7

Overcoming Social Barriers

Although major accomplishments have been made in HIV prevention over the past 20 years, a number of unrealized opportunities to avert new infections still exist. These missed opportunities derive from underlying social and political barriers that have acted as constraints to the objective of preventing as many new infections as possible. Among the most pernicious of the social barriers are poverty, racism, gender inequality, AIDS-related stigma, and society’s reluctance to openly address sexuality. Other important barriers have been the lack of leadership by political and national leaders in galvanizing efforts to combat the epidemic, as well as misperceptions about HIV/AIDS among many people at risk for becoming infected. These barriers have had a profound effect on the course of the HIV epidemic by influencing risk behaviors and by promoting a social context in which HIV transmission is likely to occur. The barriers also have had a fundamental bearing on public policy decisions regarding funding, research, and treatment, and they have influenced decisions about which prevention programs are implemented, the mechanisms by which they occur, and the populations targeted.

The Committee believes that while these entrenched barriers cannot be easily overcome, they must nevertheless be explicitly acknowledged in HIV prevention efforts. The Committee also believes that specific policies and laws emanating from these social and political conditions and attitudes can and must be changed. In this chapter, we describe the barriers that influence the epidemic, and we identify four specific instances in

which these conditions and attitudes have resulted in public policies that run counter to scientific knowledge about effective HIV prevention.

SOCIAL BARRIERS

Poverty, Racism, and Gender Inequality

There is considerable evidence that social inequalities defined by income, race, ethnicity, and gender are key elements in the social contexts and environments that contribute to HIV infection risk. These contextual forces can act at the individual level, when life circumstances such as homelessness or drug use increase the likelihood of high-risk behaviors. The forces also can act at the societal level (Henderson, 1988). For example, economic inequalities between women and men can affect women’s perceptions of their ability to negotiate safe sex practices in a social relationship. Similarly, racism—both historically and in its contemporary forms—has resulted in assaults on the economic opportunities and the self-identity of racial and ethnic minorities, and has implications for Americans’ receptivity to HIV prevention efforts. Moreover, social inequalities create conditions that make it difficult for individuals and communities to even focus on the problem of HIV, since other problems may seem more immediate (e.g., housing, employment). Better understanding these societal forces is critical to achieving the objective of preventing as many new infections as possible.

Increasingly, the metropolitan areas that are most severely affected by HIV/AIDS are also areas of social and political neglect. Individuals living in these disenfranchised environments have increased exposure to a variety of social and psychosocial factors (e.g., poverty, stress, disrupted family structures, insufficient social supports, and toxic environmental exposures) that have demonstrated associations with morbidity and mortality (Geronimus, 2000). Further, inadequate access to health care and lack of supportive, culturally appropriate social services allow co-occurring conditions—such as substance abuse, mental illness, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and violence—to flourish, thus forming epidemiological clusters for a wide variety of concurrent health and social problems (NRC, 1993). Moreover, the higher prevalence of drug trade in impoverished neighborhoods increases the likelihood of exposure to and use of drugs, such as heroin, crack, and cocaine, that are linked to HIV risk (Zierler and Krieger, 1997). These findings are consistent with studies documenting the correlation between economic deprivation and overall AIDS incidence at the state level (Zierler et al., 2000) and in major metropolitan areas (Fordyce et al., 1998; Simon et al., 1995; Hu et al., 1994; Fife and Mode, 1992).

Given that racial and ethnic minority groups are also over-represented among those with HIV/AIDS (see Appendix A; CDC, 2000a), the added burden of coping with societal racism further complicates the implementation of HIV prevention efforts, especially in urban communities. In many urban areas, a legacy of discriminatory social policies (e.g., racially biased mortgage practices, siting of public housing projects and transportation routes) has resulted in a concentration of racial and ethnic minorities in neighborhoods isolated from the social and health care infrastructures needed to preserve health (Cohen and Northridge, 2000; Gerominus, 2000). In addition, racism in the health care setting can pose a major barrier to engaging members of racial and ethnic minority groups in care and prevention efforts (Bayne-Smith, 1996). In one survey of racial and ethnic minorities, 98 percent of respondents reported experiencing some type of racial discrimination within the past year, and 55 percent reported discrimination by health care professionals (Landrine and Klonoff, 1997). Historical accounts of racism in the medical establishment (e.g., the Tuskegee Syphilis Study) have fostered a lack of trust in the modern health care system among some minority groups (Thomas and Quinn, 1991). For example, a recent survey found that 27 percent of African-American respondents believed that HIV/AIDS is a government conspiracy against their racial group (Klonoff and Landrine, 1999). The distrust and fear derived from racist experiences and historical traumas have serious implications for carrying out effective HIV prevention and treatment activities in minority communities. If prevention efforts are to succeed in reaching racial and ethnic minorities, then they must take into account the impact of racism and explicitly address these types of concerns in developing scientifically sound, ethnically appropriate, and culturally acceptable interventions (Thomas and Quinn, 1991).

Over the past two decades, women have represented a steadily increasing proportion of AIDS cases (see Appendix A; CDC, 2000a). Because a substantial and increasing proportion of women are infected through heterosexual contact, HIV prevention strategies broadly targeted to women have stressed women’s negotiation skills in sexual decision making as a way to change male behavior, rather than targeting male behavior directly. This strategy assumes, however, that women have control in sexual decision making and that relations between the genders are equal, which is often not true (Campbell, 1995).

In many cases, gender inequality and the consequences that can derive from it (e.g., domestic violence, fear of abandonment) contribute to a social environment in which a woman may be either unable or unwilling to negotiate consistent condom use or lower-risk sexual practices (Zierler and Krieger, 1997). In extreme instances, initiating discussions of condom use and risk reduction may lead to physical or sexual abuse (Lurie et al.,

1995). Gender inequality may be extreme for drug-addicted women and for those whose partners use drugs, as a large proportion of these women report histories of childhood or adult sexual abuse (Walker et al., 1992; Cohen et al., 2000). In fact, there is a growing body of evidence linking childhood or adolescent sexual abuse to behavioral sequelae that increase risk for HIV infection in adulthood (Zierler and Krieger, 1997). In addition, for some women, sexual risk behavior may be tied to practices (e.g., commercial sex work) that ensure economic survival for themselves and their families. For these reasons, it is essential to acknowledge that gender inequality affects many women and must be taken into account when creating prevention messages for women.

The Sexual “Code of Silence”

Society’s reluctance to openly confront issues regarding sexuality results in a number of untoward effects. This social inhibition impedes the development and implementation of effective sexual health and HIV/ STD education programs, and it stands in the way of communication between parents and children and between sex partners (IOM, 1997b). It perpetuates misperceptions about individual risk and ignorance about the consequences of sexual activities and may encourage high-risk sexual practices (Gerrard, 1982, 1987). It also impacts the level of counseling training given to health care providers to assess sexual histories, as well as providers’ comfort levels in conducting risk-behavior discussions with clients (ARHP and ANPRH, 1995; Risen, 1995; Makadon and Silin, 1995; Merrill et al., 1990). In addition, the “code of silence” has resulted in missed opportunities to use the mass media (e.g., television, radio, printed media, and the Internet) to encourage healthy sexual behaviors (IOM, 1997b; NRC, 1989). The media can be powerful allies in promoting knowledge about HIV and other STDs, and in fostering behavioral change that can reduce the chances of acquiring these diseases (STD Communication Roundtable, 1996). For example, while both children and adolescents are constantly exposed to—and particularly vulnerable to—explicit and implicit sexual messages in various media, the presence of prevention messages (e.g., use of condoms) in the media is practically nonexistent (Lowry and Shidler, 1993; Harris and Associates, 1988). Further, because many adolescents are not receiving accurate information regarding drugs, STDs, and healthy sexual behavior from their parents or other trusted adult sources, they often rely on the media as a primary source of information (STD Communication Roundtable, 1996). Given the impact of media on young people’s attitudes, as well as on consumer behavior, messages that consistently promote risk reduction could facilitate much-needed changes in social norms regarding sexual behaviors and drug-use practices.

