3

Quality of Care and Quality Indicators for End-of-Life Cancer Care: Hope for the Best, Yet Prepare for the Worst

Joan M.Teno, M.D., M.S.

Brown University School of Medicine and Department of Community Health

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a life-defining illness. Half of those who get cancer die from it. Decades of research have resulted in cures for some forms of cancer, and for others, it is now a chronic, progressive, but still fatal illness. For those who die, quickly or after a long period of illness, health care providers must guide a patient through a disease trajectory where one must hope for the best, but prepare for the possibility of the worst. The management of this transition from hope for a cure to focus solely on comfort is key to quality end-of-life care. Important to this transition is medical care that is consistent with professional knowledge and that is based on informed patient preferences, to the extent the patient desires involvement in decisionmaking. The National Cancer Policy Board (NCPB) in its report Ensuring Quality Cancer Care (IOM, 1999) outlined a vision for the development of quality indicators to cover the spectrum of cancer care, including the dying process.

We are not close to meeting this NCPB mandate for care at the end of life, either for cancer or for other conditions. Research and demonstration programs will be needed before a preliminary set of satisfactory indicators can be developed. Ideally, such efforts should entail the collaboration of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR), and the National Institute on Aging (NIA). The focus of early work will be on the development and validation of measurement tools based on administrative data, medical records, and interviews with patients, family members,

and health care providers. These instruments must be developed and adapted for different cultures and ethnicities.

Measurement tools should be consistent with professional guidelines and the best available research. For many cancers, there is a strong evidence base to inform treatment decisions. However, research on the risks and benefits of cancer treatment, especially in those cases where chemotherapy, radiation treatment, and other treatment modalities are labeled palliative, is sorely lacking.

Ongoing national data collection efforts include little information to describe the quality of care of dying persons and their families. An occasional survey, the U.S. National Mortality Followback Survey (NMFBS), has collected information on access to care and functional status but not on important domains that are central to the quality of care of the dying. A redesigned NMFBS could collect information on key domains to describe the quality of care for cancer patients who died based on the perspective of the bereaved family member. Currently, there are no plans for further iterations of the NMFBS, however.

Quality indicators are needed for two main purposes: accountability (external use by regulators, health care purchasers, or consumers) and quality improvement (internal use for the purpose of monitoring or continuous quality improvement). The same types of indicators may serve both purposes, but the indicators may also be different. At this early stage in development, there is a strong evidence base to support the development of quality indicators for pain management for the purpose of accountability. However, demonstration programs will be needed before pain management indicators can be implemented nationally, and more basic research is needed to develop indicators for managing other common symptoms (e.g., emotional distress and depression, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms). An important aspect of demonstration and validation is monitoring for potential unintended consequences (e.g., patients are sedated contrary to their preferences to improve accountability statistics).

Besides the domain of symptom management, four other domains should be considered for early development and implementation of accountability measures: (1) patient satisfaction, (2) shared decisionmaking, (3) coordination, and (4) continuity of care. In each of these domains, indicators must validly represent the perceptions of the dying person and family members. This means investing in new survey methods that are patient centered and include questions that get at unmet needs, which has not always been the norm.

Shared decisionmaking has been increasingly recognized as a key aspect throughout the continuum of care. While the focus of research has been on resuscitation decisions, the most important decision for the majority of

cancer patients is the one to stop active treatment, but there is little research examining this decision.

There is strong support for the domains of pain (and other symptoms), shared decisionmaking, satisfaction, coordination, and continuity of care, but there is debate about which other domains are important in the care of the dying. Various conceptual models have been proposed to examine the quality of end-of-life care, emphasizing different domains. Research is now needed to examine the correlations among structures of the health care system, processes of care, and important outcomes to identify the most fruitful areas for developing new quality measures.

Two national data collection systems warrant consideration for the development of quality indicators: Medicare claims files and the Minimum Data Set (MDS). NCPB has recommended that hospice enrollment and length of stay be examined as quality indicators (IOM, 1999) From a national perspective, the only data set with that information is Medicare claims data. Other indicators based on administrative data have also been proposed (Wennberg, 1998). Work to develop and validate these indicators using claims data is still to be done.

The second national data collection effort is the MDS, which routinely collects extensive information on every nursing home resident in the United States. Nursing homes increasingly are providing end-of-life care for frail and older Americans (Teno, 2000a). In 1998, an estimated 10 percent of cancer patients died in a nursing home. The Health Care Financing Agency (HCFA) is now embarking on a national program of examining nursing home quality performance. There are important lessons to be learned from the MDS, including concerns about the institutional response burden in implementing data collection and the potential for unintended consequences. In the nursing home setting, the main concern is with applying quality indicators developed for populations where the goals of care are on restoring function to those who are dying. For example, the rates of dehydration and weight loss are now among the core quality indicators for nursing homes (HCFA, 2000). With increased scrutiny of these indicators, there is concern that unintended consequences for the dying include increased use of feeding tubes, which could be contrary to patient preferences.

At this time, health care providers usually apply the term “dying” to individuals in the last days of life, allowing little time for preparation or life closure. Given the inherent imprecision of predicting the day of death, we need to move back on the continuum and identify people with “life-limiting illness” or “serious, progressive illness,” which would imply a median survival of less than one year.

“Hope for the best, prepare for the worst” is not something we say to people dying of cancer. In one sense, it forces us to admit failure to a disease

that is the second leading cause of death in the United States. While it is the disease that we are “fighting,” our ultimate obligation is to provide the best-quality care to each individual patient, and we must recognize that individual preferences are central to defining the quality of medical care. Health care providers must not only provide the best available clinical care, as desired by patients, but must become adept at helping patients and families make choices about transitions in goals of care. The goal of quality indicators is to measure the extent to which the health care system is succeeding in this at the end of life.

QUALITY OF END-OF-LIFE CANCER CARE

Few, if any, would argue seriously against the current emphasis on prevention and cure in cancer research and treatment. Yet this emphasis should not be allowed to result in inadequate care of the half-million people who die from cancer each year in the United States, whose final needs are for treating symptoms as they approach death. The National Cancer Policy Board, in Ensuring Quality Cancer Care (IOM, 1999), noted the wide disparity between the “ideal” cancer care system and the reality that confronts people with cancer today. The gaps are nowhere as large as they are in the realm of care for the dying.

A central premise of this chapter is that patient expectations and preferences are fundamental to defining the quality of medical care for people with chronic, progressive, and eventually fatal illnesses. Fundamental to any discussion of quality of care, however, are measures of quality that are valid and reliable. This chapter focuses on the status of “quality indicators” for assessing the care of dying individuals, particularly those dying from cancer.

Dying is unlike any other time in a person’s life. A 41-year-old with his first heart attack will most likely value the same health outcomes as others with the same diagnosis: a focus on minimizing the extent of damage to the heart, preserving cardiac function, and reducing the risk of another heart attack. Those dying from chronic, progressive, and eventually fatal illnesses, however, may choose very different courses. The goals of care for a dying person cannot reasonably be anticipated, as they can in the case of a heart attack patient. To care well for a dying person, health care providers must understand that person, his or her needs and expectations, and the disease trajectory itself.

Care of the dying is distinct from other aspects of health care in that it is delivered not just to the patient, but in the context of a “family” (in its most inclusive definition, not restricted to the legal definition of “family”) (WHO, 1990). Ideally, care is “patient focused,” which is defined as care

that promotes informed patient involvement in decisionmaking and attends to physical comfort and emotional support.

In the past century, the United States has seen a striking transformation in how people die. In contrast to the late 1800s, people now die of chronic, progressive, and eventually fatal illness such as cancer, which they may live with for years or decades. Faced with caring for an older and chronically ill population, public policy and research efforts have focused on examining not only survival but also quality of life and health care costs.

