Fast Track: Is It Speeding Commercialization of the Department of Defense Small Business Innovation Research Projects?

Peter Cahill

BRTRC, Inc.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Objective

This paper compares the commercialization potential and performance outcomes to date of research funded by the Department of Defense (DoD) Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program under standard program procedures and under Fast Track. It describes the operation of the SBIR program within DoD and discusses prior studies of SBIR commercialization. It further describes the methodology for establishing study and control group samples for the case studies and for surveys of both the contractors and government technical monitors of SBIR projects.

Methodology

A total of 379 projects were selected from among those that received Phase II awards during 1992–1996 for surveys of contractors and government technical monitors. The contractor questionnaire was derived from the one that the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) used in the 1991 seminal study of SBIR commercialization. The sample consisted of all 48 Fast Track winners in 1996, a control group representative of the 1996 DoD SBIR population (61 projects), 127 Ballistic Missile Defense Office (BMDO) co-investment projects awarded from 1992 to 1996, and a BMDO control group representative of the 1992–1996 DoD SBIR population (143 projects).

Results

Key findings of the contractor survey (70 percent responding) were:

-

Sixty-one percent of Fast Track winners (compared to 32 percent of all other winners) had no prior Phase II awards.

-

At time of application, Fast Track firms were, on average, five years younger (median founding year 1994) and smaller in annual revenue than firms in the other groups.

-

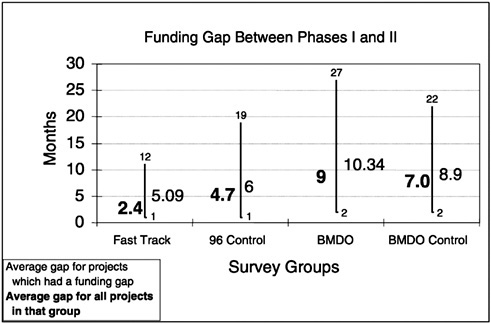

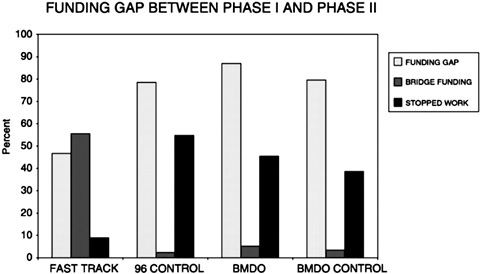

The Fast Track funding gap between Phase I and Phase II was half that of control group. Five times as many control group projects had to stop work because of the gap.

-

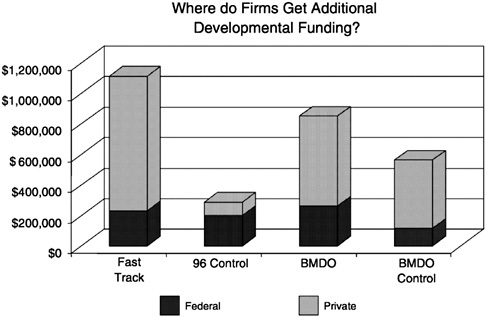

The average additional developmental funding received by Fast Track projects ($1,193,000) is almost five times that of the control group and double that of the more mature BMDO Co-investment and BMDO Control projects. Twenty percent of Fast Track firms have received venture capital compared to 3 percent of all SBIR firms.

-

Although only 14 percent of Fast Track projects have completed Phase II, their average sales are already over $100,000.

-

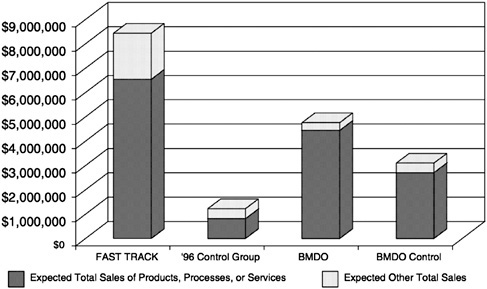

At $8,950,000, the average sales that Fast Track projects expect to achieve by the end of 2001 is over six times greater than expected by the 96 Control group and more than double that expected by the other two groups.

-

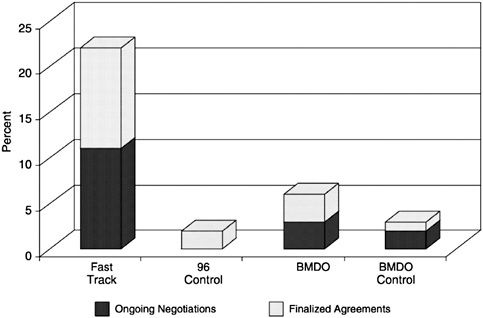

Five times as many Fast Track firms have sold or are negotiating sale of partial ownership. (Such sales, probably linked to obtaining third-party funding, are viewed negatively by some SBIR participants and positively by others.)

Conclusions

Whether it is the validation by a third party to the commercial potential, the timing and magnitude of the additional funding, or merely the reduction in funding gap that contributes most to Fast Track, the program is working. By each primary measurement of commercialization success used in past SBIR studies (sales, additional developmental funding, and expected sales), Fast Track projects are clearly outperforming those in the control group.

INTRODUCTION

This paper documents a portion of the overall National Research Council evaluation of the Department of Defense (DoD) Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program and the Fast Track Initiative. It describes the operation of the SBIR program within DoD and discusses prior studies of SBIR commercialization. It further discusses the survey effort used to examine the program and the sampling methodology used to target the surveys of contractors. The samples used for the contractor survey provided the basis for the survey of government technical monitors of SBIR projects and the case studies, which were conducted by other members of the research team. The contractor surveys indicate that Fast Track is working. It is selecting projects that should succeed in commercialization and it is apparently contributing to their success.

SBIR PROGRAM WITHIN DoD

Background

Congress established the SBIR Program in 1982 to strengthen the research and development (R&D) role of small innovative companies. Ten federal agencies participate in the program in proportion to the size of their external R&D budget. As the agency with the largest R&D budget, DoD provides over half of the total federal SBIR funding. SBIR has become the primary vehicle through which DoD funds R&D projects at small technology companies. With funding of over a half billion dollars in 1998, the program offers DoD a unique opportunity to harness the talents of small technology companies —which studies show to be a potent source of innovation—for the benefit of DoD and the U.S. economy.

SBIR legislation describes three phases for SBIR projects. Phases I and II, funded by the SBIR Program, develop the innovative idea. Phase III involves follow-on non-SBIR government contracts for government application or use of nonfederal funds for commercial application of a technology. Commercial sales are a principal focus of Phase III.

Goals and Administration

The program is authorized by the Small Business Innovation Research Program Reauthorization Act of 1992. In the accompanying House Report, Congress noted that programs that effectively stimulate innovation and accelerate technological advance were key to national economic growth. The report stressed the concentration of scientific and technical talent in small companies and the ability of small businesses to transform R&D results into new products. The legislation addressed the congressional concern that although small businesses were the most productive source of significant innovation in the nation, their share of federally funded R&D was not commensurate with their abilities.

In authorizing the SBIR program, Congress designated four major goals:

-

to stimulate technological innovation,

-

to use small business to meet federal R&D needs,

-

to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation,

-

to increase private-sector commercialization of innovations derived from federal R&D.

In addition to establishing goals, the legislation determined agency participation and funding for the program. Agencies spending more than $100 million annually for external R&D were required to set aside a percentage of their total R&D funds for SBIR. This proportion has grown from 1.25 percent during 1987-1992 to 1.5 percent in 1993 and 1994 to 2.0 percent in 1995 and 1996. Since 1997, not less than 2.5 percent of external R&D funds have been set aside for SBIR.

Each agency with an SBIR program is unilaterally responsible for targeting research areas and administering its own SBIR funding agreements. SBIR funding agreements include any contract, grant, or cooperative agreement entered into between a federal agency and any small business for the performance of experimental, developmental, or research work funded in whole or in part by the federal government.

As indicated in the preceding section, DoD is by far the largest of the federal agencies participating in SBIR. The Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization in the Office of the Secretary of Defense coordinates these efforts, providing oversight and setting policy in coordination with the Director of Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E).

DoD decentralizes most of the administration of the SBIR program to the three Services, four agencies, and one staff element with R&D budgets meeting the legislated requirements: Army, Navy, Air Force, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Ballistic Missile Defense Office (BMDO), the Defense Special Weapons Agency (DSWA), the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), and DDR&E.

The Air Force SBIR program is larger than all of the SBIR programs at the other nine federal agencies, and the Army, Navy, DARPA, and BMDO programs each exceed the size of the programs at seven of the nine other federal agencies. Thus, how well DoD meets the goals of the SBIR program has a major impact on how well the overall program meets its goals.

