Estimates of the Social Returns to Small Business Innovation Research Projects

Albert N. Link* and John T. Scott** University of North Carolina at Greensboro* and Dartmouth College**

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper examines a fundamental rationale for the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program—namely, that government support of private-sector research and development (R&D) through the program is justified because the social benefits associated with the funded research are greater than the social costs, yet without public support, the private costs would be greater than the private benefits. Hence, the socially valuable SBIR R&D would not occur absent the support of the program. Based on interview data collected during case studies of 44 awardees from throughout the United States, we conclude that

-

the funded companies would not have undertaken the R&D without public support because the private return that they perceived they would earn would be less than the minimum accepted rate of return required for private financing of the projects,

-

the estimated lower bound on the social benefits associated with the funded research is greater than the estimated private returns if there were no public support—in terms of the average rates of return on the investments, 84 percent for society compared to 25 percent for the private investors, and

-

the magnitude of the difference between the social and private returns does not vary significantly, on average, between Fast Track and non-Fast Track projects.

INTRODUCTION

The Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982 (P.L. 97-219) required that federal agencies provide special funds to support small business R&D that complemented the funding agency’s mission. This is called the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. Based on the premises, as stated in the Act, that “small business is the principal source of significant innovation in the Nation,” and small businesses are “among the most cost-effective performers of research and development and are particularly capable of developing research and development results into new products,” the Act lists its purposes for, among other things, establishing the SBIR program:

-

to stimulate technological innovation,

-

to use small businesses to meet federal research and development (R&D) needs,

-

to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation, and

-

to increase private-sector commercialized innovations derived from federal R&D.

The Small Business Innovation Research Program Reauthorization Act of 1992 gave reauthorization to the SBIR program because the program has “effectively stimulated the commercialization of technology development through federal research and development, benefiting both the public and private sectors of the Nation.”

In thinking about a program such as SBIR, economists and many policymakers see the generation of positive externalities (i.e., social benefits exceeding private ones) as an important rationale for the program (Lerner, 1999). The purpose of this paper is to examine that underlying premise. Is it in fact the case that the social benefits associated with SBIR-supported projects are greater than the private benefits? Stated alternatively, is there any empirical evidence to suggest that absent the SBIR program the private sector would underinvest in DoD-related technologies?

The remainder of this paper is as follows. In the second section, we present an economic rationale for public–private partnerships and generalize from it to posit a similar rationale for the selection of projects to be funded by SBIR program.1 In the third section, we offer empirical evidence that the social returns from SBIR-supported projects are greater than the private returns, and that without the support of public funding, the socially valuable research would not have been undertaken. In the fourth section, we investigate, in a preliminary fashion, project-specific characteristics associated with the gap between the estimated social and private returns. Then, we offer concluding remarks.

|

1 |

For a more general overview of U.S. public–private partnerships, see Link (1998). |

ECONOMIC RATIONALE FOR PUBLIC–PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

Government’s Role in Innovation

Many date the origin of a U.S. domestic science and technology policy with Vannevar Bush’s Science—the Endless Frontier in 1945. Certainly, Bush’s views about science and the role of universities in sustaining the nation’s science base had a profound impact on the scientific community of his time, as evidenced by the founding soon thereafter of the National Science Foundation in 1950. Bush’s legacy is one of policy focus, emphasizing clearly the importance of basic research in the innovation process. However important Bush’s views, he was not articulate about the economic rationale for government’s role in innovation, much less about addressing issues of public–private partnerships. Bush did articulate an intellectual rationale for public support of basic research and research related to issues of national security, industrial growth, and health and human welfare.

The first official policy statement about domestic technology policy, U.S. Technology Policy, was released by the Executive Office of the President in 1990, coincidentally during the Bush administration. As with any initial policy effort, it was an important general document. However, precedent aside, it failed to articulate a rationale or role for government ’s intervention into the private sector’s innovation processes. Rather, much like Science—the Endless Frontier, it implicitly assumed that government had such a role, and then it set forth a rather general goal (1990, p. 2):

The goal of U.S. technology policy is to make the best use of technology in achieving the national goals of improved quality of life for all Americans, continued economic growth, and national security.

