4

What Are the Effects of the National Formulary and Related Policies on Quality of Care?

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

As health care costs have risen, organized health care delivery and financing systems have implemented cost containment measures, among them formularies and formulary systems. These measures attempt to balance control of costs of unnecessary services against appropriate expenditures for medically necessary care. The concerns Congress expressed about this balance reflect the public need for reassurance that quality of care has not been compromised by cost-conscious providers, or in fixed budget systems such as the VA. Convincing reassurance regarding quality effects of the VA National Formulary would require data relating formulary and formulary system elements to veterans ' health outcomes. Since such data were typically not available, the committee relied on other kinds of information, surrogate or secondary measures, and a few outcome results determined by analyzing hospital discharge data or monitoring the effects of formulary therapeutic or disease management guidelines. Quality measurement in general and these data specifically are discussed below.

Assessment of quality depends on an understanding of what quality is and how it can be measured systematically. The IOM has defined quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Institute of Medicine, 1990b). Quality was discussed further in an IOM policy document emphasizing that the definition assumed contributions from diverse professionals and that even with the best of professional knowledge good outcomes were not ensured (Chassin and Galvin, 1998). Most recently, the IOM has emphasized the role of medical errors, such as adverse drug events, in affecting quality of care (Institute of Medicine, 1999). The IOM

definition has been widely adopted. This definition and the contributions of professionals and medical errors to assessments of quality were accepted by the IOM committee in evaluating the VA National Formulary because they might affect the quality of care delivered to veterans by the VHA.

Classically, three elements of a health care system were said to be relevant to measuring quality of care: (1) structure, or the characteristics of the physical, organizational,and human components or resources of the system; (2) process, or the ways or procedures by which physical and human resources were used to deliver care; and (3) outcome, or the effects or results of care on the health status of patients (Donabedian, 1980). Another classification of health care quality categorized quality problems as underuse, overuse, and misuse of health care services (Chassin and Galvin, 1998). The subject of quality of care involving pharmaceutical services specifically was reviewed by Holdfield and Smith (1997). They discussed health care quality in general and also referred to the characterization of outcomes described by Kozma et al. (1993). These authors defined health quality in terms of clinical (effects on morbidity and mortality), humanistic (satisfaction and quality-of-life effects), and economic (costs of care balanced against benefits) outcomes. Because of data limitations, quality is assessed primarily by examining the structure of the VA National Formulary and formulary system in this chapter.

|

Quality Elements

|

Sources of Quality Data

Within the context of this background information on health and pharmaceutical quality of care, the IOM committee collected and analyzed data on the effect of the VA National Formulary on the quality of care for veterans. These data came from many sources, including peer-reviewed published reports, unpublished papers, conference abstracts, and conference presentations. VA sources included short IOM e-mail or telephone interview surveys of pharmacy and clinical personnel in all 22 VISNs and in many hospitals; collection of data from the VA PBM, MAP, and National Acquisition Center; personal communications from VA staff; official VA, VISN, and hospital policy and procedure documents; VA responses to questions from Congress and written questions from the IOM; VA manuals or handbooks; and the VA PBM Drug and Pharmaceutical Program Management website (www.dppm.med.va.gov). The committee asked the outcomes bureau of the VA and the VA survey team for any information that had been collected on clinical quality indicators related to the National Formulary or veterans' satisfaction with the National Formulary. Data on patient complaints

were obtained from the patients' advocates at VA facilities. The Disabled American Veterans (DAV), Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), and Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) were also asked for data on formulary issues. Information on physician perceptions of the formulary system was also sought from the National Association of VA Physicians and Dentists and the Foundation for Veterans Healthcare. Additional information bearing on quality of care came from the National Committee on Quality Assurance, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the National Pharmaceutical Council, the American Association of Health Plans, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, the National Institute for Health Care Management, Pfizer Inc., academic pharmacy experts, and the personal and institutional experiences of committee members.

QUALITY OF CARE IN THE VHA AND EFFECTS OF THE NATIONAL FORMULARY

The VA has recently reported an increased emphasis on measuring and improving varied aspects of quality of care in the VHA (Kizer, 1999). Health research and support activities aimed at understanding and improving VA quality of care have been initiated, and a number of quality of care and outcomes research centers and other activities, such as the VA Patient Safety Event Registry, are in operation at VA medical centers around the United States. These were recently reviewed and reported by Zimmerman and Daley (1997). However, the committee limited its focus to data that reflected effects of the National Formulary and formulary system. Such data proved scarce.

The committee has identified elements of the VA National Formulary that were relevant to quality effects and discusses them in this chapter. The data that were available for these elements were accumulated and analyzed. Often the committee was able only to describe elements and their possible relevance to quality rather than to analyze their effects in the VHA. As is true of other chapters in this report, some of the information and analysis in this chapter is also discussed elsewhere—for example, access to drugs in Chapter 2 and economic outcomes in Chapter 3.

In this chapter, the committee covers the implications of the VA National Formulary for quality of care, as indicated by the National Formulary's effects on structure, process, or outcomes of care, both clinical and humanistic. The committee looked predominantly at the structural elements of the formulary, including the local P&T committees, the VISN formulary committees, the VA PBM and MAP, and the quality and availability of existing drugs and drugs newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The committee also examined drug class reviews, therapeutic guidelines, the nonformulary process, therapeutic interchange policy, and drug utilization review (DUR).

The committee looked at the effect that the National Formulary and formulary systems have on process and outcomes criteria. Analysis of process is lim

ited primarily to the effects on utilization of drugs. Outcomes are limited to the results of therapeutic interchanges and adverse drug events, where there are few or no data. The committee also examined changes in the distribution of hospital discharge diagnoses associated with implementation of the National Formulary or with important changes in drug utilization caused by closing classes or committed-use contracts, where some new data were gathered. Patient satisfaction and complaints about access to needed or wished-for drugs are outcome indicators of quality. The VA does not systematically gather and analyze these data; to do so might help communicate the VA's interest in these outcomes.

In addition to the lack of data on effects on quality of care from some elements of the National Formulary and formulary system, the committee noted other analytic problems. The use of outcomes research has limitations, including the length of time needed to conduct research; the difficulties in separating effects of health care from life-styles, environment, or other confounding variables; and the infrequency of some outcome events. Separation of National Formulary effects from other effects in a large, complex, and changing health care system such as the VA may not be possible. Furthermore, effects of the National Formulary and formulary system may not be easy to dissect from effects of the VISN or local formularies and formulary systems, as noted here and elsewhere in this report. This, however, is less of a concern since all the formularies were treated as part of the National Formulary. Nevertheless, the committee concluded that there was sufficient information to allow discussion and some inferences about formulary influence on the quality of health care to veterans.

