14

Economic Challenges to American Manufacturing: A Labor Perspective

Ron Blackwell

AFL-CIO

American manufacturing, particularly from a laborer’s point of view, is in crisis. Approximately 54,000 new manufacturing jobs were lost in February 2003. That was the 30th consecutive month of lost jobs in manufacturing. At this point, manufacturing employment numbers in the United States are the same as they were in 1961. The question is whether we can do everything that we want to do as a nation, employing that number of people in manufacturing products for the nation and the world. An analogy is often made between the transition from agriculture to manufacturing and the transition from manufacturing to services. There is an important difference between these two transitions, however. The United States is an agricultural-product-exporting nation. Agricultural products are one of our most successful exports. The manufacturing sector, in contrast, is currently undergoing a trade deficit of nearly 5 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), with no signs of improving.

Manufacturing is an important industry for many states, and manufacturing activity is spread diffusely across the country. The question is whether or not, if the current economic course is held, the United States will continue to have the manufacturing base that it needs. From the labor point of view, the answer is, absolutely not.

EMPLOYMENT TRENDS IN MANUFACTURING

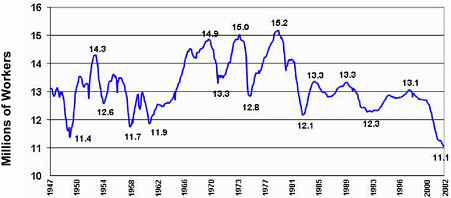

There was an enormous burst in employment of manufacturing production workers in the 1960s (Figure 14-1). Before that, in the 1950s, and after that, in the 1970s, there were ups and downs, but employment remained fairly stable. During the 1979 recession, there was a sharp decline in the number of production workers, which continued through the early 1980s. At that time, actions by the Federal Reserve Board drove interest rates up, drove the value of the dollar up, and drove manufacturing straight down in terms of employment. The U.S. manufacturing industry did recover somewhat in the 1980s. However, the most recent recession, between 2000 and 2003, although it has been fairly short and shallow for the economy as a whole, has been devastating for manufacturing. It is nothing less than a depression in American manufacturing, rural or urban distinctions aside.

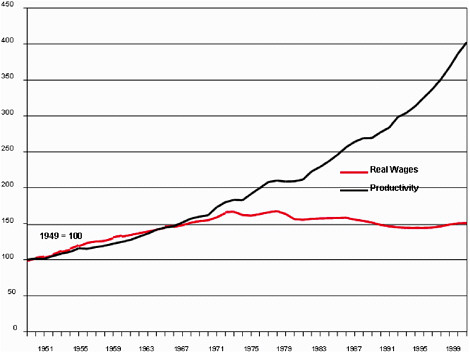

The relationship between manufacturing productivity and wages is an important one for the American labor movement. Two important phases can be distinguished in the postwar period (Figure 14-2). From 1949 to 1973, there was rapid economic growth and rapid productivity growth, with rapid wage growth matching productivity growth step by step. The American middle class was built during this period when real family incomes doubled. There has never been such a growth in the living standards of people in the history of the world. Since the early 1970s, however, manufacturing growth has slowed and wages have actually fallen. An enormous gap has opened up between the productivity of American workers, still the most

FIGURE 14-1 Number of production workers employed by the U.S. manufacturing sector, 1947 to 2002. SOURCE: Department of Labor.

productive manufacturing workers in the world, and the wages that they earn.

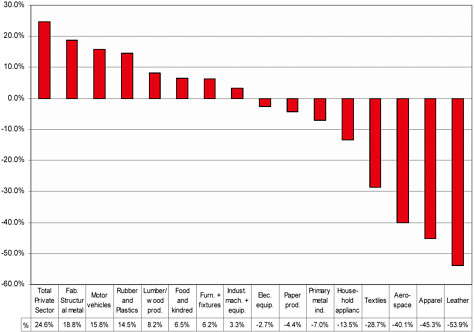

This gap is one of the labor movement’s most serious concerns, along with maintaining production. Workers in the manufacturing sector earn on average $24.30 per hour, in comparison with $22.06 per hour for workers in non-manufacturing sectors and $19.74 for workers in the service sectors.1 Within manufacturing jobs, there is a considerable advantage to being in a union, because both wages and benefits are higher for workers represented by a union.2 Unfortunately, there is a declining union density and varying amounts of union representation in most industrial sectors.3 This declining power of worker representatives in manufacturing has caused the gap to open up between compensation and productivity. In addition, over the past decade there have been significant changes in production workers across industries (Figure 14-3).