In a New England Journal of Medicine editorial, accountability was identified as the “third revolution in medical care,” following on the heels of health care expansion and cost containment (Relman, 1988). Yet, to date, little attention has been given to how best we can measure the quality of end-of-life care. Despite the universality of death, few generalizable research studies (Addington Hall and McCarthy, 1995; Emanuel et al., 2000; Greer et al., 1986; Lynn et al., 1997; Seale et al., 1997; Wolfe et al., 2000) have examined the experiences of dying persons. At this early stage, cancer represents an ideal disease trajectory on which to initiate work measuring quality of care of the dying for the purposes of accountability (i.e., external release of data to the purchaser, regulator, or consumer in order to compare and contrast quality between health care institutions), quality improvement, and research.

Cancer, in contrast to other leading causes of death (e.g., congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, stroke), has a more predictable functional trajectory prior to death with less uncertainty in prognosis (Fox et al., 1999; Teno et al., 2001). Some cancers have an authoritative scientific evidence base to guide treatment decisions. Health care providers now have access to evidence-based treatment algorithms, including some for palliative treatment (ASCO, 1997). For these reasons, cancer is a good place to start designing and implementing a national system to measure the quality of end-of-life care.

What Is an Ideal System for Monitoring Quality of Care for Cancer?

The NCPB has outlined the characteristics of an ideal system for measuring quality of care for cancer patients. In order to meet these goals, we will need appropriate measurement tools for research to develop the scientific evidence base, for quality improvement, and for public accountability (Table 3-1), all of which may be different.

The areas of emphasis and desired characteristics vary for measurement tools intended for different purposes (Table 3-2). For example, the intended audience for quality improvement (QI) measures is the institutional and QI staff, whereas the intended audience for public accountability is the health care purchaser and consumer. Given the intended audiences and implica-

TABLE 3-1 Purposes of Quality Measures

|

Purpose |

Description |

|

Quality improvement |

Measures to provide information for health care institutions to reform or shape how care is provided |

|

Clinical assessment |

Measures to guide individual patient management |

|

Research |

Measures that assess the phenomenon of interest |

|

Accountability |

Measures that allow comparison of quality of care for the purposes of quality assurance or for consumer choice between health care institutions or practitioners |

|

SOURCE: Teno et al., 1999. |

|

TABLE 3-2 Areas of Emphasis Based on the Purpose of Quality Measure

|

|

Purpose of Measure |

|||

|

|

Clinical Assessment |

Research |

Improvement |

Accountability |

|

Audience |

Clinical staff |

Science community |

QI team and clinical staff |

Payers, public |

|

Focus of measurement |

Status of patient |

Knowledge |

Understand care process |

Comparison |

|

Confidentiality |

Very high |

Very high |

Very high |

Low |

|

Evidence base to justify use of measure |

Important; measure should have face validity from a clinical standpoint |

Builds on existing evidence to generate new knowledge |

Important |

Extremely important in that proposed domain ought to be under control of the institution |

|

Importance of psychometric properties |

Important to individual provider |

Extremely important to the research effort |

Important within specific setting |

Valid and responsive across multiple settings |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Solberg et al. (1997) and Teno et al. (1999). |

||||

tions of the use of measurement tools, more stringent psychometric properties than are now employed must be put into measures that will be used for public accountability. In addition, there must be either normative or empirical research substantiating a claim that the construct being measured for public accountability is under the control of the health care institution.

It seems easy to conceptualize quality measures for various purposes, but in practice, we are at an early stage in measuring the quality of end-of-life care. Substantial normative and empirical research is still needed to develop and validate a conceptual model of quality end-of-life care, to develop and test the psychometric properties of proposed measurement tools, and to demonstrate the tools’ effectiveness in multisite studies before they can be used nationally. This chapter describes what is known and what still needs to be done to develop widely applicable quality indicators for end-of-life care for cancer patients. The following questions guide the discussion:

-

What is currently known about the quality of care for dying cancer patients?

-

What are the proposed definitions and conceptual models for quality of care of dying persons and their family?

-

What can we currently measure with existing nationally collected data?

-

What do we want to be able to say in the future?

-

What research is needed?

What Is Currently Known About Quality of Care of the Dying Cancer Patient?

Few studies have characterized the experience for dying cancer patients and their families. From a national perspective, only one ongoing data collection effort routinely characterizes dying from cancer, and a second occasional survey was carried out six times between the early 1960s and 1993. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) compiles data from all death certificates nationwide and publishes annual summaries that include cause of death, place of death, and other demographic information.

The other survey that has characterized aspects of dying is the NMFBS, last carried out in 1993. The 1993 survey represents a 1 percent sample of all deaths at age 15 and older. Unlike the mortality followback surveys in the United Kingdom (Addington Hall and McCarthy, 1995a, 1995b), the NMFBS does not characterize the quality of the dying experience (e.g., pain management, satisfaction). Rather, the U.S. survey collects information on socio-demographics, use of alcohol and medications, lifestyle, health care resource utilization, and difficulties with functioning (Lentzner et al., 1992; NCHS, 1998).

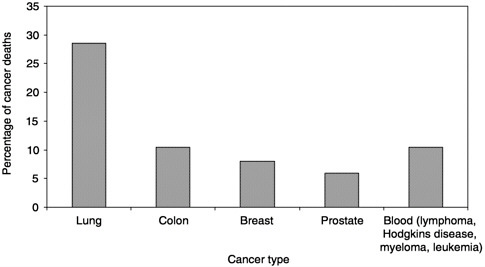

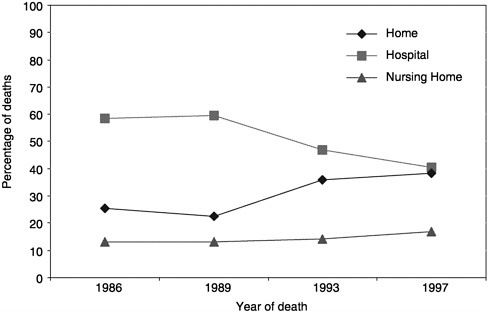

What can be learned from the available data? In 1998, 538,947 people died of cancer in the United States. Five types of cancer account for 70 percent of those deaths (Figure 3-1; NCHS Web site). Over the past decade, there has been a trend toward more cancer patients dying at home (Figure 3-2;

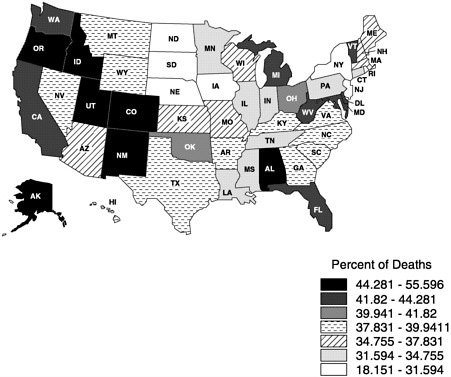

mortality files and NMFBS). There is, however, substantial geographic variation in the site of death (Figure 3-3) (Pritchard et al., 1998; Wennberg, 1998). For example, Oregon has experienced a dramatic increase in the proportion of people dying at home (probably due to a number of factors, including closing of hospital beds and a vigorous public debate about physician aid in dying) (Tolle et al., 1999).

