12

Informed Consent for the Collection of Biological Samples in Household Surveys

Jeffrey R.Botkin

The National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) estimates that there are over 282 million human biologic specimens being stored in the United States, and that this number is growing by 20 million samples per year (NBAC, 1999). These tissue samples have been collected by hospitals in the course of routine clinical care, investigators, public health agencies, health care companies, and nonprofit organizations. While many of these collections have existed for generations, controversy has arisen in the past decade over the appropriate use of these resources for research. This debate has its roots in several developments: (1) contemporary genetic technology permits a detailed analysis of small tissue samples; (2) a wide variety of mutations have been identified that are associated with serious health problems; (3) there is substantial concern in medicine and the general public over genetic discrimination in insurance and employment; and (4) many samples have been collected without informed consent for their use in research.

To a large extent, the most heated controversy has focused on the use of existing samples collected over years or decades for new genetic research projects. Large repositories that are linked with demographic and health information about the tissue sources can be a valuable tool for research (Wallace, 1997). However, if the analysis of stored tissues poses some risk to the tissue source, and adequate informed consent has not been obtained, then use of the specimens may not be appropriate. Recontacting tissue sources for consent may be prohibitive in terms of time, effort, and expense, thereby rendering the repository useless for research purposes. This is

the situation in which the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) found itself following the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III study (Steinberg et al., 1998). Through this extensive national project, the CDC collected information on approximately 40,000 individuals, blood and urine samples on 19,500, and developed 8,500 permanent cell lines. Unfortunately, the detailed consent from participants did not explicitly cover genetic research on the specimens. Thus a crisis arose over whether the samples could be used for genetic research without recontacting participants for their specific approval.

To address these concerns, a conference and working group were convened in 1994. The CDC and the National Human Genome Research Institute sponsored the effort that resulted in a statement of guidelines published in 1995 (Clayton et al., 1995). This statement proved to be somewhat controversial in its own right, fostering broad discussion from a variety of perspectives (American Society of Human Genetics, 1996; American College of Medical Genetics, 1995; Grizzle et al., 1999; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1997; Office for Protection from Research Risks, 1997). The use of stored tissues in research became one of the first issues to be addressed by the NBAC in its 1999 report titled “Research Involving Human Biologic Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance.” Similar debates have arisen in recent years over the use of DNA databanks in criminal law (McEwen, 1998) and in the military (Kipnis, 1998).

This brief sketch of the recent controversies over stored tissue samples illustrates two points. First, the current discussion of the collection of biologic samples in household surveys occurs within a charged atmosphere. Given the appropriate, renewed scrutiny being applied to human subject protections in research, a cursory approach to consent issues may impair or destroy the value of specimens obtained in household surveys. Second, the debate over informed consent for tissue storage and research use is sufficiently mature to enable the development of prudent consent procedures that can maximize the utility of specimens while respecting the prerogative of subjects to control their contributions to research and the risks associated with research participation. For the purposes of this chapter, we need not address the controversy over the use of existing specimens. The following discussion will focus on consent for the prospective collection of specimens in household surveys.

INFORMED CONSENT

The purpose of informed consent is severalfold. In the clinical environment, the primary purpose is to permit patients to make informed choices about appropriate options for care. To a significant extent, the

concept of informed consent did not arise within medicine, but rather was promulgated through the courts in response to cases in which patients had adverse consequences following procedures that had not been fully discussed. The emergence of informed consent parallels the consumer rights movement in society more broadly and the rejection of paternalism in medicine more specifically. The corollary to the protection of a patient’s prerogative to make informed decisions about his or her own care is the legal protection that informed consent confers on care providers. While malpractice suits involving inadequate informed consent are relatively rare, a full discussion of medical options and clear documentation of these discussions protects providers from successful suits (based on inadequate consent) if a choice leads to a poor outcome.

Unfortunately, the legal dimensions of informed consent tend to overshadow the fundamental importance of this doctrine in medicine. The basic principle is that patients should be active participants in deciding their course of care. The central dialogue in medicine, that is, discussing what is wrong with the patient, what options are available, and what course should be followed, constitutes the process of informed consent. The signing of the consent form, when appropriate or necessary, documents what was discussed but should not be misconstrued as informed consent itself.

In therapeutic research, informed consent serves a similar role as that in clinical care, with the obvious difference that the experimental option remains to be fully evaluated. Offering a potentially ineffective or harmful option requires more thorough consent procedures than those in clinical medicine, including more detailed disclosures, consent forms, and prior review of protocols and forms by an institutional review board (IRB).

Nontherapeutic research is the most complex from an ethical perspective. The most egregious examples of abuse in U.S. biomedical research have involved nontherapeutic research projects, including the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital, Willowbrook, and the human radiation experiments (Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments, 1995). It is notable that several of the most notorious of these experiments (Tuskegee and the radiation experiments) involved active participation by federal agencies. Public concern following the revelation of some of these projects led to the federal regulations currently in place to govern the conduct of research (Caplan, 1992).

By definition, nontherapeutic research offers no prospect of direct benefit to the subject. The benefit, if any, may accrue to the subject in the future, through a better understanding of the treatment or prevention of disease, or the benefit may accrue to others in society. When properly conducted, nontherapeutic research appeals to the altruism of individuals

to place themselves at some risk, largely for the uncertain benefit of others. When not properly conducted, nontherapeutic research simply uses poorly informed or unwitting subjects as tools for research ends. Detailed consent for participation in research is at the core of the ethical justification for involving subjects in nonbeneficial research. The other essential pillar on which the ethical justification of research rests is peer review.

THE COMMON RULE

A household survey with the collection of biologic specimens constitutes nontherapeutic research and, if conducted under the auspices of the federal government, is subject to federal regulations under Title 45, Part 46 of the Code of Federal Regulations (Department of Health and Human Services, 1991). The regulations exempt research on existing databases, records, or specimens if these resources are publicly available or if the resource has been stripped of all individual identifiers. Any prospective collection of individual information and tissue samples would not be exempt from federal regulations. However, the regulations permit research without informed consent in specific circumstances, subject to IRB approval:

-

the research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects;

-

the waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects;

-

the research could not practically be carried out without the waiver or alteration; and

-

whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.

These criteria are unlikely to be met by a household survey involving biologic specimens.