|

TEXT BOX 7.1 The Hidden Epidemic made two major recommendations in terms of developing a new social norm of sexual behavior as the basis for long-term prevention of STDs. These recommendations are:

|

In order to address the public’s reluctance to openly confront and discuss sexuality and sexual health, the Committee wishes to acknowledge and endorse recommendations from a prior Institute of Medicine report, The Hidden Epidemic, which aimed to catalyze social change by encouraging discussion of these issues and by promoting balanced mass media messages (IOM, 1997b). Specifically, the report called for a significant national campaign to foster social change that would lead to a new norm of healthy sexual behavior. This campaign would make extensive use of the media to promote comprehensive public health messages regarding STDs, HIV infection, sexual abuse, and unintended pregnancy (Text Box 7.1). The strategies set forth in The Hidden Epidemic recommendations, if they were implemented, would constitute significant steps toward changing social and cultural norms and beliefs about sex.

Stigma of HIV/AIDS

Since the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, people living with HIV or AIDS have been the targets of stigma and discrimination. Despite two decades of public education, prevention efforts, and passage of protective legislation, AIDS-related stigma continues to be a serious problem (Herek, 1999). AIDS stigma is manifested through discrimination and social ostracism directed against individuals with HIV or AIDS, against groups of people perceived to be likely to be infected, and against those

individuals, groups, and communities with whom these individuals interact (Herek and Capitanio, 1998).

AIDS stigma is closely linked to other existing social prejudices, including prejudice against homosexuals and drug users. The initial identification of HIV/AIDS among these marginalized groups has had a lasting impact on the way in which the disease is perceived by the American public. Throughout the 1980s, many people closely associated the AIDS epidemic with homosexual behavior and, although the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS has changed considerably, most heterosexual adults continue to associate AIDS with homosexuality or bisexuality (Herek and Capitanio, 1999). In a 1997 survey, 45 percent of respondents thought that a healthy man could get AIDS by having sex with another uninfected man (Herek and Capitanio, 1999). The public also assigns more blame to people who contract HIV/AIDS through behavior that is perceived as controllable (e.g., sex, sharing needles). In the same 1997 survey, 98 percent of respondents felt sympathy for a person who contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion, while only 58 percent felt sympathy for someone who has contracted the virus through homosexual contact (Herek and Capitanio, 1999). Similarly, AIDS-related stigma has combined with stigma of drug use to affect public policy about HIV prevention programs that target injection drug users (IDUs). For instance, there continues to be strong opposition to needle exchange programs, despite strong evidence of their efficacy (Herek et al., 1998).

In the United States, a significant minority of the public has expressed consistently negative attitudes toward persons living with AIDS and has supported blatantly stigmatizing and punitive measures against them (Herek, 1999). Such actions have helped foster widespread public stigma toward those who are HIV-infected or even perceived to have AIDS, resulting in overt discriminatory practices (such as denial of housing or employment), violence, social prejudice, and moral judgments (Herek and Glunt, 1988; Herek and Capitanio, 1998). Fortunately, support for such measures has declined over time. A national survey conducted in 1991 found that 36 percent of the population supported quarantines for HIV-infected persons and 30 percent supported public disclosure of the names of infected persons; the same survey conducted in 1997 found that these percentages had dropped to 17 percent and 19 percent, respectively (Herek and Capitanio, 1998). Further, the 1997 survey indicated that the majority (77 percent) of respondents believed that people with AIDS are unfairly persecuted in our society (Herek and Capitanio, 1998).

However, there are disturbing trends, too. Compared to 1991, more respondents agreed that people who acquired AIDS through sex or drug use got what they deserved (29 percent in 1997 versus 20 percent in 1991). Similarly, the proportion of the public that believes casual social contact

might lead to HIV infection has increased somewhat (Herek and Capitanio, 1998). In 1991, 55 percent of respondents believed it was possible to contract AIDS from using the same drinking glass (compared with 48 percent in 1991), and 54 percent believed that AIDS might be transmitted through a cough or sneeze (compared to 45 percent in 1991).

AIDS stigma has serious implications for carrying out effective prevention efforts. At-risk or HIV-infected individuals who fear stigmatization or being labeled as part of a stigmatized social group may be reluctant to admit risk behaviors, to seek or find relevance in prevention information, to obtain antibody testing, or to access health care services (Chesney and Smith, 1999; Herek, 1999). These factors can increase the likelihood of continuing risk behaviors, becoming infected, and transmitting the virus to others (Herek et al., 1998).

Thus, while some progress has been made in reducing AIDS stigma, and while public support for discriminatory policies has diminished, AIDS stigma still persists and continues to undermine HIV prevention efforts. As a result, the Committee believes that the protection of human rights, privacy, and equity continues to be a significant concern, and that concurrent efforts at the federal, state, and local level to remove or at least lessen the impact of stigma and discrimination are necessary. In this belief, the Committee states its unflinching commitment to the protection of the rights of those living with HIV/AIDS and those at risk for HIV.

Misperceptions

In addition to the social conditions and attitudes that impede HIV prevention efforts, many people at risk for becoming infected have a variety of misperceptions about HIV/AIDS that hinder the effectiveness of prevention efforts. Several studies have shown that individuals often underestimate or misperceive their risk of acquiring HIV (Mays and Cochran, 1988; Schieman, 1998; Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999a) and STDs (IOM, 1997b), which can lead to an increase in risk behaviors. This misperception is driven, in large part, by the complexity of exposure to HIV: the uncertainty of exposure, the low probability of infection per encounter, the time interval between infection and clinical manifestation of HIV, and the emotional reaction to the severity of AIDS (Poppen and Reisen, 1997). Studies have shown that general knowledge about HIV does not necessarily predict practice of preventive behaviors (Mickler, 1993). Even when individuals are worried about contracting HIV, their perception of the likelihood of actually contracting HIV often is relatively low (Dolcini et al., 1996; Ford and Norris, 1993). Individuals who do not consider themselves to be in “high-risk groups” perceive themselves at low risk and thus engage in riskier behaviors (Dolcini et al., 1996; Mickler,

1993; Lewis et al., 1997). Another belief that influences individuals’ risk behavior is their misperception about HIV-infected people. For example, some individuals believe that anyone who “looks healthy” must not have AIDS, which may lead these individuals to be falsely confident in selecting partners (Ford and Norris, 1993). Finally, the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS can affect the perception of high-risk behavior. People who engage in high-risk activities believed to be behaviorally irresponsible, such as injecting drugs or having unprotected sex, may dissociate from their own behaviors and rationalize that they are not at risk for contracting HIV (Poppen and Reisen, 1997).

The success of combination antiretroviral therapies, along with the emphasis on vaccine development, has also led some people to believe that they no longer need to take precautions against transmitting or acquiring HIV. For example, in a study of HIV-negative or untested persons at risk, 17 percent reported that they were less careful about sex and drug use, and 31 percent were less concerned about becoming infected, because of new treatments (Lehman et al., 2000). In addition, recent studies indicate that treatment advances may have contributed to a resurgence in high-risk behaviors, particularly unprotected sex, as demonstrated by the increased incidence of STDs in San Francisco (CDC, 1999a), Seattle (CDC, 1999b; Williams et al., 1999), Los Angeles, and Philadelphia (Marquis, 2000), particularly among men who have sex with men.

