EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Using seat belts is one of the most effective strategies available to the driving public for avoiding death and injury in a crash (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48). Today, however, nearly 35 years after the federal government required that all passenger cars be equipped with seat belts, approximately one-quarter of U.S. drivers and front-seat passengers are still observed not to be buckled up (Glassbrenner 2002, 1). Nonusers tend to be involved in more crashes than belt users (Reinfurt et al. 1996, 215), and belt use is lower—about 40 percent for drivers—in severe crashes (O’Neill 2001). Moreover, at observed national belt use rates of 75 percent, the United States continues to lag far behind the 90 to 95 percent belt use rates achieved in Canada, Australia, and several northern European countries.

Convincing motorists to buckle up is a top priority of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) as it looks for ways to reduce the 42,000 deaths and more than 3 million injuries that occur each year on U.S. highways (NHTSA 2002a). NHTSA is urging industry to deploy vehicle-based technologies, such as seat belt reminder systems, to encourage further gains in belt use, but the agency is prohibited from requiring such technologies by federal legislation dating back to 1974. A brief history of the events leading up to this action and its impact on technology introduction today are provided in a subsequent section.

Congress requested the present study1 to

-

Examine the potential benefits of technologies designed to increase belt use,

-

Determine how drivers view the acceptability of the technologies, and

-

Consider whether legislative or regulatory actions are necessary to enable their installation on passenger vehicles.2

|

1 |

The request was contained in Conference Report 107-308 to accompany Appropriations for the Department of Transportation and Related Agencies for fiscal year 2002, June 22, 2001 (see Appendix A). Given the nature of the charge, the committee did not analyze other strategies for increasing seat belt use, such as seat belt use laws, enforcement, and fines. |

|

2 |

Passenger vehicles include cars and light-duty trucks driven for personal use (i.e., sport utility vehicles, vans, and pickup trucks). |

In short, congressional interest in this study is focused on an assessment of the potential for technology to increase seat belt use and the extent to which federal laws and regulations pertaining to these technologies may inhibit their introduction.

BENEFITS OF SEAT BELT USE

Properly used seat belts are one of the most effective measures for reducing death and injury on the highway (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48). Buckling up can reduce the risk of fatal injury for drivers and front-seat occupants of passenger cars involved in crashes by about 45 percent. The fatality reduction for front-seat belt wearers in light trucks is 60 percent (Kahane 2000, 28–29). Moreover, seat belts reduce the risk of moderate-to-critical injury in crashes by 50 percent for passenger vehicle occupants and by 65 percent for light truck occupants (NHTSA 2002b).3

NHTSA estimates that approximately 147,000 lives were saved between 1975 and 2001 because of seat belt use (NHTSA 2002b). If current belt nonusers in passenger vehicles buckled up, thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of injuries could be prevented each year at an estimated societal savings of $26 billion in medical care, lost productivity, and other injury-related costs (Blincoe et al. 2002, 55). Because of the proven effectiveness of seat belts, measures to encourage further belt use would have big payoffs. NHTSA estimates that a percentage point increase in belt use would result in 250 lives saved per year (Glassbrenner 2002, 1). As the pool of nonusers shrinks, more lives are saved for each incremental point increase in belt use. The reason is that those most resistant to buckling up tend to exhibit other high-risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol use, speeding) and are more frequently involved in crashes (Blincoe et al. 2002, 53).

Seat belt use is also cost-effective. The marginal monetary cost of seat belt use is zero because all U.S. passenger vehicles are required to be equipped with seat belts. The marginal nonmonetary costs are modest. They include the time and effort required to buckle up and, for some, the discomfort of wearing the belt.

REASONS FOR BELT NONUSE

If seat belts are so effective, why don’t more motorists buckle up? Unlike air bags or automatic restraint systems, manual belts require action on the part of drivers and passengers. Reasons for not using belts stem from a complex mix of situational, habitual, and attitudinal factors.

