Page 182

Small Business and the Macro Economy: Some Observations

Clifford G. Gaddy

The Brookings Institution

The general economic environment is critical for understanding the prospects of small business in any country, including Russia. In this presentation I will discuss the recent evolution of the Russian economy and comment on how it might be expected to develop in the years ahead. But before doing that, I will make a couple of observations about the nature and role of small business in market economies.

SMALL BUSINESS IN THE ECONOMY

Observation 1: Although the small business sector is undeniably a vital part of a modern market economy, it is not the core of such an economy. More importantly, small businesses cannot and should not be expected to “save the economy,” not even a local economy, much less a national economy.

The United States has perhaps the largest small business sector of the Western advanced economies. There, in the 1990s, small business accounted for approximately half of total private-sector employment and output. Yet, even in the United States, small businesses play an auxiliary role. Or, more correctly, they play multiple auxiliary roles, as they do in all countries. Those roles differ depending on the state of evolution of the economy and its overall health.

In a thriving economy, small businesses represent the most dynamic, innovative, and risk-taking sector. In a declining economy, or simply one that has low living standards, small businesses are a survival, or coping, mechanism. These are not mutually exclusive roles; the two types of small

Page 183

business will be observed in all economies. But the relative shares of

the two types differ.

One feature that both the innovative and the survival-oriented small businesses share is that they are highly mobile. Small businesses are easier to establish than large businesses, and they are easier to shut down. (In economists' jargon, “entry” and “exit” are easier for small businesses.) They can more easily shift their orientation in terms of the market they target or the products and services they produce.

Because of this flexibility, small businesses allow individuals (the entrepreneurs) to take advantage of better opportunities as well as to cope with a risky, unpredictable environment. In the United States in the prosperous decade of the 1990s, small businesses accounted for 75 percent of net new jobs—a share that is larger than their share of total employment. In a recession, we can expect small business to account for a disproportionate share of job losses. The message is: Small businesses are more volatile. They grow faster, but they also die faster.

Every year in the 1990s, about 10 percent of U.S. small businesses went out of existence. (This represented about half a million firms each year.) But only about 10 percent of the firms that shut down business actually went bankrupt. The other 90 percent were voluntary shutdowns. Moreover, when asked about the reasons for closing the business, the majority of firm owners responded that their businesses were successful at the time they shut them down. Why, then, did they close? The answer has to do with the economist's notion of “opportunity cost”: the owners judged that the resources that were being used in the old business, even when it was successful, could be used even more profitably somewhere else.

Small businesses do not determine the state of the economy as much as they reflect it. They are, in particular, very dependent on the institutions of a modern market economy. For instance, 75 percent of American small businesses obtained credit from outside. In other words, their health depended on the health of the financial system.

Small businesses in the United States also depend on a healthy government budget, since they are part of the federal contracting and procurement system. No less than 28 percent of federal contracts went to small businesses. While this is less than their share of the private sector (which, recall, is about 50 percent), it underscores the way in which small businesses are integrated into and dependent upon the overall economy.

Observation 2: While small business cannot save the entire economy, there are specific tasks the small business sector can help solve. Policy towards small business should not be based on exaggerated expectations but rather on clearly defined and realistic goals.

As stated above, the roles that small business plays in an economy are varied. They range from helping citizens to cope under conditions of

Page 184

economic hardship, at one extreme, to the development of high-tech

world-class industries, at the other extreme. Depending on a

country's situation, those roles can both be important and

deserving of support. Different policies will be necessary to help

them fulfill those different roles.

It is important to have a strategic view of the country's economic development in order to decide on specific policies towards small businesses. Knowing the prospects for the general economic climate is critical. Policies to promote small businesses to solve any economic task beyond using them as mere survival mechanisms will be costly, in the short and middle term. The availability of resources depends on the overall economy. Let us now then turn to the picture of Russia's economy now and what might be expected in the months ahead.

A BRIEF REVIEW

The Russian economy has seen extraordinary changes in the past three years. After the government's default on its domestic debt in August 1998 and the subsequent paralysis of its payments system, output plunged to the lowest levels ever in a disastrous decade. But by the beginning of 1999, a strong rebound had begun. For one full year, the economy showed not just steady, but accelerating growth. Gross domestic project (GDP) growth rates reached a peak of 10–12 percent on an annualized basis in late 1999.