Lack of Leadership

Concerted efforts by politicians and national leaders to openly discuss HIV and engage the public in HIV prevention efforts can set the stage for a national-level mobilization against the epidemic. The Committee believes that such high-level political commitment is necessary for developing a coherent strategy for responding to the epidemic and for providing leadership and direction to other public and private partners, such as federal, state, and local government agencies, community-based organizations, advocacy organizations, researchers, health care providers, the media, and affected communities. While several studies have made recommendations to resolve the interagency1 and intraagency2 co-

ordination and leadership problems at the federal level, the nation still lacks the federal leadership and integration of prevention activities necessary to effectively address the epidemic (CDC Advisory Committee, 1999; PACHA, 2000).

Although there are difficulties in developing coordinated public and private-sector leadership for prevention, such leadership is not impossible. Studies in select developing and industrialized countries reveal the critical roles of consistent, visible political leadership and commitment, along with community mobilization, in slowing the epidemic. For example, in Uganda, a country ravaged by HIV/AIDS, government leaders openly acknowledged the epidemic and took active steps to prevent its spread by creating, in 1986, a National AIDS Control Programme. The program, which involves collaborations among community, government, and donor agencies, includes extensive prevention education campaigns to promote safer sexual behavior, STD prevention and treatment, condom distribution, HIV counseling and testing, and community mobilization to promote behavior change (UNAIDS, 1998; Abdool Karim et al., 1998). These efforts have contributed to high levels of awareness about HIV/ AIDS and declines in HIV incidence among some populations in Uganda (UNAIDS, 2000; UNAIDS, 1998). Political commitment and strong public health programs have also helped Thailand reduce HIV incidence among some of its populations (UNAIDS, 1998; Nelson et al., 1996), and they have helped Senegal maintain one of the lowest HIV incidence rates in Africa (UNAIDS, 1999). Among industrialized countries, government leaders in Australia and the Netherlands have worked with communities to develop policies that minimize the harm incurred by drug abuse and reduce stigmatization of drug users. These countries offer drug abuse treatment on demand; they also have rapidly expanded the availability of methadone maintenance, and they have successfully developed innovative methods for targeting drug users and slowing the HIV/AIDS epidemic among IDUs (Drucker et al., 1998). Perhaps the most impressive aspect of these successes is that, in some cases, such leadership has occurred in countries that have fewer educational, financial, biomedical, and social resources than does the United States.

While there have been prevention successes in the United States as a result of community mobilization, these have generally occurred on a more localized scale and often in the absence of high-level political leadership. For example, community mobilization in the gay community in the early and mid-1980s led to significant changes in sexual behavior and declines in HIV incidence among MSMs in major urban epicenters such as New York and San Francisco (Katz, 1997). These efforts preceded the development of any official public education programs (NRC and IOM, 1993).

UNREALIZED OPPORTUNITIES

The Committee identified four specific instances in which the social and political barriers described above have led to public policies that run counter to the scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions. These instances involve access to drug abuse treatment, access to sterile drug injection equipment, comprehensive sex education and condom availability in schools, and HIV prevention in correctional settings. These examples fall into two categories: (1) those in which policies impede implementation of effective HIV prevention efforts, and (2) those in which policies encourage funding for programs with no evidence of effectiveness. We believe that continuing to support such policies will result in unnecessary new HIV infections, lives lost, and wasted expenditures.

Access to Drug Abuse Treatment and Sterile Injection Equipment

Injection drug use is a major factor in the spread of HIV in the United States, accounting for 22 percent of new AIDS cases in 1999 (CDC, 2000a). Although the primary route of transmission among IDUs is through sharing of contaminated injection equipment, sexual partners and children of IDUs are also at high risk for infection (NRC and IOM, 1995). Non-injection drug use (e.g., use of alcohol, methamphetamines, crack cocaine, inhalants) also increases the likelihood of HIV infection and transmission through increasing high-risk sexual behaviors (IOM, 1997b).

Two of the most effective strategies for preventing HIV infection among IDUs include eliminating or reducing the frequency of drug use and associated risk behaviors through drug abuse treatment, and reducing the frequency of sharing injection equipment through expanded access to sterile injection equipment. However, legal, regulatory, and funding barriers prevent widespread implementation of these interventions.

Access to Drug Abuse Treatment

Drug abuse treatment can be provided in a variety of care settings (e.g., outpatient, residential, inpatient) using two primary types of interventions: pharmacotherapy or psychosocial/behavioral therapy. Pharmacotherapy, such as methadone maintenance treatment for opiate addiction, relies on medication to block the euphoria of the drug and the cravings and withdrawal symptoms associated with drug dependency. Psychosocial/behavioral therapies include skills training or a variety of counseling approaches. Some programs combine elements of the two approaches; for instance, many methadone maintenance programs also utilize some form of counseling or psychotherapy (GAO, 1998).

Studies conducted over three decades have demonstrated the effectiveness of drug abuse treatment in reducing drug use (NIH, 1997a; GAO, 1998; OTA, 1990). Methadone maintenance has been the most rigorously studied treatment modality, and it has been shown to be the most effective approach for treating opiate addiction, particularly when combined with counseling, education, and other psychosocial support services (NIH, 1997b; GAO, 1998).3 Methadone maintenance also has been associated with other positive outcomes such as improved social functioning among those on maintenance and decreased crime rates (GAO, 1998; NIH, 1997b; IOM, 1995b). The recent nationwide Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study concluded that other common forms of drug abuse treatment (long-term residential, outpatient drug free, and short-term inpatient programs), in addition to methadone maintenance, are also effective in reducing drug use and in improving social functioning for a variety of drug-using populations4 (Hubbard et al., 1997). There is less agreement, however, about the most appropriate treatment approach and setting combinations for non-opiate drug abusing populations (GAO, 1998; IOM, 1990).

In recent years, a number of studies have found that drug abuse treatment also reduces risk behaviors associated with HIV/AIDS. Methadone maintenance, which reduces injection and needle-related behaviors that place individuals at risk for HIV have shown particular success (Broome et al., 1999; Magura et al., 1998; Camacho et al., 1996; Longshore et al., 1993; Ball et al., 1988). For example, one study of opiate-addicted IDUs found a six-fold difference in HIV seroconversion rates between those in methadone treatment (seroconversion of 3.5 percent) and addicts who did not enter treatment (seroconversion rate of 22 percent) (Metzger et al., 1993). Drug abuse treatment reduces sex-related risk behaviors (Broome et al., 1999; Magura et al., 1998; Camacho et al., 1996), although this is not a traditional objective of drug treatment (Broome et al., 1999) and earlier findings have been inconsistent (Fisher and Fisher, 1992).

Despite the effectiveness of treatment, many people who could benefit from treatment do not receive it. The Office of National Drug Control Policy estimates that, of the approximately 5 million individuals with

chronic, severe drug problems in the United States in 1998,5 only 2.1 million (43 percent) received treatment (ONDCP, 2000c). During the same year, approximately 20 percent of the estimated 810,000 heroin addicts were in methadone treatment (ONDCP, 2000a).

Many factors contribute to this treatment gap, including insufficient public and private funding to provide treatment on request, restrictive regulations and policies, the unwillingness of some addicted individuals to enter treatment, the difficulty of linking drug users with the appropriate treatment modality (due to incomplete knowledge of best practices), and insufficient knowledge about treatment services being conducted at the state and local level6 (ONDCP, 2000c). The discussion below focuses on the first two factors, insufficient funding to provide treatment on request and restrictive policies and regulations regarding methadone treatment, as these are examples of policies driven by underlying social attitudes regarding drug use.

