4

Sharing Visions and Working Toward the Future

A vision that inspires people and ennobles a cause can transform dreams into reality. But one needs builders to realize a vision, builders who can develop ideas and movements, who can mobilize the talents and resources required to succeed. When the vision is clear and the impulse to succeed is strong, builders can create structures that endure.

As noted in several sections of this report, many laudable and durable building blocks to help raise the presence of minorities in the health professions are now in place, established over the last decades by government, the academic sector, and a number of foundations. But these worthwhile efforts, often working independently, over a limited period of time, or focused primarily at the later stages of the educational and training pathway, have been insufficient. We have yet to build the infrastructure and momentum to produce and sustain an adequate number of minority professionals among the ranks of America's clinicians, researchers, and teachers. Minorities in the health professions remain significantly underrepresented.

The Institute of Medicine's Committee on Increasing Minority Participation in the Health Professions envisions a health professions workforce for the future that looks more like America. The nation needs a new set of policies, programs, and priorities that can lead to a new approach to training minorities for the health professions, one that both celebrates and reflects America's changing demographic and economic profile.

There is today a bright window of opportunity to revitalize and move forward this nation's stalled commitment to enhancing minority participation in medicine and other health careers. Such optimism derives from several factors. There is new emphasis on investing in the domestic agenda, with a special focus on improving the education and skills of America's future workforce. Reform of the nation's health care system has become a political and economic priority.

The administration's vision for health care reform calls for the "creation of a new health workforce," and enhanced investment in "recruiting and supporting the education of health professionals from population groups underrepresented in the field" (American Health Security Act, 1993).

The current call for systemic change is compelling academic health centers and other institutions involved in education for the health professions to reassess future health workforce needs within a context of universal access and the health care needs of a more diverse society. The problem of dwindling access and declining coverage has brought into sharper relief the special health needs of underserved Americans, of whom a disproportionate number are minorities. Further, there is every indication that any reform strategy will provide incentives for enlarging the ranks of primary caregivers, nurses, and allied health professionals who enter community practice, a focus that represents promising career opportunities for minorities.

To meet the needs for health care, education, and research in an increasingly diverse society, the committee tried to formulate a strategy that would ensure a significant increase and a continuous supply of minority health professionals. The committee believed it critical to recommend greater emphasis on the "throughput"* of the educational process and on programs that will significantly increase the number of minorities prepared academically to pursue careers in medicine and science. Past reliance on stand-alone, rather than integrated, programs has nourished only a few institutions that compete for a small number of talented minority students and faculty. A greater presence of minorities in the health professions in clinical practice and research cannot, however, be reached by the field of medicine alone. Energized, sustained, and concerted strategies must involve the other health professions as well, including dentistry, optometry, pharmacy, podiatric medicine, veterinary medicine, nursing, and the growing field of allied health.

The committee calls for a more systematic, strategic, and sustained effort to ensure the continuous flow of minority students qualified to choose careers in the health professions. Any substantial improvement in minority enrollment in health profession's schools can occur only if the pipeline expands and more minority students gain the opportunity for solid academic preparation in a supportive environment, beginning well before high school. The fundamental cause of underrepresentation of minorities in health professions schools is an inadequate number of academically qualified and near-qualified students interested in health

(Baratz et al., 1985). Many past programs and strategies have relied too heavily on supplementary enrichment and recruitment programs for advanced premedical and postgraduate students. They have failed to address the root cause—the need to develop the applicant pool at earlier stages of the educational process.

