4

Engaging Patients to Improve Science and Value in a Learning Health System

INTRODUCTION

An informed patient, invested in healthcare improvement and engaged in shared decision making, is central to a learning health system. Inherent to this vision is the notion that patients bring unique and important perspectives to health care, as well as the ability to spark improvement; both of which are essential to closing important gaps in health system performance and ensuring that care is effective. Unfortunately, patients, families, and caregivers too often are not engaged as meaningful decision makers in their own care or as partners in health research. This shortcoming has been associated with improvements in the effectiveness, safety, and patient experience of care (Coulter and Ellins, 2007). Given these initial promising results, a key challenge will be to foster the development of a learning culture in health care, in which patients’ contributions to health improvement, clinical research, and their own health decisions are expected and embraced by the health system.

The papers in this chapter explore what is meant—theoretically and practically—by patient engagement in health care, and how health systems might better learn from patient participation to advance clinical science and healthcare delivery as well as better support patients in care and care management decision making. Strategies for improving public awareness of key opportunities for such engagement and for providing tools to enable greater participation also are discussed.

The first paper, by Sharon F. Terry of the Genetic Alliance, offers a vision for the range of contributions patients and the public can make

to improve research. Patient-initiated data collection initiatives, including social networking and information sharing services, have provided important resources for discovery and played a role in better informing patients and investing them in the research enterprise. James Conway of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement explores the potential for greater patient and public engagement to improve health system performance, noting the growing evidence base of how patient engagement could improve a wide array of health and system outcomes, from patient adherence, to clinical outcomes, to financial performance. He proposes a framework to better connect and align the interventions currently under way and encourage and support the development of effective public engagement initiatives. A third paper, by Karen Sepucha of Massachusetts General Hospital, addresses opportunities to better engage patients in treatment decisions through more effective patient–provider communication about patient concerns, expectations, and preferences in order to make shared decision making a routine part of the clinical care encounter.

INVESTING PATIENTS IN THE RESEARCH AND CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT ENTERPRISE

Sharon F. Terry, M.A.

Genetic Alliance

At the center of a learning health system are individuals, families, and communities. As all citizens are eventually members of this stakeholder group, an effective healthcare system must keep this group’s interests paramount. The learning touted as part of the exemplary system must fuel action to transform health care to better serve the needs and interests of individuals, families, and communities, and in essence be accountable and self-correcting. A key component of such a system is a culture that promotes and supports public interest and investment in helping to advance the research enterprise. Although public engagement in health care is often viewed from the narrow perspective of participation in clinical trials, many initiatives currently under way create a very different vision for the range of contributions individuals, families, and communities can make to improve research efforts on the value, science base, and patient experience of health care delivered—from information for basic research to efforts to drive improvements to best practices.

This paper reviews trends in public awareness of and interest in opportunities to contribute to learning about what works in health care, such as improving access to and expanding the use of clinical data, and provides examples of initiatives aimed at supporting patients in these roles. Key lessons learned from current efforts to improve public understanding of the issues

involved and encourage patient contributions to learning in health care are identified, as well as communication strategies that move beyond disease-centric approaches to increase receptivity and insistence by the public with respect to their engagement and investment in the research enterprise.

A Learning Health System

Individuals, families, and communities, while serving as the primary focus of a learning health system, interact with the system in different ways. Collectively, however, these stakeholders value a system that focuses on prevention and wellness, proper diagnosis, and individualized care. An ideal system therefore requires an intelligent blend of savvy stewards and systems that advance the public’s health on the one hand, and on the other, consumer-initiated and/or consumer-driven tools and resources that aggregate and analyze clinical and other health information over time to help enhance understanding of health and disease.

Progress toward this ideal system requires expanding the current concept of a healthcare system to include promoting health, not simply addressing disease. A robust healthcare system must not only include prevention (Frieden, 2010); it must focus on prevention and wellness if the greatest improvements in both health and the system that serves it are to be realized.

Further, the current healthcare system expends a great deal of resources on treatment and not enough on diagnosis, the highest priority for health care according to innovator Clayton Christensen (Christensen et al., 2008; Frieden, 2010). Diagnosis lends a critical granularity to the treatment process, allowing the individualized medicine in which the public is so interested. Although a great deal of attention is given to genetics and genomics as the backbone of personalized or individualized medicine, it is probably more accurate to assume that all of medicine, properly executed, should be individualized, with genetic and genomic information integrated into the individualized plan. The impact will be felt by the diagnosed; the not yet diagnosed, which might be termed the general public; and the public’s health.

Finally, although not an issue at the forefront of public attention, the system needs to be oriented around learning and continuous improvement, or progress toward more efficient and effective health services will continue to be dismally slow.

Beyond Trial Participation:

Enabling Consumer Contributions to Learning and Research

While recognizing the importance of the perspectives of the other system stakeholders, this paper focuses only on the consumer perspective.

The paper highlights efforts of some of the 1,200 disease-specific organizations that make up the Genetic Alliance,1 as well as others, to empower consumers to drive learning in health care. A common perspective of these organizations is that keeping the essence and ultimate mission of their work on the patient will necessarily shorten the distance between discovery and services. When faced with a loved one’s devastating illness, it becomes easier to measure every action and develop a plan to help achieve the ultimate objective of improving the prognosis for a disease.

Clinical trials are an important part of the healthcare system, albeit in the translational rather than the services realm. Best estimates for enrollment in clinical trials for cancer indicate that fewer than 5 percent of adults diagnosed with cancer each year participate in such trials (NCI, 2001). From the National Institutes of Health to the largest pharmaceutical companies, difficulty in enrolling individuals in these trials is of major concern.