Many drivers and vehicle occupants report that they would like to be wearing a seat belt in a crash but have not acquired the habit of buckling up on all trips. For this group (referred to hereafter as “part-time users”), belt use is situational; they tend to buckle up when the weather is poor or when they are taking longer trips on high-speed roads where they perceive driving as riskier. In surveys, these users report that the primary reasons for their not buckling up are driving short distances, forgetting, being in a hurry, or discomfort from the belt (Block 2001, v).

In contrast, the much smaller group of motorists who never or rarely use their belts—the so-called “hard-core nonusers”—report negative attitudes toward seat belts as the primary reason for nonuse. These include discomfort, unfounded claims that belts are dangerous in a crash (e.g., could trap the driver in the vehicle), infringement of personal freedom and resentment of authority, and the attitude that they “just don’t feel like wearing them” (Block 2001, v).

According to NHTSA’s most recent telephone survey on occupant restraint issues (Block 2001, 12), one-fifth of drivers can be characterized as part-time users, that is, they report using their belts most or some of the time, and about 4 percent as hard-core nonusers, those who report never or rarely using their belts.4 The latter group is small but has a high crash risk. Unbelted drivers have significantly more traffic violations, higher crash involvement rates, higher arrest rates, and higher alcohol consumption than those who buckle up all or part of the time (Reinfurt et al. 1996).

The distinction between these two groups is important from the perspective of technology effectiveness and acceptability. If, in fact, the majority of belt nonusers are aware of the benefits of seat belts but have not

|

4 |

As discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, these categorizations are approximate. For example, 83 percent of drivers reported wearing their seat belts “all the time.” However, 8 percent of these full-time users reported in a follow-up question that they had not worn their seat belts while driving at some time during the past week (Block 2001, 24). |

developed the habit of belt use in all situations, their behavior may be amenable to a belt reminder system. However, more aggressive systems may be needed to reach the small group of hard-core nonusers.

OVERVIEW OF STRATEGIES FOR INCREASING BELT USE

The history of NHTSA’s approach to occupant protection is instructive in understanding the agency’s current policies and regulatory constraints, particularly as they apply to the use of technology to increase seat belt use.

Comprehensive automobile safety legislation in 1966 established the federal role in highway safety regulation. Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) 208, which required the installation of lap and shoulder belts in all new passenger vehicles,5 was one of the 19 original safety standards put in place by the newly created National Highway Safety Bureau (Kratzke 1995, 1).6 It soon became apparent, however, that motorists would not use the belts voluntarily with much regularity. Thus, the renamed National Highway Traffic Safety Administration began promoting so-called “passive restraint systems,” primarily air bags but also automatic belt systems (Kratzke 1995, 1).

Negative public and political reaction to such systems, stemming in part from their early stage of development, led NHTSA in 1972 to provide manufacturers with an alternative—a required 60-second flashing light and buzzer system to remind motorists to buckle up (Robertson 1975, 1320). Soon thereafter, the agency required that, effective August 15, 1973, all passenger vehicles not providing automatic protection be equipped with an interlock system, which prevented the engine from starting if any front-seat occupant was not buckled up. The interlock requirement was intended as an interim measure to increase belt use until acceptable automatic systems became available (Kratzke 1995, 2).

With seat belt use rates of only 12 to 15 percent (Haseltine 2001), no laws requiring belt use, lap and shoulder belt systems that many mo-

torists found clumsy and uncomfortable to wear, and unreliable occupant sensing systems, it is hardly surprising that the ignition interlock requirement met almost immediately with strong public and political opposition. Although by some reports belt use rates soared to about 60 percent immediately following the installation of interlock systems, some motorists learned to disable the system, and others began to complain to their elected representatives (Kratzke 1995, 3). One year after the interlock requirement took effect, Congress enacted legislation prohibiting NHTSA from requiring either ignition interlocks or continuous buzzer warnings of more than 8 seconds.7 The agency revised FMVSS 208 accordingly, retaining a requirement for only a 4- to 8-second warning light and buzzer8 of similar duration that is activated when front seat belts are not fastened at the time of ignition. This standard still applies today (Federal Register 1974, 42,692–42,693).

