OVERVIEW

The Department of Energy (DOE) is responsible for cleanup and closure1 at over 140 contaminated sites in the United States. These sites are part of the legacy of nuclear-weapons production during the Manhattan Project and the Cold War. Contamination at many of these sites will continue to pose hazards that make unrestricted access unacceptable and thus entail management burdens into the indefinite future. DOE calls its activities beyond closure of contaminated sites “long-term stewardship” (LTS).2 While DOE is exploring the possibility of handing off LTS responsibilities to another agency, it currently seems likely that DOE will remain the steward at most closed sites.3

The Committee on Long-Term Institutional Management of DOE Legacy Waste Sites: Phase 2 was formed by the National Research Council at DOE’s request to

analyze long-term institutional management4 plans and practices for a small group of representative DOE legacy waste sites and to recommend improvements. (See Appendix A for the full statement of task and Appendix B for brief biographies of the committee members.) The committee selected the first two sites for its data-gathering meetings, Fernald and Mound. The third site visit, to the uranium mill tailings pile and surrounding land at the Moab Site, was part of a congressionally mandated study that was added to the committee’s original effort. The committee issued a report addressing issues at Moab in June 2002 (NRC 2002a), as requested by Congress. Appendix C lists the presentations, discussions, and tours that were part of the committee’s public meetings.

In July 2002, the assistant secretary of energy for environmental management, Jessie Roberson, requested that the study be wrapped up in advance of its planned October 2003 completion date. Following consultation with the committee and deliberations concerning the request, the Board on Radioactive Waste Management, which oversees the committee’s work, asked the committee to end its information-gathering activities and to prepare a status report based on its work to date (see Appendix D) with the understanding that the committee would therefore be limited in its ability to address fully the statement of task.

The report addresses the task statement by developing lessons that could be learned from the sites it visited and the documents it reviewed, focusing on high-level issues related to improving planning and implementation of LTS at DOE legacy waste sites:

-

what LTS is;

-

what it means to incorporate LTS in all phases of environmental management;

-

DOE’s need for a discussion of values and principles for decision making, so as to

-

enable DOE to pursue its unfamiliar responsibilities in LTS, instead of being limited by its current emphasis on compliance with existing regulations. That emphasis hinders DOE’s ability to fulfill its LTS obligations.

Public participation, trust, and confidence are essential elements of success for DOE, and are also a discussed in this report. A description of the committee’s observations from the site visits can be found in Appendix E.

Individual members of the committee are familiar with environmentally hazardous sites both within the DOE complex and outside it. The report is based on what the

committee has found in visiting three DOE sites, reviewing documents relevant to LTS at these three and other DOE sites,5 and engaging in discussion with DOE staff and others.

BACKGROUND

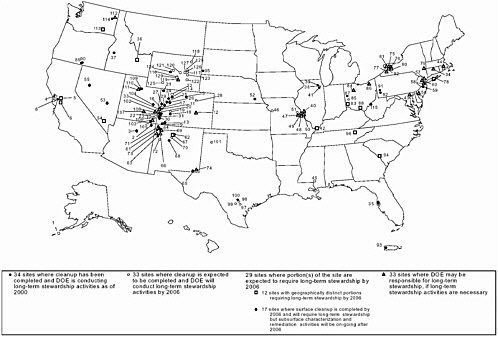

For fifty years following the beginning of the Manhattan Project in 1942, the U.S. government produced and processed nuclear materials for the nation’s defense. The industrial complex built for this effort was assembled in haste during World War II, took its mature form before environmental awareness and regulations were in place in the 1970s, and produced substantial waste and contamination at well over a hundred sites (see Figure 1) (Crowley and Ahearne, 2002).

During the decades of the Cold War the Atomic Energy Commission and its successors, the Energy Research and Development Administration and DOE, made many choices with respect to waste storage, waste disposal, routine emissions, and operations that shaped the hazards that remain at sites across the complex. These hazards, in turn, created some of the LTS problems and framed the options for dealing with them. For example, it is infeasible to relocate for disposal much of the waste that was injected underground or has leaked into the soil at Hanford because it is now contamination in the subsurface rather than discretely contained waste. These choices distributed costs and risks across geography and between present and future generations, often with limited understanding of their long-term implications for humans and the environment.6 DOE and its predecessors have been making choices with serious LTS implications for a long time. Those choices were made implicitly, as part of decisions about our national defense program. The current DOE remediation and site management program is different: Its decisions center on allocations of costs and risks, without being subordinated to another mission. The combination of current technological capabilities and funds for cleanup leave little doubt, however, that many of the contaminated sites cannot be cleaned up enough to permit unrestricted human access. Some of the remaining hazards are likely to pose significant risks indefinitely.

Contaminants are found in buildings, equipment, surface and subsurface materials, surface water, ground water, flora, and fauna. Some contaminated materials can be removed to disposal facilities specifically selected and designed to isolate chemical and radioactive wastes or they can be removed and remediated by treatment; some of the contaminated media at a site can be excavated and sequestered in on-site disposal cells; and some of the contaminants will remain in the subsurface, including ground water, under conditions that make their removal time-consuming or prohibitively costly. Wastes to be sent to disposal facilities are found in storage tanks, containers, and old disposal areas, some of which were little more than trenches that provided meager

isolation and created additional contamination that requires cleanup. The disposal facilities and contaminated media that remain in place will require LTS.

At some sites the residual hazards will decline relatively quickly because of rapid radioactive decay or biodegradation, for example, sites contaminated with tritium, which has a half-life of 12.3 years. At many sites the hazards will persist for centuries (e.g., Cs-137 and Sr-90 have half-lives of about 30 years), millennia (e.g., Pu-239 has a 24,000-year half-life), or essentially forever (e.g., uranium and stable heavy metals).

Quantified examples of the consequences if institutional controls7 or other planned LTS measures fail are few. This is because there are few risk assessments that examine loss-of-control scenarios. But it is useful to consider the case of uranium ore processing sites. If institutional controls for cleanup and disposal of wastes fail at such sites, lifetime cancer risks to persons exposed to these wastes could easily be in excess of 10-2, and in some cases could far exceed this risk level.8 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) requires in its regulations assurance that passive physical (engineered) controls be effective for at least 200 years and recognizes the need for institutional controls as a backup to physical control measures,9 yet the hazard will endure far longer than that.10 Simply meeting the standard and initially complying with the regulation could result in risks that would likely be unacceptable at sites operating under different regulations. For example, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) allows for consideration of cost-risk tradeoffs for risks below 10-4, but requires action above that risk level. As a consequence of the duration of the hazards and of the potentially significant consequences of failure, the challenge of long-term management of these and other DOE legacy waste sites is both

novel and difficult: to assure the protection of human health and environment far beyond the conventional time frame of public policy or institutional endurance.11

DOE recognized, earlier than did many other government agencies facing similar problems, that it needed help in understanding LTS and in formulating strategies for addressing its unusual requirements. Several researchers and organizations have provided analyses, among them Probst et al. (1998, 2000), the National Research Council (NRC 2000a), Russell (1998, 2000, 2002), the Environmental Law Institute (ELI 1998), and Pendergrass (1999). Citizen and stakeholder groups have provided ideas and perspectives of their own (RFSWG 2001; EUWG 1998a, 1998b; STGWG 1999; Stewardship Working Group 1999). In the last several years, DOE’s Office of Long-Term Stewardship has begun to flesh out the LTS challenge and to develop policy guidance (DOE 2001a, 2001b, 2002a, 2002b; INEEL 2002).