At the same time, clinical trials are just one opportunity for consumers to contribute to research and health advancement, and many notable initiatives are beginning to provide a means for consumers to help catalyze the creation of a learning health system through better use of the clinical data and information now being amassed. With these contributions, the system itself will generate hypotheses, not just collect and redisplay data and test hypotheses. The data can talk, and with appropriately balanced privacy and confidentiality protections, individuals and families can communicate to the health information exchange systems in their lives what it is that they value. In this ideal system, the system architecture, the privacy scheme, and the manner in which they assist consumers to cut through a mass of decisions to establish highly granular privacy settings without becoming overwhelmed will be simple (see the section below on consumer health information systems).

Initiatives that provide consumers with control over their data and the opportunity to open access to their data for research have tremendous potential for advancing a consumer-driven culture of research and continuous improvement. However, much more needs to be learned about how to encourage consumers to see the value of such engagement. Several key lessons learned to date are illustrated by the examples provided below.

Biologic Repositories and Clinical Registries

The Genetic Alliance BioBank2 is a biologic repository and clinical registry established in 2003. It was built on the infrastructure of a disease-specific bank established in 1995 for a rare genetic condition called pseudoxanthoma

__________________

1 See http://geneticalliance.org (accessed October 11, 2010).

2 See http://biobank.org (accessed October 11, 2010).

elasticum (PXE). PXE International advised a large number of other disease-specific organizations and determined that the community would be better served with a cost-effective, shared common infrastructure. The community using the BioBank—a number of large and small common and rare disease–specific organizations—brings donors closer to the research enterprise they wish to impact. Researchers using the BioBank can solicit clinical information over time and as needs emerge by making requests to disease-specific organizations (for example, the National Psoriasis Foundation, the Inflammatory Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome Association of America). Thus the gap between research and those waiting for treatment is narrowed. Members of the disease community drive the research through understanding of the day-to-day issues of living with the condition.

Consumer Health Information Systems

Private Access enables individuals to establish granular privacy settings for clinical information that, when properly catalogued, allows researchers to find individuals for specific cohorts. This technology allows individuals to grant “private access” to all or selected portions of their information and thereby determine the information flow with which they are comfortable, mitigating privacy concerns (Lo and Parham, 2010). The controls can be granular down to the data element if desired, enabling individuals to decide whether their genetic, mental health, or any other information they deem sensitive should be shared and if so, with whom. Moreover, the controls are dynamic—anticipating that users will wish to change their settings as their circumstances change and as different needs arise or levels of trust are established. From simple scenarios such as releasing one’s child’s immunization record to a summer camp to making one’s clinical information searchable by selected researchers, this online system provides an important service. It includes a comprehensive audit log and tracking, all consistent with emerging health information technology standards for the coming years. Trusted guides in this system help users establish privacy preferences, which can be difficult to navigate depending on the user’s literacy level.

The healthcare system in the United States (and often abroad as well) can be paternalistic. A highly hierarchical system, with “expert” gatekeepers in the form of physicians, limits the learning that can be accomplished by the system. A system in which all stakeholders play a role and in which consumers are offered the opportunity to help drive learning is much more nimble. The current healthcare system does not allow the kind of consumer engagement needed for a learning health system. Therefore, it is critical to understand how to better guide people to become empowered and informed consumers.

Social Networks and Information Sharing

Consumers are helping to advance learning about health care at a rapid rate through multiple means. An excellent example of the power of consumer participation is PatientsLikeMe®. The founders, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) engineers, describe their endeavor this way: “Our goal is to enable people to share information that can improve the lives of patients diagnosed with life-changing diseases. To make this happen, we’ve created a platform for collecting and sharing real world, outcome-based patient data and are establishing data-sharing partnerships with doctors, pharmaceutical and medical device companies, research organizations, and non-profits.”3 The site allows individuals to aggregate and share their information with one another, and also to choose to share clinical information with pharmaceutical companies. Some may argue that this does not constitute real learning for the biomedical enterprise because some data are self-reported, because individuals’ quality of life is weighted heavily, or because individuals are too involved to maintain the objectivity traditionally sought in clinical research. Moreover, participants and the medical team managing the site are beginning to see trends in the participants’ progression relative to their treatment plans in a far more dynamic and timely manner than is possible with traditional natural history or other clinical trials.

Another example of the power of consumer engagement is Facebook. As of this writing, 520 million members of Facebook from around the world have created 1.2 million health groups on the site. This phenomenon demonstrates an intense interest among people in engaging in some activity around health, and it challenges traditional bricks-and-mortar organizations, in networks such as the Genetic Alliance and the National Health Council, to consider new ways of meeting the needs of consumers. Individuals who once had to make a substantial effort to connect with others around a health issue now find it easy to do so. If 10 years ago one imagined creating a business to sell books from attics and basements throughout the world, this model would have appeared to be unsustainable. Now Amazon and other “long-tail” technologies enable just that. These advances have not yet been incorporated into medicine and health.

Another good example, the Love/Avon Army of Women,4 has attracted more than 300,000 women who do not necessarily have breast cancer, but are simply interested in improving the health of women. Founder Dr. Susan Love started this initiative to provide researchers with a large cohort of healthy women available to take part in research into the causes of breast cancer.