PHARMACY, CLINICAL, AND FORMULARY PROGRAM ELEMENTS RELEVANT TO QUALITY OF CARE

Clinical Pharmacy

The development of clinical pharmacy services and the redefinition of the scope of pharmacy practice in the VA that occurred in the 1990s when the VHA was reorganized into 22 VISNs and redirected toward ambulatory and primary care has been described in a number of reports (Anonymous, 1988; Gray, 1992; Kizer, 1999; Ogden et al., 1997; Portner et al., 1996). These developments created an expanded pharmacy program and services. VA PBM activities involved the implementation of drug treatment guidelines, the National Formulary, and national contracts. Pharmacists assumed greater involvement in patient education activities and monitoring therapies. They increasingly joined clinical care teams in clinical settings and provided advice on pharmaceuticals and the formulary system to other health care professionals. Some special programs were initiated in which pharmacists monitored adherence to specific clinical guidelines in situations where national (Joint National Committee, 1993) and VA ( http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/treatment1.htm) drug treatment guideline compliance is poor (Siegel and Lopez, 1997). Through academic detailing, as described by

others (Avorn and Soumerai, 1983), and other interventions involving education and cooperation with prescribing physicians, guideline compliance was improved. This significantly enhanced the quality and cost-effectiveness of care for hypertensive and diabetic veterans (J. Lopez, personal communication, VISN 21, 1999; Meier et al., 1999; Siegel et al., 1999). These structural enhancements in some cases are shown to enhance the quality of drug therapy for veterans and, in general, presumably would have a positive effect on quality of care. The committee did not audit the performance of these new roles, but clinical pharmacist advisers have had clear and positive effects on quality (for example, fewer adverse drug events, improvements in drug selection and dosing, and cost savings) in other systems when evaluated in research protocols (Baciewicz et al., 1994; Haig and Kiser, 1991; Hatoum et al., 1988; Leape et al., 1999).

Some changes in pharmacy practice in the VHA preceded and were to some extent independent of the National Formulary so that improvements in quality of care due to improved numbers, training, or activities of pharmacists in the VHA cannot always be related directly to effects of the National Formulary. Performance of VA clinical pharmacists was reported by Gray (1992) early in the 1990s to positively affect proper dosing, indications for drug treatment, laboratory monitoring, and nonformulary requesting. This investigator at the Long Beach VA also described the 1990 implementation of a computerized system for monitoring and reporting pharmacist-initiated clinical interventions. Pharmacists play an important role in the implementation of the National Formulary, and improvements in pharmacy services and expansion of their pre-National Formulary roles probably have affected the National Formulary positively. To the extent that better pharmacy services affect and participate in the implementation and management of the National Formulary and formulary system, they are relevant quality structural elements.

P&T COMMITTEES

The introduction to this report describes the history of P&T committees in hospitals and other settings such as MCOs. Later in Chapter 1, the establishment and some of the details of P&T committees in VA hospitals are reviewed. Today, private-sector P&T committees have evolved into hospitals' or other organized health systems' primary organizational tool to evaluate and select approved (or reimbursable) medications for inclusion on the formulary. An effective P&T committee has educational, communicative, and advisory roles (ASHP, 1964, 1992) and participates in ongoing review of formulary selections for effects on quality of drug treatment as recommended in guidelines of the NCQA (UM10). It is composed of a cross section of physicians, pharmacists, and nursing representatives, usually with 8–12 members. Most P&T committees meet monthly and have formal procedures for considering formulary additions. P&T committees, through their communications, serve as the primary link between the pharmacy and the medical staff. Traditionally, hospital P&T committees have been composed mostly of physicians (Rucker and Visconti, 1975). The

primary goals of a P&T committee are to enhance the rational use of drug therapy and, at the same time, to minimize social and institutional costs.

As noted elsewhere in this report, VA policy requires VA hospitals to establish P&T committees that meet the standards of the JCAHO * and the ASHP. The P&T committees' functions are performed by the medical staff in cooperation with pharmacy and nursing services and management. Traditionally, a pharmacy service representative serves as the VA facility's P&T committee secretary and is responsible for the minutes of the committee meetings. Some VA P&T committees are said to consider staff requests for nonformulary drugs, ensure that mandatory contract sources are honored, develop and revise the facility formulary, monitor adverse drug events, ensure mandatory generic prescribing or substitution, and design and implement local therapeutic interchanges and approve pharmacist substitutions, among others (VA Manual, M-2, Part 1, Chapter 3, Clinical Programs, Pharmacy and Therapeutic Committee, Dec. 13, 1993). These VA committee functions are not dissimilar to those of P&T committees in other sectors of health care. The role of most VA P&T committees in formulary management is less clear, because in 16 of 22 VISNs that particular VISN's formulary is required in all facilities.

The IOM committee did not audit performance of the P&T committees at the 172 VA hospitals. These committees should be an important structural element in the quality of drug treatment and formulary effects at the local level. They preceded consideration of a National Formulary by decades, however, and they carry out functions in addition to the National Formulary. They would also appear to be the primary place where nonmanagement VA physicians can interact with the National Formulary, or at least the VISN and local formulary and formulary system, in an influential way, although this interaction may be weakened in VISNs with a policy that requires a single VISN-wide formulary. The committee could not determine if VA P&T committees are always chaired by physicians and made up mostly from the medical staff, although this is the generally accepted model. This has implications for local physician acceptance of the National Formulary and the effectiveness of formulary operations (Carroll, 1999).

The reorganization of the VA in 1995 divided the VHA into 22 VISNs. VISN formulary committees were established as an interface between the local and national units. The formulary committees have representatives from the facilities in their region, but they may differ in the ratio of physicians and pharmacists. Formulary committees average 15 members with a range of 6–28. The membership is primarily pharmacists (52%; range, 33–100%) and physicians (44%; range, 0–65%). Nurses are included in only six VISNs. In an occasional VISN, additional personnel are included, such as representatives from administrative units. One VISN formulary committee has no physicians, four have quite distinct minorities of physicians, and overall, pharmacists outnumber physicians.

|

* In 1993, the JCAHO ceased setting standards for P&T committees and began evaluating final outcomes rather than processes. The VA, however, still uses JCAHO P&T standards as medical guidance in hospitals. |

This membership structure may weaken the role of VA P&T committees as mechanisms for medical staff management of quality drug treatment and as visible and important symbols of that role (see Table 4.1). A recent survey by the AMCP identified physician membership of PBM P&T committees at 63 % on average (Table 2.1 ).

Some VISN formulary committees may function as VISN P&T committees. Most of these VISN committees (16 out of 22) have a policy of a single network-wide formulary to control regional drug use. The role of the VISN formulary committees has not been standardized, nor do they have membership guidelines. This has resulted in some VISNs formulary committees' acting as an additional P&T committee and others evolving toward miniature PBMs. The latter committees could function more as formulary managers for VISN administrations than as medical staff drug treatment committees, and their composition with few or no physicians could reflect this role. National VA policies have allowed VISNs reasonable latitude in implementing and enforcing VHA policy. In general, written VISN policies were not found describing or specifying how individual VISNs implement national policies at the regional or local level. Implementation of most formulary policies appears to be somewhat informal, although VISNs are specific about nonformulary policy (as required by VHA Directive 97-047) and addition of drugs to the VISN formulary. National committed-use contract adherence in their regions, is also a responsibility of VISN formulary committees.

In focusing on budgetary matters, such as controlling items on VISN and the majority of local facility formularies, nonformulary policy, and contract adherence, VISN committees assume roles as little PBMs. In contrast to some P&T or formulary committees of traditional private-sector PBMs, the VISN committees, like traditional hospital P&T committees, do not include noninstitutional (that is, non-VA) members. VISN formulary committees tend to be made up of VA pharmacists who have a vested interest in the pharmacy budget. Since VISN budgets are allocated on a per capita basis and are fixed, pharmacy managers are responsible for control of their budgets to ensure that funds for other care are not jeopardized. There are no formal studies of VISN formulary committees' effects on veterans' care. The necessary, but not sufficient, conditions for producing higher-quality effects would be to maintain a quality listing of drugs, ensure access to drugs through a smoothly functioning nonformulary process, and provide competent management of the National Formulary at the regional level.

VISN formulary committees have evolved since their inception toward PBM functions. The committees vary in their membership. Inclusion of more physician representatives on some committees could improve acceptance by VA physicians with the implications this might have for effectiveness and quality of the National Formulary. The expertise of pharmacists will remain integral to the performance of these committees, however, and other aspects of the National Formulary system are probably more important to physician acceptance.

