EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) of 1990 imposed strict new deadlines for meeting national air quality standards in nonattainment areas, including measures to ensure that transportation projects conform with pollutant reduction schedules. The 6-year, $6 billion Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) program was established in the following year. While congestion mitigation is a goal of CMAQ, the primary policy focus since the program’s inception has been on achieving the air quality goals of the CAAA by assisting nonattainment areas in meeting the new mandates. Enacted as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) of 1991, CMAQ is the first and only federally funded transportation program explicitly targeting air quality improvement.

CMAQ’s program structure reflects the basic philosophy of ISTEA: project planning and decision making are decentralized. The program sponsors—the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration, in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—provide broad policy guidance and project eligibility criteria. The states and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs)—the key agencies responsible for transportation planning and determination of conformity at the regional level—are responsible for project selection and implementation.

STUDY CHARGE

The 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) reauthorized the CMAQ program for an additional 6 years and increased its funding to a minimum of $8.1 billion, representing about 4 percent of the 1998–2003 federal surface transportation program. Questions raised about the efficacy of the program during the

reauthorization hearings, however, prompted a congressional request for an evaluation to address the following questions: How well is the program meeting its primary policy goal of improving air quality? Should more attention be paid to congestion alleviation as an important program policy goal in its own right? Can desired program outcomes, such as reduced motor vehicle trips, travel, vehicle emissions, and pollutant concentrations, be measured? Can the program’s qualitative benefits be assessed? Are CMAQ projects cost-effective relative to other pollution reduction strategies? Should the program be broadened and project eligibility expanded to cover new pollutants and emission reduction strategies? To respond to the congressional request and address these questions, the Transportation Research Board of the National Research Council appointed the Committee for the Evaluation of the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program. This report presents the committee’s findings and recommendations.

OVERVIEW OF PROGRAM OPERATION

CMAQ funding is apportioned to the states by means of a formula that takes into account the severity of air quality problems and the size of affected populations. The states are required to spend the funds in nonattainment areas [those not in compliance with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) set forth in the CAAA] and maintenance areas (those that have achieved compliance with the NAAQS and met requirements for redesignation from nonattainment status). The primary focus has been on areas designated as being in nonattainment for ozone and carbon monoxide, reflecting the pollutants of greatest concern when the CAAA and ISTEA were passed. Areas designated as being in nonattainment for particulate matter (PM10)1 became explicitly eligible to receive CMAQ funds under TEA-21, reflecting increased concern about the adverse health effects of particulates; however, the CMAQ funding formula was not revised to include particulates as a factor.

CMAQ funds are focused primarily on the transportation control measures (TCMs) contained in the 1990 CAAA, with the exception of vehicle scrappage programs, which are not eligible (see Box ES-1). TCMs, which have been part of local transportation programs since the 1970s, are strategies whose primary purpose is to lessen the pollutants emitted by motor vehicles by decreasing travel demand (e.g., reducing motor vehicle trips, vehicle-miles traveled, and use of single-occupant vehicles) and encouraging more efficient facility use (e.g., reducing vehicle idling and stop-and-start traffic in congested conditions, managing traffic incidents expeditiously). In addition, CMAQ funds may be used for projects that reduce vehicle emissions directly through vehicle inspection and maintenance programs and fleet conversions to less polluting alternative-fuel vehicles. Intermodal freight facilities, strategies to reduce particulate emissions, and public education and other related outreach activities in support of TCMs are also eligible. The funds are intended primarily for new facilities, equipment, and services aimed at generating new sources of emission reductions. Operating funds that support these projects are generally restricted to a 3-year period. The CMAQ enabling legislation explicitly prohibits funding of construction projects that provide new capacity for single-occupant vehicle travel, such as the addition of general-purpose lanes to an existing highway or a new highway at a new location.