__________________

3 See http://patientslikeme.com (accessed October 11, 2010).

4 See http://www.armyofwomen.org/ (accessed October 11, 2010).

Genetics and Genomics: Advancing Individualized Medicine and Public Health

The explosion of information in genetics and genomics creates a tension between the amount of information available and its interpretation. Consumer-oriented learning in this domain will be essential to the integration of genetics into medicine, and consumer genomics companies are advancing this concept at a rapid rate. There are several such companies, the most commonly referred to being 23andMe, Navigenics, and deCODEme. For example, 23andMe aggregates the data of individuals who pay to have hundreds of thousands of single nucleolide polymorphisms (SNPs) genotyped by the service. These are not primarily individuals with a diagnosis, such as those involved in PatientsLikeMe. The individuals who participate in 23andMe are not seeking a disease community perspective, but instead are interested in genotyping embedded in social networking technologies. 23andMe reports genotypes to individuals, aggregates the scientific literature on those SNPs, and presents representations of an individual’s SNPs compared with interpretations in the current scientific literature and genealogic databases. Individuals can then examine categories called Disease Risk, Carrier Status, Drug Response, and Traits. The company offers genetic counseling and the opportunity to compare one’s genotype with everyone else’s in the database and find potential relatives.

As another example, the company Illumina has created an iPhone application for use with its genome sequencing service. Users can compare their genome with someone else’s and receive updates in the interpretation of that genome on the fly.

Ethicists and regulators have concerns about services provided by these consumer-oriented companies, offering what is often called direct-to-consumer marketing. There is no question that all genetic testing, regardless of the service delivery method, should have appropriate oversight leading to safe and efficacious testing and interpretation. This has been and will continue to be an iterative process for the various systems engaged. Letters sent to several of these companies by the Food and Drug Adminstration5 declare the agency’s determination that the companies must get approval for the testing services they offer. This is a time of dynamic tension between two systems. The more staid, and perhaps antiquated, regulatory system is characterized by great caution and dependence on traditional models of evidence that derive from reliance on traditional experts, and do not allow for the involvement of consumers and the accelerated learning that comes from systems that are able to capture their wisdom. Direct-access testing

__________________

5 See http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm (accessed October 11, 2010).

could be an important catalyst for increasing the learning of the health system in a more dynamic way. In addition, direct-access testing accelerates the examination of social issues and policies around genetic testing and technologies and their delivery.

In considering a learning health system, it is important to include public health. The newborn screening system, probably the nation’s most successful public health program, is an excellent program in which the sharing of information could serve to engage the public in the healthcare system. Most parents do not even know that their child has been screened or that their state has stored the child’s dried residual blood spot. The results have ranged from distrust to lawsuits and destruction of these blood spots. If parents participated in the decision to store blood spots and further, using a dynamic electronic consenting system, consented to levels of use for them, this currently invisible system would enjoy greater support. Integration of the newborns’ screening results with the dried blood spots, dynamic consent for use, and electronic and personal health records can constitute an important learning system for health in the United States. Almost 5 million babies are screened each year, representing 99 percent of the nation’s newborns, so this accomplishment would serve as the basis for a national clinical registry and biological repository system. Efforts such as those of the Genetic Services Branch of the Health Resources and Services Administration and Genetic Alliance’s Newborn Screening Clearinghouse give parents and providers ways of interacting with the system so it can learn from the engagement.

Another federally funded effort, the Genetics for Early Disease Detection and Intervention to Improve Health Outcomes (GEDDI) program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is also capturing learning in the system to accelerate the usefulness of genomic applications. Understanding that there is far too much information for any clinician to digest in making decisions about the use of genetic and genomic tests, GEDDI is building a knowledge base and using the public participation tool Google Knol to create a body of expert-moderated knowledge that will allow correlations to be drawn and affirmed more quickly than is typical in more traditional models. Ultimately the program is asking when and where genetics can be used for early detection, and answering this question will require consumer participation in the process of understanding what brings value not only for the individual, but also for communities and ultimately the public’s health on a large scale.

Concluding Observations

The activities described in this paper reveal that there is a long way to go in developing the policies necessary to encourage and support patients

becoming invested in the research and continuous improvement enterprise of a learning health system. However, they also indicate an increasing interest among the general public in participating in health care—rather than just being spectators, and given the acceleration of consumer-driven advances in other fields—such as the computer industry, health care will accelerate its learning with increased consumer participation. Indeed, data from the Genetics and Public Policy Center indicate that individuals would like to participate in large data collection efforts in the United States and would like to receive individual results (Kaufman et al., 2008). When individuals in these surveys and town halls were asked whether they would participate if they did not receive individual results, 75 percent said they would be less likely to participate. Regardless of one’s opinion on sharing results, such data indicate that the public would like to participate and learn.

A learning health system is not just a laudable goal but is essential for the health of the nation. At present, we are dependent on antiquated systems that rely on hierarchical gatekeeping. Phenomenal advances have been made in many areas of technology that can support social services. Health care lags behind other domains in its ability to capitalize on the learning available to it. Ultimately, the problem may lie in “knowledge turns,” a term to describe “how well we transform raw ideas into finished products and services” (Savage, 2010). Knowledge turn rates describe many kinds of transactions in this information age. Disruptive insertion of consumers into the equation will ultimately generate faster knowledge turns and accelerate the learning of the health system.

PUBLIC AND PATIENT STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE HEALTH SYSTEM PERFORMANCE

James B. Conway, M.S., M.A.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

The charter of the IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care underscores the centrality of the patient. The summary of the Learning Healthcare System workshop refers to both the need for a culture of shared responsibility that includes patients, providers, and researchers and the need for improved communication around the nature of public engagement (IOM, 2007). Widespread federal, state, public, and private position and policy statements, as well as those from healthcare industry leaders, speak to the importance of engagement of the patient, family, public, and community (Berwick, 2009). Excitement about public engagement grows daily, driven as much by financial constraints as by the synergy of engagement and improvements in population health and the healthcare experience. This excitement is being fueled by early successes in communities, organizations,

and microsystems and in the direct experience of care, as well as by the increasingly widespread view that members of the public must “do their part to improve outcomes and reduce cost” (AHA, 2004; Frampton et al., 2008; IHI, 2009; Johnson et al., 2007).