THE VA PBM COMPLEX

Private-sector pharmacy benefits managers have evolved from claims payers for employer plans, MCOs, and government-funded programs with a pharmacy benefit to more complex organizations that maintain formularies, have generic and therapeutic interchange policies, disease management, and other educational programs, and perform DUR. PBMs achieve cost-effective drug treatment through their cost-containment strategies, pharmacy networks and mail-order pharmacies, drug price negotiations aided by their formularies, and tiered copayments, as well as through careful review and guidance by the clinical staff. These and other activities of PBMs are discussed in Chapter 2 of this report (Friedmann and Hanchak, 1999; Gibaldi, 1995; Kreling et al., 1996; Navarro and Cahill, 1999; Schulman et al., 1996; Taniguchi, 1995; WyethAyerst, 1998). In eight of the largest U.S. PBMs, external representation in addition to internal staff on P&T or formulary committees is the rule. Private-sector PBM committee members can range from 1 outside physician with no vote to 17 outside physicians with full voting privileges. Usually from one to five pharmacists employed by the PBM round out the committee. Some PBMs have multiple local P&T committees and a central committee with local representation (Jones, 1998).

The VHA reorganization authorized and funded the creation of VISNs and VISN formularies, planning for the National Formulary, a VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group, a Medical Advisory Panel, and a VISN Formulary Leaders Committee. These are described briefly in Chapter 1 of this report. The VA PBM planning document (Pharmacy Benefits Managemerit: A Valuable Product Line, [1995]) describes VA PBM organization and functions. This document asserts that a VA PBM “has the advantage of having both clinical and pharmacological information by patient. The result is a PBM which truly can have a very positive effect on both the economics and quality of care we provide.” For further comment on VA data, see Chapter 3 of this report. The MAP was described as a standing body of 10 practicing field-based physicians appointed to 2-year terms by the Undersecretary for Health on recommendation of the VA PBM. Currently it is comprised of 1 Department of Defense (DOD) and 11 VA physicians. According to the VA, the VA PBM, MAP, and VISN formulary leaders, acting together, are responsible for National Formulary addition and deletion decisions. These bodies are central structural elements related to the National Formulary's effects on quality of care, and the quality of their management and clinical decisions regarding the formulary and formulary systems

|

VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group: A pharmacy benefits manager created by the VA reorganization of 1994–1995 to administer the drug benefit of the VHA. Medical Advisory Panel: A committee of practicing physicians appointed by the VA Undersecretary for Health that advises the PBM on medical drug issues for the VA National Formulary. |

TABLE 4.1 Management of the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) Formulary

|

VISN Formulary Committee Membership |

|||||

|

VISN |

VISN Formulary Relationship to Local Formulary |

Pharmacist |

Physician |

Other |

Addition of New Drugs to the VISN Formulary |

|

1 |

Same |

13 |

10 |

0 |

Local or VISN |

|

2 |

Same |

7 |

13 |

0 |

Prescriber or local |

|

3 |

Same |

9 |

7 |

0 |

Local a |

|

4 |

Same |

19 |

7 |

1 |

No information |

|

5 |

Same |

6 |

9 |

3 |

Local |

|

6 |

Same |

8 |

0 |

0 |

Local |

|

7 |

Same |

9 |

7 |

0 |

Local a |

|

8 |

Minor restrictions |

6 |

8 |

0 |

Local a |

|

9 |

Can differ |

7 |

4 |

0 |

|

|

10 |

Same |

10 |

5 |

0 |

Local |

|

11 |

Same |

7 |

7 |

0 |

Local |

|

12 |

Same |

7 |

7 |

0 |

Evaluated at FDA-approval time |

|

13 |

Same |

6 |

5 |

0 |

Local |

|

14 |

Same |

4 |

5 |

0 |

|

|

15 |

Same |

9 |

8 |

0 |

Local |

|

16 |

Can differ |

7 |

5 |

1 |

Local a |

|

17 |

Minor restrictions |

3 |

3 |

1 |

Local |

|

18 |

Same |

8 |

7 |

0 |

Local |

|

19 |

Same |

7 |

7 |

0 |

Local or some evaluated at FDA-approval time |

|

20 |

Minor restrictions |

3 |

8 |

2 |

Prescriber or local |

|

21 |

Same |

7 |

6 |

0 |

Prescriber or local |

|

22 |

Minor restrictions |

8 |

6 |

1 |

Prescriber or evaluation at FDA-approval time |

|

NOTE: Local = local pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee request for VISN formulary addition; prescriber = anyprescriber can generate a request for VISN formulary addition independent of the P&T committee; VISN = VISN formulary committee can generate addition request to VISN formulary. a VISN has a year wait on review. b Additions considered in response to local physician-, P&T committee-, or VISN-generated requests. c VISN does not generally add new drugs unless they are first added to the National Formulary. |

|||||

is as important to the VA formulary as private-sector PBM management is to private formularies.

The VA PBM, MAP, and VISN formulary leaders are appointed by senior VA officials and do not include medical staff who could be seen as representatives of ordinary practicing VA physicians, outside expertise, or veteran consumers. The local facility P&T committee is, therefore, the focus of nonmanagement practicing physicians in a National Formulary and formulary system committee structure that is also devoid of formal patient input. Even at this level, it is not clear how much influence local physicians have on formulary listings or structure since in many cases such decisions appear to be made at the VISN level. Two surveys have suggested that a distinct minority of VA physicians feel some dissatisfaction with the VA formulary system. The ways the VHA finds to give representative physicians a sense of participation in the formularies, or the knowledge that their management of drug treatment is modified only by science-based controls, fairly implemented, and responsive to the clinical needs of veterans, may have implications for VA physician acceptance of, and satisfaction with, the National Formulary. Physician satisfaction and acceptance may influence how the National Formulary affects quality of care. The IOM committee assessed VA PBM performance by examining the quality of the formulary, additions of drugs, drug class reviews and therapeutic guidelines, the nonformulary process, therapeutic interchange policy, and other elements of the system that affect quality. These and other factors are discussed below and in other chapters (for example, Chapter 2) of this report.

Additions to, and Quality of, the National Formulary

The addition of existing and new FDA-approved drugs to the National Formulary and the overall quality of drugs on the present formulary are important factors in the availability of drugs and thus in quality of care. Because the availability of drugs is related to the restrictiveness of formularies, addition of new drugs to the National Formulary is taken up at some length in this report's Chapter 2. VA policy on considering the addition of new FDA-approved drugs requires a 1-year wait, except in cases of significant 1P (FDA priority) category drugs. In practice, the VA has added drugs primarily for HIV/AIDS treatment recently. In theory, veterans could still have access to new drugs if they were added to VISN or local formularies or if a smoothly working nonformulary process made them easily available. In practice (see Table 4.1), two VISNs do not add drugs unless they are first added to the national list, and these and four other VISNs also have a policy of a 1-year wait for new FDA approvals. Only three VISNs actively monitor FDA approvals, and they consider additions requested by their formulary committee, local P&T committees, or VA prescribers.

All local P&T committees can recommend existing drugs to the VISN formulary committee for inclusion in the VISN formulary. In four VISNs, an individual prescriber can request inclusion of a drug without local P&T committee approval. In one instance, a VISN (VISN 2) collected utilization data from all

stations to explore whether nonformulary drugs being used locally were candidates for VISN review. The VISN review processes are similar. A form is available to make a request and provide supporting relevant information. This form is filled out either by the prescriber or by the local P&T committee and is sent to the VISN formulary committee, along with a drug review. This information and the VISN reaction are generally circulated to local facilities for a 30- to 60-day comment period. VISN decisions can be reversed if warranted by comments, but only one VISN (VISN 22) has an appeals process in place.