The definition of minimal risk provided by the regulations is relatively vague and is intended to be interpreted by IRBs in the context of specific proposals. The definition states:

Minimal risk means that the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests.

We can imagine a household survey with specimen collection that would meet several of the requirements for waiver of informed consent. A survey to include limited demographic data and a cheek swab for ABO/Rh blood type would meet the standard of minimal risk and waiver of consent would not adversely affect the rights or welfare of the subject. However, it would be difficult to argue that consent was not practical in the

context of a household survey. At a minimum, subjects have the right to know the purpose of the research and what was going to be done with the data and the biologic specimen. Of course, most useful household surveys will involve extensive data collection, including sensitive information such as health status, and collection of specimens for a variety of analyses. Therefore, it is unlikely that household surveys with specimen collection would qualify for waiver of consent under any circumstances.

The federal regulations require the following elements to be included in the consent process:

-

a statement that the study involves research, and explanation of the purposes of the research and the expected duration of the subject’s participation;

-

a description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject;

-

a description of any benefits to the subject or to others which may reasonably be expected from the research;

-

a disclosure of the appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject;

-

a statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained;

-

for research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation and an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available if injury occurs;

-

an explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions; and

-

a statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled.

Some of these elements, such as point 4, have limited relevance to household surveys with the collection of samples. Further, there are additional considerations relevant to the collection of specimens for a repository, that is, when specimens are collected for use in future, unspecified research projects. These issues will be discussed in detail below.

The extent of the information provided in the consent process is determined largely by the magnitude of the risks, discomforts, and inconveniences involved in the research. This is not to say that these burdens are the only consideration. Individuals have prerogatives to control information about themselves even when there is no risk involved. More specifically, privacy rights are not contingent solely on the presence of risk (Allen, 1997). Conversely, privacy is not absolute, and a variety of

public health and public policy activities involve the collection and sharing of personal information. Personal financial information and data on our purchasing behaviors are often widely shared in the private sector. In addition, as noted above, research projects need not always obtain subject consent to be included if certain criteria are met. But public sensitivity toward privacy issues is growing and, at least in the public sector, there must be clear justification for any threats to individual privacy. The point here is that in this context detailed consent is appropriate, not necessarily because there are profound risks involved in this research, but because potential subjects have the right to exert substantial control over information about themselves and their families.

RISKS OF RESEARCH ON TISSUE SAMPLES

The nature of the informed consent will be strongly influenced both by the magnitude of the risks involved and by the perceived magnitude of the risks by potential subjects. In recent years, there has been extensive discussion of genetic privacy issues, including numerous newspaper and magazine articles directed to the general public. This discussion has raised widespread concern in the United States over breaches in privacy or confidentiality leading to discrimination in insurance and employment secondary to genetic testing (Fuller et al., 1999). Some of these risks may have been overstated; nevertheless, they are an important part of discussions and disclosures to potential research subjects.

Of course, not all testing of tissue samples involves genetic testing. Genetics has received the lion’s share of attention due to the perception that our DNA constitutes a “future diary,” readable by those with new technical capabilities (Annas, 1993; Annas et al., 1995). The primary fear is that genetic testing may reveal a high risk of a specific future illness. Learning this predictive information, particularly if there are no effective interventions to prevent or treat the disease, might cause personal distress, social stigma, and discrimination. In addition, genetic testing may reveal family information, including the mutation status of a parent, or revelations like misattributed paternity. Third, the concern over genetic information is heightened by the history of abuse of genetic information during the eugenics era and under German National Socialism, but also more recently with the sickle cell screening program in the United States during the 1970s. This claim that genetic tests deserve special scrutiny has been termed “genetic exceptionalism” (Murray, 1997).

Several authors have taken the position that genetic testing is not unique or fundamentally different from other testing modalities (see, e.g., Murray, 1997). It can be argued that the problematic nature of tests is not governed by whether they are genetic or not, but by whether the test is

strongly predictive of future illness and whether the information has implications for others such as family members. HIV testing is not genetic in nature, for example, but shares many of the problematic aspects of genetic testing. Conversely, most genetic tests should not raise particular concerns because most tests are not highly predictive of future illness, nor do they have serious implications for other individuals. Genetic tests may have these problematic characteristics more often than nongenetic tests, but it is the attributes of the specific tests that are important to informed consent, not the fact that the tests are genetic.1

Further, one aspect that nongenetic tests have that many genetic tests do not is the ability to detect current disease. Genetic tests (other than perhaps tumor markers) are not generally useful for detecting silent or presymptomatic disease. For example, inclusion of nongenetic tests such as liver or renal function tests on a household survey would confer the ability to detect current liver or kidney dysfunction—problems about which the subject may not be aware. Learning this unanticipated information may constitute a benefit in otherwise nontherapeutic survey research, assuming the results are returned to subjects and there are effective interventions to improve health. However, this diagnostic information also could produce distress, stigma, and discrimination. These potential risks and benefits would need to be addressed in developing the research protocol and in the consent process. Therefore, in this context, the attributes of the specific tests to be included on a household survey must be individually evaluated, and considerations about consent should not be overly influenced by the technology used to run the tests.

One unique aspect of genetic tests that does deserve additional scrutiny is the potential of genetic information to stigmatize entire communities. Perceived genetic differences between racial and ethnic groups have been a powerful source of discrimination and even genocide in the past. The use of genetic information to characterize (or mischaracterize) whole communities is a rational fear. Genetic research to evaluate genes associated with alcoholism in the Native American population, or for criminality in the African-American population would be viewed with great suspicion and hostility in these communities (Coombs, 1999). Clearly any finding that purported to demonstrate a genetic basis for a stereotype of a racial or ethnic group could be harmful to all those who share the racial or ethnic identity, whether or not they were involved in the research. In addition, different cultures place different values on tissue samples, decision-making, and health research that have significant implications for how specimens might be obtained and handled (Freedman 1998; Foster et

al., 1998). For these reasons, there is legitimate concern over some kinds of genetic research in specific ethnic and racial groups, even when individual specimens have been rendered anonymous (Clayton, 1995). This concern has led to suggestions that subjects be afforded choice over the use of their tissues even when the tissues are unlinked to individual identities but retain demographic links, and that protocols be subject to review and approval by communities in addition to individual subjects (Freedman, 1998). This issue is discussed in greater detail by Durfy (2000) in this volume.