Yet there exists no widely embraced framework defining patient (consumer, public, family) engagement. Conversations about its meaning elicit differing views, typically focused on one discrete aspect of the issue. Opinions of health professionals about what the public “wants” or “needs to do” are often at odds with research findings on these issues. The need for and potential power of an overarching framework for public engagement is apparent. With such a framework, the various interventions (threads) of experimentation, research, and innovation could be connected for design, measurement, assessment, and improvement purposes.

This paper briefly examines the current state of public engagement, including shortfalls, definitions, opportunities, and evidence; presents a framework for public engagement; and provides a focused charge for moving forward.

Shortfalls in Public Engagement

In the midst of exceptional care, caring, hope, and discovery, there is extraordinary suffering, harm, tragedy, waste, and inefficiency in the healthcare system (IOM, 1999, 2001). Prevention and wellness are losing out to failures in the patient experience and population health—failures such as harm, obesity, and poorly managed chronic care. Care coordination fails both at the system level and for the individual. If it is organized for anyone, the care system is built around those who deliver care, not those who receive it. Enormous national resources produce comparatively poor health outcomes.

There is a growing realization that until the healthcare system is organized around the patient and the public, it will not be transformed as it needs to be. The Lucian Leape Institute of the National Patient Safety Foundation presents five transforming concepts for health care, one of which is that the public must become full partners in all aspects of health care. The Institute believes, “if health or health care is on the table, the patient/consumer must be at the table, every table. Now” (Leape et al., 2009). Likewise, the National Priorities Partnership of the National Quality Forum includes patient and family engagement as one of the six overarching priorities of a transformed U.S. healthcare system (NPP, 2010).

Definitions of Patient Engagement

There are many descriptions and definitions of the attributes of patient engagement and participation. Three are presented here.

The IOM defines patient-centered care as care based on continuous healing relationships; care that is customized according to patient needs and values; care where the patient is the source of control; care where knowledge is shared and information flows freely; and care where transparency is necessary and where the patient’s needs are anticipated (IOM, 2001).

The Institute for Family Centered Care (Institute for Family-Centered Care, 2008) offers four key concepts for patient- and family-centered care, all with a focus on collaboration:

- Dignity and respect—Providers listen and honor patient and family perspectives and choices.

- Information sharing—Providers share complete and unbiased information in ways that are affirming and useful.

- Participation—Patients and families participate in care and decision making.

- Collaboration—Patients and families collaborate in policy and program development, implementation, and evaluation, as well as the delivery of care.

Finally, according to the National Quality Forum’s National Priorities, patient- and family-centered care is health care that honors each individual patient and family, offering voice, control, choice, skills in self-care, and total transparency, and that can and does adapt readily to individual and family circumstances, and to differing cultures, languages, and social backgrounds (NPP, 2010).

Striking in all of these definitions is the importance of control and shared ownership—a clear sense of “we.” The aim is collaboration all the time, not just when it is convenient. In the words of the Saltzberg Seminar, “Nothing about me, without me” (Delbanco et al., 2001).

Opportunities: One View of What Is Possible

Decades of work demonstrate the powerful opportunities created by public engagement. At Children’s Hospital in Boston in the 1970s, mothers began to tell leaders and staff, “I don’t care who you are, I’m staying with my child overnight.” Leaders learned that “there is no force in the world stronger than a mother in their face advocating for her child.” In a dispute between the hospital’s record and the mother’s record, one should believe the mother’s—the only person taking care of the whole child. In 1996, leaders at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute invited patients and family members to populate all decision-making structures and processes in the organization (Ponte et al., 2003). In both organizations, after parents, patients, and family members were invited into groups working on hospital design,

care system design and delivery, visiting hours, resource centers, and much more, the enormous power of engagement began to appear. Patients and families were the only ones in the room who actually experienced care. Leaders also learned that while they often ask people what they want, they often fail to listen long enough to hear the answer. When leaders listen, the public, the patient, and the family can teach and tell them things they never knew. Healthcare systems, delivery, care, and outcomes are better as a result (Popper et al., 1987).

During the period 2005–2006, the IOM Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors examined organizing the medication system around the patient and those who care for the patient (IOM, 2006). For the committee members, when the lens was through the patient, the enormous power and complexity of such an effort was clear.

In two communities in Massachusetts, a grassroots effort has been under way for almost 2 years to encourage the public to participate more actively in their own care. The Partnership for Healthcare Excellence6 is seeing and measuring important improvements in understanding of key healthcare themes in this study. Learning has focused on the ability to engage communities (public, healthcare, civic agencies) around common themes and the strength of simple and positive messages, such as “smart patients ask questions,” “wash your hands,” and “carry a medication list.”

Finally, two Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) initiatives provide further insight and illustration. A collaborative project among IHI, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Institute for Family Centered Care, called New Health Partnerships,7 produced a program on self-management. New practices and improved outcomes associated with shared care planning were apparent. In the IHI Get Boards on Board initiative, part of the 5 Million Lives Campaign, key content has focused on encouraging governance and executive leadership to seek out opportunities to meet patients and families in several contexts: at the sharp end of error, through rounding, in ad hoc invitations to participate in improvement, in the community, or through patient and family advisory councils. Across the nation, energized boards and executive leadership speak to the power of the experience: “It’s the first time I saw our organization through the eyes of the patient.” It is also sobering to routinely hear the question, “How do I talk with patients?” (Conway, 2008).

