WORKSHOP IN BRIEF |

Advising the nation • Improving health |

Cross-Sector Responses to Obesity: Models for Change—Workshop in Brief

On September 30, 2014, the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions held a 1-day workshop titled “Cross-Sector Work on Obesity Prevention, Treatment, and Weight Maintenance: Models for Change.” The workshop was designed to explore models of cross-sector work that may reduce the prevalence and consequences of obesity, discuss lessons learned from case studies of cross-sector initiatives, and spur future cross-sector collaboration.

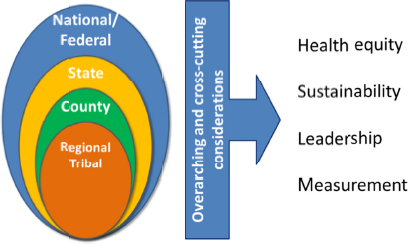

The first half of the workshop examined four considerations important to cross-sector work: health equity, sustainability, leadership, and measurement. The second half of the workshop examined five case studies that represent cross-sector collaboratives at different levels of organization, from the tribal and regional to the county, state, and national levels (see Figure 1).

This brief summary of the workshop highlights the salient points that emerged from the presentations and discussions at the workshop. These points represent the viewpoints of speakers; statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). They should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus. A full summary of the workshop will be available in early 2015.

Cross-Sector Collaboration

The 2012 IOM report Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention laid out an inspirational vision of healthy children, healthy families, and healthy communities in which all people develop the competencies required to interact successfully with their environments, said Nicolas Pronk, vice president for health management and chief science officer for HealthPartners, Inc., in his introductory remarks at the workshop. Achieving this vision will require large-scale transformative approaches focused on multilevel and interconnected environmental and policy changes, Pronk continued. In particular, it will require changes in many of the environments in which people interact, including schools, the messages that surround us about nutrition and physical activity, the physical activity environment, the

SOURCE: As presented by Nicolas Pronk on September 30, 2014.

food and beverage industry, and the health care and work environments. Furthermore, because these environments are affected by activities that occur simultaneously across multiple sectors, an explicit focus on cross-sector work is essential.

Cross-sector work may go beyond normal partnering or day-to-day transactional behaviors and connecting with institutions, disciplines, and bodies of knowledge in new ways. This requires recognizing shared goals, ownership, decision making, burdens, and rewards. “This joining together will allow for synergies that move us beyond what any person or group can accomplish alone,” said Pronk.

In some cases, cross-sector work involves alliances of seemingly disparate nonprofit or government organizations that share the common ground of obesity prevention. In other cases, cross-sector work is more informal but still allows the leveraging of disparate strengths to achieve mutual benefits. Whatever the arrangement, Pronk observed, “shared ownership, transparency in decision making, mutual respect and trust, and an authenticity in purpose and process are important attributes of such approaches.”

Health Equity

Today, people who live in communities of color or in communities with low incomes are more likely to have a higher prevalence of obesity than those who live in mostly white or more affluent communities, said Mildred Thompson, director of the Center for Health Equity and Place at PolicyLink. Achieving greater equity requires concentrating resources in the places that have the poorest health outcomes, or in this case, the highest rates of obesity. It also requires changing multiple aspects of the environment, not just trying to change individuals. For example, jobs in the current labor market tend to require higher levels of education than many marginalized communities may possess. This new labor market then leaves some communities with low rates of employment, impacting their economic security, which is later reflected in poorer health outcomes. This link between educational achievement and health thus illustrates the importance of cross-sector approaches and engagement of the education sector to improve health.

According to research done by PolicyLink, organizations need to adopt an explicit focus on health equity when drafting policies, implementing solutions, or developing research agendas and policy options to achieve progress. This institutionalization of health equity extends throughout the areas of data collection and analysis and strategy development; for example, organizations need to ask explicitly how their actions help achieve greater racial and economic equity, Thompson said. Organizations also need to engage communities in substantive ways, she said, preferably by placing people from the community in decision-making roles. However, this requires developing the capacity of communities and the skills of individuals to participate in the work of an organization or cross-sector collaborative.