TYPES OF REPOSITORIES AND SAMPLES

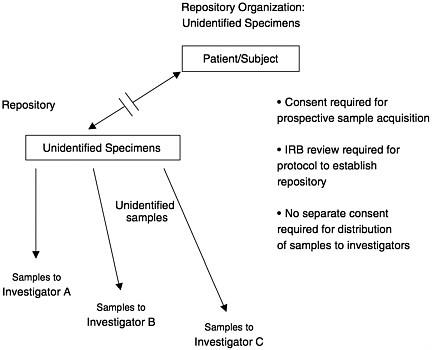

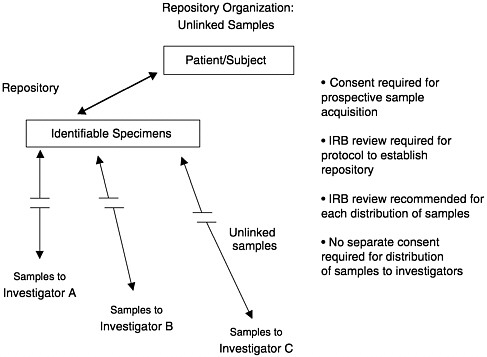

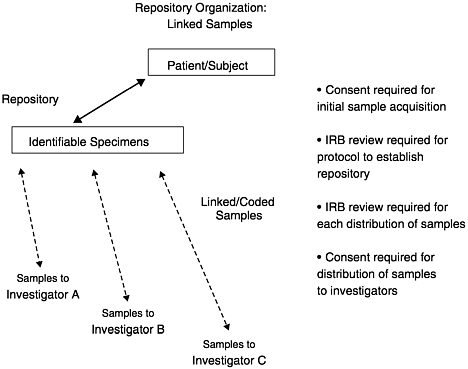

A key strategy to reduce the risk of research with medical data and tissues is to remove individual identifiers from the data and/or samples. A useful framework and terminology has been provided by the NBAC (1999) in their discussion of this strategy. First, there is a distinction between how the specimens are handled in a repository and how individual samples might be used or distributed from the repository. Using the NBAC terminology, specimens are retained in repositories, while samples from the specimens are distributed to investigators from the repository.

An initial decision with any proposal to conduct a household survey with tissue acquisition will be about the storage and management of the specimens. A repository refers to a tissue bank that is established as a source of samples for future, currently unspecified research. If the purpose of the project is to run only a predetermined battery of tests on the tissue, then a repository would not be necessary. Presumably, residual tissues would be destroyed after the completion of the test battery. From the perspective of subject consent, this approach has the advantage of enabling a full discussion of the scope of the research and its risks and benefits. However, the obvious disadvantage is that a potentially large specimen collection is not available for future research using new ideas and technologies as they develop. For this reason, a large household survey would maximize the utility of the specimens by creating a repository that could be utilized by future investigators. From the perspective of subject consent, this approach becomes considerably more complex since the ultimate use of the samples is presently unknown.

Specimens in a repository can be either identified or unidentified. In the terminology being used in this domain, unidentified samples are those that cannot be traced back to the specimen source by anyone. Therefore the word unidentified is equivalent to anonymous. Identifying information obviously includes personal information such as names, addresses, social security numbers, but it also may include a pattern of information that is sufficiently unusual to identify an individual. For example, to label

a specimen with information that the source is an elderly African-American man with scleroderma in North Dakota might make it traceable to a single individual in the survey database. Therefore, labeling in a repository with unidentified specimens must be sufficiently complete to make the specimens useful, but not so detailed that some sources can be identified.

An advantage to developing a repository with unidentified specimens is that the specimens are no longer considered human subjects under federal regulations (Department of Health and Human Services, 1991). Human subject means “a living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research obtains (1) data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or (2) identifiable private information.” Subsequent use of unidentified specimens would not require informed consent from the subjects or IRB review. The disadvantage of a repository with unidentified specimens is the limited data on the tissue sources that can be used in the analysis of the samples.

NBAC has defined several different types of research samples, depending on the degree to which they are linked with the tissue source. Unidentified samples are those from unidentified specimens in a repository. Unlinked samples are those that have been “anonymized,” meaning that the samples came from identifiable specimens but have been stripped of all identifying information. Again, this means that no one can trace the sample back to the source. Coded samples, or linked samples, are labeled with a code that permits identification of the tissue source. In many circumstances, only the repository or a designated third party will have access to the database containing the link between the code and the individual identifiers. In this situation, investigators using linked samples cannot identify the source of the tissue, although the repository (or a third party) would retain this ability. Because the tissues remain linked to their sources under this option, use of the samples remains under federal regulation and must be approved by an IRB.

The National Institute of Health’s Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR, which is now called the Office for Human Research Protections) has explicitly recommended that repositories not release identifiable samples. In its 1997 guidelines on stored tissues, the OPRR (1997) stated: “[An] IRB should set the conditions under which data and specimens may be accepted and shared. OPRR strongly recommends that one such condition stipulate that recipient-investigators not be provided access to the identities of donor-subjects or to information through which the identities of donor-subjects may readily be ascertained.” The advantage of this approach is that it permits use of samples for a variety of projects in the indefinite future without the need to return to tissue sources for consent for each project—as long as the projects are consistent with the original consent provided by the subjects.

A complexity of using linked samples is that information that is clinically relevant to the tissue source may be generated in research projects. As long as the tissue source is identifiable, this creates the dilemma over whether to notify the subject or his or her family members about the results. These issues will be discussed in more detail below. Finally, identified samples are those that retain individual identifiers such as names or medical record numbers.

In summary, specimens can be stored in an identifiable or unidentifiable state. Identifiable specimens in a repository can be distributed to investigators in an unlinked, coded, or identifiable state. There is an inherent tension between the amount of subject information linked with the sample and the stringency of the consent requirements and security measures necessary. The scientific value of the samples is enhanced with more information about the subjects available, but the threats to subject privacy and confidentiality are increased as well. Depending on the nature of the project, a common balance between these competing interests is struck by maintaining a repository with identified specimens and by establishing procedures for distributing unlinked or coded samples to qualified investigators subject to IRB review. Figures 12–1, 12–2, and 12–3 illustrate these options.