These are just a few of the many thousands of engagement initiatives under way across the country. From these and other experiences many themes emerge. Two are of particular note. The first is most sobering: “If only we had listened.” If staff and leaders had stopped, listened, and en-

__________________

6 See http://www.partnershipforhealthcare.org (accessed October 11, 2010).

7 See http://www.newhealthpartnership.org (accessed October 11, 2010).

gaged with patients and families, healthcare systems could be dramatically better; for many family members, their loved one might not have suffered harm or death. The second theme is that engaging patients, families, and the public leads to better outcomes for everyone.

Evidence of the Impact of Public Engagement

For many, public engagement is seen as “nice but not necessary,” “the soft stuff”—“if only they did what they were told.” Yet growing research reveals the impact patient engagement can have on health outcomes, patient adherence, process-of-care measures, clinical outcomes, business outcomes, patient loyalty, reduced malpractice risk, employee satisfaction, and financial performance—including reduced lengths of stay, lower cost per case, decreased adverse events, higher employee retention rates, reduced operating costs, decreased malpractice claims, and increased market share (Charmel and Frampton, 2008; Edgman-Levitan and Shaller, 2003; Stewart et al., 2000). A literature review conducted by IHI in 2009 identified extensive findings on public engagement, with a particular focus on care of the hospitalized patient (IHI, 2009). A recent review by the Picker Institute, Invest in Engagement, presents much more evidence and further exemplars across the breadth of engagement.8

A Framework for Public Engagement

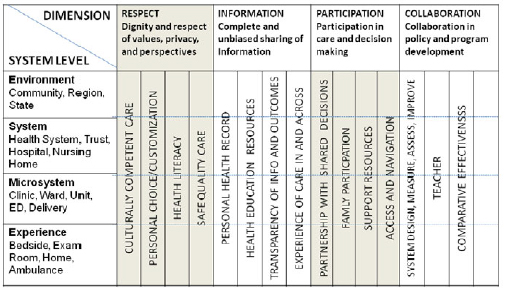

As noted, no comprehensive framework currently exists for engaging patients and families and the public. There are many interventions, but connections among them are loose or nonexistent. In 2002, Donald Berwick introduced the notion of the “chain of effect for quality,” proposing that it will take integrated change at four levels to achieve the goals of the IOM’s Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001): environment, organization/system, microsystem, and the care experience (Berwick, 2001). Applying that thinking in the context of current examples, a rudimentary organizing approach for all of the activities in public engagement emerges (Table 4-1).

Yet something remains missing. Although each of these activities in its own right adds to understanding and improvement, collectively they could be far more powerful if built across levels on common threads or principles. For example, advanced care planning, access to the hospital chart, access to help and care around the clock, honoring patient wishes, and experience surveys achieve their real potential only if the activities at one level (environment, organization, microsystem, experience of care) are reinforced at the other three levels.

__________________

8 See http://www.investinengagement.info/ (accessed February 9, 2011).

TABLE 4-1 An Organizing Approach for Public Engagement

|

|

||

| Location | Examples | |

|

|

||

| Environment | Community, Region, State | Community groups Care Coordination, ACOs, Medical Homes Advanced care planning, POLST, MOLST School & church programs Public health & other consumer campaigns |

|

Organization |

Health System, Trust, Hospital, Nursing Home |

Experience Surveys P&F councils, Advisors, Faculty Resource centers, patient portals Access to help and care 24/7 Medication lists |

|

Micro-system |

Clinic, Ward, Unit, ED, Delivery |

Parent, advisors, & advisory councils Open access, optimized flow Family participation in rounding |

|

Experience of care |

Bedside, Exam Room, Home |

Access to the chart Shared care planning “Smart Patients Ask Questions” |

|

|

||

NOTE: ACOs = Accountable Care Organizations; MOLST = Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment; POLST = Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment.

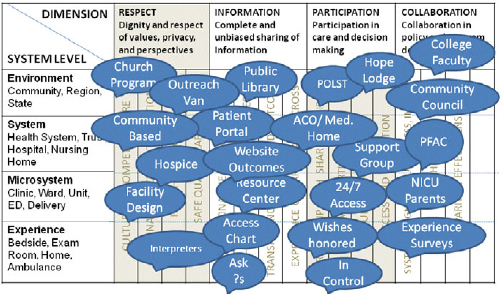

Figure 4-1 plots these four levels against the elements of the Institute for Family Centered Care’s definition of patient- and family-centered care. Further threads of these elements are detailed under each that cut across all levels. Each of the examples in Table 4-1 could then be layered on at the appropriate intersections of Figure 4-1 to produce Figure 4-2. Although these graphics are only a beginning, the possibilities emerge for aligning, building, connecting, and evaluating. Informing this work will be advanced models of thinking in other countries where population health, care transitions, and community already have a much stronger role in health and health care than they do in the United States today.

Moving Forward

In a study of patient/public engagement in Europe, Groen and colleagues (2009) note, “The widespread implementation of policies to ensure patients’ rights, privacy, and confidentiality is noteworthy. Patient involvement in quality improvement activities, on the other hand, so far appears to be more a rhetorical exercise than a practice.” The same is the case for the United States. What is needed to advance that agenda rapidly is clarity of expectation: if health care is on the table, the public is at the table,

every table; visionary leadership, experimentation, and innovation are rewarded and incentivized; model frameworks for public engagement are introduced; and the evidence base is disseminated and enhanced.

Finally, making patient engagement personal is essential to connect the heart as well as the mind. The effort is about the care for everyone, for family and friends as well as for the communities the system is privileged to serve.

COMMUNICATING WITH PATIENTS ABOUT THEIR CONCERNS, EXPECTATIONS, AND PREFERENCES

Karen Sepucha, Ph.D.