Since then, the economy's performance has become more moderate. Although it is natural that the economic rebound would gradually attenuate, and although the balance is still positive, there are some worrisome signs. This year, some major sectors of industry have even begun to show declines in output, in profits, and in investment. It is a good time to pause and ask what is it that has happened to the Russian economy after 1998. And what can be expected over the longer term?

Figures 1 through 3 give a snapshot of the economy from early 1998 through mid-2001. They use a few selected official Russian government statistical series to illustrate the production side as well as the welfare side. The figures are based on monthly statistics for year-to-year growth or decline. To smooth out temporary fluctuations and better show the trends, they are presented in the form of six-month rolling averages. In other words, each data point is the mean of the values for the preceding six months. For instance, the data point for June 1998 represents the average values for January through June, July's value is the average of February through July, and so on. (Smoothing the data in this way not only permits us to discern actual trends more clearly; it also helps minimize the measurement and reporting errors that plague Russian statistics.)

Page 185

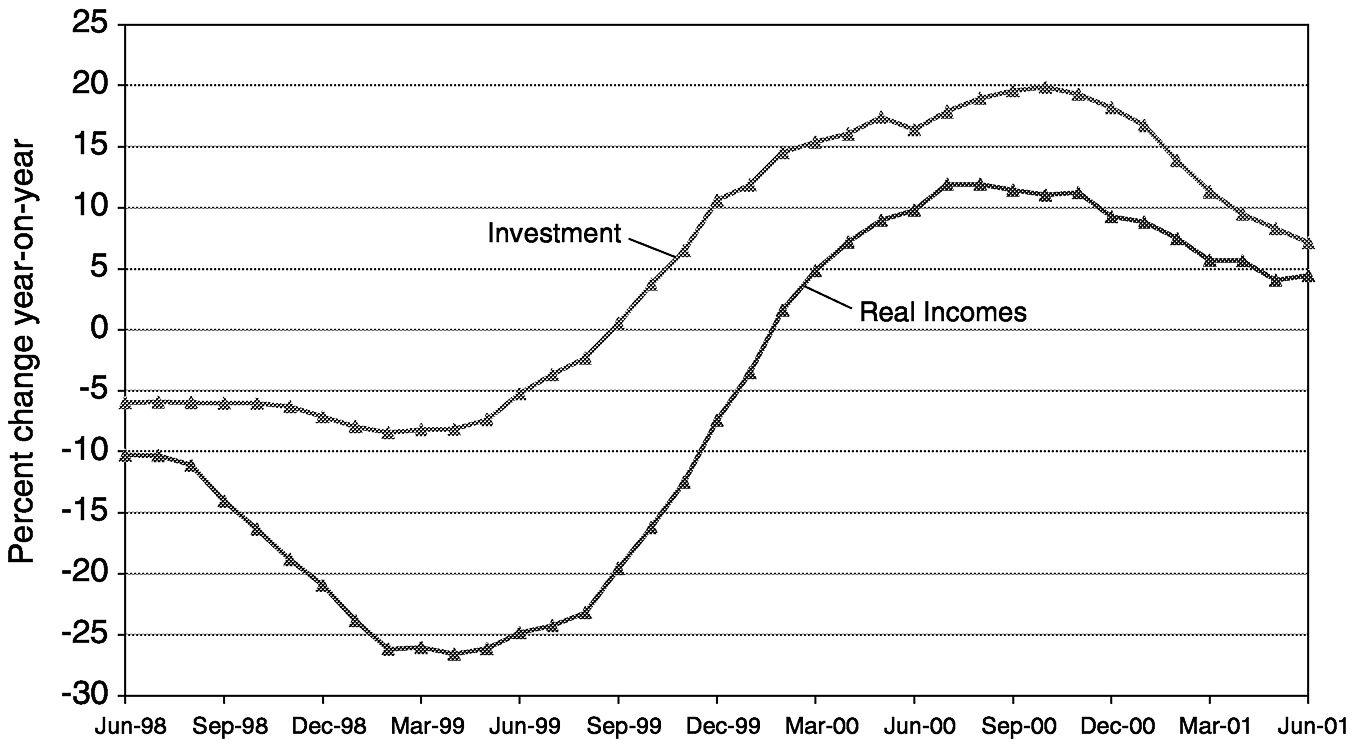

FIGURE 1 Industry and transport.