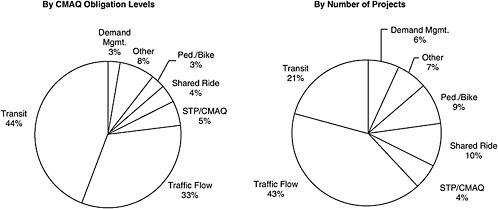

CMAQ projects can be proposed by cities, counties, transit and transportation authorities, state departments of transportation (often through their local district offices), and private and nonprofit entities in cooperation with a lead public agency. MPOs have the primary responsibility in a region for developing a consensus list of projects for funding and programming. An analysis of program obligations for the first 8 program years, drawn from an FHWA national database of all CMAQ projects, reveals that funding has been concentrated in two areas: transit and traffic flow improvements (see Figure ES-1). This pattern holds whether numbers or dollar values of projects are considered. Nevertheless, the categories include a wide range of projects—from infrastructure to operational improvements, and from more traditional measures, such as park-and-ride facilities and high-occupancy vehicle lanes, to strategies that many regions consider

|

BOX ES-1. Transportation Control Measures Included in the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, Eligible for CMAQ Funding

|

Note: HOV = high-occupancy vehicle; SOV = single-occupant vehicle. Source: FHWA (1999, 10–11). |

nontraditional and innovative, such as traffic monitoring and incident management centers, special freeway service patrols, on-demand shuttle bus services on major corridors, bus traffic signal preemption systems, and commuter ferry service.

EVALUATION CONTEXT

Any evaluation of the CMAQ program must be undertaken with recognition of the magnitude of the air quality problem in the United States and with realistic expectations concerning the influence one relatively small program can have on reducing pollution. Transportation-generated pollutants from motor vehicle emissions are only one source of poor air quality in the nation’s metropolitan areas, and influencing even this one source is not easy. Metropolitan areas have complex and varied built environments, extensive networks of transportation facilities, and travel modes dominated by drivers riding alone. Thus, most attempts to change the system will result in small modifications, although these changes can accumulate over time.

The resources provided by the CMAQ program to bring about such changes are modest by federal transportation program standards.

CMAQ funds constitute a relatively small fraction of any given region’s total transportation budget—typically on the order of 2 to 3 percent—and the funds are often widely disbursed across a diverse program of eligible activities. Moreover, relative to new vehicle emission and fuel standards that apply to large segments of the vehicle fleet, most CMAQ-funded TCMs are highly local in scale (e.g., an intersection improvement, a bicycle path). Thus, it is not surprising that estimates of emission reductions from a region’s CMAQ program amount to only a small fraction of the total emission reductions needed for a region to achieve and maintain the targets set by air quality regulations. Although the effects of any individual project may be small, it does not follow that the projects are unimportant. CMAQ-funded TCMs can help make the difference at the margin in whether an area meets pollution reduction targets and achieves or maintains conformity.

An evaluation of the CMAQ program necessarily involves a review of past performance. However, the pollution baseline against which project effectiveness is measured is changing. As vehicles and fuels become cleaner, some projects that were effective in the past may not be as successful in the future. Nevertheless, a retrospective evaluation is valuable to learn which projects have best met program objectives, and may still be effective for new nonattainment areas that become eligible for program funds. At the same time, new knowledge is emerging about the adverse health effects of various pollutants, such as particulates, that may require some refocusing of program funds and activities to target these pollution sources more directly. Thus, both a retrospective and a prospective evaluation of the CMAQ program are needed.