President Clinton took a major step forward in his 1994 Economic Report of the President by articulating first principles about why the government had such a role in innovation and in the overall technological process (p. 191):

Technological progress fuels economic growth . . . . The Administration ’s technology initiatives aim to promote the domestic development and diffusion of growth- and productivity-enhancing technologies. They seek to correct market failures that would otherwise generate too little investment in R&D . . . . The goal of technology policy is not to substitute the government’s judgment for that of private industry in deciding which potential “winners” to back. Rather the point is to correct market failure . . . .

This role for government traces back at least to the writings of Bator (1958). The conceptual importance of identifying market failure for policy is also emphasized by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB, 1996) and summarized by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 1998). However, the Economic Report did not expand on how to correct for market failure, much less discuss appropriate policy mechanisms for doing so.

Risk, Barriers to Technology, and Market Failure

Risk, as well as closely related difficulties regarding the appropriability of returns, create barriers to technology investment and, as a result of these barriers, there may be market failure leading to an underinvestment in or underutilization of technology. Much of the market failure literature focuses on investments in the creation or production of technology (e.g., R&D). Equally relevant, although often overlooked, are investments for the use and application of others’ technology (Tassey, 1997; Link and Scott, 1998a,b).

Risk measures the possibilities that actual outcomes will deviate from expected outcomes, and the shortfall of the private expected outcome from the expected return to society reflects appropriability problems. The technical and market results from technology may be very poor, or perhaps considerably better than the expected outcome. Thus, a firm is justifiably concerned about the risk that its R& D investment may fail, technically or for any other reason. Or, if technically successful, the R&D investment output may not pass the market test for profitability. Further, the firm’s private expected return typically falls short of the social expected return.

The expected outcome is the measure of central tendency for a random variable’s outcome. Risk is sometimes quantified as the variance of the probability distribution for a random variable’s outcome—here, the technical outcome of R&D or the market outcome of the R&D output are the random variables—although other aspects of the probability distribution may affect risk as well. Thus, the contribution to a firm’s overall exposure to risk associated with a particular investment will be different depending on the collection of projects in the portfolio. In that sense, a large firm, with a diversified portfolio of R& D projects, might find a particular project less risky than a small firm with a limited portfolio. Similarly, society faces less risk than the individual firm, large or small, because society has, in essence, a diversified portfolio of R&D projects and that diversification reduces risk that the decision makers in individual firms will consider because of bankruptcy costs or managers’ firm-specific human capital. As risk to society is reduced, overall outcomes become more certain. Further, for each particular technological problem, society cares only that at least one firm solves the technical problems and that at least one is successful in introducing the innovation into the market. The individual firm pursuing the technical solution with R&D and then trying to market the result will of course face a greater risk of technical or market failure.

Facing high risk—both technical and market risk not faced by society—or simply because society has a longer time horizon than the decision makers of individual firms, a private firm discounts future returns at a higher rate than does society. Therefore, the private firm values future returns less and, from society’s perspective, will invest too little in R&D. Put another way, the higher the risk the higher the hurdle rate, or required rate of return, will be for a project. Thus, when

social risk is less than private risk, the private firm will use a hurdle rate that, from society’s perspective, is too high. Socially useful projects accordingly will be rejected. Further, when the firm ’s expected return falls short of society’s expected return, the firm has less future returns to value than society does, and again, underinvestment will result.

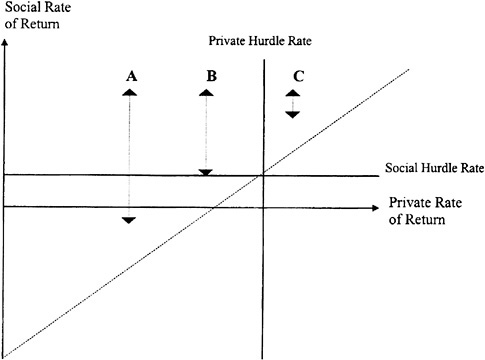

Market failure, resulting from risk and the closely related difficulties of appropriating returns to investments in technology—R&D specifically —will lead to a divergence between private and social benefits. The social rate of return will be greater than the private rate of return; there are, of course, expected, or ex ante, returns. This is illustrated in Figure 1, following Jaffe (1998). The purpose of this simple heuristic device is to characterize private-sector projects with returns not only less than the expected social returns but also less than the private hurdle rate for projects normally undertaken by the firm.