The limited public and private sector financing is a significant factor affecting the availability of drug abuse treatment services (ONDCP, 2000c), particularly for low income and uninsured individuals. Over time, support for drug abuse treatment has led to a distinctly two-tiered treatment system that is distinguished primarily by mode of financing (IOM, 1990). The publicly supported treatment system serves primarily indigent clients, while the private system serves primarily clients with private health insurance or those who can afford to pay for treatment (IOM, 1990; Weisner et al., 1999). Of the estimated $7.6 billion spent on drug abuse treatment in 1996, public-sector spending accounted for approximately $5 billion (66 percent), while private sources accounted for $2.6 billion (34 percent) (McKusick et al., 1998). Of the public-sector funding, non-insurance sources accounted for nearly half (47 percent) of total drug abuse

treatment spending. These sources included federal block grants (e.g., the SAPT Block Grant), funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Defense, and funding from state and local governments. Public insurance programs, including Medicaid and Medicare, contributed approximately one-fifth (19 percent) of total drug abuse treatment spending (McKusick et al., 1998).

Recent changes in public and private insurance coverage may have affected access to drug abuse treatment. In 1996, Congress passed legislation that eliminated substance abuse as a primary qualifying diagnosis for federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) (Goldstein et al., 2000; Swartz et al., 2000). These changes eliminated cash and Medicaid benefits for approximately 250,000 individuals nationwide (Goldstein et al., 2000).7 According to some observers, this policy change was made largely in response to press reports that federal disability payments were supporting or encouraging drug use (Swartz et al., 2000). Some individuals who were disqualified from SSI or SSDI were able to requalify under another disability category.8 However, this change eliminated the primary source of coverage for substance abuse treatment services for many low income individuals (Horgan and Hodgkin, 1999). Many former SSI recipients who lost benefits as a result of the change, and who continued to be unemployed or underemployed, had high rates of drug dependence and co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Swartz et al., 2000). These factors were major impediments to finding stable employment. One recent study found that only a small proportion of the sample of former SSI drug and alcohol addicted recipients were able to gain even marginal employment one year after termination of benefits (Swartz et al., 2000).

On the private sector side, the scope of benefits for substance abuse treatment is generally limited and less comprehensive than for other illnesses (Horgan and Hodgkin, 1999). While coverage for inpatient detoxification is generally treated like coverage for other inpatient care, coverage for inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient care is generally more restricted (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999, 1998). A recent study found that private insurance coverage for drug abuse treatment has decreased in previous years through the imposition of formal limits, such as restric-

tions on the number of hospital days and outpatient visits, or maximum dollar coverage (McKusick et al., 1998).

Treatment capacity has historically been limited in the public treatment system, particularly in areas with high prevalence of drug abuse. In contrast, the private sector treatment system has reserve capacity in many areas (IOM, 1990). A 1997 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) survey of treatment facilities with residential and inpatient treatment beds suggests similar findings. The survey shows that reserve capacity was lowest in government-owned hospitals and treatment facilities, while reserve capacity was highest among privately-owned treatment facilities (SAMHSA, 1999a).

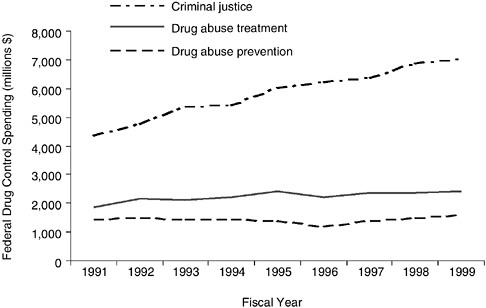

Federal drug control policy over the past 20 years has contributed to the capacity constraints in the public treatment system. The federal government has provided substantial increases in funding to expand the capacity of prisons for drug offenders, but relatively meager increases for drug abuse treatment (Kleiman, 1992). Indeed, an erosion in federal funding for drug abuse treatment between 1976 and 1987 essentially halted growth in the public treatment sector (IOM, 1990). While the public treatment system remained neglected throughout most of the 1980s, federal investments in the criminal justice system experienced a period of unprecedented growth. Although federal funding for drug abuse treatment has increased over the past decade, the growth rate for drug abuse treatment spending remains much flatter than the growth rate for criminal justice spending (ONDCP, 2000b) (see Figure 7.1).9 The ongoing capacity constraints in publicly financed treatment settings, however, suggest the need for significant, continued investment.

Government regulations also limit the availability of treatment for those in need. Methadone, in particular, is subject to extensive regulation.10 At the federal level, methadone is regulated in three ways, making it the nation’s most regulated medication. First, the manufacturing, labeling, and dispensing of methadone are subject to Food and Drug Adminis-

FIGURE 7.1 Federal drug control spending, Fiscal Years 1991–1999. NOTE: Spending reported in 1992 dollars. SOURCE: Nominal drug control expenditure data from the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP, 2000b). Price deflators were provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

tration (FDA) standards regarding safety, efficacy, and quality of all prescription drugs. Second, it is regulated by the Drug Enforcement Agency under the requirements for schedule II narcotics to prevent diversion and illegal use. Third, methadone is subject to a unique set of regulations, established by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), that controls how and under what circumstances methadone may be used to treat opiate addiction. In addition to federal regulations, methadone is often further restricted by many states, and it is sometimes regulated at the county and municipal level (IOM, 1995b).11

These extensive regulations have had several unintended consequences. First, treatment programs are not tailored to individual needs and may provide subtherapeutic doses (Strain et al., 1999; IOM, 1995b; D’Aunno and Vaughn, 1992), thus increasing the likelihood of treatment failure. Second, regulations impose limits on the ability of physicians and

other health care professionals to exercise professional judgment in providing methadone maintenance treatment for their patients (IOM, 1995b). Third, isolation of treatment centers from the mainstream medical care system creates barriers to linkages with other ancillary services (e.g., mental health care, medical care) (IOM, 1995b). Fourth, there are economic costs (shared by programs, insurers, patients, and tax payers) associated with assuring compliance with regulatory requirements (IOM, 1995b). Finally, participation in methadone treatment results in a significant loss of patient autonomy and a climate of social control (Kleiman, 1992). Dependence on methadone makes patients vulnerable to threats of or actual withholding of the medication. Many addicts are unwilling to relinquish this autonomy until they are so desperate that they do not have a choice. Many addicts with jobs or other routine daily activities also find the current regulations requiring them to attend methadone clinic on a daily basis too burdensome (IOM, 1995b).

Although this web of regulations was initially developed, in part, in response to reports of abuses of methadone, its primary goal was to address concerns about its illegal diversion (IOM, 1995b). Evidence indicates, however, that the amount of methadone diverted for illicit use is relatively small (IOM, 1995b). The extensive regulation of methadone places too much emphasis on protecting society from methadone itself, rather than from the addiction, violence, and infectious disease morbidity that methadone maintenance treatment can help prevent (IOM, 1995b). Several expert panels (NIH, 1997b; IOM, 1995b) have consequently recommended that current regulations be modified to give greater weight to clinical judgment and to allow for improved access to methadone treatment.12

Many of the factors limiting access to or availability of drug abuse treatment are related to several common misperceptions. For example, a recent IOM study noted that one of the most enduring myths related to addiction is that treatment for these disorders is ineffective (IOM, 1997a). However, numerous studies establish addiction as a chronic, relapsing medical condition that can be effectively managed through treatment,13

with significant benefits accruing to both the individual and society (NIH, 1997b; NRC and IOM, 1995). Other misconceptions appear to flow from the stigma surrounding drug abuse and addiction (NIH, 1997b; IOM, 1997a; IOM, 1998; Drucker et al., 1998). Public attitudes toward addiction are overwhelmingly negative, with many people believing that addiction is simply a moral failing or a self-induced problem resulting from lack of willpower or motivation (NIH, 1997b; IOM, 1997a; IOM, 1995b).