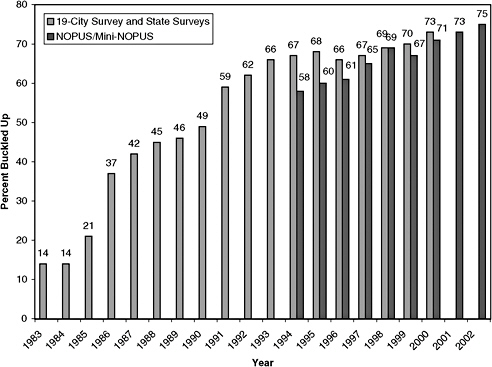

Following the interlock requirement interdiction, NHTSA’s focus returned to passive restraint systems. In 1984, then Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole crafted a final rule providing for a phase-in of air bags and automated belts, but with the possibility of rescinding this requirement if, by 1989, two-thirds of the nation’s population was covered by state-mandated seat belt use laws meeting NHTSA’s requirements (Kratzke 1995, 8). The deadline was not met, but seat belt use laws were rapidly introduced and have proved to be one of the most effective approaches for increasing belt use (Dinh-Zarr et al. 2001, 48). Today, all states except New Hampshire have belt use laws that apply to adults, and observed use rates have grown from about 14 percent in 1984 to about 75 percent today (Figure ES-1), largely the result of laws coupled with well-publicized enforcement (O’Neill 2001).9 Over the past decade, however, the rate of belt use gains has slowed, in part because of the reluctance of many states to promote enforcement through

Figure ES-1 U.S. observed seat belt use. [Sources: NHTSA, 1983–1990: 19-City Survey; 1991–2000: State Surveys; 1994–2002: National Occupant Protection Use Survey (NOPUS)/Mini-NOPUS.]

“primary” seat belt use laws (i.e., those that specify failure to buckle up as the sole justification needed to stop and ticket a motorist).10 The slower rate of progress also reflects the difficulty of convincing the remaining group of nonusers to buckle up.

TECHNOLOGY REVISITED

Congress and NHTSA have expressed interest in the potential of technology to increase seat belt use. While current federal law prohibits NHTSA from mandating in-vehicle seat belt use technologies other than

the limited 4- to 8-second reminder system, manufacturers are not prevented from voluntarily adopting such technologies, including interlocks. However, the U.S. automobile industry has been wary of pursuing aggressive approaches, such as those specified in the NHTSA prohibition, for both perceived legal and marketing reasons. Nevertheless, Ford Motor Company has initiated a technology enhancement with the introduction of its BeltMinder™ (a registered company trademark) now on all Ford vehicles—a system of warning chimes and flashing lights that operates intermittently for up to 5 minutes to alert and remind the unbelted driver to buckle up. NHTSA Administrator Dr. Jeffrey Runge urged other manufacturers to follow Ford’s lead.11 Many have responded with plans to deploy enhanced belt reminder systems—technologies that go beyond the NHTSA-required 4- to 8-second reminder—in the United States, with introductions to be phased in during the 2004–2005 model years. All the planned systems include light and chime components but vary in their loudness, urgency, and duration.

In Sweden, Australia, and Japan, where belt use rates are substantially higher than in the United States, enhanced belt reminder systems are being tested and put in vehicles to help persuade the small remaining group of belt nonusers, who are overrepresented in severe crashes, to buckle up. Technological solutions were thought to hold more promise than additional public information campaigns and enfocement efforts (Larsson 2000, 1–2). The European consumer information New Car Assessment Program—EuroNCAP—has established protocols for such systems and rewards manufacturers who meet them with higher safety ratings.12 No manufacturers are currently developing interlock systems, although General Motors is working with a small business, D&D Innovations, Inc., to make available a seat belt shifter lock as an aftermarket option in the United States.

