Higher Education and Ongoing Professional Learning

This chapter considers higher education and ongoing professional learning for educators who provide care and education for children from birth through age 8. It begins by reviewing higher education programs that prepare these professionals for practice, and then turns to opportunities for professional learning during ongoing practice.

This section examines formal education and coursework for educators of children birth through age 8 that takes place in institutions of higher education and is designed to lead to a degree (associate’s, bachelor’s, or graduate) or certificate. Although this is often referred to as “preparation” or “preservice” education, it is sometimes undertaken during ongoing practice, especially by professionals practicing in early care and education settings outside of elementary schools or for those pursuing advanced degrees.

Teaching is one of the most common occupations in the United States (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014; Peterson et al., 2009), yet as a nation the United States lacks a common vision for or standardization of how to prepare educators. This lack of standardization has influenced perceptions of the occupation, as well as policies and practices for teacher preparation. The lack of standardization and its effects become even more striking when viewed in light of the broad variations in the preparation of educators across professional roles and settings for children birth through age 8. Compared with educators teaching in childcare centers, early childhood programs, and preschools outside of public school

systems, early elementary educators teaching in public elementary schools engage in a comparatively structured, established, and regulated system. Yet neither “system” is producing sufficient numbers of educators who are well qualified to support the early learning of children from birth through age 8, and the diffuse and variable nature of the preparation of educators of young children presents a challenge to the development and implementation of policy approaches that will lead to meaningful change.

This section first gives an overview of the current landscape of education pathways and expectations for care and education professionals across roles and settings, and then places this current state in the context of the historical development of expectations for these roles. Subsequent subsections then consider factors that contribute to the availability and quality of professional learning in higher education settings for these care and education professionals.

Overview of Current Education Pathways for Educators of Children from Birth Through Age 8

Preparation pathways for educators vary, as do governance, oversight, standards, and funding structures (NRC, 2010). Different standards and requirements for qualification to practice as an educator are one of the major drivers of differences in the educational pathways among different professional roles, especially between those who teach in elementary school settings (which can be prekindergarten through third grade or kindergarten through third grade, depending on the school system) and those who teach in settings outside of elementary school systems, such as early education programs or preschools, childcare centers, and family childcare (Whitebook, 2014).

For educators in kindergarten through third grade (and for prekindergarten teachers in some school systems), “teacher preparation” refers to preservice education in a degree-granting program and subsequent licensure that are typically required before employment. Teacher preparation programs often include coursework requirements and student teaching experiences, required by policy in most states (Loeb et al., 2009). Attainment of a degree often is followed by induction or mentoring programs for new teachers (Whitebook, 2014). Candidates for teaching in the elementary grades must have a bachelor’s degree and state certification, but there remains a lack of standardization and consistent quality in preparation programs, including those offered by traditional institutes of higher education, community colleges, and alternative-route programs such as Teach For America (Whitebook et al., 2009).

Standards for training of educators in early childhood programs and childcare are even more variable than those for elementary teachers, be-

ing set by each state with the exception of Head Start and Military Child Care, which establish uniform national requirements for teachers and other personnel (Whitebook, 2014). Unlike educators in elementary schools, many of these educators do not participate in preservice education; their participation in formal education or training for their profession may not commence until after they have become employed in the field. As a result, for many of these educators, their first job serves as their opportunity for “practice teaching,” but rarely with a formal induction period or structure of close supervision with an educational aim (Whitebook et al., 2012). However, as educational requirements are increasing in programs such as Head Start, in publicly funded prekindergarten, and in state quality rating and improvement systems, educators in professional roles outside of the elementary grades are increasingly attending college or university programs to complete required credits or to earn degrees, either before working or while employed (Whitebook, 2014).

Historical Perspective on Educator Preparation in the United States

As described in Chapter 1, education for children from birth through age 8 in the United States has its roots in five distinct traditions: (1) childcare; (2) nursery schools; (3) kindergartens; (4) compensatory education (to compensate for unfavorable developmental or environmental circumstances experienced by children, particularly those from low-income families); and (5) compulsory education at the primary level or early elementary school. For many years, these initiatives proceeded along relatively separate paths, and each has had its own historical evolution in pathways to professional learning.

As efforts emerge to help these traditions converge, the different philosophies and historical perspectives associated with each sometimes complement one another and sometimes clash. As context for understanding the current status of preparation and training for these professional roles, Appendix D provides timelines briefly describing these different histories. The following subsections summarize some key themes in the evolution of expectations for training and professional learning over time.

Professional Silos

Preparation for roles in early childhood and for roles in elementary grades have existed in silos from the beginning, with some minor efforts at integration over time. One transition that occurred is that kindergarten shifted from being treated primarily as similar to other early childhood settings to becoming recognized as part of the country’s public school system. Kindergarten became integrated into public education, and with it, train-

ing for kindergarten teachers. A similar shift may be starting to occur as prekindergarten becomes incorporated into public education in some states and municipalities.

Aims of Professional Practice

Training for professional roles in early childhood, including kindergarten teachers, has historically taken a broad perspective on the goals of child learning and development and therefore on the skills and knowledge educators need. Preparation for these professionals has commonly focused on supporting children’s emerging development by providing experiences related to physical, social, emotional, behavioral, language, and cognitive processes and skills. Although the distinction is not absolute, preparation programs for public school teachers from early on focused on preparing them to teach academics and “knowledge.”

Educational Expectations and Perceived Status or Prestige

Educational expectations and perceived status or prestige have fluctuated by professional role over time. Nursery school teachers initially were expected to have 4-year degrees and to operate as equals among other professionals, and childcare providers also were required historically to have higher education. However, a shift occurred over time to lower expectations for early childhood educators. On the other hand, elementary school teachers were initially expected to obtain less training and education than secondary school teachers, although as they were integrated into public school systems, those expectations gradually increased. These divergent expectations and perceptions of prestige between early childhood and elementary and between elementary and secondary educators remain today. Society (the general public, policy makers, and even care and education professionals themselves) has tended to perceive working with younger children as less demanding and prestigious work, a perception that runs counter to the science of child development and early learning presented in Part II.

Conclusion About Divergence Between Early Childhood and Elementary School Educators

Significant differences exist in the settings, professional identity, expected knowledge and competencies, licensure and credentialing, organizational supports, and professional learning resources for professionals who work in roles and settings such as family childcare and childcare centers compared with those who work in elementary school settings. This divergence is dissonant with what the science of early

learning reveals about the enormously formative growth in early learning that is already occurring from birth and about the core competencies that all care and education professionals should possess. Reducing this dissonance will require major changes to policies and practices that have evolved through historical trends and are entrenched in current systems.

Characteristics of Programs in Higher Education

Because of the lack of uniformity in and comprehensive data on teacher preparation, it is difficult to clearly delineate different pathways for educators and provide precise characteristics of each. Paralleling variability in expectations for and participation in higher education across professional roles is a great deal of variability across institutions and programs. Policies that set qualification requirements for practice (such as licensure or credentialing and hiring policies) do not always distinguish which of those pathways yield the knowledge and competencies needed by care and education professionals to do their jobs well. Several general characteristics contribute to how these programs—whether in 2- or 4-year institutions—prepare educators. The following subsections address several of these key characteristics, including the current institutional fragmentation of educator training in higher education, the content of coursework, field-based learning experiences, admission requirements, faculty characteristics, diversity of faculty and students, access to higher education, and relationships between 2- and 4-year institutions.