DOE also is pressing to accelerate cleanup and reduce cleanup costs at its sites. One way to end cleanups sooner and to reduce near-term costs is to rely more on LTS. Some people, however, are wary of DOE’s promises regarding LTS, and this wariness undermines and constrains DOE’s ability to speed remediation.12

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND OBSERVATIONS FROM THE VISITS TO MOUND AND FERNALD

To inform its deliberations, the committee visited two DOE sites in Ohio, Mound and Fernald, as well as the Moab Site in Utah. The committee’s observations from the Ohio sites are discussed in some detail in Appendix E, and the committee’s work on the Moab Site was published previously (NRC 2002a).

In Ohio, the committee found that if the remedial actions now underway at Mound and Fernald succeed (including, ultimately, the relocation of the silo wastes from Fernald), both sites seem to present low environmental risks even if their projected LTS activities were to fail. This cannot be stated without reservation, however, because assessments of failure scenarios have not been carried out at either location. At both sites a measure of trust has developed among the local public, site contractors, regulators, and DOE’s Ohio Office. All parties mentioned good working relationships, within which conflicts can be aired and addressed. Engineering analyses at Fernald seemed to be of high caliber and work on habitat development at the site is remarkable if only for the fact that ecology is being addressed at all. The process of releasing

buildings for reuse one by one at Mound—rather than the standard approach of dividing the site into a small number of operable units, so as to develop a more comprehensive, integrated understanding of the site—seemed to encourage cleanup managers to make do with the information and tools already available.

Chief Finding: The committee observed a compartmentalization of cleanup planning and LTS planning at the sites visited: cleanup planning and execution will conclude at a site, and LTS is left to address the resultant end state.

The Ohio sites are only now beginning to address LTS issues, as they near the end of cleanup. The committee concurs with DOE’s own finding that “In many cases, long-term stewardship issues were identified, and remedies were proposed, but detailed plans and procedures to effectively carry out the remedies were not developed” (DOE 2001c).

CHIEF RECOMMENDATION

The committee has observed that DOE treats cleanup and LTS as activities to be planned and executed separately. LTS must cope with what is left behind when cleanup ends, but cleanup is shaped by regulations and takes little account of the obligations of stewardship or the likely limitations of LTS.

Recommendation: DOE should explicitly plan for its stewardship responsibilities, taking into account stewardship capabilities, when making cleanup decisions. DOE should also implement steps to anticipate and carry out those responsibilities throughout the cleanup process.13

Remediation encompasses contaminant reduction, contaminant isolation, and continuing care (NRC 2000a).14 In DOE decision-making the first two constitute cleanup, while the last is LTS. In fact, however, all choices about each of these tasks affect the others: Decisions about how much to spend on contaminant reduction or on engineered barriers to isolate remaining hazards need to take into account the capabilities of LTS to prevent harm from residual contamination. This basic consideration is still lacking in the actual implementation of DOE’s remediation program.

Cleanup and LTS are complementary elements of a single task: protecting human health and the environment now and for the long term. Cleanup decisions cannot be decoupled from LTS considerations. As linked elements of a site remedy, they form a

continuum of overlapping choices to be made about long-term management of legacy sites. Choices made before and during cleanup apportion risk and cost across time, as discussed above. Several groups, including this committee’s predecessor and a recent R&D Roadmap team, have provided details on why LTS needs to be considered when establishing cleanup goals and approaches (NRC 2000a; INEEL 2002). They have also provided conceptual models useful for strategic planning, descriptions of limitations in the effectiveness of various LTS measures, and ideas useful in developing implementation plans for LTS.

The committee has found no evidence that DOE (a) is considering requirements for and the likely effectiveness of LTS measures when establishing cleanup goals and approaches, or (b) has worked out practical and enduring means of implementing LTS so as to realize its goals for protection over the long term. In the recent emphasis on accelerated cleanup by DOE, the committee has seen no statement of how DOE will balance that objective against future risks. There is the risk of a need for additional cleanup in the future if remediation is poorly planned or carried out. Moreover, if greater reliance on LTS is chosen over contaminant removal, the consequences and in turn the risks of LTS failures may increase. Explicit consideration of LTS issues when establishing cleanup goals and approaches would demonstrate that DOE is taking its responsibilities seriously—a key step in building trust among wary stakeholders and the wider public, including Congress and state and local governments. The failure to link LTS to cleanup undermines credibility and strengthens the fear among skeptical stakeholders and regulators that a hollow promise of stewardship is being put forward as a substitute for more costly near-term cleanup.

The committee has seen some progress in DOE efforts on LTS. Progress can be seen, for example, in written statements at two sites: Hanford, a large site in Washington state where cleanup is expected to take decades; and Weldon Spring in Missouri, the first medium-sized unit of the DOE complex where long-term stewardship has begun. Both sites have produced LTS planning documents (Hanford 2002; DOE 2002c). These written statements suggest a recognition of LTS, although the documents leave significant questions unanswered.15

A working draft for the Hanford remediation program (Hanford 2002) identifies six LTS program functions,16 with reasonable suggestions for implementation of each. The draft acknowledges that managing remaining contaminants at the site will compete with other priorities (p. 3-1), but there is no articulation of how cleanup and LTS decision making will interact. Managers at Hanford states that they will “work to integrate long-term stewardship concepts into the cleanup decision-making process to ensure consistency and provide opportunities to gain efficiencies” (p. 2-3), but there is no implementation action identified for this objective. Instead, cleanup choices continue to be made without consideration of LTS, and the “starting condition” for LTS (Hanford 2002, Fig. 1-5, p. 1-7) is the residual hazard—even though many choices remain to be made about what that residual hazard should be. The committee also reviewed the “Performance Management Plan for the Accelerated Cleanup of the Hanford Site” (DOE

2002d), a document that spells out substantial changes in the schedule and budget for the Hanford remediation program. LTS is mentioned with little discussion, for example in the statement that “With plans for long-term stewardship integrated into the cleanup, we can take the proper actions at the appropriate time to allow a smooth transition into necessary stewardship activities after the EM cleanup mission is complete” (p ii-iii). There is no mention of the working draft of the site’s own LTS draft report (Hanford 2002). LTS is a critical aspect of remediation at sites like Hanford, where complete cleanup is likely to be impossible. Performance management plans are incomplete when they do not articulate how LTS fits into the decision-making process and when they ignore the criteria or factors that should influence those decisions.

