1

INTRODUCTION

Seat belts have proved to be one of the most effective safeguards against death and injury in a vehicle crash (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48). Efforts to encourage seat belt use span 30 years, yet in 2002 approximately one-quarter of U.S. drivers and front-seat passengers were still observed not to be buckled up (Glassbrenner 2002). The number was considerably higher for drivers with a high risk of crash involvement; nearly 60 percent of drivers in high-speed fatal crashes were unrestrained despite the fact that drivers and passengers can reduce their risk of dying in a crash nearly by half simply by buckling up (O’Neill 2001). U.S. belt use rates are substantially lower than in many other industrialized nations. Canada, many northern European countries, and Australia can document belt use rates that exceed 90 percent (O’Neill 2001).

Making further gains in U.S. belt use poses a considerable challenge. The proven safety benefits, better design, and especially laws combined with aggressive enforcement have contributed to increased belt use. Nevertheless, on average, one in four drivers and passengers continues to ride unbuckled. Consequently, technological approaches for changing motorists’ behavior are currently being explored. In legislation passed in December 2001, Congress requested that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) contract with the Transportation Research Board to undertake a study to consider whether newly developed vehicle technologies may present opportunities for increasing seat belt use without being overly intrusive.1

The study charge comprises three tasks:

-

Examine the potential benefits of technologies designed to increase belt use,

-

Determine how drivers view the acceptability of the technologies, and

-

Consider whether legislative or regulatory actions are necessary to enable their installation on passenger vehicles.

|

1 |

The request was contained in Conference Report 107-308 to accompany Appropriations for the Department of Transportation and Related Agencies for fiscal year 2002, June 22, 2001 (see Appendix A). |

The scope of the study is further limited in the following ways. First, the congressional request is focused on passenger vehicles only, which include cars and light-duty trucks driven for personal use (i.e., sport utility vehicles, vans, and pickup trucks). Second, the focus is on technologies in new vehicles and new car buyers, although aftermarket devices are considered. This has implications for belt use gains because many new car drivers already buckle up (Williams et al. 2002, 295). Third, issues of belt comfort and convenience and perceived effectiveness are considered as factors affecting belt use. However, belt design is considered to be outside the study scope. Finally, although the study committee recognized the wide range of other strategies for increasing belt use, it did not attempt to analyze them in any depth. Congressional interest in this study is focused on an assessment of the potential for technology to increase seat belt use and the extent to which federal laws and regulations pertaining to these technologies may inhibit their introduction.

SEAT BELT EFFECTIVENESS

Use of seat belts is the single most effective means of reducing fatal and nonfatal injuries in motor vehicle crashes (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48). NHTSA estimates that approximately 147,000 lives were saved between 1975 and 2001 because of seat belt use (NHTSA 2002b, 2). However, failure to buckle up continues to result in thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of injuries each year at an estimated societal cost of $26 billion in medical care, lost productivity, and other injury-related costs (Blincoe et al. 2002, 55).

Seat belts protect vehicle occupants during a crash in two ways. They reduce the frequency and severity of occupant contact with the vehicle’s interior, and they prevent ejection from the vehicle (Evans 1991, 232). Specifically, when a crash occurs, occupants are traveling at the vehicle’s original speed at the moment of impact. Seat belts help prevent occupants from rapid and penetrating contact with the steering wheel, windshield, or other parts of the vehicle’s interior immediately after the vehicle comes to a complete stop, reducing the fatalities and injuries caused by this “second collision.” Seat belts also protect occupants from ejection, one of the most severe events that can occur in a

crash. Nearly half of the reduction in fatality risk from using seat belts in cars and light trucks can be traced to the prevention of ejection from vehicles (Evans 1991, 247).