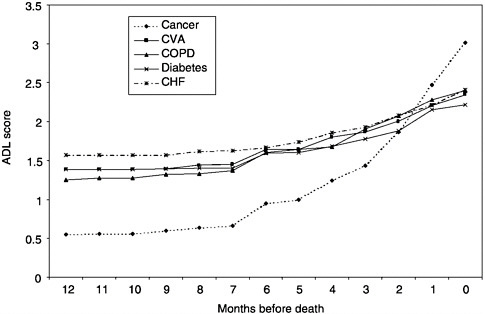

Based on the 1993 NMFBS, cancer patients are less likely to be functionally impaired in the last year of life and experience a more precipitous functional decline in the last five months of life than those dying from other causes (Figure 3-4), as measured by difficulty with activities of daily living (ADL: bathing, dressing, eating, transferring from a bed or chair, and using the toilet). In that year, nearly half of these deaths occurred in an acute care hospital, and 36 percent, at home. Only 19.7 percent of those who died from cancer in 1993 used hospice care. The functional trajectory measured as the number of ADL impairments in the last five months of life was associated with dying at home and with hospice involvement (Teno et al., 2001).

FIGURE 3-3 Proportion of cancer home deaths in 1997. Copyright, Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, used by permission.

FIGURE 3-4 Age-adjusted ADL scores by time before death.

NOTE: ADL=activities of daily living; CHF=congestive heart failure, COPD= chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA=cardiovascular accident (stroke).

In Ensuring Quality Cancer Care (IOM, 1999), the NCPB recommended ensuring timely referral of dying cancer patients to palliative and hospice care. Currently, the only data that can shed light on the timing of these referrals are from Medicare claims files, and these do not tell the story of whether referrals are “timely.” However, they do demonstrate a dramatic reduction in the median length of hospice stay during the late 1990s and substantial geographic variation in length of stay. In 1990, reported median length of stay was 36 days (Christakis and Escarce, 1996). According to the National Hospice Organization (NHO), this had declined to 25 days by 1998. There has been some speculation that the decline is due, in part, to efforts to avoid charges of Medicare fraud, which may cause practitioners and hospice providers to delay enrolling patients until they are very close to death.

Information on access to medical care was collected in the 1986 and 1993 NMFBS. In 1993, the question asked was, Were there any times during the last year of life that…needed health care, but didn’t get it? Eleven percent of respondents stated that they had difficulty obtaining needed care, which seems relatively small. However, this question should be repeated in future surveys, because access to care is continually changing.

While the NMFBS has provided some information about the dying experience, health care providers cannot answer the important question, What will my dying be like? Information about the bereaved family member’s perspective on the quality of care, concerns about pain management, or whether medical care was in accord with the patient’s informed preferences is not included. To address these issues, we must rely on less generalizable studies.

Future Directions:

Funding a seventh wave of the National Mortality Followback Survey should be considered. If carried out, it should include data collection to document a surrogate perspective on quality of care with a focus on issues that proxies are known to report accurately—access to care, decisionmaking, advance care planning, coordination of care, and the financial impact on dying persons and families.

Additional research should be conducted to improve the quality of followback reporting (e.g., to examine the best timing of interviews within the constraints of current reporting of death data). Research is also needed to examine the types of people best able to serve as proxies, what they are able to validly report on, the impact of bereavement, and the validity of interviews with family members.

Pain

Pain is common among people dying from cancer. Severe pain may signify that death is not far off (Conill et al., 1997; Foley, 1979; Portenoy et al., 1994a; Turner et al., 1996). Cancer pain, itself, can lead to anxiety, depression, and even suicide (Spiegel et al., 1994; Strang, 1992). One study found that requests for physician aid in dying were withdrawn once the patient was appropriately treated for pain (Foley, 1991). The general public is fearful that the discomfort associated with cancer will be “extremely painful” (Levin et al., 1985). Nearly 70 percent of people believe cancer pain can be so severe that a patient considers suicide. Are such concerns warranted?

Multicenter studies in hospitals (Desbiens et al., 1996; SUPPORT Principal Investigators, 1996), outpatient settings (Cleeland et al., 1994), and nursing homes attest to important public health concern with pain assessment and management (Bernabei et al., 1998). In the Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT), 22.7 percent of patients reported moderately or extremely severe pain at least half the time during their first week of hospitalization. Bereaved family members reported that more than 40 percent of those who

died of colon or lung cancer had severe pain in the last three days of life. Despite this level of pain, family members reported satisfaction with pain control, which seems to reflect relatively low expectations.

Among 54 outpatient clinics participating in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), about one-third of patients with metastatic cancer had pain that limited their function. Of the two-thirds of patients with pain, 42 percent reported that their pain was not adequately treated (Cleeland et al., 1994). Supporting these patient reports, 86 percent of ECOG physicians stated that pain was undermedicated. In a study of nursing homes in five states, 40 percent of patients discharged with a diagnosis of cancer had daily pain (Bernabei et al., 1998). Of even greater concern, one in four of these patients was not receiving any pain medication—not even a World Health Organization (WHO) step 1 drug, such as acetaminophen.

Even in a hospice or palliative care setting, pain remains an important concern (Higginson and McCarthy, 1989; Hockley et al., 1988; Morris, Mor et al., 1986; Turner et al., 1996; Vainio and Auvinen, 1996). Although pain may always be ameliorated by sedation with barbiturates as a last resort (Truog et al., 1992), significant controversy exists over the rate at which a dying cancer patient’s suffering requires deep sedation. Ventafridda and colleagues found that more than half of the dying people treated through a home care program in Italy could achieve palliation of suffering only by sedation (Ventafridda et al., 1986; 1989). Must they sleep before they die? asked an editorial, questioning whether this represents overtreatment (Roy, 1990). A study of dying patients in a palliative care unit in Canada found that only 16 percent of patients required sedation for symptom relief (Fainsinger et al., 1991).

In summary, there is strong evidence that pain is prevalent and too often untreated, despite clear, appropriate guidelines. If guidelines were followed, pain could be ameliorated for up to 90 percent of patients. Because of the high prevalence of pain and because it can be alleviated with proper treatment, pain and its control should be an outcome measure used to judge the quality of end-of-life care for purposes of public accountability.

Future Directions:

The NCI, AHRQ, Department of Defense, and Department of Veterans Affairs could consider research and demonstration efforts to implement accountability measures for pain management. In these efforts, the potential unintended consequences of measuring pain management (e.g., more persons being sedated without informed discussion) should be monitored. If warranted by the results, HCFA could require monitoring of pain management as part on ongoing quality reporting from health care institutions that participate in Medicare.

Dyspnea and Other Symptoms

Patients, family members, and health care providers report that dyspnea is one of the most burdensome and difficult symptoms to treat in the last days of life (Dudgeon and Rosenthal, 1996; Farncombe, 1997; Hockley et al., 1988; Kuebler, 1996; Nelson and Walsh, 1991; Ripamonti and Bruera, 1997; van der Molen, 1995). Between 21 percent and 89 percent of dying people report directly (Donnelly and Walsh, 1995; Dudgeon et al., 1995; Hay et al., 1996; Hopwood and Stephens, 1995; Portenoy et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 1993; Vainio and Auvinen, 1996) or are observed to have difficulty breathing in the final phase of life (Addington Hall and McCarthy, 1995b; Coyle et al., 1990; Desbiens et al., 1997; Edmonds et al., 2000; Fainsinger et al., 1991; Goodlin et al., 1998; Higginson and McCarthy, 1989; Hockley et al., 1988; Lynn et al., 1997; Marin et al., 1987; Muers and Round, 1993; Reuben and Mor, 1986; Robinson et al., 1997. Similar to worsening pain, increasing dyspnea implies a shorter survival time. Half of all lung cancer patients presenting to an emergency room with dyspnea die in the following month (Escalante et al., 1996).