The largest site so far where cleanup has been declared complete, Weldon Spring, was opened to limited public access in the summer of 2002. Management of the site was transferred to DOE’s Grand Junction Office, where its Long-Term Surveillance and Maintenance Program17 resides, even though one of the final regulatory records of decision—the definitive statement that cleanup remedies are in place—remains unsigned.18 Thus, activities that are logically part of cleanup have been shifted into LTS, or placed in a limbo between cleanup and LTS.

This approach may prove innocuous at Weldon Spring, where the ground-water remedy is intended to be natural attenuation combined with active remediation in situ. If the end of cleanup is treated so casually at other sites, however, one might fear that a site like Fernald would enter LTS with neither a place nor a method to send its silo wastes (see Appendix E) for disposal. One might envision similar difficulties with the single-shell tank wastes at Hanford, which have a long and troubled history. In effect, the stewards could be saddled with either cleanup or maintenance problems that are much more hazardous and technically challenging than the program is being equipped to handle. Without proper integration of decisions on clean-up and LTS, there is no mechanism to stop the transfer of inappropriate responsibilities and risks to an LTS program that does not have the resources or capabilities to manage the continuing liabilities. Indeed, clean-up authorities face incentives to do just that.19

Despite statements embracing LTS in recent DOE documents (DOE 2002a, 2002b), the way in which DOE has selected, developed, and implemented remedies means that LTS continues to be an afterthought in practice. Recognizing the interdependent nature of cleanup and LTS would enable DOE, and the many other government agencies facing similar problems, to make better decisions and construct more credible plans for the long term. Adopting this way of thinking about environmental management at legacy waste sites would entail incorporating LTS into every stage of environmental management. This means looking at issues that will be important during the long term in all phases and activities related to the remedy: site investigation, option

development and remedy selection, monitoring, and future adaptation to changing circumstances.20 Each of these is discussed below in the section titled Incorporating LTS into environmental management, following a discussion of how defining DOE’s mission of LTS solely in terms of regulatory compliance is insufficient.

WHAT IS STEWARDSHIP?

DOE uses the term “long-term stewardship” to describe the activities required at contaminated sites where cleanup is “complete” (see Footnote 1), that is, after site closure. As part of LTS, DOE explicitly takes responsibility for complying with all applicable regulations for the environmental management of the site into the indefinite future (see, e.g., DOE 2001b).

The word “stewardship” is resonant in our language and has been readily accepted by many people who have different understandings of the word (see La Porte 2000). In this committee’s view, stewardship comprises several tasks: A steward of very long-lived hazards acts as

-

a guardian, stopping activities that could be dangerous;

-

a watchman for problems as they arise, via monitoring that is effective in design and practice, activating responses and notifying responsible parties as needed;21

-

a land manager, facilitating ecological processes and human use;

-

a repairer of engineered and ecological structures as failures occur and are discovered, as unexpected problems are found, and as re-remediation is needed;

-

an archivist of knowledge and data, to inform the future;

-

an educator to affected communities, renewing memory of the site’s history, hazards, and burdens; and

-

a trustee, assuring the financial wherewithal to accomplish all of the other functions.22

This range of activities requires the human and institutional capacity to fulfill these roles as needed, through the decades and centuries in which the risks persist. The human and institutional demands of these activities are broader than the traditional engineering expertise of DOE, raising questions of how best to meet the federal government’s responsibilities over the long term.

Moreover, a steward does not act in a vacuum. Technological capabilities are likely to change. Study of monitoring data and the accumulating experience of stewards is likely to improve both understanding of the sites and of how to manage them effectively. Both sets of changes will likely prompt reappraisal of risks and consideration of additional remediation. The likelihood of such development implies a responsibility for stewardship at the national level, in addition to the site-centered roles listed above. The committee calls for a national dialogue at the end of this report, in part to articulate these programmatic responsibilities so that they may be taken up in a sensible fashion.

Beyond a Compliance Culture

LTS begins with a recognition of the dimensions of the long-term obligations of the legacy wastes. DOE’s actions observed by the committee do not yet reflect such an understanding. Instead, the committee has seen a more narrow focus on meeting compliance agreements and regulations, as if DOE’s responsibilities were grounded only in these: Regulators agree to a remedy, creating a compliance agreement, and the requirement of LTS is that DOE sustain the remedy. Compliance is necessary, of course, but the problem with a strict reliance on compliance is that today’s regulations do not fully address LTS challenges.23

Under its agreements with state and federal regulators, DOE undertakes to manage the residual contamination at the legacy waste sites; compliance with those agreements is a means to that end. Yet the regulations on which the agreements rest do not engage all of the difficult issues presented by the legacy wastes. This is so even though the long-term effectiveness and permanence of a remedy is one of the criteria to be used in remedy selection under CERCLA,24 the law that frames decision making for

|

|

compensate people who are found to have legitimate claims of injury is a complex issue that the committee has not explored. |

many of DOE’s cleanups. This formal criterion has not resulted in thorough examinations of stewardship so far, nor even of the specific institutional controls stipulated in regulatory documents. On the contrary, regulators have agreed to remedies at DOE sites with only scant provisions for LTS, not considering in some cases the risks of LTS failures, leaving the functions of trustee, educator, and land manager unaddressed, and assuming that institutional controls are self-executing and self-enforcing. CERCLA provides for recurring reviews at five-year intervals for closed sites that do not meet criteria for unrestricted use, but the extent of that obligation and the effectiveness of the review program are as yet uncertain. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) governs many of the DOE facilities and cleanups that CERCLA does not, and RCRA’s requirements do not take a long or broad view with respect to LTS.25 Experience with institutional controls demonstrates their limitations and fallibility, particularly over the long term (Applegate and Dycus 1998; ELI 1995; Pendergrass 1996, 1999, 2000). The point is not that institutional controls should not be used; they are among the few tools available. But their fallibility and the uncertainties that surround many engineered containment methods mean that simply assuming that compliance conditions will continue into the future (e.g., land-use controls administered by elected local officials), is not likely to provide long-term protection of humans and the environment.

To address the long-term aspect of LTS, DOE staff (Geiser 2002) has advanced the concept of rolling stewardship. Rolling stewardship means a succession of stewards tending to needs, one generation after another.26 DOE’s Site Transition Framework (DOE 2002b) is a step in the direction of rolling stewardship, identifying documents that should be passed to new site owners or stewards. It is, however, only a checklist—it helps to ensure that a document is passed, not that the document contains what it should, or even that the relevant underlying information is available and accessible. DOE relies on external regulatory mechanisms—that is oversight by state and federal regulators—to ensure that needed data are provided.

