Appendix E

Women in IT: RECRUIT THEM & RETAIN THEM

Emily Blakemore, Angie Im, Channing Martin, Al-

bery, Melo, Sara Raju, and Liz Schuelke

The H. John Heinz III College, Carnegie Mellon

University

I. Introduction1

The lack of women represented in the Information Technology (IT) workforce is an economic issue that affects society at large. As women continue to experience barriers that discourage them from entering and staying in the IT industry, they are denied opportunities in a growing field that has, in recent years, seen gains in both earnings and employment. This study’s aim is twofold: first, to analyze the barriers that prevent women from joining the IT field and second, to provide small businesses with three actionable interventions they can implement to better recruit and retain women in IT positions.

For this study, the US. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ categorization of Computer and Information Technology positions will constitute our definition of the IT field and related occupations.2 They include the following occupational titles:

- Computer Hardware

- Computer Network Architect

- Computer Programmer

- Computer Scientist

- Computer Software Engineer or Developer

- Computer Support Specialist

- Computer Systems Analyst

- Database Administrator

- Information Security Analyst

- Network and Computer Systems Administrator

- Technical Support Specialist

- Web Developer

While the definition of small business varies across sources, for the purpose of this study small businesses are considered independently owned companies employing fewer than 500 employees.

II. Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to better understand and identify existing barriers that challenge the recruitment and retention of women in the IT field. The review was guided by four key questions (detailed in Table 1, below). Given the limited data available on women in IT positions within small businesses, the conclusions of this literature review were derived from studies conducted in larger corporations.

TABLE E-1 Guiding Questions for Literature Review

| For Recruitment | For Retention |

| 1. What strategies have been proven to be effective and are currently in place to attract women into the IT industry? | 1. What factors about a company enables a woman to continue working in the field and avoid leaving the industry? |

| 2. What are the current challenges in recruiting women for current computer science positions | 2. What are the challenges to keeping talented women in their current positions, or, the industry in general? |

For this review, variations of the following search terms and phrases were used: “retention of women in IT industry” or “recruitment strategies for women in IT industry”. These words were systematically entered into 10 research databases. Collectively, they resulted in over 300 articles for review, from which 25 of the most relevant were chosen as supporting documents to this study. Additional articles were identified ad hoc as required. The barriers that are analyzed

_________________

1 Businesses employ fewer than 500 employees represent 99.6 percent of all US companies and represent 43.4 percent of all reported payroll. Although IT occupations demonstrated strong potential for growth, women in IT occupations are declining—from 35 percent in 1994 to 25 percent in 2011. This study addresses issues and challenges faced by women in small and medium businesses in IT fields and related occupations

2US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2012. Computer and Information Technology Occupations. Available at www.bls.gov/ooh/computer-and-information-technology/.

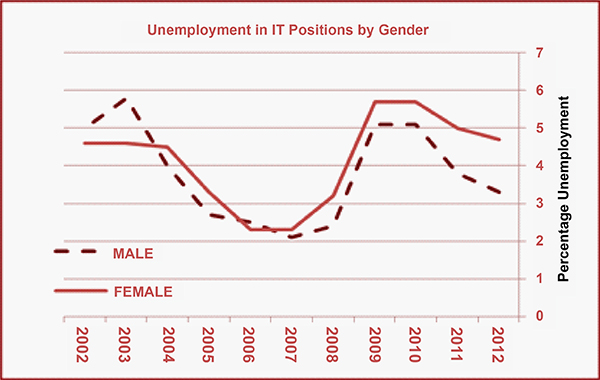

FIGURE E-1 Unemployment in IT Positions by Gender, 02-12. SOURCE: “Unemployed Persons by Occupation and Sex.” US Bureau of Labor Statistics - Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 5 Feb. 2013.

in the sections below were deemed to be the most relevant to small businesses.

A. IT and Small Business Overview

Steady economic gains in employment opportunities and earnings have been documented in the IT industry. IT occupations have consistently demonstrated strong potential for job growth.3 The US Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 17 percent employment increase across all IT occupations between 2010 and 2020, creating approximately 2.8 million jobs. Software Developers and Database Administrators, for instance, are expected to see the largest employment increases at 32.4 percent and 30.6 percent respectively.4

In January 2012, while the nation was experiencing 8.3 percent unemployment, IT occupations reported unemployment numbers as low as 3.8 percent.5,6 When unemployment increased to 8.8 percent nationally in January 2013, total unemployment in IT positions only marginally increased to 3.9 percent. However, in spite of these optimistic numbers, there is stratification across gender within the IT workforce. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2011 women in computing positions experienced 5.0 percent unemployment while men reported much lower rates at 3.8 percent. By 2012, the unemployment rate for women in IT dropped marginally to 4.7 percent, but the rate for men remained even lower at 3.3 percent. As is evident in Figure E-1, unemployment disparity between men and women in IT occupations has gotten worse in recent years.

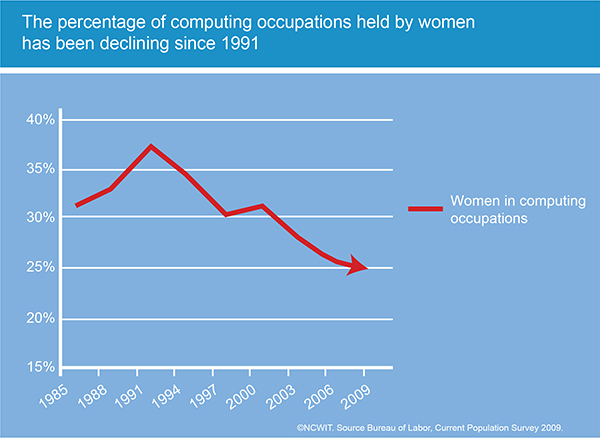

Despite the expected growth in IT occupations, the representation of women in IT positions continues to decline. From its peak in 1991, the percentage of women serving in IT positions has steadily decreased, reaching its current level of less than 20 percent (See Figure E-2).

The US Small Business Administration identifies small businesses in one of two ways: either by average annual receipts or average employment levels. Depending on the industry, the average small business can employ fewer than 500 people, but as many as 1,500. Similarly, annual receipts can range from less than $750,000 to $33 million.7 According to the United States Census Bureau, businesses that employ fewer than 500 employees represent 99.6 percent of all U.S. companies.8 For firms employing less than 500 workers, they represent 43.4 percent of all reported payroll and firms with less than 1,500 employees report controlling 52 percent of the total U.S. payroll. Given that small businesses represent a considerable part of the U.S. workforce, focusing on them is particularly compelling.

B. Barriers to Recruitment

Relevant literature suggests that gender bias in the workplace is a result of social inequalities that are perpetuated by institutional mechanisms.9 These institutional mechanisms include - but are not limited to - factors such location, work

_________________

3Luftman, J., and Kempaiah, R.M. 2007. “The IS organization of the future: The IT talent challenge.” Information Systems Management 24(2):129–138.

4“Career Outlook Information.” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Web. 14 Mar. 2013.

5“Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject.” Bureau of Labor Statistics Data, US Department of Labor, n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2013.

6“A-30. Unemployed Persons by Occupation and Sex.” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Web. 14 Mar. 2013.

7“Table of Small Business Size Standards Matched to North American Industry Classification System Codes.” US Small Business Association. 19 Mar. 2013

8“US – All Industries – by employment size of Enterprise.” Statistics of US Businesses. United State Census Bureau. Web. 19 Mar. 2013.

9Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, and Lawrence Bobo. 1994. “Social dominance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67(6):998–1011.

FIGURE E-2 Percentage of Computing occupations Held by Women (1985–2009). SOURCE: NCWIT. Bureau of Labor. Current Population Survey 2009.

place policies, the physical environment, culture and other ancillary elements such as benefits or services that characterize an employee’s work experience. These institutional mechanisms, which promote gender bias, exist across many industries; however the IT industry is especially susceptible to this gender bias, as it is largely male-dominated.