Sustainability

Sustainable obesity solutions are important if they are to have long-term impact, suggested Donald Hinkle-Brown, chief executive officer of The Reinvestment Fund (TRF). Cross-sector work can create innovative and multifaceted ways of funding and supporting initiatives while building community capital. In this way, such work builds sustainability by connecting projects, people, and resources.

The investments being made by community development financial institutions (CDFIs) are an example of such cross-sector work, said Hinkle-Brown. (The TRF is a Philadelphia-based CDFI). These organizations connect communities disconnected from traditional financial networks to funding opportunities. They bring together people, financing, capacity building, and metrics to promote socially responsible development that intentionally sets desired outcome goals and holds stakeholders accountable for the outcomes.

In recent years, the community development and public health fields have begun to find common ground as understanding grows of those ingredients needed to create a healthy community: housing, human services, transportation, food systems, and environmental sustainability. Hinkle-Brown noted that as these sectors converge, the community development field has become less focused on deals, transactions, and volume and more focused

on long-term outcomes or impacts. He observed that the public health field has become less reactionary to poor health outcomes and more focused on preventing them by addressing the social determinants of health. As the two meet, community development partners are able to teach those in the public health field how to build more sustainable initiatives and consider how to break down societal challenges such as obesity into granular solutions and transactions.

For example, Hinkle-Brown described how TRF helped finance a development in an area of limited food access that includes both a grocery store and a federally qualified health center (FQHC). The grocery store presents the FQHC with the opportunity to meet those people who would not ordinarily walk into a clinic, while the FQHC provides the grocery store with new shoppers. Further, the two organizations are now sharing objectives around diabetes education and coordination. TRF has found that for CDFIs, financing a grocery store in a food desert can be a profitable investment, while for grocers this can be a sustainable business platform, and that both can have long-term, sustainable impacts on a community’s health outcomes.

Leadership

Leadership is the “secret sauce” of cross-sector work that “can make or break collaborative efforts,” said Debra Oto-Kent, executive director of the Health Education Council of Sacramento, CA. Oto-Kent identified key lessons for leaders in championing cross-sector collaborations. Important lessons include an investment in understanding the varied terminology used by partners in disparate sectors; taking the time to understand the diverse views, goals, relationships, and relevant intersections of the involved sectors coming together; identifying and being open to opportunities as they happen; and building relationships, history, and trust over time.

Leaders can have a variety of attributes that contribute to the success of collaborative efforts, Oto-Kent observed. They are relationship builders who respect others’ expertise and recognize that champions come in many forms and believe in shared leadership and ownership. Leaders build understanding of why stakeholders need to feel represented or be at the table to earn trust of the partners. They understand the process of collaboration, set milestones, and seek the sweet spot between listening and doing. Leaders ensure that the structure of a collaboration is flexible while moving forward strategically, and they recognize that conflict is common in partnerships and use relationships and strategies to equalize power and seek solutions.

Oto-Kent also emphasized the importance of resident leadership. Local leaders have a different ability to change neighborhoods than do external organizations.

Measurement

Communities across the country are currently undergoing transformations and improving access to and opportunities for healthy food and physical activity. However, it is not fully understood how these changes are impacting people’s behaviors and affecting population health. To understand how likely communities are to see improvements in population health if they stay the course, evaluations need to measure the changes produced by an initiative by carefully looking at short-term, intermediate, and long-term outcomes, said Pamela Schwartz, director of program evaluation for Kaiser Permanente. While such measurements can indicate whether an intervention is capable of changing the health of a population over time, knowing the right intermediate outcomes to measure, and knowing where those outcomes may lead in the long term, can be a major challenge for communities. Schwartz noted the importance of engaging communities in designing and deploying evaluation strategies to understand the full impact of initiatives.