FIGURE 12–1 Repository organization: Unidentified specimens.

FIGURE 12–2 Repository organization: Unlinked samples.

ELEMENTS OF INFORMED CONSENT

Investigators and an IRB have final authority over the content of informed consent discussions and documents. The following issues will be presented as points to consider in developing a consent process for a household survey involving biological samples. An assumption in developing these points is that specimens will be identifiable in a repository. As discussed above, creation of a repository with unidentified specimens reduces the complexity of creating the repository and accessing the specimens, but also reduces the scientific value of the resource. Further, many of the points will be developed here with the assumption that samples will be distributed from the repository for research projects that will be conceived in the future. Consistent with the guidelines developed by the NBAC (1999), the OPRR (1997), the NIH/CDC Working Group (Clayton et al., 1995), and the College of American Pathologists Ad Hoc Committee on Stored Tissue (Grizzle et al., 1999), each application to use identifiable specimens in a repository requires separate IRB review.

FIGURE 12–3 Repository organization: Linked samples.

Purpose of the Survey and the Biological Samples

This section is largely self-explanatory, although it is remarkable how often a simple description of the purpose of the project is overlooked. Many people will have a very limited understanding of the potential value of this work, so it may be helpful to illustrate the goals of the project with a brief example. It also will be important to explain to potential subjects why they have been asked to participate. Particularly in the context of a household survey (that is, outside a health care environment), it may be important to describe how individuals were selected, perhaps with reassurances that invitations are based on chance or some broad demographic factor, rather than on any knowledge of an individual’s health status by the sponsoring agency.

What Is Expected of Participants?

A brief description of the expectations and responsibilities of the subjects is important. Questions to be addressed might include: What kinds

of questions will be asked? How much time will the survey take? Will subjects need to collect information on other family members? Will subjects be recontacted in the future for additional information or tissue specimens? In addition, a brief description of the method used to collect the biological sample will be important.

The Nature of the Database and Repository

This discussion would include the key information on how individual data will be stored and accessed. Consistent with the recommendations of the OPRR (1997), the following issues should be considered for discussion:

-

What will happen to the information and specimens provided by the subject?

-

Will the data and specimens be used for research only by investigators currently affiliated with the survey, or will investigators from other institutions be afforded access to samples in the future?

-

What kinds of research will be done with the data and samples?

-

Will data and specimens be coded or individually identifiable, or will individual identifiers be permanently removed from data and/or specimens?

-

If specimens are identifiable, will investigators from other institutions have access to personally identifiable information or samples?

-

How long will specimens be retained? If specimens are to be retained and used indefinitely, this should be communicated to potential subjects. More specifically, subjects should be informed if their specimens will continue to be used after their death.

A clear and concise discussion on these points, when relevant, will be essential for potential subjects to understand the following information and their choices as part of the project.

Communicating Results of the Research

When and how to return research results to subjects remains somewhat controversial. In some circumstances, research protocols use validated tests, the results of which may be clinically valuable for the subject (such as cholesterol measurements or renal function tests). Unless specimens are unidentifiable, it usually is appropriate to return these kinds of results to subjects. Conveying test results is a complex task and is best conducted in a therapeutic relationship where additional evaluation and follow-up can be pursued. Investigators as part of a large household survey may not be able to fill this role appropriately, so investigators

should consider managing this information in collaboration with the subject’s physician. The release of information to the subject’s physician would require the consent of the subject. Some subjects will not have a physician or may decline consent to have the information sent to their physician. In anticipation of these possibilities, the protocol could either provide for clinically experienced individuals to provide results and counsel to subjects through the project, or could decline to enroll these subjects. Providing clinical results can be labor intensive and expensive, so funding agencies should be prepared to support these efforts in welldesigned projects.

The NHANES III project returned clinically valid results to subjects directly through letters to the subjects. Subjects who had results that were medically concerning were advised to make an appointment with their physician. Whether subjects who were so advised utilized the information in an effective manner to improve their health status is unclear.

In other circumstances, analyses will be used that have no established clinical utility. There are no meaningful results to be returned to subjects in this situation and therefore returning research results typically has not been required by IRBs. It also is important to note that current federal regulations do not permit the return of results to patients or subjects if the tests were not conducted in a CLIA-approved2 laboratory (Holtzman and Watson, 1997). Since many research laboratories are not CLIA approved, results from these labs should not be returned to subjects. In some circumstances, repeating the test in a CLIA-approved lab may be feasible and appropriate. In any case, subjects should be clearly informed in the initial consent process whether or not they will receive individual results from the project.

There are two gray areas in this domain. The first arises when test results have not been fully validated by peer review, publication, and replication by other investigators, but for which there is solid reason to believe that the results have some validity. Whether it is appropriate to return the results will depend on several factors and should be subject to IRB review. First, how strong is the evidence of test validity? Second, what are the clinical implications of the test results? If the results could be used to treat or prevent serious disease, the impetus to return the results will be stronger. However, a corollary is that the impact of misinformation must also be weighed. Subjects may make burdensome, irreversible decisions based on information that ultimately may be proven false.

The second gray area is the appropriate response to results that gain

clinical utility with time. A test result may be impossible to interpret today but be meaningful to clinicians in 5 to 10 years. What is the responsibility of investigators to subjects who participated years ago in their protocols? Is there a “look back” responsibility to contact former subjects to alert them to health risks? In clinical medicine, a look back responsibility has been found in some situations. Physicians who inserted certain IUD’s in women were found to have a responsibility to contact those women years later when problems with the devices were identified (Andrews, 1997). In the research context, the relationship between investigator and subject is different than the relationship between doctor and patient, so it is unclear whether such a responsibility exists. A duty to recontact former subjects may be strongest when clinically relevant information was provided to subjects in the past, but that information is now considered incorrect or substantially incomplete. As noted by Clarke and Ray (1997), the limited guidance provided to clinicians on this issue tends to permit recontacting of patients with new genetic information but stops short of requiring recontact. It is possible in the future that courts will find investigators responsible for warning former research subjects when investigators have unique information that would be highly useful in reducing morbidity and mortality in former subjects and recontact is considered feasible.