Job Posting Bias

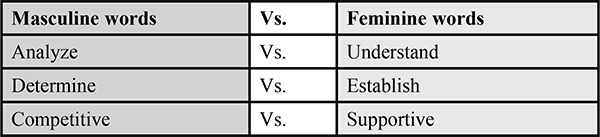

Literature reveals that there is subtle gender bias in IT job postings, deterring women from seeking technical positions. Specific words used in job postings can be associated with a single gender, and can have the effect of appealing to one gender over another depending on the cue words used. Most women prefer jobs targeted for their own gender to jobs targeted for men.10 Cue words have the effect of appealing not just to a particular gender but also to the belief systems that ultimately construct the gender stereotypes. In general, women respond better to language that communicates more communal and interpersonal qualifications, in contrast with men who prefer language associated with leadership and agency.11

FIGURE E-3 Examples of Masculine Words Versus Feminine Words

Literature indicates that the wording in male-dominated jobs (such as engineering, computer science, and mechanics positions) is often characterized as more masculine language than feminine.12 Language is one of many situational cues which individuals rely on in determining fit. Studies show that situational cues affect a women’s sense of belonging especially in math and science fields. Women prioritize a sense of belongingness as important in employment.13 Current literature indicates that cue words in job postings that motivate women convey a greater sense of belonging than the masculine words used.14 Ultimately, if women do not view the industry as welcoming, they will be less likely to even apply to for IT jobs. This subtle bias in the job posting language is deterring women from even applying for jobs in male-dominated fields, including the IT industry. This language bias is an example of an institutional mechanism, which is perpetuating the gender gap in IT.

The Physical Environment

The physical environment is an important element in attracting women to IT positions. Physical environment includes the external environment as well as the structural and material components of a physical workspace. Both the geographic location of a company, as well as the actual office space, can be factors affecting the recruitment of women in the industry.

Relevant literature indicates that workspaces, which take into consideration the cultural priorities of their employees, are the most successful at increasing productivity and enabling employees to achieve their full potential.

_________________

10 Gaucher, Danielle, Justin Friesen, and Aaron C. Kay. 2011. “Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101(1):109–128.

11Stahlberg, Dagmar, Friederike Braun, Lisa Irmen, and Sabine Sczesny. 2007. “Representation of the Sexes in Language,” pp. 163–181. In: Social communication, ed. Klaus Fiedler. New York: Psychology Press.

12Gaucher et al. (2011), op.cit.

13Ibid.

14Bem, S.L., and Bem, D.J. 1973. “Does sex-biased job advertising ‘aid and abet’ sex discrimination?” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 3(1):6–18.

As employees attach sentiments and a sense of identity to their workplace, they prioritize the physical space.15 Both males and females have a desire to fit into their work environment. Fit is measured by both the sense of belonging employees feel to their environment as well as how similar they feel to other individuals in that environment.16 Physical environment includes objects such as the lighting, posters, the décor of common spaces and decorative objectives such as books, magazines, etc. and any other component of the environment, which dictates a particular culture or feeling. Current literature has shown that the layout of physical workspace not only improves an employee’s feelings about their work environment but can also positively affect work performance.17

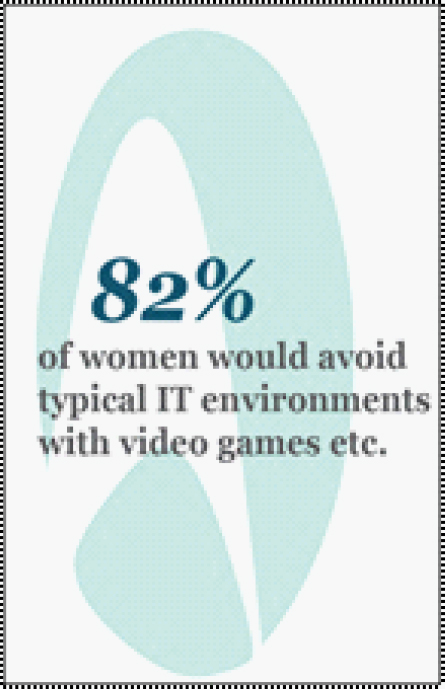

Research reveals that stereotypical environments marginally reduced women’s identification with the computer science field. However, the environment had little effect on men’s identification. Women also avoid environments populated with stereotypical objects associated with computer science such as Star Trek posters and video games.18

These elements inform the culture of a particular space, which women often associate with feelings of fit. Male-dominated fields, such as computer science, typically have work environments that reflect this male. This can include items ranging from gaming posters to certain magazines, and even something as innocuous as soda cans. Women who perceive that they will not be in an inclusive workspace are likely to be deterred from entering into it. As workspaces become increasingly more open, employees strive to personalize their workspace.19

It is clear that environments can play a role in shaping gender stereotypes. However, research indicates that the way employees view their physical workspace has shifted from previous sentiments. Today, employees look beyond functional comfort in their physical environments to improve their productivity.20 Reducing stereotypes in an environment is no longer dependent on there being a gender balance.

The external environment can also play a crucial role in shaping a woman’s sense of belonging. As the IT industry continues to grow, cities where the industry is dominant are beginning to see cultural and economic shifts that subtly change the very character of those cities.21 This character shift contributes to the desirability of an IT position being made available in one geographic area over another, and can be another factor influencing recruitment of women in IT. Another factor important to women is the cultural environment as it relates to livability.22 This includes the cultural mindset of a city, the personal and professional networks available, perceived livability of a city, cultural diversity as well as the communities and schools. Economic factors important to women include cost of living and dominant industry in a particular location. These factors can influence the social acceptability of women participating in the workforce. For instance, if the dominant industry is male-dominated or if the cost of living is so high that it requires a second income; there is a recognized need for a two-income household. This might mean that women will participate more in the work force.23 In cities with a more diverse industry base, the social acceptability of women working is higher.

Both the internal and external environment plays a role in determining a woman’s sense of belonging in their workplace. Employees prioritize the need to fit into their work environment - both the physical office space as well as the geographic location of their office. Removing stereotype from the internal physical environment can lead to a greater sense of belonging and better fit for an individual.

C. Barriers to Retention

While recruiting efforts are crucial for increasing the representation of women in IT positions, it is equally important that women, once recruited, are retained.24 Recognizing employees’ needs and individual desires is essential for understanding what influences their occupational selection or intention to leave an organization.25 Workplace culture and the theory of gendered roles are critical factors to examine for the retention of women in any industry but especially

_________________

15 Meerwarth, Tracy L., Robert T. Trotter II, and Elizabeth K. Briody. “The Knowledge Organization: Cultural Priorities and Workspace Design.” Space and culture 11(4):437-454.

16Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. 2009. Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97(6):1045–1060.

17Vischer, Jacqueline C. 2008. “Towards an Environmental Psychology of Workspace: How People Are Affected by Environments for Work.” Research Group on Environments for Work, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Montreal.

18Cheryan et al. (2009), op. cit.

19Vischer (2008), op. cit.

20Ibid.

21Trauth, Eileen M., Jeria L. Quesenberry, and Benjamin Yeo. 2005. The influence of environmental context on women in the IT workforce. Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGMIS CPR conference on computer Personnel research. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

22Ibid.

23Ibid.

24Tapia, Andrea H., and Lynette Kvasny. 2004. “Recruitment Is Never Enough: Retention of Women and Minorities in the IT Workplace.” ACM SIGMIS Database 10. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=982392

25Chang, C.L., Chen, V., Klein, G., and Jiang, J.J. 2011. “Information system personnel career anchor changes leading to career changes.” european Journal of Information Systems 20(1):103–117.

key to combat attrition in IT occupations.26 Their departure, in turn, can lead to both high economic and social costs, as companies lose organizational experts and expend resources trying to secure a replacement.27

Workplace Organizational Factors

Academic literature on the IT workforce consistently reports that women excel in environments that promote cooperation and hands-on learning.28 However, this organizational culture is often not indicative of the IT field, and the lack of such a culture can cause women who enter the industry to feel isolated within their work environments. Without internal support networks, such as a mentor who might help mitigate these feelings, women may become dissatisfied with their jobs and subsequently exit the IT workforce.29 However, ongoing professional development facilitated through mentorship programs and female role models can be highly effective in mitigating the daily pressures encountered in the IT field (such as the constant need to acquire new skills, adjust to new roles, and manage competing priorities), ultimately enhancing work satisfaction and increasing the overall retention of women in the field.30,31

Women, who are in an IT environment that actively promotes such collaborative initiatives, have been shown to benefit greatly. As they build close relationships and establish support networks within the organization, they learn how to successfully navigate challenges and barriers they are likely to encounter in the field. These internal connections can also play a critical role in their advancement within the IT industry.32

Organizational use of role models can also be effective in retaining women in IT positions. Linking female employees with other IT professionals, especially another female, can help mitigate the risk of role ambiguity common to the IT field. Factors, such as extended work schedules without consideration for outside commitments, an emphasis on individual innovation over teamwork and valuation of an employee based on technological rather than soft skills, are all industry characteristics which lead to uncertainty among women about job responsibilities or work expectations.33 Role models can serve as socializers within the organization, helping women acclimate to the culture and workplace environment.34 The benefits accrued when women form bonds, even informally, with other women in their workplace positively impacts the retention of women in IT occupations. These connections provide a platform for women to share best practices and learn the tools they need to succeed in their jobs.35

Gendered Roles

Some of the relevant literature suggests that the way children are socialized may carry over into the workplace. The concept of gendered roles, where from an early age girls are taught to be caregivers, while boys are encouraged to be competitive, is often thought to be an influencing factor. This theory might explain why women gravitate towards communal careers and eventually exit the IT workforce.36 While men are more likely to pursue careers that grant them agency, usually in the form of status and financial gain, women instead seek positions that enable them to make a contribution and tend to prioritize helping society.37 Consequently, women can perceive IT-related careers as being incompatible with their communal goals, whereas men are drawn to the high earnings and relative prestige that the field provides.38

These gendered schemas lead to the perception that women are only good at certain tasks and ultimately lead to an undervaluation of their skills by society. For instance, although identified as important to the IT industry, skills such as relationship building and communication are valued less because they come “naturally” to women and are not considered an achievement. Moreover, since women are often considered to be more detail-oriented than technical, they are pushed into administrative, documentation-oriented and training roles. The perception of women as less technologically capable than men will only continue to contribute to the underrepresentation of women in the field.39

Already an occupation characterized by the need for

_________________

26 Wentling, R.M., and Thomas, S. 2009. “Workplace culture that hinders and assists the career development of women in information technology.” Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 25(1):25–42.