Current regulations do not directly address LTS, as defined by the committee or by DOE. It is possible that requirements to take many of the actions the committee recommends and fulfill the needed roles could be seen as compatible with current regulations (particularly using the criteria for remedy selection under CERCLA), but most requirements are not spelled out in the regulations. Regulators have neither interpreted broader LTS requirements as implicit in the regulations nor been demanding in enforcement of the LTS aspects of even those that are specifically listed. Furthermore, DOE (like all federal entities) refuses to accept any land-use restrictions imposed under state law (e.g., Colorado’s environmental covenants law) on property owned by the federal government.

Such a compliance-driven approach encourages a view of LTS as little more than routine monitoring, maintenance, and record-keeping. That view rests on a bold assumption: that the U.S. government will endure in essentially its current form into the indefinite future. This may not be a prudent basis on which to embrace a responsibility projected to last far longer than the history of the republic so far. DOE bears an enduring responsibility—and a corresponding liability—for problems that arise in the future at its legacy waste sites. It is in the long-term interest of

DOE and the nation for DOE to recognize and act to fulfill its obligations, even when they carry the agency beyond existing regulations. As the committee explains below, for a public agency to act in this fashion responsibly requires explicit attention to the values at stake in making choices and committing resources.

INCORPORATING LTS INTO ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT

Here the committee offers its view of what it means to incorporate LTS considerations throughout the remediation process (site investigation, option development and remedy selection, monitoring, and future adaptation to changing circumstances), emphasizing factors that go beyond a compliance-driven engineering approach. Such an alternative approach raises questions that are fundamental as well as practical, so questions are woven throughout the discussions of each part of the remediation process. The questions are framed deliberately as open-ended concerns, because in many cases the committee can offer only limited strategies and recommendations to address the questions and challenges DOE faces.

Two broad questions, discussed here and toward the end of the report, are fundamental to all of DOE’s remediation efforts.

Question: Can DOE develop a coherent set of guiding principles for making choices among the burdens to be borne by present and future generations in addressing enduring risks, and would application of such a set of principles result in better, more defensible decisions?

The process of remediation makes value commitments—apportioning costs and risks over time, among populations, and altering the environment and the hazards posed. These values are expressed through decisions that are influenced by the state of the site and its surroundings, scientific understanding, and technological and institutional capabilities. The committee has not seen the values entering into DOE’s decisions

articulated in a way that connects to the people affected (in both present and future), or to human obligations for care of natural systems. Without clearly articulated value premises, DOE lacks a basis on which to defend its decisions (Russell 2002), except by complying with regulations that were written without regard to the long-term demands of legacy waste sites that will require LTS.

Question: How can DOE carry out its mission of environmental management in such a way that when people learn more about DOE’s activities, they are likely to gain confidence in the institution and its actions?

In pursuing its unprecedented responsibilities of remediation, DOE needs public trust if the agency is to have sufficient flexibility to reach its cleanup objectives and to begin LTS. As the magnitude of its waste-management problem has become more widely appreciated, DOE has labored under a deficit of public trust and confidence (DOE 1993). There has been significant progress in gaining trust as DOE shared information and worked with stakeholders; the committee found this in its site visits. Yet difficulties remain (see, for example, the mistrust evident in written exchanges concerning Weldon Spring [Mahfoud 2002]). Trust is essential if DOE is to undertake negotiations and sound decision making regarding cleanup and LTS. The stewardship relationship “rests significantly on the underlying strength of trust in the person[s] involved” (La Porte 2000),27 and much of DOE’s efforts will depend on public confidence in the capabilities and continuity of those speaking for the institutions undertaking this unprecedented commitment. As discussed below, building and maintaining trust requires continued support for changes in organizational culture at all levels of DOE and its contractors.

The work of stewardship will require candor in acknowledging knowledge gaps, followed by sustained learning from experience over the coming decades as DOE proceeds with cleanup and maintenance of its legacy sites. The committee is not, however, a management consultant, and the questions and recommendations below emphasize natural and social science and technology, rather than managerial tools. The assistance that the committee is able to provide on these questions has been limited by the truncation of the study.

Each of the following subsections examines ways in which DOE could incorporate LTS into environmental management. Some of these ideas have also been brought up by other advisory bodies. The subsections address planning for changing environments, working with stakeholders, factoring LTS into decisions about cleanups and end states, and planning for fallibility, monitoring, and institutional challenges.

Planning For Changing Environments

Stasis is a standard engineering goal of environmental remediation, as currently conceived: keeping containment structures intact and design features unchanged (consider, for example, a dam or a waste cell). But ecological settings are dynamic rather than static, and change in natural community structure is often a sign of environmental health, as a habitat develops. Each LTS site is embedded in a dynamic

landscape. This change can be seen in the local ecological community, in the physical environment, and in society’s needs and pressure on the site. Physical and institutional controls must be designed for and adapt to the landscape if they are to survive the long time horizons for which they will have to be effective.

Question: How can DOE identify paths of ecological change for each LTS site, and how can DOE design for and accommodate change with resilient engineered solutions?

At the Moab and Fernald sites, the land surface is now designed for near-term soil and slope stability, using a narrow palette of plantings to prevent soil erosion. A cover engineered in this fashion is not a substrate that can support a healthy natural community over time. Nor is it likely to remain in the engineered form for long without extensive management and care. The kind of prairie landscape envisioned for Fernald, for example, will require weeding to eliminate the larger plants and trees that are natural to the area. Moreover, a responsible design must consider the natural community that is likely to emerge. One of the few biotic concerns that is mentioned in current LTS documents is rare and endangered species, but these are uncommonly found at legacy waste sites, almost by definition. All sites, however, have locally common species, or will have them soon. Encouraging their presence by initiating populations and designing engineered structures to meet the basic habitat needs of locally common species allows the site to function ecologically over a long time period. This can be done so that ecological change will be more likely to reinforce engineered barriers, rather than undermine them. At the same time, engineered barriers must be designed with both the health of local biota and also the likely interactions between local biota and the barrier in mind.

Many geological processes take place slowly over years to hundreds of thousands of years (e.g., weathering) or even longer, whereas others are infrequent, unfold rapidly at unpredictable intervals, and are sometimes of sufficient magnitude to alter landscapes (e.g., floods). Both kinds of process are important influences on hazards that persist over long time scales (see NRC 2002a). Some of these processes are readily mitigated by engineered barriers and preventive actions, while others will proceed without significant human intervention, leaving stewards to react. Current regulations are written for time periods where historical experience provides a baseline of institutional experience; as a result, slow geological change is ignored and simplified analyses are used to bound stochastic change.28 The aim in remedy design must instead work toward remedies that are resilient to slow change, as well as toward ways to maintain response capabilities to react to sudden disturbances. For example, DOE might choose permanent relocation of hazardous materials away from threatening erosional forces, if the risks of erosion warrant concern. Where relocation is deemed not to be feasible or appropriate, mitigative measures and some funding mechanism could be established to respond to major failures.

