Page 1

Executive Summary

The quality of health care received by the people of the United States falls far short of what it should be (Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry, 1998; Chassin and Galvin, 1998). A large body of literature documents serious quality problems. There is a gap (some say a “chasm”) between the health care services that should be provided based on current professional knowledge and technology and those that many patients actually receive (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 1999; Schuster et al., 2001). For example, the National Cancer Policy Board of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has concluded that “for many Americans with cancer, there is a wide gulf between what could be construed as the ideal and the reality of their experience with cancer care” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 1999). Another IOM report documented that tens of thousands of Americans are seriously harmed as a result of errors in health care (Institute of Medicine, 2000).

Enormous resources are invested in health care. In 1998, national health care expenditures topped $1.1 trillion or 13.5 percent of the gross domestic product (Levit et al., 2000). Americans spend $4,270 per person per year on health care, an amount in excess of that spent by any other country (Anderson et al., 2000). Is this money well spent? Is it translated into quality care and improved health? Today, it is not possible to answer these questions satisfactorily.

It is clear that all resources are not used effectively or safely. Study after study documents the overuse of many services—the provision of services when the potential for harm outweighs possible benefits. At the same time, studies

Page 2

also document the underuse of other services—the failure to provide services from which the patient would likely have benefited (Chassin and Galvin, 1998).1 Patient safety was the subject of a landmark report by the IOM (2000).

It is these and other shortcomings in quality that led the President's Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry to call for a national commitment to improve quality involving both the private and the public sectors and every level of the health care system (Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry, 1998). To help guide this process and track progress, the Advisory Commission recommended that there be an annual report to the President and Congress on the nation's progress in improving health care quality. Shortly thereafter, Congress enacted the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999, directing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to prepare an annual report on national trends in the quality of health care provided to the American people.

AHRQ contracted with the IOM to assist in the design of the new national health care quality report. The IOM Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery was established in 1999 and was charged with laying out a vision of the National Health Care Quality Report (also referred to as the Quality Report), including both its content and its presentation. Specifically, the committee was asked to

-

identify the most important questions to answer in evaluating whether the health care delivery system is providing high-quality health care and whether quality is improving over time;

-

identify the major aspects of quality that should be reflected in the Quality Report;

-

provide examples of specific measures that might be included in the Quality Report; and

-

provide advice on the format and production of the report.

PURPOSE OF THE NATIONAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY REPORT

The National Health Care Quality Report should serve as a yardstick or barometer by which to gauge progress in improving the performance of the health care delivery system in consistently providing high-quality care. Similar tools have been applied and found useful in other areas and industries. For example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics produces economic indicators, such as the

1 For a review of more than 70 articles documenting shortcomings in quality of care see Schuster et al., 2001.

Page 3

Consumer Price Index (CPI), to track the state of the economy. This information is used to establish economic policies that promote sound economic growth (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000). In another sector, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report tracks educational performance. This information is used to guide educational reform, including changes in curriculum and instruction (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000; National Research Council, 1998, 2000, 2001).

The Quality Report should complement other reports produced on the health of the people of the United States by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Health United States examines health status annually (National Center for Health Statistics, 2000). Healthy People 2010 sets forth 467 public health objectives for the coming decade (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000a). While these efforts focus on tracking and improving the public's health, the Quality Report should focus on the performance of the health care delivery system with regard to personal health care, rather than public health functions. It should examine the quality of care provided to the general population and major subgroups by the system as a whole and not care delivered in specific health care settings or by specific providers. In this respect, it differs from the comparative “report cards” issued by other organizations, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), which inform purchaser and consumer choice of health plans (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2000).

The Quality Report should present a “broad-brush” portrait of quality of care to inform Congress and national policy, while more detailed performance reports at the provider, institutional, and local levels would be used for specific quality improvement efforts. The Quality Report is intended to complement another report mandated by Congress in the same legislation. This second report, which is under development, will address “disparities in health care delivery as it relates to racial and socioeconomic factors in priority populations” (Healthcare Research and Quality Act, 1999:Sec. 902). The importance of articulating these two efforts cannot be overemphasized. While there may be some overlap between the two, the committee recommends that the Quality Report present appropriate information on equity by geographic region and population subgroup, as discussed later. It is the committee's understanding that the disparities report will include in-depth analyses of any differences that may be present in various aspects of health care delivery, including quality. The committee views the Quality Report as one of the components of a multilevel reporting system that will eventually cover local to national levels and span a variety of topics, all of which are needed to examine both health care delivery and the health status of the people of the United States.