Institutional Fragmentation

Wide variation exists both among and within institutions that educate students for careers in care and education. This lack of consistency creates a highly fragmented approach to preparing educators for practice. First, a number of different kinds of institutions offer programs for professional roles in care and education, including institutions of higher education at the 2-year, 4-year, and graduate levels, as well as other institutions that administer alternative certification pathways for educators. These various institutions have evolved in their purposes over time (see Table 9-1).

Within this array of institutions exist a multitude of degree and certificate programs intended to prepare professionals for various job titles and roles in working with children from birth through age 8. These programs are called by various names and are organized in various ways, for example,

- by role (e.g., teachers, administrators, program directors, coordinators, principals, superintendents, paraprofessionals, aides, assistant

-

teachers, after-school care providers, early intervention specialists, special education teachers, school therapists/counselors);

- by age range or grade level (e.g., birth-3, 3-5, prekindergarten to third grade, kindergarten to fifth grade, kindergarten to eighth grade);

- by setting (e.g., Head Start, childcare, public school); and

- by academic discipline, school, and department (e.g., education, health and human services, social and/or behavioral sciences such as developmental psychology, professional studies, liberal arts, agricultural sciences, and technology) (Saluja et al., 2002).

Approaches used in preparation programs for elementary school educators vary, although these approaches are more consistent than those of programs for care and education professionals outside of elementary school settings. For educators preparing to teach at the elementary level in public schools or other school systems,

- all states have schools of education, located in 4-year universities and colleges, that are charged with preparing teachers (Levine, 2013);

- all states offer alternative pathways for teacher preparation (Levine, 2013); and

- all teacher preparation programs include some clinical or student teaching experience (Levine, 2013).

For educators preparing to practice in early childhood settings outside of elementary schools or public school systems, early childhood–related higher education degree programs are found in both 2- and 4-year colleges, but the majority of departments designated explicitly as early childhood are found in 2-year institutions (Whitebook et al., 2012).

In addition to the variability across institutions and across professional roles, fragmentation results from organizational variability within institutions. It is common to have multiple programs focused on professions related to early childhood that are operating on the same campus but are scattered across the same institution, housed in separate departments with different expectations and requirements (Whitebook and Ryan, 2011).

Content of Coursework

Ultimately, the aim of coursework for prospective care and education professionals is to help them both acquire knowledge and be capable of integrating that knowledge into competencies that translate into their practices and behaviors with children in learning environments. One of

TABLE 9-1 Historical Institutional Traditions for Teacher Education

| Institution | Form | Elements/Themes | Primary Clientele |

| State normal schools (1839-1940s) and state teachers colleges (1920s-1940s) | 2-year course of study: pedagogy and review of subjects learned in elementary and high school and pedagogy |

|

Elementary teachers |

| Liberal arts colleges (1800s-present) | Embedded in 4-year baccalaureate program |

|

Secondary teachers |

| University schools of education (1900s-present) | Graduate programs |

|

Education leaders |

SOURCE: Adapted from Feiman-Nemser, 2012.

the greatest challenges in the field is a lack of widespread implementation of agreed-upon standards for what constitutes a high-quality educator preparation program. The current high variability in program content and requirements cannot be expected to produce consistently effective results.

The content of a course of study in a higher education program for prospective educators can be informed by multiple sources, including institutional leadership and faculty, state learning goals and standards, state teaching standards, criteria in state laws and policies for licensure or certification (discussed in more detail later in this chapter), state rules that govern higher education institutions, and voluntary accrediting bodies often organized by profession (also discussed in more detail later in this chapter). Degree programs vary in the content of required coursework and in the age ranges included for pedagogical strategies and student teaching. Elementary school educators typically are required to complete a course of study that aligns with state certification or licensure requirements, providing some benchmarks for consistency, yet programs continue to vary widely in content and in the extent to which they adequately address the teaching of children in the early elementary years. Early childhood higher education programs have historically been even less consistent, with courses of study within one of several disciplines being considered acceptable, although efforts to expand accreditation of these programs are under way, described later in this chapter (Maxwell et al., 2006; Whitebook et al., 2012). As many care and education professionals enter the field from a wide array of educational backgrounds, another challenge the field faces is identifying ways for all professionals to receive the content of this coursework, especially those who do not enter the field through traditional programs in institutions of higher education (Whitebook et al., 2009).

Formal coursework topics commonly, but not consistently or comprehensively, required in educator preparation programs at the associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s levels, as well as for the Child Development Associate credential, can include the following: education and care of children across the age continuum, including dual language learners and young children with disabilities; interactions with children and families from ethnically and culturally diverse backgrounds; assessment/observation of young children; literacy, language, and numeracy instructional strategies; social and emotional development; physical health and motor development; and classroom and behavioral management (Maxwell et al., 2006).

Formal coursework content in programs that prepare educators fall into three categories: foundational theories of development and learning, subject-matter content, and methods of teaching and pedagogy (both general and specific to subject matter) (Whitebook et al., 2009). Despite the wide array of courses, curricula often do not delve deeply enough into the material to give students a profound understanding of it (Bornfreund,

2011). Child development is important core knowledge for care and education professionals, yet in many programs, courses focused on the science of child development are either not offered or offered only at the introductory level (Bornfreund, 2011). A further challenge faced by programs is how to link child development to pedagogy to help prospective educators learn how to apply developmentally appropriate practices in the classroom. Research has found that many educators are unable to identify what factors impact the quality of their teaching (Whitebook et al., 2009). Efforts of preparation programs to train educators to teach culturally, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse students also are limited, and many teachers do not learn to set aside their own biases in practice (Whitebook et al., 2009). Furthermore, while courses focused on interacting with families are common in early childhood teacher preparation programs, they are less common in K-5 programs (Bornfreund, 2011). A review of course content across 1,179 teacher preparation programs in the United States revealed several gaps in formal coursework. For example, only a small number of programs required any coursework focused on bilingual children, program administration, and adult learning, even at the master’s level (Maxwell et al., 2006).

Field-Based Learning Experience

Field experience, such as student teaching and practicums or field placements, is required in 38 states for public elementary school teaching candidates (Maxwell et al., 2006; Whitebook et al., 2009). In a 2006 survey of early education preparation programs, approximately 96 percent of associate’s and bachelor’s degree programs required field placements (Maxwell et al., 2006). Yet states have not implemented specific standards for this experience regarding setting, length of placement, and supervision nor is there a standard for what content should be covered in such experience (Maxwell et al., 2006; Whitebook and Ryan, 2011; Whitebook et al., 2009). This leaves room for the focus by default to be finding a placement and completing the required hours rather than the quality of the field-based learning experience. In the same 2006 survey of early education preparation programs, the content of field placements ranged to include care and education of infants and toddlers and preschool-aged children, care and education of young children with disabilities, family engagement, and working with bilingual children. The fewest number of programs required a practicum involving working with bilingual children (Maxwell et al., 2006). For the many teachers of children in settings outside of public school systems who enter the workplace without prior coursework or formal educational background, field experience is acquired on the job. These early care and education professionals often work without the guidance associated with a

field placement as part of a training program, such as formal observations, reflective practice, and reflective supervision (Whitebook et al., 2009).