The legislation requires agencies to issue a solicitation that sets the SBIR process in motion. The solicitation, a formal document issued by each agency, lists and describes the topics to be addressed and invites small businesses to submit proposals for consideration.

Twice a year, DoD issues a combined research solicitation for its eight component programs, indicating each program's R&D needs and interests and invit-

ing R&D proposals from small companies. Companies apply first for a six-month Phase I award of up to $100,000 to test the scientific, technical, and commercial merit and feasibility of a particular concept. If Phase I proves successful, the company may be invited to apply for a two-year Phase II award of up to $750,000 to further develop the concept, usually to the prototype stage. Proposals are judged competitively on the basis of scientific, technical, and commercial merit. Following completion of Phase II, small companies are expected to obtain Phase III funding from the private-sector or non-SBIR military customers to develop the concept into a product for sale in military and/or private-sector markets.

The law requires the Small Business Administration (SBA) to issue policy directives for the general conduct of the SBIR programs within the federal government. These policy directives include elements such as simplified, standardized, and timely SBIR solicitations; a simplified, standardized funding process; and minimization of the regulatory burden for small businesses participating in the program. The most recent policy directive was issued in January 1993. Federal agencies are required to report key data to SBA, which in turn publishes annual reports on the progress of the program.

According to SBA’s SBIR program policy directive, to be eligible for an SBIR award, a small business must be

-

independently owned and operated,

-

other than the dominant firms in the field in which it is proposing to carry out SBIR projects,

-

organized and operated for profit,

-

the employer of 500 or fewer employees (including employees of subsidiaries and affiliates),

-

the primary source of employment for the project’s principal investigator at the time of award and during the period when the research is conducted, and

-

at least 51 percent owned by U.S. citizens or lawfully admitted permanent resident aliens.

Program Administration Within DoD

Commercialization success depends on many factors, some of which are influenced by the agency that makes the SBIR award. Does the topic describe a general need, or a very specific problem? The specificity of the topic may limit proposals and innovative approaches, which may reduce the private-sector appeal of proposals in response to a very specific DoD topic. On the other hand, such specificity may indicate a well-understood need that will result in DoD procurement of the solution to that need. Broad topics give more latitude for a firm to propose something with private-sector appeal; however, the agency may not select the proposal if it sees no clear payoff to DoD. How are topics selected? How

are proposals evaluated—decentralized or centralized, rolling evaluation as received or batched evaluation, first solicitation of the Fiscal Year, second solicitation, or both? Are the procurement officials of the agency involved with topic selection? How rapidly are contracts let? Is bridge funding available between phases? Does the agency fund projects that exceed the Phase II funding limit? Is the agency using SBIR to supplement other research? How often does the agency provide follow-on Phase III R&D funding? What prior relationship has existed between the SBIR firm and the agency or command/laboratory within the agency? All of these factors, which may affect commercialization, vary within and among DoD agencies as described herein.

As indicated earlier, the program administration of SBIR is decentralized in DoD. The reason for this decentralization is that SBIR is part of R&D and, in DoD, R&D is decentralized because each of the agencies conducting R &D has a different mission, structure, and R&D focus. Two of the three Services have had 200 years and the third has had 50 years to evolve its structures in response to changing missions. Although each has the mission to recruit, train, organize, and equip forces for deployment under joint commanders, the differences in equipment needs between Army Divisions, Navy Carrier Groups, and Air Force Wings are dramatic. These differences lead to differences in the kinds of topics, and in the way that the Services have structured their own acquisition organizations and the research, development, and engineering organizations that support them. Certain needs common to all Services have been made the responsibility of a single Service, whose needs and capabilities were predominant. For example, among the Army’s lead service, R&D responsibilities are small arms, food, clothing, and wheeled vehicles. Each Service has R&D organizations at various locations supported by contracting offices. In their areas of interest, Services conduct basic and advanced research, develop and demonstrate technology, and develop and engineer systems. Most of this effort is accomplished through universities and defense contractors. The Services also must provide support in maintaining and upgrading equipment that is already in the field.

DARPA focuses on high-risk, high-payoff critical defense technologies that may support any of the Services or other DoD needs. Most of its focus is on technology development and demonstration. It makes use of Service R&D organizations and contracting agencies to evaluate and support its efforts, which are largely contracted. Much of the DARPA organization is transient. The Services provide people to work at DARPA as program managers for two to three years (less than the life cycle of SBIR from topic generation to completion of Phase II). DARPA gauges success of an R&D project (including SBIR projects) on whether, at the end of the project, the technology is transitioned into one of the Services.

BMDO has the mission its name implies. Much of its R&D is supported out of Huntsville, Alabama, home of one of the Army ’s principal Research, Development, and Engineering Centers. The large expenditure in technology development over the past two decades and the national debate over the affordability and

efficacy of fielding a missile defense system in the near future is indicative that BMDO is pushing the state of the art in many technologies. A larger, more structured and focused organization than DARPA, BMDO also uses the Services to help execute its R&D mission. Neither DARPA nor BMDO has responsibilities for system acquisition or support and upgrade of systems in the field.

DSWA focuses its R&D on the effects of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons (the latter two for defense against such weapons). It does not actually develop or procure weapons, thus limiting the potential for SBIR Phase III funding for their topics. Private-sector sale of SBIR Phase II results tends to be limited to occasional spinoffs of the actual technology in the SBIR. The U.S. Special Operations Command has a small R&D program focused on near-term needs of Special Operating Forces provided by the Services. The Office of the Secretary of Defense DDR&E has a small SBIR program, which has attempted to establish topics with a high potential for dual use.

The SBIR process within a Service must operate within the organization and research, development, and acquisition (RDA) processes used by that Service. In decentralized systems such as those employed by the Navy, SBIR procedures vary among the systems commands. In general, SBIR is integrated into the R&D programs of each systems command. In the Navy, the Acquisition Program Executive Officers play a significant role in topic generation and selection of proposals, especially for Phase II. Acquisition Program Offices frequently fund Phase III or provide additional Phase II funding. The usefulness of the SBIR results to the Navy is an important part of the selection process. In many cases this may lead to selection of more mature technologies and less risk taking, trading a higher probability of success for a lower potential for payoff.

Air Force SBIR management is also very decentralized but nevertheless quite different from that of the Navy. The Air Force has program managers operating in two tiers. The top tier (at command level) reports to the Air Force SBIR program manager and the second tier (at lab level) reports to the first tier. Technical Officers within the labs write the topics. Approvals are made by the Lab Chief Scientist and generally supported by the Command Chief Scientist and the Air Force SBIR program managers although rewrites are sometimes required. Proposal approval is decentralized to the Directorate level. The Air Force awards Phase I for $100,000 for nine months rather than the nominal $75,000 for six months. The extra time and dollars help to bridge to Phase II. Technical officers are evaluated on their ability to transition technology; thus they have a bias toward helping SBIR to transition into the Air Force or commercially. Contractors claim that overall reductions in Air Force advanced development funding result in lab topics that cover work formerly done under the Air Force’s R&D program. Such topics are alleged to be difficult to commercialize.

The Army, on the other hand, centralizes topic, Phase I, and Phase II proposal selection; this centralized process began with FY 1992 topics and Phase I proposals in late 1992. As in the Air Force, topics are allocated to the laborato-

ries on the basis of the lab’s R&D budget.1 The Service calculates how much of the annual SBIR funding will be needed to fund new Phase II projects and to pay the second year of Phase II projects that were approved the prior year; then it determines how many Phase I contracts can be awarded with the remaining funds. Anticipating about 1.5 Phase I contracts per topic allows estimation of the number of topics that can be supported.2 Labs are also allocated backup topics in the event that their primary topics do not survive the centralized selection process. The Army ’s 10 senior scientists/technologists, who receive input from evaluators and managers at the laboratories, head the centralized selection of topics and proposals. The Director of the Army Research Office heads the Source Selection Board for Phase I. The Army SBIR process is not as formally connected to its acquisition community as is the case in the other Services.

Unlike the Services and other agencies, BMDO has a small number of broad topics. The topics are largely the same each year, evolving gradually from year to year, and providing great flexibility to proposing firms. Topic development and proposal decisions are centralized. Volunteer evaluators from the Services, DSWA, and BMDO assist in the evaluation and serve as technical monitors. Commercialization plans are an important factor in evaluation, with co-investment considered a strong indicator that commercialization will occur. Nevertheless, BMDO has a reputation for funding only high-risk projects.

In DARPA, topic selection and proposal decisions are decentralized to the Technical Office directors. In DSWA, the five technical Directorates control the topics, but the proposal decisions are made by a board composed of the deputies from each directorate.