The stigma surrounding drug use also can isolate drug users from medical and social services, such as education, prevention, or drug abuse treatment efforts, that could help reduce the risk of HIV (Drucker et al., 1998). In addition, stigma may limit public support and advocacy for drug abuse treatment. For instance, the “not in my backyard” syndrome has seriously hindered efforts to site drug abuse treatment facilities in new areas (IOM, 1998). Similarly, unlike other chronic diseases, such as cancer or heart disease, which have strong advocacy organizations and patient constituencies arguing for expansion of prevention, treatment, and research, there are few advocates for the drug addicted population (IOM, 1998).

The underlying misperceptions and stigma associated with addiction, drug use, and treatment have shaped policy decisions and public support of efforts to address the twin epidemics of HIV and substance abuse. Previous federal policy largely focused on increasing funding for imprisonment of drug sellers and users, with relatively small increases for drug abuse treatment (Kleiman, 1992). The national policy to incarcerate drug offenders has been a major contributor to the explosive growth in the incarcerated population over the past decade.

There are indications that the federal response may reflect public sentiment. A recent study reviewing 47 national public opinion polls and surveys conducted between 1978 and 1997 showed strong support for criminal justice responses to the drug problem, but relatively weak support for increasing funding for drug abuse treatment. While most Americans (58 percent) do not see the nation’s illegal drug problem improving despite significant increases in national spending, they continue to support the same general policy direction as followed in the past (Blendon and Young, 1998).

The Committee believes that drug abuse treatment is an effective, but highly underutilized HIV prevention strategy. However, there is increasing support on the federal level for closing the public drug abuse treatment gap (ONDCP, 2000c; ONDCP, 1999). SAMHSA, the federal agency

|

|

disease, which is manifested by a complex set of behaviors resulting from genetic, biological, psychosocial, and environmental interactions (IOM, 1997a). |

charged with improving the quality and availability of substance abuse and mental health prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation services, has a critical role in leading efforts to address the interrelated epidemics of substance abuse, mental illness, and HIV. In addition, collaborations among a multitude of federal, state, and local agencies and private insurers that fund and administer drug abuse treatment programs will be necessary to reduce the treatment gap and change social and cultural norms and beliefs about drug abuse and addiction.

Therefore, the Committee recommends that:

Federal agencies (including the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Health Care Financing Administration, the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse), state and local agencies, and private insurers that fund, administer, or conduct research on drug abuse treatment programs should collaborate to develop mechanisms to: (1) increase drug treatment resources to the level needed for all of those requesting access; and (2) integrate and link these services with appropriate psychiatric and HIV prevention and treatment services.

Access to Sterile Drug Injection Equipment

Drug abuse treatment is not a panacea for the drug epidemic, however. Regardless of the availability of treatment opportunities, a certain portion of drug users will continue to inject drugs. For those who cannot or will not stop injecting drugs, the one-time use of sterile needles and syringes remains the safest and most effective method for preventing HIV transmission. Indeed, a recent study produced similar results, suggesting that expanded provision of needle exchange programs in the United States could have averted between 10,000 and 20,000 new infections over the past decade (Lurie and Drucker, 1997).

Although many communities and law enforcement officials have expressed concern that increasing availability of injection equipment will lead to increased drug use, criminal activity, and discarded contaminated syringes, studies have found no scientifically reliable evidence of these negative effects (GAO, 1993). Studies also have shown that needle exchange programs serve as an important link to other medical and social services, particularly drug abuse treatment and counseling programs (Lurie and Reingold, 1993; Heimer, 1998). A review by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine concluded that needle exchange programs reduced risk behaviors, such as multi-person reuse of

syringes, by 80 percent and led to reductions in HIV transmission of 30 percent or more (NRC and IOM, 1995). A study of a needle exchange program in New Haven, Connecticut, estimated that the program led to a 33 percent reduction in HIV infection rates among drug users, without any increase in the level of substance abuse (Kaplan and O’Keefe, 1993; Kaplan, 1995). Similarly, in 1992, the partial repeal of syringe prescription and drug paraphernalia laws in Connecticut increased IDUs’ access to sterile syringes (Valleroy et al., 1995). Fewer IDUs reported purchasing syringes on the street after the change (74 percent before versus 28 percent after). Among IDUs who reported ever sharing a syringe, syringe sharing also declined after the new laws (52 percent before versus 31 percent after) (Groseclose et al., 1995).

Despite such compelling empirical evidence, however, states and the federal government limit the availability of sterile injection equipment through a series of legal and funding mechanisms (Gostin, 1998). All 50 states have laws that restrict the sale, distribution, and/or possession of injection equipment: 49 states have drug paraphernalia laws that prohibit the manufacture, sale, distribution, possession, or advertisement of any device, including syringes, that may be used in preparing or injecting illicit drugs; and 14 states have syringe prescription laws that require a medical prescription for the sale or possession of injection equipment (Burris et al., 2000). As of 1997, 23 states had pharmacy regulations that limited the ability of pharmacists to dispense injection equipment without verification that its use has a valid medical purpose (Gostin et al., 1997). In addition, the federal Mail Order Drug Paraphernalia Act prohibits sale and transportation of syringes and other drug paraphernalia in interstate commerce (Gostin, 1998).

In addition, a series of statutes enacted by Congress since 1988 specifically prohibit the use of federal funds to support needle exchange programs, regardless of whether or not programs are legally authorized by the individual state. Under the fiscal year 1998 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Appropriation Act (P.L. 105-78), however, the federal funding ban could be lifted if the Secretary of Health and Human Services determined that needle exchange programs were effective in preventing the spread of HIV and did not encourage illicit drug use. Based on findings from a number of expert review panels and federally funded studies, Secretary Donna E. Shalala announced on April 20, 1998, that there was sufficient empirical evidence to meet this two-pronged test (DHHS, 1998). Despite the Secretary’s finding, however, the Administration did not rescind the ban—largely out of political concerns, according to some observers—(Stolberg, 1998) opting instead to allow local communities to implement their own needle exchange programs, using their own resources to fund them (DHHS, 1998).

These legal and funding restrictions limit syringe access in several ways. First, prescription laws and pharmacy regulations limit the ability of pharmacists to dispense syringes over the counter. In addition, drug paraphernalia laws limit the willingness of injection drug users to adopt safer injection practices (e.g., carrying their own injection equipment) out of fear of arrest or prosecution. Finally, syringe prescription laws limit the legal establishment and operation of needle exchange programs, and funding restrictions limit the financial capability of these programs to operate. Although the number of reported needle exchange programs has increased over the past several years (CDC, 1998), these restrictions still severely restrict the number of these programs. As of May 2000, an estimated 156 needle exchange programs were in operation in the United States (NASEN, personal communication).

The Committee believes that improving access to sterile injection equipment is a critical component of HIV prevention. Therefore, the Committee recommends that:

Legal barriers to the purchase and possession of injection equipment should be removed, including repeal of state prescription laws and modification of state and local drug paraphernalia laws. In addition, the Administration should rescind the existing prohibition against the use of federal funds for needle exchange to allow communities that desire such programs to institute them using federal resources.

Comprehensive Sex Education and Condom Availability in Schools

Teenagers and young adults are at increasing risk for acquiring HIV. In 1998, AIDS was the ninth leading cause of death among youth ages 15–24, and the fifth leading cause of death among individuals 25–44, many of whom were infected as teenagers (Murphy, 2000). The majority of infections among adolescents and young adults are sexually transmitted (CDC, 2000a). Adolescents are at higher risk for acquiring HIV than adults for several reasons: they are more likely to have multiple (either sequential or concurrent) sexual partners, they are more likely to engage in unprotected sex, and they are more likely to select partners at higher risk (CDC, 1999c). These high-risk behaviors also place youth at increased risk for other STDs and for unintended pregnancy. Indeed, the United States has the highest teenage pregnancy rate of all developed countries (CDC, 2000b), and over 3 million teenagers acquire an STD in any given year (IOM, 1997b). In light of these facts, youth constitute an extremely important population for HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention efforts.