The ideal practicum experience should be completed alongside formal coursework so prospective educators can apply what they are learning to their practice (Whitebook et al., 2009). Given that fieldwork often is conducted after the completion of formal coursework, during a candidate’s final term in school, there are few opportunities to make this connection consistently over the course of their degree program (Bornfreund, 2011). Although field placements are considered one of the most important elements of educator preparation, the experience varies, and many prospective educators acquire no real practice in the classroom with effective teachers (Bornfreund, 2011).

There are also opportunities to provide prospective educators with supplemental experiences that include working with individual students and small groups or observing ongoing classroom instruction (Bornfreund, 2011; Whitebook et al., 2009). In addition, given the importance of family engagement as a professional competency, it may be worth considering expanding field experiences to include participating in home visits and other engagement with families (Whitebook et al., 2009).

Finding high-quality field placements can be a challenge for educator preparation programs, although some believe there are opportunities for reflection and learning even when practicums are completed in poor-quality settings (Whitebook et al., 2009). Another challenge is that arranging for supervised practicums and completing student teaching requirements frequently pose scheduling and compensation challenges for those students who are completing degree programs while also working full time (Whitebook et al., 2011).

Perspectives from the Field

A critical skill for educators in all settings is the ability to apply what is learned in formal coursework to real-world practice settings. This necessary skill highlights the importance of integrating field experiences throughout formal education or certification programs.

Field placements in diverse settings are also one opportunity to train educators in areas such as working with diverse populations of students, cultural sensitivity, and family engagement.

————————

See Appendix C for additional highlights from interviews.

Admission Requirements

Admission requirements for higher education programs that prepare educators are often minimal, often involving a minimum grade point average and selected course prerequisites. These limited requirements may lead to a lack of selectivity among applicants, as most who apply are offered admission. This is in contrast with other fields, such as business or medicine, which have highly selective admission standards (Bornfreund, 2011).

Researchers recognize that qualities and dispositions that make individuals strong educators may not be reflected in grades and test scores. A 2008 review identified such traits as exhibiting fairness, empathy, enthusiasm, thoughtfulness, and respectfulness (Rike and Sharp, 2008). Incorporating interviews, writing samples, and recommendations as part of the application process can be a step toward strengthening the selection of applicants and recognizing a wider range of important traits that reflect the potential for quality professional practice (Bornfreund, 2011).

A 2003 study, for example, assessed the effectiveness of group-assessment interviews as a component of admissions criteria for teacher education programs. The group-assessment procedure consisted of a 90-minute interview with eight teacher candidates and two trained evaluators. During the session, candidates engaged in a group discussion, participated in problem-solving activities, and completed a self-assessment. This process was used to evaluate candidates’ communication, interpersonal, and leadership skills. The study found that the group-assessment interview procedure could more strongly predict performance in student teaching than academic criteria (grades and standardized tests) (Byrnes et al., 2003).

Faculty Characteristics

The faculty in a training program for educators are an important factor in the program’s quality. Concerns over the composition of faculty have been raised in multiple reports in the past decade, particularly for programs that train educators for practice in early childhood settings outside of elementary school systems (Bornfreund, 2011). Professionals preparing the early childhood workforce ideally are trained academically, having received a graduate degree, and have the practical experience needed to prepare prospective educators to meet standards for professional competency (NAEYC, 2011b).

One challenge is insufficient faculty members in small programs or institutions, such that the breadth and depth needed for a high-quality preparation program are lacking. For example, a shortage of faculty has been linked to a shortage of qualified and effective special education teachers (Smith et al., 2001). The Special Education Faculty Needs Assessment

project found that nearly half of advertised positions were vacant because of retirement. The turnover rate for educators in special education programs is 21 percent, and the turnover rate for faculty in institutions of higher education is double this number (Smith et al., 2011).

Another challenge is the use of part-time faculty. A 2006 study found that more than half of the faculty in early childhood programs across 2- and 4-year institutions of higher education were employed part time. The number and percentage of part-time faculty was higher at 2-year institutions (69 percent) than at 4-year institutions (42 percent) (Early and Winton, 2001; Maxwell et al., 2006). In another study, 42 early childhood teacher preparation programs had an average of 3.5 full-time faculty members, supported by adjuncts who, because of their status, were ineligible for tenure (Johnson et al., 2010). Early childhood programs also tend to make greater use of part-time faculty than their institutions as a whole (Early and Winton, 2001). The reliance on adjuncts and part-time faculty to support early childhood educator preparation programs can lead to inconsistent teaching practices, as well as long work hours, more administrative tasks, low salaries, and few benefits for faculty, all of which can negatively affect student learning (Early and Winton, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010). In addition, part-time status limits the time during which faculty are available to meet the needs of students seeking additional guidance and mentorship outside the classroom (Early and Winton, 2001).

The preparedness of faculty is a concern as well; variability in their expected qualifications and inconsistencies in their expertise and experience may lead to variations in program quality. Qualifications for faculty in early childhood educator preparation programs vary by program and position title. Job requirements for these types of positions commonly include experience teaching courses related to education in such areas as curriculum development, student guidance, and teacher education (O*Net Online, 2011). Programs find that faculty members may lack expertise in specific content areas, including early childhood education (Bornfreund, 2011). In addition, faculty with prior experience working directly with children in early childhood settings are found less often in 4-year than in 2-year institutions (Maxwell et al., 2006). Table 9-2 provides some recent examples of faculty qualification requirements. It shows that faculty may be required to hold a bachelor’s or graduate degree in a related field, and often are required to have experience teaching adults and/or direct experience working with children in early childhood settings, as either an educator or an administrator. Faculty members often are required to have experience working with diverse populations and diverse learners. Some position descriptions include an interest in research and scholarly activities; commitment to social justice; and knowledge of program approval, state licensure, and accreditation standards.

TABLE 9-2 Illustrative Examples of Requirements for Faculty Positions

| Position Title | Requirements |

| Adjunct Instructor, Early Childhood Education-Administrator Credential (HigherEdJobs, 2014a) |

Required

|

Desired

|

|

| Part-Time Child Development Instructor (HigherEdJobs, 2014c) |

Required

|

| Position Title | Requirements |

| Urban Early Childhood/Elementary Education Faculty (full time) (HigherEdJobs, 2014d) |

Required

|

Desired

|

|

| Position Title | Requirements |

| Department of Elementary and Early Childhood Education, Assistant Professor-generalist (full time) (HigherEdJobs, 2014b) |

Required

|

Desired

|

|

A promising practice for ameliorating some faculty-related issues is the appointment of full-time faculty, although often nontenured, who focus on instruction, working closely with students, and supervision of field experiences rather than on research activities (Ernst et al., 2005). Professors of practice are part of the faculty in the University of California’s Schools of Education, for example, and it is their responsibility to provide prospective educators with a full understanding of skills needed to practice in the field, as well as the opportunity to interact with knowledgeable and experienced professionals (University of California, San Diego, 2013). Although the number of professors of practice appointed as full-time faculty often is low compared with the numbers of academic and research faculty, their contribution can be highly valuable because of the competencies they have developed through their practical experience and expertise in the field (Ernst et al., 2005).