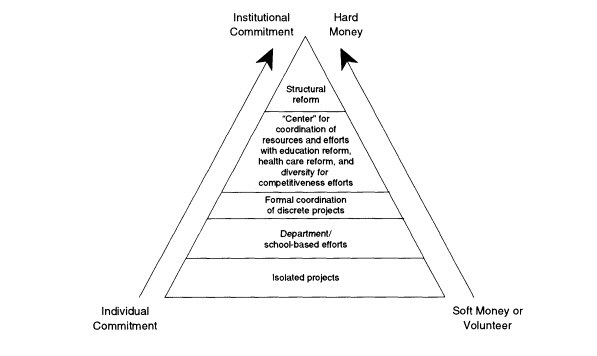

While searching for intervention programs that emphasize a systematic, integrated approach, the committee identified a model developed by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) as part of its recent report Women, Minorities, and Persons with Physical Disabilities in Science and Engineering (Matyas and Malcom, 1991). This model incorporates many of the features the committee believes essential for effective action in this arena (see Figure 4-1). Its underlying strategy is to move toward changing the structure and the environment of the system, in contrast to isolated interventions aimed primarily at helping students or faculty from underrpresented groups fit into, adjust to, or negotiate the existing system.

Figure 4-1. Model for the evolution of intervention programs. SOURCE: Modified from Matyas, M.L., and Malcom, S.M. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Physical Disabilities in Science and Engineering. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1991. Reprinted with permission.

The model's proponents contend that "only by moving from ancillary activities aimed at helping students survive the current educational climate to changing the climate in which the students are educated, can we significantly affect the participation of minorities in health and science careers" (Matyas and Malcom, 1991). Collaboration and broadened, sustained commitment from all of society's institutions and organizations that relate to the educational process must characterize future efforts to increase minority participation in professional careers.

In applying the AAAS model to the goal of broadening the landscape of minority participation, current isolated projects would become linked into a national educational network committed to ensuring an increasing and continuous supply of minority health professionals. Instead of seeking merely to remedy educational deficits at the level of the professional school, the university would establish linkages with colleges in an effort to increase the supply of well-qualified candidates for the applicant pool. The colleges would, in turn, form partnerships with several high schools, and the high schools would team up with elementary schools. At the lower levels, the system would be broad based and focused on improved science and math learning, with the understanding that students would be "lost" to other professions. Evidence suggests, however, that even under these circumstances the throughput of minority candidates in the health professions is significantly increased.

The "center" for coordination of resources could be formed within the private sector by a consortium of health professions associations, such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Dental Association (ADA), and managed in a way that would facilitate access to the many pathways that lead to health careers. Such a center could be the clearinghouse for information about resources that currently exist, but are scattered and little known. It would also help to disseminate information on national educational standards, advances in educational reform, and issues related to health care.

BUILDING THE VISION

All programs and interventions that contribute to a plan for enlarging the pool of minority health professionals must embody a number of important principles. They include improved mathematics and science learning, commitment to excellence, collaborative efforts, value on diversity, a constructive attitude for learning, culturally sensitive communications, mentoring, improved evaluation and dissemination, better resources, and attention to minority health.

Improved Mathematics and Science Learning

The committee encourages education reform that stresses a strong science and math foundation.

Over the past 10 years, efforts to strengthen the foundation for math and science learning have had disappointing results (Ratchford, 1992). Data show that students of all races filter out of science and math, so that only a fraction of interested high school students—1.4 percent—earn a Ph.D. degree. The minority pipeline, smaller to begin with, narrows even more sharply than that of the total population. As noted in Chapter 2, only 0.4 percent of minority students emerge with a Ph.D. degree in science or engineering. Studies comparing science and math students in industrialized countries consistently find U.S. students near the bottom, or dead last, bad news in a technology-driven world (Competitiveness Policy Council, 1993).

To reverse this trend, effective strategies must focus on making science and mathematics more accessible to all students, and especially to minorities and women. Establishing these competencies early in the educational process will help develop a cadre of minorities qualified to exercise choices about professional health career paths, including those of clinical practice, teaching, and research.

To understand America's poor standing in math and science, educators are increasingly pointing to the way these disciplines are taught, rather than to the inadequate ability of students. Teachers who are well trained and enthusiastic about their subject, who are effective communicators, who can advise, mentor, and encourage, are especially important in motivating minority students to pursue graduate study in science. The committee also sees the need to create a more inclusive academic environment for math and science training, one that incorporates understanding and appreciation of diversity as part of the effective teaching of these disciplines.