The committee believes that the Quality Report should satisfy several objectives:

Page 4

-

Enhance awareness of quality. An annual report on the state of quality can serve as an important vehicle of communication to improve awareness and understanding of quality issues by policy leaders, health care professionals, and the lay public.

-

Monitor possible effects of policy decisions and initiatives. Many efforts are currently underway in both the public and the private sectors to improve quality. Tracking key aspects of the health care system's performance over time will be critical to assessing the impact of these improvement efforts and other policy initiatives, including budgetary changes. For example, if Congress enacts Medicare prescription coverage, the Quality Report could potentially be one of several instruments used to examine whether this change has contributed to improved blood pressure control among seniors.

-

Assess progress in meeting national goals. If health care leaders choose to develop specific goals for improvement in the health care delivery system (for example, to achieve a 50 percent reduction in adverse drug events over the next five years), the Quality Report can be used to track progress in meeting these goals. The coupling of an annual reporting mechanism with specific goals for improvement is an approach that has worked well in other sectors.

The committee concluded that if these objectives are met, the Quality Report can provide a much-needed source of authoritative information to answer key questions about the quality of care. It should be useful in determining whether the quality of health care is improving, staying the same, or worsening over time. It should help assess whether progress is being made in improving specific aspects of quality, including safety, effectiveness, “patient centeredness,” and timeliness. The report should also help ascertain whether the health care system is responsive to consumers' needs and preferences for care. To do so, the Quality Report should include a wide range of measures that reflect consumer perspectives and different needs for care when they are healthy, experience acute illness, need to manage a chronic illness, or are coping with the end of life.

The report design should be flexible enough to allow for exploration of special questions that affect different groups of the population, such as

-

variations in the quality of care received by people residing in different geographic areas (for example, states);

-

assessment of the quality of care received by people with a specific health problem or condition (for example, diabetes); and

-

variations in the quality of care based on personal characteristics unrelated to health (for example, ethnicity, race, gender, age, health insurance coverage).

Page 5

DEFINING A VISION FOR THE NATIONAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY REPORT

The committee went through a four-step process to define a vision for the National Health Care Quality Report:

-

development of the conceptual framework,

-

specification of criteria for selecting measures and identification of sample measures,

-

specification of criteria for selecting data sources and identification of potential data sources, and

-

development of audience-centered reporting criteria.

First, the committee formulated a conceptual framework for the Quality Report. To do so, the committee considered both the key questions to be answered and the major aspects of quality that should be measured to answer these questions. Conceptual frameworks used by other public- and private-sector groups engaged in quality measurement and improvement were reviewed and built upon whenever possible. Throughout its endeavors, the committee strived to make its work synergistic with that of others and to avoid “reinventing the wheel.”

Second, having specified a conceptual framework, the committee turned its attention to the process of selecting examples of the type of measures that should be included in the Quality Report. The committee has developed criteria to guide the final selection of measures that address each of the major components of quality. The committee was also asked to provide examples of measures for the Quality Report. More than 130 measures were submitted by organizations and individuals in response to a call for measures issued to the private sector by the committee in June and July 2000.2 The committee examined these and other potential measures identified through a review of the literature and selected a limited number to serve as examples of those that might be included in the Quality Report.

Third, potential public and private sector data sources that might be drawn on to produce measures in the Quality Report were identified and evaluated based on specific criteria defined by the committee. The committee concluded that no single existing data source can satisfy all of the requirements of the Quality Report, but much progress can be made by drawing on a mosaic of data sources, including consumer and provider surveys, clinical or medical record data, and administrative data.