Research has shown that unlike pain, dyspnea persists as a troublesome symptom even in patients receiving palliative care. Both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions are limited (Higginson and McCarthy, 1989; Ripamonti, 1999) (although a recent trial suggests an important role of nonpharmacological interventions using relaxation techniques; Breitbart et al., 1995). This is not unexpected, because for many cancer patients, lung tissue is replaced with nonfunctional tumor tissue such that the patient follows the clinical course of a person with restrictive lung disease.

In addition to the distressing symptoms of pain and dyspnea, cancer patients often endure a constellation of other symptoms. More than 90 percent of people with advanced cancer who are close to death have more than three distressing symptoms (Donnelly and Walsh, 1995). Weakness afflicts between 51 percent and 88 percent of dying cancer patients, and at least one-quarter have one or more gastrointestinal symptom, including nausea, vomiting, and anorexia (Conill et al., 1997; Donnelly and Walsh, 1995; Hockley et al., 1988; Portenoy et al., 1994b; Turner et al., 1996; Vainio and Auvinen, 1996). Confusion, which is often devastating to family members, is found in between 8 percent and 85 percent of dying cancer patients (Breitbart et al., 1995; Conill et al., 1997; Donnelly and Walsh, 1995; Hockley et al., 1988; Turner et al., 1996; Vainio and Auvinen, 1996).

With the exception of pain, interventions for managing these symptoms are not well characterized and the tools themselves are probably inadequate. In addition, there are disagreements among professionals about

appropriate treatment. The use of intravenous fluids, for example, is often viewed as not the “hospice way” to care for actively dying patients. The argument is that it is a natural part of the dying process for persons to decrease their intake of fluids and that symptoms attributable to dehydration can be managed by ice chips and aggressive mouth care (McCann et al., 1994). However, others suggest that hydration through subcutaneous saline injection can ameliorate or reverse agitation in dying persons (Fainsinger and Bruera, 1997).

Despite reports of striking levels of patient distress, reliable and valid tools to measure symptoms are often lacking. For example, many dying persons are unable to report either their pain or discomfort from dyspnea. It will be difficult to document progress unless the necessary tools are developed.

Future Directions:

The scientific evidence base of, and current measurement tools for physical symptoms other than pain need further refinement prior to their use for public accountability. For physical symptoms other than pain, existing measures have to be refined, new measurement tools must be developed, research on treatment effectiveness has to be conducted, and guidelines must be formulated. NCI, in collaboration with other federal research agencies, could take the lead in developing this scientific evidence base for the palliation of physical symptoms of persons dying from cancer.

Emotional Distress

Emotional distress greatly diminishes the quality of life of dying patients and their families. Depression and anxiety inhibit the patient’s ability to experience pleasure and to focus on the conclusion of significant relationships (Block, 2000) and may impair the ability to make critical decisions. From a clinical standpoint, health care workers should recognize and treat emotional distress to enable the patient and family to participate fully in end-of-life decisionmaking and attain a sense of closure in the time remaining before death.

Depression and anxiety, as well as an increased risk of suicide, among patients with cancer and other terminal illnesses have been documented for two decades, but the reported prevalences vary widely, depending on diagnostic criteria and study design (DeFlorio and Massie, 1995). Using a self-report measure of common symptoms, 65 percent of patients with breast, colon, prostate, or ovarian cancer reported feeling sad, and 61 percent reported feeling nervous (Portenoy et al., 1994a). In a study limited to those with advanced cancer, 21 percent of patients reported moderate or severe

depression, and 13 percent of women and 9 percent of men reported moderate or severe anxiety (Donnelly et al., 1995). Using the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Revised Edition (DSM-IIIR) diagnostic criteria adapted for terminally ill patients, 26 percent of terminally ill cancer patients met the criteria for depression (Power et al., 1993).

Thoughts of suicide among terminally ill patients are relatively common (Block, 2000). In a sample of patients with terminal cancer in palliative care hospital units for example, 44.5 percent acknowledged occasional desires for death (Chochinov et al., 1995). Even though the majority of suicidal thoughts among patients with terminal illnesses are transient, the reported suicide rate among patients with cancer is twice that of the general population, with the greatest risk during advanced illness. Moreover, the actual suicide rate among cancer patients may be underestimated since some family members may be unwilling to report that a terminally ill cancer patient died as a result of suicide (Chochinov et al., 1998). Despite the wide variation in reported rates of emotional distress and the difficulty of assessing the true suicide risk among patients with cancer, it is clear that depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation affect a large enough portion of cancer patients to warrant further research regarding their measurement and the efficacy of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments (e.g., individual or group therapy) that can help patients come to terms with impending death (Block, 2000; Spiegel et al., 1994).

Although there is no consensus regarding the best or most useful tool for diagnosing emotional distress among terminally ill cancer patients, two broad categories of assessment tools have been employed: self-report questionnaires and clinical interview diagnostic criteria. Researchers have used many self-report questionnaires measuring psychological well-being to assess emotional distress among cancer patients; however, only the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (Portenoy, et al., 1994b) was designed specifically to measure symptoms common to cancer. Similarly, although standard clinical diagnostic criteria (e.g., the DSM series) are widely used in the general population, versions modified for people with medical illness have to be validated (Kathol et al., 1990), and tools geared toward palliative care that are sensitive to cultural and ethnic differences must be developed (Breitbart et al., 1995; Lewis-Fernandez and Kleinman, 1995).

Future Directions:

NCI could fund development of measures, descriptive studies, and research on treatment for anxiety and depression among cancer patients diagnosed as having a life-limiting condition.

Shared Decisionmaking

With the development of more effective treatments, cancer has become curable for some, and for others, a chronic, progressive illness that people live with and, with their health care providers, manage over time. One consequence of this change is that physicians and patients must communicate with each other in ways that previously were unimportant. Communication research has focused largely on decisionmaking at the end of life, in particular, on the single issue of a “do-not-resuscitate” (DNR) decision. As important as that is, even more important for many patients is a decision to stop chemotherapy or other active treatment, but this decision has yet to be fully studied.

Patient preferences have an important role in shared medical decision-making. Published guidelines regarding end-of-life care strongly endorse a patient’s right to participate in health care decisions (Teno et al., 2001a). For example, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) calls for physicians to speak truthfully to cancer patients and families about prognosis, treatment options, and advance care planning (ASCO, 1998). Despite widespread endorsement by professional guidelines, the Patient Self-Determination Act, and court rulings, there is still significant concern about whether patients’ preferences are honored along with persistent claims that they are “trumped” by physicians. The evidence to support this claim is scant and derives in large part from misinterpretations of SUPPORT results and studies that asked for the perceptions of nurses and physicians in training (e.g., a report that one in two health care providers believe they had provided overly aggressive medical care to a dying person) (Solomon et al., 1993).

The SUPPORT results were widely reported and have had a lasting impact that does not necessarily represent their most accurate interpretation. US News and World Report headlines were, “Doctors Don’t Listen” and “…Doctors Don’t Talk About Bad News” —the implication being that physicians were ignoring individuals’ informed preferences. Half of the patients in SUPPORT with colon cancer who voiced a preference to avoid resuscitation did not have a DNR order (Haidet et al., 1998), but even so, these patients were not resuscitated against their preferences (Hakim et al., 1996). Similarly, a review of those deaths with an advance directive found only one case in which an advance directive was trumped at the request of the family (not by a physician) (Teno et al., 1998). Whether it was ethically defensible to delay the death of this unconscious patient so that his daughter could come to grips with the decision can be debated.

The larger area of concern is not that patient preferences are being ignored but rather questions regarding the timing of communication and interpretation of the intended meaning of “hopelessly ill.” In a qualitative

study of advance directives in SUPPORT, Teno and colleagues (1998) found that advance directives were invoked and often played a role in decision making. However, directives were invoked only when the patient was “hopelessly ill.”