BMDO allows all Phase I winners to submit Phase II proposals. All of the Services and other agencies invite proposals from firms that are doing well in Phase I. In both DSWA and the Army, the centralized decision process for Phase II only meets once a year, which delays the award of Phase II.

DoD conducts two SBIR solicitations a year, the first closing in January and the second closing in July. Solicitations announce the topics and provide directions and formats for submission of proposals. The Air Force and BMDO participate only in the first solicitation. The Army participates only in the second. The Navy and the other agencies participate in both solicitations.

Prior Commercialization Studies

In 1991, the General Accounting Office (GAO) conducted a study across all federal agencies (including DoD) that fund SBIR, to evaluate the aggregate com-

|

1 |

The Air Force also allocates the number of funded Phase I projects. |

|

2 |

The Navy allocates the money rather than the topics, allowing each command to determine how the money will be spent. Navy contractors sometimes experience a long time before Phase II approval or disapproval, implying that the awarding organization was waiting for the following year’s funding. |

mercial trends of products in the third phase of SBIR. The 1991 survey questionnaire was sent to all Phase II awardees from the first four years—1984 through 1987—in which the agencies made Phase II awards. GAO chose the earliest recipients because studies by experts on technology development concluded that five to nine years are needed for a company to progress from a concept to a commercial product. Their rationale for not including Phase II recipients from 1988 or later was that, in most cases, those project recipients had not had sufficient time to “make or break” themselves in Phase III. Responses to the GAO study indicated that 10 percent of the projects studied had not completed Phase II and even the earliest projects studied had had inadequate time to mature. Although upbeat about the overall early indications of commercialization, GAO expressed some concern over the rate of commercialization in DoD.

In 1996, the Deputy Director of Research and Engineering directed a study of commercialization of SBIR within DoD. The contractor3 used the same methodology and survey instrument that GAO had used five years earlier, for example, surveying all Phase II awardees through at least four years prior to the 1992 study. Use of this methodology allowed direct comparison of results. In 1998, the SBA employed the same contractor to survey Phase II winners from the other (non-DoD) 10 federal agencies.4 Once again the same methodology and survey instrument were used.

Several lessons from the earlier studies affected the survey conducted for this effort. In 1991, GAO allowed six months for responses and conducted three mailings of the survey as well as telephonic follow-up in selected cases. Despite this effort, 10 percent of the awardees could not be contacted because of bad addresses. In 1996, the second and third survey mailings were targeted after extensive phone contacts and use of the Internet to find firms who had not responded. Prior to any mailings, the 80 DoD offices that manage SBIR programs reviewed and updated SBIR firm addresses. After seven months of survey effort, one out of seven potential respondents still could not be located. Prior to the 1996 study, DoD was aware of a number of commercialization successes. Several had been uncovered by the GAO study and others were discovered by the Services in an unsystematic fashion. A number of these known successes did not respond to the survey, indicating that the absence of a response did not mean the absence of success.

The 1998 study required even more extensive effort to locate SBIR awardees. The SBA database of awardee addresses is not updated as frequently as that of DoD. Numerous mailings and phone calls and extensive Internet searches over 11 months could locate only three-fourths of the awardees.

The three earlier surveys demonstrated the mobility of award winners. Fre-

|

3 |

BRTRC of Fairfax, Virginia. DoD has not published the final report. |

|

4 |

Projects surveyed included those from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which no longer participates in SBIR. |

quently, firms had either grown or shrunken, ultimately requiring a move to a new facility. Often firms changed names because of new investment or products, or acquisition by a larger firm. Death and retirements contributed to economic reasons that firms went out of business. Principal investigators were often very mobile, reducing the value of their phone-contact information. Widespread changes to area codes and, to a lesser extent, zip codes, severed communications with firms that had not moved. The slow response by firms that did respond showed the value of follow-up calls and mailings.

Each of the prior surveys showed that most awards do not result in commercial sales. For the combined DoD and SB A studies, 61 percent reported no sales. At the other extreme, 4 percent of the projects were responsible for 75 percent of the commercial sales. The extreme divergence of these results raised questions about using a sampling scheme as a reliable measurement of sales. Each of the prior surveys measured the entire population being studied.

Fast Track

Subsequent to the GAO study, DoD initiated program changes designed to improve the rate of SBIR commercialization. Starting with the 1996 SBIR solicitations, DoD initiated a two year pilot policy—the SBIR Fast Track—under which SBIR projects that attract matching funds from third-party investors have a significantly higher probability of SBIR award, as well as expedited processing to reduce the delay in reaching the market. The purpose of the Fast Track policy is to concentrate SBIR funds on those R&D projects most likely to result in viable new products that DoD and others will buy.

At the conclusion of the initial pilot period, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology extended the Fast Track pilot for two additional years, because of the promising early results. The Under Secretary also directed an independent analysis of Fast Track. The National Research Council was asked to conduct that analysis, part of which is documented herein.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY AND ADMINISTRATION

Sample Selection

The selection of projects or firms for interviews and government technical monitors who would receive e-mail surveys began with the selection of a broad sample of SBIR projects for a mailed survey. The projects selected for this sample included DoD Fast Track award winners and BMDO-sponsored projects that had received co-investment funding. Other DoD projects, which were neither Fast Track nor co-investment, were selected as controls.

As indicated earlier, implementation of the Fast Track program began with the 1996 DoD solicitations. Because Phase I and Phase II normally last 6 and 24

FIGURE 1 SBIR Cycle for Solicitation 1, FY96

months respectively, and because the targets for proposal evaluation and award of those two phases are 4 and 6 months respectively, completion of Phase II of an SBIR project can be expected to take at least 40 months from the closing date of the solicitation. Thus the earliest FY 1996 projects could be expected to complete Phase II 40 months after the January 1996 closing of the first solicitation (i.e., May 1999) and the July 1996 closing of the second solicitation (i.e., December 1999).

Clearly, little time was available prior to the February 1999 mailing of the survey for the commercialization (Phase III) of projects that had resulted from the 1996 solicitations. Projects awarded as a result of the 1997 or later solicitations would have barely entered Phase II if at all by January 1999; thus the only Fast Track projects selected for the survey were those resulting from the 1996 solicitations. All 48 Fast Track projects for 1996 were selected. The life cycle for a typical SBIR project from the FY 1996 solicitation is shown in Figure 1.

The prior studies of SBIR commercialization by GAO in 1991 and by DoD in 1996 showed that it often takes several years after completion of Phase II before significant sales are achieved.5 There were no Fast Track firms that had

|

5 |

In interviews of 150 firms representing the majority of the DoD SBIR projects that had achieved sales by 1996, 58 percent said that it took over two years after Phase II to their first sale. On average, these 150 firms said it was 3.2 years after Phase II before significant sales occurred. |

had that much time to commercialize their Phase II.6 However, one DoD agency—BMDO—had begun an SBIR policy in 1992 that had some of the characteristics of the Fast Track. Two principal advantages of Fast Track are the validation of the commercial worthiness of the project by an outside source and the ability of the firm to use the Fast Track leveraging of funds to attract investors.

In the case of Fast Track, the willingness of the third party to invest its funds in the project is a strong indicator that the project will be a commercial success. The high likelihood that Fast Track projects will be awarded Phase II serves as a means to attract investors who are thereby provided an opportunity to leverage their investment because the government is matching between one to one and four to one in dollars.

The BMDO co-investment program also gives priority to firms that include co-investment in Phase II. The standard to be met is easier than for Fast Track because in-kind investments are acceptable (versus cash-only for Fast Track) and the investment may come from the SBIR firm rather than a third party. Nevertheless, the willingness of the firm to invest substantially in its own SBIR carries a strong message that it believes the project will be a commercial success. Some of the BMDO awardees use the prospect of leverage as a means to attract third-party investment. BMDO began the co-investment policy with the 1992 solicitation. For 1992, slightly less than one-third of its SBIR Phase II awards involved coinvestment. From 1993 to 1996, between 83 and 94 percent of the BMDO awardees included co-investment.