Human activity, too, is dynamic. Land use can undergo rapid changes, as illustrated by the recent encroachment of residential communities toward Rocky Flats and by the commercial growth of ecotourism in Moab. Some sites that once were little known and remote are being affected by the growth of nearby cities and towns, with

attendant pressures for development of land, use of water, and alternatives for employment. These historically rapid changes, which often have no precedent at a site, limit the reliability of institutional controls.

Finally, it is worth noting that scientific understanding is changing. In the 20th century, environmental regulations supplemented or superseded the older law of nuisance with demands for ways of anticipating and preventing pollution. This new approach was adopted in response to growing scientific and technological capabilities both to understand and to affect our environment (Rodgers 1994). Similarly, the realization that legacy sites cannot be cleaned up completely is stimulating research and innovation that is likely to strengthen the technical and institutional bases of LTS in the future. Thus, LTS measures themselves need to be adaptable.

Recommendation: Design and select remedies that accommodate or benefit from natural communities and processes, so as to enhance durability of the remedies.

Involving The Local Community

As noted in this committee’s report on the Moab Site (NRC 2002a), decisions that involve risk management should involve the stakeholders from the earliest phases of defining the problem through the making of binding decisions.29 Such involvement is an important element of risk analysis and characterization (NRC 1996b; Sandman et al. 1993) and also tends to foster public trust and confidence in the institutions that analyze and characterize risk.

Question: How can DOE develop and manage LTS measures in partnership with the stakeholders who will bear the impacts of their failure and who may be willing to share with DOE responsibility for their implementation?

Site remediation aims to improve the environmental circumstances of local communities. Remediation often entails significant changes, however, and for this reason members of the community often have interests to advance or defend. Yet the community as a whole can also add value to the decision-making process in the following ways and for the following reasons (see Susskind and Field 1996; Sandman 1994):

-

they often have relevant information (e.g., about past activities on-site, about desirable or potential future uses of the site);

-

they often have creative solution options, including alternatives difficult for a federal agency to propose or develop;

-

they may have institutional capabilities to undertake cleanup or LTS activities, including ones unavailable to a federal agency or available at a much lower cost; and

-

their values must be a factor in any responsible effort to balance costs, benefits, and risks, both as a matter of right and because they have political power to make the process easy or difficult for DOE.

In a democracy, the local community also has a right to know what remediation measures will have been taken, what are the risks of failure for both the remedy and LTS, and what contingencies have been provided (Applegate 1998a).

At all three sites the committee visited, stakeholders asserted that they were willing to share some of the responsibility for implementing LTS measures with DOE, a noteworthy similarity across sites varying widely in other respects.

To the extent that local communities or other non-DOE stewards are to exercise stewardship responsibilities, adequate resources (information, expertise, and funding) must be assured, and DOE would be prudent to confirm that other stewards have the capacity to fulfill the LTS functions they seek to assume.30

Work by Susskind (see, e.g., Susskind and Field 1996), Sandman (Sandman et al. 1993; Sandman 1994), and others on public participation in planning and decision making emphasizes lessons learned from site-specific environmental controversies over the past generation. The committee’s site visits reinforced these lessons, which are distilled into the recommendation below.

Recommendation: DOE should foster a positive working relationship with interested parties to work together to achieve common goals of protecting human health and the environment. DOE can foster such relationships by the following actions: (1) explicitly acknowledge the nature and extent of its stewardship responsibilities, (2) help to frame the issues and uncertainties of stewardship for the public, (3) inform and educate the public on the options, constraints, and other factors influencing its own decision-making, expanding on what DOE has done with respect to clean-up; (4) solicit ideas and information from the public on these questions, (5) work with the public toward mutually agreeable decisions, where possible. All of this requires that DOE have a coherent model for framing the values at stake in stewardship and for incorporating views on the nature of the risks and the uncertainties, as discussed above.

Developing And Selecting A Remedy

DOE’s current practice at the sites examined by the committee aims at remediating a site enough to secure agreement on a record of decision (ROD) for site closure. Because current regulations do not capture all of DOE’s responsibilities, as discussed above, the DOE’s practice ignores factors important to LTS.

The legacy wastes are the permanent responsibility of the U.S. government, a fact reflected incompletely in the regulatory structure within which DOE operates. (EPA is beginning to spell out detailed requirements, but these efforts are still incomplete.) In principle, decision making must

-

identify and describe each cleanup option, assessing its features under normal functioning and failure scenarios. These features include the health and ecological risks averted and incurred, costs (including opportunity costs), and cultural and aesthetic impacts;

-

assess how people view the features of these options;

-

identify and describe associated stewardship requirements (including long-term monitoring, re-remediation in the case of failure or advances in technology, institutional controls, maintenance of records, and public education);

-

assess the feasibility of each cleanup option and its associated stewardship requirements, including technical feasibility, institutional feasibility,31 and cost; and

-

make choices taking into account the information developed during this process about both near-term cleanup and LTS.

Those developing the remedies at sites will need to decide to go through these decision-making steps, and they will need the time to go through the process. In the case of the Moab Site, the legislation passing responsibility for the abandoned uranium mill site to DOE mandated choices before there was time for an adequate site characterization, and indeed DOE has since found unexpected contamination of soil, particularly in the cover material on the pile. In addition, the local community’s willingness to be part of a solution that encompasses both cleanup and stewardship lay outside the planned scope of decision. At other sites, the committee saw cleanup decisions made without adequate understanding or consideration of LTS. As mentioned above, the recent emphasis on early closure needs to be accompanied by an equally strong mandate for quality in planning and operations for the long term, with full accounting for the resources and institutions required for continuing success—including provision for possible additional cleanup in the future.

At both Mound and Fernald, where cleanup is well advanced, site characterization efforts had overlooked potentially significant interactions between the site and its surroundings. For example, at Mound, proper understanding of how an underlying bedrock system might hydraulically connect the site with surrounding areas appeared to be lacking. At Fernald, interactions between the site and an adjacent contaminated site where pump-and-treat remediation was being proposed had not been considered. Understanding potential interactions between a site and its surroundings is key to predicting long-term contaminant behavior at a site and designing sensible monitoring programs. Yet, in these two locations such interactions had not been taken into account.

Protecting public health is the chief objective of cleanup and LTS. In addition to its intrinsic value, the health of people in communities surrounding DOE legacy waste sites and of people working on or near those sites is a potential indicator of contaminant or radiation exposures. Their health could be monitored. The committee has not examined public health activities and research at DOE sites, but was considering how plans to monitor the health of local communities, and specifically people who interact with the site, could be incorporated as part of the surveillance needed for LTS.