Massachusetts General Hospital

Should I take this medication? Should I skip that screening test? Should I tell my doctor about these new symptoms? Patients and providers need to communicate in order to determine appropriate courses of action across a range of health issues. A high-quality decision on testing or treatment requires communication about the options and the potential good and bad outcomes, as well as consideration of patients’ concerns, goals, expectations, and preferences for those outcomes. This paper highlights gaps in the quality of medical decisions made in the United States, describes interventions that have been shown to improve the quality of decisions, and reviews some promising approaches to putting these interventions into practice.

The Quality of Medical Decisions in the United States

Some situations in medicine are fairly straightforward; there is a clear diagnosis and a single best treatment or approach. This is the case when there is considerable evidence of benefit with little evidence of harm. These situations have been referred to as “effective care,” and communication with patients has focused on convincing them to implement the proven approach (Wennberg et al., 2007). Yet a surprising number of clinical situations are not examples of effective care. Instead of one approach, there are multiple options. Instead of clear evidence of benefit, there are limited or low-quality data on efficacy. Instead of benefits clearly outweighing harms, there are difficult trade-offs to be made. These kinds of situations are referred to as “preference-sensitive” situations (Wennberg et al., 2007). In such cases, the “best” option is determined not only by the medical evidence but also by patients’ individual views. Many common medical decisions, such as the treatment of lower back pain, osteoarthritis, breast and prostate cancers, and benign prostate and benign uterine conditions, are considered preference-sensitive situations.

Preference-sensitive situations are not easy for patients or providers. The burden of decision making is now added to the burden of illness. The

decision making is complicated because neither patient nor provider can do it well alone. The patient needs the medical expertise of the provider, which includes evidence about the options and the potential good and bad outcomes. The physician needs the patient’s self-knowledge, which includes the meaning of the illness and the potential treatments in the patient’s life, as well as the patient’s motivation and confidence to implement the different options. This information needs to be shared and then used to select the option that will best meet the patient’s goals and needs (Charles et al., 1999; Mulley, 1989). This interactive process has been termed “shared decision making” and is necessary to ensure that patients get the treatment they need and no less, and the treatment they want and no more (Science Panel on Interactive Communication and Health, 1999).

How close is clinical practice to achieving a shared decision-making process? The DECISIONS study provides some evidence for the quality of common decisions across the United States. A nationally representative telephone survey interviewed 3,010 adults about nine common medical decisions on elective surgery (for back pain, knee/hip osteoarthritis, and cataracts), cancer screening (for breast, colon, and prostate cancers), and medication (for high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and depression). Respondents reported on their involvement in the decision, their knowledge of four to five key facts related to the decision, and their goals and concerns (Zikmund-Fisher et al., 2010).

The key findings of the study raise questions about the quality of medical decisions and the amount of shared decision making in the United States today. For the most part, respondents had very little knowledge about the options available to them and the likely consequences of those options. For seven of nine conditions, fewer than half of the respondents could answer more than one knowledge question correctly (Fagerlin et al., 2010). For example, only 17 percent of respondents who reported making a decision about taking cholesterol medication could correctly identify its most common side effect. Most men who had made a decision about screening for prostate cancer vastly overestimated the likelihood of dying of the disease, believing the risk was 20 percent as opposed to the actual likelihood of approximately 3 percent (Fagerlin et al., 2010). In other words, there is substantial evidence that patients are not making informed decisions.

Shared decision making requires meaningful discussion among providers and patients about treatment options, including both pros and cons. Respondents in the DECISIONS study were much more likely to report that their providers discussed the reasons for undergoing a treatment or test compared with the reasons for not doing so. In fact, respondents reported discussing both the pros and cons less than half the time (Zikmund-Fisher et al., 2010). Shared decision making also requires discussion of what is most important to patients. Respondents reported that providers asked them what they wanted only about half the time. This result varied by

situation and ranged from 33 to 50 percent for cancer testing decisions to 64 to 80 percent for surgery decisions (Zikmund-Fisher et al., 2010). The data suggest that communication about patients’ concerns and preferences is variable, and often lacking.

Implications and Opportunities for Improvement

Not sharing accurate, complete information about options and likely outcomes can lead to patients receiving the wrong treatment. Not asking patients what is most important to them and using that information to guide treatments also leads to patients receiving the wrong treatment. How often does this happen? In a subset analysis of the Cochrane Collaborative systematic review of decision aids focusing on decisions aids for elective surgery, informed patients were 25 percent less likely to choose surgery compared with controls (O’Connor et al., 2007a). That finding suggests that one in four patients going to the operating room may be receiving the wrong treatment—surgery they would not have chosen if they had been informed and if providers had listened to them. The patient safety and resource implications of these findings are significant.

How can these gaps in the quality of decisions be filled? Three main approaches have been used to promote shared decision making—provider training, patient coaching and question checklists, and patient decision aids.

Provider Training

Provider training focuses on teaching communication skills and decision coaching skills (for example, risk communication) using a variety of teaching methods. Coulter and Ellins (2006) summarize results from several systematic reviews of provider training in communication skills and conclude that most training programs have a positive impact on both provider communication behaviors and patients’ knowledge and satisfaction. However, there was mixed evidence of an impact on patient health outcomes and utilization of services (e.g., a positive impact on medication adherence but no impact on diabetes outcomes) (Coulter and Ellins, 2006).

Patient Coaching and Question Checklists

Patient coaching and question checklists, typically administered in advance of the visit, are designed to help patients communicate with providers and may promote shared decision making. A Cochrane systematic review of 33 randomized controlled trials of these interventions found that they produced a modest impact on patient outcomes (Kinnersley et al., 2007). In the Cochrane meta-analysis, the interventions were shown to increase

the number of questions patients asked, as well as patient satisfaction. The meta-analysis did not find a statistically significant change in patient anxiety or knowledge or in length of consultation.