FINDINGS

A broad range of regional transportation planners, operating agency staff, air quality officials, and interest groups consulted for this study see value in the CMAQ program and support its continuation. Although support for the program is not universal, the positive reaction of these groups is predictable because the CMAQ program helps fund the mandates imposed on the transportation sector by the 1990 CAAA. The funds are restricted to projects that reduce pollution and congestion; CMAQ is the only transportation program with this

focus. Without this restriction, the money would likely go to other uses, such as the backlog of transportation infrastructure rehabilitation and expansion needs. For many regions that have implemented most available pollution reduction strategies, CMAQ-funded TCMs offer an additional source of reductions that can help an area meet conformity requirements. The CMAQ program also encourages regions to experiment with nontraditional projects because it is focused on new facilities and services, supports alternatives to highway projects that are popular among elected officials and citizens, and affords the opportunity to fund small demonstration projects. Given the scarcity of available funding, this focus would probably not have occurred without CMAQ. The program motivates agencies to think seriously about new strategies for improving air quality, encourages interagency consultation and cooperation, and creates an opportunity for participation by a broad constituency in project identification and development. In addition, within broad constraints, CMAQ funds can be used for a wide range of eligible activities, providing local agencies great flexibility in comparison with many other transportation programs whose funds are limited to specific programmatic areas.

It is not possible to undertake a credible scientific quantitative evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the CMAQ program at the national level. The scale issues discussed in the preceding section would make it difficult, even in the best of circumstances, to identify and segregate the effects of numerous small projects on regional air quality and congestion, much less combine them across regions. In other words, the effect of implementing CMAQ projects is generally small compared with that of other factors influencing emissions and air quality. In addition, the CMAQ program was never structured to be evaluated in a rigorous way. Methods for measuring the effects of many CMAQ-funded projects on emissions and air quality are limited at present, and few evaluations have been conducted following the completion of CMAQ projects to determine whether modeled estimates have been realized. Thus, the basic data needed to carry out a cost-effectiveness analysis are not available. Finally, the program’s highly localized character—its decentralized decision structure, the specific pollution problems of different regions, and the diversity of strategies eligible for funding—hinders the applica

tion of common evaluation measures. Project costs and effects can vary greatly within one metropolitan area, as well as among areas. Project performance depends on the transportation systems already in place, the air quality and congestion mitigation measures already implemented, and the projects (CMAQ-funded and others) implemented together with any CMAQ projects. Therefore, an impractical number of local studies would have to be conducted to aggregate local results credibly into a national total.

The CMAQ program provides an opportunity to measure the cost-effectiveness of individual projects or groups of projects at the local level. Because of the variety and sometimes innovative nature of the projects funded, the CMAQ program constitutes a valuable laboratory for learning how well different types of projects perform in improving air quality and reducing congestion. To date, however, the evaluations that have been conducted have been of limited use. One reason for this is that none of the evaluations provide direct measurements of the primary final program outcomes—changes in pollutant concentrations and congestion levels. Another is that even the more sophisticated evaluations of necessity involve estimating such crucial effects as changes in traffic volumes or trips using models or inputs derived from models that were developed for regional analysis, and hence are too aggregate to capture the effects of highly location-specific projects. Some of these models, particularly emissions models, also have untested accuracy. Yet another problem is that most evaluations of TCMs are based on projected rather than actual outcomes. As a result of these problems, the levels of uncertainty of modeled estimates of project effects in some cases probably exceed the magnitude of the effects. Even when individual studies are reliable, it is difficult to make meaningful comparisons across projects because of differences in assumptions and methods. All these problems can be ameliorated with more attention to evaluation procedures. Thus, it is possible to make great improvements in the present ability to track the effectiveness of CMAQ projects.

The limited evidence available suggests that, when compared on the sole criterion of emissions reduced per dollar spent, approaches aimed directly at emission reductions (e.g., new-vehicle emission and fuel standards, well-structured inspection and maintenance