Lastly, the committee identified the main audiences for the Quality Report and developed guidelines for the design and production of reports tailored to these audiences. Although its primary audience is intended to be health care

2 AHRQ issued a separate call for measures to federal agencies after the committee had concluded its deliberations.

Page 6

policy makers and leaders at the national and state levels, the Quality Report should also be of keen interest to the lay public, clinicians, purchasers, researchers, and others. The Quality Report is not envisioned as a single static report, but rather as a collection of annual reports tailored to the needs and interests of particular constituencies.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

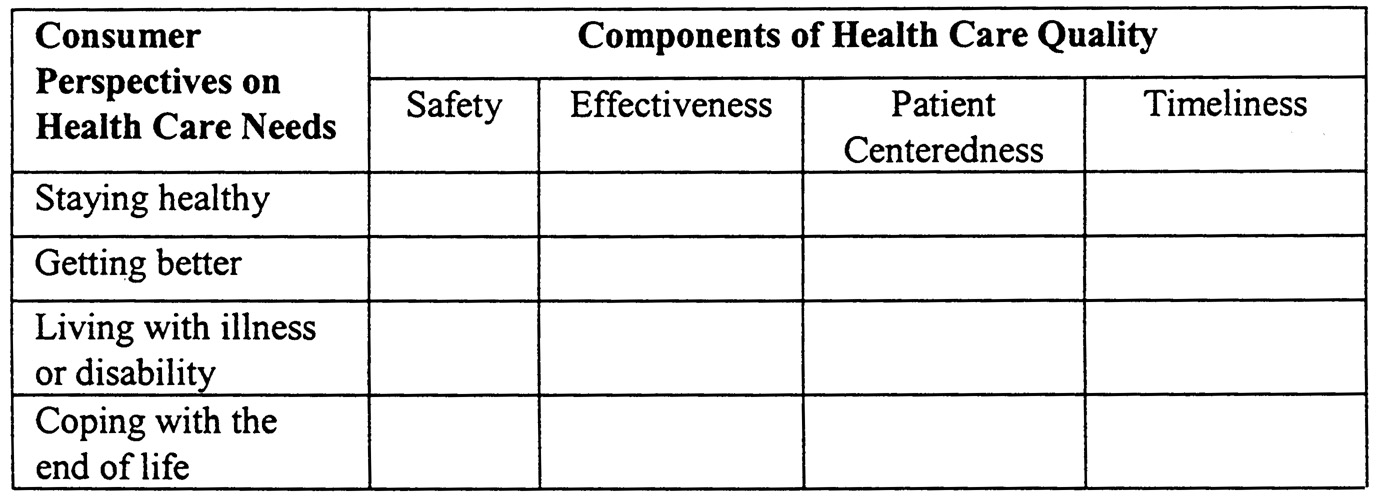

RECOMMENDATION 1: The conceptual framework for the National Health Care Quality Report should address two dimensions: components of health care quality and consumer perspectives on health care needs. Components of health care quality—the first dimension—include safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, and timeliness. Consumer perspectives on health care needs—the second dimension—reflect changing consumer needs for care over the life cycle associated with staying healthy, getting better, living with illness or disability, and coping with the end of life. Quality can be examined along both dimensions for health care in general or for specific conditions. The conceptual framework should also provide for the analysis of equity as an issue that cuts across both dimensions and is reflected in differences in the quality of care received by different groups of the population. (See Chapter 2.)

As a starting point, the committee adopted the following IOM definition of health care quality: “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Institute of Medicine, 1990:21). With its emphasis on “desired health outcomes,” this definition incorporates consumer perspectives on quality, while clearly linking quality to making the best use of current medical knowledge and technology. The definition also recognizes that there are population- and individual-level considerations that must be balanced when defining and assessing quality. For example, the health care provided to some patients may be excellent, yet the outcomes for the entire population that should be served by the system may fall short.

To operationalize this definition, the committee developed a two-dimensional framework. The framework is intended to provide a stable foundation for the Quality Report and specifies the aspects that should be measured while the individual measures may change over time in response to new health care practices and improvements in quality measurement. The first dimension of the framework captures the components of health care quality—safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, and timeliness.