Schwartz and her colleagues have approached evaluation through what they call “dose,” which she defined as the product of reach, or the number of lives affected by an intervention, and the strength of that intervention (see Figure 2). “If we don’t have dose, we’re unlikely to see impact at the population level,” she said. The effects of an intervention can be estimated through a combination of effect sizes derived from the scientific literature, evaluations of individual strategies, and dose estimates based on reach and strength. Surveys of the target population

SOURCE: As presented by Pamela Schwartz on September 30, 2014.

then can be compared with control populations to identify behavior changes. “We’re looking for associations between the estimated and measured impact. If we see those, we feel more confident that the changes we’re seeing in population health can be attributed to the work we’re doing.” Such associations in turn provide feedback for program administrators and policy makers to make adjustments in interventions.

Evaluations are more complicated for cross-sector collaborations, where multiple strategies are occurring simultaneously. Schwartz noted that schools are ripe for identifying strong interventions, measuring outcomes, and implementing this type of cross-sector approach to health improvement. For cross-sector work in communities, measurement is inherently more difficult—communities are hard to reach, saturated with many efforts that are not always aligned, and progress is hard to document. Applying dose methods may help to prioritize cross-sector interventions and understand which models work best.

Case Studies

The second half of the workshop examined five case studies of successful cross-sector initiatives to fight obesity. Speakers described the barriers, challenges, and lessons learned from their initiatives in the context of the four considerations of health equity, sustainability, leadership, and measurement.

The National Prevention Council

Mandated by the Affordable Care Act of 2010, the National Prevention Council (NPC) is coordinating prevention and wellness activities across and within 20 federal agencies that employ more than 4 million Americans, as described by Acting Surgeon General Rear Admiral Boris D. Lushniak. In 2011, the Council released the National Prevention Strategy, which lays out four strategic directions: healthy and safe community environments, clinical and community preventive services, empowered people, and the elimination of health disparities. Of seven priority areas specified by the Council, two—healthy eating and active living—are directly related to obesity solutions.

The National Prevention Strategy has catalyzed a wide range of activities and has provided a model for organizations inside and outside government through its 2012 Action Plan—a follow-on to the Strategy. The NPC’s member agencies have introduced the concept of prevention into the lives of federal employees, made efforts to create tobacco-free workplaces, and increased access to healthy foods. For instance, the Rocky Mountain office of the General Services Administration, as described by Regional Administrator Susan Damour, has brought in farmers’ markets and supported bike share programs and walking paths around federal buildings in that region. Lushniak described how the very process of cross-sector collaboration on the NPC has engendered change: Some agencies that did not initially see prevention, wellness, and health promotion as part of their mandates underwent a shift in attitude after working on the strategy.

Damour and Jeff Levi, chairperson of the prevention advisory group for the NPC and executive director of the Trust for America’s Health, described major challenges of implementing the action plan. These include a

shortage of funding, maintaining momentum over time as administrations and political appointees change, and getting (and making it easier for) agencies to work together across jurisdictions instead of only within their agency. At the same time, obesity has become a major driver of health care costs, which creates an incentive to implement workable solutions, concluded Levi.

A Statewide Strategy to Battle Child Obesity in Delaware

Nemours, a pediatric health system, has devised a cross-sector, community-based approach to preventing childhood health problems, including obesity, across the state of Delaware. Nemours, as described by Debbie Chang, enterprise vice president of policy and prevention at Nemours, has served as an “integrator,” pulling together all the systems involved in caring for children, including schools, childcare programs, primary care providers, and the community. The goal has been to connect clinical care and population health into an integrated community health model.

Child care and schools are examples of partners in this statewide approach. Helen Riley, executive director of St. Michael’s School, described the significant importance and positive impact that early childhood care has made in addressing all aspects of children’s well-being with the support of Nemours, the community, and other partners. Riley stressed the importance of integrating the family and the caregiver in sustaining the successes of the work with young children. Additionally, Mary Beth French, a physical educator who is content chair for physical education and health teachers in the Christina School District, described one program implemented in their schools that was designed to help public elementary schools incorporate 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity into the school week for every student. French identified elements of their work that were key to their success, including training, providing solutions to barriers in implementing the program, and providing opportunities to share and connect with others.