An academic environment that allows only the select to succeed is counter to the traditions of U.S. science and engineering. Asked by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to propose a plan to develop scientific talent, Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineer and presidential advisor, Vannever Bush, and his distinguished contemporaries responded, "We are not interested in the elect. We think it is much the best plan . . . that opportunity be extended to all kinds and conditions of men whereby they can better themselves. This is the American way; this is the way the United States has become what it is. We think it is very important that circumstances be such that there be no ceilings, other than ability itself to intellectual ambition. We think it is very important that every boy and girl know that, if he shows that he has what it takes, the sky is the limit" (Bush, 1945). Faculty members teaching science must be convinced that recruiting minority students to math and science, not weeding them out, is in the national interest and should be an important priority.

Commitment to Excellence

The committee urges a shift in perspective to an achievement model for minority education, with all educational institutions developing specific goals and implementation plans for inclusion and excellence.

Only when significant value is placed on excellence and achievement, can effective strategies and programs be realized. A growing call for excellence should join with goals of racial diversity and access. As the face of America's population rapidly changes, it is no longer appropriate to define quality and excellence in education separate from the need to prepare students for the complex economic, social, educational, and cultural issues they will face in the world of work, family, and community (Jennings, 1989). A broader orientation toward excellence pertains especially to the education and training of future health professionals who are asked to understand and relate to the special needs of patients from many different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

The importance of encouraging minorities to reach for lofty goals and giving them the confidence to achieve them cannot be overstated. Too many minority youth today are thwarted in their aspirations by perceptions that link minorities to high risk of scholastic failure. Remedial programs frequently drain the spirit of students, erode their self-confidence, and place too much emphasis on "getting through." They emphasize weaknesses. It is much better to focus on strengths.

Collaborative Efforts

For our minority youth, structures and incentives for collaborative work and study are essential building blocks for fostering improved learning of science and mathematics for underrepresented groups.

Capable students who switch out of science frequently cite science's "culture of competition" as an important factor in their decisions (Kahn, 1992). Introductory courses in the sciences often are competitive, selective, and intimidating. Instructors rarely attempt to recruit students to the discipline or to create a sense of community among them. As a result, many students sense that they are part of a group for whom there is no room in science.

In motivating more minorities to pursue careers in science, Uri Triesman, a mathematician at the University of Texas hailed for his pioneering work in teaching, underscores the importance of organizing "around the culture of science, not just ethnic identity" (Gibbons, 1992b). Studies show that a critical factor for minority students' academic success in math and the sciences is studying and discussing academic issues with other students outside class, rather than working alone and separating their academic and social lives.

Value on Diversity

The committee advocates that diversity becomes prized as a resource, characterized by genuine respect for students' varying backgrounds, talents, and learning styles.

As emphasized in this report, diversity is a resource, a criterion for excellence, as our nation moves to a new stage of economic and scientific development. By the year 2020, 40 percent of America's youth will be members of minority groups (Nickens, 1992). America cannot afford to ignore the brainpower and potential contributions of the fastest growing segments of its citizenry. All programs directed at broadening the educational pathway must do better in reaching out to students, parents, and communities of all racial and ethnic groups. Institutions at all levels should be strongly encouraged to move beyond formal requirements to emphasize the value of the unique attributes of each individual. Schools need to create and foster attractive oases of learning that both engender respect and celebrate multiculturalism and diversity.

The Right Attitude for Learning

Educational institutions at all levels must promulgate the principle that "smart isn't something you are, it's something you can become."