Moving this decision upstream from a point when treatment is judged almost certainly futile will take a fundamental change in the dialogue that occurs between patients, families, and physicians. Discussion of prognosis at an earlier stage must be accomplished in such a way that it does not shatter hope, yet allows a dying person to make realistic choices about medical care. Cancer, unlike other leading causes of death, does have a relatively predictable disease trajectory that would allow for such dialogues to be developed and implemented.

The lack of impact of the SUPPORT intervention (which provided physicians with information on patient preferences and prognoses but did not result in increased physician understanding of patient preferences, timing of DNR orders, reduction in days spent in undesirable outcome states, and reduction in resource utilization) has been taken by some as a rationale for endorsing “glide paths” (i.e., “default pathways”), rather than finding better ways to communicate and, ultimately, implement patient self-determination. A careful review of the SUPPORT findings, however, suggests that the intervention itself was inadequate to improve communication, not that improved communication is impossible.

Given the existing research, the only firm conclusion that can be drawn is that communication is lacking between physicians and patients (Haidet et al., 1998; SUPPORT Principal Investigators, 1996) and that physicians often misunderstand patient preferences (Teno et al., 1995). Research in communication and decisionmaking has focused largely on the last days of life. The more sentinel decisions, though, may be stopping active treatment or choosing palliative chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgical treatment earlier in the course of illness. The evidence base to support guidelines for these decisions is preliminary at best. Research on how best to communicate this information to patients has only begun.

Future Directions:

NCI and AHRQ could fund research to develop the evidence base for palliative chemotherapy, radiation, and other treatment modalities. Such research should consider the treatment’s meaning to patients and families, toxicity, and impact on quality of life.

Cooperative Oncology Groups could standardize measures and schedules to examine both treatment toxicity and quality of life. This would facilitate meta-analyses to develop the evidence base for palliative chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical treatments.

NCI could sponsor research with the NIA and AHRQ to study communication of information about risks and burdens of chemotherapy in making treatment decisions with persons whose cancer is expected to be fatal. Consideration could be given to funding a center of excellence in communication regarding end-of-life care. Such a center would address issues such as stopping active cancer treatment and the use of chemotherapy, radiation, and other modalities for palliative intent only.

ASCO and other professional organizations could develop clinical guidelines regarding the point at which physicians should discuss the burdens and benefits of continued chemotherapy, including the presentation of information about hospice and/or palliative care.

Decisions regarding treatment approaches in cancer require consideration of the trade-offs of quality versus quantity of life. With increasing use of capitation, the incentive may be to provide less care. Measurement tools that examine whether treatment decisions reflect informed patient preferences should be developed and validated. Such measures, if validated, could be incorporated into HCFA’s ongoing effort to monitor the quality of managed care.

Proposed Definitions and Conceptual Models of Quality of Care

Dying is a time unlike any other, and more than at any other time, patients’ preferences are central to defining the quality of care. While one patient may choose an experimental chemotherapeutic trial and even continued intravenous (IV) hydration in an inpatient hospice unit, another patient with the same diagnosis may choose aggressive treatment with IV opiates for distress from dyspnea but no chemotherapy. Essential to the quality of care for a cancer patient is meeting the patient’s needs and expectations within society’s imposed constraints.

A previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) report defined quality of care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increased the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990). This definition implies that conceptual models for quality of care (as well as instruments measuring quality) must be based on both professional knowledge (based on scientific evidence) and informed patient preferences. Most conceptual models have been built either around expert opinion (Emanuel and Emanuel, 1998; IOM, 1997; Lynn, 1997; NHO, 1997; Stewart et al., 1999) or on qualitative data from patients, families, or health care providers Singer et al., 1999; Steinhauser et al., 2000; Teno et al., in preparation). Only one proposed model incorporates both the expert and the consumer perspectives (Table 3-3).

TABLE 3-3 Comparison of Domains of Experts, Patients, Family Members, Health Care Providers, and New Proposed Model

|

Expert Opinion |

Consumer Opinion |

||

|

Emanuel and Emanuel (1998) |

IOM (1990) |

NHO Pathway (1997) |

Patients with HIV, Renal Failure on Dialysis, and Nursing Home Residents (Seale et al., 1997) |

|

Physical symptoms |

Overall quality of life |

Safe and comfortable dying |

Receiving adequate pain and symptom management |

|

Psychological and cognitive symptoms |

Physical well-being and functioning |

Self-determined life closure |

Avoiding inappropriate prolongation of the dying |

|

Social relationships and support |

Psychosocial well-being and functioning |

Effective grieving |

Achieving sense of control |

|

Economic demands and caregiving demands |

Family well-being and perceptions |

|

Relieving burdens |

|

Hopes and expectations |

|

|

Strengthening relationships |

|

Spiritual and existential beliefs |

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: Based on Teno et al., 2001. |

|||

Experts and consumers agree in many ways about what is important to end-of-life care—physical comfort, emotional support, and autonomy—but they have significant areas of disagreement, as well (e.g., on unmet needs; Table 3-3). Family members want more information on what to expect and how they can help their dying loved ones. Patients and families emphasize the importance of closure at the end of life, including issues of personal relationships. Families often speak of frustration with the lack of coordination of medical care. It often isn’t clear who was in charge, different health

|

|

Combined Model |

|

|

Patients, Families, and Health Care Providers |

Bereaved Family Members from the Current Study |

New Proposed Conceptual Model of Patient-Focused, Family-Centered Medical Care |

|

Pain and symptom management |

Providing desired physical comfort |

Provide desired level of physical comfort and emotional support |

|

Clear decisionmaking |

Achieving control over health care decisions and everyday decisions |

Promote shared decisionmaking |

|

Preparation for death |

Burden of advocating for quality medical care |

Focus on the individual. This includes closure, respect, and patient dignity. |

|

Completion |

Educating on what to expect, and increasing confidence in providing care |

Attend to the needs of the family for information, increasing their confidence in helping with patient care and providing emotional support prior to and after the patient’s death. |

|

Contributing to others |

Emotional support prior to and after the patient’s death |

Coordination and continuity of care |

|

Affirmation of the whole person |

|

Informing and educating |

care providers provide conflicting information, and transitions can be fraught with confusion.

Teno and colleagues’ (2001) model of patient-focused, family-centered medical care (Table 3-3) is based on a review of existing professional guidelines and focus groups conducted with family members. For the seriously ill patient, institutions and care providers striving to achieve patient-focused, family-centered medical care should

-

provide the desired level of physical comfort and emotional support;

-

promote shared decisionmaking, including advance care planning;

-

focus on the individual patient by facilitating situations in which patients achieve their desired level of control, staff members treat patients with respect and dignity, and patients are aided in achieving their desired levels of closure; and

-

attend to the needs of caregivers for information and skills in providing care for the patient, and provide emotional support to the family before and after the patient’s death.

In the ideal quality-monitoring system for cancer, guidelines and proposed quality indicators should be strongly linked. Guidelines should be based on both normative and empirical research. A quality indicator can measure information about the structure of the health care institution (e.g., availability of certain services, existence of policies), processes (i.e., interactions of health care providers, patients, and family), and outcomes (i.e., effectiveness of treatment). Currently, most quality indicators measure either structure or processes of care. Outcome measures are intuitively more attractive, but they are more difficult to apply because of our limited ability to adjust for differences in patient characteristics and the relatively small numbers of people with a particular condition treated at institutions each year (Brook et al., 1996). One argument in favor of process data is that they are a more sensitive measure of quality because adverse outcomes do not occur every time there is an error in the provision of medical care (Brook et al., 1996). Also, important outcomes—both positive and negative—often appear months or even years after care has been given. Quality indicators based on measures of structure or process, however, are only as good as their predictiveness for outcomes of importance.