A potential compromise solution in these gray areas is to send a follow-up newsletter to research subjects at the completion of the project, or even later if the situation warrants. A newsletter could contain general research results from the project, news on related developments, and recommendations on health care options. This approach can alert subjects to important changes in the field and encourage them to seek additional evaluation or advice from their own health care provider. This step may fulfill the responsibility of investigators to subjects without incurring the complexities and cost of providing individual results or follow-up.

Benefits of Participation

The benefits to subjects of household surveys with biologic sampling are likely to be minimal or nonexistent. When clinically valid tests are part of the protocol, such as cholesterol or blood pressure measurement, subjects may benefit from individual results provided conveniently without financial cost. However, assuming subjects are not being selected based on disease status and provided therapeutic interventions, survey projects are nontherapeutic research. The consent discussion and documents should state clearly that benefits cannot be expected by subjects. Of course, the pride and self-satisfaction that comes from contributing to a worthwhile research effort can be an intangible but substantial benefit.

Risks of Participation

The risks to participation are discussed in more detail by Durfy (2000) in this volume. In general, the risks of the physical intervention necessary to acquire a biologic sample are trivial. The primary risks to participation are psychosocial, meaning stigma and discrimination if sensitive information is generated in the project and there is a breach of privacy or confidentiality involving sensitive information. This may be the most significant consideration by potential subjects. As noted above, the degree of public concern over this issue may be greater than currently is justified by the data on discrimination. Whether this will become a serious problem in the future remains to be seen. Many reported instances of genetic discrimination are due to insurance or employment discrimination against people who are currently affected with genetic conditions (Lapham et al., 1996). Unfortunately this is a feature of our health care system in general, which does not guarantee health insurance coverage at affordable rates to those who are ill. People can lose their insurance or pay increased rates when they get sick from genetic and nongenetic conditions alike. The new feature of genetic discrimination is potential discrimination against those who are currently healthy, but who are highly susceptible to future illness based on genetic test results. Of course, this kind of discrimination need not be due to genetic testing alone. A survey that newly diagnosed subjects with hyperglycemia or significant hypertension would confer the same risks on subjects.

A further complexity of this issue arises from the different levels of risk of insurance or employment discrimination that different individuals will run. A retired woman on Medicare is at limited risk for employment or health insurance discrimination, and life or disability insurance discrimination is unlikely to be a problem. However, a self-insured young executive at a small company might be at substantially greater risk for discrimination for employment, as well as for all forms of insurance, if she were found to be at high risk for future illness. In addition, federal law and legislation in approximately 35 states provides some measure of protection against genetic insurance and/or employment discrimination (National Human Genome Research Institute). Therefore, unless comprehensive federal legislation is passed, a multistate household survey would approach potential subjects who have a complex mix of baseline risks for discrimination based on the results of testing.

The complexity of this issue is too great to be adequately covered in an informed consent document. Investigators who are enrolling subjects should be familiar with this issue in some detail so that the discussion can be tailored to the concerns and the life situation of the potential subject. It is simply not accurate to state or imply that all subjects are at risk for

insurance or employment discrimination. Indeed, it may be reasonable not to include any information about employment or insurance discrimination if the survey will not be collecting potentially sensitive information. If sensitive information is being collected, or might be generated in the tissue analysis, then the issues of stigma and discrimination should be included and recruiters should be prepared to discuss these topics. If insurance discrimination is an issue, it may be important to make subjects aware that the subjects themselves may be asked to disclose clinical or research results in the process of applying for an insurance policy.

An occasional risk in genetic research projects is the detection of misattributed paternity, that is, the finding that the subject’s social father is not his or her genetic father. A history of adoption also might be discovered through genetic testing, although this is a less common problem. These potential issues will arise only when samples are being obtained from one or both parents and their children. In the context of prenatal diagnosis or the diagnostic testing of children, knowledge of misattributed paternity is important in assessing the genetic risk to the couple’s future offspring. Therefore the information is often relayed to the mother and subsequently to the social father with the consent of the mother. In the context of household surveys, a finding of “nonpaternity” is likely to be incidental to the research effort and of no clear benefit to the research subjects (indeed, it may be quite harmful). Therefore it is probably inappropriate to communicate this incidental finding to family members. If misattributed paternity destroys the scientific value of the specimens, then an option is to remove the survey data and specimens from the project without retaining this sensitive information in a linked fashion. If the protocol calls for this information to be communicated to family members, then this risk must be part of the consent process. If misattributed paternity could be detected in a project, but the information will not be communicated or retained, then the IRB must use its discretion in deciding whether to inform potential subjects of this issue.

Privacy and Confidentiality Protections

Privacy and confidentiality are closely related concepts, although not identical. Confidentiality refers to maintaining the integrity of information shared by a subject within the professional relationship. The subject has a right to expect that personal information that he or she provides will only be shared with designated investigators or staff affiliated with the research. In contrast, privacy can be breached through the generation of new information about the subject without his or her consent. Therefore the analysis of a linked tissue sample to reveal the subject’s risk status for a disease without the explicit consent of the subject would constitute a

breach of privacy, whether or not the results were communicated outside the project. Indeed, telling subjects information about themselves that they did not want to know constitutes a breach of privacy.

As discussed above, privacy and confidentiality can be protected through a process of unlinking data and samples from individual identifiers. With linked samples, privacy risks can be addressed by explicitly discussing the extent of the research to be conducted with the sample. If identifiable specimens are to be retained in a repository, subjects might be offered a choice about the nature of research to be conducted with their tissue. If specimens are acquired primarily for research involving cancer, for example, it will be appropriate to offer a choice to make the tissue available only for cancer research, or for research addressing other health problems as well, assuming that prospect is anticipated by the investigators. If the consent process focuses exclusively on cancer research, then an IRB may not permit the sample to be used for noncancer-related work.