~ enlarge ~

Figure 1 focuses on the production side. The two curves show industrial output and freight transport—both measured in physical units. Although the industrial output measure is more volatile, the two data series show the same general pattern: They were negative in 1998 (even before the August financial collapse); they rebounded strongly in 1999; and finally, they tapered off in 2000 and 2001, while still so far remaining positive.

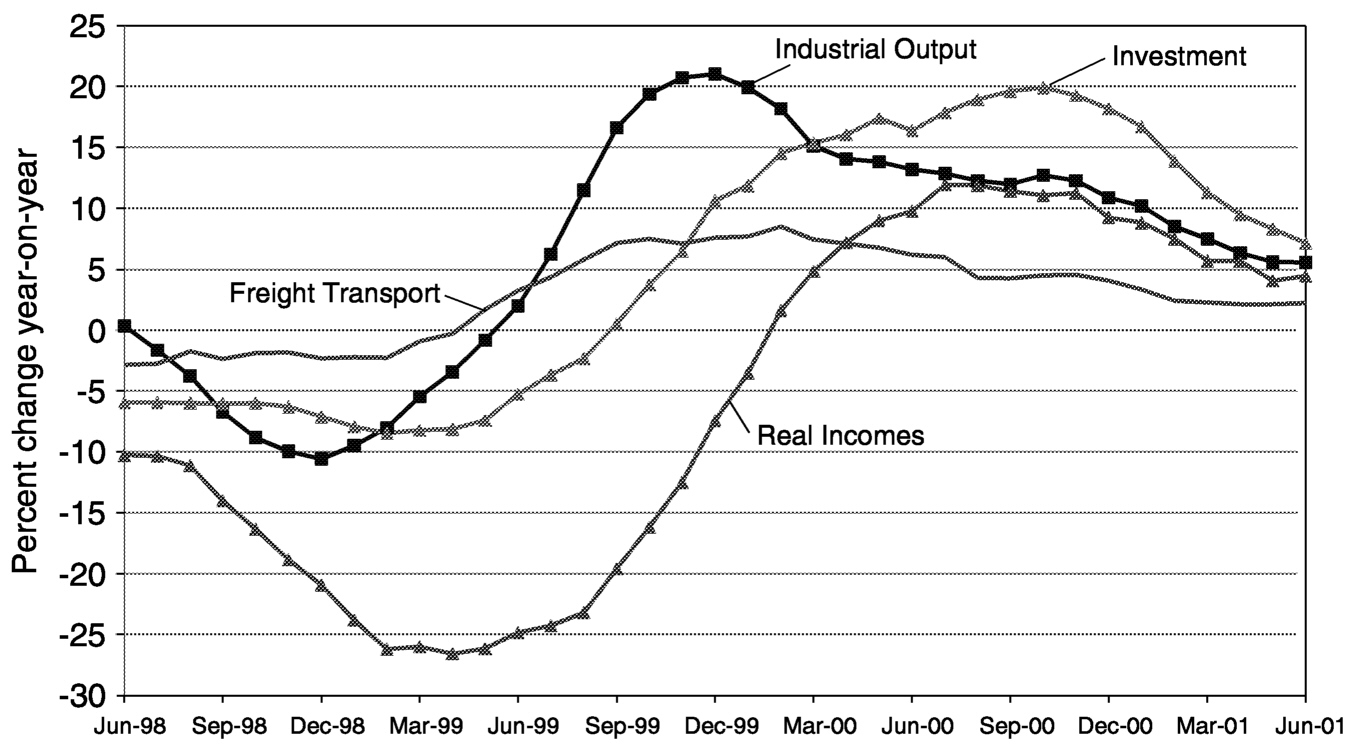

Figure 2 shows some of the follow-on effects of the trends in the production sphere. It looks at household incomes and capital investment.

FIGURE 2 Investment and incomes.