The perception that educational attainment in math and science is directly related to innate ability, rather than to hard work and committed effort, is challenged in a number of recent studies and surveys. A new National Urban League study indicates that intellectual development is not dependent on special innate gifts, but is more the result of hard work and organized effort (Howard, 1993). Similarly, another analysis comparing achievement in mathematics of Chinese, Japanese, and American children over a decade, showed that heightened emphasis on math and science education had little influence on academic achievement and parental attitudes (Stevenson et al., 1993). The survey indicated that U.S. parents appear satisfied with an educational system that continues to underperform because they believe, counter to the Chinese and Japanese, that innate ability, rather than effort and seriousness of purpose, determines proficiency in the math and sciences. The author concludes that the U.S. achievement gap is unlikely to diminish until, among other things, there are marked changes in the attitudes and beliefs of American parents and students about education and the contribution of hard work and effort to academic success.

Culturally Sensitive Communications

Commitment to diversity must be associated with heightened sensitivity and respect for cultural differences. Special efforts should be made to foster improved communication and understanding among diverse groups, working together toward common goals.

This report emphasizes the importance of valuing diversity as a positive human resource. Each component, every building block of any strategic plan targeted to enhancing career opportunities for minorities in medicine, must reflect this principle. Even a small investment in developing a more hospitable, inclusive environment for learning may yield significant gains in furthering the academic careers of individuals.

Research indicates that well-intentioned educational enrichment programs may fail in part because of poor communication among minority students, particularly between African Americans and teachers or faculty. A number of studies indicate that, in most cases, the academic problems of minority students are remedial and transient (Fullilove et al., 1988; Action Council on Minority Education, 1990; Kahn, 1992). Many problems are actually problems of acculturation to the medical school environment and reflect the inability of the medical school to integrate a racially diverse student body. A failure of acculturation is likely to have a strong effect on grades (Fullilove et al., 1988). For example, in considering student learning difficulties, faculty members tend to focus on cognitive factors such as background preparation, reading, and communication skills. Students, considering the same difficulties, may emphasize issues such as trust, liking, and bias. An institution's or faculty member's focus on "qualified" students may be seen as a discriminatory or biased attitude by minority students who lack the assurance and sense of self-worth that contribute so vitally to a sense of empowerment and confidence to succeed.

Encouraging minorities to pursue more advanced study in the sciences will require improving the "climate" of the classroom. All students must be made to feel they are truly valued and they can achieve academic success. This includes valuing of their culture and language and the appreciation of their individual talents. As emphasized in Chapter 2, often there is too little recognition that the inadequacies of the early education encountered by many

minority students leave them ill-prepared for a highly competitive environment.

Mentorship

The committee believes in the central role of mentoring, with its proven ability to help minorities achieve their career goals. Mentoring must become a

structured component of programs dedicated to achieving a larger presence of minorities in the health professions.

Minorities who have stayed the educational course often credit someone—a parent, teacher, or mentor—for helping them succeed. In assessing past efforts, the committee concluded that two critical components of successful programs are good teaching and mentoring, offered in a systematic way to students of all ages. Mentors guide, inform, and illuminate the way toward higher educational achievement; they help traverse the academic maze. Mentoring releases talent and energy that would otherwise lie dormant. Data, however, show that only one in eight African Americans during their graduate and professional education has ever had a true mentor (Blackwell, 1989). Lack of access to an advisor and mentor, minority or otherwise, can be a crucial barrier to developing minority faculty and minority academic leadership.

Mentoring is time consuming and often neither appreciated nor adequately rewarded. Many minority faculty members, especially at majority institutions, believe they are penalized for spending too much time with students, who may indeed make extraordinary demands on their time (Blackwell, 1989).

The scarcity of minority role models and mentors among practicing health professionals and in academe contributes to the problem of attracting minority students to the health professions and reinforces the perception that it is probably unrealistic for minority youngsters to consider this career option. Minority medical faculty have an important influence on both the number and the quality of minority students (Wilson, 1992).