Diversity of Faculty and Students

Another challenge for programs that prepare educators is the lack of diversity among faculty members, whose composition does not tend to reflect the teacher candidates in preparation programs or young children in early childhood programs. A 2006 report on faculty and student characteristics reflected a lack of diversity among faculty, and a 2010 report likewise found that more than one-third of institutes of higher education surveyed had no faculty members of color or minority ethnicity. Specifically in early childhood educator preparation programs, most faculty were white non-Hispanic (Bornfreund, 2011; Johnson et al., 2010; Maxwell et al., 2006). This lack of diversity can be a limitation for creating a diverse workforce, particularly in leadership and director positions (Early and Winton, 2001). Many program chairs and directors acknowledge that without racial and ethnic diversity among faculty, students in preparation programs and those seeking advanced degrees may have few role models in this field (Early and Winton, 2001).

The composition of children and families served by elementary schools and early childhood settings has shifted dramatically over the last two decades, with significant growth in immigrant and non-English-speaking families. Projections are that by 2050, about half of all children and adolescents under 17 in the United States will be Hispanic (36 percent), Asian (6 percent), or multiracial (7 percent) (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2013; National Partnership for Teaching in At-Risk Schools, 2005). Whitebook (2014, p. 8) describes the issue thus:

The increasing diversity of the child population requires changes in teacher preparation and professional development at all levels of education to ensure that teachers are knowledgeable and skilled in meeting the needs of children from a range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. It also requires greater attention to the issues surrounding the racial/ethnic and linguistic backgrounds of the teacher workforce in both ECE [early care and education] and K-12 sectors. Teachers representing minority groups are invaluable in providing positive role models for all children and responding to the needs of minority children. For example, minority teachers typically hold higher expectations for minority children, and are less likely to misdiagnose them as special education students. Minority teachers often are more attuned to the challenges related to poverty, racism and immigration status that many children of color face in their communities (Learning Point Associates, 2005). For children younger than five, teachers who speak the home language of the young children are a critical asset in promoting their school readiness, engaging with families, and communicating with children who are learning English as a second language. (García, 2005)

Different care and education settings face somewhat different challenges with respect to diversity. The early care and education workforce is more racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse than the elementary school workforce (see Table 9-3). In one survey, 84 percent of K-12 teachers were white (Feistritzer, 2011), while studies have found that one-third to one-half of early care and education teachers are people of color (Child Care Services Association, 2013; NSECE, 2011; Whitebook et al., 2006).1 However, there is stratification by position along the dimensions of race, ethnicity, and language, with lead teachers and directors more likely to be monolingual English speakers and white (Whitebook et al., 2008a). Thus, for elementary schools, recruiting and retaining minority educators is the primary challenge (Ingersoll and May, 2011). For early childhood settings, the challenges are maintaining a culturally and linguistically diverse workforce even with increasing qualification requirements and reducing stratification among lead educators and program leaders (Whitebook, 2014).

Recruiting diverse faculty and prospective educators now will help create a diverse body of teachers that resembles the population of young children they teach (Maxwell et al., 2006). The NAEYC and the Society for Research in Child Development have made recommendations to work toward creating a diverse group of professionals who prepare educators (NAEYC, 2011b). There are examples of initiatives aimed at helping to increase racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity among early care and education teachers by supporting their access to higher education and success in attaining degrees (Whitebook et al., 2008b, 2013).

Access to Higher Education

The demographics of levels of higher education among care and education professionals reflect both expectations for and access to higher education (see Table 9-3). The trends closely follow the differing educational expectations for the different categories of professional roles. Elementary school teachers are all college educated, with nearly half having earned an advanced degree (Feistritzer, 2011). By contrast, the education levels of educators working with children aged 3-5 in center-based settings may have a bachelor’s degree or higher, an associate’s degree, some college, or a high school education or less. Those working with infants and toddlers cover a similar range, but with a greater percentage of them with less education

_____________

1 For example, a statewide study of California’s early care and education (ECE) workforce found that 58 percent of family childcare providers, 47 percent of center teachers, and 63 percent of center assistant teachers were people of color, compared with 26 percent of K-12 teachers (Whitebook et al., 2006). In 2012 in North Carolina, for example, just under half of center-based ECE teaching staff (49 percent) were people of color. Slightly fewer center directors (44 percent) were people of color (Child Care Services Association, 2013).

TABLE 9-3 Demographic Characteristics for Educators in Early Elementary and Early Childhood Care and Education Settings

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings |

| Teachers are typically female, represent a range of age groups, and are predominantly white. | Teachers are almost exclusively female, represent a range of age groups, and are ethnically diverse. |

As of 2010,

(Feistritzer, 2011) |

As of 2007, for educators working in Head Start,b

(Aikens et al., 2010; NSECE, 2011) In a statewide study of California’s early care and education workforce, people of color made up 58 percent of family childcare providers, 47 percent of center teachers, and 63 percent of center assistant teachers (Whitebook et al., 2006). In 2012 in North Carolina, 49 percent of center-based teaching staff and 44 percent of center directors were people of color. Almost all were women (Child Care Services Association, 2013). |

In 2011,

(Feistritzer, 2011) |

In 2012, for educators working with children aged 3-5 in center-based settings,

For educators working with infants and toddlers aged 0-3,

|

a The National Center for Education Information surveyed 2,500 randomly selected K-12 public school teachers from Market Data Retrieval’s database of teachers (Feistritzer, 2011).

b No comparable national data are available for educators in state-funded prekindergarten or other early childhood center-based settings. The forthcoming National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) (Aikens et al., 2010; NSECE, 2011) will provide information on gender, age, ethnicity, and language.

c The NSECE is based on more than 10,000 questionnaires completed in 2012.

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

(NSECE, 2013). As a result of the emergence of statutory requirements for educators in Head Start and prekindergarten to have a college degree, those working on those settings have become better represented among the more highly educated.

Variables that influence access to higher education programs include, for example, geographic access, affordability, program flexibility, program focus/content, and program length. The availability of financial support (such as tuition reimbursement, scholarships, Pell grants, Teacher Education and Compensation Helps [T.E.A.C.H.] scholarships, and Office of Special Education Programs) is one way to increase access. Another is to address the challenges of succeeding in higher education programs through such support as counseling, tutoring, and cohort models.

Perspectives from the Field

Grants, scholarships, and tuition and loan forgiveness programs are key to making formal coursework in a higher education setting more accessible to larger portions of the workforce for children birth through age 8. In addition to cost, time and geographic accessibility are also barriers.