At the national level, drugs can be considered and added to the National Formulary after VISNs suggest a review. If multiple VISNs (usually five or more) add an existing drug or a new FDA approval, the drug will be reviewed at the national level for addition to the National Formulary. As discussed in Chapter 2, the National Formulary adds few drugs each year and considers relatively few new FDA approvals, adding primarily new HIV/AIDS drugs only. The committee is aware of complaints from veterans and from prescribers, as reviewed below.

There is no accepted standard for the number of items on a health system formulary, except that listings should reflect the judgment of the medical staff acting through a P&T committee (ASHP, 1992). As discussed in the chapter on restrictiveness, the VA National Formulary appears to be of reasonable size in comparison to other health system formularies, although it has fewer representatives in a number of drug classes than MCO or Medicaid formularies. The committee was aware of some past efforts to assess the quality of drugs on formularies (Rucker, 1982, 1982a). In these reports, the author listed drugs considered of questionable quality. Rucker has also criticized formularies for listing fixed combination drug products. More recently, GAO identified drugs considered inappropriate for the elderly (GAO, 1995). The P &T and medical experts on the IOM committee reviewed the VA national list against these lists of questionable drugs and questionable combination products, and concluded that the National Formulary contained few such products. Drugs included on the National Formulary appear to meet reasonable standards of numbers, variety, and quality based on committee members' professional judgment and experience. Timely consideration of new FDA-approved drugs is discussed in Chapter 2 of this report.

POLICIES AND PROCEDURES

Drug Class Reviews

Standards for drug class reviews have evolved since 1981 when ASHP published a comprehensive description of the elements of a drug class review (ASHP, 1981). The drug class review was originally a tool for the pharmacy administration to standardize therapies and reduce inventory. As formularies began to be used to manage drug benefits, drug class reviews came to provide comparative analyses of knowledge about a drug and drug class and the applicability of this knowledge to accepted medical practice. A drug class review is an

important mechanism by which a formulary system evaluates and selects from among drugs and drug products those that are considered most useful in patient care. Choosing in this way has quality implications, but it also allows a formulary system to negotiate prices of selected drugs based on anticipation of volume use, as observed elsewhere in this report.

A review can be organized into four primary areas: (1) identification of the organization and reviewers; (2) objective of the review; (3) recommendations of the review; and (4) references. Reviews should also include absolute and relative data on pharmacokinetics, clinical trials and outcomes, safety and efficacy, dosing regimens and titration, routes of administration, multiple indications, and cost and pharmacoeconomic analyses. Detailed standards and guidelines for performing drug class reviews have been reported a number of times, for example, by a group purchasing organization, such as Premier, or in the literature (ASHP, 1981; Basskin, 1998; Langley and Sullivan, 1996; Lipsey, 1992; Majercik et al., 1985). VA drug class reviews generally conform to these primary and specific criteria, although they sometimes omit a specific item(s) or a specific section, for example, pharmacoeconomic analysis, which also occurs in the private hospital sector (Majercik et al., 1985). harmacoeconomic analyses are useful because, among other reasons, some lower-priced classes may require more resource intensive management or provide lower-quality results.

Conclusions drawn in VA reviews are based on current research and consultation with subject matter experts. Occasionally, other factors that may affect quality of care are assessed. For example, a VA drug class review of ACEIs recommended addition of two long-acting members of this class to the National Formulary because patient compliance is improved on once-a-day dosing, but it also provided for a shorter-acting agent (captopril) for frail patients in need of slow titration. Since decisions on the recommendations of drug class reviews are made jointly by the VA PBM, the MAP, and VISN formulary leaders, these recommendations are likely to be implemented in the National Formulary.

IOM committee members with experience and expertise as physician leaders of P&T committees and as responsible officials of MCOs and PBMs examined the conclusions and recommendations of nine VA drug class reviews (ACEIs, alpha blockers, prokinetics, LHRHs, CCBs, H 2R blockers, HMG CoA RIs, PPIs, and SSRIs). In all cases, the drugs recommended by the review were included on the National Formulary (July 1999 version). In two cases, CCBs and H2R blockers, the National Formulary listed more agents than the minimum recommended by the review. The committee concluded that VA reviews, both as stand-alone reviews and in comparison to reviews in private-sector organizations, were of high professional quality and reached recommendations based on scientific evidence and sound interpretation of clinical data. The experts on the VA committees look at the safety, efficacy, and cost of particular products. They can then make decisions that have a reasonable scientific and clinical basis and also may affect utilization, market share, and price negotiations. The National Formulary accurately reflects the results of good quality assessments of drugs and drug classes.

Clinical Guidelines and Drug Utilization Reviews

Therapeutic or clinical guidelines are a means to decide among, and educate clinical practitioners on, preferred management of diseases and clinical conditions. In 1990, the IOM examined clinical guidelines and identified eight attributes that are essential for guideline quality: validity, reliability, clinical applicability, clinical flexibility, clarity, multidisciplinary process, schedule review, and documentation (Institute of Medicine, 1990a). IOM committee members referred to these criteria in addition to their own expertise and institutional experience with guidelines in assessing the quality and effectiveness of VA therapeutic guidelines.

The VA PBM website has documented the process of developing guidelines, including the participants in the process. Guidelines are said to be updated regularly, although the exact periodicity is not specified. They are clearly written, and interested or key clinicians can review and comment on their appropriateness. Guideline treatment recommendations are consistent with current recommendations of outside organizations. For example, the guideline on congestive heart failure reflects recommendations of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Health and Human Services (see http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/DSMCHF.htm). The guidelines are also tailored to the older VA patient population. In the guideline for the pharmacological management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), special problems in theophylline use in older patients are discussed. The IOM committee reviewed all of the clinical guidelines found at the VA PBM drug and pharmaceutical product management website (www.dppm.med.va.gov). The committee concluded that the VA drug treatment guidelines are of high quality, are based on current scientific and clinical research data, and are reliable and equivalent to similar documents in the private sector.

The committee sought evidence that VA guidelines were known to, and used by, VA physicians caring for veterans. As noted earlier, the guidelines are available on the VA PBM website and are updated periodically. Based on interviews of VA physicians by IOM staff, they are also widely distributed via mail, e-mail, weekly meetings, and one-on-one counseling sessions. It is not known, however, to what extent VA physicians consult the guidelines in their daily practice. Responses of VA physicians to the IOM were varied. Most had reported looking at the guidelines, but not whether their clinical decisions had been affected. Some suggested that the guidelines were useful in the teaching of residents.

There was some evidence that implementation of guidelines was monitored and assessed. In general, an increase has been reported in the documentation of appropriate use of inhalers for COPD, in plans to manage cholesterol in patients with heart attacks, and in charting appropriate therapies in ischemic heart disease (beta-blockers) and diabetes (Kizer, 1999). It is hard to tell whether this reflects changes in charting or actual practice. Some specific programs to monitor and encourage compliance with guidelines have been implemented. At the

national level, a DUR has recently been completed to evaluate the appropriate use of PPIs. Facilities that had the highest percentage of twice-daily dosing were identified for review. Recommendations for each individual patient were sent to the facilities in question.

