3

Public Health and HIV/AIDS Surveillance

This chapter reviews public health surveillance, and HIV and AIDS case reporting, to provide context for the use of such information in Ryan White CARE Act (RWCA) funding formulas. In this report, the Committee distinguishes between the terms “surveillance” and “case reporting.” Surveillance is a more comprehensive term for data collection that can include case reporting, as well as other methods, such as population-based surveys, seroprevalence surveys, and behavioral risk factor surveillance. Case reporting is a subset of surveillance activities in which individuals who are diagnosed with specific diseases or conditions are reported to public health authorities (state or local health departments), typically by medical practitioners and laboratories and pursuant to requirements imposed by state statutes or regulations. This chapter focuses its discussion of HIV/AIDS surveillance on HIV/AIDS case reporting, because it is the predominant method of surveillance used by states to collect information about HIV infection and because it is the most relevant to the RWCA formulas.

PUBLIC HEALTH SURVEILLANCE

Public health surveillance has been defined as the ongoing, systematic collection of public health data, with analysis and dissemination of results and interpretation of these data to those who contributed to them and “all who need to know” (Langmuir, 1963). Public health surveillance was historically used to discover or identify and observe patients with

contagious, infectious diseases and the people with whom they came in contact, to isolate and quarantine them, or take other measures to control the spread of disease (Birkhead and Maylahn, 2000). Since the 1950s, surveillance has gradually expanded to include monitoring disease trends in populations for the purpose of initiating population-based disease-control programs. More recently, traditional models for controlling communicable diseases have also been extended to noninfectious diseases, as well as occupational, environmental, behavioral, biological, and social factors that are believed to contribute to the onset and spread of disease (Thacker, 2000). Surveillance is a process that relies on increasingly sophisticated epidemiological and statistical techniques and requires a large and complex system that stretches from the individual practitioner to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, legal authority to require reporting of diseases resides primarily at the state level. In some states, legislation specifies reporting requirements for particular diseases; in others, legislation delegates authority to the state health department or local boards of health to designate reportable disease by regulation; and some states use both (Thacker, 2000).1 Legislative authorization is necessary because health providers cannot lawfully release or disclose personal medical information about a patient without the patient’s consent.2 Health care facilities

and providers are restricted in their disclosure of medical information by state laws, federal laws, and by Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.3 However, all states have statutes or regulations authorizing and requiring providers and laboratories to report notifiable diseases to the state or local health department (Roush et al., 1999). HIPAA allows covered entities to release this health information to state health departments in compliance with state disease reporting laws (45 C.F.R. § 164.512 [2003]; CDC, 2003c).

States vary in the diseases they obligate physicians, other practitioners, and entities such as laboratories to report, and in the type and amount of information they require. Most systems for reporting infectious diseases require names because public health authorities often need to contact individuals to identify the source of infection, to identify others who may need treatment, and to possibly isolate individuals who pose a danger of infecting others. Name-based reporting has also been advocated as a way to facilitate the elimination of duplicate reports (CDC, 1999). States often require practitioners to report the source of exposure to infection, risk factors, and symptoms. Laboratories must often report a subset of diseases that can be diagnosed by laboratory tests, such as positive tests for measles antibody.

Although states and localities are responsible for collecting surveillance data, they broadly and voluntarily share such information with the federal government. In 1951, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) organized the Conference (now Council) of State and Territorial Epidemiologists to recommend diseases that states should voluntarily report to CDC, and to develop reporting procedures (Koo and

|

|

and some disclosures may be authorized by legislation designed to achieve a justifiable public health purpose. Laws requiring the disclosure of personally identifiable information, such as names and addresses, have been upheld where the law also required that the information be kept secure and confidential and not be disclosed to third parties and prescribed penalties for any violation of confidentiality (Whalen v Roe, 429 U.S. 5890 [1977]), but have been struck down when such protections were not part of the law. Reporting laws that do not include the collection of names or other personally identifiable information rarely raise privacy concerns. However, the Supreme Court has struck down a state law requiring physicians to report abortion procedures because, even though the law did not require reporting names, “the amount of information about [a patient] and the circumstances under which she had an abortion are so detailed that identification is likely,” and the information sought went beyond the health-related interests that justified reporting (Thornburgh v American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologist, 476 U.S. 474 [1986]). |

Wetterhall, 1996). The result—the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS)—now recommends that states and territories voluntarily report 56 diseases and conditions to CDC (CDC, 2003b).4 This list of nationally notifiable diseases is revised periodically.