For a family childcare educator, for example, long days, the responsibilities of owning and operating a business, and the need to arrange for a substitute are all challenges to pursuing higher education.

————————

See Appendix C for additional highlights from interviews.

Relationships Between 2- and 4-Year Institutions

Community colleges play a key role in preparing educators for degrees and certifications. In some cases, associate’s degree or certificate programs are completed entirely within a community college’s system. In addition, students often take general education courses, which may include teacher education, at community colleges before transferring to 4-year institutions. Students also may earn their teacher license by pursuing postbaccalaureate courses through a community college, usually on a noncredit basis. Another option available through some community colleges is a baccalaureate program. These programs maintain flexibility to meet the needs of students (Coulter and Vandal, 2007).

The ability to transfer credits from a community college to a 4-year institution can be hampered or facilitated by the structure of articulation agreements between these two types of institutions. Articulation agreements

link community colleges to 4-year institutions and provide continuity for the role of community colleges in educator preparation. The agreements may include such features as a common course numbering system or a joint admission program allowing for easy transitions between institutions. However, they are often limited by a top-down system in which articulation effort is controlled by the 4-year university. Strengthened collaboration between the two types of institutions is one way to establish educator preparation as a process that includes the community college system (Coulter and Vandal, 2007).

Alternative Pathways for Educating Educators

Alternative programs provide individuals who have previously received a bachelor’s degree outside of the field of education with formal coursework in education, job training, and support and mentoring in the classroom (U.S. Department of Education and Office of Postsecondary Education, 2013). These programs have become more common over the past 30 years. In 1985, fewer than 300 individuals became certified teachers through alternative programs; by 2006, this number had increased to just over 50,000 (Feistritzer and Haar, 2008). Although the majority of teaching candidates participate in traditional teaching programs, approximately 87,000 students were enrolled in alternative programs in 2009-2010 (U.S. Department of Education and Office of Postsecondary Education, 2013). The push for alternative pathways to teacher certification began as a solution to an increasing number of students enrolling in schools and a shortage due to teachers’ retiring and otherwise leaving the profession, leaving a need for more than 2 million new teachers in 10 years (Feistritzer and Haar, 2008; Johnson et al., 2005). These programs also help meet the increasing demand for diversity of educators as well as the need for educators with certain subject-matter knowledge (Alhamisi, 2008).

The Teach For America program is an example of an alternative pathway to teacher certification that recruits and trains new college graduates to teach in schools in vulnerable and high-risk communities. Teach For America launched an Early Childhood Education initiative in 2006, recognizing the need to ensure that all children have access to high-quality prekindergarten education. Prospective educators are provided with summer preservice training, regional induction, and regional orientation, as well as in-service virtual and in-person coaching. Since its launch, Teach For America has placed more than 1,000 new teachers in prekindergarten programs throughout the nation (Teach For America Inc., 2015).

The U.S. Department of Education identified several elements of effectiveness for these programs, including quality recruitment processes and selection criteria and screening of applicants. Applicant screening, often a

multistep process, includes a minimum grade point average and submission of writing samples, interviews with a selection committee, and sample lessons. Effective alternative programs also provide flexibility to meet the needs of their students, such as a shortened or fast-track program and evening or weekend classes to minimize any loss of income, as well as assistance with job placement. They also provide support to their students, including supervision on the job, mentoring, and opportunities for support from their cohort (U.S. Department of Education Office of Innovation and Improvement, 2004).

Conclusions About Higher Education Programs for Educators

The education that is available and expected for educators of children from birth through age 8 varies widely for different professionals based on role, ages of children served, and practice setting even though these candidates will have similar responsibilities for young children. Each of the different “worlds” that result from this variability has different values and priorities, different communities, different pathways for entering higher education, and different research bases. As a result, programs lack a consistent orientation and are extremely variable and fragmented across and within institutions. This lack of consistency has important implications for how educators are trained to work with children:

- There is a lack of widespread implementation of agreed-upon standards that guide program design, such as curriculum content, pedagogy, intensity of field-based learning experiences, and duration of study.

- There is a lack of strategies for ensuring that care and education professionals across settings and roles have access to high-quality higher education programs that leads them to acquire and apply in practice the core body of knowledge and competencies they need.

For higher-quality programs that are better matched to the competencies required for professional practice in both early childhood settings and early elementary settings, the following improvements are needed to content, curriculum, and pedagogy:

- Educators of children from birth through age 8 need to be taught instructional and assessment strategies that are informed by research on child development and early learning.

- These educators need to be taught learning trajectories specific to particular content areas, including the content, children’s learning

-

of and thinking about this content, and how to provide experiences integrating this content into curricula and teaching practices.

- These educators need high-quality field placements that build instructional competencies and also allow them to gain experience working with diverse populations of children and families.

The lack of valid and reliable data collection and measurement strategies has resulted in limited information about the content knowledge and pedagogical approaches that lead to effective higher education programs for educators.

Illustrative Examples of Higher Education Programs with a Birth Through Age 8 Orientation

The issue of quality in higher education extends to how well care and education professionals are equipped with the knowledge and competencies needed across professional roles and settings to support continuity in high-quality learning experiences for children from birth through age 8. Therefore, it is worth including here some examples of higher education programs developed with the specific intent of achieving a more continuous birth through age 8 orientation (see Box 9-1). These examples are not derived from a comprehensive research effort, nor do they reflect any conclusions the committee drew about best practices or exemplars. They are provided to illustrate some of the approaches that are being used with the aim of improving the quality and consistency of higher education programs for care and education professionals.

Governance and Oversight of Institutions of Higher Education

The governance and oversight of institutions of higher education play a key role in shaping programs for care and education professionals, with implications for program quality, efforts to improve or update program content, and policy development. State agencies, state licensure for teachers, funding sources for institutions of higher education, and accreditation standards are four elements that influence the content and quality of educator preparation programs.

State agencies are responsible for administering and overseeing higher education programs, and they create policies on teacher education and certification, funding, and program approval (Perry, 2011). Many states work toward connecting their policies on teacher certification and licensure with standards set by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) and other organizations (Perry, 2011; Pianta et al., 2010) and establish criteria for specific program requirements, includ-

BOX 9-1

Examples of Higher Education Programs with a Birth Through Age 8 Orientation

New Mexico State University Early Childhood Education Program

The Early Childhood Education program at New Mexico State University (NMSU) is a 2- or 4-year program that grants an associate’s or bachelor’s degree in early childhood education to prospective educators who successfully meet all the program requirements. These requirements include coursework and practicum experience in such areas as family engagement, intersectoral collaboration, and diversity.

Prospective educators at NMSU must complete a field placement requirement. They have the option of completing their practicum at Myrna’s Children Village Laboratory School, which, as part of NMSU, provides services to children, ages 6 weeks to 5 years, of students, faculty, staff, and community members. The program also has field placements in local public elementary schools so that students can experience working with children through third grade.

Courses cover family and community engagement, through which the role of the educator in establishing and maintaining relationships with families is emphasized. Advanced courses also are available, focused on the diversity of families and the influence of culture, socioeconomic status, and language on the development of children and families. Coursework touches as well on working with children and families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and with children with developmental delays or disabilities.