The 1996 DoD SBIR study showed that most SBIR projects require an additional investment at least equal to the amount of the combined Phase I and II to succeed commercially. Over 60 percent of the DoD projects surveyed in 1996 failed to commercialize. Few of those unsuccessful projects attracted additional investment (third-party or internal). Conversely, almost all of the successful projects had either internal or external additional investment. Commercialization success was better correlated to the size of additional investment than to the source (internal or external) of that investment. The study could not determine whether the additional investment caused the commercialization success or whether the commercialization potential of the project caused the additional investment to occur. Because both Fast Track and BMDO co-investment projects have additional investment, it can be hypothesized that they will be more likely to experience commercial success than the average DoD project.7

|

6 |

As a general rule, Phase II awards occur one or two fiscal years after a solicitation. The GAO methodology for sample selection picked projects whose Phase II began four years prior to its 1991 survey; thus the solicitations for the projects in the GAO sample were released at least five years before the survey. Using the GAO methodology, projects resulting from both the 1996 and the 1995 DoD solicitations would have been considered too immature to be evaluated for commercialization results. |

|

7 |

Commercialization results of BMDO projects receiving Phase II awards from 1984 to 1992 were at least as good as the results of the rest of the DoD projects. |

Although there are significant differences in the implementation of Fast Track and the BMDO co-investment policies, this study tested the assumption that BMDO co-investment projects could be used as a surrogate for Fast Track for the years 1992-1995 when Fast Track did not exist. Examination of projects from these earlier years provided a greater opportunity to find actual commercialization results. In 1996, ten BMDO Phase II projects used Fast Track and 22 others included co-investment. The survey sample included all 127 BMDO co-investment projects awarded from the 1992–1996 solicitations.

Determination of whether Fast Track or BMDO co-investment policies result in selection of projects that achieve greater commercialization success than the general population of DoD SBIR projects necessitated selection of a matched control group.

The Fast Track control group was structured to be similar to the 48 FY 1996 Fast Track awards, matching, to as great an extent as possible, the solicitation fiscal year, the number of prior Phase II awards received by the firm, the size of the firm, the location (state) of the firm, the awarding agency, the closing date of the solicitation, whether the firm was designated as woman- or minority owned, and the technology area of the project.

For BMDO co-investment projects in FY 1992, all matches were made with BMDO non-co-investment projects. Beginning with FY 1993, the vast majority of all BMDO awards were co-investment; thus matches for FY 1993 through FY 1996 had to be made with projects from other agencies. Generally, the match was made with the Service that was managing the Fast Track contract for BMDO8 or with DARPA projects being managed by that Service. The latter —that is, DARPA—was the preferred match.

Inclusion of all Fast Track and BMDO co-investment Phase II awards from the 1996 or earlier DoD solicitations provided a nonrandom sample. Similarly, the one-for-one matching of a project in the control group based on the characteristics described earlier was not a random selection. The diversity of the population of SBIR awardees was such that it was impossible to match all characteristics project by project. The order in which the characteristics are listed above is the order of priority for matching.

In selecting the control-group projects, each solicitation year was drawn separately to ensure that the aggregate characteristics matched. Thus the 70 projects picked for 1996 in aggregate matched the 48 Fast Track plus 22 BMDO projects

|

8 |

The projects of each Service (Army, Navy, and Air Force) are managed by that Service. Each Service has its own contracting agencies. Although the same rules apply, there are procedural differences between contracting agencies in the same Service, and especially between Services. BMDO does not have its own contracting agency; it often uses a technical monitor from one of the Services and always uses one of the Services ’ contracting agencies (normally the contracting agency that supports the technical monitor). DARPA similarly uses the Services for contracting and technical manager; thus its projects were often selected as a match for a BMDO project. |

as closely as possible. A similar process was conducted for each solicitation year. In aggregate, the 175 control projects that were initially selected matched the Fast Track and BMDO co-investment projects fairly well in all the characteristics mentioned above except for agency (because of the lack of BMDO projects that were not co-investment).

Matching a Fast Track project with a non-Fast Track one that has similar characteristics was useful for comparing the performance of like firms, only one of which obtained matching funds before Phase II. Thus the initially constructed control group mirrored the projects under study. In several respects, however, Fast Track firms were different from the average firm that had been winning Phase II awards.

We postulated that the Fast Track policy might attract a different kind of firm to the program, replacing firms that would have won in the absence of Fast Track. If this were true, then the control group should be representative of the entire population of Phase II winners. Two related characteristics of the Fast Track winners and the initially selected control group that differed from those of awardees in the program as a whole were the number of prior Phase II awards received and the size of the firm: Thirty-four of the 48 Fast Track firms (71 percent) had had no previous Phase II awards. For the Phase II population, the number of first-time winners was about 40 percent. At the other extreme, the control group did not include the program’s most frequent winner because the most prior awards by a Fast Track or co-investment firm was one-third the number of prior awards received by that most frequent winner.

First-time winners tend to be new, and thus small, firms. The high percentage of first-time winners among the Fast Track firms meant that the average size of the Fast Track firms tended to be smaller than the average size of the overall Phase II population of firms as a whole. After discussions with the SBIR Program Director in the DoD Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization, it was decided to increase the representativeness of the control group by adding projects that would result in characteristics similar to those of the Phase II population as a whole. In this fashion, the Fast Track performance could be compared to either that of similar firms (initial sample) or to that of the SBIR population as a whole (expanded sample).

Additional projects were added to each year of the control group in a modified random fashion. First, the average characteristics (number of prior Phase II awards, size of firm, state, minority or woman ownership, and agency) of all DoD Phase II projects for a specific year were determined. In an iterative fashion an estimate was made of how many projects would have to be added to the control group, and the expected distribution was calculated using the average characteristics. The expected distribution was compared to the initial control group to determine the variance between them. The goal was to reduce the variance to the minimum solely by adding projects to the initial control group. If the initial estimate of the number of projects to be added did not reduce the variance enough,

a larger estimate was investigated in a similar fashion. The result was the number of projects that needed to be added to the sample and a compilation of their aggregate characteristics.

Next, all Phase II projects from that year that were not yet in the study sample or control group were listed in a random order by a random number generator. The analyst went through the list in that random order to select additional projects. Each project that met or nearly met the desired criteria was added to the sample until the desired number had been selected. This process was completed for each year in the sample, resulting in the addition of 29 projects to the original control group for a total control group size of 204.

The surveys (one per project) were mailed to the 298 firms conducting the 379 projects (control group plus study sample) on February 3, 1999. The characteristics of the firms in the sample are described in Appendix A. This sample was used to mail out the survey and as a basis for selection of firms to be interviewed. Project information, including addresses, principal investigators, and phone numbers, all of the characteristics used in matching, as well as other information in the database such as award amounts, dates, contract numbers, and scheduled durations were provided to the investigators to assist in selection of firms for interviews. Information was also provided to allow survey of the government technical points of contact.

Administration of the Survey

The questionnaire was derived from the one used in the 1996 and 1998 studies (which were substantially the same as the questionnaire for the 1991 GAO study). Fifteen of the 27 questions from the earlier DoD study formed the basis of this questionnaire. Questions that the earlier studies had answered and that were unlikely to yield new information were eliminated. The researchers added 14 new questions to attempt to find leading indicators of potential commercial success or to otherwise differentiate Fast Track firms and projects. Many of the resulting 29 questions had multiple parts.

The formatting, printing, mailing, and other administrative aspects of the survey including scanning results to a database was subcontracted to Questar in Eagan, Minnesota. The final questionnaire is contained in Appendix B.

An advance letter from the DoD SBIR/Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Program Director, Jonathan Baron, was sent to each selected firm one week prior to the survey. The letter described the purpose and importance of the study and requested cooperation in survey completion and participation in subsequent interviews. Selected firms also received a letter from the Board on Science, Technology, and Economic Policy of the National Research Council that gave further description of how projects were chosen and why the survey and interview input was needed.

As expected from the earlier studies, a number of advance letters and surveys

were returned as undeliverable. As each was returned, the firm was looked up in Internet yellow pages. If a new address and phone number were found, the firm was contacted to verify that it was indeed the correct firm and, where possible, a point of contact (POC) was obtained. When the Internet did not list an address, an attempt was made to contact the principal investigator or other POC listed in the DoD database. Surveys were then re-addressed and mailed.

The very short time available for this survey necessitated sending a second mailing after only about 6 percent of the surveys had been received. About that time, researchers began reporting that many of the firms that they had tried to contact had new addresses or phone numbers. BRTRC then began calling every firm to verify that the survey had been received and to encourage that it be completed. Many contacts indicated nonreceipt, resulting in additional mailings targeted to the contact. Many phone numbers turned out to be dead ends, resulting in further Internet searches. Still other POCs had phone numbers that seemed correct, but they were never present and did not return calls. A targeted third mailing was sent out as well as additional individual mailings. During the final week of the survey, repeated calls were made to the Fast Track firms who had not responded. In some cases new surveys were sent by fax, and returns were accepted by fax.