27Riemenschneider, Cynthia K., Deborah J. Armstrong, Myria W. Allen, and Margaret F. Reid. 2006. “Barriers Facing Women in the IT Work Force.” ACM SIGMIS Database 37.4:58. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1185345

28Tapia and Kvasny (2004), op. cit.

29Trauth, E.M., Quesenberry, J.L. and Huang, H. 2009. “Retaining women in the US IT workforce: Theorizing the influence of organizational factors.” European Journal of Information Systems 18(5):476–497.

30Simard, Caroline, and Shann K. Gilmartin. 2010. “Senior Technical Women: Profiles of Success.” Palo Alto: Anita Borg Institute for Women and Technology. Available at http://anitaborginstitute.org/news/archive/senior-technical-women-profiles-of-success/.

31Tapia and Kvasny (2004), op. cit.

32Wentling and Thomas (2009), op. cit.

33Riemenschneider, Cynthia K., Deborah J. Armstrong, Myria W. Allen, and Margaret F. Reid. 2006. “Barriers Facing Women in the IT Work Force.: The Database for Advances in Information Systems 37.4.

34 Drury, Benjamin J., John Oliver Siy, and Sapna Cheryan. 2011. “When do female role models benefit women? The importance of differentiating recruitment from retention in STEM. Psychological Inquiry: an International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory 22(4):265–269.

35Roldan, Malu, Louise Soe, and Elaine K. Yakura. 2004. “Perceptions of chilly IT organizational contexts and their effect on the retention and promotion of women in IT.” ACM SIGMIS Database, available at http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=982399..

36Riemenschneider et al. (2006), op.cit.

37Cheryan, S. 2012. “Understanding the paradox in math-related fields: Why do some gender gaps remain while others do not?” Sex Roles 66(3-4):184–190.

38 Harris, N., Cushman, P., Kruck, S.E., & Anderson, R.D. 2009. “Technology majors: Why are women absent?” Journal of Computer Information Systems 50(2):23–30.

39Roldan et al. (2004), op. cit.

continuous education; as one known for its extreme and unusual time demands and filled with professionals stereotyped as geeks; the organizational climate found in many IT occupations does little to reduce attrition rates of women.40 If a woman’s perception of an organizational environment is hostile, male-dominated or unwelcoming, it can negatively influence her decision to remain in an IT position. Unfortunately, most studies have focused on assimilating women into the dominant organizational environment instead of addressing the need for these organizations to modify existing values and change negative perceptions. If companies hope to effectively recruit and retain women in IT professions, they need critically reevaluate current occupational climates.41

D. Summary

The comprehensive review of relevant literature revealed a couple key barriers preventing women from wanting to work in IT positions. While several main factors emerged as important, this study’s aim is to analyze those barriers most relevant to small businesses. Therefore, the literature review strove to provide an understanding of the small business landscape and an analysis of the IT industry, and then aimed to use these factors to analyze the main barriers preventing women from joining IT roles in small businesses.

The combination of the large number of small businesses in the U.S., a projected growth in the IT industry, and the low percentage of women in IT makes small businesses an excellent platform from which to improve the recruitment and retention of women in IT occupations.

In identifying barriers to recruitment the main factors that emerged were largely institutional biases, including biases in job posting language and the physical work environment. Relevant literature reveals that there is a bias present in current job posting language which has the effect of deterring women from applying to IT occupations. As online job postings are the most prevalent place to find jobs, and the Internet the greatest search tool, it seems that the removal of this barrier could serve as an achievable target for small businesses. Often, small businesses do not have recruitment resources like recruitment fairs or professional services and therefore rely more heavily on Internet postings to recruit candidates.

The physical environment was also identified as a barrier to both recruitment and retention for women in IT occupations, with the internal physical environment representing a priority to employees. Employees - both male and female - associate the physical environment with their feeling of fit into an organization or culture. Environments help create a sense of belonging among employees, and currently most IT environments are largely male dominated which detracts from a woman’s sense of belonging in the space. Thus, the design, décor and layout of the physical work environment is important in making women feel connected to their work culture and the people they work with.42 Small businesses are at a unique advantage to combat this barrier as usually they have smaller offices, fewer employees and flexible policies, which would allow them to more easily dictate how the physical space is used and use it to avoid this as a barrier to women.

The main barriers to retention that were identified as being particularly important to small businesses are organizational factors in the workplace and gendered roles. Collaborative work environments motivate women and they prioritize them in evaluating their job satisfaction.43 Mentorship, professional development programs, and internal networks are all factors that contribute to a collaborative work environment.44 A presence of these initiatives has been shown to improve a woman’s work experience as it provides strong internal networks and builds personal relationships, both of which increase a woman’s job satisfaction and help them advance in the field.45

Furthermore, the idea of gendered roles is a barrier to recruiting women in IT positions. Males and females are socialized with the idea that each gender has a designated role that each is better suited for.46 By and large, women are considered to be more suitable for work that is communally oriented and that contributes to society. However, the nature of the IT industry and expected duties conflict with that notion, consequently deterring women from wanting to stay in the field.47

The removal of these barriers are important and achievable by small businesses as they are more readily able to make changes in the work environment, and have more flexibility implementing initiatives when compared to larger companies. The latter may be constrained by stringent policies and often have a more complex process to implement change.

_________________

40Ghazzawi, I. 2008. “Job satisfaction among information technology professionals in the U.S.: An empirical study.” Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge 13(1):1–15.

41Trauth, E.M., Quesenberry, J.L. & Huang, H. 2009. “Retaining women in the U.S. IT workforce: Theorizing the influence of organizational factors.” European Journal of Information Systems 18(5):476–497.

42Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. 2009. “Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97(6):1045–1060.

43 Wentling, R.M., and Thomas, S. 2009. “Workplace culture that hinders and assists the career development of women in information technology.” Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 25(1):25–42.

44Senior Technical Women

45 Wentling, R.M., and Thomas, S. 2009. “Workplace culture that hinders and assists the career development of women in information technology.” Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 25(1):25–42.

46Riemenschneider, Cynthia K., Deborah J. Armstrong, Myria W. Allen, and Margaret F. Reid. 2006. “Barriers facing women in the IT work force.” ACM SIGMIS Database 37(4):58.

47Cheryan, S. 2012. “Understanding the paradox in math-related fields: Why do some gender gaps remain while others do not?” Sex Roles 66(3-4):184–190.

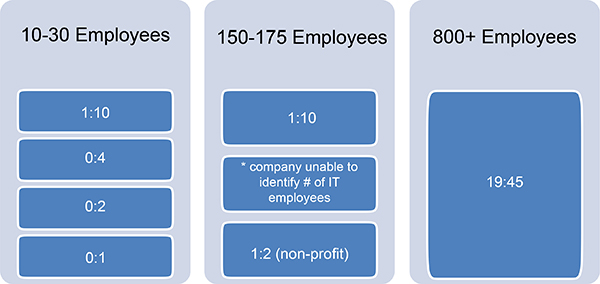

FIGURE E-4 Ratio of Female to Male IT Employees in Each Participating Company (Grouped by Company Size)

III. Methodology

Data gaps revealed in the literature review were explored through the development of case studies of eight companies. Case study information from each company was gathered from both the employer perspectives and employee perspectives. To obtain the employer perspective, an interview with one hiring manager, human resource professional, and/or IT supervisor within the organization was conducted. To obtain employee perspectives, an electronic survey was administered to employees that the company identified as filled IT positions.