programs, vehicle scrappage programs) generally have been more successful than most CMAQ strategies relying on changes in travel behavior. The past record indicates that control strategies directly targeting emission reductions have generally been more cost-effective than attempts under CMAQ to change travel behavior. However, the cost-effectiveness of some CMAQ-eligible TCMs—those involving regional ridesharing, regional transportation demand management, and some pricing strategies—compares favorably with that of non-CMAQ-eligible control strategies. There is considerable uncertainty about these conclusions, however. First, the comparisons are based on estimates of emission reductions for the ozone precursors only (i.e., volatile organic compounds and oxides of nitrogen); estimates for carbon monoxide and particulates were not available, so that the value of projects that address these pollutants is understated. Second, the wide range of cost-effectiveness results for TCMs, even for the same type of CMAQ strategy, suggests that performance depends largely on context, that is, on where and how the projects are executed. Third, many TCMs may have benefits other than pollution reduction (e.g., congestion relief, ecological effects). Finally, the estimates for nearly all strategies are affected by modeling uncertainties. Modeled estimates have generally tended to overestimate emission reductions. These uncertainties are magnified for TCMs, which require predicting the travel as well as the emission effects of projects, adding to the uncertainty of the estimates.

The historical performance of CMAQ projects does not provide a basis for confident projections about the future cost-effectiveness of these projects. Since the CMAQ program was enacted in 1991, the vehicle fleet has gradually become cleaner as newer vehicles meeting more stringent emission regulations have come to make up a larger share of the fleet, and alternative-fuel vehicles have become more common. These changes will alter the relative desirability and cost-effectiveness of different strategies. For example, it will probably be increasingly difficult to find cost-effective projects that address both congestion and air quality; traffic flow improvements undoubtedly had greater impacts when cars were “dirtier.” Automobile emissions are increasingly a function of the small number of dirty cars and of certain types of driving, a fact that enhances the value of such strate

gies as use of remote sensing2 and well-structured inspection and maintenance programs to detect and possibly repair heavily polluting vehicles, and vehicle scrappage programs designed to take these vehicles off the roads. Once cost-effective strategies have been applied in a nonattainment area, more stringent versions of these programs (e.g., enhanced inspection and maintenance, regional ridesharing) to achieve further emission reductions would probably be adopted only at much higher cost. As knowledge about the adverse health effects of such pollutants as particulates grows, strategies focused on diesel trucks and buses—the primary transportation-related emitters of these pollutants—may have important benefits.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The quantitative evidence reviewed by the committee on the benefits of the CMAQ program did not provide a strong basis for either supporting or opposing continuation of the program. Nonetheless, on the basis of its review of the available qualitative as well as quantitative evidence on program effectiveness, the committee reached a consensus on the following recommendations, which are broadly grouped in response to the study charge.

Program Continuation and Focus

1. The CMAQ program has value and should be reauthorized with the modifications recommended below.The potential benefits of the CMAQ program are sufficiently great, in the collective judgment of the committee, to warrant its continuation. This judgment is made despite the inadequacy of the data to support an overall quantitative cost-effectiveness evaluation, for the following reasons. First, CMAQ is the only federally funded transportation program explicitly targeting air quality improvement. Arguably the most important benefits of the CMAQ program are the incentives and resources provided to local agencies to think seriously about strategies for improving air quality and reducing congestion. Second, the funds provided are restricted to these purposes, offering an opportunity for

local nonattainment areas to experiment with nontraditional transportation approaches to pollution control, and to forge new partnerships and greater interagency cooperation in the development of such approaches. Third, some of the most promising TCMs in terms of cost-effectiveness (according to admittedly uncertain data) receive limited if any support from traditional transportation funding sources and thus depend on the CMAQ program for a full exploration of that promise. Fourth, the program helps nonattainment and maintenance areas fund the strict mandates and pollution control schedules required by the 1990 CAAA. Finally, CMAQ provides a flexible source of funds that can be used for a wide range of activities tailored to local pollution and congestion problems.

2. Air quality improvement should continue to receive high priority in the CMAQ program. Although the program was conceived to address both congestion mitigation and air quality goals, in practice the latter have been given greater weight in the program structure. Maintaining this focus on air quality is desirable because congestion management is already addressed by the much larger share of federal highway funds spent on infrastructure. The CMAQ program’s legislative restriction on projects involving construction of new highway capacity should also be maintained, given the availability of other funding sources for those projects and their uncertain effect on air quality. Where it can be demonstrated that CMAQ-eligible congestion relief projects may make important contributions to emission reductions, those projects should be supported by the program. The primary criteria by which the cost-effectiveness of congestion relief and more generally all CMAQ-eligible projects are judged, however, should relate to the reduction of air pollution.