Question: How can DOE incorporate the evolving understanding of the requirements, likely capabilities, and limitations of LTS into choices about targets and end states of cleanup at DOE sites?

Explicitly considering LTS issues when making cleanup decisions entails asking what is at risk, and how important is it? What are our capabilities for LTS with respect to what is at risk? How do these fit with our capabilities for cleanup? How might all these change over time? These all lead to the summary question whose answer depends on the above, what is the appropriate mix of cleanup and LTS? Asking and addressing these questions closes the loop on remedy development and selection, recognizing that LTS is an essential part of the remedy and not an afterthought. In addition, by openly discussing LTS, DOE can build trust as it carries out cleanup, strengthening the understanding and support for LTS when stewardship begins.

The institutional components of LTS are discussed at the end of this report, but here it is important to point out that the institutional aspects of remediation need to be analyzed with other elements of a remedy, taking into account the capabilities and limitations of institutional controls (Applegate and Dycus 1998; ELI 1995; Pendergrass 1996,1999, 2000). Unfortunately, while DOE has devoted substantial resources to research into such matters as how to assure that concrete barriers surrounding wastes will endure, DOE has devoted little effort to the design of and provision for institutional controls, on which long-term protection of health and environment will depend. Suggestions for remedying this failure are discussed below.

Planning For Fallibility

Unforeseen events will occur at DOE’s legacy waste sites. These events might include failure of a remedy to prevent degradation of a waste cell, a concern at the Moab Site (NRC 2002a); the failure of remedies to meet prescribed cleanup or containment

goals; discovery of “unexpected” contamination (NRC 1997, 2000b);32 or unintended use of the land by humans, animals, or plants. LTS at each site is unavoidably a complex system made up of interactions among engineered environments, natural environments, and human institutions, which makes them somewhat unpredictable.33 At each site the committee visited, the committee saw little consideration of the question “what are the consequences if controls fail?” “Plan for fallibility” was a principal recommendation of this committee’s predecessor (NRC 2000a).

Question: What are the consequences of LTS failures at DOE’s sites?

DOE appears to have considered only the intended future land uses at Mound and Fernald in its assessments of risks in the future. Yet institutional controls have sometimes failed, endangering public health and environmental quality.34 When asked to describe the risks if unintended uses (specifically, residential uses) were to emerge at these sites despite prohibitions, however, DOE was unable to provide an answer at any of the sites the committee visited, because only the intended uses had been examined.

The probability and harms associated with failures must be factored into decisions about the scope, extent, redundancy, and diversity of controls and other LTS provisions. All risks are not created equal. A failure of one type could result in an increase in human health risk that, while undesirable, is not catastrophic. Construction of residences on parts of Fernald designated to be held as open space might be an example of this category of risk, while excavation and use of the mill tailings at Moab for building material could lead to more significant exposures. These factors must be considered when determining the level of assurance sought in decision making. Some have provocatively asked, “Does anyone actually think that people are going to die at these sites?” The answer must be that we do not know if people will die as a result of contaminants at these sites, because the analyses have not been done.

There is another kind of uncertainty: programmatic risk. Suppose the selected remedial actions are implemented as planned, but fail to achieve their goals? The committee observed scant recognition or consideration of this possibility, which is salient with respect to the cleanup of ground water. Several analyses (NRC 1994, 1997, 2000b) have concluded that pump-and-treat remedies for ground-water contamination may be much less successful than hoped. Pump and treat can provide adequate containment of the dissolved contaminant plume if the pumping strategy is designed and operated to provide hydraulic capture of the plume. Yet containment may fail to achieve site cleanup in any reasonable time frame when sufficient contaminant mass is not removed. As a result, contaminant rebound has been noted at numerous CERCLA sites once pumping is terminated (NRC 1994); in these situations, pump-and-treat systems may have to be

maintained indefinitely. Failure of pump-and-treat to achieve cleanup is especially likely if the site has a mixture of radioactive contaminants and organic chemicals (e.g., chlorinated solvents or fuels). Alternatives to pump-and-treat can be considered at some sites, but at others, recognition has to be given to the fact that hazards may endure in ground water for periods far longer than originally intended.

Guidance for doing risk assessments for contaminated sites is reasonably mature, but estimates of risks far into the future inevitably become progressively less certain. Methods for assessing risks from the failure of waste containment cells are not consistent or well developed. U.S. EPA, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (U.S. NRC), and different sites within DOE have different approaches for assessing risks of failure of engineered barriers, and it would be worthwhile to develop a method to characterize the various approaches and to seek consensus on best practices.

Recommendation: Plan for fallibility. Conduct failure analyses to inform decisions. Seek consensus on best practices in risk analysis for failure of disposal cells.

Planning for fallibility is a central component of earning trust. Acknowledging fallibility builds credibility. Planning for fallibility entails considering in decision making the consequences of failures of institutional and engineered controls, and designing robust mechanisms to respond to such failures.

Monitoring

Monitoring is an essential part of LTS. It provides the mechanisms for detecting anticipated possible failures, detecting unanticipated events, and evaluating the effectiveness of remedial actions. Monitoring is also essential to learning as LTS proceeds. Monitoring cannot be de-coupled from an understanding of the design decisions that were made at sites: for example, failure detection requires a quantitative understanding of the acceptable bounds of system behavior. Thus, an important challenge of a durable monitoring program will be transfer of knowledge, and not simply data, to successive generations of stewards in a way that supports the mission.

Monitoring must be tailored to the characteristics of a site and its residual contaminants; the variables to monitor, as well as protocols for measurement, need to reflect the site and the risks it poses, for both practical and economic reasons. There is enormous variation across the legacy sites within the DOE complex, but that does not mean that each site should have its own scheme for reporting and retrieving monitoring data—just the reverse is true. A shared framework for reporting monitoring data is essential to assure that the information is preserved and useful. Comparisons among sites, so as to detect failures and problems, will be difficult or impossible without monitoring data that can be compared. It is also important to preserve accessibility of electronic records, since many forms of technical information, such as simulation models and geographic information systems, can only be read in electronic form. The tools for reading such data, together with the formats used to encode them, have been changing rapidly over the past two decades, and it is unclear that durable standards will evolve soon. The distinction between monitoring, which reflects the characteristics of the site, and reporting, which reflects the enduring national responsibility for LTS, must be reflected in policies, budgets, and practices. The committee saw evidence at each of the

sites studied that these issues were recognized, but national guidance is lacking, so that the process of implementation is undermining consistent, retrievable reporting of monitoring.

Recommendation: DOE should tailor its monitoring to the specific risks and circumstances of its sites, while at the same time providing national-level guidance for reporting formats and record-preservation protocols.