Company Selection

Initially, 49 companies were contacted by phone, email, or through the use of LinkedIn postings that were placed advertising an opportunity to participate in the study. Ultimately, eight of the 49 companies (16 percent) were recruited to participate in both the interviews and surveys. Those eight companies represented a combination of privately and independently-owned small businesses, as well as one non-profit organization, and one medium-sized business (the latter two companies were included for comparative purposes).48 Only companies employing full-time IT employees were included in this study. Companies that used only contracted IT sources were not included, and contract IT employees within the selected companies were also not included as part of the case studies. (See Appendix E-5. Participant Company Descriptions for company descriptions.)

Employer Interviews

The employer interview questions were designed to gather specific information about recruitment and retention efforts from the employer perspective. The questions required the interviewee to discuss the company’s hiring practices, organizational culture, and investment in their employees. The interviews were intended to determine the strategies used by companies to address barriers to recruitment and retention of women in IT positions, and what they have done to create more inclusive environments in their workplace, especially among IT professionals. (See Appendix E-4. Interview Questions.)

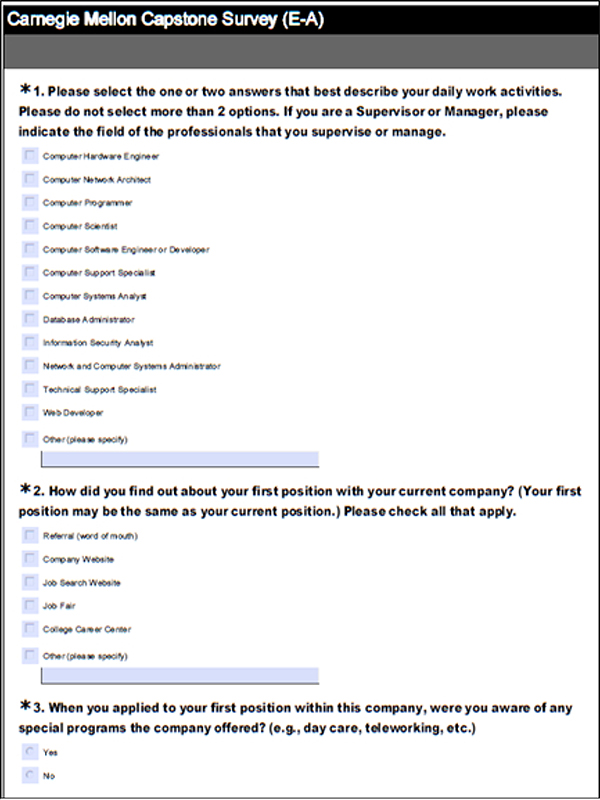

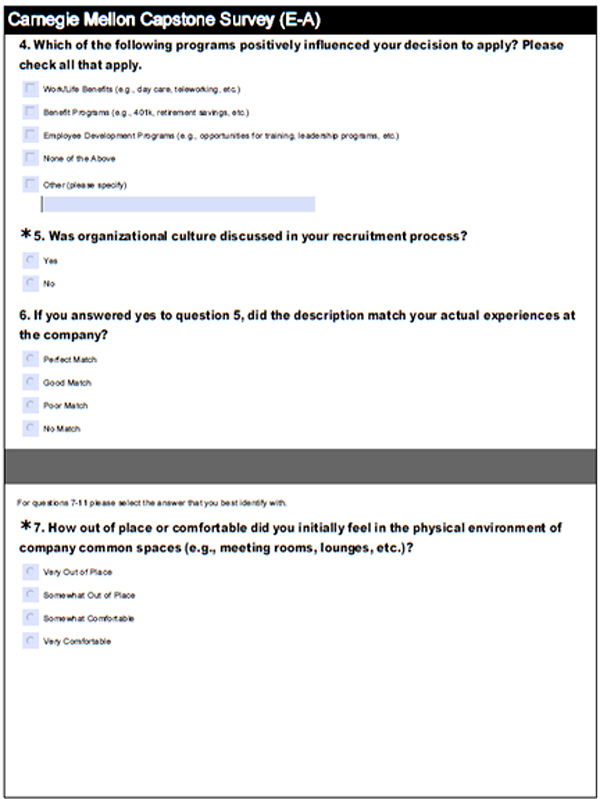

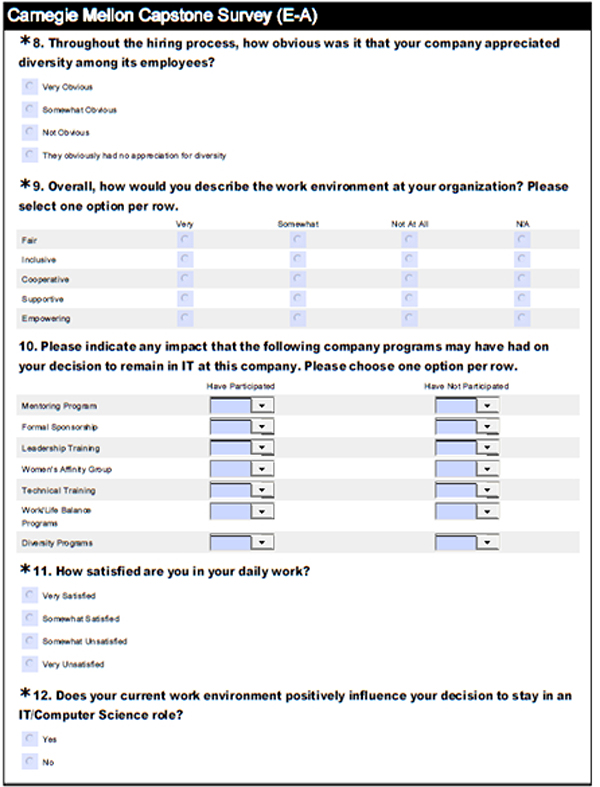

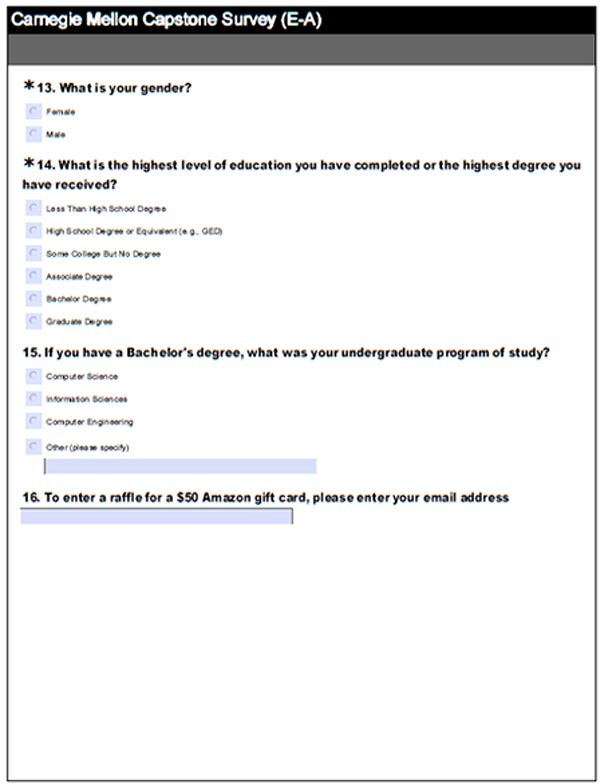

Employee Surveys

To gather employee perspectives, the general hiring manager (or IT manager) who was interviewed was asked to distribute an online survey link to employees whom they identified as filling IT positions. Surveys were administered and collected within four to seven days. The survey was developed to gather insight into an employee’s perception of belonging, investment within the company, and experience in IT roles within a small business. The survey included rating scale, multiple choice, and “yes” or “no” questions. Participants were incentivized to respond to the survey with the opportunity to win a $50.00 Amazon gift card. (See Appendix E-3. Online Survey.)

IV. Case Study Findings

A. Interview Results

The following section provides an overview of the responses from eight case study interviews.

Demographics– Gender Landscape

The first interview question sought to identify gender representation among the total employees within each company, as well as among just IT employees. Of the four companies employing 10-30 employees total, one company had 1 female IT employee (of 11 IT employees), and the other three companies employed no female employees (of 2, 4, and 1 IT employees employed within those three firms). Of the three companies employing approximately between 150-175 employees total, one company reported employing 1 female IT employee (of 11 IT employees); the interviewee for the second company was unable to enumerate their number of IT employees; the third company was a non-profit organization employing three IT employees, one of whom

_________________

48The Small Business Administration (SBA) defines a small business concern as “one that is independently owned and operated, is organized for profit, and is not dominant in its field. Depending on the industry, size standard eligibility is based on the average number of employees for the preceding twelve months or on sales volume averaged over a three-year period.”

was female. Figure E-4, represents each of the eight companies in our case study and their ratio of female to male IT employees. All companies are grouped by company size.