Clearly, today’s environment is far more conducive to the successful introduction of technologies for increasing seat belt use than was that of the early 1970s with respect to both technological advances and driver behavior. Belt use is compulsory in all but one state, belt use rates are

significantly higher, belts are better designed, and sensing technologies are more sophisticated and reliable. Nevertheless, the pace and type of technology introduction continue to be affected by the interlock experience. While sympathetic to NHTSA’s appeal for enhanced belt use technologies, the industry is understandably sensitive to the implications of overly aggressive and costly systems that are poorly accepted by potential customers. And for its part, NHTSA is still prohibited by Congress from mandating more aggressive technologies.

STUDY APPROACH

In view of the history of seat belt use technology development in the United States, the successful introduction of new technologies is likely to depend on a careful balancing of system effectiveness and acceptability. “Effectiveness” is typically measured as the increase in belt use attributable to a technology. Since belt use is clearly correlated with fatality and injury reduction, it serves as a reasonable proxy for these consequences (which are not currently available in sufficient numbers to provide statistically reliable measures). “Acceptability” is closely related to effectiveness in that motorists are inclined to resist, by one means or another, any technology that they find excessively intrusive. And if they defeat it by disabling, selective purchasing, or political action (as they did in the early 1970s), a technology’s actual effectiveness may reduce to zero no matter what its potential safety impact might be. Hence to be effective, a seat belt use technology must be sufficiently intrusive to prompt motorists to act, but not so intrusive that it exceeds their threshold for tolerance.

The available technologies can be ordered logically according to degree of intrusiveness. They range from belt reminder systems that provide a minimal visual and auditory prompt to buckle up, to demanding ones that are more insistent and persistent, to interlock systems that simply prohibit the unwanted behavior (e.g., the unbelted driver is unable to shift the car into gear). As a general principle, which is corroborated by the evidence in Chapter 4, the more intrusive the system, the less acceptable it is likely to be to motorists. That said, it is important to note that acceptability is not an issue for the majority of drivers who are

habitual seat belt users and thus will never or rarely experience the intervention, no matter how intrusive it is.

The study committee investigated what is known about both the effectiveness and the acceptability of seat belt use technologies. It reviewed the available literature, held closed-session briefings with key automobile manufacturers and suppliers, and reviewed the results of indepth interviews and focus groups conducted by NHTSA for this study.13 Interviews were thought to be more useful than a large population survey because demonstration of the technologies with follow-up questions would provide more valid data than asking hypothetical questions to respondents unfamiliar with the devices. The objective of the in-depth interviews and focus groups was to obtain a greater understanding of the perceived effectiveness and acceptability of four technologies that were judged to span a wide range of intrusiveness—from the Ford BeltMinder, to a more aggressive Saab prototype belt reminder system (where the chime increases in intensity with vehicle speed), to an entertainment interlock (which prevents playing the radio or stereo unless belts are buckled), to a transmission interlock (which prevents putting the vehicle in gear unless belts are buckled). The results show a convergence of responses that are indicative of the likely consumer reaction to new seat belt use technologies. Finally, the committee was briefed by the NHTSA Chief Counsel in an effort to learn to what extent the agency views the current statutory and regulatory restrictions on seat belt use technologies as impediments to their introduction in the marketplace.

FINDINGS

New seat belt use technologies exist that present opportunities for increasing belt use without being overly intrusive. The current NHTSA-required belt reminder has proved ineffective in further increasing belt use (Westefeld and Phillips 1976, 2). There is no scientific basis for the 8-second maximum duration of the system. Many motorists—the

majority of whom do not buckle up until some time after starting their vehicles (70 percent according to General Motors’ survey data)—report that they ignore the chime, simply do not hear it over the radio, or have forgotten it by the time they are backing down the driveway, and that they could use a stronger reminder to buckle up. In contrast, the results from the NHTSA interviews conducted for this study and the manufacturer briefings suggest that motorists would be aware of and heed the characteristics of enhanced belt reminder systems now being introduced by industry. More important, although the results are based on a limited sample, many part-time users interviewed by NHTSA—the primary target group for the technology—were receptive to the new systems. Nearly two-thirds rated the reminders “acceptable,” and approximately 80 percent thought that they would be “effective.”