The social rate of return is measured on the vertical axis of Figure 1 along with society’s hurdle rate on investments in R&D. The private rate of return is measured on the horizontal axis along with the private hurdle rate on investments in R&D. A 45-degree line (long dashed line) is imposed on the figure under the assumption that the social rate of return from an R&D investment will at least equal to the private rate of return from that same investment. The three illustrative projects discussed below are labeled as projects A, B, and C.

FIGURE 1 Gap between social and private rates of return to R&D projects.

For project C, the private rate of return exceeds the private hurdle rate, and the social rate of return exceeds the social hurdle rate. The gap (short vertical dashed line) between the social and private rates of return reflects the spillover benefits to society from the private investment. However, the inability of the private sector to appropriate all benefits from its investment is not so great as to prevent the project from being adequately funded by the private firm. In general, then, any R&D project with a private rate of return to the right of the private hurdle rate and on or above the 45-degree line is not a candidate for public support because, even in the presence of spillover benefits, the R&D project will be funded by the private firm.

Consider projects A and B. The gap between social and private returns is larger than in the case of project C; neither project will be adequately funded by the private firm. To address this market failure, the government has two alternative policy mechanisms. It can use a tax policy to address the private underinvestment in R&D or it can rely on public–private partnerships as a direct funding mechanism.

If the private return to project B is less than the private hurdle rate because of the risk and uncertainty associated with R&D in general, then tax policy may be the appropriate policy mechanism to overcome this underinvestment. Risk is inherent in a technology-based market, and there will be certain projects for which the rewards from successful innovation are too low for private investments to be justified. Tax policy, such as the research and experimentation tax credit, may in these situations reduce the private marginal cost of R&D sufficiently to provide an incentive for the project to be undertaken privately. For projects such as B, a tax credit may be sufficient to increase the expected return so that the firm views the post-tax-credit private return to be sufficient for the project to be funded.

However, for projects such as A, a tax credit may be insufficient to increase the expected return so as to induce the private firm to undertake the project. For example, a project expected to yield an innovative product that would be part of a larger system of products, even if technically successful, might not interoperate or be compatible with other emerging products. In such a case, direct funding rather than a tax credit may be the appropriate policy mechanism.

A priori, it is difficult to generalize about the way that any one firm’s underfunded projects will be distributed in the area to the left of the firm’s private hurdle rate. However, some generalizations can be made about the portfolio of private-sector firms’ projects in general. For those R&D projects, like project B, for which the firm will appropriate some returns but for which the overall expected return is slightly too low, a tax credit may be sufficient to increase the expected return to the point that the expected return exceeds the private hurdle rate. Such projects may be of a product or process development nature and are likely to be a part of the firm’s ongoing R&D portfolio of projects. For those R&D projects, like project A, for which the firm has little ability to appropriate returns even if the marginal cost of the project is reduced through an R&D tax

credit, for example, the firm may not respond to such an R&D tax policy but may respond to a direct-funding mechanism. Such projects are likely to be of a generic technology nature, that is, technology from which subsequent market applications are derived and that enable downstream applied R&D to be undertaken successfully. Generic technology and the associated research process represent the organization of knowledge into the conceptual form of an eventual application and the laboratory testing of the concept. Generic technology draws on the science base but, unlike scientific knowledge, it has a functional focus.

Thus, the economic rationale for public-private partnerships is that such partnerships represent one direct-funding R&D policy appropriate to overcome market failure and they are more likely to be necessary, compared to fiscal tax incentives, when the R&D is generic in character.

Drawing upon the arguments set forth earlier, we maintain that a candidate project for SBIR awards is one like project A in Figure 1. That is, given that the proposed research aligns with the technology mission of DoD, SBIR should fund such projects for which there is a significant potential social benefit but also that are characterized by substantial downside risk such that the firm’s expected private return is well below its private hurdle rate.

Case information reported by Link (1999) and Scott (1999) confirms for a small sample of SBIR-supported projects that not only are the firms’ private returns less than their private hurdle rate but also that outside investors are unwilling to fully sponsor the research because of both technical and market risk. Hence, at the outset of an SBIR project, not only is a firm’s private hurdle rate not expected to be met, neither is the required return for a third party. The case information provided by Link (1999) and Scott (1999) clearly indicates that there is a market failure.