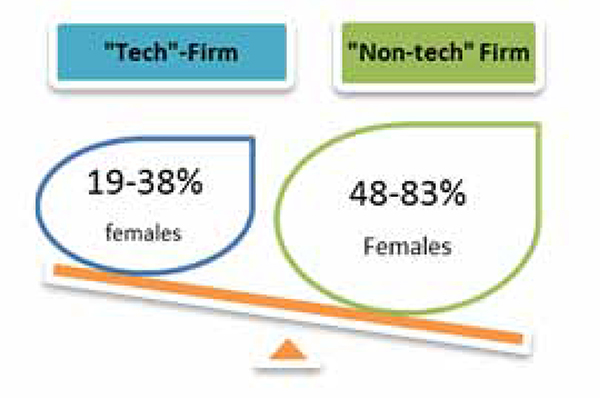

The four companies who could be described as “tech-oriented”49 (their major services include web development, hosting services, data collection, e-commerce, data delivery, etc.) employed not only fewer women in IT positions than men, but also fewer female employees across all positions [19 percent-38 percent] (the non-tech-oriented firms had greater representation of women across their total number of employees [48 percent - 83 percent]). (Figure E-5)

Attracting Applicants Through Job Postings

Each company described their recruitment process and the specific strategies that they employ to attract talent. The four companies with 10-30 employees all described processes where they post open positions on trusted job sites. One of these small companies uses a third-party recruiter, similar to that of a headhunter to find appropriate talent. The most common recruiting efforts were posts on job sites, job boards, and promoting through colleges and universities. Craigslist in particular has been utilized as well as access to talent through relationships with universities. Once received, resumes are then filtered through by subject matter experts based on resume and experience. The remaining larger companies employing around 150-175 employees indicated similar hiring efforts as those of smaller organizations.

Job Posting Response

We also asked about the most recent technical position for which the company sought applicants, along with the number of people that applied, estimated number of female applicants, and final outcome of the search. Although companies could not definitively provide the number of female applicants,50 three of the companies with 10-50 employees reported interviewing at least 1 female applicant.51 One of those companies made an offer to a female candidate (final outcome pending), one company hired a man, and one company did not hire anyone, citing a lack of qualified candidates of either gender. When asked this set of questions, three of the companies cited the following reasons for not hiring women: Not qualified, didn’t have background/training relevant to the open position, lack of women in the field (specifically for “developer-oriented” positions), lack of “technical” skills.

“… the skills we saw on resumes were not technical enough. They were mostly database admins or co CPAs.”62

- Interviewee IT Manager

FIGURE E-5 Total female representation within participating companies – Comparing “Tech” vs. “Non-Tech” firms*

For the larger companies: two of the three companies with approximately 150-175 employees demonstrated greater numbers of female applicants, citing that 22 [50 percent] and 14 [23 percent] women applied of 44 and 62 applicants, respectively. The latter company stated that they ultimately hired a male because “the skills we saw on resumes were not technical enough. They were mostly database admins or co-CPAs52.” The third company (the non-profit) reported having 2 or 3 female applicants of 12-13 total resumes [20 percent]. The company with >500 employees could not state the number of female applicants among males, but they estimated that about 50 percent of resumes received were from females.

Determining Fit Through the Hiring Process

As a part of the hiring process all of the employers mentioned the need for candidates to feel that these companies were a good fit. One of the smallest companies in the study requires new-hires to undergo a 30-day trial period before they join full-time. They essentially work as contractors for 30 days to prove their skills match what they have claimed, and allow an opportunity for the company to see if they are a good fit. Another employer said, “After the in-person interview at that point we’re trying to get a feel for a culture fit.”

Targeted Recruitment and Retention Initiatives for Women

The results of the interviews also provided information on each company’s recruitment and retention activities for women specifically. The companies with 10-30 employees indicated that they do not participate in efforts specifically targeting women. One of these companies commented, “A lot of the – what we’ll call, company diversity initiatives – they’re not explicit.” Results of the employer interviews revealed the majority of retention efforts do not include specific efforts to retain women like maternity leave or other female-targeted initiatives (Figure E-6).

“A lot of the – what we’ll call, company diversity initiatives – they’re not explicit.”

- Interviewee IT Manager

_________________

49See Appendix E-5. Participant Company Descriptions for more information on companies defined as tech vs. non-tech.

50Because they could not identify gender through resumes submitted.

51Employer G did not participate in this question because the interviewee did not have data for this question.

52Co-CPAs refer to certified public accountants who are also database administrators.

FIGURE E-6 Elements that add or subtract from retention efforts.

All eight companies mentioned similar benefits such as retirement plans, informal mentoring programs, and paying for IT skill improvement classes. When asked about benefits programs, not one company mentioned maternity leave. One of the businesses with less than 50 employees explicitly stated they do not offer maternity leave, adding that no one has requested such a leave. When asked what would happen if a potential new female hire were to ask about maternity leave, they responded, “I’m pretty sure that would be one of their questions, and that would obviously be one consideration. The decision would ultimately be up to the lead hirer, though. I would see it as a hiring negotiation.”

The larger companies with about 150-175 employees do not have special campaigns or initiatives that target women during their recruitment efforts. One larger company said, “I just want to hire the best candidate to be totally honest.” Alternate work schedules were popular benefits provided by the larger companies, but there were no formal mentoring programs available.

Elements of Organizational Culture

Lastly, the employer interview aimed to measure what elements made up the culture of their organizations. Companies with 10-30 employees typically describe their organizations to be creative and open environments that are flexible to employees’ needs. They described their cultures as, laid back and casual even outside the workplace. All the companies in our study with 10-30 employees have two or fewer women working in their IT departments. Companies with about 150-175 employees describe their workplaces to be results-oriented, but also casual. Dress code is rarely emphasized, and hard work is often rewarded with social events. The theme of work hard, play hard was typical throughout the interviews.

Workplace factors - Workload/Time commitment

To better understand the expected hourly commitment for IT employees, we asked employers about their practices related to employees being on-call outside of regular business hours. Four of eight companies in the study were asked whether they require IT employees to be on call.53 Of those four companies, only one company required all IT employees to rotate on-call duties (one of the four tech-oriented firms). Two companies reported only managerial positions (only men were in managerial roles in these companies) to occasionally be on call or to have to work non-scheduled evening hours. One company did not require on-call duties from any employees.

Interview results for Medium Sized Companies

We interviewed one company with just under 900 employees, that we are calling medium sized to compare to the small sized companies included in the study. The firm is female dominated, but the IT department is less than 50 percent female. The company is large enough offer full benefits for healthcare, but they do not offer telework. The culture is very demanding and corporate and IT professionals are expected to be readily available to perform their duties with high quality and very timely. They did not provide or target women specifically in their recruiting or retention efforts.

Interview Results for Non-profits

Additionally for comparison, we included a small nonprofit in the study with 170 employees. This is an academic organization that ties benefits to incentives by offering discounts to their employees on the services they provide. For example, employees who have been employed more than 1 year receive a discount on tuition for their child. The organization is largely female due to the benefits offered. There are no formalized programs for alternative work schedules, mentoring or training; but they are offered and received on an as needed basis. The mentoring program that is available is geared toward faculty and not the staff. The non-profit does not have any formal recruitment programs and does not target women specifically, even though they do think it would be beneficial to have a structured program because qualified technical professionals have been hard to find.

B. Survey Results

Demographics of Survey Respondents

The companies that participated in our study varied widely in size and in IT capacity. Naturally, the bigger companies employed more IT personnel in comparison to the smaller ones. This variation is reflected in the number of respondents (See Table E-2, below). Of the 45 employees surveyed, 39 submitted complete responses. These results were then analyzed and formed the basis for our analysis. Males outnumbered females in the survey sample, with about 79 percent of the respondents identified as male and 21

_________________

53The other four were not asked this question because the interviewees participating in this study were general hiring managers or human resource professionals who could not provide this information.

TABLE E-2 Participating Companies: Size and Employee Respondents

| Company | Company Size | IT Department Size | # of Employee Respondents | |

| A | 10-30 | 6 | 4 | |

| B | 10-30 | 4 | 2 | |

| C | 10-30 | 11 | 7 | |

| D | 500-1000 | 64 | 19 | |

| E | 150-175 | 11 | 2 | |

| F | 150-175 | 3 | 2 | |

| G | 11-50 | 1 | 1 | |

| H | 100-500 | --* | 2 | |

* Employer was unable to identify the number of IT employees.

percent as female. Small business employees represented 46 percent (18 respondents) of total respondents, while 49 percent (19 respondents) were employed at the medium-sized company and 5 percent (2 respondents) were employed by a nonprofit.