Page 7

-

Safety refers to “avoiding injuries to patients from care that is intended to help them” (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Improving safety means designing and implementing health care processes to avoid, prevent, and ameliorate adverse outcomes or injuries that stem from the processes of health care itself (National Patient Safety Foundation, 2000). For instance, unsafe care occurs when a pharmacist misreads a hand-written prescription for a patient and dispenses a higher dosage than actually ordered by the physician.

-

Effectiveness refers to “providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit, and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding overuse and underuse)” (Institute of Medicine, 2001). For instance, effective care means that patients who experience a heart attack and do not have specific contraindications should receive beta-blockers.

-

Patient centeredness refers to health care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they require to make decisions and participate in their own care. For instance, if a woman with breast cancer undergoes a mastectomy without being fully informed about the various treatment options, given the nature of her cancer, that care was not patient centered.

-

Timeliness refers to obtaining needed care and minimizing unnecessary delays in getting that care. For instance, a woman who discovers a lump in her breast has received timely care if she is able to see her clinician, have the lump biopsied, and be informed of the results within a short and appropriate period of time.

The second dimension of the framework reflects consumer perspectives on health care needs or reasons for seeking care. It assesses health system performance in meeting changing consumer needs over the life cycle, which—depending on health status—could be to stay healthy, get better, live with illness or disability, or cope with the end of life (Foundation for Accountability, 1997). These consumer perspectives on health care needs are roughly equivalent to different types of health care as often defined by clinicians—preventive care, acute care, chronic care, and end-of-life care.

In addition to the two dimensions of quality components and consumer health care needs, the framework incorporates equity as a crosscutting issue, and the committee recommends that information in the Quality Report be presented by population subgroups when appropriate. The committee understands that the more in-depth, causal analysis, including issues of access and insurance, will be presented in the planned disparities report, mentioned earlier (Healthcare Research and Quality Act, 1999) and in publications related to Healthy People 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

For the Quality Report, the committee views equity as the provision of health care of equal quality to those who may differ in personal characteristics

Page 8

that are not inherently linked to health, such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, socioeconomic status, or insurance coverage. Equity means that the quality of care is based on needs and clinical factors. For example, care is provided equitably when an elderly African-American man and an elderly white man with prostate cancer and similar clinical profiles are both presented with complete information on the full range of treatment options and receive surgical and medical care of the same quality. Finally, the framework contemplates the measurement of quality of care for people with specific health conditions, particularly in the context of consumer health care needs. For example, the report can be used to examine whether persons with diabetes are receiving the care they need to manage or “live with their illness” or whether children are “staying healthy” by receiving indicated immunizations at the appropriate ages.

The combination of components of health care quality and consumer perspectives on health care needs defines the types of measures that should be in the National Health Care Quality Report, and can be represented as a matrix ( Figure 1). The matrix is a tool to visualize possible combinations of the two dimensions of the framework and better understand how various aspects of the framework relate to each other. Not all combinations will be relevant to evaluate quality, not all cells will be equally important to all audiences, and the availability of measures for each cell will vary. Both health conditions and population characteristics related to equity would be issues that apply within each cell of the matrix.

~ enlarge ~

FIGURE 1 Classification matrix for measures for the National Health Care Quality Report.

For example, if the Quality Report is to include measures of quality of care for prostate cancer, the effectiveness–getting better cell might include a measure of whether patients undergoing prostatectomies were those for whom the likely benefits of the procedure exceeded the risks. The patient centeredness–getting better cell could have measures of whether patients were given the opportunity

Page 9

and information needed to make an informed choice between medical and surgical interventions.

The scope of the Quality Report is limited to quality of care. Thus, efficiency is not included in the framework. The committee does consider efficiency to be an important goal of the health care system that is related to, but conceptually different from, quality of care. Waste robs the health care system of scarce monetary and other resources that could be used to improve quality (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Specific causes of inefficiency, such as repeat procedures due to error, overuse, fragmentation of care, and unnecessary delays, are included under the appropriate component of quality. In the future, information on costs could be combined with information on the quality of care to provide an indication of whether the country is in effect using these resources to enhance the value received from health care spending.