In all types of crashes involving passenger cars, seat belts reduce the risk of fatal injury for drivers and front-seat passengers by about 45 percent; in light trucks, the reduction is about 60 percent (Kahane 2000, 28).2 Moreover, seat belts reduce the risk of moderate-to-critical injury by 50 percent in crashes for passenger vehicle occupants and by 65 percent for light truck occupants (NHTSA 2002b, 1).3 Belt use by rear-seat occupants is also beneficial, not only for the rear-seat passengers but also for the driver and front-seat passengers. A Japanese study of crashes resulting in occupant injury found that unbelted rear-seat occupants increase the risk of death for belted front-seat occupants by nearly fivefold. The increased risk of injury comes from unbelted rear-seat occupants, who are thrown forward into the back of the front seat with immense force in a crash (Ichikawa et al. 2002, 43). An earlier study also found that unbelted rear-seat occupants increase the fatality risk to front-seat occupants by nearly 4 percent in all crashes, and by nearly 30 percent in severe frontal crashes (Park 1987, 13). The adverse effect of unbelted rear-seat occupants is presumably attributable to the increased loading force that they impose on front-seat occupants in a crash (Park 1987, 1).

Even a small increase in belt use should have large benefits. NHTSA estimates that a percentage point increase in belt use results in 250 lives saved per year (Glassbrenner 2002, 1). Research on the characteristics of seat belt nonusers suggests that the benefits could be higher, because many of those who refrain from buckling up tend to exhibit other high-risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol use, speeding) and are more frequently involved in crashes (Haseltine 2001).

STUDY CONTEXT

Introduction of Seat Belts

Seat belts first became standard equipment for the driver and front-seat occupants in 1964 in response to state laws (O’Neill 2001). Then, in 1966, the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act authorized the federal government to establish national safety standards for motor vehicles and created a new agency, subsequently known as NHTSA, to carry out this function.4 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) 208 was one of the original 19 safety regulations. It required that, effective January 1, 1968, all new cars be equipped with both lap belts and shoulder harnesses in the front outboard seating positions and lap belts in other seating positions (Kratzke 1995, 1).5 In 1973 the federal standard was upgraded to require three-point belt systems that connect the shoulder to the lap belt for the front seating positions (O’Neill 2001).

Despite the requirement that vehicles be equipped with seat belts, belt use was low. According to an observational survey of drivers, lap belt use alone ranged from 9 to 16 percent for 1968 to 1971 model-year (MY) vehicles; shoulder and lap belt use ranged from 1 to 6 percent for the same MY (Robertson et al. 1972). Although some efforts were made to educate drivers about the benefits of belt use, studies by NHTSA and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety indicated that educational efforts alone were not effective in increasing belt use (O’Neill 2001; States 1973, 434–435). Thus, NHTSA turned to technological solutions to boost belt use.

Seat Belt Ignition Interlock

The primary focus of the newly created National Highway Traffic Safety Administration was on passive restraint systems—primarily air bags, but also automatic seat belts (Kratzke 1995, 2). These systems would

automatically protect vehicle occupants, hence the term “passive restraints.” Both technical and political factors delayed their introduction. Thus, on January 1, 1972, as an alternative to passive restraints, NHTSA required that all cars manufactured for sale in the United States be equipped with a flashing light and buzzer seat belt reminder system, which activated continuously for at least 1 minute if the vehicle was placed in gear and the driver or front outboard passenger was not belted (Federal Register 1971, 4601). Soon thereafter, NHTSA required that, effective August 15, 1973, all new cars not providing automatic protection be equipped with an ignition interlock that prevented the vehicle from starting if the driver or front-seat passengers were not buckled up (Federal Register 1973). The interlock requirement was intended as an interim measure to increase belt use until acceptable automatic systems became available (Kratzke 1995, 2).

The interlock immediately boosted belt use rates, but some motorists found the system intrusive and learned to disconnect it. In response to numerous complaints, Congress rescinded the interlock requirement 1 year later, in 1974. Legislation was passed6 that prohibited NHTSA from issuing any future safety standard that required either an interlock system or a continuous buzzer warning that sounded for more than 8 seconds after the ignition was turned to the “on” or “start” position. NHTSA revised FMVSS 208 accordingly. The modified standard, which went into effect for cars produced after February 1975 and remains in effect today, requires manufacturers to provide a warning light of no more than 4 to 8 seconds that is activated when the ignition is turned on and a buzzer that sounds for the same duration unless the driver is belted.7