Before transferring information on any of the diseases included in the NNDSS to CDC, states first strip the data of personal identifiers such as name, address, and social security number. For example, all states send AIDS and name-based HIV case reports to CDC using an alphanumeric code (Soundex code) derived from the person’s last name and other identifying information (e.g., six-digit date of birth, and status of residence at diagnosis) (Schwarz et al., 2002; Nakashima and Fleming, 2003). CDC does not possess the names or other personal identifiers of reported cases (Nakashima and Fleming, 2003). CDC, in turn, analyzes the data and disseminates them on a national level and shares case counts for a much smaller group of communicable diseases with the World Health Organization. Data transfer from the state to national and international levels is computerized, while data transfer from practitioners and local health departments to state health departments occurs through mail, fax, phone, and computer.

Some categorical public health prevention programs funded primarily by CDC,5 including childhood immunizations, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and HIV/AIDS, make reporting a condition of federal funding. In these cases, CDC collects from states more detailed information on the disease, for example, on the probable route of exposure (for AIDS), treatment histories (for tuberculosis), or vaccine histories (for most vaccine-preventable diseases). Local health department staff usually complete these forms after reviewing patient records.

AIDS AND HIV CASE REPORTING

AIDS case reporting has been the cornerstone of efforts to monitor and track the HIV epidemic. Soon after the first cases of AIDS were reported by the CDC in June 1981 (CDC, 1981), state health departments began to require physicians and hospitals to report by name each newly diagnosed case. In the epidemic’s early years, surveillance entailed not

only enumerating and mapping cases but also investigating commonalties for which there was no etiological explanation. By the end of 1983 most states required AIDS cases to be reported to public health officials (IOM and NAS, 1986). The system of AIDS reporting evolved over time, primarily through changes in the case definition to reflect growing clinical understanding of the disease and development of appropriate laboratory tests (CDC, 1985, 1987, 1992, 1999). All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and territories report AIDS cases by name using standardized data collection, case definitions, case reporting forms, and computer software (Nakashima and Fleming, 2003). (See sample Adult HIV/AIDS Confidential Case Report form, Annex 3-1.)

AIDS surveillance has been broadly accepted by the community of individuals living with HIV and AIDS. The relatively short time that existed in the past between diagnosis of AIDS and death and the need for health and medical services offset the risks of surveillance (Gostin et al., 1997).6 Due in large part to federal investments in state and local surveillance and strong active surveillance efforts, AIDS case reporting is among the most complete of all reportable diseases and conditions (Doyle et al., 2002).

AIDS, the most advanced stage of HIV disease, develops in the absence of treatment an average of 10 years following initial infection (Pantaleo et al., 1993). Advances in treating HIV disease have extended that window even further and may prevent some people with HIV infection from ever developing AIDS. Thus, data from the AIDS case reporting system, while still important, have become less informative about current trends in HIV transmission (CDC, 1999).

Following the development of the first antibody test for HIV in 1985, states began to initiate reporting of HIV infection. The first successful efforts to mandate HIV case reporting occurred in Minnesota and Colorado in 1985. In contrast to the “relative ease” with which AIDS reporting was implemented (Bayer, 1989), HIV reporting “ignited a firestorm of community protest” (Gostin et al., 1997). Although very few breaches of security had occurred resulting in the release of unauthorized data from the AIDS surveillance system since 1981 (Nakashima and Fleming, 2003), many civil libertarians and gay-rights organizations were strongly opposed to name-based reporting of HIV infection because they did not trust the government to safeguard such information, and were concerned

about invasion of personal privacy and discrimination in employment, housing, and insurance (Gostin et al., 1997).