At the VISN level, monitoring has varied. A program in VISN 21 to monitor antihypertensive drug treatment was described earlier. A DUR program to monitor appropriate use of troglitazone, a third-line agent for the treatment of diabetes eventually recalled by the FDA, was reported to IOM from VISN 22. Although proper indications for prescribing this drug were followed, monitoring of liver toxicity was spotty. A requirement for documentation of liver function test results on prescriptions improved compliance with monitoring for this adverse drug reaction. Some other VISNs have mounted similar DUR efforts, although most VISNs do not carry out formal DUR programs, presumably because of constrained resources. DUR programs are required at hospitals, but IOM did not survey VA hospitals' DUR programs. A few hospitals were queried and they followed JCAHO recommendations for establishing DURs. That is to say, they were looking at high-risk, high-use, and costly drugs as candidates for DURs. In some situations, the facilities would share their outcomes, either informally or formally, with other facilities in their VISN. Clinical guidelines and DURs are tools employed by the VA for improving quality of care, but programs that promote the use of guidelines and supplement them with DUR programs as appropriate would enhance the effectiveness of these tools.

The Nonformulary Process

When hospitals or organized health systems develop formularies, drugs in a class are evaluated, appraised, and selected that are at least equally, and preferably more, effective and safe and have at least the same, or preferably higher, probabilities of successfully treating most patients than other class members. Drugs that are essentially equivalent may be selected because, based on price, they are more cost-effective. Some patients in any population will have difficulty with the formulary drug(s) because of therapeutic failure, allergy, or other adverse reactions or contraindications. For this reason, any restricted formulary must have a mechanism to provide drugs that are not included or covered. A nonformulary process is a universally required component of a formulary system and is part of systems in MCOs and PBMs (AAHP, 1998; ACP, 1990; AHA, 1974; AMA, 1994; ASHP, 1983; Dillon, 1999). Prior to the introduction of the National Formulary, VA hospitals had restricted formularies and established procedures for obtaining nonformulary drugs. With the establishment of the National Formulary, the VA did not implement a standard national procedure, but rather outlined criteria in VHA Directive 97-047, and required VISNs to develop and implement a process in each region. VA criteria are consistent with the policies and criteria of most managed care organizations (Dillon, 1998). The VA is unlike many other organizations and Medicaid in that very rarely are drugs cluded, that is, unavailable even through a nonformulary process.

VHA Directive 97-047 requires the following: (a) A nonformulary request process must exist at each VA medical treatment facility; (b) This process should ensure that decisions are evidence based and timely; (c) Nonformulary drugs should be approved under the following circumstances —(1) contraindication(s) to the formulary agents, (2) adverse reaction to the formulary agents, (3) therapeutic failure of all formulary agents, (4) no formulary alternative exists, (5) the patient's previous response to a nonformulary agent and the risk associated with a change to a formulary agent, (6) other circumstances having compelling evidence-based clinical reasons; (d) Nonformulary approvals should require a reevaluation of the approval based upon clinical response; (e) Each VISN will identify key nonformulary approval components and establish a process to analyze and trend the information at the VISN and local level; (f) In therapeutic classes where national standardization contracts have been awarded, VISNs will report to the PBM quarterly the justification for nonformulary drug utilization. A template for the report will be provided to VISN formulary leaders by the PBM. As noted elsewhere, information from [e] and [f] is not available.

Since national policy does not dictate a specific nonformulary process, either a VISN or a local facility (depending on VISN policy) can design a procedure that is consistent with directive criteria. As a national average, 3.45% of all prescriptions dispensed by the VHA are for nonformulary drugs. However, this can vary from a fraction of 1% to about 30% by institution (based on closed-class nonadherence reports) depending on the local nonformulary process. These data depend on the national computerized system tracking drug dispensing and formulary adherence and are likely to be accurate. Comparisons of these percentages with percentages in hospitals and MCOs have been detailed in Chapter 2 of this report. In general, VA nonformulary dispensing volume is a comparatively lower percentage.

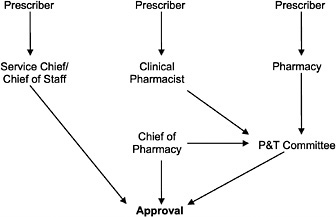

In a preliminary investigation, the IOM determined that there were many variants of approval processes in use (see Figure 4.1 for some common variants). The simplest and quickest process was a prescriber telephone call to the pharmacy or to the chief of staff to obtain a decision. More complicated and time-consuming processes involved completion of a form (of varying complexity) by the prescriber, which was submitted to the pharmacy for review, followed by a decision by the local P&T committee.

In response to a congressional inquiry, the VA PBM conducted a survey of all institutions in each of the 22 VISNs in December 1998. Survey results were reported to Congress in early 1999. The survey asked the physician chair of each P&T committee to rate the nonformulary system before and after implementation of the National Formulary. The process was rated “easy” (as opposed to “difficult”) prior to the National Formulary by 84%. After implementation of the National Formulary, 97% of physician chairs gave the process an “easy” rating. The IOM committee noted that in many institutions the P&T committee is a step in the nonformulary approval process. The P&T chairperson cannot be considered a disinterested rater, and the rating itself is not an objective or quantitative one and is undoubtedly subject to varying interpretations. The time for approval

FIGURE 4.1 Variations of the VA nonformulary approval process.

was reported to decrease from 43 to 27 hours after the National Formulary became operational. The survey also reported that 88% of requests were approved. This compares with 70 to 90% approvals in other public-and private-sector formulary systems (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998; Jones, 1998; Kreling et al., 1996; Phillips and Larson, 1997; Schweitzer and Shiota, 1992; Sloan, 1989).

Many VA facilities have an informal nonformulary process, as noted in the minutes of the VA PBM Research Steering Committee meeting of March 1998. In a follow-up to its preliminary investigation, the IOM surveyed institutions in all 22 VISNs to explore qualitatively this informal system and its implications. Although institutions in all VISNs were queried, the total numbers (22) were too small to constitute a statistically valid sample. Nevertheless, the IOM survey discovered a range of interactions between physicians and pharmacy teams resulting in positive or negative nonformulary decisions that may not be documented (see Table 4.2). Historically, one large VA medical center reported that 7.7% (about 25 per month) of interactions between clinical pharmacists and physicians in clinical settings involved nonformulary requests (Gray, 1992). These were not tracked before the introduction of the National Formulary. Such interactions continue and are unlikely to be documented now. If this is prevalent, the nonformulary study reported to Congress may overestimate the percentage of requests approved.

Currently, in some facilities, if a prescriber sends a prescription for a non-formulary drug without a nonformulary request form, the pharmacist will call the physician to suggest formulary alternatives. In some institutions, the pharmacists will make similar calls even if a form is submitted. Although these are nonformulary requests, they are not always reflected in the approval numbers; that is, a change to a formulary item is not always counted in the approvals or

denials for the month. In other institutions, physicians are called about denials and only approvals are tabulated. In still other institutions —for example, special units such as spinal cord injury centers—special negotiations by Paralyzed Veterans of America representatives, usually at the center or facility level, occasionally at the VISN or even undersecretary level, result in enhanced availability of sometimes hard-to-get items. These include supplies (which were listed in the VA National Formulary, at least in part, at the behest of the PVA). Of course, this kind of representation or sponsorship is not always available to most veterans (H. Bodenbender, PVA, personal communication, 1999).