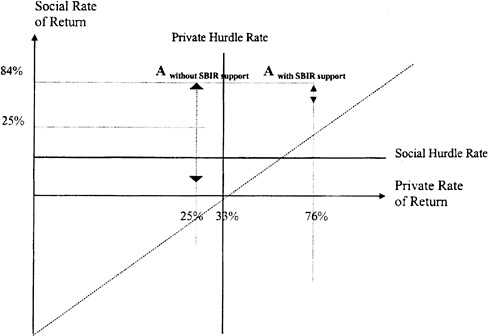

PRELIMINARY ESTIMATES OF SOCIAL RETURNS

As part of this study, 44 SBIR award recipients were interviewed. Each company was interviewed toward the end of its Phase II award period. From each, we collected information that allowed us to calculate a lower-bound for the prospective expected social rate of return associated with each project and to compare that prospective expected social return to both the expected private return to the firm had it pursued the project in the absence of SBIR support and the expected private return expected by the firm with its SBIR support. Our analysis clearly indicates that the SBIR is funding projects like project A in Figure 1 and, given such funding, the project has become similar to project C.

Sample of Projects

The sample of projects studied is not intended to be representative of all projects funded by the SBIR program. Rather, because of the timing constraints associated with this study, the sample of projects was selected as follows:

TABLE 1 Characteristics of the Sample (N = 44)

|

Characteristic |

Number |

|

Region |

|

|

Northeast |

17 |

|

Southeast |

13 |

|

West |

14 |

|

Funding Mechanism |

|

|

Fast Track |

14 |

|

Non-Fast Track |

30 |

Independent of this analysis, Link (1999) examined SBIR projects in the southeastern states and Scott (1999) examined SBIR projects in the northeastern states. Each of those two samples was selected for the purpose of comparing Fast Track projects to non-Fast Track projects in each region. In addition to those projects, other projects were identified on the basis of early responses to a broad-based mail survey conducted for the DoD by Peter Cahill, as discussed by Audretsch et al. (1999).

Given the practicality criterion that was imposed on the selection of the sample of 44 projects, no generalizations should be made about SBIR projects as a whole. However, the methodology that we implemented is sufficiently rich to be applied to other samples.

Table 1 describes selected characteristics of the sample of projects examined here.

Analytical Framework for Estimating Social Returns

Table 2 lists the variables required for implementation of our model. As noted in the table, data on selected variables were independently available from DoD project files, but all such information also was verified during the interview process and corrected when discrepancies were found.

Phase I and Phase II values for project duration (d), total cost (C), and SBIR funding (A) were combined into one value to cover both Phase I and Phase II of the project. That is, each project is viewed from the time that Phase I began, and expectations from that point forward are estimated. It is at that point in time that the market failure issues discussed earlier are especially relevant. The variables z and F refer to the additional period of time beyond the expected completion of Phase II until the research would be commercialized and the additional cost required during that period.

The variable v, the proportion of value appropriated, deserves some explanation. Firms cannot reasonably expect to appropriate all of the value created by

TABLE 2 Variables for Calculation of the Prospective Expected Social Rate of Return

|

Variable |

Definition |

Source |

|

d |

Duration of SBIR project |

DoD files, verified and updated as necessary during interviews |

|

C |

Total cost of the SBIR project |

DoD files, verified and updated as necessary during interviews |

|

A |

SBIR funding |

DoD files, verified and updated as necessary during interviews |

|

r |

Private hurdle rate |

Interview |

|

z |

Duration of the extra period of development beyond Phase II |

Interview |

|

F |

Additional cost for the extra period of development |

Interview |

|

T |

Life of the commercialized technology |

Interview |

|

v |

Proportion of value appropriated |

Interview |

|

L |

Lower bound for expected annual private return to the SBIR firm |

Derived |

|

U |

Upper bound for expected annual private return to the SBIR firm |

Derived |

their research and subsequent innovations. First, the innovations will generate consumer surplus that no firm will appropriate, but that society will value. We ignore consumer surplus in our calculations of the prospective expected social returns, thus motivating our claim that our estimates are lower-bound estimates. Second, some of the profits generated by the innovations will be captured by other firms. Larger firms, for example, will observe the innovation and will successfully introduce imitations. As part of the interview process, each respondent was asked to estimate the proportion of the return generated by its anticipated innovation that it expected to capture. Then, in an extended conversation, other possible applications of the technology developed during the SBIR project were explored. Each respondent was asked to estimate the multiplier to get from the profit stream generated by the immediate applications of the SBIR projects to the stream of profits generated in the broader application markets that could reasonably be anticipated. Finally, each respondent estimated the proportion of the returns in those broader markets that it anticipated capturing. From these extended discussions, we estimated the proportion of value appropriated by the innovating SBIR awardee.