Preliminary research on the only system currently deployed in the United States—the Ford BeltMinder—found a statistically significant 7 percent increase in seat belt use for drivers of vehicles equipped with the Ford system compared with drivers of unequipped late-model Fords (Williams et al. 2002, 295).14 The results were gathered in two Oklahoma locations and provide a snapshot of belt use behavior, but they are suggestive of the potential benefits of enhanced belt reminder systems. A subsequent study in Boston of drivers with BeltMinder-equipped Ford vehicles found that, of the two-thirds who activated the system, three-quarters reported buckling up and nearly half of all respondents said their belt use had increased (Williams and Wells 2003, 6, 10).

According to the automobile manufacturers and suppliers, enhanced belt reminder systems can be provided at minimal cost for front-seat occupants because of the availability of sensors that can detect the presence of front-seat occupants for advanced air bag systems.15 Rear-seat systems appear costly compared with front-seat systems because of the absence of rear-seat sensors on many vehicles, installation complexities (e.g., removable seats, child seats), and low rear-seat occupancy rates. However, lower-cost systems that alert the driver when rear-seat occu-

pants have not buckled up or have unbuckled their belts during a trip are currently available on some vehicles in Europe. The risks posed to all vehicle occupants by unbelted rear-seat occupants, particularly in more severe crashes, suggest that the benefits of full-scale rear-seat reminder systems could be significant (Ichikawa et al. 2002). Furthermore, recent efforts by NHTSA and industry to encourage parents to place their children in rear seats away from front-seat air bags has increased parental interest in systems that monitor belt use in rear seats.

Transmission interlock systems are perceived to be highly effective—more than 85 percent of all respondents to the NHTSA interviews and focus groups rated them effective. However, fewer than half rated them acceptable. The highest percentage of respondents who rated the transmission interlock not acceptable—71 percent—came from the small group of hard-core nonusers. Objections to the entertainment interlock, which was thought to be most effective for younger drivers, were weaker among full-time users and even among the hard-core nonusers. This result can be attributed in part to the fact that the system would not be experienced by some people (e.g., older people who do not use the radio, drivers on short trips) or could be circumvented (e.g., by installing an aftermarket stereo). Part-time users, who found the entertainment interlock slightly more objectionable than the transmission interlock, were the exception.

Interlock systems could be engineered to avoid many motorists’ objections. For example, they could be designed to enable drivers to start their cars without buckling up and to drive in reverse and perhaps at low speeds to accommodate the majority of drivers who do not buckle up before starting their vehicles. However, the negative reaction indicated by the NHTSA interviews and focus groups and the hesitancy of industry to reintroduce interlock systems for the general driving public suggest that, for the moment, their use be considered only for certain high-risk groups (e.g., drivers impaired by alcohol, teenage drivers) who are overrepresented in crashes.

The current legislation prohibiting NHTSA from requiring new seat belt use technologies other than the ineffective 4- to 8-second belt reminder is outdated and unnecessarily prevents the agency from requiring effective technologies to increase belt use. Seat belt use has grown fivefold since 1974. Many more motorists now recognize the benefits of

seat belts and appear to be receptive to their use. However, NHTSA does not currently have the legislative authority to establish performance standards to encourage development of minimum performance criteria for the most effective systems or to require them to be sold in the U.S. market.

RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of its findings, the committee reached consensus on the following recommendations:

-

Congress should amend the statute regarding belt reminder systems by lifting the restrictions on systems with lights and chimes longer than 8 seconds, which would provide NHTSA more flexibility and the authority to require effective belt reminder technologies. At this time, the committee does not see any compelling need to delete the prohibition on requiring interlock systems. However, this subject should be revisited in 5 years (see Recommendation 8).