One key lesson of the prevention work in Delaware, according to Mary Kate Mouser, operational vice president of Nemours Health and Prevention Services, has been to be flexible and let community partners lead the way. Another is that evaluation of outcomes is essential to guide future activities for the individual partners and the collective impact of the cross-sector work. Finally, sustainability is dependent on opportunistic policy formulation, continued funding streams, developing shared goals across the partners, and effective leaders across levels and sectors.

Chang reported that Nemours is now working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on spreading its collaborative approach to nine other states across the United States, as rates of overweight and obesity among Delaware’s children have leveled off and the proportion of children who get at least an hour of physical activity per day has increased.

Cook County Place Matters

Jim Bloyd, regional health officer at the Cook County Department of Health, opened by describing Cook County Place Matters (CCPM) as one of 19 regional projects under a national initiative of the National Collaborative for Health Equity. It brings together labor organizations, the education system, governmental public health departments, and community advocates to work toward eliminating structural racism so that all residents of Cook County, Illinois (which includes the city of Chicago) have the opportunity to live healthy lives. This program operates from the view that the obesity epidemic is driven by poverty, structural racism, social class, poor education systems, and poor access to healthy foods—barriers that disproportionately affect people of color.

Bloyd noted that during the twentieth century, federal and local housing policies created Cook County neighborhoods deeply segregated by race. Bloyd described an example of structural racism as historical, cultural, institutional, and interpersonal dynamics that routinely advantage whites and harm people of color are brought together in these housing policies, which normalize and legitimatize racism. Today, neighborhood segregation has a profound impact on education, health, and obesity: for communities of color, neighborhood public schools receive little funding, leading to low-quality education and low-quality school foods. Bloyd described that in south suburban Cook County, child poverty rates are higher, life expectancy is 14 years shorter, and black childrens’ diets contain fewer fruits and vegetables than children living in wealthier north suburban Cook County. Tackling these difficult issues will take collaborative partnerships with leaders working in schools, health, and policy.

Organizing grassroots “people power” for social justice is one way to enact public health policies that will reduce those barriers, the project believes. For example, CCPM’s community partners include a labor organization that fights inequities in the restaurant industry, including low wages, rampant labor violations, and racial discrimination. Felipe Tendick-Matesanz, National High Roads Program director at Restaurant Opportunities Center United, noted that nearly 90 percent of restaurant workers do not receive paid sick days, and lower wage positions are predominantly filled by women and people of color.

CCPM has recommended that the voices of neighborhood residents be reflected in solutions to hunger and poor nutrition and that persistent poverty be addressed by engaging multiple sectors. Bonnie Rateree, a community advocate for CCPM, noted that people in communities are the experts on their own lives and on what they want and need. Therefore, engaging them in the design of solutions and policies can have a major effect on the nutrition, food, education, labor, and social systems that reflect and perpetuate inequality.

PowerUp

Sue Hedlund, retired deputy director of the Washington County Department of Public Health and Environment, described PowerUp as a long-term (10-year) regional children’s health initiative, anchored by two lead health care institutions, that targets two counties in the St. Croix Valley region straddling Minnesota and Wisconsin. Launched in 2013 by HealthPartners, Inc., and Lakeview Health, the endeavor harnesses the resources and social capital of 13 different sectors and 130 community advisors representing health care, schools, early childhood programs, parents, business, civic organizations, and faith community groups, among others. PowerUp is based on the idea that multiple levels of intervention are needed for a comprehensive approach against childhood obesity, including community engagement, changes in the environment, programs to change individual behavior, clinical care systems, and relationship building across sectors and levels.

One critical lesson of PowerUp has been that shared leadership with communities is essential for authenticity, momentum, and sustainability. Hedlund noted that the program was not originally an obesity-focused one (its purpose was to advance health more broadly), but community members identified obesity as a principal health concern that they wanted to address. Hedlund also noted that the most important stakeholders in their program are parents and children, who inform the project through shared leadership, decision making, and recognition. The program intentionally uses language that is digestible for all community members, and not specific to the public health or health care sector. The initiative’s on-the-ground progress is happening through partnerships with local health departments, hospital cafeterias, and schools. Marna Canterbury, director of community health at Lakeview Health Foundation, observed that the St. Croix Valley is a rural region, termed an “exercise desert,” and lacks public transportation or easily accessible recreation facilities. The region’s weather also makes outdoor physical activity a challenge. In one collaboration, PowerUp has thus developed partnerships with school districts to open their gymnasiums to the community every week for free, or at low cost, during the winter.