The committee supports the new emphasis that many mentoring organizations are placing on outreach, training, support for mentors, and thoughtful matching of mentors and students. Ongoing commitment to mentoring requires a solid program infrastructure at the institutional level. In order not to place an undue burden on a few individuals within an institution, steps might be considered to develop a mentor-rich environment that brings minority youths into open, trusting relationships with a variety of role models and supportive professionals.

Improved Evaluation and Dissemination Efforts

Collection and timely dissemination of better data and tracking systems to measure progress should be developed. All programs must be strongly encouraged to incorporate an evaluation and reporting component. Successful elements of recruitment and retention programs should be collected and published on a regular basis and disseminated to all institutions responsible for health professions training, beginning with high school. Capacity building in

this arena will help these institutions identify and learn from the most promising and effective interventions as well as documenting those that are not working.

Major obstacles can be eliminated by expanding or replicating existing successful intervention models. Nationwide there are successful programs, but many are overlooked as a result of lack of documentation and publication. There needs to be increasing emphasis on timely dissemination of evaluation findings in a format that can be used by all the various constituencies involved in these efforts.

The committee found that only a few programs have been rigorously assessed or publicly evaluated. Programs to promote minorities in science are often managed with little oversight or accountability. Fragmentary evidence and few solid, supporting data have handicapped program assessment, the documentation of program success, and broader replication of promising efforts (Sims, 1992; Epps et al., 1993). Few assessments of the effectiveness of intervention programs in optometry, dentistry, veterinary medicine, podiatry, and nursing have been widely published (Epps et al., 1993).

Broader use of case-controlled studies to develop better information on what does and does not work in helping minorities advance through the health careers educational process should been encouraged. Such studies could strengthen the knowledge base, documenting what interventions are most effective in helping minorities achieve success in medicine and science.

The committee recommends that a national information network and clearinghouse be developed that provides timely information on activities relevant to minority health professionals.

Such a network would prove invaluable to students, faculty, and administrators. Once established, its availability should be widely advertised. Students, faculty, and mentors would be encouraged both to use it and to contribute to ongoing exchange of information. The use of electronic media and interactive communications to disseminate the latest data about educational opportunities, special programs, and financial aid would contribute significantly to broadening the interest and information base in this area.

Improved, Coordinated Resources

Further efforts to improve the targeting, coordination and administration of federal programs directed at minority health can help ensure the most effective use of scarce federal dollars. Similarly, the growing importance of states and localities in health care reform, health professions education, and health workforce policies calls for the federal government to work more closely with states and their respective academic communities in order to develop a health professions workforce responsive to the needs of different regions and

populations. Leading health professions organizations such as the AMA and ADA, with sizeable national and statewide networks, also can play an important role in improving the coordination and dissemination of public and private activities in this arena.

The committee suggests that federal funding increasingly reflect the importance of supporting programs that improve the size and quality of the minority applicant pool by focusing on early interventions.

Federal funds must continue to be made available to those schools with demonstrated excellence in educating minority students. Minority schools such as Howard, Meharry, and Morehouse struggle for financial survival while remaining responsible for the successful training and mentorship of a disproportionate share of underrepresented minority students. Incentives and rewards also should be directed at those academic health science centers willing to develop concerted efforts to increase the ranks of minority students and faculty.

A cohesive, strategic framework for broadening the pipeline for minorities in the health professions can make more effective use of existing resources. Some surveys of past efforts suggest that the survival of effective special programs is often due less to external funding than to sustained commitment by institutions of learning and other community organizations devoted to a greater minority presence (Huckman and Rattenbury, 1992; Epps et al., 1993). Nevertheless, the administration's stated objective of developing a more diverse health professions workforce as a key component of national health care reform and broadening access will require additional, well-targeted public resources.

The availability of student financial assistance must be ensured through public and private sector scholarships. More research is needed to assess the impact of rising tuition costs and a growing debt burden on the desire and ability of underrepresented minorities to consider medical school.

