagers and young adults. In 1998, AIDS was the ninth leading cause of death among youth ages 15–24, and the fifth leading cause of death among individuals 25–44, many of whom were infected as teenagers (Murphy, 2000). Young women, and particularly members of racial and ethnic minorities have been disproportion-

ately affected. In 1999, females accounted for 58 percent of reported AIDS cases among 13- to 19-year-olds and 38 percent of cases among 20- to 24-year-olds. Almost half of the new AIDS cases in the 13–24 age group (43 percent) were among African Americans, and almost one-quarter (21 percent) were among Hispanics (CDC, 2000b).

Sexual exposure is the primary route of infection among young people. Most young men are infected through sex with other men, while most young women are infected through heterosexual exposure. In 1999, 50 percent of AIDS cases among males ages 13–24 were acquired through sex with other men, and 8 percent through sex with women. In the same year, nearly half of new AIDS cases (47 percent) among females ages 13–24 were acquired heterosexually. Furthermore, a proportion of “risk not specified” cases would fall into these risk exposure categories if the data were available (CDC, 2000b).5

AIDS Cases in Racial and Ethnic Minorities

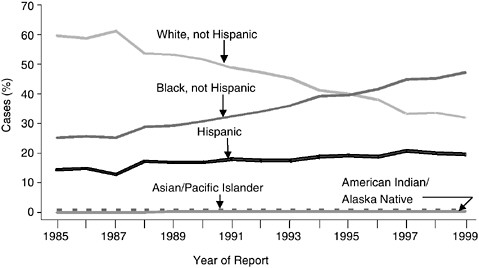

Racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans and Hispanics, have been disproportionately affected by the AIDS epidemic. The proportion of new cases among African Americans and Hispanics has increased over time, while the proportion of AIDS cases among Caucasians has decreased. Since 1996, African Americans have accounted for a greater proportion of AIDS cases than Caucasians. The proportion of cases has remained relatively stable in American Indians and Asian/Pacific Islanders. These two groups comprise approximately one percent of all AIDS cases (CDC, 2000b; CDC, 2000a) (Figure A.4).

Although African Americans and Hispanics, taken together, accounted for 66 percent of all new AIDS cases in 1999 (CDC, 2000b), these groups comprised only an estimated 23 percent of the total U.S. population (CDC, 2000a). In 1999, the AIDS case rate6 among African Americans (66.0 per 100,000) was more than eight times the rate among Caucasians (7.6 per 100,000), while the AIDS case rate among Hispanics (25.6 per 100,000) was three times higher than for Caucasians (CDC, 2000b).

While the number of AIDS-related deaths has declined7 among all racial and ethnic groups, the decline has been slower among African Americans and Hispanics. AIDS remains the leading cause of death among African Americans between the ages of 25 and 44, and the third

FIGURE A.4 Proportion of AIDS cases, by race/ethnicity and year of report, 1985–1999. SOURCE: CDC, 2000a.

leading cause of death among Hispanics in this age group. Among Caucasians of the same age group, AIDS is the fifth leading cause of death (Murphy, 2000). In 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, the death rate from AIDS for African Americans (32.5 per 100,000) was nearly 10 times the rate among Caucasians (3.3 per 100,000) (Gayle, 2000).

Geographic Distribution of AIDS Cases

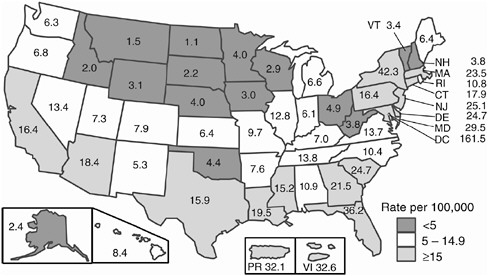

AIDS cases have been reported in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories. Ten states and territories account for almost three-quarters (72 percent) of all AIDS cases.8 Four states—New York, California, Florida, and Texas—represent 52 percent of cumulative AIDS cases and 47 percent of new AIDS cases reported in 1999, yet these states contain only 32 percent of the U.S. population (CDC, 2000b; U.S. Census Bureau, 1999). In 1999, the states and territories with the highest AIDS incidence rate 100,000 population were the District of Columbia (161.5 cases per 100,000 population), New York (42.3 cases per 100,000 population), Florida (36.2 cases per 100,000 population), Puerto Rico (32.1 cases

per 100,000 population), and Maryland (29.5 cases per 100,000 population) (see Figure A.5). These figures compare with the national AIDS incidence rate in 1999 of 16.7 cases per 100,000 population (CDC, 2000b).