Recontacting Subjects for Consent

There remains some controversy over whether subjects should be asked to provide blanket consent for future research on linked samples. The American Society of Human Genetics Statement on Informed Consent for Genetic Research (1996) concludes: “It is inappropriate to ask a subject to grant blanket consent for all future unspecified genetic research projects on any disease or in any area if the samples are identifiable in those subsequent studies.” The National Bioethics Advisory Commission (1999) in its Recommendation 9 outlined six options that investigators might include in consent forms. Among these were the following (using NBAC’s outline letters and text):

-

permitting coded or identified use of their biological materials for one particular study only, with no further contact permitted to ask for permission to do further studies;

-

permitting coded or identified use of their biological materials for one particular study only, with further contact permitted to ask for permission to do further studies;

-

permitting coded or identified use of their biological materials for any study relating to the condition for which the sample was originally collected, with further contact allowed to seek permission for other types of studies; or

-

permitting coded use of their biological materials for any kind of future study.

One commissioner, Alexander Capron, objected to options (e) and (f), stating that subjects cannot provide a truly informed consent to future, unspecified studies. Since the risks and benefits of such studies are unknown, Capron does not believe it is appropriate for subjects to agree to the use of their coded samples without being recontacted for discussion and explicit consent. A second commissioner and NBAC Chair, Dr. Harold Shapiro, also objected to option (f), concurring with Capron’s analysis of this provision.

This is a critical debate for the protocol development for a household survey with sample collection. Ultimately, an IRB will determine whether recontacting the subject for consent is necessary for specific applications to use the samples. The IRB will determine whether the new proposed use is consistent with the original consent and whether the proposed use entails risks that require a new discussion with subjects. For example, we can imagine a repository that is established for investigators to seek new genetic markers for susceptibility to a number of diseases of older age, including, say, cancer, stroke, and osteoporosis. An investigator who approaches the repository with a proposal to do an exploratory search for markers for basal cell carcinoma on linked (or unlinked) samples may not be required by the IRB to recontact subjects. However, if the investigator would like to screen all tissue samples first for BRCA1/2, FAP and p53 mutations (established tests that reveal an increased risk for cancer), then the IRB is likely to require recontacting the subjects for detailed consent. Of course, the investigator may not know the identities of the tissue sources, but the repository does, and it would be left with a dilemma if the investigator reports to the repository that she found subjects who are mutation carriers on clinically valid tests to which the subject did not consent.

A potential solution to the problem of recontacting subjects for consent is to unlink samples that are distributed to investigators. This may limit their scientific value since investigators cannot re-access the survey database to expand their knowledge of the tissue sources. In addition, some members of the NIH/CDC Workshop (Clayton, 1995) expressed concern about unlinking samples since (1) recontacting subjects for consent is possible before the samples are unlinked, and (2) unlinking eliminates the ability to get back to subjects if clinically valuable information is generated in the research. In addition, unlinking samples does not avoid the risk of group or community harms to which subjects may object even if the samples are anonymous. In contrast, the College of American Pathologists recommends that a simple consent be considered sufficient for the subsequent research use of unlinked samples.

Withdrawal from Protocol

Federal guidelines require that the consent process include a statement that “participation is voluntary,…and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits.” In the context of a household survey in which there may be only a single contact with the subject, the definition of withdrawal from research is ambiguous. Certainly the investigators may choose the cleanest definition of withdrawal in this context by eliminating the subject’s data from the database and destroying the specimen and any samples that have been distributed, assuming they are identifiable. However, if analyses of the data or specimens have occurred prior to subject withdrawal, it is unclear whether withdrawal requires destruction of the research results derived from the individual. Particularly in genetic research, results from specific individuals may be key to analyzing genetic patterns in whole kindreds, so the loss of results from single individuals can be damaging to large projects.

If specimens or data are unidentified or unlinked, then subjects should be informed that these cannot be expunged or destroyed if a subject withdraws from the project. A potential option, subject to IRB approval, is to inform subjects that should they withdraw from the research, their data, specimens, and results to the time of withdrawal will be rendered unidentified (anonymous) but will continue to be used. This issue has not been the subject of commentary by the organizations that have developed guidelines on stored tissues.

Commercial Use of Specimens

Academic medicine and public agencies have an increasingly complex relationship with biotechnology companies that may seek to use resources developed for research or public health activities for the development of commercial products. Legal ownership of specimens collected for research remains unclear (Grizzle et al., 1999). Tissues cannot be sold by subjects or investigators, but they can be given away. In one of the few legal cases to address this issue, Moore v. the Regents of the University of California (1990), the court decided that tissues that have been transformed through the expertise of the investigators were no longer the property of the tissue donor. The College of American Pathologists’ statement concludes that professional products such as slides and tissue blocks created from subject specimens “can fairly be claimed as the property of the entity that produced them” (Grizzle et al., 1999). Whether specimens retained as frozen whole blood, urine, or cheek swabs would be considered the legal property of the investigators is unclear. In the Moore case,

the court found that the subject did not have a right to share in the commercial rewards derived from use of his tissues, but that investigators had an obligation to inform potential subjects when commercial products might result from their participation in research. Subjects who participate in research for altruistic reasons may decline participation if commercial enterprises are involved. It now is common for IRBs to require disclosure to potential subjects when commercial products might result from use of tissues and that, generally, subjects will not be provided a share of any profits from commercial use of their tissue.

Consent for Family Contact

If identifiable specimens are going to be retained and used for a prolonged period of time, investigators may wish to ask subjects to name a family contact who could be notified of results after the death or incapacity of the subject. If it is conceivable that the projects will pursue research with clinical relevance to family members (primarily blood relatives such as siblings and offspring), obtaining consent from subjects to contact a specified family member with information in the future may be beneficial to the family. We can imagine a scenario in which research identifies a new mutation for cancer susceptibility in a subject who has expired from cancer prior to the research results. If the name of a relative and a contact number have been provided by the subject, the relative can be contacted and provided with information about the research results and the implications for family members. Without a contact name and number, contacting family members may be difficult or impossible, and it may be unclear whether the subject would have consented to communication of his research results.

INCLUSION OF VULNERABLE SUBJECTS IN RESEARCH

Because children and mentally impaired individuals cannot provide informed consent for their participation in research, they are considered vulnerable populations. Specific federal regulations apply to children (Department of Health and Human Services, 1991). In brief, research involving no greater than minimal risk (as defined above) is permissible with the permission of the parents and assent of the older child (generally meaning about 7–9 years of age, at the discretion of the IRB). Research involving greater than minimal risk is permissible if:

-

there is a prospect of direct benefit to the individual subject (that is, therapeutic research);

-

there is no prospect of direct benefit to the child, but the research is

-

a minor increase over minimal risk and will yield vital, generalizable knowledge about the subject’s disorder or condition; or

-

there is no prospect for benefit but the research offers to prevent, alleviate or understand a serious problem affecting the health of children and the project is approved by the Secretary of Health and Human Services after consultation with a panel of experts.