3. Consistent with maintaining a focus on the air quality dimensions of the program, state and local air quality agencies should be involved more directly in the evaluation of proposals for the expenditure of CMAQ funds.Program regulations encourage consultation with state and local air quality agencies in the development of appropriate project selection criteria and the agencies’ involvement in project and program funding decisions, but the case studies conducted for this study suggest a more limited role in many regions. Air

quality agencies are expressly charged with reducing emissions of air pollutants and meeting national air quality standards, and many are knowledgeable about pollution problems and cost-effective control approaches. Thus, the role of air quality agencies should be strengthened so they can be more meaningful participants in the CMAQ project review process.

Program Scope

4. The components of air quality addressed by the CMAQ program should be broadened to include, at a minimum, all pollutants regulated under the Clean Air Act.To date the CMAQ program has focused primarily on ozone and carbon monoxide. Yet it is incongruous, for example, that particulates, now believed to pose a greater health hazard than any of the other criteria pollutants, are included in the CMAQ program only for project eligibility, not as part of the funding allocation formula. At a minimum, the eligibility criteria and allocation formula should include all pollutants regulated under the Clean Air Act, which would cover particulates, as well as sulfur dioxide and air toxics. Any changes to regulated pollutants, such as implementation of new standards for fine particulates (PM2.5), should automatically be reflected in the eligibility criteria and funding formula. Moreover, when U.S. policies are put in place to address carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions, these other emissions should be considered for eligibility for CMAQ funding.

5. Any local project that can demonstrate the potential to reduce mobile source emissions should be eligible for CMAQ funds. The CMAQ program should encourage MPOs to select and approve the most cost-effective local strategies available for reducing mobile source emissions. For example, vehicle scrappage programs, which appear to be more cost-effective than many other types of projects routinely approved under the program, should be eligible for CMAQ funding. Current restrictions on the use of public funds for private purposes should be reviewed to permit such programs. Regions should also consider wider use of CMAQ funds for projects focused on heavy-duty diesel vehicles and freight transport that can demonstrate the potential to reduce particulate emissions.

6. Restrictions on the use of CMAQ funds for operating assistance should be relaxed if it can be demonstrated that using funds for this purpose continues to be cost-effective. The restriction on using CMAQ funds for operating expenses of newly initiated CMAQ projects for more than 3 years creates an incentive for making capital expenditures that may not be efficient, and may arbitrarily eliminate some cost-effective operating expenditures. The committee, however, recognizes that not all operating subsidies are cost-effective or will continue to be so. Thus, it recommends that all proposed CMAQ projects—capital or operating—be evaluated through a process, outlined below, that should help establish the cost-effectiveness of proposed and funded projects.

7. The use of CMAQ funds should be considered for land use actions designed to establish the conditions for long-term reductions in future mobile source emissions. The potential of land use strategies to reduce congestion or vehicle emissions is complex and unclear. There appears to be some evidence to support the link between urban design (i.e., the relative location of activity and housing, mixed-use design) and encouragement of travel modes other than the automobile. Thus with further study, projects that support transit- and pedestrian-oriented development might be made eligible for CMAQ funding.

Program Operation

8. The agency responsible for CMAQ project selection in each nonattainment area should develop a process by which projects can be identified, selected, and evaluated in the context of the specific air quality and congestion problems of that region. In turn, the federal CMAQ project approval process should be streamlined. The committee believes many nonattainment areas could do a better job of selecting projects for CMAQ funding that are linked more closely to the specific air quality and congestion problems of the region, and of developing the information needed to determine whether project and program objectives have been accomplished. For example, to help identify the most effective strategies, the lead agency could consult with local experts on the specific pollution and congestion problems of a region and examine the steps already taken or under

way to address those problems. Within this context, objectives for an area’s CMAQ program could then be defined and measurable performance indicators developed so that individual project outcomes could be quantified. At a minimum, these indicators should include measures to estimate pollution reduction, but it would also be desirable to define and measure other effects, such as congestion mitigation and, where appropriate, effects on ecosystems or on economic development. With greater ability to measure regional program performance against objectives, responsible local agencies should be in a better position to document the effects of CMAQ projects, report on those effects to their constituencies, and provide more complete inputs to FHWA’s national CMAQ database that could be used for evaluation purposes.