Historically, AIDS cases have been largely concentrated in urban areas. In 1999, 79 percent of AIDS cases were diagnosed in metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more. Ten metropolitan areas (New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, Newark, and Atlanta) accounted for almost half of the cumulative reported AIDS cases. In terms of new AIDS cases per 100,000 persons, the most heavily affected metropolitan areas in 1999 were New York City (72.7 per 100,000), Miami/Ft. Lauderdale (65.3 and 61.2 per 100,000, respectively), Columbia, S.C. (54.6 per 100,000), and San Francisco (50.8 per 100,000) (CDC, 2000b).

While the U.S. epidemic has been perceived largely as an urban phenomenon, AIDS cases in rural areas have been among the most rapidly rising subset of the new cases reported to the CDC. The fastest growing rural epidemic is in the South, followed by the Northeast, the West, and the Midwest. As a proportion of the total cases, heterosexual transmission is more common in small town/rural settings than in urban sites; women and racial and ethnic minorities represent a substantial subset of nonurban cases (Wortley and Fleming, 1997; Graham et al., 1995).

FIGURE A.5 AIDS case rates per 100,000 population, reported in 1999 (CDC, 2000c).

AIDS and Co-Occurring Conditions

AIDS is often part of an overlapping cluster of epidemics. AIDS cases are increasingly concentrated in disadvantaged populations that have high rates of poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and inadequate access to health care. AIDS also overlaps with other illnesses, including drug addiction, mental disorders, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), tuberculosis (TB), and hepatitis. These conditions may contribute to the risk of HIV exposure and transmission and may complicate HIV prevention and therapeutic efforts.

AIDS has had a disproportionate impact on the poor and disadvantaged populations. Over the course of the epidemic, there has been a steady increase in the numbers of HIV-infected persons who are homeless and marginally housed (Bangsberg et al., 2000; Zolopa et al., 1994). Many of these individuals lack access to necessary health services, including primary medical care, substance abuse treatment, and HIV care (including treatment with new antiretroviral therapies) (Acuff et al., 1999). Recent studies suggest that poverty contributes to HIV infection risk in several ways. Socioeconomic instability may contribute to higher rates of prostitution, drug use, incarceration, and family disruption, all of which are linked to the spread of HIV (Fournier and Carmichael, 1998).

The link between substance abuse and risk of HIV infection is well-established (IOM, 1997; NRC and IOM, 1995; NRC, 1989). Injection drug users are primarily infected through sharing of contaminated injection equipment, which acts as a vector for HIV-infected blood (NRC and IOM, 1995). HIV infection among injection drug users also poses a threat to their sexual partners and children (NRC and IOM, 1995). Use of non-injection drugs (e.g., alcohol, crack cocaine, methamphetamines, and inhalants) also can impair decision-making, thereby increasing the likelihood of HIV transmission and infection through high-risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex or trading sex for drugs) (IOM, 1997). Immunosuppression caused by long-term use of alcohol and drugs increases the likelihood of infection and, among infected persons, increases the development of AIDS-related opportunistic illnesses (Acuff et al., 2000).

Mental illness also can increase HIV infection and transmission risk (Diamond and Buskin, 2000; Marks et al., 1998). Although some mental disorders may exist prior to the HIV diagnosis (e.g., depression and personality disorders), others may develop during the course of the disease (e.g., HIV-associated dementia). Serious mental illness increases the likelihood of high-risk sexual behaviors or substance abuse, and thus may contribute to treatment nonadherence. Individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) often experience high rates of unemployment, poverty, and homelessness, which can increase the com-

plexity associated with preventing and treating their HIV disease (Rabkin and Chesney, 1999; Susser et al., 1995; Susser et al., 1997a; Susser et al., 1997b).

The presence of sexually transmitted diseases may increase both susceptibility to HIV infection and the infectiousness of people who already have HIV. Epidemiological studies suggest that people may be two to five times more likely to become HIV-infected when other STDs are present (Levine et al., 1998; Patterson et al., 1998; IOM, 1997). Similarly, studies suggest that for HIV-infected individuals, the presence of another STD infection increases the likelihood of transmitting HIV to sexual partners (e.g., through genital lesions or increased concentration of HIV in genital secretions) (Cohen et al., 1997; CDC, 1998a).

HIV also overlaps with the spread of other diseases, including TB and hepatitis B and C. Because HIV infection suppresses the body’s immune system, HIV-infected persons are at increased risk of developing TB and, if infected, are 100 times more likely to progress to active TB than those not infected with HIV. The CDC estimates that 10 to 15 percent of all TB cases, and 30 percent of cases among individuals age 25 to 44, occur among HIV-infected individuals (CDC, 1998b). Moreover, a recent study found that common HIV and TB treatments may be incompatible (Spradling, 2000). In addition, because HIV-infection accelerates the progression of liver disease and cirrhosis that hepatitis C causes, co-infected individuals may have limited tolerance for antiretroviral therapy, as many of the drugs have hepatic side effects (Ostrow, 1999).