Seat Belt Use Laws

Following the interlock requirement interdiction, NHTSA returned its focus to passive restraints to encourage belt use. The history of this 15-year controversy is too lengthy to record here, but in 1984 a regulation was crafted by then Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole that resulted in the phase-in of automatic protection systems—both passive

seat belts and air bags—but offered the possibility of rescinding the requirement if enough states enacted mandatory seat belt use laws that met NHTSA’s regulatory criteria (Kratzke 1995, 8).8 The regulation resulted in the phase-in of automatic protection systems—both passive belts and air bags. Air bags, in conjunction with manual lap and shoulder belts, proved to be more comfortable, effective, and popular with consumers. Automakers began switching from passive belts to air bags, which Congress ultimately mandated. The regulation also stimulated many states to pass seat belt use laws in what has proved to be one of the most effective approaches for increasing belt use (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48).

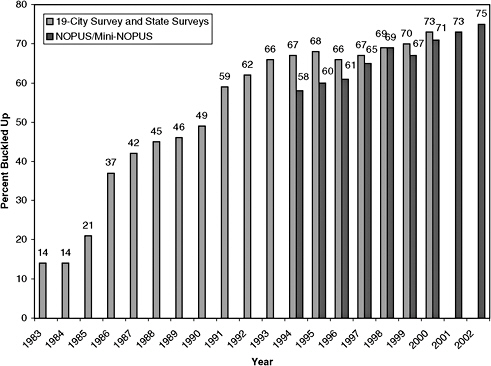

New York, in 1984, was the first state to enact seat belt use legislation. By 1992, largely in response to industry lobbying, 42 states and the District of Columbia had enacted belt use laws (Haseltine 2001). Observed belt use rates rose accordingly, from 14 percent in 1984 to 62 percent in 1992 (Figure 1-1). Today, all states except New Hampshire have belt use laws that apply to adults.9 According to NHTSA’s National Occupant Protection Use Survey (Glassbrenner 2002, 1), observed national belt use rates reached 75 percent in 2002. In the past decade, however, the rate of belt use gains has slowed (Figure 1-1), in part because of the reluctance of many states to promote enforcement through “primary” seat belt use laws (i.e., those that specify failure to buckle up as the sole justification needed to stop and cite a motorist).10 The slower rate of progress also reflects the difficulty of convincing the remaining group of nonusers to buckle up.

TECHNOLOGY REVISITED

Since the interlock requirement interdiction nearly 30 years ago, the protection afforded by seat belts in crashes has become widely recognized, seat belt use laws are nearly universal, belt use rates have increased

Figure 1-1 U.S. observed seat belt use. [Sources: NHTSA, 1983–1990: 19-City Survey; 1991–2000: State Surveys; 1994–2002: National Occupant Protection Use Survey (NOPUS)/Mini-NOPUS.]

sharply, and seat belts are better designed and more comfortable to wear. In addition, technologies that monitor the driver and make driving safer and easier are rapidly appearing on vehicles. They include intelligent cruise control and collision- and road departure–avoidance warning systems. Motorists are becoming accustomed to such technologies, and the cost of their installation is declining as sensors and other facilitating technologies are manufactured in volume.

In 1998, NHTSA was petitioned to mandate effective belt use technologies, such as belt reminder systems that go beyond the existing 8-second reminder.11 However, NHTSA denied the petition, stating that

it did not have the authority to require audible warnings outside the 8-second reminder (Federal Register 1999, 60,625).

Then, Ford Motor Company introduced an enhanced seat belt reminder system—a system that goes beyond the NHTSA-required 4- to 8-second belt reminder—for the U.S. market in selected MY 2000 passenger vehicles. Following the NHTSA-required 8-second reminder, the Ford BeltMinder™, a registered trademark of Ford Motor Company, resumes a warning chime and flashing light at approximately 65 seconds if the driver remains unbuckled while the engine is running and the vehicle is moving at more than 3 mph (4.8 km/h). The system flashes and chimes for 6 seconds; then it pauses for 30 seconds. This cycle repeats for up to 5 minutes. By MY 2002, all Ford vehicles were equipped with the enhanced belt reminder for the driver, with a phase-in for the right front-seat passenger starting with MY 2003 vehicles.