Public health authorities justified reporting of HIV infection on several grounds. Reporting would alert public health officials to the presence of individuals with a lethal infection; would allow officials to counsel them about what they needed to do to prevent further transmission; would assure the linkage of infected persons with medical and other services; and would permit authorities to monitor the incidence and prevalence of infection. In the following years, CDC continued to press for name-based reporting of HIV cases, supported by a growing number of public health officials. Indeed, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists adopted several resolutions between 1989 and 1995 recommending and encouraging that states consider the implementation of HIV case reporting by name (CSTE, 1997). Political resistance persisted however, and HIV cases typically became reportable by name only in states that did not have large cosmopolitan communities with effectively organized gay constituencies or high AIDS caseloads. By 1996, although 26 states had adopted HIV case reporting, they represented jurisdictions with only approximately a quarter of total reported AIDS cases (Bayer, 1989, 1991; CDC, 1996). By October 1998, name-based reporting had a stronger foothold with 32 states then reporting cases of HIV by name, although three states reported only pediatric cases (CDC, 1999).

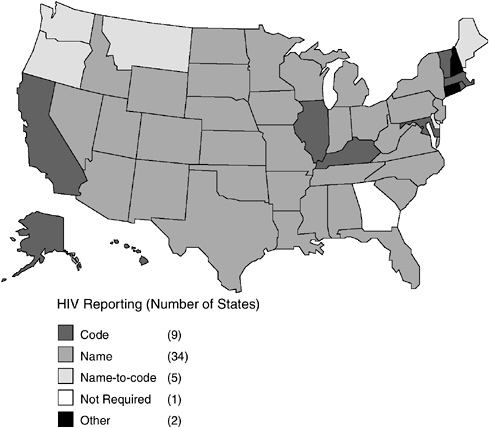

As of October 2003, all states, territories, and cities except Georgia and Philadelphia7 have implemented a confidential HIV case-reporting system (CDC, 2003a,d). Unlike AIDS case reporting, which uses a standardized name-based reporting system, states had adopted different procedures for reporting HIV cases (Figure 3-1, Table 3-1). As of October 2003, 34 states, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam had implemented the same confidential name-based reporting of HIV infection as is used for AIDS reporting and other reportable diseases and conditions. Eight states plus the District of Columbia use a coded identifier rather than the patient name to report HIV cases. Five states use a name-to-code system; initially, names are collected and then converted to codes by the local or state health department after any necessary public health follow-up. Connecticut conducts pediatric surveillance using name-based reporting but allows name or code reporting of adults/adolescents over 13 years of age. New Hampshire allows HIV cases to be reported with or without a name (CDC,

FIGURE 3-1 Status of HIV reporting in the United States as of October 2003.

SOURCES: CDC 2003a,d.

2003a,d). Of the 15 areas that use some form of code, only two use the same code. A brief case study of HIV reporting in San Francisco shows how the system works in practice (Box 3-1).

As with any surveillance system, HIV and AIDS case reporting fulfills a number of purposes. The allocation of resources appropriated through the RWCA is an example of how information collected from a case-reporting system has been used for different purposes. RWCA was structured to award grants to Eligible Metropolitan Areas (EMAs) and states that needed federal financial assistance to provide care and support services. States had enacted and implemented case-reporting systems for AIDS cases in the early 1980s and were voluntarily reporting data from those systems to CDC as part of their traditional disease-reporting activities. Therefore CDC was already receiving data on AIDS cases, albeit for a purpose independent of RWCA. Although the RWCA statute does not require that states adopt case reporting for the purpose of collecting data for the RWCA, data from such systems have been used for this purpose.

TABLE 3-1 Current Status of HIV Reporting, October 2003

|

Name-Based |

Code-Baseda |

|

Alabama (1/88) Alaska (2/99) American Samoa (8/01) Arizona (1/87) Arkansas (7/89) Colorado (11/85) Florida (7/97) Guam (3/00) Idaho (6/86) Indiana (7/88) Iowa (7/98) Kansas (7/99) Louisiana (2/93) Michigan (4/92) Minnesota (10/85) Mississippi (8/88) Missouri (10/87) Nebraska (9/85) Nevada (2/92) New Jersey (1/92) New Mexico (1/98) New York (6/00) North Carolina (2/90) North Dakota (1/88) Northern Mariana Islands (10/01) Ohio (6/90) Oklahoma (6/88) Pennsylvaniag (10/02) Puerto Rico (1/03) South Carolina (2/86) South Dakota (1/88) Tennessee (1/92) Texas (1/99) U.S. Virgin Islands (12/98) Utah (4/89) Virginia (7/89) West Virginia (1/89) Wisconsin (11/85) Wyoming (6/89) Pediatric Only: Connecticutc (1/01) Symptomatic Infection:f Washingtonh (9/99) |