-

Every new light-duty vehicle should have as standard equipment an enhanced belt reminder system for front-seat occupants with an audible warning and visual indicator that are not easily disconnected. Any auditory signal should be audible above other sounds in the vehicle. For the short term, manufacturers should be encouraged to provide these systems voluntarily so that field experience can be gained concerning the absolute and differential effectiveness and acceptability of a range of systems. Those who rate vehicles—NHTSA, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Consumers Union—should be urged to note those vehicles that have belt reminder systems in their consumer safety rating publications.

-

NHTSA should encourage industry to develop and deploy enhanced belt reminder systems in an expeditious time frame, and NHTSA should monitor the deployment. As differences in effectiveness and acceptability of belt reminder systems are identified, manufacturers should install systems that are determined by empirical evidence to result in the greatest degree of effectiveness while remaining acceptable to the general public. Should voluntary efforts not produce sufficient results, NHTSA should mandate the most effective acceptable

-

systems as determined by the current data. The agency should also conduct studies to identify factors that will increase the effectiveness and acceptability of the systems.

-

Rear-seat reminder systems should be developed at the earliest possible time as rear-seat sensors become available, to take advantage of the benefits of restrained rear occupants to the safety of both front-and rear-seat occupants. Until that time, manufacturers should provide systems that notify the driver if rear-seat occupants either have not buckled up or have unbuckled their belts during a trip.

-

NHTSA and the private sector should strongly encourage research and development of seat belt interlock systems for specific applications. For example, the courts should consider requiring the use of interlocks for motorists with driving-under-the-influence-of-alcohol convictions or with high numbers of points on their driver’s licenses. Interlocks could also be made available for other high-risk groups, such as teenage drivers. Insurance companies could lower premium rates for young drivers who install interlock systems. Finally, interlocks could be installed on company fleets.

-

Seat belt use technologies should be viewed as complementary to other proven strategies for increasing belt use, most particularly enactment of primary seat belt use laws that enable police to pull over and cite drivers who are not buckled up and well-publicized enforcement programs. Seat belt use technologies have the potential to increase belt use, but their effect is largely confined to new vehicle purchasers, whereas seat belt use legislation affects all drivers.

-

Congress should provide NHTSA with funding of about $5 million annually16 to support a multiyear program of research on the effectiveness of different enhanced seat belt reminder systems. NHTSA should coordinate its efforts with other federal agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that are conducting related research. The research could involve undertaking more

-

comprehensive studies of the effects of belt reminder systems on belt use; conducting controlled fleet studies of aggressive reminder systems; gathering more survey data on the effectiveness and acceptability of belt reminder systems from existing NHTSA and public health sources; and examining design issues, such as loudness of the chime, desirability of muting the radio when the chime is sounding, duration and cycling of the systems, and the presence and design of any cutoff capability. This research should help establish the scientific basis for regulation of belt reminder systems should regulation be needed.

-

In 2008 another independent review of seat belt use technologies should be conducted to evaluate progress and to consider possible revisions in strategies for achieving further gains in belt use, including elimination of the statutory restriction against NHTSA’s requiring vehicle interlock systems.

The benefits of enhanced seat belt use technologies could be significant. If increases in belt use rates on the order of 7 percent (or 5 percentage points) found in the initial evaluation of the Ford BeltMinder could be achieved nationally, a minimum of 1,250 additional lives could be saved annually, according to NHTSA estimates (Glassbrenner 2002, 1), once all passenger vehicles have been equipped with enhanced belt reminder systems. These figures do not include the potential lives saved from the installation of reminder systems for rear seat belts or the hundreds of thousands of injuries that could also be prevented each year. The modest additional costs of installing the systems, particularly once sensor systems are available for all seating positions, and the annual $5 million cost of conducting the recommended multiyear research program, constitute a small price to pay for the lives saved and the hundreds of thousands of costly injuries prevented.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

NHTSA National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

AASHTO Journal. 2003. U.S., DOT, NHTSA Launch “Click It or Ticket” Seat-Belt Campaign. Vol. 103, No. 20, May 16, p. 16.