Page 186

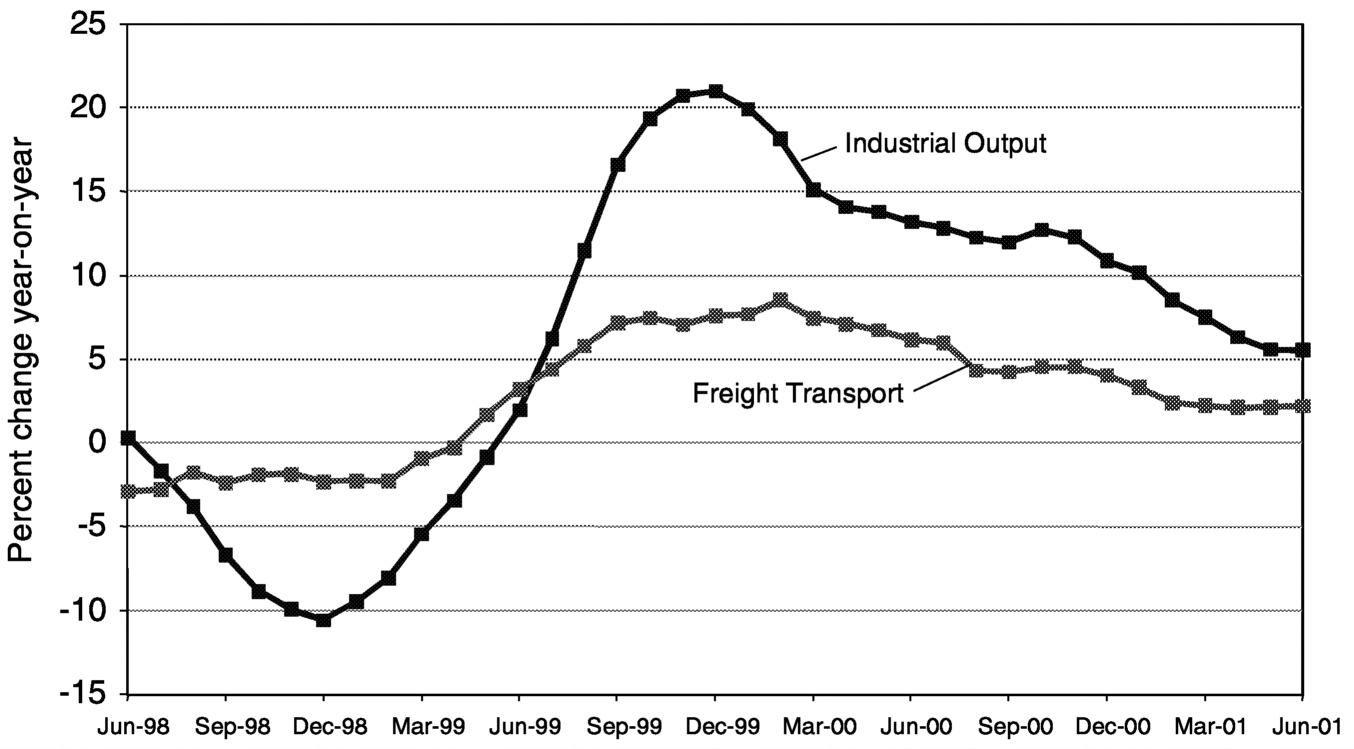

Note that the pattern is the same as in the production measures: decline, rebound to ever-higher growth rates, and tapering off. As would be expected, there is a difference in timing—a six-month to one-year lag—as compared to the first figure. This becomes clearer when we superimpose the two charts and look at the four indices together ( Figure 3). Despite the variation in volatility and in the timing over the entire three-year period, there is in the end a kind of convergence. So far, all four indices remain positive.

FIGURE 3 Comprehensive presentation of economic indicators.

ACCOUNTING FOR GROWTH

There are two principal explanations for the patterns shown by these curves. The first is the increase in world oil prices. The second is the depreciation of the Russian ruble relative to the dollar and other major currencies.

Oil Prices

It is hard to avoid the importance of the world price of oil for the Russian economy. Russia exports such large quantities of crude oil and various oil products that every dollar's increase in the price of a barrel of petroleum translates into roughly $1.5–$2.0 billion of additional yearly export revenues. The world oil price rose from barely $10 a barrel in February 1999 to more than $27 a barrel a year later, continuing eventu

Page 187

ally on up to more than $30 before it began a gradual decline. This is roughly the same trend as noted in Russia's industrial output.

In fact, the relationship between oil prices and industrial output is so close that it is tempting to ascribe virtually all of Russia's post-August 1998 economic performance to oil. That is, all the other factors that are assumed to influence economic performance—exchange rate dynamics, monopolies' pricing policy, taxes, investment rates, competition policy, capital flight, banking reform, monetary policy, and progress on corporate governance and “rule of law” —would be irrelevant. In fact, it would be a mistake to ignore those factors. Without the oil price rise, Russia would not have had its boom; but without sensible economic policy, things could have been a disaster. Or, to take it the other way around, sound policy allowed the Russian economy to take advantage of the oil price increases, but that sound policy could not have been a substitute for the oil price effect.