Prospective educators must also acquire the skills to access community resources that have positive impacts on families and children’s development. These include health, mental health, and adult education services.

University of Oklahoma–Tulsa Early Childhood Education Bachelor’s Completion Program

The University of Oklahoma–Tulsa Early Childhood Education program is a five-semester program that has an articulation agreement with the 2-year associate’s program at Tulsa Community College. Successful candidates earn a bachelor of science degree in education upon completion of the program.

Coursework has a child-development focus and includes classwork on infanttoddler development, early childhood development, and language and literacy development for children from birth through third grade. Prospective educators also must complete a field experience requirement with the following age groups: infants/toddlers, preschool-aged children, and primary grade-level children (kindergarten through third grade).

Family engagement is emphasized in both the coursework and practicum requirements. In the infant/toddler course, family engagement is discussed particularly in terms of collaborating with families, maintaining cultural continuity, and

understanding cultural contexts children experience outside the classroom. Prospective educators must work with one child and conduct home visits during the semester as a requirement for the Family and Community Connections course. In addition, they must observe conferences between educators and families.

In an effort to establish connections with practitioners in other sectors, candidates are required to interview early intervention specialists from such programs as Oklahoma Parents as Teachers, Family and Children’s Services, and Sooner Start. They also may collaborate with pediatricians and community activities for their service learning project.

University of Pittsburgh CASE (Combined Accelerated Studies in Education) Program

The CASE program at the University of Pittsburgh is a 5-year program that offers both undergraduate and graduate coursework. Students in the early childhood education program begin their coursework in the Applied Developmental Psychology department. Upon graduation, they receive a bachelor of science degree in applied developmental psychology and a master of education degree in early childhood education.

The required coursework for this program emphasizes child development. It includes a course on development from conception through early childhood and the psychology of learning and development for education, among others. Several courses focus on diversity, including working with dual language learners and understanding race and racism in education. Prospective educators also are required to have knowledge of diverse learners as a field experience competency.

To meet the field experience requirements, candidates must complete passive observations in early childhood classrooms during their sophomore and junior years. During their senior year, they must complete 200-hour field experiences in prekindergarten classrooms and in early intervention or life skills settings. At the graduate level, students are required to serve as full-time student teachers in a primary grade-level classroom and in a special education classroom. Each student teaching experience lasts 14 weeks.

Family engagement is a component of both coursework and training at the University of Pittsburgh. It is discussed extensively in the Child Development course, the Developmental Curriculum course, a number of methods courses, a course on working with dual language learners, and a special education course called Partnership with Families. In practice, prospective educators apply their knowledge of family engagement by volunteering through the Child Development Association student group and other work within the community.

SOURCES: Personal communication, A. Arlotta-Guerrero, University of Pittsburgh, 2014; personal communication, E. Cahill, New Mexico State University, 2014; personal communication, D. M. Horm, University of Oklahoma–Tulsa, 2014; New Mexico State University, 2014; University of Oklahoma, n.d.; University of Pittsburgh School of Education, 2015.

ing recruitment and admission of students, field experience, training, and coursework hours and content (Perry, 2011). NCATE has recommended that states establish policies on incorporating the science of child development into teacher preparation programs, as teacher evaluation systems are moving toward recognizing a teacher’s knowledge of child development and how it is applied in the classroom (Pianta et al., 2010). States also are strengthening policies on teacher effectiveness, having identified teacher assessments as an opportunity to raise standards for teacher preparation programs (NCTQ, 2012).

Teacher licensure and certification (discussed in more detail in Chapter 10) also affect the content and emphasis of higher education programs designed to prepare students to practice. Licenses often cover a broad range of grades, such as prekindergarten to grade 3, kindergarten to grade 5, and kindergarten to grade 12. The overlapping structure of these licenses can lead to overlapping preparation programs that can limit opportunities for learning at either end of the grade spectrum. Additionally, many states do not require that educators of children in kindergarten have any preparation in early childhood development (Bornfreund, 2011). The National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC’s) report on early childhood teacher certification raises the concern that preparation programs for prekindergarten to grade 6 focus on teaching methods suited to older children, and that those graduating from such programs may not have the skills necessary for teaching children in kindergarten classrooms (NAEYC, n.d.). Furthermore, states require exams (Praxis) that measure the knowledge and teaching abilities of prospective educators as a condition for obtaining a teaching license. According to the New America Foundation, however, these tests are not an effective tool for evaluating whether one is an effective teacher as the minimum passing scores “can be so low that they are meaningless” (Bornfreund, 2011).

Sources of funding that are subject to conditions or requirements (such as state funds, grants, scholarships, and financial aid) also can influence the quality and content of educator preparation programs. For example, the Teacher Quality Partnership grant program under Title II of the Higher Education Act is intended to increase student achievement in high-need schools by improving the quality of current and prospective educators. This program holds institutions of higher education accountable for preparing qualified and effective teachers (Cohen-Vogel, 2005; U.S. Department of Education, 1998). Funds from this grant can be used for prebaccalaureate programs that prepare prospective educators, as well as for teacher residency and leadership programs. Specifically, funds can be used to evaluate and improve curriculum, develop field experience criteria, and create induction programs for new teachers (U.S. Department of Education, 1998). Additionally, the T.E.A.C.H. grant is available to prospective teachers entering

teacher preparation programs who agree to teach in a high-need or low-resourced school upon completing their program. Under this agreement, students receive up to $4,000 per year to cover tuition costs. The preparation programs are required to produce highly qualified teachers with the competencies needed to work in low-resourced settings (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.).

Voluntary accreditation standards are another mechanism for influencing higher education programs for care and education professionals. Accrediting agencies are private associations that document whether educational institutions and programs meet a certain level of quality. Although educational institutions are not accredited through the U.S. Department of Education, the government provides the public with a list of accrediting agencies that are recognized for quality based on specified standards (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). The Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) also recognizes accrediting agencies based on its own standards (CHEA, 2010). As of 2007, the U.S. Department of Education recognized 58 accreditors, and CHEA recognized 60 accreditors. At this time, more than 7,000 institutions and fewer than 20,000 programs had been accredited (CHEA, 2008). According to CHEA, accreditation is important for several reasons. First, educational institutions and programs must meet the expectations of the accrediting agencies, which promotes quality. Additionally, students attending accredited institutions and programs have greater access to financial aid, tuition assistance, federal grants, and other funds, and they can more easily transfer credits to other institutions (CHEA, 2015).

Examples of accreditation standards that apply to institutions of higher education with programs for care and education professionals working with children from birth through age 8 include the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) (2013) Interim Standards and the NAEYC Early Childhood Associate Degree Accreditation (ECADA) standards (NAEYC, 2011a). These standards emphasize several themes that influence educator preparation programs, including program content and faculty requirements.