Blincoe, L., A. Seay, E. Zaloshnja, T. Miller, E. Romano, S. Luchter, and R. Spicer. 2002. The Economic Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2000. DOT-HS-809-446. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, May.

Block, A. W. 2001. The 2000 Motor Vehicle Occupant Safety Survey. Vol. 2, Seat Belt Report. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Nov.

Dinh-Zarr, T. B., D. A. Sleet, R. A. Shults, S. Zaza, R. W. Elder, J. L. Nichols, R. S. Thompson, and D. M. Sosin. 2001. Reviews of Evidence Regarding Interventions to Increase the Use of Safety Belts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 21, No. 4S, Nov., pp. 48–65.

Federal Register. 1974. Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards: Seat Belt Warning System. Vol. 39, No. 236, Dec. 6, pp. 42,692–42,693.

Glassbrenner, D. 2002. Safety Belt and Helmet Use in 2002—Overall Results. DOT-HS-809-500. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Sept.

Haseltine, P. W. 2001. Seat Belt Use in Motor Vehicles: The U.S. Experience. In 2001 Seat Belt Summit, Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety, Inc., Jan. 11–13. www.actsinc.org/Acrobat/SeatbeltSummit2000.pdf.

Ichikawa, M., S. Nakahara, and S. Wakai. 2002. Mortality of Front-Seat Occupants Attributable to Unbelted Rear-Seat Passengers in Car Crashes. The Lancet, Vol. 359, Jan. 5, pp. 43–44.

Kahane, C. J. 2000. Fatality Reduction by Safety Belts for Front-Seat Occupants of Cars and Light Trucks. DOT-HS-809-199. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Dec.

Kratzke, S. R. 1995. Regulatory History of Automatic Crash Protection in FMVSS 208. SAE Technical Paper 950865. International Congress and Exposition, Society of Automotive Engineers, Detroit, Mich., Feb. 27–March 2.

Larsson, P. 2000. Seat Belt Reminder Systems. Vägverket, Swedish National Road Administration, Jan. 21.

NHTSA. 1999. Fourth Report to Congress: Effectiveness of Occupant Protection Systems and Their Use. DOT-HS-808-919. U.S. Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 2002a. Traffic Safety Facts 2001: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System. DOT-HS-809-484. U.S. Department of Transportation, Dec.

NHTSA. 2002b. Traffic Safety Facts 2001: Occupant Protection. DOT-HS-809-474. U.S. Department of Transportation.

O’Neill, B. 2001. Seat Belt Use: Where We’ve Been, Where We Are, and What’s Next. In 2001 Seat Belt Summit, Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety, Inc., Jan. 11–13. www.actsinc.org/Acrobat/SeatbeltSummit2000.pdf.

Reinfurt, D., A. Williams, J. Wells, and E. Rogman. 1996. Characteristics of Drivers Not Using Seat Belts in a High Belt Use State. Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 209–215.

Robertson, L. S. 1975. Safety Belt Use in Automobiles with Starter-Interlock and Buzzer-Light Reminder Systems. American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 65, No. 12, pp. 1319–1325.

Westefeld, A., and B. M. Phillips. 1976. Effectiveness of Various Safety Belt Warning Systems. DOT-HS-801-953. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, July.

Williams, A. F., J. K. Wells, and C. M. Farmer. 2002. Effectiveness of Ford’s Belt Reminder System in Increasing Seat Belt Use. Injury Prevention, Vol. 8, pp. 293–296.

Williams, A. F., and J. K. Wells. 2003. Drivers’ Assessment of Ford’s Belt Reminder System. Traffic Injury Prevention (in press).