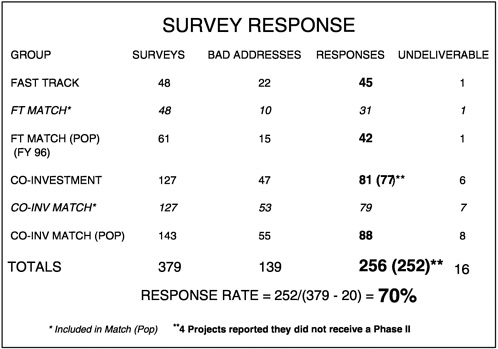

By June 21, four and one-half months into the survey, 256 responses had been received. The original 182 bad addresses had been reduced to 16 undeliverables. Fifty-four percent of the responses showed new addressees. Four respondents indicated that no Phase II had been awarded. Using the same methodology as the GAO had used in 1992, undeliverables, non-Phase II, and out-of-business firms were eliminated prior to determining the response rate. Although 379 projects were surveyed, 20 were eliminated as described. This left 359 projects, of which 252 responded (256 – 4), representing a 70 percent response rate. Considering the length of the survey and its voluntary nature, this rate was relatively high and reflects both the interest of the participants in the SBIR program and the extensive follow-up efforts. This response rate provides a credible basis for evaluation. The six sample groupings and their address and response data are shown in Figure 2.

ANALYSIS OF SURVEY RESPONSES

This section displays the responses for four of the above sample groups: Fast Track, the Fast Track Population Match (referred to as 96 Control group), the BMDO Co-investment group, and the population-matched control group for BMDO (BMDO Control group). Complete survey responses are included as Appendix C.

FIGURE 2 Survey Response Analysis

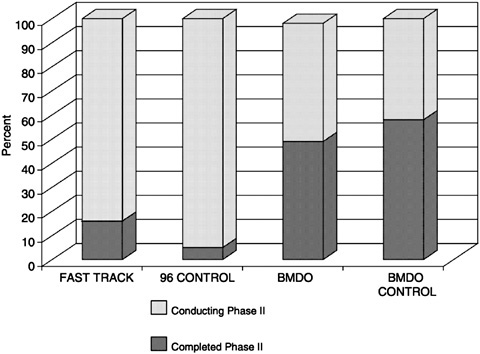

Phase II Completion

The short time frame from the solicitation for Fast Track to the completion of the survey had the expected result that most Fast Track projects had not yet completed Phase II. The 96 Control group fared even worse. As shown in Figure 3, only 16 percent of the Fast Track projects had completed Phase II prior to completion of the survey. For the 96 Control group, Phase II completion was only 5 percent.

The Phase II completion rate for the BMDO co-investment and its BMDO control group was slightly lower than expected. Part of this lower rate is due to a lower response rate from the older projects (more likely to be completed) than from more recent projects. Another factor contributing to the slow pace of these two groups was the delay between Phase I completion and the award of Phase II. For the BMDO Control group this delay averaged 8.9 months. For the BMDO Co-investment group, the delay averaged 10.3 months. Part of the delay is due to the government evaluation and award process and part is due to the time lag from completion of Phase I until the contractor submits its Phase II proposal. For these two groups the contractor proposal portion of the delay averaged three months.

Changes in the Phase II award process were instituted in 1996 in an attempt to reduce the average delay for evaluation and Phase II award to less than six

FIGURE 3 Status of Phase II

months. The total average delay for the 96 Control group was reported as 6 months. Proposal submission delay was less than one month. For Fast Track, Phase II proposals must be submitted during Phase I; thus there is no delay due to proposal submission. The reported delay for evaluation and award for Fast Track Phase II was 2.4 months. Government evaluation and award for FY 1996 Fast Track was accomplished in one-half of the time required for government evaluation and award of the 96 Control group, fulfilling the promised expedited treatment of Fast Track Phase II proposals.

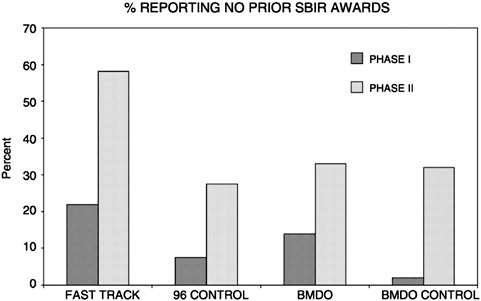

Validation of Sample Selection Factors

Two of the factors used in sample selection were number of Prior Phase II awards and size of the firm. Both of these factors were examined in the survey. The DoD database tracked the number of DoD Phase II awards received by each firm. On the basis of this measure, 71 percent of the Fast Track firms had no prior Phase II awards. On average overall for DoD Phase II award winners, about 40 percent have had no prior DoD Phase II awards. In the survey, respondents were asked about prior Phase I and Phase II awards from any federal agency (including DoD). Results are displayed in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4 Prior SBIR Experience

Despite inclusion of awards from other agencies, the Fast Track group still reported that a high number of awardees (58 percent) had no prior Phase II award. The other sample groups showed more experience, with an average of about 30 percent reporting no prior Phase II award. Even the Fast Track firms were not inexperienced in SBIR. Seventy-six percent reported receiving a prior Phase I award. Forty percent of the Fast Track winners had three or more prior Phase I awards. One firm, which was awarded three Fast Track Phase II contracts, had had 14 prior Phase II awards. Over half of the average number of prior Phase II awards (1.8) per project for Fast Track are accounted for by this firm.9 The 96 Control group reported the lowest percent of firms that had no prior Phase II, and the highest average number (14.7) of prior Phase II awards. Over half of that average can also be attributed to three projects, one awarded to each of three frequent winners.

The BMDO Co-investment group reported an average of 8.5 prior Phase II awards. Its control group averaged 10 prior Phase II awards. Each of these averages was also skewed by a few frequent winners.

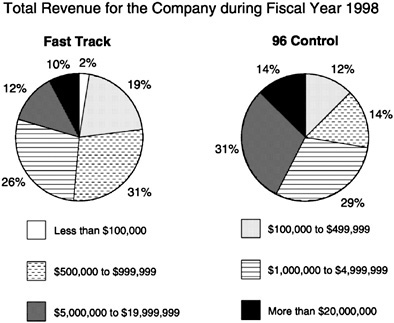

A second selection factor was the size of the firm. The number of employees in the DoD database was used to measure firm size. Respondents identified firm

|

9 |

Each of Digital System Resources’ three projects reported 14 prior Phase II awards, thus the same 14 awards count three times in calculating the project average. |

FIGURE 5 Annual Revenue Comparison

size using the metric of annual sales. Figure 5 shows the results for Fast Track and the 96 Control group.

Figure 5 shows that the annual revenue for Fast Track firms is considerably less than for the 96 Control group. Only 22 percent of the Fast Track firms reported over 5 million dollars in annual revenue compared to 45 percent for the 96 Control group. Fifty-two percent of the Fast Track firms reported less than 1 million dollars in annual revenue compared to 26 percent of the 96 Control group.10

The DoD database does not contain information on the age of the firm, but the survey elicited this information. The median founding date for the BMDO Co-investment respondents and for the BMDO Control group respondents was 1989. For the 96 Control group, 1985 was the median founding year. Fast Track firms were much younger; half were founded in 1994 or later.

|

10 |

The 40 respondents of the 96 Control group consisted of 29 respondents originally matched to Fast Track projects and 11 from projects that had been added to make the control group match the population. The original 29 control group respondents had smaller annual revenues than the population, but larger than the Fast Track group. Of the 29 firms, 10 reported over $5,000,000 in annual revenues and 9 reported less than $1,000,000. |

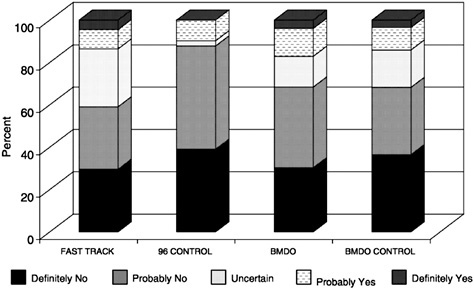

FIGURE 6 Would the Company Have Undertaken Project without SBIR?

Would They Have Done It Without SBIR?

When we attribute sales or other economic activity, we must consider whether these sales would have occurred in the absence of SBIR. Figure 6 displays responses to the question of whether the company would have undertaken the project in the absence of SBIR.

The Fast Track group is far less certain that they would not have undertaken the project without SBIR than any of the other three groups. Only 59 percent of the Fast Track firms state that they definitely or probably would not have undertaken the project without SBIR. Eighty-eight percent of the 96 Control group would not have undertaken the project. However, only 14 percent of the Fast Track respondents said that they definitely or probably would have undertaken the project in the absence of the SBIR. This percentage is surprisingly low given that each of the Fast Track awardees was able to raise third-party funding for their projects. The large number of uncertain answers from Fast Track firms may indicate that they were not sure the third party would have invested without Fast Track.