SELECTING MEASURES FOR THE NATIONAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY REPORT AND DATA SET

RECOMMENDATION 2: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality should apply a uniform set of criteria describing desirable attributes to assess potential individual measures and measure sets for the content areas defined by the framework. For individual measures, the committee proposes ten criteria grouped into the three following sets: (1) the overall importance of the aspects of quality being measured, (2) the scientific soundness of the measures, and (3) the feasibility of the measures. For the measure set as a whole, the committee proposes three additional criteria: balance, comprehensiveness, and robustness. (See Chapter 3. )

These are ideal criteria and should not be interpreted as strict requirements for potential measures. In the short term, all criteria referring to feasibility and/or scientific soundness may not always be fulfilled. The evaluation of measures based on the proposed criteria can be used to pinpoint areas for improvement in measure development.

Individual measures selected for the Quality Report should ideally rate highly for all criteria. However, importance and scientific soundness take precedence over feasibility. Feasibility criteria may have to be relaxed initially to allow for new or improved measures, given the fact that many of the aspects of quality that must be addressed have never been measured. The specific questions that can be used to examine whether or not a particular measure should be selected for the Quality Report are listed below.

Page 10

Importance of What Is Being Measured

-

What is the impact on health associated with this problem?

-

Are policy makers and consumers concerned about this area?

-

Can the health care system meaningfully address this aspect or problem?

Scientific Soundness of the Measure

-

Does the measure actually measure what it is intended to measure?

-

Does the measure provide stable results across various populations and circumstances?

-

Is there scientific evidence available to support the measure?

Feasibility of Using the Measure

-

Is the measure in use?

-

Can the information needed for the measure be collected in the scale and time frame required?

-

How much will it cost to collect the data needed for the measure?

-

Can the measure be used to compare different groups of the population (for example, by health conditions, sociodemographic characteristics, or states)?

It is also important that the set of measures as a whole is balanced, comprehensive, and robust. For this purpose, the committee recommends that three questions be asked: (1) Does the measure set reflect both what is being done well and what is being done poorly? (2) Can the measure set be used to portray the state of quality of health care delivery as a whole; that is, does it cover all of the elements in the framework? (3) Is the measure set relatively stable and robust, that is, not extremely sensitive to minor changes in the system not associated with quality?

RECOMMENDATION 3: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality should have an ongoing independent committee or advisory body to help assess and guide improvements over time in the National Health Care Quality Report. (See Chapter 3.)

Given the complexity of designing and producing the Quality Report, AHRQ should obtain advice from an independent advisory body. This advisory body should support the agency on the various processes associated with defining and updating the measures for the report, as well as designing and producing the report. It should include experts and representatives from organizations experienced in the development, evaluation, and application of specific quality measures. Members should be drawn from organizations in both the public and

Page 11

the private sectors, and should include national- as well as state-level representatives. The advisory body could be analogous to the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) or the National Quality Forum (NQF) (National Quality Forum, 2000; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000b). It should also serve as a vehicle for collaboration among interested public and private sector parties with the goal of improving quality measurement and reporting at the national level.

RECOMMENDATION 4: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality should set the long-term goal of using a comprehensive approach to the assessment and measurement of quality of care as a basis for the National Health Care Quality Data Set. (See Chapter 3.)

A comprehensive system is one in which the majority of care for a given population is assessed using a large number of measures representing the many components of health care quality and consumer perspectives on health care needs in an integrated manner. This approach should result in a more complete and accurate picture of the state of quality in the nation than is now available. To this end, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality should evaluate current efforts to develop comprehensive quality measurement systems (for example, in the area of effectiveness) and examine how they may be used and expanded.

One example of a comprehensive approach to measurement is the QA Tools system developed by RAND. The QA Tools system consists of more than 1200 quality measures (or indicators of effectiveness) applicable to 58 clinical areas (including conditions and recommended preventive services) and covering children, adults, and the vulnerable elderly. At present, application of the QA Tools requires abstraction of a sizable sample of medical records. For each medical record in the sample, information is abstracted on the subset of quality measures applicable to the patient given his or her gender, age, condition, and health risk profile. This information is then aggregated across the entire sample of individuals to produce an overall measure of the degree to which the care provided to this population is consistent with the care that should have been provided based on scientific evidence.