The lower bound for the annual private return to an SBIR-sponsored project is found by solving Eq. (1) for L, because that is the value that the private firm earns just to meet its private hurdle rate, or its required rate of return, on the portion of the total investment that the firm must finance. The firm would not

invest in the SBIR project on its own unless it expected at least L for the annual private return on its investment.2

(1)

To determine the upper bound for the annual private return, U, Eq. (2) is solved for U. Any expected annual return greater than U would imply that the expected rate of return earned by the private firm would be greater than its hurdle rate in the absence of SBIR support, and therefore SBIR support would not be required for the project.

(2)

Our estimate of the average expected annual private return to the firm is [(L + U)/2]. If the average expected annual private return is [(L + U)/2)] and the portion of producer surplus that is appropriable, v, is known, then the total producer surplus equals [(L + U)/2v] and hence this value is a lower bound for the expected annual social return. Again, it is a lower bound because consumer surplus has not been measured.

The expected private rate of return without SBIR support is the solution to i in Eq. (3), given solution values for L and U from Eqs. (1) and (2). The solution

|

2 |

Equation (1) consists of three general terms. Each term represents the present value for a particular flow that is realized over a particular time period. The first term in the equation represents the present value of the negative cash flows that result to the firm from the cost of conducting the project, C − A, from its start to its expected completion, t = 0 to d. The second term is the present value of the future negative cash flows from the additional cost, F, of taking the generic technology from the project, at t = d, and commercializing it, at t = d + z. Finally, the third term is the present value of the expected net cash flows from the project, L, after it has been commercialized, at t = d + z, over its estimated life, to t = d + z + T. Note that the discount rate in Eq. (1) is the firm’s hurdle rate, r. Therefore, the value for L that solves Eq. (1) is the value for which the private firm just earns its hurdle rate of return on the portion of the total investment that it must finance. The firm would not invest in the project unless it expected at least L for the average annual private return, so that its hurdle rate would be exactly met. Thus, L is a lower-bound estimate. |

value of i in Eq. (3) represents the rate of return that just equates the present value of the expected annual private return to the firm to the present value of research and postresearch commercialization costs to the firm in the absence of SBIR funding.

(3)

Finally, the lower bound on the social rate of return is found by solving Eq. (4) for i, given values for the other variables.3

(4)

Equations (1) through (4) were estimated for each of the 44 SBIR-sponsored projects. Mean values of the two resulting important rates of return, averaged across the 44 projects, are shown in Table 3. There are two important points to be seen in Table 3: First, the average of the expected private rate of return in the absence of SBIR support is 25 percent, clearly less than the average self-reported private hurdle rate of 33 percent (see Table 4). Thus, in the absence of SBIR support, this sample of firms would not have undertaken this research and, in fact, they expressed this fact explicitly during the interviews. Second, the expected social rate of return (lower bound) associated with SBIR’s funding of the these projects is at least 84 percent, and hence the projects are expected to be socially valuable.

We cannot conclude that a social rate of return of at least 84 percent is good or bad, or better or worse than expected. Those are nonaxiomatic conclusions. However, we can compare our estimate of the lower bound of the social rate of return to the opportunity cost of public funds. Following the guidelines set forth by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget to use a real discount of 7 percent for constant-dollar benefit-to-cost analyses of proposed investments and regulations, we find that, clearly, a nominal social rate of return of 84 percent is above that rate and thus is socially worthwhile.4