The school setting is an obvious venue for providing such informa-

tion, given that nearly 95 percent of all youth ages 5–17 years are enrolled in primary and secondary schools (Department of Education, 2000). To a large extent, policies regarding sex education and condom availability in schools are determined by state mandates and by policies established within local school districts. As a result, the specific content of sex education and condom availability programs varies substantially across school districts. In general, sex education curricula fall into two broad categories: those that teach an abstinence-only message, and those with a comprehensive message. Abstinence-only programs teach abstinence outside of marriage as the only option, with discussions of contraception either entirely prohibited or limited to its shortcomings. In contrast, comprehensive sex education programs provide information about abstinence in the context of a broader sexuality education program, and they also may make condoms available to students. Also included under the rubric of programs with a comprehensive sexual health and education message are “abstinence-plus” programs that teach abstinence as the preferred option for adolescents, but also permit discussion of contraception, pregnancy, and disease prevention (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999b).

Decisions regarding the content of sex education curricula and whether or not to make condoms available at schools have been the focus of considerable debate and controversy. Proponents of abstinence-only policies argue that providing information about contraception or providing condoms to adolescents sends a mixed message to youth and may promote sexual activity (e.g., accelerating the onset of sexual intercourse and increasing the frequency of sexual intercourse or number of sexual partners) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999b). Proponents of comprehensive programs argue that while abstinence should be encouraged until youth are emotionally and physically ready for sex, it is crucial to provide youth who may be sexually active with information and contraceptive methods that can protect them from STDs and unintended pregnancy (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999b).

Studies reviewing the scientific literature, as well as expert panels that have studied this issue, have concluded that comprehensive sex and HIV/AIDS education programs14 and condom availability programs can be effective in reducing high-risk sexual behaviors among adolescents

(Kirby, 2000; IOM, 1997b; IOM, 1995a; Kirby, 1995). In addition, these reviews and expert panels conclude that school-based sex education and condom availability programs do not increase sexual activity among adolescents.

National surveys show strong public support for comprehensive sex education policies and condom availability programs. A 1998 poll found that 81 percent of adults supported schools teaching information about abstinence as well as about contraception and prevention of STDs (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1998). A 1991 poll showed that 64 percent of adults favored making condoms available in high schools (Roper Organization, 1991), and a 1999 poll found that 53 percent of adults thought school personnel should make condoms available to sexually active youth (Haffner and Wagoner, 1999). Condom availability programs are also endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 1995).

In contrast, two recent reviews of the literature on abstinence-only education programs concluded that the evidence was insufficient to determine whether abstinence programs decrease sexual activity (Kirby, 2000; Maynard, 2000). One of these reviews concluded that the weight of the evidence indicated that abstinence programs do not delay the onset of intercourse, but significant methodological limitations could have obscured the impact of these interventions (Kirby, 2000). Public support for abstinence-only education programs is also limited. In a 1998 poll, only 18 percent of adults thought abstinence should be the only topic of discussion (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1998).

Still, many school districts do not provide comprehensive programs. A 1998 national survey found that of school districts with a policy to teach sex education, only two-thirds permitted positive discussions of contraception (Landry et al., 1999). In addition, a 1995 survey found that only 2.2 percent of all public high schools and 0.3 percent of school districts made condoms available to students (Kirby and Brown, 1996).

In contrast, abstinence-only programs have proliferated. A 1998 survey found that one-third of all school districts with a policy to teach sex education used abstinence-only education that prohibited dissemination of any positive information about contraception (Landry et al., 1999). This study found that every region of the country had a significant proportion of districts with abstinence-only policies; however, districts in the South were five times as likely as those in the Northeast to have an abstinence-only policy. The survey also found that among those districts that changed their sex education policies, twice as many adopted a more abstinence-focused policy than vice versa (Landry et al., 1999).

While federal involvement in sex education has historically been limited, two federal programs provide sizeable amounts of funding for abstinence-only sex education programs: the 1981 Adolescent Family Life Act

(AFLA) and the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) (42 U.S.C.A. §§ 601 et seq.). The AFLA, which provides funds for abstinence-only sex education under Title XX of the Public Health Service Act, was enacted by Congress with the primary goal of preventing teenage pregnancy by promoting abstinence education, providing care for pregnant and parenting teens, and conducting research on teen sexuality. Since 1982, an estimated $60 million has been spent on some form of abstinence education through AFLA, although no exact figures are available (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999c). The PRWORA, which was part of the 1996 welfare reform law, provides states with a total of $50 million annually for five years, from FY1998 through FY2002, to support abstinence-unless-married education programs.15 States that accept federal funding are required to provide 75 percent in matching funds, resulting in a total of as much as $87.5 million per year ($437.5 million over five years) for abstinence-only programs. By FY99, all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands had applied for and received funding under PRWORA for abstinence-only education. Recent reviews show that states use their funds for a wide array of programs, including school- and community-based programs (SIECUS, 1999). A national evaluation of this initiative is currently being conducted using funds allocated as a part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, and many states are undertaking separate evaluations of their programs (AMCHP, 1999).

The Committee believes that investing hundreds of millions of dollars of federal and state funds over five years in abstinence-only programs with no evidence of effectiveness constitutes poor fiscal and public health policy. The Committee concurs with the prior conclusion of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Panel on Interventions to Prevent HIV Risk Behaviors (NIH, 1997b): that legislative restrictions discouraging ef-

fective programs aimed at youth must be eliminated, and that programs must include information about safer sex behaviors, including condom use.

Therefore, the Committee recommends that:

Congress, as well as other federal, state, and local policymakers, eliminate requirements that public funds be used for abstinence-only education, and that states and local school districts implement and continue to support age-appropriate comprehensive sex education and condom availability programs in schools.

HIV Prevention in Correctional Settings

Approximately 6.3 million adults were under the supervision of federal, state, and local correctional authorities in 1999 in the United States. An estimated 1.9 million of these individuals were incarcerated in prisons and jails (Beck, 2000), and approximately 4.4 million of them were on probation or parole (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2000). Most inmates come from low-income urban areas, and minorities are disproportionately represented among inmates. Many inmates have a history of substance use or sexual behaviors that place them at high risk for HIV infection, (Hammett et al., 1998; Braithewaite et al., 1996), as well as for STDs, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and other health problems (Hammett et al., 1998; Dean-Gaitor and Fleming, 1999). A recent survey estimated that in 1997, AIDS prevalence was five times higher, and HIV prevalence was eight to ten times higher, in prisons and jails than in the general population16 (Hammett et al., 1999). As a result, the correctional system constitutes a critical setting for HIV prevention and treatment interventions. The benefits of such efforts will extend beyond the correctional system as well, since the circulation of infected or high risk individuals between correctional facilities and communities is a dynamic that now helps maintain the epidemic and contributes to new cases each year in many urban areas (Braithewaite et al., 1996).

The primary barrier to implementing HIV prevention programs and strategies in correctional settings is the difference in priorities between public health officials and correctional system officials. The public health community’s primary focus is to improve the health of inmates and to protect the community to which they return from the spread of infection.

Thus, public health officials tend to advocate strategies that, by default, acknowledge the occurrence of sexual activities and drug use in correctional settings. Conversely, the primary focus of correctional officers is to ensure a controlled and secure environment. To do so, they must uphold the policies and regulations of the correctional system that expressly forbids those same activities.