Future Directions:

NCI and AHRQ could fund research to elucidate the interrelations of structure, process, and outcomes of care, in order to develop valid quality indicators.

Surveys and chart abstraction tools have been designed to examine the quality of care of the dying for purposes of quality improvement and research. SUPPORT used both chart abstraction tools (examining reported patient involvement in decisions and the point at which a decision was made) and interviews with patients and family members. Other tools have been developed that examine the documentation regarding pain management (Weissman et al., 2000).

SUPPORT demonstrated that a majority of seriously ill patients cannot be interviewed (Wenger et al., 1994). As a result, the research choice be-

comes either to eliminate those cases or to rely on information given by a surrogate, usually a family member. The tools developed for SUPPORT reflect survey methodologies of the early 1980s, which had important limitations—including lowered patient expectations and subsequent high satisfaction with the quality of care. For example, Desbiens and colleagues (1996) reported that persons were satisfied with pain management despite reporting severe pain more than one-half the time.

Responding to the need to develop tools to measure quality of life and quality of care at the end of life, the Brown University Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research and the IOM have convened a series of multidisciplinary conferences (Teno et al., 1999). The result has been a series of recommendations for a “Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End of Life Care,” with the initial target of developing tools that measure the perspectives of the dying person and the family for the purposes of research and quality improvement.

Since medical decisions increasingly are based on quality of life and quality of life is a subjective concept, cancer patients must be allowed their desired role in decisionmaking. Medical records can document treatments received and whether physicians state that they discussed treatment decisions with patients and/or their families. Even though this can be useful information, a consumer perspective on communication, decisionmaking, coordination, and other domains is important when assessing the quality of care of the dying. Ultimately, it is not documentation of the event, but whether the information was provided in a way that the cancer patient could understand and use in making decisions that should be the ultimate judge of the quality of care.

Typically, “satisfaction measures” have been relied on for the consumer perspective on the quality of health care (Table 3-4). In these cases, consumers are asked to rate the quality of care using scales ranging from either “excellent” to “poor” or “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied.” Typically, respondents must go through a cognitive process in which they first ask whether a particular event occurred, formulate their expectations regarding that event, and then rate that event using the provided response scale. Unfortunately, expectations are usually low, causing respondents to express high satisfaction with care that is less than optimal.

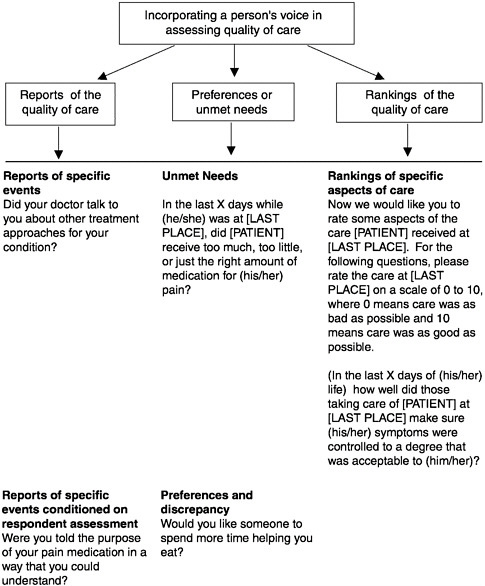

Newer methods have begun using either “patient-centered reports” (Cleary and McNeil, 1988) or “preference-based questions” (i.e., unmet needs) to capture consumer perspectives. These methodologies, unlike typical satisfaction questions that rely on ratings, provide information that can guide improvement of the quality of care. For example, knowing that 85 percent of patients believe a health care provider is “very good” does not supply that provider with information on how to improve. On the other hand, knowing that 20 percent of patients did not understand a provider’s

directions for taking pain medications does provide an important target for improving and enhancing the quality of care. Moreover, patient-centered reports and preference-based questions have strong face validity with health care providers. In the future, surveys have to rely on all three methodologies to capture the consumer perspective on quality of care at the end of life. (See Figure 3-5 for examples of questions from a bereaved family member survey to examine the quality of care for dying persons and their families.)

TABLE 3-4 Status of Quality Indicator Development for End-of-Life Care

|

Domain |

Proposed Indicators |

Readiness |

|

Pain |

Frequency and severity of pain from Minimum Data Set |

Proposed indicators require validation, but can be measured for all hospitalized cancer patients |

|

|

Major limitation: captures only health care provider perspective |

|

|

Patient and family perspective on pain management |

Instruments available (e.g., from American Pain Society or Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End-of-Life Care) |

|

|

Satisfaction |

Measures of patient satisfaction, based on patient or surrogate responses |

New instruments have undergone reliability and validity testing. Additional questions are specific for cancer (e.g., whether patients are informed of recommended treatments, access to high-quality clinical trials) and incorporation into ongoing data collection efforts |

|

New instruments include some questions relevant to people dying from cancer |

||

|

Shared Decisionmaking |

Questions from Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End-of-Life Care |

Reliability and validity testing completed |

|

|

Examination of responsiveness not complete |

|

|

Coordination and Continuity of Care |

No indicators yet available |

|

What Can We Measure with Current Nationally Collected Data? What Do We Want to Be Able to Measure in the Future?

The ultimate goal is a national system that measures the quality of care for people with cancer, from diagnosis through cure, long-term survival, or death. Good care (1) is based on scientifically sound evidence, (2) incorporates informed patients’ preferences, (3) provides access to appropriate services including high-quality clinical trials, (4) coordinates services across multiple segments of the health care “system,” and (5) is compassionate, attending to both the physical and the psychological needs of the patient and family.

Reliable indicators of quality can be powerful motivators for health care providers at all levels to improve the quality of their care. The development of quality indicators for end-of-life care remains at an early stage. At this point, there are two relevant questions: (1) for which domains is there either empirical or normative evidence to support quality indicators for the purpose of accountability; and (2) are there reliable and valid measures in existing data sets?

There is both normative and empirical evidence of the importance of pain management, something that is entirely under the control of health care systems. While the evidence is not as strong as for pain management, satisfaction also could be measured for purposes of public accountability. The evidence that health care institutions can improve satisfaction with hospice interventions is very strong (Greer and Mor, 1986; Hanson et al., 1997; Kane et al., 1984).

There is strong normative evidence based on both guidelines and court rulings that attest to the importance of shared decisionmaking (i.e., decisions regarding treatment choices that are based on informed patient preferences if the patient desires a role in decisionmaking). One last domain for which measures could be developed is coordination and continuity of medical care. Recurrent concerns in focus groups are that medical care is fragmented, that a physician often is not in charge, and that health care providers give conflicting information about treatment plans. Unlike pain and satisfaction, the conceptual framework and measurement tools for coordination and continuity of care are in need of further development.

Future Directions:

Measures of pain management, shared decisionmaking, coordination and continuity of care, and patient or family perspectives of the quality of care (i.e., satisfaction) must be developed, validated, and benchmarked. These measures have to be tested for validity and responsiveness in demonstration programs to assess the quality of care for persons dying from cancer.

Some of these domains can be examined in part with two national databases: the Minimum Data Set of Nursing Home Residents and Medicare claims files. The MDS is federally mandated and reports data from the Resident Assessment Instrument, which collects information on the presence, severity, and frequency of pain for nursing home residents at admissions, quarterly, and with changes in health status (Hawes et al., 1995; Morris et al., 1990). With computerized drug data, quality indicators can be formulated to examine the frequency and severity of pain and the degree to which pain is treated. Based on an examination of the MDS database available from five states, nearly one in four cancer patients with daily pain was not prescribed any analgesic (Bernabei et al., 1998). Although only about 10 percent of cancer patients die in a nursing home, they are often the most frail and vulnerable patients.