The committee sees potential promise in this kind of comprehensive approach to measuring effectiveness but believes that it would be premature to recommend using the QA Tools system in the National Health Care Quality Report at this time. First, the system was developed only recently, is still being revised, and has not yet been subject to an independent evaluation. Second, application at this time would impose a sizable burden in terms of medical record abstraction.

Page 12

The committee does think that comprehensive approaches to measurement, such as the RAND QA Tools system, merit careful evaluation. The continued development of increasingly standardized, electronic clinical data systems as part of a new health information infrastructure should make comprehensive measurement approaches more feasible and less burdensome in the future. It may also be possible, over time, for such approaches to incorporate measures of safety, patient centeredness, and timeliness, in addition to effectiveness. AHRQ, with the advice of the independent advisory body, should periodically revisit the issue of how best to start implementing a comprehensive approach to measurement for the National Health Care Quality Report.

RECOMMENDATION 5: When possible and appropriate, and to enhance robustness, facilitate detection of trends, and simplify presentation of the measures in the National Health Care Quality Report, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) should consider combining related individual measures into summary measures of specific aspects of quality. AHRQ should also make available to the public information on the individual measures included in any summary measure, as well as the procedures used to construct them. (See Chapter 3.)

The National Health Care Quality Report and Data Set should make use of summary measures to represent each of the framework's measure categories (for example, safety) or subcategories. This will facilitate the presentation of information on a very complex subject. In general, the measures combined should be based on the same population or have the same denominator and unit of measurement. That is, summary measures should combine like with like. The committee does not believe that an overall summary measure of quality would be useful or scientifically sound at this time, given that it would have to combine very disparate aspects of quality.

Summary measures should be specific enough to guide policy. The method and sources behind them should be stated clearly and made available. Presenting these summary measures along with a corresponding reference point or benchmark (for example, past performance, desirable level of performance, or average performance at the national level when presenting information for states) would provide a useful context for interpreting of the actual number being reported.

Summary measures have been used in public reporting in many other fields. Properly presented, they would make information more accessible to the public. In economics, for example, the Consumer Price Index is a summary measure of inflation that reflects the average price of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000). In the Quality Report summary measures could be used to assess specific aspects of safety of care or any of the other quality components. For example, a report could include a

Page 13

summary measure of the safety of surgery based on measures for a variety of surgical procedures.

RECOMMENDATION 6: The National Health Care Quality Data Set should reflect a balance of outcome-validated process measures and condition- or procedure-specific outcome measures. Given the weak links between most structures and outcomes of care and the interests of consumers and providers in processes or practice-related aspects as well as outcome measures, structural measures should be avoided. (See Chapter 3.)

The committee recommends that the National Health Care Quality Report and Data Set rely on a balanced set of process and outcome measures and avoid structural measures. Structural measures of the organizational, technological, and human resources infrastructure of the health care system (Donabedian, 1966) have not been shown to be consistently linked to the quality of care and desired outcomes. A combination of process and outcome measures will satisfy the needs of policy makers, clinicians, and consumers. Any measures for the National Health Care Quality Report and Data Set should not stifle innovation by institutionalizing specific processes or infrastructure that could soon become outdated.

SELECTING SOURCES FOR THE NATIONAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY DATA SET

RECOMMENDATION 7: Potential data sources for the National Health Care Quality Data Set should be assessed according to the following criteria: credibility and validity of the data, national scope and potential to provide state-level detail, availability and consistency of the data over time and across sources, timeliness of the data, ability to support population subgroup and condition-specific analyses, and public accessibility of the data. In addition, in order to support the framework, the ensemble of data sources defined for the National Health Care Quality Data Set should be comprehensive. (See Chapter 4.)