California (7/02) District of Columbia (12/01) Hawaii (10/01) Illinois (7/99) Kentucky (7/00) Maryland (6/94) Massachusetts (1/98) Rhode Island (4/00) |

|

aThese states conduct HIV case surveillance using coded identifiers. Each state conducts follow-up activities to fill in gaps in the information received and longitudinally updates information on clinical status using the code. bHIV cases are initially reported by name. After public health follow-up and collection of epidemiological data, names are converted to codes. cRequires name-based reports of HIV infection in children <13 years of age. Reports HIV infection in adults/adolescents 13 and older by name or code. dAs of October 2003, Georgia had anonymous HIV reporting only and did not conduct follow-up activities on this case information. Since the release of this report, however, Georgia has implemented a name-based HIV reporting system (Georgia Division of Public Health, 2003). |

|

OTHER METHODS FOR ESTIMATING HIV PREVALENCE

Every case-reporting system has some degree of under-ascertainment. This can be due to failure of patients to present for diagnosis, failure of physicians to diagnose, failure of physicians to report, and failures within the health department itself to count cases owing to misclassification or other reasons. In addition to public health disease reporting, a number of different techniques have been designed to estimate the prevalence of disease and infections—both clinically apparent and subclinical—in a

|

Name-to-Code-Basedb |

Other |

Not Required |

|

Delaware (7/01) |

Connecticutc (1/01) |

Georgiad |

|

Maine (7/99) |

New Hampshiree (10/90) |

|

|

Montana (9/97) |

|

|

|

Oregon (9/88) |

|

|

|

Washington (9/99) |

|

|

|

eAllows HIV cases to be reported with or without a name. fAs defined in CDC classification of Group IV non-AIDS. gName-based HIV reporting was implemented in October 2002. However, HIV reporting had not been implemented in the city of Philadelphia as of October 2003. hRequires name-based reports of symptomatic HIV infection and AIDS and has a name-to-code system for reporting asymptomatic HIV cases. NOTE: States noted in italics do not have anonymous testing. SOURCES: CDC, 2003a,d. |

||

population.8 Two approaches worth consideration are seroprevalence surveys and capture–recapture methods. Seroprevalence surveys are conducted in a sample of the population of interest, and the accuracy of the

|

8 |

In this report, the Committee does not evaluate methods (e.g., Serologic Testing Algorithm for Recent HIV Seroconversion or STAHRS [Janssen et al., 1998]) for identifying incident, or new, HIV infections. Incidence is the ideal measure for understanding the dynamics, spread, and success of prevention programs. Prevalent, or known, HIV infection is appropriate for estimating the clinical burden to apportion care resources (see Chapter 5). |

|

BOX 3-1 Since 1981, California has required providers and laboratories to report by name individuals meeting the CDC’s definition of an AIDS case to local health departments, which must participate in the surveillance system. The San Francisco Department of Public Health—the local jurisdiction with the largest number of reported AIDS cases—relies on a number of activities and protocols to track the incidence of HIV and AIDS. Health care providers (or their designee, such as an office assistant or an infection control practitioner) forward a complete case report or other information that suggests that a person may have HIV or AIDS to the department. (When individuals reported with HIV progress to AIDS, providers must complete an AIDS case report form.) Staff members at the San Francisco Department of Public Health determine if the information pertains to a previously reported person with AIDS. If it does, the department adds any new information to the record. If not, a staff member visits the health care facility to examine medical records to confirm that the person meets the definition of an AIDS case. To ensure that the department’s information is as complete as possible, staff members collect information from all local health care facilities at which the patient was noted to have received care. The surveillance staff also conducts periodic reviews of medical charts to add information on subsequent opportunistic illnesses. The department actively follows up on 95 percent of notifications. Staff members assign new cases a unique city and state number and convert the person’s last name into a Soundex code before entering the data into CDC’s HIV/AIDS database. The San Francisco Department of Public Health |

results depends heavily on how representative survey participants are of the population being studied. For example, convenience samples of patients in sexually transmitted disease clinics will likely overestimate the prevalence of HIV in similar age and sex strata in the general population. Conversely, a careful random population sample, as has been done in selected geographical areas in the United States and in other countries, can provide a very accurate estimate of the overall prevalence of infection in a population.