Changing a culture is difficult, and measuring this culture change is especially challenging, noted Donna Zimmerman, senior vice president of Government and Community Relations for HealthPartners, Inc. Zimmerman remarked that PowerUp has used evaluations to measure both their outcomes and the difference the initiative has made over time, including through surveys of parents about children’s eating behaviors. Dedicated staff have been critical in convening and listening to community advisors, facilitating consensus, building community relationships, and providing expertise in evaluation.

The Sault Ste. Marie (MI) Tribe of Chippewa Indians

The Sault Tribe Community Transformation (STCT) initiative has been strategically leveraging community health grants to improve health and reduce disparities among communities of Chippewa Indians living in Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula. Donna Norkoli, project coordinator of the initiative, described how this collaborative and participatory approach has helped engage and bring change across tribal and nontribal sectors to improve the

community. The initiative is overseen by a tribal leadership team of decision makers who are instrumental in bringing policy, systems, and environmental changes to the tribal agencies where they work. Represented sectors include housing, transportation, economic development, enterprise (i.e., casinos), early childhood, and youth activities.

For example, STCT worked with local non-tribal public schools to help them build capacity and infrastructure to form coordinated school health teams and conduct assessments of their environments. Norkoli reported that the Sault Tribe also has provided funding to local government agencies to collaboratively create non-motorized transportation plans that make streets safer and friendlier for walking and biking.

Jeff Holt, a Sault Tribal leader, described one key to sustaining the initiative’s efforts has been integrating tribal members’ voices into municipal decision-making processes. Sault Tribe has worked to create formal agreements with local governments, while tribal members provide input by serving on local municipal committees and advisory boards. Although barriers exist, including lack of resources, time, and public transportation among the various partners, Holt described the importance of building relationships and identifying shared priorities as key aspects of a successful collaboration.

A participatory, respectful, and culturally sensitive approach to data collection has been the key to earning the cooperation of the tribe’s leaders in using and sharing information, stressed Shannon Laing, lead of the evaluation team for the initiative. Since 2008, more than 100 assessment tools for use in different sectors across the service region have been developed as well as a tribal health assessment survey. These data have shown positive increases in measures of the physical, built, and food environments and have been integral to an annual prioritization and action planning process used by local coalitions.

Concluding Remarks

During the final session of the workshop, three members of the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions provided their perspectives on some of the messages that emerged from the presentations and discussions.

- Work on obesity solutions will continue to occur within individual sectors, observed Russell Pate, University of South Carolina, Columbia, vice-chair of the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions. But expanded cross-sector approaches have the potential to deliver both dose and reach, which can in turn better decrease obesity rates.

- Successful models of such approaches exist, as demonstrated by the programs discussed at the workshop. But they need to be sustainable, which requires not just private support but the backing of governmental policy, legislation, and funding, according to Pate.

- Though successful models exist, a unifying and compelling narrative around equity, obesity prevention, or health has not yet been developed, said Marion Standish of the California Endowment. Clarity of goals is critical in scaling up models, enlisting community engagement, and holding programs accountable.

- Successful models need to be disseminated and implemented to communities across the country, Standish added, which requires community capacity and the development of local leaders to implement programs successfully.

- Measures of the return on investments from cross-sector work on obesity, especially within the context of the Affordable Care Act, can generate further support for such efforts, Standish said.

- Openness and optimism are needed to work across sectors successfully, said Maha Tahiri of General Mills, Inc., along with sustained dedication to the work from all partners, a deep knowledge of the communities in which partner organizations are working, and a commitment to keeping “health equity first in mind in everything we design.”