The high cost of medical education may be a critical factor constraining the size of the minority applicant pool and may make the more immediate financial rewards of other career paths more attractive (Ginzberg et al., 1993). Outstanding debt for indebted medical school graduates has grown significantly over the past 15 years, the result of major tuition increases and a decline in the availability of scholarships (Hughes et al., 1991). In 1992, the overall average debt of indebted medical students was over $55,000, and it was more than $58,000 for underrepresented minority students (AAMC [Association of American Medical Colleges], 1993a).

It has been shown that students actively sought by many medical schools—those from families with low incomes and from underrepresented minority groups, who are often also from poor families—end up with the most debt. Young African-American physicians have substantially more debt than

young white physicians even after parental social class and level of tuition are taken into account. To the extent that debt is an economic and psychological burden, medical schools are in the paradoxical position of increasing constraints on the very students they seek to help (Hughes et al., 1991).

A number of well-known researchers and leaders in the medical field have raised the notion that the federal government should finance medical education in exchange for a universal public service, the requirement to practice in a high-need area for a certain number of years (Hughes et al., 1991; Ginzberg et al., 1993; Petersdorf, 1993). The consideration of such a fundamental change in medical school financing remains an issue of lively debate. Short of compulsory service, however, the voluntary National Health Service Corps has much to be commended, particularly as it relates to broadening opportunities for those students who are less financially able to pursue a medical career.

Resources should be directed at faculty development, curricular revision, and program support for success in achieving greater minority participation at the university level.

Successful strategies at the academic level require faculty time, initiative, innovation, and leadership. They require resources for faculty development, curricular revision, and program support, as well as meaningful incentives for faculty who participate. While universities, as well as other educational institutions, can appeal to the humanitarian impulses of faculty by asking them to be more alert for opportunities to improve the academic climate for minority students and faculty, appeals to altruistic values work best when accompanied by rewards and sanctions.

The university environment, however, is competing increasingly for a diminishing pool of financial resources. The time has passed when a dean or a department head could simply start a new division or hire added staff to meet the demands for curricular change. Almost every initiative must be matched with a reduction or elimination in another area. Academic health centers, however, through their development offices have a unique opportunity to solicit extramural funding for diversity efforts. This may generate corporate support to attract minority youth to worksites, research units, and professional educational opportunities only a health science center can generate. Today's economic climate underscores the critical importance of heightening, at all levels, the institutional commitment to minority health professions training and the priority this issue is given by those who make funding decisions.

Improving Health Services for Minorities

Health care reform should recognize and promote opportunities both for greater minority participation in the health professions and for better health services for minority populations.

The importance and relevance of the committee's deliberations in this arena gain added impetus from today's strong national focus on health care reform and its stated goal of developing a health professions workforce more responsive to America's increasing diversity and changing health care needs. In anticipation of national reform, major changes in health care financing and delivery are being unveiled, not only at the federal level but also in the states and the corporate community. High on the reform agenda are plans for universal access, preventive care, and increased reimbursement and recognition for primary care. These changes should make it more attractive to serve currently underserved populations, usually composed of a disproportionate number of disadvantaged minorities. Heightened attractiveness, prestige, and financial awards for primary care will benefit minority physicians who have been more likely in the past to select this specialty (Council on Graduate Medical Education, 1992; Hopkins, 1992; Fox, 1993). Further, the discipline of primary care and general medicine is gaining increasing respect within academe as it fosters new, rich areas of clinical investigation, health services research, and related activities.

There is also an urgent need to attract more minority physicians to academic medicine and research.

The career pathways of practitioner, researcher, and teacher should not be in competition with each other. Underrepresentation in the health professions is even more disturbing when one looks at the paltry number of minority faculty members in medical schools. A minority faculty member in a leadership position often provides the atmosphere conducive to the recruitment, development, and retention of minority staff and faculty (Wilson, 1992; Epps et al., 1993).