The MDS is a potentially useful tool for public accountability, but it has limitations. For one thing, the data are recorded by staff members, not by the patient, so reports of pain and other symptoms depend on the accuracy of proxy staff reporting. An indication that reporting may not be accurate, or at least not uniform, is the range of values found in nursing homes from 10 different states, which Teno and colleagues found to vary between 8 and 49 percent of patients reported as having daily pain (Teno, 2000b). This variation could reflect inadequate pain assessment, inconsistent pain management, or the different types of people cared for by a facility. A likely explanation is inadequate assessment, given the challenges of evaluating pain in this frail population, more than half of whom have moderate to extensive cognitive impairment.

Since July 1999, HCFA has identified a series of performance indicators that are examined based on the MDS. Experience with the use of the MDS indicators has yet to be evaluated, but there are important concerns. Specifically, the experience of nursing homes is increasingly revealing the importance of unintended consequences of applying quality indicators to populations in which they are not applicable.

For example, two of the proposed nursing home indicators focus on dehydration and weight loss. A quality indicator is composed of a numerator (e.g., those persons with pain) and a denominator (e.g., conscious persons in that nursing facility). For the dehydration and weight loss indicators, the denominator is everyone in the health care facility, including those who are dying. The potential unintended consequence is that nursing homes will increase the use of nasogastric tube feeding, IV hydration, and hospitalizations of dying individuals. The obvious and simplistic solution is to eliminate the dying patients from the denominator. However, identifying patients who are dying—particularly those dying from illnesses other than cancer—can be quite difficult given the limitations of prognostication and

knowing that the functional trajectory is relatively flat for noncancer patients (Teno and Coppola, 1999).

For Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service plans (but not in Health Maintenance Organizations), Medicare claims files collect information on charges, reimbursement, hospitalizations, hospice enrollment, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes. Researchers have used these records for a variety of purposes. Pritchard and colleagues (1998) examined the national pattern of proportion of deaths in hospitals. Wennberg and colleagues have examined records for the last six months of life to determine whether patients spent time in an intensive care unit (ICU), the number of physician visits, and whether 10 or more physicians were involved in the decedent’s care, all of which are potentially useful indicators of aspects of quality. The importance of this work is the striking variation around the country in each of these statistics (which was also found in two studies based on SUPPORT data, after adjustment for disease severity and patient preferences) (Pritchard et al., 1998; Teno et al., 2001e). However, Medicare claims data alone cannot be used as appropriate quality indicators because they lack information on disease severity and patient preferences. One way around this is to link a measure of severity (site and stage of cancer) from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to Medicare claims. Data linkages such as this are becoming easier but still require considerable development before they can be used routinely.

Future Directions:

HCFA, AHRQ, or NCI could sponsor research to develop and validate the use of quality indicators based on data from Medicare claims files.

None of the existing databases captures the patient perspective on the quality of care. The only federally sponsored effort that has attempted this is the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS; http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/cahpfact.htm). This five-year research effort has developed, validated, and used new surveys tools to capture the patient experience with managed care. The goal of CAHPS is to develop information to be used by consumers and health care purchasers in choosing managed care plans. CAHPS consists of core questions and modules addressed to specific populations (e.g., Medicaid managed care enrollees) and covering specific content areas (e.g., well-child care, prescription medicines). There is a CAHPS chronic disease module, but it is not specific enough to assess the quality of care for advanced cancer, and it would be difficult to construct a module that could do so within CAHPS.

The discussion thus far has focused on indicators to be used for public

accountability. Equally important are indicators for “quality improvement,” which takes in a range of purposes from institutional audits to identify opportunities to improve care, to indicators designed to examine the impact of small interventions tested through multiple “Plan, Do, Study, and Act” cycles. The measures used for different purposes differ, but are related, and fall along a continuum. Measures developed for quality improvement with the correct psychometric properties may evolve into accountability measures.

There are currently no quality indicators in national use that deal specifically with palliative care or other end-of-life issues. However, the degree to which indicators may be in use for QI or other institutional purposes is not known. The author contacted six NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers with strong palliative care interests to determine the extent of their current systematic efforts to examine quality of care of the dying. Only one of the centers is collecting any such information, using the NHO family satisfaction survey for people who died in an affiliated hospice program and ongoing satisfaction surveys to examine the quality of care for dying patients discharged home from its hospital. Two other centers did monitor symptoms as a “fifth vital sign.”

Future Directions:

Comprehensive Cancer Centers should set the benchmarks for excellence in cancer care, and this includes validating and reporting on quality indicators.

What Research Is Needed?

In Ensuring Quality Cancer Care (IOM, 1999), the National Cancer Policy Board recommended development of a core set of quality measures for the continuum of cancer care, including care at the end of life. The elements of quality care identified were an “agreed upon care plan that outlines the goals of care, policies to ensure full disclosure of information with appropriate treatment options, a mechanism to coordinate services, psychosocial support services, and compassionate care.” There are gaps all along the continuum of care, but nowhere more severe than for end-of-life care, for which the following are needed: the development of new measurement tools; research to both validate measurement tools and examine their real-world application in terms of responsiveness and burden; and if these measurement tools are to be used for accountability, a consensus-building process between the public, the government, and the health care industry.

The importance of guidelines has also been recognized by the NCPB and is especially true for examining quality of end-of-life care. A key question for advance care planning to formulate end-of-life contingency plans

consistent with patient preferences is, When? Guidelines that recognize different needs at different points along the disease trajectory are necessary, especially those that are of particular importance when a person accepts that he or she is dying, such as spirituality and transcendence.

Patient preferences and satisfaction are important at every stage of treatment, but they take on added significance at the end of life. The measurement tools now available are based on review of medical records or administrative data. New measures are needed that incorporate the extent to which a patient’s care is based on informed preferences, that measure whether patients receive psychological support if needed and wanted, and that they assess whether care is both coordinated and compassionate. The perceptions of the dying patient and family provide an important perspective on each of these aspects of medical care. These surveys should be developed according to a conceptual model that is based on guidelines and the concerns voiced by dying persons and their families.

Some work has been started toward surveys of bereaved family members. One effort (Teno et al., 2001a; Teno, et al., 2001b) uses current guidelines and results of focus groups from around the country to develop questions on unmet needs and on the family’s perspective of the quality of care delivered to the dying person and to themselves. A second survey (Patrick and Curtis, 2001) focuses on the quality of dying. As these and other tools are developed, some questions will be applicable to all dying persons, but there will also be a need for disease-specific questions (e.g., management of toxicity from chemotherapeutic agents is a very important concern, and the specifics of management are different for cancer patients than for those dying from other causes).

The initial work has focused on retrospective surveys of surviving family members largely because the denominator is easily defined (based on cancer registry or death certificate data) and family members are often the only ones able to be interviewed in the last month of a patient’s life. Surveys that directly capture the patients’ perspective are needed, as well, however. The design of such surveys could be linked to sentinel events or triggers (e.g., admission to palliative care or hospice program, reaching a certain disease stage), with consideration give to which domains are included and the point (or points) along the patient’s disease trajectory at which questions should be asked.

An important tension that the developers of surveys will face is between respondent’s burden and the desire to be comprehensive. The eventual goal is to minimize the respondent burden, but initially a larger number of items will be tested and a winnowing process used to arrived at a parsimonious set of questions.

The mode of survey administration is another important research question: can valid information be gathered through a self-administered ques-

tionnaire (by either the patient or a proxy respondent), or should it be professionally administered? Self-administered surveys cost less, but their validity must be demonstrated for these sensitive areas. At a later stage, it will be necessary to examine the correlation of different quality indicators based on administrative data, chart reviews, and surveys.