In 1987 following pilot testing in two U.S. cities, CDC decided against attempting a random household survey of the United States to estimate HIV prevalence because of potential nonresponse bias. The agency decided instead to construct a composite estimate from various clinical populations at high risk of HIV infection, such as STD clinics, drug treatment centers, and women’s health centers. These unlinked seropreva-

|

then forwards case report forms to the California Department of Health Services with all variables except the name of the individual, and the state forwards the reports to CDC. California health and safety regulations specify that laboratories must report confirmed positive HIV tests and any HIV viral load tests to the local health department. The laboratory converts the patient’s last name to a Soundex code and sends it to the local health department along with the date of birth, gender, date, type, test results, and the name and address of the provider. The laboratory also sends this information to the health care provider, who must report the case to the local health department after adding the last four digits of the person’s Social Security number. Providers must retain a cross-reference log that links the Soundex to the patient’s name to enable health department staff to follow up. The Statistics and Epidemiology Section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health analyzes the data and presents the information to community groups and scientific meetings. The epidemiology section also publishes the results in peer-reviewed journals as well as quarterly and annual reports. Community groups, such as the RWCA Title I Planning Councils, Title II Consortia for the state of California, and HIV Prevention Community Planning Groups utilize these data for public health planning purposes. The section further augments HIV/AIDS case reporting with behavioral and other surveys among high-risk populations, with each approach using a distinct protocol and requiring staff training and monitoring. CDC and the California Department of Health Services fund the section’s 25 staff members with a budget of $2.3 million. SOURCE: San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2003. |

lence surveys were conducted using residual serum from specimens collected for other purposes (e.g., syphilis testing) (Valdiserri et al., 2000). The one portion of this “family of surveys” that provided highly accurate and generalizable results, the Survey of Childbearing Women (Pappaioanou et al., 1990), was later discontinued because of political and ethical reasons.

Another approach that has been used successfully for chronic and some infectious diseases is the capture–recapture method. A technique adapted from wildlife biology, capture–recapture consecutively samples a population, and from the proportion of individuals found in more than one sample constructs an estimate of the overall population size (International Working Group for Disease Monitoring, 1995a,b). In clinical epidemiology capture–recapture surveys most often use different patient registers or clinical records as the “samples,” and thus are largely limited to persons with diagnosed or at least symptomatic disease for

which they are seeking medical care. In the context of HIV infection, a capture–recapture scheme would enumerate patients from a variety of clinical and social services lists, such as reportable disease registries, clinic records, pharmacy records, laboratory records, and social services agency records, and compare the proportion of patients who appear on one or more of the lists. This overlap can then be modeled to estimate the size of the entire population of persons with HIV infection. This technique has been used extensively for estimating the number of persons injecting drugs in a geographical area, and for estimating the size of various populations of persons with chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cancers. CDC is currently conducting one part of its HIV surveillance evaluation study using capture-recapture techniques. Methods that make use of information on AIDS incidence and on natural history, such as “back calculation,” may also be of use; but application of such methods is more challenging than was the case earlier in the epidemic because of the impact of treatment on natural history of the disease.

An important consideration in evaluating alternative surveillance methods is the costs and benefits associated with acquiring data for use in allocating resources. The AIDS and HIV case-reporting systems have been substantially developed and are more or less in place. The primary source of funding for state HIV/AIDS case-reporting systems is from CDC, although many states, but not all, provide some additional funding (see Appendix B). For this reason, there may be a perception that the data from these systems are “free,” or at least free in the sense of low marginal cost. However, adding more missions, such as resource allocation, to an already large, expensive, and complex enterprise may have additional costs. To the extent that additional data elements bearing on the specific needs of RWCA grantees are requested, additional resources will be required.

REFERENCES

Bayer R. 1989. Private Acts, Social Consequences: AIDS and the Politics of Public Health. New York: The Free Press.

Bayer R. 1991. Public health policy and the AIDS epidemic. An end to HIV exceptionalism? New England Journal of Medicine 324(21):1500–4.