Minority students should be exposed to meaningful research experiences early in their academic careers, as early as at the high school level. Such an exposure could broaden the pool of individuals potentially interested in research and teaching positions, as well as contribute to success in the health professions. In addition, minority researchers can contribute significantly to research and understanding of special conditions that contribute to poor health among minorities.

MOVING THE VISION FORWARD

How best to realize the vision for a more diversified health workforce was the central theme of the workshop conducted as part of the committee's deliberation. The 24 attendees were invited on the basis of their accomplishments, creativity, and broad perspectives in the fields of education, community development, governance, and health professions training. Many of those at the meeting had made significant contributions to the field of minority education and advancement. Through an intense, interactive process, the workshop identified several strategies described in the preceding pages that hold promise for providing the extra energy, visibility, and commitment that help bring a vision closer to reality. The committee developed blueprints for intensive but broadly based community initiatives, outlined strategies for enhancing the minority presence in academic health centers, and considered multimedia campaigns that could help capture and convey the excitement and rewards of a health professions career to minority youth.

Community-Wide Initiative

The committee recommends that foundations, through a number of demonstration projects, sponsor communities that develop their own comprehensive plan for systematic reform and implement a dynamic, multifaceted community effort directed at minority health professions training, together with a goals statement and implementation plan.

For the vision to succeed, the nation must look beyond its schools and institutions, to its communities and families. The formal education system alone cannot improve the problem of persistent underrepresentation. Future efforts will require a higher level of support among parents and all community-based leaders and organizations that contribute to education, health careers, mentoring, and the promotion of cultural diversity. Strategies that build on the strengths of community identity and culture are more likely to succeed than those imposed externally. Each community must become a place where learning can happen, a place that produces children equipped to make a wide array of choices and to succeed in the choices they make.

The committee envisions community efforts that involve institutions of learning from elementary schools through graduate training, churches, business leaders, health care organizations and providers, and other relevant stakeholders. Major emphasis would be placed on hands-on experience, outreach, and sustained mentoring from health professionals, ranging from the physician in private practice, to the rehabilitation counselor, to the visiting nurse, to the community's leading researchers

and health care administrators. A spectrum of activities would be developed and nourished, all directed to exposing minority youth and their families to the excitement, challenge, and satisfaction of pursuing a career in medicine or science. The expectation is that such community-based efforts will raise the quality and environment for science teaching, attract additional resources, and make the prospect of a health or science career a stimulating, rewarding, and feasible career pathway. The committee believes that this kind of coordinated effort can bring about lasting changes in the attitude and behavior of the community.

A significant component of the community initiative would be a structured grass-roots mentoring program, using the economic, financial, and social leverage of minority and nonminority individuals who have achieved professional standing in their neighborhoods. Many minority individuals who have been successful would welcome an opportunity to share the benefits of their experiences with future generations. These individuals would develop a structured program directed at reaching out and developing the capacities of the ''farm team," youngsters considering health careers who could benefit from ongoing support and practical advice. The committee believes that funding for such demonstration programs should come from a combination of governmental, business, and philanthropic agencies and individuals.

The committee recommends that a national information network and clearinghouse be developed that provides timely information on activities relevant to minority health professionals.

The committee believes that such a network would prove invaluable to students, faculty, and administrators. The use of electronic media and interactive communications to disseminate the latest data about educational opportunities, special programs, and financial aid would contribute significantly to broadening the interest and information base in this area. The availability of such a network should be widely advertised. Students, faculty, and mentors should be encouraged not only to use it but also to contribute to ongoing exchange of information.

The committee recommends that the federal government, the foundation world, and the private sector support an annual workshop and ongoing activities devoted to furthering the art of mentoring in the health professions.

Mentoring has proved to be a critical component of successful voyages through the health professions educational pipeline. Numerous mentoring organizations now exist; many are engaged in efforts that have garnered considerable success. However, more often than not, these kinds of activities are thinly funded. Much could be gained from providing an enrichment opportunity

for individuals seriously engaged in mentoring to meet and learn from those who have developed especially effective programs.