Patient Decision Aids

Decision aids are tools that provide balanced information on options and outcomes and help patients think through their values and what is most important to them before making a decision. The International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration is an international group of researchers, clinicians, consumers, and policy makers created to set standards for the development, organization, and content of decision aids (Elwyn et al., 2006). The tools are available in a variety of media, and researchers at the University of Ottawa maintain a library of decision aids that is available online (OHRI, 2010).

There have been more than 55 randomized controlled trials of patient decision aids. A Cochrane systematic review of these studies found that these tools increase patients’ knowledge, the accuracy of their risk perceptions, and their desire to participate in decisions (O’Connor et al., 2007a). The tools also help those who are undecided to make a choice, and to do so without increasing anxiety. As mentioned earlier, subgroup analysis of trials comparing elective surgery with nonsurgical options found a 25 percent decrease in use of surgery for those exposed to a decision aid. Of course, the goal of decision aids is not to increase or decrease utilization, but to increase the proportion of patients who are matched to the right treatment for them.

Many decision aids are widely available, although their use is not common. A few organizations and researchers have made significant, sustained investments in developing and disseminating patient decision aids. Three companies that have developed many of these tools are Healthwise, Inc., Health Dialog, Inc., and the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. Researchers at Ottawa Health Research Institute, McMaster University, and the University of Wisconsin have also developed patient decision aids. Commercial entities disseminate decision support via a health coaching model implemented through a call center at the health plan level (e.g., Health Dialog) and Internet-based models that deliver decision aids directly to consumers (e.g., Healthwise via WebMD) (O’Connor et al., 2007b).

Experience with the implementation of decision aids at the provider level in the United States is coming largely from demonstration projects and learning collaboratives, several of which are funded by the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. The Breast Cancer Initiative has found significant interest in and sustained use of breast cancer deci-

sions aids among both community and academic cancer centers (Silvia et al., 2008). Massachusetts General Hospital has launched an “ePrescribe” project that gives primary care physicians the capability to prescribe decision aids electronically. Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) has integrated decision aids into primary and specialty care and seen significant success in their ability to reach patients. The use of decision aids at DHMC has resulted in improved patient knowledge and increased ability to tailor treatments to patients’ goals (Collins et al., 2009).

Shared Decision Making and Clinical Practice

What is needed to support patients and providers in making the changes required to integrate shared decision making into routine clinical care? Repeatedly it has been shown that organizational change seldom occurs unless the desired performance is routinely measured. This suggests that if there were a way to document the gaps between routine care and the knowledge-based and patient-centered ideal, it might stimulate changes in provider and patient behavior.

Systematically documenting the large gaps in decision quality could generate significant demand for tools and approaches such as decision aids (Sepucha et al., 2004). This documentation would require rigorous and practical survey instruments that could capture the gaps in patients’ understanding and highlight the numerous instances in which patients received care they did not want or need (Sepucha et al., 2004). Fostering competition among hospitals and practices in how well they inform their patients and how attentive they are to their patients’ preferences could lead to substantial improvements in the quality of health care. In fact, the recent healthcare reform legislation calls for the development of quality measures, including those focused on decision quality, as well as for the development of certification for decision aids and other tools designed to promote shared decision making.

Conclusion

In summary, the data show much variability in the quality of medical decisions. Too often patients are not meaningfully involved or well informed, and their goals and concerns are not taken into account. Decision aids are effective tools that promote shared decision making and have been integrated successfully into routine clinical care. Shared decision making, which requires productive communication between healthcare providers and patients about the evidence and their concerns and preferences, is a critical foundation for a learning health system.

REFERENCES

AHA (American Hospital Association). 2004. Strategies for leadership: Patient and family-centered care. http://www.aha.org/aha/issues/Quality-and-Patient-Safety/strategies-patientcentered.html (accessed June 10, 2010).

Berwick, D. 2001. A user’s manual for the IOM’s “Quality Chasm” report. Health Affairs 21(3):80-90.

Berwick, D. M. 2009. What “patient-centered” should mean: Confessions of an extremist. Health Affairs (Millwood) 28(4):w555-w565.

Charles, C., A. Gafni, and T. Whelan. 1999. Decision-making in the patient-physician encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science & Medicine 49:651-661.

Charmel, P., and S. Frampton. 2008. Building the business case for patient centered care. Heath Care Financial Management 62(3):80-85.

Christensen, C. M., J. H. Grossman, and J. Hwang. 2008. The innovator’s prescription: A disruptive solution for health care. First ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Collins, E. D., C. P. Moore, K. F. Clay, S. A. Kearing, A. M. O’Connor, H. A. Llewellyn-Thomas, R. J. Barth, and K. R. Sepucha. 2009. Can women with early-stage breast cancer make an informed decision for mastectomy? Journal of Clinical Oncology 27(4):519-525.

Conway, J. 2008. Getting boards on board: Engaging governing boards in quality and safety. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 34(4):214-220.

Coulter, A., and J. Ellins. 2006. Patient-focused interventions: A review of the evidence. http://www.health.org.uk/publications/research_reports/patientfocused.html (accessed June 11, 2010).

———. 2007. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 335(7609):24-27.

Delbanco, T., D. Berwick, J. Boufford, S. Edgman-Levitan, G. Ollenschläger, D. Plamping, and R. Rockefeller. 2001. Healthcare in a land called peoplepower: Nothing about me without me. Healthcare Expectations 4:144-150.

Edgman-Levitan, S., and D. Shaller. 2003. The CAHPS® improvement guide: Practical strategies for improving the patient care experience. Cambridge, MA: Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School.