HIV INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

In contrast to the epidemiology of AIDS, less is known about either the incidence and prevalence of HIV, or about the geographical, racial, or age distribution of infections. Estimates of HIV incidence and prevalence can be derived from a number of sources, although none provide a complete or accurate picture of true HIV incidence or prevalence. First, statistical estimates can be made by reverse calculations (“back calculations”) from reported AIDS cases, incorporating established patterns of disease progression (Brookmeyer and Gail, 1994). Recent developments in therapy for HIV and AIDS have at least temporally decoupled HIV infection and its progression to AIDS (Hammer et al., 1996; Collier et al., 1996). As a result, the timing of the progression from HIV infection to AIDS and from AIDS to death is increasingly difficult to predict, making HIV incidence and prevalence estimates based on AIDS cases much less accurate (CDC, 1999a). Estimates can also be derived from the growing number of states that have made HIV a reportable disease (CDC, 1999a). The accuracy of these data is limited, however, due to biases in the re-

ported data (i.e., only individuals who seek or are offered testing are reflected) (See Chapter 2). The distribution of HIV incidence and prevalence (e.g., by risk groups, race, geography, or age) can also be derived from ongoing cohort studies (e.g., the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study of gay men) (Kaslow et al., 1987). Finally, estimates can be derived from CDC’s family of seroprevalence surveys, including: (1) screening results of blood samples derived from programs testing special populations (e.g., blood donors and applicants to military service and Job Corps), and (2) testing of anonymous blood specimens from smaller studies (e.g., from STD clinics, drug treatment centers, adolescent medical clinics) (Pappaioanou et al., 1990). However, because these studies rely on convenience samples, they cannot be used to produce population-based estimates of HIV incidence and prevalence.

None of these methods or sources of data, however, provides complete and accurate population-based estimates of HIV incidence and prevalence, or of the demographic and geographic distribution of these figures. As discussed in Chapter 2, a new surveillance system, focused on HIV incidence, is needed in order to more effectively guide prevention planning, resource allocation, and evaluation decisions at the national, state, and local levels.

REFERENCES

Acuff C, Archambeault J, Greenberg B, Hoeltzel J, McDaniel JS, Meyer P, Packer C, Parga FJ, Pillen, MB, Rondhovde A, Saldarriaga M, Smith MJ, Stoff D, Wagner D. 1999. Mental Health Care for People Living with or Affected by HIV/AIDS: A Practical Guide. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute.

Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, Bamberger JD, Chesney MA, Moss A. 2000. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS 14(4):357–366.

Brookmeyer R and Gail MH. 1994. AIDS Epidemiology: A Quantitative Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000a. HIV/AIDS Surveillance by Race/ Ethnicity. Slide sets available on the web: www.cdc.gov/hiv/graphics/minority.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000b. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 1999 11(2).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000c. HIV/AIDS Surveillance—General Epidemiology. Slide sets available on the web: www.cdc.gov/hiv/graphics/surveill.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000d. U.S. AIDS Cases, Deaths, and HIV Infections Appear Stable. AMA Press Briefing, July 8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000e. HIV/AIDS Surveillance—Perinatal. Slide sets available on the web: www.cdc.gov/hiv/graphics/perinatal.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1999a. Guidelines for national human immunodeficiency virus case surveillance, including monitoring for human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(RR-13):1–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1999b. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, Mid-year 1999:11(1).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1998a. HIV prevention through early detection and treatment of other sexually transmitted diseases—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 47(RR–12):1–24.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 1998b. Prevention and treatment of tuberculosis among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Principles of therapy and revised recommendations. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 47(RR-20).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1997. Update: trends in AIDS incidence—United States, 1996. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 46:861–867.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1996. 1996 HIV/AIDS Trends Provide Evidence of Success in HIV Prevention and Treatment. Press Release, June.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1981. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 30(21):250–252.

Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, Kazembe P, Dyer JR, Daly CC, Zimba D, Vernazza PL, Maida M, Fiscus SA, Eron J, Jr. 1997. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet 349:1868–1873.

Collier AC, Coombs RW, Schoenfeld DA, Bassett RL, Timpone J, Baruch A, Jones M, Facey K, Whitacre C, McAuliffe VJ, Friedman HM, Merigan TC, Reichman RC, Hooper C, Corey L. 1996. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection with saquinavir, zidovudine, and zalcitabine. AIDS Clinical Trials Group. New England Journal of Medicine 334(16):1011–1017.

Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O’Sullivan MJ, VanDyke R, Bey M, Shearer W, Jacobson RL, Jimenez E, O’Neill E, Bazin B, Delfraissy JF, Culnane M, Coombs R, Elkins M, Moye J, Stratton P, Balsley J. 1994. Reduction of maternal–infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 331(18):1173–1180.

Diamond C, Buskin S. 2000. Continued risky behavior in HIV-infected youth. American Journal of Public Health 90:115–118.

Fournier AM, Carmichael C. 1998. Socioeconomic influences on the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus infection: the hidden risk. Archives of Family Medicine 7:214–217.

Gayle HD. 2000. The State of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Congressional Staff Briefing. Washington, DC, April 3.

Graham RP, Forrester ML, Wysong JA, Rosenthal TC, James PA. 1995. HIV/AIDS in the rural United States: Epidemiology and health services delivery. Medical Care Research and Review 52(4):435–452.

Hammer SM, Katzenstein DA, Hughes MD, Gundacker H, Schooley RT, Haubrich RH, Henry WK, Lederman MM, Phair JP, Niu M, Hirsch MS, Merigan TC. 1996. A trial comparing nucleoside monotherapy with combination therapy in HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts from 200 to 500 per cubic millimeter. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 175 Study Team. New England Journal of Medicine 335(15):1081–1090.

Institute of Medicine. 1997. The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Eng T and Butler W (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine. 1999. Reducing the Odds: Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV in the United States. Stoto MA, Almario DA, and McCormick MC (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). June 2000. Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic. New York: United Nations

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2000. The State of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Capitol Hill Briefing Series on HIV/AIDS.

Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR Jr. 1987. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. American Journal of Epidemiology 126(2):310–318.

Levine WC, Pope V, Bhoomkar A, Tambe P, Lewis JS, Zaidi AA, Farshy CE, Mitchell S, Talkington DF. 1998. Increase in endocervical CD4 lymphocytes among women with nonulcerative sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Infectious Diseases 177:167–174.

Marks G, Bingman C, Duval TS. 1998. Negative affects and unsafe sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS and Behavior 2(2):89–99.

Murphy SL. 2000. Deaths: Final Data for 1998. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

National Research Council. 1989. AIDS: Sexual Behavior and Intravenous Drug Use. Turner CF, Miller HG, and Moses LE (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. 1995. Preventing HIV Transmission: The Role of Sterile Needles and Bleach. Normand J, Vlahov D, and Moses LE (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Ostrow D. 1999. Practical prevention issues. In Ostrow D and Kalichman S (Eds.). Psychosocial and Public Health Impacts of New HIV Therapies. New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers.

Pappaioanou M, Dondero TJ Jr, Petersen LR, Onorato IM, Sanchez CD, Curran JW. 1990. The family of HIV seroprevalence surveys: Objectives, methods, and uses of sentinel surveillance for HIV in the United States. Public Health Reports. 105(2):113–119.

Patterson BK, Landay A, Andersson J, Brown C, Behbahani H, Jiyamapa D, Burki Z, Stanislawski D, Czerniewski MA, Garcia P. 1998. Repertoire of chemokine receptor expression in the female genital tract: Implications for human immunodeficiency virus transmission. American Journal of Pathology 153(2):481–490.

Rabkin JG and Chesney MA. 1999. Treatment adherence to HIV medications: The Achilles heel of new therapeutics. In Ostrow D and Kalichman S (Eds.). Psychosocial and Public Health Impacts of New HIV Therapies. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Spradling P. 2000. Concurrent use of rifabutin and HAART: Evidence for reduced efficacy? (Abstract TUOR B8277). XIII International AIDS Conference. July 9–14, 2000, Durban, South Africa.

Susser E, Betne P, Valencia E, Goldfinger SM, Lehman AF. 1997a. Injection drug use among homeless adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 87(5):854–856.

Susser E, Colson P, Jandorf L, Berkman A, Lavelle J, Fennig S, Waniek C, Bromet E. 1997b. HIV infection among young adults with psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(6):864–866.

Susser E, Valencia E, Miller M, Tsai WY, Meyer-Bahlburg H, Conover S. 1995. Sexual behavior of homeless mentally ill men at risk for HIV. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(4):583–587.

U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1999 (119th edition). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Wortley PM, Fleming PL. 1997. AIDS in women in the United States: Recent trends. Journal of the American Medical Association 278:911–916.

Zolopa AR, Hahn JA, Gorter R, Miranda J, Wlodarczyk D, Peterson J, Pilote L, Moss AR. 1994. HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco’s homeless adults. Prevalence and risk factors in a representative sample. Journal of the American Medical Association 272:455–461.