The IOM committee appreciates the advantages of an informal system in flexibility and speed of response and the difficulty of recording informal discussions or advice. Spotty documentation of the process resulting from informal, or more formal but still unrecorded, interactions casts doubt on the accuracy of nonformulary request numbers and approval percentages, however. This may diminish confidence in the system. An informal and variable system also may result, in some instances, in processes that appear arbitrary or overly responsive to budgetary rather than medical conditions. In some facilities, the physician time necessary for multiple nonformulary requests, or the time spent if P&T committee review is required, might be perceived as a barrier and potentially detrimental to quality care. The nonformulary process appears to differ considerably across the VHA. It is often informal and unrecorded in national statistics.

TABLE 4.2 Results from IOM Exploratory Inquiry into the Nonformulary Approval Process

|

Nonformulary Process |

Not Recordeda (n = 22) |

|

Prescription is sent to the pharmacy without a form and is changed to a formulary item |

22 |

|

Prescription is sent to the pharmacy without a form and is denied |

6 |

|

Prescription is sent to the pharmacy without a form, and is denied, form is sent in but is denied. |

0 |

|

Prescription is sent to the pharmacy without a form and is approved |

5 |

|

Form is sent in, prescriber called, item changed to formulary item |

9 |

|

Patient or drug representative initiates the nonformulary process |

6 |

|

Prescriber and pharmacist talk about a nonformulary drug, but a formulary item is prescribed |

19 |

|

Nonformulary item is discussed and approved, no form is generated |

6 |

|

Nonformulary item is discussed and not approved, no form generated |

4 |

|

A nonformulary item is discussed, and denied, a form is submitted and denied |

1 |

|

Prescriber or facility is noncompliant |

1 |

|

a Number of VISNs in which a facility might not record a nonformulary request in its monthly statistics. |

|

Examination of nonformulary forms and some anecdotal reporting suggest that delays and burdens in obtaining nonformulary drugs also may vary and in some cases may be problematic. The current system has not provided reassurance about delay or access problems. The committee concluded that the National Formulary would be seen as fairer and more responsive if the nonformulary system were revised and simplified and improvements in accurate and consistent reporting were made. Among these, the VHA should consider pilot tests of non-formulary processes that include, for example, budget feedback to prescribers, request tracking and education through service chiefs analogous to academic detailing, or exploration of retrospective corrective discussions with prescribers who abuse the system.

Therapeutic Interchange, Policy, and Results

Therapeutic interchange policy and practice are reviewed in Chapter 2 of this report. In this chapter, the committee briefly discusses issues relevant to quality of care including policy direction, evidence for problems in VA interchanges, the relationship to a flexible nonformulary process, and prescriber control. Although the National Formulary and formulary system, like systems in most private-sector MCOs, PBMs, and hospitals (Doering et al., 1988; Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998: Nash et al., 1993; Novartis, 1998, 1999; Reeder et al., 1997; Sloan et al., 1997; Wyeth-Ayerst, 1998) contemplate, therapeutic interchange in response to drug use criteria, formulary listings, or national standardized contracts, there is no national policy on the process of interchange. The VA PBM, MAP, and VISNs have left policy and procedure to local facilities, although directives leading to interchange often originate at the national or VISN level. Reports of therapeutic interchange at VA facilities describe various procedures and results. Overall they are reassuring (see references cited in Chapter 2), but they suffer from analyses of too-small numbers, often with too-short or otherwise less-than-adequate follow-up and other methodological shortcomings.

Interchanges generate a measurable level of dissatisfaction among VA physicians (Glassman et al., 1999; Yankelovich Partners, 1999) and complaints from patients (see below). Although current published reports in the medical literature, unpublished documents from VA facilities, and expressions of physician and patient dissatisfaction from surveys and patient advocate data, do not constitute compelling evidence of quality problems, they raise questions for exploration and suggest possible responses that might be taken by the VHA. Therapeutic failure of the formulary therapeutic alternate, medical complications, offsetting costs caused by extra visits and tests, and patient and physician complaints have all been discussed earlier (see Chapter 2). Elsewhere in this report it is suggested that desirable consistency in therapeutic interchange might include assurance of physician and patient education and advance notice, attention to drug treatment compliance, and provision for exceptions based on characteristics of at-risk patients, among others. The responsiveness and consistency of the local nonformulary process to problems that arise in interchange programs

might also reassure patients and prescribers that quality considerations will be given priority.

VA P&T committee policy permits pharmacists to prescribe therapeutic alternates in a program of therapeutic interchange when authorized by the local P&T committee. The fact that the permission of prescribers may not be sought and often is not obtained at the time of dispensing an alternate emphasizes the desirability of ensuring prescriber (and patient) education and acceptance of the purposes of the National Formulary and formulary system to avoid unnecessary dissatisfaction and possible quality problems. Higher-quality investigations of interchange programs would engender greater confidence in VA study results. Furthermore, measures that promote physician understanding and acceptance of, and participation in, the formulary system and interchanges could diminish physician (and patient) dissatisfaction. Surely, if veterans receiving a drug on a long-term basis are subject to interchanges multiple times or too often because of changes in the formulary or committed-use contracting, there will be effects on acceptance and compliance, and there may well be changes in the effectiveness of treatment. In short, quality of care and possibly health outcomes will be affected. The VA has no policy on frequency, or limits on the number, of interchanges for veterans.

EFFECTS OF THE NATIONAL FORMULARY ON USE OF DRUGS BY THE VA

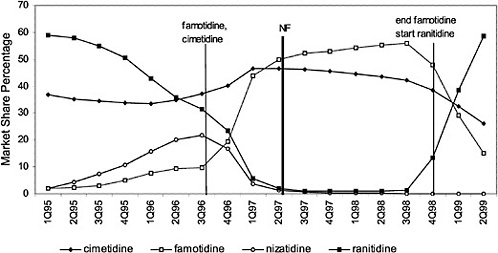

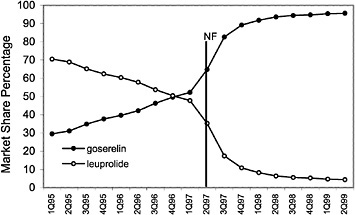

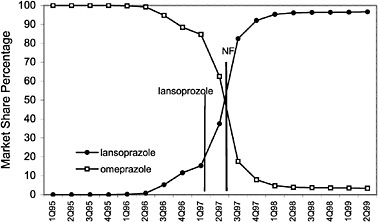

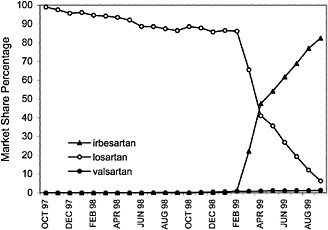

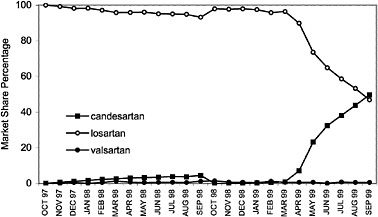

The committee evaluated the process of care by examining the number of prescriptions written for all drugs in closed and preferred classes from 1995 (prior to the National Formulary) until the second quarter of 1999. As expected, the selected drugs in closed classes were used significantly more than drugs not selected for the National Formulary. Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3 (PPIs and LHRHs) illustrate how a formulary drug achieves more than 90% volume and use of the nonformulary agent drops to near zero. Inclusion in a closed class on the National Formulary, however, is not the only significant driving force for drug utilization. In drug classes where more than one agent is on the National Formulary, national contracts or drug usage criteria are also associated with prescribing changes.