Job Posting

With respect to staffing and recruitment methods, the majority of the small business respondents reported finding their jobs with current employers through job search websites (including Craigslist) and a few reported finding their position through a referral. For every three employees in a small business, at least one reported to have found their current position through an online job post than through a referral. In contrast, the medium-sized business respondents were divided between referrals (38 percent of respondents) and job search sites (33 percent). Analysis by gender revealed that women were more likely to have found their jobs via referral, with 62.5 percent of all female respondents indicating that they found their position this way and 13 percent who reported finding their position through a job posting.

Physical Environment

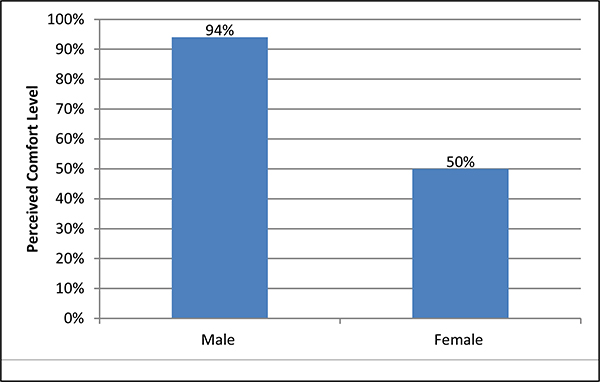

When respondents were asked about comfort levels within their physical environment, they were more likely to respond positively concerning their workspace. Of the 39 respondents, 33 reported feeling “Somewhat Comfortable” or “Very Comfortable.” Small business employees were 20 percent more likely to be “Very Comfortable” than employees at the medium-sized business. Breakdown by gender indicates that the males in the survey were typically “Somewhat Comfortable” in their physical space. Of the male respondents, 90 percent reported feeling “Somewhat Comfortable” to “Very Comfortable” in their physical work environment. The women are more evenly divided, with 5 of the 8 respondents feeling “Somewhat Comfortable” to “Very Comfortable” with the remaining 3 feeling “Somewhat Out of Place” and “Very Out of Place”. These results indicate that women are often less comfortable in the IT workspace than their male counterparts, but that small business environments tend to be more welcoming overall. Small businesses can create a greater sense of ambient belonging among women by examining what aspects of the physical environment cause sentiments of discomfort. Ambient belonging is a concept that explains the connection between physical environment and fitting in.54

Competing Priorities

FIGURE E-7 Small Business Respondents Who Felt at Least Somewhat Comfortable in the Physical Environment.

_________________

54Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. “Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97.6 (2009): 1045-060. Print.

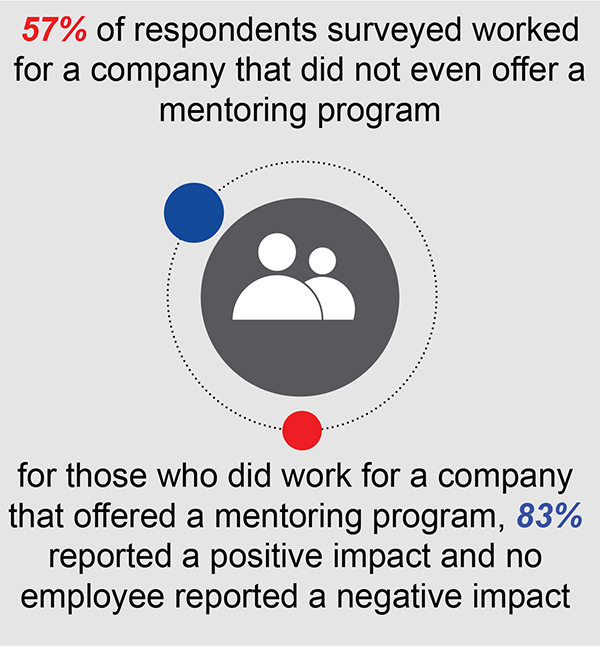

FIGURE E-8 Survey responses on mentorship

Company-sponsored programs, which enabled employees to balance work and personal priorities, were also a focus of the surveys. The questions were meant to assess the impact such programs had on employee retention rates. Survey responses indicate that all of the companies provided at least one type of work-life balance initiative (telework or alternative schedules), while employees at the non-profit reported that such initiatives were not offered. However, responses varied within companies, where some employees from one company reported participating in a program, and others within the same company indicated that no programs or initiatives were offered. Of the 39 respondents, just under half (17) reported participating in a company program aimed at helping employees manage competing priorities, and 14 reported that such a program positively impacted their decision to stay within the company. The remaining 3 respondents reported that they felt no impact from participating and none of the participating respondents reported a negative impact (Figure E-8).

When examining female responses, of the eight women surveyed, only two indicated they participated in company programs aimed at enabling employees to manage competing priorities. There were four respondents that did not participate in such programs, three of them worked for one company (identified as Company H), and the fourth female respondent worked at the nonprofit where such initiatives were not offered. The remaining two female respondents declined to answer.

The level of male participation in work life balance initiatives was high compared to the level of female participation. Across all companies, participation of women was only 25 percent, compared with the 50 percent participation rate among male respondents.

Since preliminary results indicate that participation in such programs positively impacts the respondent’s decision to stay with the company, but that few employees were actually aware of or participated in them, it follows that increased information and encouragement to participate could positively impact overall employee retention rates.

Gendered Roles

In an attempt to examine how closely the research findings discussed above, which state that women gravitate toward fields that foster a sense of belonging, match the sentiments of IT employees respondents were asked if they felt their work environment was “Fair”, “Inclusive,” “Cooperative,” “Supportive” and “Empowering”.55 These responses were then scaled from “Very” to “Somewhat” to “Not at All.” Most employees rated all categories between “Very” and “Somewhat,” with only a few respondents answering “Not at All.” However, comparison across genders demonstrated that women were more likely to reply “Somewhat” in all categories than their male counterparts.

In the inclusiveness category men were evenly divided, with 14 reporting their workplaces were very inclusive and 16 indicating that they were only somewhat inclusive. While only one male employee responded that the environment was not inclusive at all. Only 12.5 percent of women reported that their work environment was very inclusive, while 75 percent felt only it was somewhat inclusive, and the remaining 12.5 percent felt it was not at all inclusive. Comparison across companies demonstrated that employees at small businesses were 21 percent more likely to feel their work environment was inclusive than at nonprofit or medium size business.

When analyzing response within the “Supportive” category, the majority of women reported feeling their workplace was somewhat supportive, while the majority of men reported feeling their workplace was very supportive. The majority of male respondents also reported their workplaces to be Very Fair, Very Supportive, Very Cooperative, and Very Empowering, while the majority of women reported their workplaces to be Somewhat Fair, Somewhat Cooperative, Somewhat Supportive, Somewhat Inclusive and Somewhat Empowering. These results do little to refute women’s current perception of the IT workplace being unwelcoming and an environment where they would not feel the same sense of belonging that their male colleagues reported.

When respondents were asked if their current work environment encouraged them to stay in an IT occupation, 85 percent of all respondents said “Yes.” Among women, 62.5 percent replied that their current work environment encouraged them to stay in an IT position, whereas 87 percent of men expressed the same sentiment. Examining the data by the size of company also revealed similar breakdowns, with 83 percent of small company employees responding “Yes” and 86 percent from the medium company and nonprofit.

C. Summary

Upon analyzing the case studies several themes of interest emerged between employer and employee responses. One such theme within the recruitment process was that of

_________________

55 Gaucher, Danielle, Justin Friesen, and Aaron C. Kay. “Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality.” Journal of personality and social psychology 101.1 (2011)

job postings. Survey analysis revealed that the majority of respondents from small companies and the comparison firms (i.e., the medium-sized company and non-profit) found their positions through referrals, word of mouth or job postings on the internet. As the research has shown, job postings for IT jobs can be problematic in that they tend to favor syntax that describes typically male traits, and therefore males tend to gravitate to those jobs. Most of the companies that participated in our study did not have formal recruitment pathways (i.e., human resource professionals, use of third-party headhunters). Instead, they favored the use of common job sites (e.g., Craigslist) to post open positions. Although the lack of formal recruitment pathways is likely more attributable to a lack of resources or low turnover rates within small companies, instead of disinterest, it means that companies are often limiting future candidates to personal contacts instead of attracting a diverse pool of applicants.