These answers indicate that the SBIR program is clearly funding projects that would not be undertaken without SBIR. Even projects that would have been undertaken are affected by SBIR. In earlier interviews, two awardees that had significant commercial success indicated that although they definitely or prob-

FIGURE 7 Expected Products of the SBIR

ably would have undertaken the project without SBIR, they would not have experienced the same level of success. One stated that the SBIR award gained at least two years for them and that a time delay would have substantially reduced their market share. Another attributed to SBIR the flexibility to try a higher-risk approach than would have been possible with private funding. That higher risk resulted in a lower-cost product and consequent higher sales.11

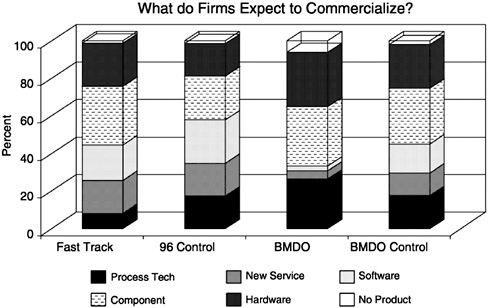

Expected and Achieved Commercialization

Respondents were asked to identify the product that they expected to commercialize from their SBIR project. Very few did not expect to achieve a product. This optimism stands in contrast to earlier studies that have shown that only about 40 percent of the SBIR projects achieve product sales. Figure 7 breaks out the types of products expected. Hardware and hardware components account for the largest number of expected products. Software is the second most anticipated product for all groups except for the Co-investment group, which expects little software, but a large amount of process technology.

|

11 |

These respondents were Optiva Corporation of Washington State, which reported $240,000,000 in sales, and Genosys Biotechnologies of Texas, which reported $60,000,000 in sales during the SBA Commercialization Study. |

FIGURE 8 Sales through May 1999

Figure 8 displays the commercialization that has already been achieved for these projects. The much smaller achievement than projected is largely explained by the low number of these projects that have completed Phase II (Figure 2).

Products in Figure 8 include both hardware and software. The strong showing for services may imply that services can be commercialized faster than products or processes. It would appear in comparing Figure 7 and Figure 8 that most, if not all, anticipated commercialization of services has already occurred. There is some distortion, however in each of these figures. Respondents were allowed more than one answer to each of these questions. For example, the 45 Fast Track respondents identified 74 products in 15 distinct combinations such as component, hardware product and software, software only, hardware and process, or software and service. The percentages shown are calculated against the total number of responses rather than the total number of respondents.

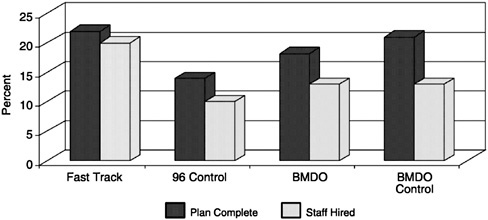

The performance levels in Figure 8 are consistent with the reported amount of completed marketing activities that are displayed in Figure 9. Fast Track projects reported the highest levels of completed marketing plans and the highest levels of marketing staff hired.

FIGURE 9 Percent of Firms that Completed Marketing Activities

Impact of Funding Gap

Fast Track was one of two reforms initiated in FY 1996 as a result of the 1995 DoD Process Action Team findings on the SBIR program that impacted the funding gap between Phase I and Phase II. The requirement for a Fast Track contractor to submit its Phase II proposal during Phase I and for the agency to expedite evaluation and award of Fast Track proposals should have reduced the Fast Track funding gap between the two phases. The second reform affecting the gap was establishment of a new standard of six months for the average time interval between receipt of an SBIR proposal and award in Phase II.

Funding gaps make it difficult for a small company to keep its research team together, and studies have shown that delay in time to market decreases the value of an innovation. The funding gap is addressed on the next two charts. Figure 10 shows the magnitude of the gap, and Figure 11 shows the number of firms experiencing a gap and how the firms dealt with the gap.

Figure 10 displays the lowest, highest, and average funding gaps (in months) reported for each group, for those projects that reported experiencing a funding gap. For Fast Track, 23 of the 45 respondents experienced no gap; thus the average gap for all Fast Track respondents was only 2.4 months. For the 96 Control group, ten projects reported no gap, resulting in an average gap for all 96 Control group respondents of 4.7 months. The percentage of projects that reported a gap in each group is shown in Figure 11.

Only four Fast Track projects (9 percent) reported that the funding gap caused them to stop work. Over half of the 96 Control group had to stop work because of the funding gap. The use of bridge funding was much more prevalent in Fast

Track than in any other group. According to program managers, the use of bridge funding is not limited to Fast Track. For the solicitation years 1992 to 1996, however, only 5 percent of the non-Fast Track projects reported that they received bridge funding, and over 43 percent of the non-Fast Track projects had to stop work awaiting the award of Phase II.

Additional Developmental Funding

SBIR does not provide federal funds to commercialize a product. Seldom can a firm go directly from Phase II to a commercial product. Further development, testing, standardization, producibility engineering, Beta testing of software, and similar activities usually are not performed until after Phase II. Activities related to market research, trade-show attendance, advertising, and sales are not allowable costs under SBIR. Generally, additional developmental funding must be at least as large as the SBIR awards for successful commercialization to occur. It is not unusual for an SBIR firm to use a prototype developed during Phase II to attract investors or customers who place an order for the further development and delivery of a product. Some necessary development activities may occur concurrently with early sales, with the revenue used to upgrade later versions of the product. However, most additional investment must happen early in the sales cycle. The reported additional non-SBIR development funding to date is shown in Figure 12.

Most private additional developmental funding is invested in anticipation of a return on investment. Thus the additional investment is a leading indicator of ultimate commercial sales.

Higher investment in Fast Track projects than in the projects of the 96 Control group is a foregone conclusion at this point. Fast Track projects had to bring third-party money to the table and have it invested early in Phase II. The control group projects did not. The earlier timing of investment in Fast Track would not necessarily mean higher ultimate commercialization. When compared to the coinvestment projects, which also brought money to the table, and to the BMDO Control group, another conclusion emerges. The projects in these latter two groups, on average, were two years older than the Fast Track projects, yet their average additional developmental funding was half that of Fast Track projects. It would appear that in addition to occurring earlier, the ultimate investment in Fast track projects will be larger than in non-Fast Track ones.12

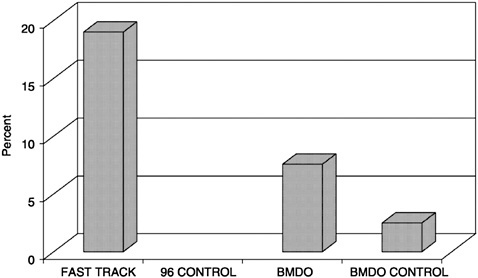

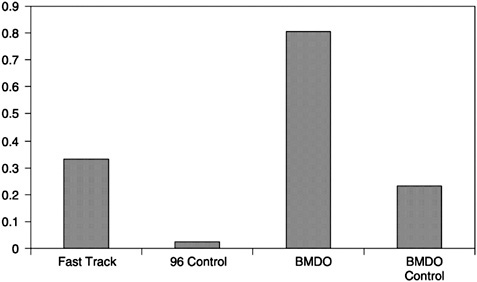

An examination of the sources of the additional funding reveals a significant difference between Fast Track and the other groups. Figure 13 looks at the percentage of projects that reported receipt of venture capital investment.

|

12 |

The 1996 DoD Commercialization Study found that DoD projects awarded Phase II from 1984 to 1992 averaged $597,000 in additional non-SBIR developmental funding. |

In the 1996 DoD SBIR Commercialization Study, only 3 percent of the projects reported receiving venture capital. The low reports of venture capital for the two control groups (0 and 2.5 percent) are consistent with the earlier study. For the BMDO Co-investment group, the level of venture capital (6 of 77) is significantly different from that in the earlier study at a 5 percent confidence level, but not at the 1 percent level. The level of Fast Track venture capital (8 of 45) is significantly different from that in the earlier study.13

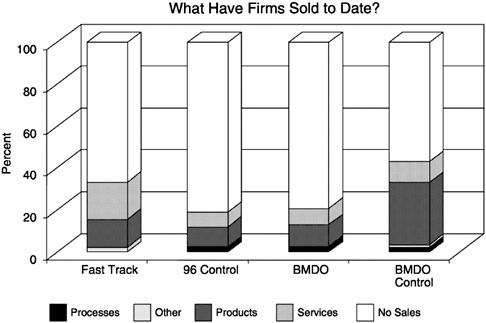

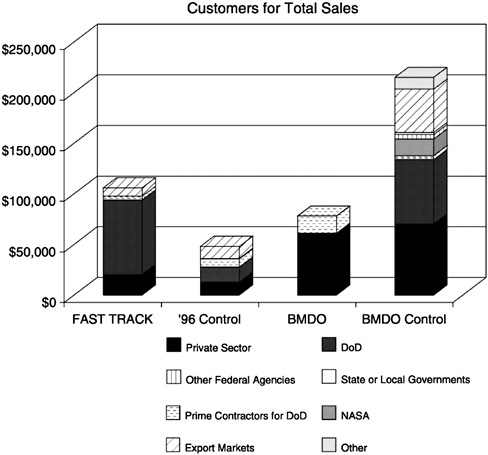

Sales

Although it is too early for meaningful sales comparisons when so few projects have even completed Phase II, companies did report that some sales have already occurred. The sales and the customers for those sales are shown in Figure 14.