We also can calculate the expected private rate of return with SBIR support for each of the 44 projects as the solution to i in Eq. (5), given the values of d, C, A, z, F, and T and the derived values of L and U from Eqs. (1) and (2) using those values:

|

3 |

Note that Eq. (4) is identical to Eq. (3) with the exception that the average expected annual private return, [(L + U)/2], is replaced with the lower bound for the average expected annual social return, [(L + U)/2v]. |

|

4 |

Link and Scott (1998b) discuss the use of this guideline for National Institute of Standards and Technology economic impact assessments. |

TABLE 3 Rates of return for Average Project (N = 44)

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

iprivate = 0.25 |

Expected private rate of return without SBIR funding |

|

isocial = 0.84 |

Lower bound for expected social rate of return |

(5)

The estimated private rate of return with SBIR support averages 76 percent for the 44 cases; this value is noticeably above the average private hurdle rate of 33 percent. However, there is no way for SBIR to have calculated the optimal level of funding for these 44 projects, or for any projects, unless, as part of the Phase I application, all relevant data, including hurdle rates, could have been assessed. In the absence of such information, which in practice would be difficult to obtain because of, if nothing else, self-serving reporting by proposers, the funding scheme that SBIR has implemented may be as close to optimal as possible.5

Figure 2 summarizes our estimated values for the average SBIR-sponsored project. Based on the sample of 44 projects, the average gap between the lower-bound social rate of return and the estimated private rate of return without SBIR funding support is 59 percent.

TABLE 4 Descriptive Statistics on Variables (N = 44)

|

Variable |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

d |

2.68 years |

0.36 |

|

C |

$1,027,199 |

461,901 |

|

A |

$782,000 |

127,371 |

|

r |

0.33 |

0.08 |

|

z |

1.30 years |

1.07 |

|

F |

$1,377,341 |

2,972,266 |

|

T |

10.56 years |

7.23 |

|

v |

0.16 |

0.16 |

|

L |

$902,738 |

1,228,850 |

|

U |

$1,893,001 |

1,733,581 |

|

5 |

Scott (1998) has proposed using a bidding mechanism that would result in the SBIR funding being just sufficient to ensure that the private participants earn just a normal rate of return. The proposal is a novel one, but it is as yet untried. Successful implementation would require additional development to make it practicable. |

FIGURE 2 Gap between social and private rates of return to the average SBIR project (N = 44).

INTERPROJECT DIFFERENCES IN THE GAP BETWEEN SOCIAL AND PRIVATE RETURNS

On the basis of the estimation of the preceding equations, we calculated for each project the gap between the lower-bound social rate of return and the private rate of return without SBIR funding support. In an exploratory fashion, we considered interproject differences in this spillover gap as a function of the geographic region of the company conducting the research, and the SBIR funding mechanism (Fast Track versus non-Fast Track).

Consider the following fixed-effects model:

(6)

where Gap represents the difference between the lower-bound social rate of return and the private rate of return; FT is a binary variable equaling 1 if the project was funded as a Fast Track project and 0 otherwise; NE is a binary variable equaling 1 if the company conducting the research is located in a northeastern state, and 0 otherwise; and W is a binary variable equaling 1 if the company conducting the research is located in the west (California in fact), and 0 otherwise. The least-squares results are reported in Table 5.

TABLE 5 Regression Results from Eq. (6) (N = 44)

|

Dependent Variable Gap |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

t statistic |

p > |t| |

|

|

constant |

0.811 |

10.2 |

0.000 |

|

|

FT |

0.0752 |

0.86 |

0.395 |

|

|

NE |

−0.475 |

−4.78 |

0.000 |

|

|

W |

−0.168 |

−1.62 |

0.112 |

|

|

R2 = 0.38 |

||||

|

F level = 8.19, p > F = 0.0002 |

||||

|

Expected Gap as Predicted by the Model |

||||

|

Variable |

Fast Track |

Non-Fast Track |

||

|

NE |

∃0 + ∃1 + ∃2 = 0.411 |

∃0 + ∃2 = 0.336 |

||

|

SE |

∃0 + ∃1 = 0.886 |

∃0 = 0.811 |

||

|

W |

∃0 + ∃1 + ∃3 = 0.718 |

∃0 + ∃3 = 0.643 |

||

What is clear from the estimation of Eq. (6), after controlling for region, is that there is not a statistically significant difference between the gap of Fast Track and non-Fast Track projects, meaning that in this sample the expected spillover benefits from Fast Track projects are equal to those of non-Fast Track projects. Shown in Table 6 are the mean values of the gap by region, and clearly there are regional differences.