In February 2002, Dr. Jeffrey Runge, NHTSA Administrator, urged the automobile industry to follow Ford’s lead and voluntarily introduce enhanced belt reminder systems and other appropriate technologies as an added incentive for motorists to buckle up.12

Belt reminder systems are also being developed for the European and Australian markets to convince remaining groups of belt nonusers in those markets to buckle up. The European New Car Assessment Program (EuroNCAP), which is modeled on a similar U.S. consumer safety rating program,13 offers bonus points for vehicles equipped with belt reminder systems that meet certain performance criteria, thus providing a strong incentive for manufacturers to introduce effective technologies.

KEY STUDY ISSUES, DEFINITION OF TERMS, AND APPROACH

In light of the history of the 1970s interlock experience, a major goal of manufacturers is to introduce technologies that encourage seat belt use but that are acceptable to customers and will not be overly intrusive. Thus, the manufacturers are developing belt reminder systems for the new car market rather than more aggressive interlock technologies that

interfere with vehicle operations. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this study, the full range of seat belt use technologies, from belt reminder systems to interlocks, is being considered.

The first two tasks of the committee are to consider what is known about the potential effectiveness and acceptability of the technologies. “Effectiveness” is typically measured as the increase in belt use attributable to a technology. Because seat belt use is clearly correlated with fatality and injury reduction, it serves as a reasonable proxy for these consequences (i.e., lives saved and injuries avoided), which are not currently available in sufficient numbers to provide statistically reliable estimates.

“Acceptability” is closely related to effectiveness, and they can be inversely related. For example, initially the 1973 ignition interlock was very effective in increasing belt use. However, consumers quickly learned to defeat the system, and Congress ultimately prohibited its installation in passenger vehicles. Thus, if a technology is so intrusive that a consumer is motivated to defeat it by disabling, selective purchasing, or political action (as in the 1970s), a technology’s actual effectiveness may reduce to zero no matter what its potential safety impact might be. Although consumer acceptability is a concern, the vast majority of motorists today buckle up, in contrast to the 1970s, and should not even be aware of the new systems, particularly if they are engineered properly to reflect typical belt-buckling habits.14

The committee approached the first task of its charge—to determine the potential effectiveness of the technology—by reviewing the literature for studies of early experience (1970s) with belt reminder and interlock systems. It then examined more recent but limited field data on the effectiveness of current enhanced belt reminder systems. It also sought proprietary information directly from the major automobile manufacturers and suppliers by meeting with them about new belt system characteristics, plans for deployment, and industry assessments of system effectiveness.

|

14 |

For example, research on buckling habits, which is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4, suggests that the vast majority of drivers buckle up after starting the vehicle, even when it is first moving. Belt technologies should be designed to reflect these habits. |

Data on likely consumer acceptance of new seat belt use technologies—the second task—were limited and dated. Thus, NHTSA conducted in-depth interviews of belt nonusers (i.e., those who reported not using seat belts all the time) especially tailored for this study to ascertain consumer views on the acceptability and potential effectiveness of technologies ranging from belt reminder to interlock systems. Focus groups of full-time belt users were also conducted to ensure that proposed technologies would not have unintended negative effects on those who consistently buckle up. NHTSA developed its approach after discussing various options for soliciting consumer response with the committee. Individual committee members commented directly on the study design, screening criteria, and interview and focus group guides. Finally, the committee requested market research data directly from the automobile manufacturers with regard to consumer acceptance of new seat belt use technologies.

To address the third task—to determine whether changes in regulation or legislation are necessary to facilitate introduction of effective technologies—the committee requested that NHTSA’s Chief Legal Counsel provide the agency’s current interpretation of the statutory and regulatory restrictions affecting both belt reminder and interlock systems.