Organizational fit was another reoccurring theme that emerged in the research as an important factor for both employees and employers. The employer interview responses revealed that employers highly value “organizational fit” among their employees and stress the importance of determining fit during the hiring process. One employer said, “after the in-person interview, at that point we’re trying to get a feel for a cultural fit.” The analysis showed that most companies describe their work environments to be “casual”, “laid-back” and “familial” for all employees regardless of gender. However, survey results showed that the women surveyed do not feel as included at work as men do. Of the women who took the survey, 13 percent responded feeling “very inclusive” in their work environment, while 45 percent of men responded feeling the same. Additionally, three out of 8 women who responded to the survey discussed culture with their employer during the hiring process, but none of those women strongly felt that their culture matched that description once they were hired.

Finally, survey and interview responses showed that work life balance programs and mentorship were important but underutilized. It was clear in the survey section that although work-life balance programs were common at the private companies, participation and knowledge of such programs was low. The interviews revealed that although these programs existed, information was not always available and participation not necessarily encouraged. Additionally, it was evident from the interviews that these programs were often not geared toward women. Maternity leave and mentorship are examples of two programs that benefit women more than their male counterparts, but not all case study companies offered these programs. Finally, it became apparent that even when programs existed, there was a lack of formal program structuring, which could contribute to the lack of participation among IT employees.

V. Suggested Interventions

The results of the literature review and the case studies revealed three areas that were especially important to address. Three recommendations to small businesses have been identified that are feasible for employers and employees to implement into their work environments. The three recommendations were identified after careful analysis of the case study results, specifically when employee’s responses from the surveys did not align with their corresponding employer responses from the interviews to similar questions. For example, when employers post jobs online where most potential applicants search, but the majority of men find their IT jobs through this mechanism versus women. These recommendations are also identified in the research to be important to the recruitment and retention of women in IT positions.

1. reduce Job Posting Bias

One intervention necessary for mitigating barriers to attracting and keeping women in IT positions would be to reduce gender bias pervasive throughout job posting language.56 A primary challenge for women in regard to job posting language is that word choice does not promote feelings of belongingness to the company or the position. 57Women are less inclined to apply for jobs that convey an isolated work environment or individualized work culture, which is often what masculine job posting language conveys.58 For example, the words “analyze” and “determine” are usually perceived as masculine words while words like “understand” and “establish” are usually perceived to be feminine. All of these words have been used in job postings before, but it is important to recognize bias within them. The phrases below compare common language found in job postings: one that uses masculine words and one that might appeal more to women.

“Perform in a COMPETITIVE environment” vs. “Collaborates well in a SUPPORTIVE environment”

The employers who were interviewed in this study revealed how much they rely on job posting sites and similar avenues to promote open positions across the IT field. They rely heavily on these sites and the employees survey results show that individuals looking for positions rely on these sites as well. Of the women surveyed in this study, 13 percent found their current position online, compared

_________________

56 Gaucher, Danielle, Justin Friesen, and Aaron C. Kay. “Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality.” Journal of personality and social psychology 101.1 (2011)

57Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. “Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97.6 (2009): 1045-060. Print.

58 Gaucher, Danielle, Justin Friesen, and Aaron C. Kay. “Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality.” Journal of personality and social psychology 101.1 (2011)

FIGURE E-9 Traditional workspaces, as seen below, often reflect a situation where IT employees are located in a separate physical space from other employees.

to 48 percent of men. The language used in job postings is especially important as it what is used to explain the open position, describe what and who the company is looking for, and attract the potential candidate to the company.

Our case studies revealed that small companies with less than thirty employees rely heavily on trusted job sites, and these same companies also indicated that fewer women than men are applying for these open positions. In order to reduce gender biased language we suggest the use of gender neutral language. Small businesses, even those without formal H.R. departments or those that are not able to employ professional recruiters, can use a myriad of valuable resources available for constructing gender neutral language in their job postings. Companies can take advantage of organizations such as the Anita Borg Institute and National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT) that can provide examples of gender-neutral language and job postings. These resources are intended to educate and inform employees on how to construct postings, which will not deter women from IT positions.

Raising awareness around the gender bias is the first step for small businesses to carry out, ensuring that the employees responsible for hiring IT personnel are properly informed. Use of easily available tools, such as those described above, is the second step to educate employees on the phrases and words to use to avoid gender bias and will help remove some of the institutional barriers present in the recruitment of women to IT occupations. Often these resources or even trainings are available at low or no cost, which makes them an ideal application for small businesses.

2. Integrating Physical Space

The concept of ambient belonging explains the connection between physical environment and fitting in.59 The employers that participated in the case studies all valued fit among their employees. Employers in the case studies not only valued fit among their employees, but they also described the culture of their organizations to be fitting for women and men equally; describing the culture of their companies as, “communal, laid-back, like a family, casual.” However, the survey results reveal that only 3 out of 8 women discussed organizational culture with their current employers during their hiring process and none of them felt strongly that the culture matched the description they were given once they started employment.

FIGURE E-10 An example of an integrated workspace where IT employees sit among non-IT employees.

One company with 10-30 employees who participated in the case study described their workplace to be collaborative and flexible because their employees do not work in a cubicle environment. However, the same employer said that their programmers are segregated and sit together in a separate office, which is a common arrangement across employers (See Figure E-9). As the group is segregated from the main office, the employer could not say for sure but he assumed employees are comfortable in that environment and assumed if a woman were to start working there she would be fine.

Research has found that employees who do not feel that sense of belonging can be deterred from entering or remaining in a position.60 We propose an intervention which would integrate physical workspaces to reduce isolation among IT employees. An open workspace would reduce physical barriers between IT and non IT employees as well as between men and women. A more integrated workspace between IT and other employees will encourage forming informal networks between coworkers throughout the organization. Additionally, it can promote a more collaborative environment and increase flexibility. Physically integrating IT employees among non-IT employees via seat or desk assignment can lead to an increased sense of belonging and promote collaboration among employees regardless of position.

Integrating IT employees into the physical space is a feasible and cost-effective application that small business can execute. Half of the participating companies in the case study employed 30 or less employees. Arranging workspaces to encourage IT employees to sit among other departments is a feasible alteration (See Figure E-10 for a

_________________

59Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. “Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97.6 (2009): 1045-060. Print.

60Cheryan, Sapna, Victoria C. Plaut, Paul G. Davies, and Claude M. Steele. “Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97.6 (2009): 1045-060. Print.

sample arrangement). This improved sense of belonging can help to effectively reduce some barriers to recruitment and retention of qualified women in the IT world for small businesses.

3. Support Systems for Women

The absence of women from the IT fields results in a male-dominated environment, creating a cycle of affirmation that the industry is not a viable career for them. Women perceive the work to be difficult, isolated, and lacking social interaction.61 They conclude from preconceived stereotypes that they have very little in common with the people in the IT field and that they do not belong. The more they perceive the environment to be masculine, the less interested they are in it.62 These effects can be mitigated however, by linking female employees with mentors within the industry.63 Companies that hope to increase gender diversity and create workplace environments that reduce the high rates of female attrition from IT positions, can do so by actively promoting membership to professional IT associations and fostering the development of internal collegial relationships through the use of mentorship programs.

When companies are able to facilitate and create welcoming environments, women are more likely to advance and stay in their IT roles.64 Our study found that employees attributed participation in their company’s mentorship program to positively influencing their decision to stay in the industry. As such programs essentially serve a supportive role and mentors help facilitate women’s professional development. Mentors provided an outlet for employees to share best practices and learn tools to better deal with the daily challenges indicative of the field.65 About 83 percent of the employees surveyed stated that mentoring positively impacted their decision to stay in their IT role. Not a single responded felt that it negatively impacted their decision. However, more than half of the employees surveyed stated that such programs were not offered. For an industry that is projected to have the highest growth in comparison to any other sector, this is a missed opportunity for small businesses, but one that they can easily capitalize on.66

If resources are limited or there are personnel constraints that impede implementation of mentorship programs, small businesses can also actively promote membership to professional associations. They are widely accessible and a great alternative for small businesses looking to provide a supportive platform externally. Organizations such as NCWIT or Association for Women in Science (AWIS), are just two out of the dozens of associations that currently exist and can be very effective if the establishment of internal networks are not feasible. An initiative that can be undertaken outside of the work environment, it is a resource that does not require many inputs and can be an effective tool for women in IT.

VI. Limitations

Building upon the current literature, this study strove to identify these barriers within the context of small businesses. Given our focus, the findings cannot be generalized to medium and large companies although the interventions proposed could be effective throughout the industry. It is equally important to note that small businesses are defined by the Small Business Administration, as entities with 500 or less employees. The size of the participating companies within our study is not representative of all small businesses in the U.S. Our study disproportionately included companies that had less than 50 personnel. Once a company reaches a certain threshold, internal changes occur in relation to corporate systems and infrastructure. Implementing the suggested interventions becomes a bit more complex, as formal internal policies take precedence over employee preferences.