Devaluation

The second obvious economic factor that has been important for the post-1998 economy is the real devaluation of the ruble that occurred in the wake of the crisis. This was the consequence of a nominal depreciation that exceeded ensuing inflation. By the end of 1998 the real value of the ruble relative to the U.S. dollar was about 36 percent of its July value.

This dramatic devaluation benefited many Russian producers. For exporters of commodities whose prices were denominated in dollars on world markets, the effect was immediate. Their costs were primarily ruble based, while each dollar they earned was now worth many more rubles than before. Hence, even without making any changes in the way they did business, the exporters saw dramatic improvement in their profit and loss statements.

The devaluation was also important for Russian producers that sold their products on the domestic market in competition with imported goods. In response to this dramatic rise in prices of imported goods, Russians turned to cheaper domestic products. That in turn led to a boost in output and profits in the domestic consumer goods sector (mainly the food and light industries), but it was a one-time result. Output there is now flat, or down. In 2000, real profits in light industry were down 20 percent from 1999 levels; in the first half of 2001, they dropped another 34 percent.

WHAT REMAINS?

Both the oil price and the devaluation effects are temporary. Although they provide a windfall while they last, they cannot contribute

Page 188

to making the economic recovery sustainable except to the extent that they change the underlying structure of the economy. What we need to know is whether the windfalls from high oil prices and the cheap ruble were used to make the economy more competitive than in 1997 once the high oil prices and cheap ruble themselves are gone.

One obvious place to look is capital investment. AsFigure 2showed, investment picked up in late 1999 and continued to grow vigorously through 2000. However, we must remember that the economy began from a low base. Investment in the Russian economy fell in the 1990s even more than output. By 1997 the economy was spending only one-quarter as much on new plant and equipment as it had in 1990. This means that even the growth rates of 20 percent per year that were reached in the second half of 2000 were quite modest in absolute terms. And the current rate of growth—6–7 percent per annum—is all the more inadequate.

Moreover, the rates of fixed capital investment continue to drop. Recent figures show that more than a third of Russia's regions invested less, not more, in the first half of 2001 than they did in the first half of 2000. The regions that showed declines in capital investment included such important economic centers as the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, and the regions of Krasnodar, Stavropol, Nizhny Novgorod, Saratov, and Sverdlovsk.

Similarly disturbing trends emerge when investment is disaggregated by sector. The food industry, for instance, invested 15 percent less in the first half of this year than it did in the first half of 2000. Investment by machine-building and metalworking enterprises was down by 18 percent. For the time being, oil and gas continue to carry the rest. The oil and gas sector invested 19 percent more than last year. (And remember that oil and gas invests about 10 times as much as either heavy manufacturing or the food industry.) Thus, not even by the crudest of measures, gross capital spending, has the opportunity afforded by the devaluation and oil price rises been used to appreciably upgrade production capacity in most of the economy.

Perhaps the single most telling fact about what has and what has not been accomplished in the past three years is that despite extraordinarily favorable recent conditions, a staggeringly high proportion of Russia's industries remain unprofitable. The 1998 devaluation did reduce the number of loss-making enterprises somewhat, from more than 50 percent to around 40 percent, but the improvement stopped at that point. Thus, for three years now, some 40 percent of Russian industrial companies are still not profitable. Russia thus remains burdened by tens of thousands of nonviable enterprises that cannot compete and yet live on year after year, no matter what the macroeconomic and policy environment.

Page 189

Today the spectacular growth rates of Russia's economy in 1999 and 2000 have slowed considerably. The slowdown in the world economy and the large decline in world oil prices now threaten growth even more. As growth contracts in Russia, it is inevitable that government budgets will become tighter. It is likely that local and regional budgets will be most affected. This means that some ambitious plans for small business promotion will be threatened by lack of funding.

The ups and downs of the general economic climate must, however, not be taken as reason to abandon all efforts to promote small business. What is most important is that governments at all levels draw up plans on the basis of realistic assessments of the economic future and that they commit themselves to implement those plans over the longer term.