ORGANIZATION OF REPORT

The remainder of this report elaborates the committee’s findings from its investigation of each task of its charge. In Chapter 2, an overview is provided of what is known about the target group for seat belt technologies—belt nonusers—including key factors that affect belt use, and implications for current technology introduction are described. In Chapter 3, the history of the 1970s experience with belt reminder and interlock systems, as well as other key approaches for increasing belt use, are reviewed with an eye to what lessons can be brought forward to today. Chapter 4 is focused on current information concerning the potential effectiveness and acceptability of recently introduced seat belt use technologies. The results of the literature review, manufacturer briefings, and NHTSA interviews and focus groups conducted for this

study are summarized, and the implications for the introduction of belt use technologies are discussed. In Chapter 5, NHTSA’s interpretation of the current statutory and regulatory prohibitions concerning the introduction of new seat belt use technologies is reviewed, and manufacturers’ concerns are explored. The committee then provides its findings and recommendations concerning the role of technology in increasing belt use.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

NHTSA National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

TRB Transportation Research Board

Blincoe, L., A. Seay, E. Zaloshnja, T. Miller, E. Romano, S. Luchter, and R. Spicer. 2002. The Economic Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2000. DOT-HS-809-446. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, May.

Dinh-Zarr, T. B., D. A. Sleet, R. A. Shults, S. Zaza, R. W. Elder, J. L. Nichols, R. S. Thompson, and D. M. Sosin. 2001. Reviews of Evidence Regarding Interventions to Increase the Use of Safety Belts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 21, No. 4S, Nov., pp. 48–65.

Evans, L. 1991. Traffic Safety and the Driver. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

Federal Register. 1971. Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. Occupant Crash Protection in Passenger Cars, Multipurpose Passenger Vehicles, Trucks, and Buses. Vol. 36, No. 47, pp. 4600–4606.

Federal Register. 1973. Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208. Occupant Crash Protection. Vol. 38, pp. 16,072–16,074.

Federal Register. 1999. Response to Petition. Vol. 64, Nov. 5.

Glassbrenner, D. 2002. Safety Belt and Helmet Use in 2002—Overall Results. DOT-HS-809-500. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Sept.

Haseltine, P. W. 2001. Seat Belt Use in Motor Vehicles: The U.S. Experience. In 2001 Seat Belt Summit, Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety, Inc., Jan. 11–13. www.actsinc.org/Acrobat/SeatbeltSummit2000.pdf.

Ichikawa, M., S. Nakahara, and S. Wakai. 2002. Mortality of Front-Seat Occupants Attributable to Unbelted Rear-Seat Passengers in Car Crashes. The Lancet, Vol. 359, Jan. 5, pp. 43–44.

Kahane, C. J. 2000. Fatality Reduction by Safety Belts for Front-Seat Occupants of Cars and Light Trucks. DOT-HS-809-199. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Dec.

Kratzke, S. R. 1995. Regulatory History of Automatic Crash Protection in FMVSS 208. SAE Technical Paper 950865. International Congress and Exposition, Society of Automotive Engineers, Detroit, Mich., Feb. 27–March 2.

NHTSA. 1999. Fourth Report to Congress: Effectiveness of Occupant Protection Systems and Their Use. DOT-HS-808-919. U.S. Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 2002a. Traffic Safety Facts 2001: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System. DOT-HS-809-484. U.S. Department of Transportation, Dec.

NHTSA. 2002b. Traffic Safety Facts 2001: Occupant Protection. DOT-HS-809-474. U.S. Department of Transportation.

O’Neill, B. 2001. Seat Belt Use: Where We’ve Been, Where We Are, and What’s Next. In 2001 Seat Belt Summit, Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety, Inc., Jan. 11–13. www.actsinc.org/Acrobat/SeatbeltSummit2000.pdf.

Park, S. 1987. The Influence of Rear-Seat Occupants on Front-Seat Occupant Fatalities: The Unbelted Case. GMR-5664. General Motors Research Laboratories, Warren, Mich., Jan. 8.

Robertson, L. S., B. O’Neill, and C. Wixom. 1972. Factors Associated with Observed Safety Belt Use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 13, pp. 18–24.

States, J. D. 1973. Restraint System Usage—Education, Electronic Inducement Systems, or Mandatory Usage Legislation? SAE Paper 1973-12-0027, pp. 432–442.

TRB. 1990. Special Report 229: Safety Research for a Changing Highway Environment. National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Williams, A. F., J. K. Wells, and C. M. Farmer. 2002. Effectiveness of Ford’s Belt Reminder System in Increasing Seat Belt Use. Injury Prevention, Vol. 8, pp. 293–296.