Carter H. Strickland, Jr.1

and

Christopher M. Hawkins

New York City Department of Environmental Protection

ABSTRACT

Viable solutions for more livable cities of the future must consider three pillars of sustainability: the public’s quality of life, the environment, and the economy. On Earth Day, April 22, 2007, New York City released PlaNYC, its far-reaching sustainability plan to prepare the city for significant population growth, strengthen its economy, address climate change, and enhance quality of life for the city’s residents. Updated in 2011, PlaNYC has 132 initiatives and more than 400 specific milestones that bring together more than 25 city agencies to work toward a greener, greater New York. This comprehensive plan has provided compelling justification for investing in infrastructure at a time when many government entities have cut back on spending to meet short-term needs.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection plays a key role in more than a quarter of the plan’s initiatives, creating innovative and sustainable source water protection techniques to maintain high-quality drinking water; using green infrastructure, such as artificial wetlands, blue

___________________

1 This paper was presented at the symposium by Christopher M. Hawkins, chief of staff, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, on behalf of Carter H. Strickland, Jr. The symposium preceded Hurricane Sandy and therefore did not cover that important event or the city’s response, including the June 2012 plan titled A Stronger, More Resilient New York for addressing the impacts of climate change.

roofs, and bioswales, to manage stormwater and provide other sustainability benefits to the city; developing alternative and distributed generation technologies at wastewater treatment plants; and improving the city’s air quality by supporting the transition to cleaner heating oil and updating the Air Code.

INTRODUCTION

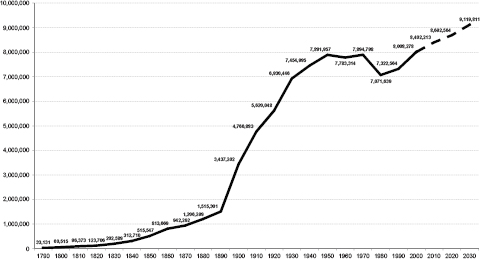

In 2006 there were approximately 8 million people in New York City and the population was expected to grow to approximately 9 million by 2030 (Figure 1), raising questions of how to meet the complex challenges to accommodate an additional 1 million people while continuing to improve the quality of life for New Yorkers.

To address these and other emerging challenges associated with the city’s growth, Dan Doctoroff, then deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, formed the Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS), which brought together multiple city agencies and stakeholders to create the long-term vision for the city. In 2006 the city formed a Sustainability Advisory Board of local elected officials and local and national experts with backgrounds in environmental justice, green buildings, environmental policy, real estate, business, labor, energy, and urban planning. The board

FIGURE 1 Historic and Projected Population of New York City, 1790–2030. Source: NYC Department of City Planning.

and subsequent outreach generated more than 5,000 comments that helped shape PlaNYC and served to facilitate and synthesize public engagement.

To determine the impact of climate change on New York City, the mayor’s office also created the New York City Panel on Climate Change (PCC), composed of leading climate change scientists and legal, insurance, and risk management experts, which came out with findings in 2009. In a similar fashion, initiatives to address energy efficiency in buildings, local air pollution, traffic congestion, and other topics were developed through careful factual analysis, followed by extensive economic cost-benefit analysis and stakeholder consultation to arrive at policy proposals that prioritized practical results. Annual progress reports, supplementing existing accountability mechanisms, support accountability for achieving the goals of the plan and advancing each of the 132 initiatives.

First published in 2007, PlaNYC is required by law to be updated every four years. The latest iteration, released in 2011, is divided into ten subject areas.2 More than a quarter of the initiatives in the plan are led by the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), including those related to water supply, harbor water quality, and air quality. The remainder of this paper provides a summary of the subject areas and initiatives relevant to DEP and the department’s progress since the release of the 2007 version of PlaNYC.

DRINKING WATER

Ensuring a livable city requires a high-quality, reliable water supply. Since the 17th century when the first Dutch settlers began to colonize the islands, New York City has prioritized the search for ever more plentiful and reliable sources of water to fight fires, improve sanitation and public health, and accommodate a growing population. Today, the city’s 2,000-square-mile watershed contains 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes, and water is delivered from more than 125 miles away. The city also performs more than 500,000 water quality tests each year to ensure that our drinking water is safe and meets federal standards.

___________________

2 One significant topic added was solid waste management and recycling, which had been left out of the 2007 plan because the city had published a standalone Solid Waste Management Plan in 2006 after a decade of discussion and dispute following the closure of Fresh Kills Landfill in 1996.

Watershed Protection

To maintain high-quality drinking water, the city has continued to invest in a robust watershed protection program. Since 1993, the federal government has deemed that New York City’s watershed and drinking water are of high enough quality that it has permitted the city to supply unfiltered drinking water, making it just one of five major cities in the country with this privilege.