Commitment and Initiatives of Academic Health Centers

The committee recommends that academic health centers set a higher priority toward enhanced minority participation and maintain a high level of sustained commitment to this goal. The committee encourages academic health centers to forge partnerships with major corporations and other educational entities targeted to building programs to attract and support youths interested in the health professions.

Over the years, many of the nation's academic health centers and the Association of Academic Medical Colleges have made impressive contributions to advancing minorities in health careers. Several schools, with large minority constituency, have had a particularly striking impact. A promising new AAMC initiative, "Project 3000 by 2000," includes many elements of the desired strategic actions endorsed by the committee. The project's principal objective is to form partnerships linking academic medical centers with undergraduate colleges, local high school systems, and community organizations. Despite such worthy efforts, however, little evidence suggests significant priorities and strategies of most medical schools to increase minority enrollment and faculty development. Many programs have been established as "additions" to ongoing efforts, but they have never become part of the central, sustained mission of these institutions.

If the leadership of a medical school decides to make minority enrollment and faculty development a top priority, that school is likely to improve its record in this area. Instituting meaningful incentives and sanctions to promote desired outcomes, assigning staff time, and appointing high-level administrators to focus on this area are signs that institutions are serious about enhancing the presence of minorities in the nation's health care enterprise.

The committee recommends that community service and outreach become a fourth component of an academic health center's mission, in addition to teaching, research, and patient care. Similarly, the committee joins others in recommending formal inclusion of some level of community service among the criteria for academic recognition and advancement, in addition to the time-honored measures of scholarly and clinical achievement.

Academic health centers need increasingly to form community partnerships with local schools and colleges to nurture the curiosity and develop the talents of students who may have an interest in health careers. They need to reach out further to care for the underserved. They need to study health and illness in the community setting. Faculty leading and joining in such efforts often gain little

recognition from the traditional academic reward systems. Implementing the committee recommendation would rapidly bring to academe a new sense of priority for community-based initiatives.

The Media and Health Careers

The committee calls on the corporate sector to develop and support multimedia campaigns to attract youngsters into the health professions. The committee suggests that relevant regulatory organizations within the communications industry establish a time bank, into which a defined percentage of all radio and TV time periods be deposited. Its objective would be to reserve a portion of America's public voice for social priorities.

The imperative to enhance diversity in the health professions needs a more public voice. The media and their leaders can play a key role in creating a critical mass of support for turning minority youth "on" to science and careers in medicine. Many educators have observed that children are born scientists, endlessly questioning where things come from and how they work. The media and those who develop advertising campaigns can help educate minority youth about the fun, prestige, challenge, and rewards, both financial and emotional, associated with careers in science and medicine. Leading sports and entertainment figures, idolized by America's youth, could be enlisted to help attract minorities to careers in medicine. For example, a prominent rock star could talk about his experience with the health care system, recovering from a serious illness or an accident. A national basketball or football hero might describe the types of health care workers who helped him recover from a sports injury, commenting on their respective roles. Similarly, a leading sports or entertainment figure could talk about his battle with AIDS or another life-threatening disease and describe the kind of help and support he or she is receiving from various members of the health care team. A famous pop singer might talk about the health professions from the perspective of having to help care for a chronically ill family member. These kind of public service announcements, designed both to educate and to motivate, could help promulgate the message that a career in the health professions is rewarding, exciting, and within reach. Combining such an effort with the community-wide initiatives described above might prove synergistic and have notable impact.

SUMMARY

The committee's recommendations underscore the need to encourage continued experimentation, particularly with programs that emphasize integrated, community-based actions and sustained commitments. Strategies that include

community involvement may best be able to address the spectrum of disincentives—economic, educational, social, cultural, and attitudinal—that today deter minorities from careers in medicine and science. This agenda calls for bold and demanding measures. To achieve them will take patience, persistence, and flexibility. The vision of equal opportunity and participation of all citizens of the United States deserves nothing less.