Implementing acceptable HIV prevention strategies in the correctional system will require extensive collaborations among correctional systems, public health officials, and community-based organizations, and developing these collaborations will require significant effort and cooperation by all parties involved. However, failure to address HIV prevention needs in prisons and jails is a shortsighted strategy that will lead to unnecessary new infections and wasted expenditures. There are four primary routes for addressing this issue: helping inmates when they are released, providing HIV/AIDS education to inmates, providing drug abuse treatment in correctional settings, and implementing harm reduction programs.

Discharge Planning

Many inmates, particularly those with a history of substance abuse, have difficulty successfully transitioning from correctional settings to the community. The transition can be especially difficult for inmates with HIV/AIDS, given their increased needs for health care and support services. Discharge planning is critical for these populations, as it facilitates linkages with appropriate public health and community-based resources for follow-up care, treatment, and support services (Hammett et al., 1998).

Although most correctional systems report some type of discharge planning for HIV-infected inmates, only three-fourths of federal and state systems actually make referrals and less than one-third arrange follow-up appointments for inmates for HIV medications, HIV counseling, Medicaid and related benefits, and other types of services or support (Hammett et al., 1999) (see Table 7.1). Several other barriers hinder the smooth transition of inmates into the community. Many inmates are incarcerated in correctional facilities far from their homes, thus making it more difficult to facilitate linkages to community services in their cities of residence (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1998). Existing community programs may lack the capacity to provide the necessary prevention, care, and support services to new clients; additionally, waiting lists, limited placements, and increasing demands for certain types of services (e.g., substance abuse treatment) bring unwanted delays to those in need. Other factors—such as staffing constraints, lack of cooperation between the criminal justice system and community organizations, difficulty in maintaining accurate records, and communication difficulties—are also

TABLE 7.1 HIV/AIDS Education, Harm Reduction, and Discharge Planning Programs in U.S. Adult Correctional Systems, 1997

|

|

State/Federal Prison Systems (N = 51) |

City/County Jail Systems (N = 41) |

||

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

Type of HIV Education Programs |

||||

|

Instructor-Led Education |

|

94 |

|

73 |

|

“Comprehensive” HIV/AIDS education programs* |

|

10 |

|

5 |

|

Topics Covered in HIV Education Programs |

||||

|

Basic HIV information |

51 |

100 |

35 |

85 |

|

Meaning of HIV test results |

51 |

100 |

38 |

93 |

|

Negotiation skills for safer sex |

21 |

41 |

19 |

46 |

|

Safer injection practices |

23 |

45 |

20 |

49 |

|

Tattooing risks |

42 |

82 |

22 |

54 |

|

Alcohol/drug risks |

41 |

80 |

30 |

73 |

|

Self-perception of risk |

30 |

59 |

27 |

66 |

|

Identifying barriers to behavioral change |

28 |

55 |

23 |

56 |

|

Harm Reduction Strategies |

||||

|

Make condoms available |

2 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

|

Make bleach available (for any purpose) |

10 |

20 |

8 |

20 |

|

Make needles/syringe equipment available |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

impediments to effective transitions between correctional systems and the community (HRSA, 1995).

Several correctional facilities, however, have developed promising models for improving discharge planning and continuity of care for inmates upon their return to the community. Seven programs, jointly funded by the CDC and Ryan White CARE Act’s Special Projects of National Significance in fiscal year 1999 and fiscal year 2000, provided comprehensive HIV education and transitional services for inmates. Evaluations of these programs have identified six key elements of success: case management, staff skills and training, intra- and interagency referral, client participation in discharge planning, use of former inmates as service providers, and recognition of HIV as a problem by correctional facilities and community agencies (HRSA, 1995).

One model program, funded by the CDC and HRSA, for example, was developed by the Hampden County Correctional Center in Massachusetts. This comprehensive HIV program includes case management and discharge planning components to link infected inmates with health care services upon their release. Releasees are also linked into agencies that can assist them with other concerns, such as housing and employment. This program has shown initial signs of success: in 1997, more than 70 percent of persons with HIV/AIDS who had been released kept their appointments (NIJ et al., 1999).

HIV Prevention Education

While all state and federal prison systems offer basic HIV information and instruction on the meaning of an HIV test result, only two-thirds of the systems provide information on safer sex practices, and less than half teach safer sex negotiation skills or provide information about safer drug injection practices (see Table 7.1). Only 10 percent of prisons and 5 percent of jails currently offer comprehensive programs of instructor- and peer-led education, pre- and posttest counseling, and multisession prevention counseling (Hammett et al., 1999).

This failure to provide adequate education stems from the hesitancy of correctional facility administrators to acknowledge or accept that high-risk behaviors occur within the correctional system. Because sexual activity and injection drug use are illegal in prisons and jails, many seem to believe that teaching preventive behaviors will be viewed as condoning illegal practices (Braithewaite et al., 1996). Even if inmates are not engaging in risk behaviors while incarcerated, instruction in safer sexual and drug use behavior would be beneficial for when they are released into their communities.

Drug Abuse Treatment

There is a high prevalence of substance abuse problems among incarcerated populations. A 1997 survey found that more than 80 percent of state prisoners and more than 70 percent of federal prisoners reported past drug use, more than 40 percent of federal prisoners reported using drugs in the month prior to their offense, and one-quarter of state prisoners and one-sixth of federal prisoners indicated past alcohol or substance abuse or dependence. Further, one in six state and federal prisoners reported the need for drug money as the reason for the crime that led to his or her incarceration, and one-third of state prisoners and one-fifth of federal prisoners reported using drugs at the time of their offense (Mumola, 1999). Many substance-using criminal offenders under the control of the criminal justice system are not incarcerated, but are on parole, probation, or other supervised arrangements in the general community. Many of these individuals are poorly supervised, lack employment or health insurance coverage, and often relapse into substance use or other risk behaviors (Pollack et al., 1999).17

However it has been estimated that only 18 to 25 percent of inmates in need of treatment are actually receiving it (Mumola, 1999; National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1998). A recent study of women’s prisons also found long waiting lists for residential drug abuse treatment programs (GAO, 1999). In a 1997 survey, federal correctional facilities were the most likely to provide drug treatment (94 percent), followed by approximately 56 percent of state facilities, and 33 percent of local facilities. Approximately 173,000 inmates received substance abuse treatment, with 70 percent receiving treatment or counseling in the general facility population, 28 percent receiving treatment in specialized substance abuse treatment facilities within the institution, and 2 percent receiving treatment in an inpatient hospital/psychiatric setting (SAMHSA, 1999b).18

In a 1996 survey conducted by the Federal Bureau of Justice and correctional systems in 47 states and Washington, D.C., 75 percent of systems cited budgetary constraints as the main reason why they did not offer drug treatment (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1998). Another study identified additional barriers, including a limited number of substance abuse counselors, frequent movement of inmates, general correctional problems, problems with aftercare provision, and

legislative mandates (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1998). This study also found that prisoners with substance abuse problems may be reluctant to participate in drug treatment programs. Their reluctance was attributed to other aspects of correctional life (e.g., increased sentences if they admit drug abuse problems, few incentives for early release or parole, and lack of rehabilitative programs) that contributed to feelings of despair and loss of personal empowerment. Thus, it is important to address the multiple needs that substance abusers may have if treatment is to be accepted and effective.

Not all correctional facilities can realistically offer drug treatment services to inmates. For instance, juvenile detention centers and local jails may hold offenders for only a few days. State and federal prisons, which house inmates with longer sentences, have a greater responsibility and capacity to offer substance abuse treatment to their inmates.

Harm Reduction Programs

Harm reduction strategies, including making condoms, needles or syringes, or bleach which can be used to clean needles and syringes,19 available to inmates, have not been widely adopted in U.S. correctional facilities (see Table 7.1). This lack is due to two major factors. First, needles and bleach constitute a serious safety concern in correctional settings, and condoms can be used for smuggling drugs or contraband. The second factor is the apparent belief among most correctional officials that implementing measures targeted at these behaviors would essentially condone them (Hammett et al., 1998). The existence of antisodomy statutes may pose an additional barrier to the implementation of condom availability programs in some states.