Institutional Challenges—Trust, Constancy, Learning

Long-term management of the legacy wastes remaining after cleanup will be shaped by two precarious societal conditions: trust in implementing institutions, and confidence that those institutions will exercise stewardship satisfactorily over many generations. In addition, the technological and organizational means to implement LTS are still being developed as sites reach closure. DOE accordingly needs to learn from this experience. These are significant challenges, but there is some relevant experience in the operation of high-reliability organizations as well as in the management of natural resources. High-reliability organizational tasks, such as air-traffic control, require high levels of trust, both within the operating organization and in its social environment. A central finding of studies of high-reliability organizations is that public confidence reflects the way in which the operations of an organization are carried out. In the present context, this means that how planning and cleanup are carried out shapes the confidence the public, stakeholders, and political leadership will place in DOE as cleanup ends. Not only is the substance of LTS affected by choices made in the cleanup process, but so is the social setting in which LTS will be conducted. That setting is critically important to the ability of the steward to discharge its responsibilities. Thus, a question posed at the beginning of the section on incorporating LTS into environmental management is restated here.

Question: How can DOE carry out its mission of environmental management in such a way that when people learn more about DOE’s activities, they are likely to gain confidence in the institution and its actions?

Trust and constancy

The confidence level of stakeholders and the public—their trust in DOE—bears a direct relationship to the latitude, resources, and esteem afforded to, or withheld from, the agency. If there is a surplus of trust in implementing organizations, leaders are likely to have a good deal of discretion, adequate resources, and considerable esteem, resulting in technological autonomy. If, however, the implementing institutions face a deficit of public trust and confidence, conflict is likely to rise (even over technical issues), regulatory constraints can multiply, and resources can become more difficult to obtain.

The greater the deficit the more institutional leaders are pressed to recover it. Where there is a great deficit, some argue that recapturing trust may be impossible (Slovic 1993). Sidebar 1 summarizes means of maintaining and rebuilding trust. The essentially permanent responsibility of LTS and the inherent uncertainties involved make it especially challenging to cultivate trust in institutions implementing LTS. The longer a project, and the more generations of managerial leadership required, the greater the

|

SIDEBAR 1 MEANS OF MAINTAINING AND ENHANCING TRUST Interaction with External Parties

Internal Organizational Conditions

Sources: La Porte and Metlay (1996), DOE (1993), La Porte (2001). |

|

SIDEBAR 2 CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH INSTITUTIONAL CONSTANCY Assurance of Steadfast Political Will

Organizational Infrastructure of Constancy

Sources: La Porte and Keller (1996), La Porte (2000, 2001). |

likelihood of a loss of institutional memory and diffusion of commitment—and the greater the need for institutional constancy. No formal human institution has endured as long as the projected life of some of these hazards. Institutional constancy entails organizational perseverance and faithful adherence to the mission and its imperatives over long time periods. The goal of constancy is to give confidence that organizations will keep their word from one management generation to another. Characteristics of institutional constancy are listed in Sidebar 2 (La Porte and Keller, 1996). A deficit of trust and limited assurance of institutional constancy make implementing LTS arduous under the best of circumstances, given industrial societies' practice of discarding most materials as wastes. It is therefore important for institutions and their leaders to tackle the deficit of trust openly.

Learning

Even under an accelerated schedule, active remediation of DOE’s legacy waste sites will last for decades and involve activities at more than 100 locations in different geographic settings. As cleanup concludes at each site, the resources flowing in from DOE are expected to decline substantially, not only in funding but also in the technical expertise on-site, and in the information produced by a declining profile of activity. The diversity of sites and length of time that cleanup will take both provide useful opportunities for learning from experience, strengthening the knowledge base for LTS.35

Reduced resource flows also mean that stewardship will unfold in a far different social and political environment than today’s cleanup program. What is unclear, in light of the problem of trust and constancy, is whether a different social setting will make LTS harder or easier than is currently anticipated.

Ground-water cleanup is expected to continue at most sites for a long period after they enter LTS, because of the slow pace at which subsurface contamination can be treated. The decades-long duration of ground-water operations means that DOE will be tending the site, and monitoring containment long enough that DOE will enact rolling stewardship before the remedial actions are complete. This provides a time period in which to build trust and to test institutional constancy, while gaining experience with containment measures.

A study panel of the National Research Council (NRC 2003b) recently recommended to the U.S. Navy an approach to conducting its ground-water cleanup so as to improve its understanding of the hydrogeological behavior of contaminated sites. The primary innovation is to use a conceptual site model to bring together the technical and institutional understanding of the site and the environment of its surrounding land and water. The conceptual site model creates a framework for selecting monitoring locations and protocols, together with expected values of contaminants and other environmental indicators over time. The conceptual site model is expected to be incorrect, because predictions of site behavior are based upon incomplete understanding. But as cleanup proceeds and land use and other conditions change, the conceptual site model can be updated and corrected by the monitoring process. In essence, this is a way of incorporating learning into management by making development of understanding and adaptation to change an explicit core component of the mission. In this approach, known as adaptive management (Holling 1978; Walters 1986; Lee 1993), surprise is expected and surveillance yields improved understanding. Adaptive staging, a related idea advanced by another National Research Council committee (NRC 2003a), could serve as a model for thinking about these issues with respect to management of long-term hazards, especially for cleanups that will take a long time.

As the committee argues above, regulations do not provide adequate guidance on the risks to be managed in the long term. An adaptive approach, using a conceptual

site model, provides an explicit set of understandings and predictions, which can, in turn, frame a discussion among DOE, regulators, and stakeholders on how to go beyond the existing regulations in protecting the site and affected populations and habitats.

Recommendation: During ground water remediation, rolling stewardship should become explicitly adaptive, adopting learning as an explicit objective. This can serve as a pilot effort for incorporating learning into all elements of LTS. Use of an adaptive management framework, such as a conceptual site model, should be explored as a means of organizing learning at the DOE legacy sites.

At the national level, this means that the experiences of sites in different political jurisdictions should be studied, with the aim of assuring that the variations in performance are due to differences in local environmental conditions, rather than differences in the capacities of local managers and institutions. A process with some parallels (not all reassuring) is the periodic re-accreditation of colleges and universities to provide assurance of national quality control while permitting substantial autonomy and variation.

It is important to note that adaptive management of natural resources has not been successfully implemented (Lee 1999). Although it is technically straightforward, adaptive management has encountered institutional difficulties, rooted in the reality that managers are reluctant to be proven wrong—even when correcting understanding that is known to be incomplete is a stated mission. If DOE wishes to build trust and a reputation for constancy, however, it is timely for the Department to admit something that is obvious to all observers of radioactive waste management: The task is difficult and understanding is incomplete. Paradoxically, building trust is a strong reason to admit the possibility of errors and to seek open ways of recognizing error and improving understanding going forward.