Three of the 11 Fast Track projects reporting sales account for two-thirds of the sales. All three projects are still in Phase II and are being performed by the same contractor, Digital System Resources. In each case the sales were entirely to DoD, and in each case, a Navy program office is providing the third-party funding.

The low level of sales for all groups is not unexpected because most of these projects are still in Phase II, and even those that completed Phase II have had little time to achieve sales. At this time, projections of sales are probably a better indicator than achieved sales. Figure 15 shows the projected sales through the end of the year 2001. Because most surveys were prepared in March and April 1999, this represents a sales projection for the next 11 quarters. In addition to the 11 Fast Track projects that have experienced sales, 8 expect their first sale in 1999, and 14 more expect sales in 2000. A total of 37 of the 45 expect to have had sales by 2001. For the 96 Control group, 8 have sales to date, with 6 more projecting sales in 1999 and 12 projecting sales in 2000. For this Control group, 30 of the 42 plan to have made sales by 2001.

On the basis of the 1996 and 1998 SBIR commercialization studies, it is not unreasonable to project an eventual average sale in excess of $1,000,000 per DoD SBIR project. To expect $1.2 million in sales in the first five years after the 1996 solicitation is probably overly optimistic for the 96 Control group. The more mature BMDO control group is likely to have higher sales in that time frame because to date it has reported more than double the investment and four times the sales of the 96 Control group. However, 3 million dollars in sales projected for the BMDO Control group appears to be even more optimistic. There is no reason to assume that these control groups would perform that much better than past SBIR winners. Such optimism, however, is normal among SBIR partici-

|

13 |

Question 13 of the survey asked Fast Track recipients to identify the source of matching funds in the proposal. Thirteen of the Fast Track respondents marked the venture capital response. Five of these 13 used that response because there was no alternative listed for private investor in question 13. |

FIGURE 14 Sales as of May 1999

pants. Optimism in projected SBIR sales appeared in the 1991 GAO study. The level of sales projected to be achieved in two years in that study actually took five years to achieve.14

For Fast Track, the high levels of investment early in the development cycle and the marketing activities already completed add credibility to a projection of much higher than average sales; however, the 8 1/2 million dollars in projected average sales is unlikely to be achieved in the next three years. The relative relationship of the projected performance for the next three years of each of the groups is more likely to be valid than the absolute sales projected. The seven-to-one advantage projected for Fast Track over its control group in sales projected for the next three years should not be extrapolated to mean seven times as much in

|

14 |

As measured in the 1996 study. |

FIGURE 15 Expected Sales through 2001

eventual total sales. Fast Track projects are currently ahead of the 96 Control group in projects that have completed Phase II and projects that have had sales, and they are substantially ahead in additional developmental funding to date. Over time, some of the gap between the two groups should close.

Comparison of Performance and Group Characteristics

Several questions were asked of the respondents to identify differences among groups to see if the difference might correlate to performance of that group. The responses to Additional Developmental Funding (Figure 12), Total Sales (Figure 14), and Expected Sales (Figure 15) each show significantly better performance for Fast Track than for its 96 Control group. Because the greatest difference is in the Expected Sales, that parameter was chosen for this comparison.

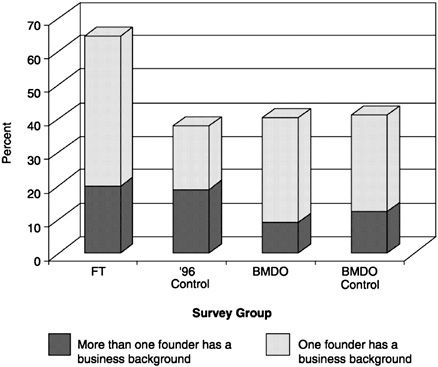

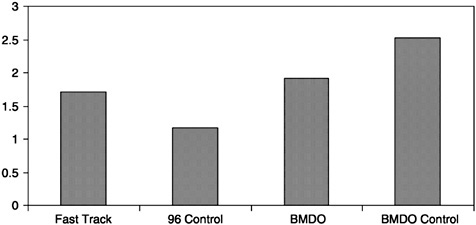

Respondents provided information on their firm’s founders, specifically on their business background and the number of other companies started by one or more of the founders. Figure 16 demonstrates that one or more founders was more likely to have a business background from firms in the Fast Track group than from firms in the other groups.

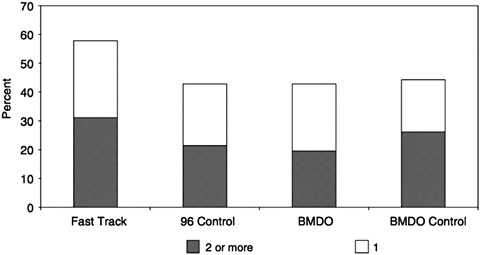

Examination of the number of other companies founded by one or more of the founders produces a very similar chart (Figure 17). On average, the founders

of each Fast Track firm started 2.1 other companies. Founders of each BMDO co-investment firm started an average of 0.9 other companies while the average number of companies started by the founders of a firm in either of the two control groups was 1.3.

Comparison of the business background of the Fast Track firms to the reported expected sales yielded an interesting result. The 29 Fast Track firms where one or more founders have a business background expect average sales in the next three years of $11.4 million. The Fast Track firms that did not report having a founder with prior business background expect only $3.0 million in that time frame.

Fast Track firms whose founders had started one or more other firms report that they expect an even higher level of sales. Specifically, the 24 firms whose founders started other firms anticipate $13.5 million in sales in the next three years compared to the $1.6 million expected by firms whose founders had not started other companies.

These apparently strong correlations do not extend to the same extent to the other three groups. For the BMDO Co-investment group, average expected sales for the business-background firms is higher ($6.5 million) than for the firms whose founders have a nonbusiness-background ($2.7 million). However, for both control groups, there was essentially no difference between firms where the founders had a business background and those where they did not. The firms whose founders had started other firms in the 96 Control group predicted sales that were three times as great as other firms in that group, but for both BMDO and its control group, sales were essentially the same for the two types of firms.

For Fast Track, the business background and experience in starting other companies may have been quite useful in obtaining the third-party financing. Because such third-party financing was required to be in Fast Track, this could account for the high percentages on Figure 16 and Figure 17. The business-background Fast Track firms attracted six times as much investment to date as the nonbusiness-background Fast Track firms. The Fast Track firms whose founders started other companies attracted two and one-half times as much investment as the Fast Track firms whose founders had not started other companies.

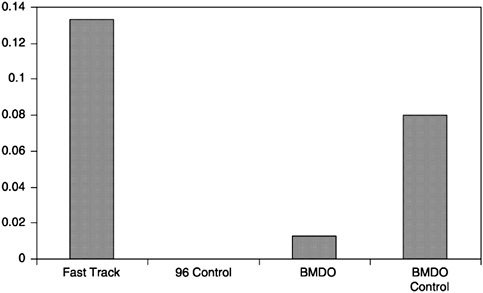

Patents, Copyrights, and Scientific Publications

Intellectual property is a primary product of the SBIR program to many firms. Patents and copyrights are a means to protect such property. The number of patents and copyrights applied for and issued is a measure of the intellectual property being generated. Since most scientific journals are refereed, the number of publications submitted and published measures to some degree the scientific merit of the SBIR. The numbers of patents, copyrights, and scientific publications to date, as measured by the survey, are shown in figure 18, figure 19, and figure 20, respectively.

FIGURE 20 Average Number of Publications per Project

A concern expressed by some opponents of Fast Track is that, in order to attract third-party investors, there can be no true research in a Fast Track SBIR. The project must be much further down the development path. They contend that to obtain third-party financing innovation must be complete or nearly complete and the SBIR merely serves to validate it. If this is the case, one might expect a lower level of patent and copyright activity for Fast Track.