Much of the land in the watershed is rural and composed of family farms and forestlands. Since 1997, the city has acquired more than 130,000 acres of land in high-priority areas that are most likely to benefit the city’s water supply. To balance watershed protection with the interests and economic vitality of watershed communities, the city has avoided acquisitions in and around towns that have designated such properties as important for their future growth while maintaining watershed protection rules that reduce or eliminate sources of pollution. The city has also worked with the Watershed Agriculture Council to help more than 350 farms develop and implement Whole Farm Plans that protect water quality from agricultural pollutants and benefit farmers as well.

These investments have helped New York City maintain its ability to provide unfiltered drinking water and eliminated the need to build a multibillion-dollar water filtration plant, while keeping the city’s drinking water clean, reliable, and affordable.

Water Delivery and Treatment

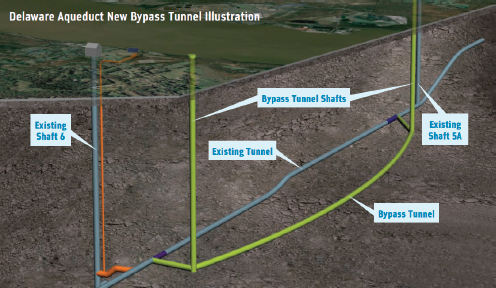

The city continues to invest in the critical infrastructure that delivers more than 1 billion gallons of water per day to more than 9 million New Yorkers.3 The Delaware and Catskill Aqueducts currently deliver all of the city’s drinking water to the in-city distribution system. Since the 1990s, DEP has been monitoring significant leaks in a portion of the Delaware Aqueduct that connects the Rondout Reservoir in Ulster County to the West Branch Reservoir in Putnam County. To overcome the great challenge of these leaks, DEP will build a $1.4 billion 3-mile bypass tunnel around a portion of the aqueduct (Figure 2), running east from the town of Newburgh in Orange County, under the Hudson River to the town of Wappinger in Dutchess County, on the east side of the Hudson. Under the plan, DEP will break ground on the

___________________

3 This number includes upstate residents in addition to New York City’s population of 8.3 million.

FIGURE 2 Illustration of the Delaware Aqueduct Bypass Tunnel

bypass tunnel in 2013 and complete the connection to the Delaware Aqueduct in 2019.

Despite the city’s extensive history of protecting public health, under the Safe Water Drinking Act the federal government has mandated that the city complete two major water treatment facilities, the Catskill/Delaware Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility and the Croton Water Filtration Plant. In 2008, the city began construction on the $1.6 billion Catskill/Delaware Facility to comply with a federal mandate that requires treatment of surface-level drinking water supplies with two sources of disinfection—in our case, chlorine and ultraviolet light. In October 2012, the city began treating all tap water at the plant and will complete construction in 2013.

The Croton Watershed was first tapped to supply drinking water in 1840. Today this watershed is highly developed and, although the water supply meets all health-based water quality standards, there have been seasonal complaints about color, odor, and taste. In 2007, the city began construction on the $3.2 billion Croton Water Filtration Plant in the Bronx. The city completed two water tunnels linking the plant to the New Croton Aqueduct in February 2011 and expects to begin operating the plant by the end of 2013.

WATERWAYS

New York City’s five boroughs are situated on an archipelago and together account for more than 520 miles of coastline. The city’s harbor is a national treasure and is cleaner now than it has been in more than 100 years, thanks to achievements in wastewater collection and treatment as well as a shift away from a heavily industrial economy. This rejuvenated waterfront provides economic, recreational, and environmental benefits to the city’s residents.

To continue to improve the quality of our waterways, increase opportunities for recreation, and restore coastal ecosystems, the 2011 version of PlaNYC sets forth a plan for the city’s waterways with 15 initiatives and more than 50 milestones.

Harbor Water

Over the past decade New York City has invested more than $10 billion to successfully improve water quality in the harbor. A $5 billion upgrade at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant will increase both the amount of pollution removed from the wastewater and the plant’s treatment capacity from 620 to 700 million gallons per day in wet weather. The plant went into operation in 1967, before Congress passed the landmark Clean Water Act, requiring municipalities to remove at least 85 percent of certain pollutants from wastewater before discharging it into surrounding waterways. An upgrade begun in 2000 brought the plant into compliance with Clean Water Act standards in 2011, two years ahead of schedule. Now all 14 wastewater treatment plants in New York City meet secondary treatment and removal requirements.

