2

The Burden of Cognitive Dysfunction in Depression

Highlights

- Cognitive dysfunction in depression occurs as both cognitive biases and deficits (Nierenberg).

- There are impairments in both hot and cold cognitive processes in depression (Sahakian).

- Depression represents a disorder of brain circuits; a better understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of cognitive dysfunction in depression could point the way to improved treatments (several workshop participants).

NOTE: These points were made by the individual speakers identified above; they are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Cognitive dysfunction in depression has been relatively overlooked by clinicians, academic researchers, and industry, said Andrew Nierenberg, who holds the Thomas P. Hackett, M.D., Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital. However, there is now increased recognition that cognitive dysfunction in depression occurs as both cognitive biases, such as distorted information processing and increased attention to negative stimuli, and cognitive deficits, such as impairments in attention, short-term memory, and executive functioning (Murrough et al., 2011). The consequence of these cognitive impairments, said Nierenberg, is that in the presence of emotionally laden negative thoughts, the person with depression lacks the cognitive flexibility to regulate mood. He or she becomes “stuck in a rut” (Holtzheimer and Mayberg, 2011).

COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION: A CORE ELEMENT OF DEPRESSION

Cognitive dysfunction affects both cold (i.e., emotion-independent) and hot (i.e., emotion-laden) cognition, said Barbara Sahakian, professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge and the Medical Research Council/Wellcome Trust Behavioral and Clinical Neuroscience Institute (Roiser and Sahakian, 2013). The sustained attention and planning needed for arranging a meeting or formulating a business plan, for example, requires intact cold cognitive processes; depressed patients show consistent impairments in these domains (Clark et al., 2009). Hot cognition, in contrast, involves thinking patterns that are influenced by emotions, such as the negatively biased responses that are common in depression and decision making when there is a conflict between risk and reward. Indecisiveness, one of the DSM-recognized criteria for depression, represents dysfunction in both cold and hot cognitive processes.

Importantly, cognitive dysfunction impacts both functionality and psychosocial functioning, which contribute to poor outcome and high relapse rates (Bortolato et al., 2014). For example, in a study of 48 patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of MDD, nearly 60 percent remained functionally disabled 6 months after hospitalization despite significant improvement in depressive symptoms (Jaeger et al., 2006). According to Sahakian, persisting deficits in information processing, memory, and verbal fluency predict poor academic, occupational, and daily functioning in MDD and are among the most debilitating problems for patients (Lee et al., 2012). These cognitive deficits result in poor workplace functionality and elevated costs due to absenteeism and reduced productivity. Indeed, the indirect costs related to workplace issues are the major contributor to the economic burden imposed by MDD (Fineberg et al., 2013; Greenberg et al., 2015; Olesen et al., 2012).

Various components of cognition can be measured objectively with multiple neuropsychological tests. Sahakian coinvented the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) (Sahakian and Owen, 1992), which tests multiple aspects of mental functioning using nonverbal approaches. These and other cognitive tests show that patients with depression have moderate deficits in spatial working memory as well as problems in other forms of executive function, attention, and memory. In addition, remitted patients continue to show problems in executive functioning and attention.

NEUROBIOLOGY OF COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT IN DEPRESSION

Depression, like other mental disorders, represents a disorder of brain circuits (Insel et al., 2010), and the suboptimal effectiveness of currently available treatment likely reflects an incomplete understanding of the neurobiology of depression and, in particular, its neurobiological relationship to cognitive dysfunction, according to several workshop participants.