Roundtable on Obesity Solutions

Bill Purcell III (Chair)

Jones Hawkins & Farmer, PLC, Nashville, TN

Russell R. Pate (Vice Chair)

University of South Carolina, Columbia

Mary T. Story (Vice Chair)

Duke University, Durham, NC

Sharon Adams-Taylor

American Associaton of School Administrators, Alexandria, VA

Nelson G. Almeida

Kellogg Company, Battle Creek, MI

Leon Andrews

National League of Cities, Washington, DC

Shavon Arline-Bradley

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Baltimore, MD

CAPT Heidi Michels Blanck

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Don W. Bradley

Duke University, Durham, NC

Cedric X. Bryant

American Council on Exercise, San Diego, CA

Heidi F. Burke

Greater Rochester Health Foundation, Rochester, NY

Debbie I. Chang

Nemours, Newark, DE

Yvonne Cook

Highmark, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA

Edward Cooney

Congressional Hunger Center, Washington, DC

Kitty Hsu Dana

United Way Worldwide, Alexandria, VA

Christina Economos

Tufts University, Boston, MA

Ihuoma Eneli

American Academy for Pediatrics, Columbus, OH

Ginny Ehrlich

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ

David D. Fukuzawa

The Kresge Foundation, Troy, MI

Lisa Gable

Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, Washington, DC

Paul Grimwood

Nestlé USA, Glendale, CA

Scott I. Kahan

STOP Obesity Alliance, Washington, DC

Shiriki Kumanyika

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Catherine Kwik-Uribe

Mars, Inc., Germantown, MD

Theodore Kyle

The Obesity Society, Pittsburgh, PA

Matt Longjohn

YMCA of the USA, Chicago, IL

Lisel Loy

Bipartisan Policy Center, Washington, DC

Mary-Jo Makarchuk

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Toronto, ON

Linda D. Meyers

American Society for Nutrition, Bethesda, MD

H. Melvin Ming

Sesame Workshop, New York, NY

Shellie Pfohl

President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, & Nutrition, Rockville, MD

Barbara Picower

The JPB Foundation, New York, NY

Nicolas P. Pronk

HealthPartners, Inc., Minneapolis, MN

Amelie G. Ramirez

Salud America!, San Antonio, TX

Olivia Roanhorse

Notah Begay III Foundation, Santa Ana Pueblo, NM

Sylvia Rowe

S.R. Strategy, LLC, Washington, DC

Jose (Pepe) M. Saavedra

Nestlé Nutrition, Switzerland

Margie Saidel

Chartwells School Dining Services, Toms River, NJ

James F. Sallis

University of California, San Diego

Eduardo J. Sanchez

American Heart Association, Dallas, TX

Brian Smedley

National Collaboration for Health Equity, Washington, DC

Lawrence Soler

Partnership for a Healthier America, Washington, DC

Loel S. Solomon

Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA

Alison L. Steiber

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Chicago, IL

Maha Tahiri

General Mills, Inc., Minneapolis, MN

Kathleen Tullie

Reebok, International, Canton, MA

Tish Van Dyke

Edelman, Washington, DC

Howell Wechsler

Alliance for a Healthier Generation, New York, NY

James R. Whitehead

American College of Sports Medicine, Indianapolis, IN

DISCLAIMER: This workshop in brief has been prepared by Steve Olson, Leslie Sim, and Sarah Ziegenhorn, rapporteurs, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the authors or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this workshop in brief was reviewed by Don Bradley, Duke University, and David Fukuzawa, Kresge Foundation. Chelsea Frakes, Institute of Medicine, served as review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was partially supported by Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; Alliance for a Healthier Generation; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Sports Medicine; American Council on Exercise; American Heart Association; American Society for Nutrition; Bipartisan Policy Center; Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina; ChildObesity180/Tufts University; Edelman; General Mills, Inc.; Greater Rochester Health Foundation; HealthPartners, Inc.; Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation; Highmark, Inc.; The JPB Foundation; Kaiser Permanente; Kellogg Company; The Kresge Foundation; Mars, Inc.; Nemours Foundation; Nestlé Nutrition; Nestlé USA; The Obesity Society; Partnership for a Healthier America; President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition; Reebok, International; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Salud America!; Sesame Workshop; and YMCA of the USA.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit www.iom.edu/crosssector.

Copyright 2014 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.