Option (1) is not relevant to survey research and option (3) is pursued only rarely, if ever. Option (2) also is a poor fit for household survey research since such surveys typically do not target children with specific health disorders or conditions. Therefore a key question is whether research involving the acquisition of tissue samples involves greater than minimal risk. NBAC (1999:v) concluded: “IRB’s should operate on the presumption that research on coded samples is of minimal risk to the human subject if (a) the study adequately protects the confidentiality of personally identifiable information obtained in the course of research, (b) the study does not involve the inappropriate release of information to third parties, and (c) the study design incorporates an appropriate plan for whether and how to reveal findings to the sources of their physicians should the findings merit such disclosure.” However, the NIH/CDC Working Group (Clayton et al., 1995:1790) stated: “As is true for adults, research using linkable or identifiable tissue samples from children, particularly to search for mutations that cause specific diseases, usually poses greater than minimal risk.” The NIH/CDC Working Group proceeds to conclude that when the research involves more than minimal risk for children, permission of the parents and assent of the child is sufficient to allow the research to proceed. While this is true for therapeutic research, the regulations indicated that nontherapeutic research on healthy children should entail no more than minimal risk. Therefore an IRB’s interpretation of the minimal risk criterion will be critical for the inclusion or exclusion of children in such projects.

Particular concern has been expressed about genetic testing of children for adult onset conditions. The American Society of Human Genetics in collaboration with American College of Medical Genetics (ASHG, 1995), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (in press) have published statements that advise forgoing genetic testing for adult onset disorders unless there are measures that must be taken in childhood to reduce the morbidity or mortality of the condition. Children may be especially vulnerable to social stigma and discrimination based on predictive test results. Therefore any household survey research that included testing of linked specimens of children for serious adult onset disorders probably would be considered greater than minimal risk. Less sensitive information could be generated on children without superceding the minimal risk threshold, al-

though, of course, this determination ultimately must be made by an IRB. However, investigators will have to be cognizant of the burdens of tissue sampling itself for some children. For many children between the ages of about 1 to 6 years, a blood draw can cause substantial anxiety and may be considered greater than minimal risk. Alternative approaches to tissue sampling might be considered for this sensitive age group. With the new impetus at the federal level to include children in research, there is no reason in principle why children could not be participants in household surveys with the collection of biological specimens.

Inclusion of individuals who have lost decision making capacity, perhaps such as those with Alzheimer disease or stroke, might provide a valuable resource for research on these common problems. Federal guidelines for research involving mentally impaired subjects are less explicit than those for children. Recognizing mentally impaired persons as a vulnerable population, the Common Rule directs IRBs to include “additional safeguards…to protect the rights and welfare” of these subjects (NBAC, 1998:Appendix I). The Common Rule permits a mentally impaired subject’s “legally authorized representative” to give consent for the subject’s participation in research, but as the NBAC noted in its 1998 report on research with mentally impaired subjects, the Common Rule “provides no definitions of incapacity, no guidance on the identity or qualifications of a subject representative beyond ‘legally authorized’ and no guidance on what ratio of risks to potential benefits is acceptable” (NBAC, 1998: Appendix I). Therefore, under existing federal guidelines, inclusion of mentally impaired subjects in a household survey would require only the consent of a legally authorized representative of the subject, as interpreted and approved by an IRB. However, a number of states have legislated prohibitions on research with mentally impaired subjects that would have to be carefully evaluated in a national survey (NBAC, 1998: note 280). The National Bioethics Advisory Commission’s 1998 recommendations would not change these general guidelines if the research is deemed of minimal risk. However, if the research was considered to have greater than minimal risk without prospects of benefit to the subject, NBAC’s recommendations would require the protocol to be approved by a Special Standing Panel at the Department of Health and Human Services developed to address research issues with mentally impaired individuals. A Special Standing Panel for this purpose has not been established at the time of this writing.

FORMAT FOR CONSENT FORMS

Given the variety of choices that might be offered subjects in research involving tissue storage, a check-box format is coming into use. This

means a mini menu is provided to potential subjects on the consent form to allow them to pick and choose options about how their tissues will be used. Providing a variety of options is not necessary, but it has the advantage of being explicit about what the subject wants and may enhance recruitment of subjects who want only limited involvement. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1997) recommends the extensive use of this format. Of course, the problem with offering many choices is that it creates a complex stratification of subjects that is unlikely to be random. There also are significant administrative burdens to tracking what kinds of projects can be done with different samples.

Using this approach on a more limited basis, investigators might offer choices (documented on the form) including:

-

Acquisition of a biological sample and use in research;

-

Retention of specimens in an identified or unidentified form;

-

Whether research can be conducted using the subject’s specimen for health issues beyond the primary focus of the initial project;

-

Whether the subject permits recontact for additional survey data or consent for use of linked specimens for studies beyond the primary focus of the initial project; and

-

Consent to provide results to a designated family member if the subject is deceased or incompetent.

CONCLUSIONS

The concept of informed consent often has a poor reputation among clinicians and investigators. Consent may been seen as a perfunctory exercise in response to a litigious society, and/or as a futile effort to quickly educate laypersons in complex medical concepts. Indeed, subjects often have a poor recollection of basic research facts, and may even forget that they are involved in research (Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments, 1995). Whether this reflects the inherent impossibility of achieving an ideal informed consent, or whether it reflects the inadequacies of our efforts to obtain informed consent is unclear. Current regulations and standards, while burdensome, are based on clear episodes of abuse of subjects in research. There is often an inherent conflict between the welfare of subjects and the pursuit of knowledge. Thoughtful guidelines and careful peer review are essential. More importantly, subjects should be viewed and treated as collaborators in the research endeavor. To the best of the investigator’s ability, and to the limit of the subject’s interest and understanding, the ideal is that conversations about projects should proceed as between collaborators, albeit with very differ-

ent roles to play. Additional research on how subjects view all of these issues is essential.