The data sources that are intended to support the long-term goal of a National Health Care Quality Data Set must meet certain high standards to support analysis of the state of health care quality in the United States. Although these criteria are not exhaustive, they do include the essential ideal features that should characterize data sources for the Quality Report in the future. When current data collection efforts do not fulfill these criteria, AHRQ should explore ways to enhance existent data sources and establish new data collection and

Page 14

reporting systems that exhibit these characteristics, in collaboration with the appropriate entities in the public and private sectors.

RECOMMENDATION 8: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality will have to draw on a mosaic of public and private data sources for the National Health Care Quality Data Set. Existent data sources will have to be complemented by the development of new ones in order to address all of the aspects included in the proposed framework and resulting measure set. Over the coming decade, the evolution of a comprehensive health information infrastructure, including standardized, electronic clinical data systems, will greatly facilitate the definition of an integrated and comprehensive data set for the Quality Report. (See Chapter 4.)

A preliminary and limited evaluation of several candidate data sources suggests that a combination of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS) may have the best potential to supply data for measures of patient centeredness and aspects of timeliness. However, the CAHPS component presently planned for MEPS will have to include additional questions in order to meet the data requirements for these two components of quality and related consumer perspectives on health care needs. To assess effectiveness and safety, as well as relevant health care needs, a combination of public and private data sources should be used, including MEPS, other population surveys, claims and other administrative data, medical record abstraction, and new data sources that will have to be developed.

The committee considers that this effort will require an assessment of the investment needed to create and maintain appropriate data systems to support the annual production of the Quality Report. Whenever possible, the committee recommends that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality pursue data strategies that encourage the collection of electronic clinical data as a part of the care process. Although there are many clinical and administrative reasons for the use of standardized electronic information, in the long run, this type of information will also provide the best data on both the system's quality components and consumer health care needs.

Early versions or editions of the Quality Report will have to rely on existent data sources, but they should shed light on some very important aspects of quality. They will also develop consumer and policy-maker expectations for ongoing reports on the quality of health care. Over time, the Quality Report should present a more textured and comprehensive view of quality as the health care sector develops a more sophisticated health information infrastructure.

Page 15

RECOMMENDATION 9: The data for the National Health Care Quality Report should be nationally representative and, in the long term, reportable at the state level. (See Chapter 4.)

By measuring health care quality at the national and state levels, the National Health Care Quality Report would provide benchmarks to judge how well health care delivery systems are performing at the state level relative to the degree of quality achieved for the nation as a whole. The ability to examine certain quality measures across states would substantially enhance the policy relevance, visibility, and usefulness of the report. In some cases, the sample size may have to be increased in order to produce more precise state-level estimates. States should be given the option of acquiring additional sample size when the data available nationally are not sufficient to conduct state-level analyses for populations of interest. Local-level identifiers such as zip codes can be used to examine specific subpopulations when needed. Since health care is inherently a local phenomenon, further detail on the quality of care for geographic units smaller than states is usually required to address potential problems at the provider and organizational levels. However, this level of detail should generally correspond to regional or specialized reports since the purpose of the National Health Care Quality Report is to examine the quality of care provided by the system as a whole, not by individual providers, localities, or health plans.

DESIGNING THE NATIONAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY REPORT

RECOMMENDATION 10: The National Health Care Quality Report should be produced in several versions tailored to key audiences—policy makers, consumers, purchasers, providers, and researchers. It should feature a limited number of key findings and the minimum number of measures needed to support these findings. (See Chapter 5.)

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality should produce a National Health Care Quality Report, or collection of reports, that will attract the attention and interest of national and state policy makers, consumers, purchasers, providers, and researchers. Policy makers should be able to act on the findings presented in the report by formulating legislation or designing programs, for example. The National Health Care Quality Report will be an important tool that AHRQ can use to promote a better understanding of quality, generate support for improvement, and highlight areas that require special attention. The Quality Report should inform the public and provide a context for accountability of the health care system.

Page 16

To accomplish these goals, AHRQ should make the Quality Report relevant, engaging, easy to read, and easy to understand. The print version should be brief and aimed at key audiences. It should summarize key findings on specific topics. For example, the topics might include quality of care for diabetics, quality of care for children, and quality of preventive care.