Both ECADA and CAEP emphasize program resources and content in their standards for educator preparation programs. ECADA notes that programs should arrange courses in a logical developmental sequence, and should offer a combination of coursework and practicum requirements relevant to the course content. The required field experiences should allow candidates to apply their coursework knowledge in practice while reflecting the standards of the NAEYC. During the field experiences, faculty should be available to work with the candidates to evaluate and reflect on their experiences. Similarly, the CAEP interim standards require candidates to demonstrate knowledge and skills for working effectively with students in

the classroom, as well as their positive effect on student learning in prekindergarten through grade 12. Prospective educators also must foster the development of all students, assess student learning, and communicate with families. The educator preparation provider must ensure that candidates can demonstrate their skills and knowledge through assessments, and establish program policies and practices that support prospective educators.

High-quality and effective faculty are essential to educator preparation programs, as identified in five of the ECADA standards. Faculty must teach strategies that foster candidates’ learning and application of knowledge, and their coursework must derive from current research. Both the CAEP and ECADA standards identify requirements for quality and effective faculty, including the ability to demonstrate knowledge needed for academic and clinical training in the area in which they are teaching, as well as experience and a degree in early childhood education. Faculty also must be part of the system that supports and advises candidates, along with others who provide career counseling and financial aid information and advisors who ensure that candidates are on the track to complete their program. Additionally, professional learning opportunities for faculty need to be available to keep them engaged in the field and aware of current research and practices.

The ECADA standards focus on many areas related to a preparation program’s mission and overarching goals. To meet the ECADA standards, preparation programs must create a conceptual framework that is connected to the program’s mission, encompasses collaboration with stakeholders, and sets goals and objectives for the program. The framework also should include methods for supporting and preparing prospective educators to teach in diverse, equitable, and inclusive settings. These standards help educator preparation programs align required coursework and field placements with their mission and achieve integration within their communities. Additionally, the ECADA standards reinforce the impact of faculty throughout the preparation program, particularly in the areas of advising and supporting students and fulfilling their responsibilities in the classroom, within the institution, and in the community—an area that is explored less in the CAEP standards.

Conclusion About Accreditation for Higher Education Programs

Carefully considered voluntary standards for quality have been developed for programs offering degrees and certifications for educators of children from birth through age 8, yet these standards have been not been translated consistently into the preparation students receive in higher education programs. Standards, incentives, and resources for accrediting institutions of higher education need to be strengthened,

and regulatory systems need to be aligned with these standards so the standards will be adopted and implemented more consistently and rigorously.

PROFESSIONAL LEARNING DURING ONGOING PRACTICE

This section covers those activities that provide professional learning during ongoing practice, also commonly known as “professional development” or “in-service training.” It is worth noting that some of these learning activities also occur during degree- or certificate-granting programs. Conversely, it is worth noting as well that for many practitioners who do not participate in formal preparation programs, such as those in early childhood settings, these activities during ongoing professional practice often overlap as default preparation for practice.

Professional learning during ongoing practice may include such activities as workshops/trainings/courses, coaching and mentoring, reflective practice, learning networks, and communities of practice. These activities can be delivered through a variety of mechanisms—as part of regular practice, as a training activity embedded in the workplace setting, as an offsite activity in a higher education or other setting (such as nonmetric courses or continuing education units), or through technology-based delivery methods. These activities can be part of a sequenced series of activities or ad hoc activities for specific one-time purposes.

Professional learning during ongoing professional practice can have many purposes, including supporting core competencies; introducing skills, concepts, and instructional strategies that were not mastered or introduced in educator preparation programs; and training educators in new science related to child development and early learning and new instructional tools and strategies. All professional learning has the shared purpose of improving or sustaining the quality of professional practice (Howes et al., 2012), and ultimately improving child outcomes (Blank and de las Alas, 2009; Yoon et al., 2007). The effectiveness of professional learning can therefore be viewed in terms of how well it achieves those two aims.

Professional learning during ongoing practice also is one avenue for promoting more consistent and continuous high-quality learning experiences for children if it is provided with intentional consistency and collaboration among professional learning systems across settings and professional roles. Content and curriculum materials that are developed consistently around the science of child development as well as early learning and professional learning activities that are interconnected provide shared language and goals for educators that facilitate working with each other and other groups, as well as peer communication and collaboration (Brendefur et al., 2013; Bryk et al., 2010; Garet et al., 2001).

The subsections that follow offer an overview of access to and expectations for ongoing professional learning for different professional roles and practice settings, an overview of general standards for professional learning, and then more in-depth discussion of the major types of professional learning and principles for quality that apply to each.

Access to and Expectations for Professional Learning During Ongoing Practice

Expectations and resources for professional learning during ongoing practice vary by professional role and practice setting (see Table 9-4). Educators in elementary school systems typically have requirements for and access to professional learning activities. For educators in other settings and systems, expectations and resources vary by program type and funding stream. Many states have no well-defined, comprehensive system to ensure ongoing professional learning, nor do they have agreed-upon standards or approval systems to ensure the quality of those who provide professional learning activities. Educators in better-funded, school-sponsored public prekindergarten and Head Start programs are more likely to participate in learning opportunities that occur during their paid working hours than are their counterparts in privately operated and funded nonprofit or for-profit centers and programs. These latter educators are more often expected to complete professional learning activities during unpaid evening or weekend hours (Whitebook, 2014).

Perspectives from the Field

Family childcare educators face significant barriers in accessing trainings and workshops and other professional learning supports even when they are made available. These educators often work long hours, usually by themselves, and do not have someone to substitute for them. On top of that, family childcare educators are often owners of their own business, playing the dual-function of administrator and practitioner, leaving little time and space for professional learning.

————————

See Appendix C for additional highlights from interviews.

TABLE 9-4 Overview of Differences in Infrastructure, Requirements, Expectations, and Common Practices for Ongoing Professional Learning

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | ||

|

Induction programs that support teachers in the first years on the job, as well as systems of ongoing professional development throughout their careers, are widespread, and public funding is routinely earmarked for them. School districts, unions, institutions of higher education, and other organizations provide professional development (Whitebook et al., 2009).

|

“Professional development” is a catchall phrase that covers nearly the entire spectrum of training and education available in the field—from introductory training, to informal workshops, to continuing education courses for credit, to college-level work for credit or a degree (Whitebook et al., 2009). Induction and mentoring programs are not routinely available, and many settings do not have a continuing education requirement for teachers (Whitebook et al., 2009). Approximately 30 states have developed training and trainer approval systems to reach all practitioners who work in licensed facilities (Kipnis et al., 2013). |

||

| State-Funded Prekindergarten | Head Start | All Other Early Childhood Center-Based Programs | |