This occurs in all classes. Figure 4.4 shows the effects of a national contract for ranitidine. Increases or decreases in utilization follow the negotiation or termination of a contract. Termination of the contract for famotidine was associated with a marked decrease in utilization of this agent. At the same time, ranitidine utilization changed in association with the contract for this drug. Nonadherence reports typically show about 4 to 6% nonformulary use in closed classes, although the range is much wider. In open or preferred classes, noncontract use varies over time. VISNs and local facilities also have the prerogative of negotiating favorable prices through blanket purchase agreements and/or initiating programs to influence prescribing toward the least costly alternate in a class. Figure 4.5 and Figure 4.6 illustrate VISN programs to encourage use of different

FIGURE 4.2 National formulary policies affect market share of the luetinizing hormone-releasing hormone against drugs.

FIGURE 4.3 National formulary policies affect market share of the proton pump inhibitor drugs.

angiotensin II blockers for the treatment of high blood pressure, based on their assessments of cost and compliance factors. As illustrated, VISN 7 has shown a dramatic increase in the use of irbesartan with a decrease in the usage of losartan. Conversely, VISN 20 has shown an increase in the use of candesartan.

FIGURE 4.5 VISN policies affect the market share of the angiotensin2 (A2) antagonist drugs in VISN 7.

FIGURE 4.6 VISN policies affect angiontensin2 (A2) antagonist drug utilization for VISN 20.

If veterans travel to a different VISN where local or regional programs to encourage prescribing of particular members of a drug class are in force, they may experience quality problems unless interchange and nonformulary programs are responsive. These last two examples also demonstrate how local or VISN

decisions may differ among themselves and from National Formulary decisions. The committee did not find any scientifically valid evidence that the changes in the number or variety of drugs by class closure were affecting the quality of drug treatment and the health outcomes of veterans, however. To analyze such effects, patient-specific tracking of drug utilization would be needed.

ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS

In the final sections of this chapter, the committee discusses outcomes as quality indicators. The World Health Organization defines an adverse drug reaction (ADR) as an effect that is “noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy.” An adverse drug event (ADE) encompasses medical error, that is, “an injury caused by medical management rather than the underlying condition of the patient” (Institute of Medicine, 1999). Included are unintended effects of drugs or errors in the process of dispensing. Adverse consequences range from rash, headache, and diarrhea to organ failure or death. The end result is that ADRs or ADEs may result in both increases in health costs and decreases in quality of life.

Although adverse drug events can occur at any age, the elderly are particularly at risk, due in part to their higher per capita consumption of drugs and in part to their decreased physiologic capacity for drug handling or to comorbidities. Many health care organizations have made decreasing the risk of ADEs a high priority and have developed strategies to achieve this (ASHP, 1996; Institute of Medicine, 1999). Strategies include using computerized prescription entry; using machine-readable (bar) coding in their medication use process; developing better systems for reporting and monitoring ADEs; using unit dose medication distribution and pharmacy-based intravenous medication admixture systems; assigning pharmacists to work in patient care areas in collaboration with prescribers; seeking systems to prevent ADEs; and using pharmacists to actively review medication orders prior to dispensing.

The VA has devoted resources to decreasing ADEs. Four sites (VA Palo Alto, VA Cincinnati, VA New England White River Junction, and VA Tampa) have been awarded contracts to establish “Patient Safety Centers of Inquiry.” Two of these sites have a mission not only to collect information but also to implement systems to decrease errors. The New England center has been working with the Institute of Health Care Improvements to establish a breakthrough series to decrease ADEs. The programs are in their infancy and evaluations are not complete. The VA has completed switching to electronic prescribing, a system known to decrease errors. A program to implement machine-readable coding on all inpatient wards has been initiated and will presumably continue.

The main thrust of collecting and preventing ADEs in the VA is still at the local level. Few VISN formulary committees collect and discuss ADEs. VISN 2 and VISN 4 are part of the breakthrough series on ADEs. Another VISN (VISN 13) reports its ADEs during monthly teleconferences among facilities. Local facilities have employed different practices to decrease ADEs including programs such as

the breakthrough series. ADEs are reported to local P&T committees for review and action. In addition, many facilities commonly include pharmacists on the inpatient and outpatient wards, a procedure found to have a positive outcome in both VA and the private sector (Gray, 1992; Haig and Kiser, 1991). These pharmacists provide a variety of interactions, including suggestion of drugs and doses, monitoring of drugs with narrow therapeutic ratios, conducting chart reviews, and education of physicians and patients on aspects of drug therapy.

In theory, the VA Patient Safety Event Registry, initiated in 1997, could collect VHA national data on medication errors. The Registry did, in fact, report 171 medication errors (with 22 deaths) after the first 19 months of operation, varying from wrong dose, dispensing error, and wrong medication to “other.” The number of medication error reports was only 5.8% of the total events reported and varied 40-fold across VISNs. Some VISNs reported only one medication error during this period (Department of Veterans Affairs, 1999a). At present, the Registry does not appear to be a reliable source for identifying ADEs.

Although the VA National Formulary has introduced structural changes related to ADEs, other concurrent changes not resulting directly from the formulary (bar code recording, electronic prescribing, breakthrough series) confound a determination of formulary effects on ADEs. The committee did not find data on ADEs during therapeutic interchange, a specific element of the National Formulary. This is not surprising because reports to the FDA of ADEs associated with interchanges have also been infrequent from the health care system in general (FDA, 1997). The request for special reporting to the FDA presumably reflects this agency's interest in the consequences of therapeutic interchange. The FDA, however, has almost no data. Continued review of adverse event reporting has not resulted in reliable documentation of problems (P. Honig, FDA, personal communication, 2000). The system does not provide evidence of an association of poor health outcomes with interchanges; it only reports events, or anecdotes, with uncertain reliability.

Changes in Inpatient Hospital Discharges Associated with the National Formulary

In Chapter 3 of this report, the committee discusses gathering and analyzing new data on hospital discharges before and after the implementation of the National Formulary. These discharge data included discharges over 4 years for a group of diagnoses that might have been affected by changes in the availability of drugs used to treat them. These drugs were those known to be involved in restrictions by the National Formulary. The VA could not provide data on total pharmacy users, outpatient data for the relevant years, or patient-level drug data. These study years were also characterized by changes in hospitalization rates, movement to ambulatory care, and, undoubtedly, other confounding variables, including changes in medical practice and the clinical indications for the drugs involved. This analysis, therefore, is only suggestive that no major effects of the

TABLE 4.3 Most Frequent Formulary Complaints to Patient Advocates

|

3–4 Total Complaints |

5–10 Total Complaints |

>10 Total Complaints |

|

bicalutamide (Casodex) |

refecoxib (Vioxx) |

omeprazole (Prilosec; 15) |

|

Depens |

loratadine (Claritin) |

atorvastatin (Lipitor; 15) |

|

Alendronate (Fosamax) * |

troglitazone (Rezlin) |

celecoxib (Celebrex; 27) |

|

isosorbide (Imdur) |

tramadol (Ultram) |

sildenafil (Viagra; 60) |

|

interferon |

zolpiden (Ambien) |

|

|

amlodipine (Norvasc) |

alprostadil (Muse) |

|

|

ranitidine (Zantac) |

||

|

tolterodine (Detrol) * |

||

|

tamsulosin (Flomax) |

||

|

fluticasone (Flovent) |

||

|

famotidine (Pepcid) |

||

|

* The committee notes that these complaints were generated by female veterans who comprise only 4% of the veteran population. |

||

National Formulary and formulary system on health outcomes could be detected by this means (see Chapter 3 of this report).