In addition, the city has made investments to upgrade and improve a number of other plants over the last ten years. At the Hunts Point Wastewater Treatment Plant, the city invested $595 million to increase wet weather capacity, build a new nitrogen removal system, and construct a central residuals facility to reduce odors from the plant. The city has also undertaken major upgrades to the 26th Ward, Coney Island, North River, and Owls Head wastewater treatment plants. Over the next ten years, the city will invest $3.3 billion to keep wastewater treatment facilities in a state of good repair.

Stormwater is a challenge for urban areas, such as New York City, that have combined sewers, which carry both sanitary waste and stormwater in the same pipe. When there is more rain than the system is designed to carry, the combined sewer is built to overflow into local waterways to mitigate damage to the wastewater treatment plants. Traditional solutions to many water

FIGURE 3 Paerdegat Basin Combined Sewer Overflow Detention Facility

quality challenges employ “grey infrastructure” (so called because it is often built with steel and concrete), such as the Paerdegat Basin Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Facility, that can detain wastewater until the treatment plants have the capacity to treat it (Figure 3). These facilities serve only one purpose and often are expensive to build; the Paerdegat Basin Facility, for example, cost approximately $404 million, but it is quite effective, eliminating 70 percent of CSO into Paerdegat Basin.

Artificial Wetlands (the Bluebelt System) and Green Infrastructure

First developed on Staten Island and now used in Queens and the Bronx, the bluebelt system provides ecologically sound, cost-effective stormwater management by preserving streams, ponds, and other wetland areas that collect stormwater runoff from the streets and temporarily detain or permanently retain it. In addition, the people that live nearby gain from the aesthetic and

environmental benefits of the wetlands and have seen their property values increase because of the amenities.

Bluebelts have proven to be effective at managing stormwater where the city has enough space for large artificial wetlands. However, in ultra-urban areas of the city, where approximately 72 percent of land is impervious (e.g., parking lots, roads, sidewalks), it is difficult to manage stormwater using the bluebelt model.

In 2008, the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability published the Sustainable Stormwater Management Plan, which concluded not only that green infrastructure was feasible in many areas of the city but that it could be more cost effective than certain large, grey infrastructure projects like the Paerdegat Basin CSO Facility. Two years later the city published the NYC Green Infrastructure Plan4 and subsequently entered into a revised consent order with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation based on the plan that will eliminate or defer $3.4 billion in traditional investments and achieve greater water quality improvements.

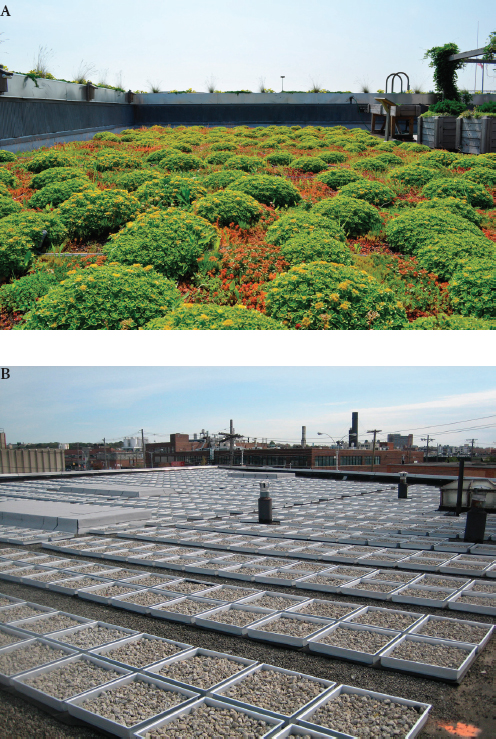

This approach provides the city with an adaptive and scalable toolkit of green infrastructure systems that can manage stormwater under, alongside, and on top of all varieties of urban structures. Green roofs and blue roofs are an ideal strategy for highly urbanized areas where buildings occupy a significant portion of urban land area (up to 45.5 percent in New York City). Porous pavement and pavers could be used in the city’s streets, sidewalks, and parking lots—which account for 26.6 percent of the city’s ground surfaces—if underlying soil and infrastructure can support the infiltration of water.5 And bioswales and stormwater greenstreets capture stormwater along the curb and prevent it from entering the sewer system. All of these systems provide additional benefits to the community such as higher property value, greater ecosystem diversity, and reduced urban heat island effect, among others.

Based on the performance of prototypes, DEP recently published standard designs for bioswales so that, just like traffic lights or fire hydrants, they are now part of the city’s palette of infrastructure. Each bioswale has a curb cut to divert runoff from the curb into the system. Next, a permeable gravel strip lets water seep into the water table, effectively removing this water from

___________________

4 New York City Department of Environmental Protection. 2010. Available at www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/stormwater/nyc_green_infrastructure_plan.shtml.