The preceding points to consider are lengthy and occasionally complex, but they reflect a contemporary sensitivity to risks associated with powerful new technologies. Many of the risks of stigma and discrimination may prove to be overstated, and excessive caution now may slow the progress of research. Nevertheless, the alternative to caution risks generating useless samples through insufficient planning or, worse, a breach in public trust that will impair the integrity of the research enterprise and only further delay the substantial benefits this work offers.

REFERENCES

Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments 1995 Final Report of the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Allen, A.L. 1997 Genetic privacy: Emerging concepts and values. Pp. 31–59 in Genetic Secrets: Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality in the Genetic Era, M.A.Rothstein, ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics in Ethical Issues with Genetic Testing in Pediatrics, press

American College of Medical Genetics 1995 Statement on storage and use of genetic materials. American Journal of Human Genetics 57(6):1499–1500.

American Society of Human Genetics 1996 Statement on informed consent for genetic research. American Journal of Human Genetics 59:471–474.

American Society of Human Genetics, American College of Medical Genetics 1995 Points to consider: Ethical, legal, and psycho-social implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. American Journal of Human Genetics 57:1233–1241.

Andrews, L. 1997 The genetic information superhighway: Rules of the road for contacting relatives and recontacting former patients. Pp. 133–143 in Human DNA: Law and Policy: International and Comparative Perspectives, B.M.Knoppers, C.M.Laberge, and M. Hirtle, eds. Boston: Kluwer Law International.

Annas, G.J. 1993 Privacy rules for DNA databanks: Protecting coded “future diaries.” Journal of the American Medical Association 270:2346–2350.

Annas, G.L., L.H.Glantz, and P.A.Roche 1995 Drafting the genetic privacy act: Science policy, and practical considerations. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 23:360–365.

Caplan, A. 1992 When evil intrudes (In a series “Twenty years after: The legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis study”). Hastings Center Report 22(6):29–32.

Clarke, J.T.R., and P.N.Ray 1997 Look-back: The duty to update genetic counselling. Pp. 121–132 in Human DNA: Law and Policy: International and Comparative Perspectives , B.M.Knoppers, C.M. Laberge, and M.Hirtle, eds. Boston: Kluwer Law International.

Clayton, E.W., K.K.Steinberg, M.J.Khoury, E.Thomson, L.Andres, M.J.E.Kahn, L.M. Kopelman, and J.O.Weiss 1995 Informed consent for genetic research on stored tissue samples. Journal of the American Medical Association 274:1786–1792.

Coombs, M. 1999 A brave new crime free world? Pp. 227–242 in Genetics and Criminality: The Potential Misuse of Scientific Information in Court, J.Botkin, W.McMahon, and L.Francis, eds. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association Press.

Department of Health and Human Services 1991 Code of federal regulations. Title 45, Part 46: Protection of human subjects. Federal Register 56:28003. June 18.

Foster, M.W., D.Bernsten, and T.H.Carter 1998 A model agreement for genetic research in socially identifiable populations. American Journal of Human Genetics 63:696–702.

Freedman, W. 1998 The role of community in research with stored tissue samples. Pp. 267–301 in Stored Tissue Samples: Ethical, Legal and Public Policy Implications, Robert Weir, ed. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Fuller, B.P., M.J.E.Kahn, P.A.Barr, L.Biesecker, E.Crowley, J.Garber, M.K.Mansoura, P. Murphy, J.Murray, J.Phillips, K.Rothenberg, M.Rothstein, J.Stopher, G.Swergold, B. Weber, F.S.Collins, and K.L.Hudson 1999 Privacy in genetic research. Science 285:1359–1361.

Grizzle, W., W.W.Grody, W.W.Noll, M.E.Sobel, S.A.Stass, T.Trainer, H.Travers, V. Weedn, and K.Woodruff 1999 Ad Hoc Committee on Stored Tissues, College of American Pathologists. Recommended policies for uses of human tissue in research, education and quality control. Archives of Pathological Laboratory Medicine 123(4):296–300

Holtzman, N.A., and M.S.Watson, eds. 1997 Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the United States. Final Report of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. NIH-DOE Working Group on Ethical Legal and Social Implications of Human Genome Research, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD.

Kipnis, K. 1998 DNA banking in the military: An ethical analysis. Pp. 329–344 in Stored Tissue Samples: Ethical, Legal and Public Policy Implications, Robert Weir, ed. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Lapham, V., et al. 1996 Genetic discrimination: Perspectives of consumers. Science 274:621–624.

McEwen, J.E. 1998 Storing genes to solve crimes: Legal, ethical, and public policy considerations. Pp. 311–328 in Stored Tissue Samples: Ethical, Legal and Public Policy Implications, Robert Weir, ed. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Moore v. the Regents of the University of California 1990 793 P2d 479 (Cal 1990).

Murray, T.H. 1997 Genetic exceptionalism and “future diaries”: Is genetic information different from other medical information? Pp. 60–73 in Genetic Secrets: Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality in the Genetic Era, M.A.Rothstein, ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) 1998 Research involving persons with mental disorders that may affect decision making capacity. [Online]. Available: http://bioethics.gov/capacity/TOC.htm.

1999 Research involving human biological materials: ethical issues and policy guidance. [Online]. Available: http://bioethics.gov/pubs.html.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1997 Report of the Special Emphasis Panel: Opportunities and Obstacles to Genetic Research in NHLBI clinical Studies. [Online]. Available: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/meetings/workshops/opporsep.htm.

National Human Genome Research Institute http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Policy_and_public_affairs/Legislation/insure.htm

Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR), National Institutes of Health 1997 Issues to consider in the research use of stored data or tissues. November 7. [Online]. Available: http://www.nih.gov/grants/oprr/humansubjects/guidance/reposit.htm.

Steinberg, K.K., E.J.Sampson, G.M.McQuillan, and M.J.Khoury 1998 Use of stored tissue samples for genetic research in epidemiologic studies. P. 83 in Stored Tissue Samples: Ethical, Legal and Public Policy Implications, Robert Weir, ed. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Wallace, R.B. 1997 The potential of population surveys for genetic studies. Pp. 234–244 in Between Zeus and the Salmon: The Biodemography of Longevity, K.W.Wachter, and C.E.Finch, eds. Washington DC: National Academy Press.