Projects should be precertified as long as a region can demonstrate that they are consistent with the program objectives outlined above. Determinations of project eligibility by federal program sponsors would no longer be required once a nonattainment area had instituted a process along the lines just described. The federal project approval process should be relaxed in exchange for the regions’ development of more rigorous procedures for the selection and evaluation of projects for CMAQ funding.

Program Evaluation

9. Recipients of CMAQ funds should be given incentives to conduct more evaluations of funded projects, and federal program sponsors should provide guidance on best practices for these evaluations. One of the greatest benefits of the CMAQ program may well be the development of new strategies that can be adopted by other localities or incorporated into subsequent federal legislation. This benefit is now largely lost because there is no reliable way to gauge the success of different strategies. Local agencies must currently document the expected emission reduction potential of funded projects. They should also be expected to conduct more follow-up to determine whether the reductions have been realized and examine the factors that have made a project successful. The committee realizes it would be impractical for a region to evaluate all its CMAQ projects. Likely candidates include individual projects that are expensive or

controversial and groups of small projects (e.g., bicycle projects or traffic signal improvements) that together have measurable effects. FHWA, in consultation with EPA, should provide program recipients with guidance on best practices for conducting such evaluations, including examples and contacts for additional information.

Although program recipients might prefer the funds to be reserved for projects, evaluation is in the interest of both federal sponsors and local recipients, and thus is an entirely appropriate use of CMAQ funds. The best incentive to encourage more local project evaluation is to provide additional funds for this purpose.

10. A more targeted program of evaluation should be undertaken at the national level, to include in-depth evaluation studies, synthesis and dissemination of results, research on appropriate analysis methods, and monitoring. The CMAQ program offers a rare opportunity to evaluate a diverse group of implemented projects whose primary purpose is to improve air quality and reduce congestion. FHWA, in consultation with EPA, should take the lead in initiating a well-focused national program of evaluation financed by CMAQ funds set aside for this purpose. The program would fund a selected group of studies—perhaps drawing on a representative sample of CMAQ projects both within and across regions—in which competitively selected researchers would work with local agencies to collect baseline data and track project performance using credible evaluation criteria. FHWA or EPA should synthesize the results of these studies and maintain a cumulative database for their broad dissemination. Appropriate research designs, methods, and models for conducting evaluations of difficult-to-measure TCMs are also appropriate topics for study, but CMAQ should not be the sole funding source for this purpose because the results will have application well beyond the program. Finally, a national evaluation effort should include a monitoring component to maintain currency with the state of science relevant to the CMAQ program.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Since its inception nearly a decade ago, the CMAQ program has provided nonattainment areas with a modest but valuable source of funds dedicated to meeting the air quality mandates set forth by the CAAA.

The program has offered incentives for regions to develop effective local pollution control and congestion mitigation strategies, drawing from a wide range of eligible projects. It has also encouraged broad participation by local agencies and public interest groups in strategy development, and has enabled them to experiment with nontraditional and innovative approaches. The committee believes that if the program is reauthorized on the basis of the above recommendations, program sponsors should be in a better position in the future to account for the cost-effectiveness of implemented projects, to evaluate the success of different strategies, to monitor advances in scientific knowledge and modify the program accordingly, and to share this information widely among program recipients and the general public.

REFERENCE

Abbreviation

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

FHWA. 1999. The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program Under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21): Program Guidance. U.S. Department of Transportation, April.