Recommendation: DOE should build understanding during the remaining period of cleanup, so as to make LTS a welcome step as sites are closed. Activities during the ground-water cleanup phase provide important opportunities to build credibility.

In its work the committee has come to appreciate the substantial gaps in the nation’s organizational, operational, and social understanding of how to manage the hazardous residues of industrial economies over very long periods of time. Addressing these gaps will be critical to long-term institutional management, and social science research should be carried out as an integral component of research and development in waste management.

Other reports (INEEL 2002; NRC 2000a) have called for case studies and comparisons among sites to bring together the lessons of past experience (NRC 2002a). In the decades to come, as cleanup proceeds, it is also worthwhile investing in social science studies that can improve trust, constancy, and learning. In particular, the characteristics of high-reliability organizations are related to trust and constancy (La Porte 2001), and the continuing efforts to improve the ability of organizations to learn in the face of uncertainty (Walters and Holling 1990; Lee 1999) are priorities to be considered.

ALLOCATING RISKS & COSTS WITHIN AND ACROSS GENERATIONS: A NATIONAL DIALOGUE

At any given point in time, each DOE site imposes a mix of risks, costs to maintain the risk within acceptable levels, and uncertainty as to future risks and costs (Russell 2002). Consequently, each decision at the site incorporates compromises and tradeoffs among these factors, and should reflect and implement societal values concerning each. Long-term costs, liabilities, and benefits are difficult to take into account: Their estimates are inherently uncertain, and there is no consensus on how to value their consequences and translate those as a guide to current decisions (see e.g., Portney and Weyant 1999 and NAPA 1997).36 Yet DOE’s cleanup program cannot entirely eliminate the risks; the program only alters the mix of risk and costs to be borne at different places and times. As noted near the beginning of this report, all remediation decisions are choices that affect that mix and what burden is borne in cleanup and in long-term stewardship. Thus, DOE has been making decisions that affect the well-being of this and future generations, usually without recognizing that fact or explicitly weighing its implications.

Many of these decisions will have consequences that are costly to reverse— materials may be moved or barriers may be built to immobilize contaminants, property may change hands, and other steps may be taken that would be difficult or impossible to undo. In particular, choices made in the past have created responsibilities that endure, such as the decisions made to precipitate liquid wastes in the Hanford tanks, which created solidified materials that are difficult and expensive to deal with (see, e.g., Gerber 1992). For this reason, a deliberate and transparent decision-making process is needed to spell out the implications of remediation decisions for risks and costs in the future. Those implications go beyond expectations of technical outcomes and include how those outcomes will be valued in an individual and societal context.

Sharing the Burden: The DOE Cleanup Program is not alone in needing LTS

As noted earlier in this report, without a coherent set of guiding principles for making choices among the burdens to be borne by present and future generations in addressing enduring risks, DOE’s decisions will continue to be made ad hoc and will remain difficult to justify. DOE is the nation’s agent in these decisions on allocations of risks and costs within and across generations, and needs guidance on how to make them.

That some sites contaminated by industrial activities cannot be completely cleaned up is still being recognized by landowners and governments responsible for safety, health, and environment. When the predecessor to this committee issued its report in the year 2000, the primary finding regarded as newsworthy by the American press was the sheer number of contaminated sites in the DOE complex that would require LTS. There are many other sites that are also likely to remain contaminated, mostly with chemical toxins, in this and other nations.

The management of potentially hazardous sites over extended periods of time is a burden shared by many federal agencies. While DOE’s approach to this issue is the focus of this study, the responsibility of DOE for its legacy sites bears strong similarity to EPA’s responsibility for closed Superfund sites or hazardous waste landfills, DOD’s responsibilities for its former and present facilities, the Department of Interior’s responsibilities at thousands of sites including abandoned mines, and states’ responsibilities at “brownfield” sites that are not on the National Priorities List. In the CERCLA program alone, over 600 sites include institutional controls in their RODs (U.S. EPA 2001). The federal government has hundreds of complex, multicontaminant sites, which are difficult to clean up. It therefore makes sense to approach them in a coherent fashion. Similarly, while the goal is preservation of the good rather than protection from the bad, the National Park Service and National Wildlife Refuge System face open-ended responsibilities that also fall within a common notion of stewardship.

These are national issues, they involve deeply held values, and they have substantial consequences for present and future generations. In short, they demand and deserve broad public discussion. Instead, however, they have been treated mostly as technical issues with only parochial attention paid to the values that are involved. The beginning point for resolving these issues and providing DOE and other agencies with the guidance they need would be a public dialogue to inform and engage people in a process that allows their values to be expressed and heard. Reaching resolution may well require national leadership. DOE and the other affected agencies can take responsibility for initiating such a dialogue, perhaps by making the implicit value predicates of their decisions apparent and requesting comment. They are the bodies that are both most knowledgeable and most directly involved in these issues.

Subsequently, of course, the criteria and methods for decision-making for such situations would need to be devised. To the extent that DOE sites are comparable to those of other federal agencies, a coordinated effort across agencies could help develop systematic methods for addressing such decisions. Within DOE, generic problems such as long-term site management have been the subject of programmatic environmental impact statements. A similar interagency process could lead to the implementation of methods that gain general public acceptance. Such a broad national approach could also lead to better interagency coordination to improve stewardship.

An effort is underway to develop a memorandum of understanding on LTS at federal facilities among the Environmental Council of the States, DOE, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Interior, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The purpose is to provide a basis for discussion and coordination on LTS issues by establishing shared principles for LTS and seeking agreement on how LTS fits into the remedy process, what LTS goals are, what is expected from LTS, who is responsible for fulfilling LTS functions, and what is needed to support them.37 This is a commendable step toward the kind of national dialogue that the committee recommends.

The legacy wastes pose an unfamiliar and difficult challenge to society and to DOE. Sites that cannot be cleaned up enough to permit unrestricted access remain

hostage to technology and organization. Engineered barriers may fail; ground-water cleanup may not succeed; most of all, organizations comprised of human beings need to remember, monitor, and respond when problems are discovered. Humans are fallible, a frailty inherited by organizations. This is the legacy that matters most. Stewardship of religious, educational, and civic institutions has succeeded for centuries, and in a few cases for longer. Stewardship has succeeded when people have sustained their attention and capacity in the face of adversity and distraction. Long-term stewardship of the legacy sites needs to be taken into account at all stages of remediation, not only because LTS is an important social goal, but because it tests society’s diligence to an unusual degree.

DOE managers today stand at the starting point of a journey. Future generations will need to find their own way with the legacy waste sites. What the current generation needs to do is to make its choices about cleanup and LTS in ways that will give future generations the knowledge and resources to make their choices responsibly. DOE is choosing a course on which to embark and a vessel in which to sail.