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

Existing Standards for Professional Learning Supports

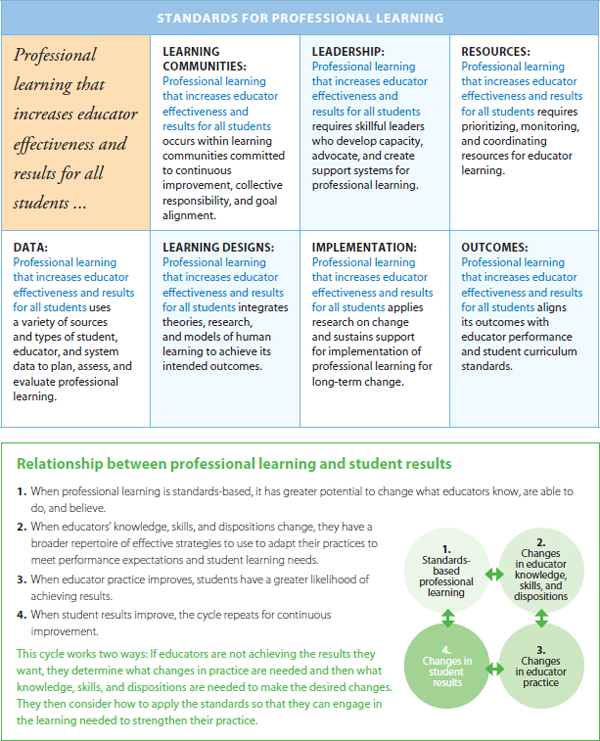

Learning Forward (2014b) has established a set of standards for professional learning, shown in Figure 9-1. It also has suggested several prerequisites for effective, professional learning. One is that the foundation of effective professional learning is participating educators who are committed to engaging in continuous improvement that will foster knowledge and skills to meet the learning needs of all students. Without such continuous learning, knowledge, skills, and practices degrade over time and educators become less adaptable, self-confident, and effective in their work. Part of this commitment is being receptive to professional learning experiences, which is enhanced when the systems providing the professional learning ensure that it is relevant and useful. Another prerequisite is that professional learning needs meet the individual needs of educators, because all learners learn at different rates and in different ways. Different educators may benefit from different types of learning experiences, and may need more or less support in translating new knowledge and skills into practice. Finally, professional learning should have the potential to foster collaborative learning among the participating educators, who may come from different settings or teaching environments and may have disparate levels of experience (Learning Forward, 2014b).

Professional Learning for Instructional Strategies and Tools

Research indicates that effective in-service professional learning is ongoing, intentional, reflective, goal-oriented, based on specific curricula and materials, focused on content knowledge and children’s thinking, and situated in the classroom (Bodilly, 1998; Borman et al., 2003; Bryk et al., 2010; Cohen, 1996; Elmore, 1996; Guskey, 2000; Hall and Hord, 2001; Kaser et al., 1999; Klingner et al., 2003; Pellegrino, 2007; Schoen et al., 2003; Showers et al., 1987; Sowder, 2007; Zaslow et al., 2010). These studies also illustrate the need for professional learning activities to focus on content, including accurate and adequate subject-matter knowledge. Professional learning with the goal of preparing educators to teach subject-matter material is more effective if it is grounded in specific curricula and develops teachers’ knowledge and belief that the curriculum they are learning to use is appropriate, and its goals are valued and attainable. Ideally, the curricula used are research-based materials specifically designed to be educative (Drake et al., 2014). In addition, such training works best when it promotes risk taking, sharing, and learning from and with peers and when it situates work in the classroom. This allows for formative evaluation of fidelity of implementation, with feedback and support from coaches in real time. The

FIGURE 9-1 Standards for professional learning.

SOURCE: Excerpt from Standards for Professional Learning: Quick Reference Guide (Learning Forward, 2014b, p. 2). Used with permission of Learning Forward, www.learningforward.org. All rights reserved.

notion that professional learning should be situated in the classroom does not imply that all training occurs in classroom settings. However, offsite intensive training should remain focused on and connected to classroom practice and be complemented by classroom-based enactment (Bodilly, 1998; Borman et al., 2003; Bryk et al., 2010; Carlisle and Berebitsky, 2010; Clarke, 1994; Cohen, 1996; Elmore, 1996; Garet et al., 2001; Guskey, 2000; Hall and Hord, 2001; Kaser et al., 1999; Klingner et al., 2003; Pellegrino, 2007; Schoen et al., 2003; Showers et al., 1987; Sowder, 2007; Zaslow et al., 2010).

Research findings also have implications for the nature and structure of professional development. Combinations of layers of professional development that include workshops, coaching, and professional development communities can improve teachers’ understanding and use of more effective instructional practices, which in turn result in greater learning for children in their care (Biancarosa et al., 2010; Buysse et al., 2010; Carlisle et al., 2011).

Research suggests that effective professional learning for instructional practices has several key features:

- Develops knowledge of the specific content to be taught, including deep conceptual knowledge of the subject and its processes (Blömeke et al., 2011; Brendefur et al., 2013; Garet et al., 2001).

- Gives corresponding attention to specific pedagogical content knowledge, including all three aspects of learning trajectories: the goal, the developmental progression of levels of thinking, and the instructional activities corresponding to each level—and especially their connections. This feature of professional learning also helps build a common language for educators in working with each other and other groups (Brendefur et al., 2013; Bryk et al., 2010).

- Includes active learning involving the details of setting up, conducting, and formatively evaluating subject-specific experiences and activities for children, including a focus on reviewing student work and small-group instructional activities (Brendefur et al., 2013; Garet et al., 2001).

- Focuses on common actions and problems of practice, which, to the extent possible, should be situated in the classroom.

- Grounds experiences in particular curriculum materials and allows educators to learn and reflect on that curriculum, implement it, and discuss their implementation.

- Includes in-classroom coaching. The knowledge and skill of coaches are of critical importance. Coaches also must have knowledge of the content, general pedagogical knowledge, and pedagogical con-

-

tent knowledge, as well as knowledge of and competencies in effective coaching.

- Employs peer study groups or networks for collective participation by educators who work together (Garet et al., 2001).

- Incorporates sustained and intensive professional learning experiences and networks rather than stand-alone professional learning activities (Garet et al., 2001).

- Ensures that all professional learning activities (e.g., trainings, adoption of new curricula, implementation of new standards) are interconnected and consistent in content and approach (Brendefur et al., 2013; Garet et al., 2001). This consistency also involves a shared language and goal structure that promote peer communication and collaboration.

- Ties professional learning to the science of adult learning. There is now increasing recognition of the importance of multiple, comprehensive domains of knowledge and learning for adults (NRC, 2012).

- Addresses equity and diversity concerns in access to and participation in professional learning.

- Addresses economic, institutional, and regulatory barriers to implementing professional learning.

The following subsections provide examples of the features of high-quality professional learning applied for different subject-matter content, namely literacy and mathematics, as well as for the use of technology for instruction. Although this section focuses on instructional strategies and tools, it is important to note that care and education professionals also need to learn both to develop high-quality environments and to have high-quality interactions with children within those environments. For example, research suggests that in addition to stronger gains in language, reading, and math skills due to the quality of instruction in higher-quality preschool classrooms, the quality of teacher–child interactions was linked to higher social competence and lower levels of behavior problems (Burchinal et al., 2010). This finding reaffirms the importance of supporting early childhood professionals in both instructional strategies and in establishing positive educator–child relationships with the aim of helping students make greater academic and social gains. As discussed in Chapter 4, positive educator–child interactions have a strong influence on multiple outcomes of development and early learning.

Literacy