Birkhead GS, Maylahn CM. 2000. State and local public health surveillance. Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. Teutsch SM, Churchill RE, Eds. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1981. Pneumocycstis Pneumonia–Los Angeles. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 30:250–2. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 1985. Revision of the case definition of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome for national reporting—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 34:373–6. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 1987. Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 36(IS):1–15. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 1992. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 41(RR–17):1–19. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 1996. U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 1996. HIV/ AIDS Surveillance Report 8(2). Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 1999. Guidelines for national human immunodeficiency virus case surveillance, including monitoring for human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(13):1–28. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 2003a. Current Status of HIV Infection Surveillance: April, 2003. (Email communication, Patricia Sweeney, CDC, April 28, 2003).

CDC. 2003b. Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases: United States. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/epo/dphsi/phs/infdis2003.htm [accessed October 15, 2003].

CDC. 2003c. HIPAA Privacy Rule and Public Health, Guidance from CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52:1–12.

CDC. 2003d. Update on current status of HIV Infection Surveillance: April 2003. (Email communication, Patricia Sweeney, CDC, October 13, 2003).

CSTE (Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists). 1997. National HIV Surveillance: Addition to the National Public Health Surveillance System. CSTE Position Statement 1997-ID-4.

DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2003. OCR Privacy Brief. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. HIPAA Compliance Assistance. [Online]. Available: http://www.hhs.gov/privacysummary.pdf [accessed September 28, 2003].

Doyle T, Glynn K, Groseclose S. 2002. Completeness of notifiable infectious disease reporting in the United States: An analytical literature review. American Journal of Epidemiology 155(9):866–74.

Georgia Division of Public Health, Epidemiology Branch, HIV/STD Epidemiology Section. 2003. Proposal for HIV Infection Reporting in Georgia. [Online]. Available at: http://www.ph.dhr.state.ga.us/epi/hivreporting.shtml [accessed September 25, 2003].

Gostin LO. 2000. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gostin LO, Ward JW, Baker AC. 1997. National HIV case reporting for the United States. A defining moment in the history of the epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine 337(16):1162–7.

Hall MA, Bobinski MA, Orentlicher D. 2003. Health Care, Law, and Ethics. 6th ed. Aspen Publishers.

International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forecasting. 1995a. Capture-recapture and multiple-record systems estimation I: History and theoretical development. American Journal of Epidemiology 142:1047–58.

International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forecasting. 1995b. Capture-recapture and multiple record systems estimation II: Applications in human disease. American Journal of Epidemiology 142:1059–68.

IOM and NAS (Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences). 1986. Confronting AIDS: Directions for Public Health, Health Care, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Janssen RS et al. 1998. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. Journal of the American Medical Association 280:42–8.

Koo D, Wetterhall S. 1996. History and current status of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2(4):4–10.

Langmuir AD. 1963. The surveillance of communicable diseases of national importance. New England Journal of Medicine 268:182–92.

Nakashima AK, Fleming PL. 2003. HIV/AIDS surveillance in the United States, 1981-2001. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 32(Suppl 1): S68–85.

Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Fauci AS. 1993. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection . New England Journal of Medicine 328(5):327–35.

Pappaioanou M, George JR, Hannon WH, Gwinn M, Dondero TJ Jr, Grady GF, Hoff R, Willoughby AD, Wright A, Novello AC. 1990. HIV Seroprevalence surveys of childbearing women: Objectives, methods, and uses of the data. Public Health Reports 105:147–52.

Roush S, Birkhead G, Koo D, Cobb A, Fleming D. 1999. Mandatory reporting of diseases and conditions by health care professionals and laboratories. Journal of the American Medical Association 282(2):164–70.

San Francisco Department of Public Health. 2003. How HIV reporting works in San Francisco. (Email communication, Sandra Schwarcz, SFDPH, May 13, 2003).

Schwarcz S, Hsu L, Chu PL, Parisi MK, Bangsberg D, Hurley L, Pearlman J, Marsh K, Katz M. 2002. Evaluation of a non-name based HIV reporting system in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 29:504–10.

Thacker SB. 2000. Historical development. Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. 2nd ed. Teutsch SM, Churchill RE, Eds. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valdiserri RO, Janssen RS, Buehler JW, Fleming PL. 2000. The context of HIV/ AIDS surveillance. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 25(Suppl 2):S97–S104.