According to a 1997 national survey conducted for the National Institute of Justice and the CDC, two state correctional systems (Vermont and Mississippi) and four municipal jail systems (New York City, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco) have provided condoms to their inmates. In addition, the six state or federal prison systems that permitted conjugal visits (as of 1997) also made condoms available to inmates participating in these visits (NIJ et al., 1999). In contrast, condoms are available in most European and Canadian prisons, and condom distribution pilot programs have been initiated in Australia (NIJ et al., 1999).

Correctional facilities with condom distribution programs have re-

ported relatively few problems with use of condoms as weapons or for smuggling contraband (NIJ et al., 1999). In the 1997 survey of facilities, an official at the Mississippi State Prison in Parchman cited only one incident when a condom was used for smuggling (NIJ et al., 1999). In Vermont, officials report that after an initial period of controversy, condom distribution became routine and was no longer an issue. Vermont officials report few problems with the misuse of condoms, and they have observed no evidence that condom distribution has led to an increase in sexual activity or undesirable behavior (NIJ et al., 1999; Braithewaite et al., 1996). In a survey of over 400 correctional officers in Canada’s federal prison system, 82 percent reported that condom availability had created no problems in their facilities (NIJ et al., 1999).

While some U.S. correctional facilities provide information about safer drug injection practices, no facilities distribute needles or injection equipment (Hammett et al., 1999; NIJ et al., 1999). Indeed, possession of needles and syringes is illegal in correctional settings (NIJ et al., 1999). Needle exchange programs have, however, been implemented in prison systems in other countries, with considerable success. Switzerland was the first country to introduce prison needle exchange programs, beginning in 1992. Evaluation of such a needle exchange program in the Hindelbank women’s facility found that the program did not increase drug consumption and significantly reduced the frequency of needle sharing. In addition, there were no reports of needles being used as weapons, and there were no new cases of HIV or hepatitis B reported among program participants. Based on the experience in Swiss facilities, needle exchange programs have been initiated in several prisons in Germany and in at least one prison in Spain. Plans to initiate a pilot needle exchange program in Australia have also been made (NIJ et al., 1999).

Availability of bleach for cleaning injection equipment is also limited in U.S. prisons. Only one facility (San Francisco) has reported making bleach available expressly for cleaning injection equipment (NIJ and CDC, 1995). However, ten state or federal and eight city or county correctional systems report making bleach available to inmates for general purposes (Hammett et al., 1999; NIJ et al., 1999). Bleach is made more widely available in prisons in other countries. Over half of 20 European systems that responded to the 1997 NIJ/CDC survey reported having such policies. A successful pilot study of a bleach kit distribution program in Canada led to the expansion of this program in all Canadian federal facilities (NIJ et al., 1999).

Therefore, the Committee recommends that:

The Department of Health and Human Services should collaborate with the Department of Justice to develop guidelines

to remove policy barriers that hinder the implementation of effective HIV prevention efforts in correctional settings. At a minimum, these guidelines should ensure that:

-

discharge planning is enhanced so that individuals with HIV or who are at high risk for HIV (e.g., due to substance abuse or mental health issues) are linked with appropriate community-based prevention and treatment services;

-

comprehensive HIV prevention education programs for incarcerated individuals and staff are implemented in all correctional settings; and

-

drug treatment is available for inmates with drug abuse problems.

While there is not yet definitive evidence that condom distribution in correctional facilities would reduce HIV transmission, in light of the absence of problems reported by facilities that have implemented such programs, the Committee recommends that condoms be made readily available to incarcerated individuals.

The Committee recognizes that data on HIV sexual transmission in correctional facilities are lacking, as is evidence that condom availability reduces the incidence of sexually transmitted HIV in these settings. Nonetheless, the Committee concludes that providing condoms to inmates is prudent public health practice for the following reasons. First, condoms are clearly the best available means to reduce the risk of sexually transmitting or acquiring HIV among at-risk individuals having intercourse (Davis and Weller, 1999; Pinkerton and Abramson, 1997). Second, studies have documented higher rates of HIV/AIDS among inmates than in the general population (Hammett et al., 1999). Third, the risk of sexual transmission of HIV in correctional facilities is possible because there is evidence (cited in Braithwaite et al., 1996) indicating that sexual activity does occur in correctional settings despite prohibitions against these activities. Finally, correctional facilities in the United States and other countries that have implemented condom distribution programs have reported relatively few logistical or security problems as a result of such programs (NIJ et al., 1999). The Committee further reasons that providing condoms is a very inexpensive intervention. Based on this evidence, the Committee concludes that in the absence of this intervention, inmates are at increased risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV.

The Committee is not making a recommendation at this time with regard to needle availability in correctional settings. The Committee rec-

ognizes that lack of access to sterile injection equipment and/or bleach in correctional facilities may result in fewer averted infections, but we understand the concerns of the correctional system with regard to safety threats (both to corrections staff and other inmates) that could result from making these items available to inmates. However, in the absence of these measures, the Committee believes that HIV educational programs in correctional facilities should include information about safe injection practices and all inmates needing substance abuse treatment should receive such services upon request.

REFERENCES

Abdool Karim Q, Tarantola D, As Sy E, Moodie R. 1998. Government responses to HIV/ AIDS in Africa: what have we learnt? AIDS 11(Suppl B):S143–S149.

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 1995. Condom availability for youth [Web Page]. Located at: www.aap.org/policy/00654.html.

Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP). 1999. Abstinence Education in the States—Implementation of the 1996 Abstinence Education Law. Washington, DC: AMCHP.

Association of Reproductive Health, Association of Nurse Practitioners in Reproductive Health (ARHP and ANPRH). 1995. STD counseling and practices and needs survey. Silver Spring, MD: Schulman, Roca, and Bucuvalas, Inc.

Ball JC, Lange WR, Myers CP, Friedman SR. 1988. Reducing the risk of AIDS through methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29(3):214–226.

Bayne–Smith M. (Ed.). 1996. Race, Gender, and Health. Sage Series on Race and Ethnic Relations, Vol. 15. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Beck A. 2000. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 1999. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Blendon RJ and Young JT. 1998. The public and the war on illicit drugs. Journal of the American Medical Association 279(11):827–832.

Braithewaite RL, Hammett TM, Mayberry RM. 1996. Prisons and AIDS: A Public Health Challenge. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

Broome KM, Joe GW, Simpson DD. 1999. HIV risk reduction in outpatient drug abuse treatment: Individual and geographic differences. AIDS Education and Prevention 11(4):293–306.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2000. U.S. correctional population reaches 6.3 million men and women represents 3.1 percent of the adults U.S. population (Press release). Washington, DC.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1999. Employee Benefits in Medium and Large Private Establishments, 1997, Bulletin 2517. Washington, DC.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1998. Employee Benefits in Medium and Large Private Establishments, 1995, Bulletin 2496. Washington, DC.

Burris S, Lurie P, Abrahamson D, Rich JD. 2000. Physician prescribing of sterile injection equipment to prevent HIV infection: time for action. Annals of Internal Medicine 133(3):218–226.

Camacho LM, Bartholomew NG, Joe GW, Cloud MA, Simpson DD. 1996. Gender, cocaine and during-treatment HIV risk reduction among injection opioid users in methadone maintenance. Drug and Alcohol Dependency 41(1):1–7.

Campbell CA. 1995. Male gender roles and sexuality: Implications for women’s AIDS risk and prevention. Social Science and Medicine 41(2):197–210.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000a. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 1999. 11(2). Atlanta: CDC.