Although there is not a statistical difference in the gap between Fast Track and non-Fast Track projects, there are differences, as would be expected, between the component measures of Gap—the lower-bound estimate of the social rate of return and the estimate of the private rate of return without SBIR funding support. A priori, we expected higher prospective estimated social rates of return among Fast Track projects because these are the projects that have attracted outside investors at an early state in the research in anticipation that they were projects that were closer to commercialization. This same reasoning implies a priori that these companies also would have a greater private rate of return without SBIR funding support. As shown in Table 7, these differences are born out in the data.

TABLE 6 Descriptive statistics related to the gap variable (N = 44)

|

Variable Gap |

Mean (%) |

|

Northeast (n = 17) |

36 |

|

Southeast (n = 13) |

83 |

|

West (n = 14) |

66 |

TABLE 7 Mean Values Related to the Components of the Gap Variable (N = 44)

|

Variable |

Fast Track (n = 14) |

Non-Fast Track (n = 30) |

|

Gap |

0.63 |

0.58 |

|

Lower-bound social rate of return |

0.93 |

0.80 |

|

Private rate of return without SBIR funding |

0.30 |

0.22 |

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Two points need to be emphasized as caveats to our conclusion that, as measured by our sample of 44 projects, SBIR is funding socially desirable projects. First, the social rates of return estimated for the SBIR projects are very conservative, lower-bound estimates because they do not include consumer surplus in the benefit stream. Second, some might be skeptical about the SBIR awardees’ earnest belief that without SBIR funding the projects would not have been undertaken or at least would not have been undertaken to the same extent or with the same speed. With the SBIR program in place, the pursuit of SBIR funding probably would be a path of least resistance. However, if the research would have occurred without the public funding, the estimated upper bound and hence the average of the upper and lower bounds for the expected private returns would be too low, and the actual lower bounds for the social rates of return would be even higher than we have estimated. Further, the gap would remain, although that would not in itself necessarily justify the public funding of the projects.

REFERENCES

Audretsch, David B., Albert N. Link, and John T. Scott. 1999. “Analysis of the National Academy of Sciences’ Survey of Small Business Innovation Research Awardees,” this volume.

Baron, Jonathan. 1998. DoD SBIR/STTR Program Manager. Comments at the Methodology Workshop on the Assessment of Current SBIR Program Initiatives, Washington, D.C., October.

Bator, Francis. 1958. “The anatomy of market failure,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 351–379.

Bush, Vannevar. 1946. Science—the Endless Frontier. Republished in 1960 by U.S. National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Clinton, William Jefferson. 1994. Economic Report of the President. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Jaffe, Adam B. 1998. “The importance of ‘spillovers’ in the policy mission of the Advanced Technology Program,” Journal of Technology Transfer (Summer).

Lerner, Joshua. 1999. “Public Venture Capital: Rationale and Evaluations, in National Academy of Sciences,” The Small Business Innovation Research Program: Challenges and Opportunities . Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, pp. 115-128.

Link, Albert N. 1998. Public/Private Partnerships as a Tool to Support Industrial R&D: Experiences in the United States, Final report prepared for the Working Group on Technology and Innovation Policy, Division of Science and Technology, Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, January.

Link, Albert N. 1999. “An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Fast Track Program in Southeastern States,” this volume.

Link, Albert N., and John T. Scott. 1998a. “Assessing the infrastructural needs of a technology-based service sector: A new approach to technology policy planning,” STI Review 22:171–207.

Link, Albert N., and John T. Scott. 1998b. Public Accountability: Evaluating Technology-Based Institutions. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). 1998. Technology, Productivity and Job Creation: Toward Best Policy Practice . Paris: OECD.

Office of the President. 1990. U.S. Technology Policy. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

OMB (Office of Management and Budget). 1996. Economic analysis of federal regulations under Executive Order 12866 . Mimeo.

Scott, John T. 1998. financing and leveraging public/private partnerships: The hurdle-lowering auction,” STI Review 23:67–84.

Scott, John T. 1999. “An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program in New England: Fast-Track Compared with non-Fast Track Projects,” this volume.

Tassey, Gregory. 1997. The Economics of R&D Policy. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.