Elwyn, G., A. O’Connor, D. Stacey, R. Volk, A. Edwards, A. Coulter, R. Thomson, A. Barratt, M. Barry, S. Bernstein, P. Butow, A. Clarke, V. Entwistle, D. Feldman-Stewart, M. Holmes-Rovner, H. Llewellyn-Thomas, N. Moumjid, A. Mulley, C. Ruland, K. Sepucha, A. Sykes, and T. Whelan. 2006. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: Online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 333(7565):417.

Fagerlin, A., K. R. Sepucha, M. P. Couper, C. A. Levin, E. Singer, and B. J. Zikmund-Fisher. 2010. Patients knowledge about 9 common health conditions: The DECISIONS survey. Medical Decision Making 30(5 suppl):35S-52S.

Frampton, S., S. Guastello, and C. Brady. 2008. Patient-centered care: Improvement guide. Derby, CT; Camden, ME: Planetree Picker Institute.

Frieden, T. 2010. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health 100(4):590-595.

Groene, O., M. Lombarts, N. Klazinga, J. Alonso, A. Thompson, and R. Sunol. 2009. Is patient-centredness in European hospitals related to existing quality improvement strategies? Analysis of a cross-sectional survey Quality and Safety in Health Care 1:44-50.

IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement). 2009. Improving the patient experience of inpatient patient care. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientCenteredCare/PatientCenteredCareGeneral/EmergingContent/ImprovingthePatientExperienceofInpatientCare.htm (accessed June 10, 2010).

Institute for Family-Centered Care. 2008. Advancing the practice of patient- and family-centered care: How to get started. http://www.familycenteredcare.org/pdf/getting_started.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1999. To err is human. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2006. Preventing medication errors: Quality chasm series. Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2007. The learning healthcare system: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson, B., M. Abraham, J. Conway, L. Simmons, S. Edgman-Levitan, P. Sodomka, J. Schlucter, and D. Ford. 2007. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient and family-centered health care system: Recommendations and promising practices. http://www.familycenteredcare.org/pdf/PartneringwithPatientsandFamilies.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010).

Kaufman, D., J. Murphy, J. Scott, and K. Hudson. 2008. Subjects matter: A survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genetics in Medicine 10(11):831-839.

Kinnersley, P., A. Edwards, K. Hood, N. Cadbury, R. Ryan, H. Prout, D. Owen, F. MacBeth, P. Butow, and C. Butler. 2007. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 3(3).

Leape, L., D. Berwick, C. Clancy, J. Conway, P. Gluck, J. Guest, D. Lawrence, J. Morath, D. O’Leary, P. O’Neill, D. Pinakiewicz, and T. Isaac. 2009. Transforming healthcare: A safety imperative. Quality and Safety in Health Care 18(6):424-428.

Lo, B., and L. Parham. 2010. The impact of Web 2.0 on the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38(1):17-26.

Mulley, A. 1989. Assessing patients’ utilities: Can the ends justify the means? Medical Care 27(3):S269-S281.

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2001. Doctors, patients face different barriers to clinical trials. http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/conducting/developments/doctors-barriers0401 (accessed October 11, 2010).

NPP (National Priorities Partnership). 2010. Patient and family engagement. http://www.nationalprioritiespartnership.org/PriorityDetails.aspx?id=596 (accessed February 18, 2011).

O’Connor, A. M., D. Stacey, M. J. Barry, N. F. Col, K. B. Eden, V. Entwistle, V. Fiset, M. Holmes-Rovner, S. Khangura, H. Llewellyn-Thomas, and D. R. Rovner. 2007a. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Decision Making 27(5):554-574.

O’Connor, A. M., J. E. Wennberg, F. Legare, H. A. Llewellyn-Thomas, B. W. Moulton, K. R. Sepucha, A. G. Sodano, and J. S. King. 2007b. Toward the “tipping point”: Decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Affairs 26(3):716-725.

OHRI (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute). 2010. Decision aid library inventory. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/cochinvent.php (accessed 2010, October 12).

Ponte, P., G. Conlin, J. Conway, and et al. 2003. Making patient-centered care come alive: Achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. Journal of Nursing Administration 33(2):82-90.

Popper, B., B. Anderson, A. Black, E. Ericson, and D. Peck. 1987. A case study of the impact of a parent advisory committee on hospital design and policy, Boston Children’s Hospital. Children’s Environments Quarterly 4(3):12-17.

Savage, C. M. 2010. Knowledge turns. http://www.kee-inc.com/kturns.htm (accessed June 1, 2010).

Science Panel on Interactive Communication and Health. 1999. Wired for health and well-being: The emergence of interactive health communication. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Sepucha, K., F. J. Fowler, and A. J. Mulley. 2004. Policy support for patient-centered care: The need for measurable improvements in decision quality. Health Affairs Suppl Web Exclusives:VAR54-62.

Silvia, K., E. Ozanne, and K. Sepucha. 2008. Implementing breast cancer decision aids in community sites: Barriers and resources. Health Expectations 11(1):46-53.

Stewart, M., J. B. Brown, A. Donner, I. R. McWhinney, J. Oates, W. W. Weston, and J. Jordan. 2000. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. Journal of Family Practice 49(9):796-804.

Wennberg, J., A. O’Connor, E. Collins, and J. Weinstein. 2007. Extending the p4p agenda, part 1: How Medicare can improve patient decision making and reduce unnecessary care. Health Affairs 26(6):1564-1574.

Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., M. P. Couper, E. Singer, C. A. Levin, F. J. Fowler, S. Ziniel, P. A. Ubel, and A. Fagerlin. 2010. The DECISIONS study: A nationwide survey of United States adults regarding 9 common medical decisions. Medical Decision Making 30(5 suppl):20S-34S.