The constraints imposed by feasibility and cost must guide the development of quality indicators. A key consideration is to minimize the institutional burdens and maximize the value in achieving the goals of quality care for dying persons and their families. It will be important from the outset to involve health care administrators who would have to implement data collection in partnership with the development of measurement tools.

Future Directions:

Guidelines are needed that outline the triggers for when a cancer is to be considered life limiting (an implied prognosis of less than one year) and normative behaviors (such as advance care planning, discussion of prognosis and options of hospice) are expected. Such triggers should be linked to prospective surveys to measure the quality of medical care. Research to develop population-based prognostic models will be needed to help inform the selection of such triggers.

CONCLUSION

The development of quality indicators for the care of the dying person is at an early stage of development. Basic descriptions of the dying experience and the care given to people who are dying are still lacking. Clinical guidelines, important for synthesizing the available evidence and reaching consensus on what defines quality medical care, have been developed only for certain aspects of palliative and end-of-life care. These need further development within a system that allows regular incorporation of new knowledge. Such guidelines can help in defining who should be counted among the “dying.” Quality indicators based on guidelines and the consumer perspective must be developed, validated, and applied in health care settings. Such indicators must examine the structure, processes, and outcomes of health care systems. Research is needed to examine the interrelationships of structure, process, and outcome as well as the correlation of indicators using different data sources. Ultimately, we need indicators that are feasible and cost-effective, that recognize what the best medical care consists of, and that reflect the perspectives of the dying and their families.

REFERENCES

Addington Hall J, McCarthy M. Regional Study of Care for the Dying: methods and sample characteristics. Palliat Med 1995a; 9(1):27–35.

Addington Hall J, McCarthy M. Dying from cancer: results of a national population-based investigation. Palliat Med 1995b; 9(4):295–305.

American Pain Society. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee [see comments]. JAMA 1995; 274(23):1874–1880.

ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology). Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. Adopted on May 16, 1997 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15(8):2996–3018.

ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology). ASCO Special Article: Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(5):1986–1996.

Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology [see comments] [published erratum appears in JAMA 1999 Jan 13; 281(2):136]. JAMA 1998; 279(23):1877–1882.

Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians—American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132(3):209–218.

Bredin M, Corner J, Krishnasamy M, Plant H, Bailey C, A’Hern R. Multicentre randomised controlled trial of nursing intervention for breathlessness in patients with lung cancer. BMJ 1999; 318(7188):901–904.

Breitbart W, Bruera E, Chochinov H, Lynch M. Neuropsychiatric syndromes and psychological symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995; 10(2):131–141.

Brock DB, Foley DJ. Demography and epidemiology of dying in the U.S. with emphasis on deaths of older persons. Hosp J 1998; 13(1–2):49–60.

Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Quality of health care. Part 2: measuring quality of care [editorial] [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1996; 335(13):966–970.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995 ; 152(8):1185–1191.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Lander S. Depression, Hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 1998; 39(4):366–370.

Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1996; 335(3):172–178.

Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry 1988; 25(1):25–36.

Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1994; 330(9):592–596.

Conill C, Verger E, Henriquez I et al. Symptom prevalence in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 14(6):328–331.

Coyle N, Adelhardt J, Foley KM, Portenoy RK. Character of terminal illness in the advanced cancer patient: pain and other symptoms during the last four weeks of life [see comments]. J Pain Symptom Manage 1990; 5(2):83–93.

De Florio ML, Massie MJ. Review of depression in cancer: gender differences. Depression 1995; 3:66–80.

Desbiens NA, Mueller Rizner N, Connors AF, Wenger NS. The relationship of nausea and dyspnea to pain in seriously ill patients. Pain 1997; 71(2):149–156.

Desbiens NA, Wu AW, Broste SK et al. Pain and satisfaction with pain control in seriously ill hospitalized adults: findings from the SUPPORT research investigations. For the SUPPORT investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment [see comments]. Crit Care Med 1996; 24(12):1953–61.

Donnelly S, Walsh D. The symptoms of advanced cancer. Semin Oncol 1995; 22(2 Suppl 3):67–72.

Donnelly S, Walsh D, Rybicki L. The symptoms of advanced cancer: identification of clinical and research priorities by assessment of prevalence and severity. J Palliat Care 1995; 11(1):27–32.

Dudgeon DJ, Raubertas RF, Doerner K, O’Connor T, Tobin M, Rosenthal SN. When does palliative care begin? A needs assessment of cancer patients with recurrent disease [see comments]. J Palliat Care 1995; 11(1):5–9.

Dudgeon DJ, Rosenthal S. Management of dyspnea and cough in patients with cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1996; 10(1):157–171.

Edmonds P, Higginson I, Altmann D, Sen Gupta G, McDonnell M. Is the presence of dyspnea a risk factor for morbidity in cancer patients? J Pain Symptom Manage 2000; 19(1):15– 22.

Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. The promise of a good death. Lancet 1998; 351 Suppl 2:SII21–29.

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132(6):451–459.

Escalante CP, Martin CG, Elting LS et al. Dyspnea in cancer patients. Etiology, resource utilization, and survival—implications in a managed care world. Cancer 1996; 78(6): 1314–1319.

Fainsinger RL, Bruera E. When to treat dehydration in a terminally ill patient? Support Care Cancer 1997; 5(3):205–211.

Fainsinger R, Miller MJ, Bruera E, Hanson J, Maceachern T. Symptom control during the last week of life on a palliative care unit. J Palliat Care 1991; 7(1):5–11.

Farncombe M. Dyspnea: assessment and treatment [see comments]. Support Care Cancer 1997; 5(2):94–99.

Foley KM. 1979. Management of Pain of Malignant Origin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Foley KM. The relationship of pain and symptom management to patient requests for physician-assisted suicide. J Pain Symptom Manage 1991; 6(5):289–297.

Fox E, Landrum McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments [see comments]. JAMA 1999; 282(17):1638– 1645.

Glaser B, Strauss A. 1968. Time for Dying. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Goodlin SJ, Winzelberg GS, Teno JM, Whedon M, Lynn J. Death in the hospital. Arch Intern Med 1998 ; 158(14):1570–1572.

Greer DS, Mor V. An overview of National Hospice Study findings. J Chronic Dis 1986; 39:5– 7.

Greer DS, Mor V, Morris JN, Sherwood S, Kidder D, Birnbaum H. An alternative in terminal care: results of the National Hospice Study. J Chronic Dis 1986; 39(1):9–26.

Haidet P, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al. Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician-patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 1998; 105(3):222–229.

Hakim RB, Teno JM, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Factors associated with do-not-resuscitate orders: patients’ preferences, prognoses, and physicians’ judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125(4):284–293.

Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45(11):1339–1344.

Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Mor V, Fries BE, Nonemaker S. Reliability estimates for the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist 1995; 35(2):172–178.

Hay L, Farncombe M, McKee P. Patient, nurse and physician views of dyspnea. Can Nurse 1996; 92(10):26–29.

Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). Nursing Home Compare, 2000. http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/Home.asp.

Higginson I, McCarthy M. Measuring symptoms in terminal cancer: are pain and dyspnoea controlled? J R Soc Med 1989; 82(5):264–267.

Hockley JM, Dunlop R, Davies RJ. Survey of distressing symptoms in dying patients and their families in hospital and the response to a symptom control team. Br Med J Clin Res Ed 1988; 296(6638):1715–1717.

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Symptoms at presentation for treatment in patients with lung cancer: implications for the evaluation of palliative treatment. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Lung Cancer Working Party. Br J Cancer 1995; 71(3):633–636.

Institute of Medicine. 1990. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.