The first point to note in Figure 18 and Figure 19 is the low average level of activity for all groups. Recall that only 16 percent of Fast Track projects have completed Phase II. Patenting is not a quick process. The BMDO and BMDO Control groups have had more time, but only half of those projects are out of Phase II. It is not unusual for a patent to take a year or more for approval after the completed application is submitted. (The application process is also time- and resource-consuming.) For Fast Track, 30 percent of the patent applications submitted so far have completed the approval process. For both BMDO groups, half of the applications have already been approved. The 96 Control group has submitted slightly over one-third as many patent applications as the Fast Track group, but none has yet been approved.

It would seem that Fast Track is outperforming its control group and BMDO Co-investment is outperforming BMDO Control in patents. The BMDO advantage over Fast Track is probably due to the extra time those projects have had. Conclusions about technical merit are premature. The limited time that projects have had for patent activities and the small numbers of patents issued so far makes any analysis at this time questionable. The number of copyrights issued also is too small for any meaningful comparison.

Activity in average scientific publications per project would seem to show Fast Track outperforming its control group (see Figure 20). Fifty-four percent of the Fast Track publications, however, come from a single project. When we eliminate this outlier and similarly eliminate the one 96 Control project that accounted for 30 percent of that group’s publications, the averages are 0.8 and 0.8 publications per project, respectively. A similar elimination of the top 3 to 4 percent of the projections from the other two groups would halve their averages. Beyond concluding that those projects that have had longer time to mature have published more, it is difficult to draw more from these data.

Initial Public Stock Offerings (IPOs)

None of the Fast Track or 96 Control group firms has yet made an IPO. Four firms from the BMDO Co-investment group and one BMDO Control group firm have made IPOs. A logical explanation for the difference between Fast Track and BMDO groups is the age and revenue levels of the firms and the larger size of the BMDO groups. This explanation does not account for the 96 Control group, which is older than and has revenues equal to or higher than those of the BMDO groups. One Fast Track firm and one firm from each BMDO group plans an IPO this year.

Sale of Ownership

SBIR contractors are often reluctant to seek third-party financing, particularly from venture capitalists, for fear that they will lose control of their firms. Others welcome such cash infusions, preferring to have partial control over a large firm to full control of a small one. Some of this latter group intend to sell their interests as the firm gets large and roll the profits into starting a new firm. Those leery of venture capital are often heavily involved in advancing technology and less interested in production. They are afraid that outside investors would change the fundamental nature of the firm. The business expertise that venture capital insists on putting in place (if not already there) creates an environment likely to produce commercial success, but such success may not be the principal goal of the owners.

Respondents were asked to identify activities related to sale of partial ownership. Finalized agreements and ongoing negotiations are shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21 portrays the “cost” to firm owners of Fast Track firms. To obtain third-party funding, they may be limiting their personal share of the potential gain from their innovation by selling a share of their firm. However, they may also be increasing the ultimate gain from the innovation by infusing cash and business expertise at the critical point in development. Whether this is a cost or an opportunity is very much a personal evaluation.

FIGURE 21 Sale of Partial Ownership

CONCLUSIONS

Past studies of SBIR commercialization has used three primary measurements of success: sales, additional developmental funding, and expected sales. By each of these measures, the Fast Track projects are clearly outperforming those in the control group.

Although Fast Track sales lag behind those of the BMDO Co-investment group (which on average started two years earlier), they exceed those of the BMDO Control group, which had a similar head start. Moreover, Fast Track projects have achieved double the additional developmental funding of either BMDO group, and Fast Track projects expect twice as much sales in the next three years.

Fast Track has been successful in nearly eliminating the funding gap between Phases I and II.

Firms that apply for Fast Track tend to be much younger than average SBIR firms. They have had far fewer Phase II awards than the overall population. Sixty percent have had no prior Phase II awards. The average annual revenue for Fast Track applicants is less. These characteristics may have little to do with success and may change if the cost-matching arrangement is changed.

The predominance of firms in Fast Track whose founders have business backgrounds and firms whose founders have started other firms may indicate that such firms have an easier time acquiring third-party funding.

Additional developmental funding is a leading indicator of commercial success. High expectations of sales are probably better than low expectations, but the bottom line is sales achieved, and it is several years too early to measure that bottom line. Given the inherent risk associated with research-driven business, today’s high expectations for future sales may not be realized. A follow-up effort should be planned to verify the current conclusions.

Whether it is the validation of a third party to the commercial potential, the timing and magnitude of the additional funding, or merely the reduction in funding gap that contributes most to the apparent performance of projects selected for SBIR award under Fast Track, the program is working. Fast Track is selecting projects that should succeed in commercialization, and it is apparently contributing to their success.

APPENDIX A

Sample Characteristics

The survey sample of 379 projects consisted of a study group - 48 Fast Track Phase II (all of the Fast Track winners from 1996 DoD solicitations), 127 BMDO co-investment Phase II (all BMDO co-investment projects from the 1992–1996 solicitations) and 204 control group projects chosen from DoD 1992–1996 Phase II winners.

The Table below shows the firm size and the sponsoring agencies for the study sample projects and the control group compared to the expected distribution of 204 projects drawn at random from the Phase II award winners resulting from the 1992–1996 DoD solicitations.

TABLE A1 Firm Size and Awarding Agencies of Survey Sample

|

Firm Size # of Employees |

# of Firms Expected from Population |

# of Firms In Control Group |

# of Firms In Study Group |

|

1 to 5 |

45 |

48 |

57 |

|

6 to 20 |

63 |

61 |

72 |

|

21 to 50 |

35 |

44 |

21 |

|

51 to150 |

38 |

27 |

18 |

|

150 to 500 |

23 |

24 |

7 |

|

204 |

204 |

175 |

|

|

AGENCY |

|||

|

AF |

80 |

62 |

4 |

|

ARMY |

38 |

24 |

20 |

|

BMDO |

16 |

29 |

137* |

|

DARPA |

24 |

44 |

5 |

|

NAVY |

41 |

36 |

6 |

|

DSWA |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

OSD |

3 |

5 |

3 |

|

204 |

204 |

175 |

|

|

*The 137 BMDO projects are 10 Fast Track projects awarded by BMDO and 127 BMDO co-investment projects. All projects listed for other agencies in the study group are Fast Track. |

|||

TABLE A2 Representation of Woman and Minority Owned Firms

|

Number of Firms Owned By |

# of Projects Expected from Population |

# of Projects In Control Group |

# of Projects In Study Group |

|

Women |

18 |

22 |

17 |

|

Minority |

31 |

34 |

33 |

The distribution of firms owned by women or minorities in the study sample and the control group was similar to what would be expected from the population.

TABLE A2 Number of Phase II Awarded Prior to the Selected Project

|

Number of Prior PH II Received By Firm |

# of Projects Expected from Population |

# of Projects In Control Group |

# of Projects In Study Group |

|

0 |

81 |

86 |

85 |

|

1 |

25 |

24 |

20 |

|

2 |

16 |

12 |

16 |

|

3 |

12 |

11 |

11 |

|

4 |

9 |

7 |

4 |

|

5 |

9 |

11 |

7 |

|

6 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

|

7 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

8 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

|

9 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

10 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

11 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

|

12 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

|

13 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

|

14 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

15 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

16 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

17 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

|

18 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

19-29 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

|

30-74 |

7 |

7 |

1 |

|

>75 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

Total |

204 |

204 |

175 |

Thirty-four of the forty–eight 1996 Fast Track Phase II awardees had no prior Phase II awards. They are included in the 85 shown at the top of the left column. For Fast Track, 71% of the winners had no prior awards. BMDO co-investment winners were far more likely to have prior awards. The percentage of BMDO co-investment with no prior Phase II was (85-34)/(175-48) equals 40% which is the average (40%) for all Phase II winners. The expected number with zero, one or two prior awards (122) is the same as in the control group and almost the same as in the study sample (121).

Award of SBIR are not spread uniformly across the country. They tend to cluster in states known for high technology firms, universities, and available venture capital. The table on the next page shows the geographical distribution of the sample compared to the expected distribution.

TABLE A3 Distribution of Samples by States

|

States |

# of Projects Expected from Population |

# of Projects In Control Group |

# of Projects In Study Group |

|

AL |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

AZ |

3 |

4 |

4 |

|

CA |

50 |

50 |

42 |

|

CO |

7 |

10 |

10 |

|

CT |

5 |

9 |

9 |

|

DE |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

FL |

5 |

3 |

3 |

|

GA |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

IL |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

IN |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

KS |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

MA |

31 |

31 |

25 |

|

MD |