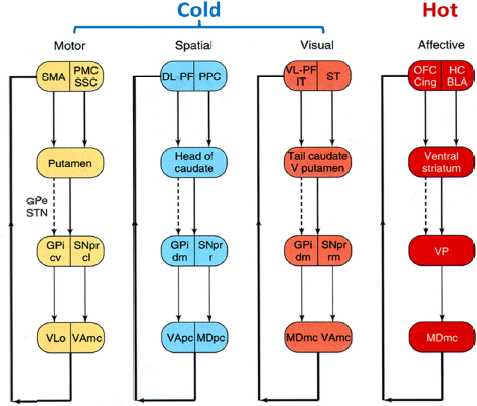

In 1986, Garrett Alexander and colleagues described five parallel and partially segregated loops that link the cortex to the basal ganglia (Alexander et al., 1986; Lawrence et al., 1998). Sahakian said the cold cognitive loop has to do with planning and problem solving, whereas the hot affective loop links emotional brain areas with the orbitofrontal cortex (see Figure 2-1).

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), characteristic patterns of brain activation in depressed patients have been identified. Catherine Harmer, professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Oxford, said depressed patients show increased activation in task-positive networks (networks that are activated in response to attention-demanding tasks) in areas such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which is involved in attention-demanding tasks such as spatial working memory tasks (Fitzgerald et al., 2008; Harvey et al., 2005; Matsuo et al., 2007; Walter et al., 2007), and reduced deactivation in a network called the default-mode network (DMN), which is involved in reflective thinking (Norbury et al., 2014; Rose et al., 2006). According to Harmer, in depressed patients task-positive networks go into overdrive while, at the same time, patients find it difficult to switch off the DMN, which may contribute to rumination. Modulating these circuits are neurotransmitters such as dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin, said Sahakian.

One phenomenon observed in patients with MDD, as well as in those with subclinical depression and even healthy controls with genetic variants linked to an increased risk for depression, is the tendency to have “catastrophic reactions to errors,” said Diego Pizzagalli, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (Elliott et al., 1997; Holmes and Pizzagalli, 2008a; Holmes et al., 2010; Pizzagalli et al., 2006). What this means is that after a mistake is made even on a relatively simple neuropsychological task, performance is significantly impaired, said Pizzagalli.

FIGURE 2-1 Cold and hot cognitive cortico-striatal circuits in the human brain.

NOTE: BLA, basolateral amygdala; Cing, anterior cingulate; cl, caudo-lateral; cv, caudo-ventral; DL-PF, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; dm, dorsomedial; GPe, external segment of globus pallidus; GPi, internal segment of the globus pallidus; HC, hippocampus; IT, inferior temporal cortex; mc, magnocellularis; MD, mediodorsal thalamus; o, pars oralis; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; pc, parvocellularis; PMC, premotor cortex; PPC, posterior parietal cortex; r, rostral; rm, rostromedial; SMA, supplementary motor area; SNpr, substantia nigra, pars reticulata; SSC, somatosensory cortex; ST, superior temporal gyrus; STN, subthalamic nucleus; V putamen, ventral putamen; VA, ventral anterior thalamus; VLo, ventrolateral thalamus; VL-PF, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; VP, ventral pallidum SOURCE: Adapted from Lawrence et al. (1998, fig. 1). Presented by Barbara Sahakian at the IOM Workshop on Enabling Discovery, Development, and Translation of Treatments for Cognitive Dysfunction in Depression, February 24, 2015.

Neurobiologically, this can be explained by a combination of dysfunctions: over-recruitment of regions of the brain necessary for responding quickly and automatically to emotionally salient cues (e.g., the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, or rostral anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]) coupled with an inability to recruit the brain region responsible for regulating emotion (e.g., the left DLPFC) (Holmes and Pizzagalli, 2008b). In addition, there may be increased coupling between the rostral ACC and the amygdala, leading to an inability to cope with the task and excessive rumination, said Pizzagalli (2011).

DEFINING COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT IN DEPRESSION

Given the importance of cognitive impairment in depression, several workshop participants called for an expansion of the diagnostic criteria for MDD in the DSM-5, particularly to include symptoms that capture hot cognition, which is important in depression. Of the nine diagnostic criteria currently listed, only one, “diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness,” clearly represents a cognitive issue (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Several participants noted, however, that research on hot cognition is sparse, and called for additional research to clarify the underlying biology of cognitive impairment in depression, in particular hot cognition.

This page intentionally left blank.