5Sustainable Stormwater Management Plan, New York City Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability, 2008.

the sewer system, increasing the system’s capacity, and reducing combined sewer overflows.

By 2015 DEP will have built or funded 6,000 bioswales and committed over $187 million to green infrastructure, creating a solid foundation for this program and adding to the distributed infrastructure that it will maintain.6

Stormwater Performance Standards and Other Initiatives

To address stormwater from new buildings, DEP published stormwater performance standards that require all new and redeveloped buildings to limit their stormwater outflow to approximately 10 percent of the current permitted flow into the combined sewer system. Some cost-effective methods to achieve this are detention (e.g., rain barrels and tanks), infiltration (e.g., permeable pavements and rain gardens), and reuse (e.g., grey water systems).

To address stormwater from existing buildings, the city has adopted a green roof tax credit, changed zoning rules to permit green roofs and other stormwater installations, and created a Green Infrastructure grant program that has funded 29 projects with $11 million in public funds that were matched by $5 million in private funds.

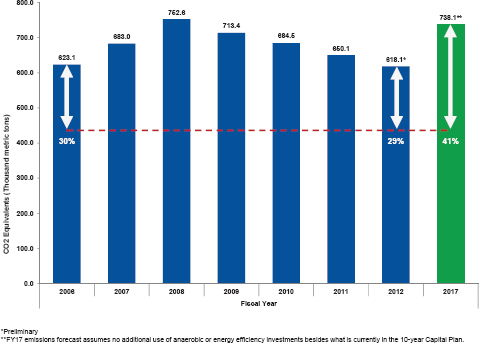

ENERGY

New York City’s energy and emissions goals include a more than 25 percent reduction in energy consumption by 2017 and a 30 percent reduction by 2030. To that end, DEP is helping to develop alternative and renewable energy supply projects (e.g., the city’s largest array of solar panels on the Port Richmond Wastewater Treatment Plant) and developing cogeneration at the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant. When complete in late 2017, the North River plant will be a prime example of highly efficient, clean distributed generation integrated in a dense urban environment. The plant will use its anaerobic digester gas to generate 15 megawatts of electricity while capturing and reusing waste heat, thus reducing greenhouse gas emissions by more than 40 percent from 2006 levels (Figure 5).

DEP is also working with National Grid to convert anaerobic digester gas from the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant to pipeline-ready natural gas. This project is the first example in the United States of injecting purified digester gas directly into a local natural gas distribution system.

___________________

6 DEP maintains 148,000 catch basins and 109,500 fire hydrants.

FIGURE 5 Current and Projected Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions, New York City. Dashed line = 30% reduction goal by 2017; white arrows with accompanying white text show the projected remaining GHG reduction. GHG emissions increase through 2017 because of new infrastructure including an ultraviolet disinfection facility and a water filtration plant. Source: New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

The gas, which normally would be flared, could heat up to 2,500 homes and would account for the removal of approximately 15,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases per year. After finalizing a contract with National Grid, DEP expects to begin construction in 2013 and put the system into operation by 2014.

AIR QUALITY

As the agency responsible for regulating air quality, DEP has launched a number of initiatives, such as a comprehensive revision to the New York City Air Code, which has been updated in a piecemeal fashion since its promulgation in 1975. The revision will streamline the code, increase ease of compliance, and regulate previously unregulated sources. The agency expects to present the updated code to the city council at the end of the year.

In April 2011 DEP established a new rule to phase out the use of No. 4 and No. 6 heating oils over the next 20 years. These regulations are expected to save more than 300 lives and avoid 600 emergency room visits and 200 hospitalizations each year by 2030. In July DEP and the New York City Department of Buildings streamlined the fuel change filing process, making the transition to cleaner No. 2 oil or natural gas faster and easier and saving building owners approximately $3,000 for each boiler conversion. In 2011 the city also announced the Clean Heat campaign, to assist property owners in complying with these regulations through education, outreach, and technical assistance.

CONCLUSION

The 2012 PlaNYC Progress Report showed that New York City has completed or made substantial progress on more than three-quarters of the milestones set forth in the 2011 version of PlaNYC. With responsibility for more than a quarter of the city’s initiatives, DEP is proud to be making significant contributions to protect the city’s public health and the environment by providing high-quality drinking water and collecting and treating wastewater. Over the past decade, DEP has invested more than $20 billion to protect our drinking water supply and improve the health of our waterways—more than any other city in the United States. And over the next decade, DEP will continue to invest more than $14 billion to further improve our infrastructure and continue to lead the nation in finding the most cost-effective, sustainable, and efficient ways to deliver high-quality drinking water and protect our waterways.