PATIENT COMPLAINTS—ADVOCATE, VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS, AND SURVEY DATA

Patient complaints may suggest program areas where changes or improvements could be considered. Patient satisfaction is a generally accepted element of quality of care. Patient dissatisfaction discovered through significant levels of complaints to advocates or through surveys could be an important indicator of the need for a system response. The IOM contacted VA patient advocates at each facility for formulary-related complaints. Patient advocates did not code for formulary complaints prior to establishment of the VA National Formulary. Thus, data were available only from July 1997. Of course, some veteran dissatisfaction may not be expressed in complaints to patient advocates. Furthermore, not all visits to patient advocates are documented. The number of formulary-related complaints may be higher than reported, therefore.

Enough information was available to make some observations, however. Approximately 92% of all VA facilities representing all 22 VISNs responded to the committee's request for information. Nationally, only 2,385 of 570,937 complaints (0.4%) were attributed to the National Formulary. No VISN had significantly more complaints. The committee was able to identify the medications in question for 462 complaints. Not surprisingly, medications that are subject to direct-to-consumer marketing generated a number of complaints, as did lack of access to specific drugs that were considered desirable such as sildenafil (Viagra) (see Table 4.3). Since the collection of these data, the VA has developed clinical guidelines for the treatment of erectile dysfunction and criteria for the use of sildenafil. Most

complaints were from veterans unable to get a desired drug because it was not on the National Formulary or on VISN, or local formularies. In some other instances a local decision had been made not to stock a National Formulary drug or the local medical staff had decided to restrict it for medical reasons (H. M., Farrow, personal communication, VISN 16, 1999). Patient advocates interviewed agreed that the inability to obtain medications was not a major veteran complaint. Advocates near VISN regional borders received complaints about the availability of medications because of differences in VISN formularies. Overall, however, patient advocates heard few complaints concerning the National Formulary. The committee also contacted veteran groups for their formulary data to verify that formulary-related issues were not a major complaint among veterans. In 1997, the VFW established a toll-free complaint line as an additional advocate source for veterans. Nearly 20,000 complaints have been counted in 98 categories. Complaints concerning the formulary amounted to less than 0.2% of the total.

A large VA multicenter study of a therapeutic interchange program between HMG CoA RIs (switching fluvastatin to simvastatin) was carried out in 1999. In the course of this project, 3,153 surveys were mailed to patients, and 1,800 (57.1%) were returned. Although there were problems with the survey design and some confusion and incomplete responses from veterans, this study provided evidence of satisfaction with a National Formulary program based on adequate numbers and a reasonable response rate. An attempt was made to sort responses by whether veterans learned of the interchange by letter or were told by their pharmacist or physician. Among the former, 21–24% of veterans were neutral, that is, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, and 6 –8% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with how they learned of the exchange. Among the latter, similar results, 21% and 6–11%, respectively, were obtained. In 91–92% of responses, veterans believed the replacement medication was as effective as the original. About one-quarter to one-third of veterans reported that they received either no or inadequate information on the replacement medicine, however (W. N. Jones, personal communication, VISN 18, 1999).

Based on these data, the committee speculated that many veterans are aware (or are made aware through interchange notices) that there are budgetary restraints in the VHA and that some restrictions or cost-saving reactions are necessary. Most veterans seem to be tolerant of cost controls, although they could not be said to be enthusiastic, and some either complain or express their dissatisfaction when asked. As noted elsewhere in this report, there are potential improvements in VA programs that might address some concerns of these veterans. Overall, the committee did not find data on significant numbers of veterans expressing dissatisfaction with the National Formulary.

PHYSICIAN COMPLAINTS AND SURVEY DATA

Studies of physician satisfaction with formulary systems from the private sector and from the VHA specifically are reviewed in detail elsewhere. Insofar as physician dissatisfaction is a quality indicator, these studies are relevant here,

although they have sampling, numbers, and other design problems that weaken any conclusion that can be drawn from them. The data appear to identify a minority of VA physicians who have concerns about quality effects of the VA National Formulary and formulary system and are dissatisfied with the National Formulary (see Chapter 2 of this report). Most observers agree that physician compliance is essential to the success of a formulary and formulary system, and to that extent, dissatisfied, noncompliant physicians may impair the quality of the National Formulary. General surveys in the medical literature suggest that physicians do not automatically approve of formulary systems, especially those that practice therapeutic interchange. Navarro and Cahill (1999) have pointed out the natural antipathy that results when a professional (or indeed anyone) is faced with restrictions that prevent customary freedom and enforce cost-conscious behavior. These physicians need to feel a part of such formulary systems and to subscribe to formulary objectives.

The IOM committee is of the opinion, based on physician comments recorded in the Yankelovich Partners (1999) survey and others, that VA physicians by and large understand that the VHA has a fixed appropriation. They understand that overruns in one budgetary component obligate cutbacks in others. The discussions in this chapter raised the possibility that quality might be enhanced and physician acceptance of the National Formulary improved with some adjustments to the system. These included empowering physicians through more membership on influential committees involved with the National Formulary. Improvements in consistency and responsiveness of the nonformulary process should be implemented. Physician nonformulary performance could be examined retrospectively or through education. In a similar vein, one VA facility has given physician services target drug budgets for the year, and it reports expenditures and progress toward the target each month to each service. Although there is no penalty for exceeding the target, physicians are expected to support appeals for financing budget overruns. In principle, the involvement of practicing physicians in drug program management seems likely to help them understand the goals of the National Formulary.

SUMMARY STATEMENT

In this chapter, as its title indicates, the committee has explored the effects of the National Formulary and related policies on quality of care. Such an exploration inevitably questions whether there are quality effects sufficient and certain enough to support a decision to either abandon, continue, or strengthen the VA National Formulary. A completely firm and final answer to this question would require scientifically sound evidence of formulary influences on quality of care that affect process of care and health outcomes of veterans. However, there are no epidemiological or other well-designed studies of the VHA that conclusively provide such evidence one way or the other, that is, of either improvements or impairments in outcomes. The VA has apparently not completed any such studies or reported any such research. Some early and incomplete steps

in this direction have been taken, including some information in this report on hospital discharge distributions associated with the National Formulary. There are anecdotal reports of quality problems or successes, few veteran complaints, and some worrisome indicators of physician concerns. The absence of persuasive reports of substantial worsening of health outcomes in the medical literature attributable to a closed or partially closed formulary either for the VA or for millions of covered lives in MCOs or PBMs is not proof of no effect, although it is somewhat reassuring.

The committee fell back on, and relied primarily on a review of structural elements of the National Formulary related to quality. This review was also somewhat reassuring, including communications with, and reports of, an active and apparently skilled pharmacy service, observation of an active and thoughtful MAP, evidence of quality drug class reviews and a careful and rather parsimonious class closure process, reviews of therapeutic guidelines, an assessment that the formulary was of adequate size and quality, and an analysis of the formulary's effects on drug prices, with the implication that prudent drug purchasing freed funds for increased services to veterans.

Based on this information and analysis, the committee concluded that there is no reason to discontinue the National Formulary and every reason to try to improve it. In this latter regard, concerns are expressed in this chapter about the nonformulary process; the composition of committees; physician and patient satisfaction, therapeutic interchange policies, notice of interchanges, and education; follow-up and monitoring of clinical guidelines; and addition of newly FDA-approved drugs among others. The committee also strongly urges the VA to focus its considerable health services research capacity on National Formulary and drug treatment issues, in a way that hitherto has not been the case, as the responsibility of a national program to illuminate these issues. The absence of good data on quality effects is a concern, as is the need for better data to enable prudent management of the National Formulary. In the meantime, the committee supports the continuation of the National Formulary and formulary system. This includes the careful closure of classes where good therapeutic alternates exist and clinical and economic data are supportive, and an emphasis on quality of care for veterans as the highest priority.