There should be different versions of the report, that is, a collection or family of reports, available in print and on a dedicated web site. The web site should also include a user-accessible version of the complete data set to the extent feasible. The family of reports should be tailored to specialized audiences, as well as the general public. The content should be highly selective, relevant to current policy concerns, and fresh from year to year, even while preserving some continuity. Finally, the format employed should be designed so that differences across regions or groups and trends are easily discernible.

CONCLUSION

In this report, the IOM Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery provides the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality with a vision of the contents and design of the National Health Care Quality Report. It defines the aspects of quality that should be measured, describes the characteristics of desirable measures and data sources, provides specific examples of measures, and proposes a set of criteria for designing and producing the Quality Report.

The committee recognizes the difficulties involved in achieving the vision presented here, but the changes required are necessary in order to be able to assess and track quality of care adequately. Some measures available do not fit all of the criteria proposed and will have to be improved. For certain elements of the framework completely new measures will have to be developed, but past experience with measures for Healthy People 2000 has shown that this is feasible (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1991, 2000). For the Quality Report to provide a comprehensive picture of quality, new data sources will be required. Ultimately, a new health information infrastructure, based on uniform data standards and including computerized clinical data systems that are part of the care process, will be necessary. The need to tailor the Quality Report to specific audiences and each year's particular findings makes the task of producing the report more difficult but also optimizes its utility. The obstacles in the path of developing a Quality Report are many, but they are not insurmountable. The recommendations formulated by the committee in this report should help AHRQ make this vision a reality.

Page 17

REFERENCES

. 1998. Quality First: Better Health Care for All Americans. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

, , , , and . Health spending and outcomes: Trends in OECD countries, 1960–1998. 2000. Health Affairs 19(3): 150–157.

. Consumer Price Indexes. [on-line] Available at: http://stats. bls.gov/cpihome.htm [Dec. 5, 2000].

, , and . 1998. The urgent need to improve health care quality: Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. Journal of the American Medical Association 280(11): 1000–1005.

, . 1966. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 44: 166–203.

Foundation for Accountability. 1997. Reporting Quality Information to Consumers. Portland, Ore.: FACCT.

Healthcare Research and Quality Act. 1999. Statutes at Large. Vol. 113, Sec. 1653.

. 1990. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, Vol. 2. ed. Kathleen Lohr. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

. 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. eds. Linda T. Kohn, Janet M. Corrigan, and Molla S. Donaldson. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

and . 1999. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. eds. Maria Hewitt and Joseph V. Simone. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

, , , , , , , and . 2000. Health spending in 1998: Signals of change. Health Affairs 19(1): 124–132.

, , , and . 2000. Commissioned Paper for the Institute of Medicine Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery.

. 2000. The Nation's Report Card: National Assessment of Educational Progress. [on-line] Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/site/home.asp [Dec. 8, 2000].

. 2000. Health, United States, 2000 with Adolescent Health Chartbook, Hyattsville, Md.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

. 2000. The State of Managed Care Quality. Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/about/home.htm.

. 2000. Agenda for Research and Development in Patient Safety. [on-line] Available at: www.npsf.org.

. 2000. NQF: About Us. [on-line] Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/about/home.htm [Dec. 6, 2000].

Page 18

. 1998. Grading the Nation's Report Card: Evaluating NAEP and Transforming the Assessment of Education Progress. eds. James W. Pellegrino, Lee R. Jones, and Karen J. Mitchell. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

. 2000. Grading the Nation's Report Card: Research from the Evaluation of NAEP. eds. Nambury S. Raju, James W. Pellegrino, Meryl W. Bertenthal, Karen J. Mitchell, and Lee R. Jones. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

. 2001. NAEP Reporting Practices: Investigating District-Level and Market-Basket Reporting. Eds. Pasquale J. DeVito and Judith A. Koening. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

, , , , and . 2001. The quality of health care in the United States: A review of articles Since 1987. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Appendix A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

. 1991. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives, Pub. No. (PHS) 91-50212. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

. 2000a. Healthy People 2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

. 2000b. Introduction to the NCVHS [on-line]. Available at: http://ncvhs.hhs.gov/intro.htm [Dec. 22, 2000].