Due to the small sample size of participating companies and survey respondents, the findings cannot be interpreted as indicative of the entire IT industry. The number of IT employees within each company varied, as did the number of IT workers who eventually responded to the surveys. As a result, there was a small sample of female IT workers in comparison to the number of male respondents. While this could be reflective the overall lack of women in the industry, we lack the data to make this correlation. Other factors that affect the representation of women in IT, such as the geographic location of the company, recruiting strategy, and advert language for openings within the company, could not be examined and thus, were not taken into consideration.

This study also does not examine other factors that may impact the ability of small businesses to hire more women for IT roles, including factors such as contracting, resource constraints, and limited experience exercising IT industry strategies in the recruitment and retention of women.

_________________

61 Wentling, R.M., & Thomas, S. (2009). Workplace culture that hinders and assists the career development of women in information technology. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 25(1), 25-42.

62Cheryan, S. (2012). Understanding the paradox in math-related fields: Why do some gender gaps remain while others do not? Sex roles 66(3-4), 184-190.

63 Drury, Benjamin J., John O. Siy, and Sapna Cheryan. “When Do Female Role Models Benefit Women? The Importance of Differentiating Recruitment From Retention in STEM.” Psychological Inquiry: an International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory 22.4, 265-69.

64Roldan, Malu, Louise Soe, and Elaine K. Yakura. “Perceptions of Chilly IT Organizational Contexts and Their Effect on the Retention and Promotion of Women in IT.” Computer Personnel Research 2004. CPR 2004: Tucson.

65Ibid.

66Cheryan, S. 2012. Understanding the paradox in math-related fields: Why do some gender gaps remain while others do not? Sex Roles 66(3-4): 184-190.

VII. Implications for Further Research

This study attempts to provide specific and implementable solutions for employers to execute, however continued research is necessary to develop more robust interventions.

The conclusions in the literature review on the recruitment and retention of women in IT were largely derived from studies conducted in larger corporations. Given the market share of small and medium size businesses, it would be beneficial for future research to further examine these barriers. Additionally, most research views women as a homogeneous group. Further research should explore the unique differences among women including generational or cultural factors.

If further case studies were conducted on women in IT positions, another consideration that should be explored is the collection of data on where women go after they leave their current position. Additionally, collecting data that allows for a comparison between individual experiences at a large business versus a small business could provide unique insights into why women leave their current position.

VIII. Conclusion

Where large business can be rigid, small business can be more flexible and better able to quickly implement changes such as a new office layout and rewording job postings. Small businesses may not always have enough staff to support internal mentoring among colleagues, but they can partner with a wealth of external organizations that specialize in mentoring women in IT and related technical fields. Small businesses are at the epicenter of attracting and keeping more women in IT positions.

IX. Appendices

Appendix E-1. Frequently Asked Questions

Appendix E-2. Participant Consent Form

Appendix E-4. Interview Questions

Appendix E-1. Frequently Asked Questions

Promising Practices for Recruitment and Retention in the IT Workforce

Frequently Asked Questions

Who are you and what is this project?

We are a group of graduate students at the H. John Heinz III College at Carnegie Mellon University working on a capstone project for the National Academies. Our project will identify Promising Practices for Recruitment and Retention in the IT Workforce. As part of our research we are conducting case studies of small and medium size companies with IT Departments.

Why is my participation important?

Your response is valuable in helping to advance recruitment and retention strategies throughout IT departments across the country.

Who else are you interviewing during the course of this project?

Our study will conduct interviews and surveys with H.R. personnel, hiring managers and employees in IT Departments. We will be talking to a diverse group of companies in different industries across the country.

Will my answers be shared with my employer or my co-workers?

Protecting the employee-employer relationship is of utmost importance to us. Your survey responses will be kept anonymous. Individual survey responses will not be shared with your fellow employees or your employers.

What are you going to do with your findings?

Individual survey responses will be analyzed and will inform the conclusions for our study. Our final product will be presented at a careers pathways workshop for the National Academies.

What’s in it for me?

Your response contributes to the success of this project. We will provide you with our published report, in which we will outline promising practices for how companies across America can find and keep the best employees for the job.

Appendix E-2. Participant Consent Form

Promising Practices for the Recruitment and Retention in the IT Workforce

Consent to Participate in an Interview

Graduate students at the H. John Heinz III College at Carnegie Mellon University are working on a capstone project for the National Academies. The purpose of the project is to identify Promising Practices for the Recruitment and Retention in the IT Workforce. As part of our research we are conducting case studies of small and medium size companies with IT Departments. These case studies will consist of interviews with H.R. personnel and hiring managers as well as surveys with employees in the IT Departments. We will be talking to a diverse group of companies in different industries across the country. Individuals from these groups will be asked to participate in the interview. The interview will inquire about the company’s recruitment processes and retention strategies. No personally identifying information will be collected during the interview.

The students will conduct all interviews. The interviewer will take hand written notes as well as record the interview electronically. We expect interviews to take no more than thirty minutes. One week after the interview we will send you a copy of the interview notes that you can correct or modify. Individual survey responses will be kept anonymous. They will be analyzed into one collective report.

The information you provide will be invaluable in helping to advance recruitment and retention strategies throughout IT departments across the country. Your response contributes to the success of this project. We will provide you with our published report, which will outline promising practices for how companies across America can find and keep the best employees for the job.

Taking part in this evaluation is completely voluntary. There is no penalty if you choose not to participate in the interview and your relationship with Carnegie Mellon University or any other stakeholders affiliated will not be affected.

Participant: I have read this consent form. I understand the information and have no remaining questions. I understand I will be provided with a signed copy of this form. My signature of this consent form indicates that I agree to take part in this interview.

| Print Name ____________________ | Date: _________________ |

| Signature ______________________ |

Interviewer: I have fully explained to the participant the nature and purpose of the evaluation interview. I have answered any and all questions to the best of my ability.

| Print Name: _______________________ | Date: ______________ |

| Signature: _________________________ |

Appendix E-4. Interview Questions

CMU Case Study Employer Questionnaire

Estimated Time Commitment: 15-20 Minutes

1. How many employees are in your company?

a. What is the gender breakdown within that?

b. How many IT employees do you have, and what is the gender breakdown?

2. What is the daily workload for your IT workers or IT department like?

a. Do you require employees to be on call?

b. If so, how often?

3. For your most recently posted technical position, how many people applied?

a. Out of the total, how many were women?

4. Could you describe briefly what your recruitment process is and what that entails?

a. How many of your employees are involved in the recruitment process?

b. Do you have any special campaigns or initiatives that are targeted toward women?

5. Could you describe or would you be able to provide us with a list of what benefits or employee development initiatives your company offers?

a. For example, mentoring, alternative work schedules, daycare, etc…

6. Do you have any initiatives that you have implemented which specifically target improving and recruitment and retention of women?

a. If so, what are they?

b. Are any of these specifically aimed at improving recruitment and retention of women in IT positions or technical roles?

c. Which of these would you consider most effective?

7. Can you describe the culture here, so that I could get a sense of what some of the daily interactions entail?

8. Did you have any questions for me or any other comments that you would like to make?

Appendix E-5. Participant Company Descriptions

Employer A involves the development of a unique search engine specific to their industry and offers a marketplace allowing sellers and buyers in real estate to more easily conduct searches. Headquartered in Pittsburgh, the company is 3 to 5 years old. The business has fewer than 20 employees, 11 of which are considered IT employees. None of the IT employees are women. This company is considered “tech-focused” by this study.

Employer B offers “uniquely created e-commerce services,” some of which include client branding capabilities, digital storage, and marketplace capabilities. Located near Greenville, South Carolina (the state’s third largest urban area), the company is 12-15 years old and has fewer than 20 employees, 4 of which the company considers IT employees; none of the IT employees are women. This company is considered “tech-focused” by this study.

Employer C, based near Los Angeles, provides services such as software development, web hosting, web development, and e-commerce web design. The company is 12-15 years old and has fewer than 20 employees, 11 of which are considered IT employees. One of the IT employees is a woman. This company is considered “tech-focused” by this study.

Employer D is a law firm headquartered in Pittsburgh. The company is more than 30 years old and was not a considered a “small business” in our study as it has more than 500 employees, 64 of which the company considers IT employees. Nineteen of the IT employees are women.

Employer E is a data and content company serving a specific industry. The company has corporate offices around the globe, with headquarters in Chicago. The company is approximately 30 years old and has 150-175 employees, 11 of which the company considers to be IT employees; one of the IT employees is a woman. This company is considered “tech-focused” by this study.