SHORT-TERM, CYCLICAL CHALLENGE

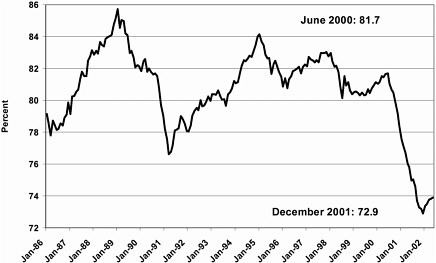

The current recession is not like any previous postwar recession. It was not caused by the Federal Reserve Board acting to stamp out inflation. Rather, this recession was caused by a decrease in business spending, especially in manufacturing, following an overinvestment in manufacturing during the 1990s. The decline in production during this recession caused capacity utilization to dive from 81.7 percent in June 2000 to 72.9 percent in December 2001 (Figure 14-4). Between March 2001 and December 2002, manufacturing employment dropped from 12.3 million to 11 million. This decrease of 1.3 million production workers represents over 90 percent of all jobs lost during this recession. The recession is therefore a manufacturing-driven phenomenon. The decrease in business spending in the manufacturing sector has brought the entire economy into a recession and has created a short-term crisis in the

|

1 |

Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, and Heather Boushey. 2003. The State of Working America, 2002/2003. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. |

|

2 |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor. Available at http://www.bls.gov. Accessed November 2003. |

|

3 |

Kate Bronfenbrenner and Robert Hickey. 2002. Overcoming the Challenges to Organizing in the Manufacturing Sector. Unpublished report submitted to the AFL-CIO. |

FIGURE 14-2 Manufacturing productivity and real-wage indices, 1949 to 2000. SOURCE: Department of Labor.

manufacturing sector.

The short-term, cyclical challenge that we face is a manufacturing-led recession with what I will call a manufacturing-constrained recovery. Before we can solve the short-term problems faced in this recession, it is essential to deal with the problems of manufacturing. In particular, it is essential to deal with the problems of manufacturing capacity, because manufacturing constraints will be reached before the economy recovers.

There has been a lot of discussion about economic growth and President Bush’s plan for stimulating the economy. The American labor movement disagrees with the predicted economic impact of this plan. The economy is more open than in earlier recessions, with imports and exports as a percentage of national income being much higher. Therefore, if the government spends money now, in the form of new government spending or tax increases, a large part of the money will be spent on goods not manufactured in the United States. The same initial expenditure will not result in the same stimulus as before. If we try to expand the economy without dealing with manufacturing problems, politically unsupported levels of budget deficits will be generated long before there is any traction in labor markets.

LONG-TERM, STRUCTURAL CHALLENGE

The two major imbalances that existed in the economy going into this recession were private sector debt, which will not be addressed here, and the trade deficit. The trade deficit

FIGURE 14-3 Change in employment of production workers across different industrial sectors, 1989 to 2000. SOURCE: Economic Policy Institute and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

represents an enormous imbalance in our external accounting, nearing 5 percent of the GDP last year. Such a trade deficit would shake the currency of any country except the United States. This trade deficit is entirely the result of the balance of trade in manufactured goods. Each day, the United States borrows $1.3 billion to pay for the goods that are consumed here but not produced here. When this money isborrowed, the interest must be paid. In 2001, the United States owed $2.3 trillion, or close to 23 percent of the GDP, from this practice of consuming beyond our means. By 2006, unless these policies and practices are changed, it is estimated that the United States will have built up a debt equal to 40 percent of the GDP.

This is the long-term, structural challenge that the United States is facing. There are several ways of responding to this challenge. One option is to continue to borrow indefinitely, which is how the politicians in Washington, D.C., seem to treat this problem. The second option is to consume less. We may be forced to do this if other countries won’t continue to lend us the money to buy these things. The third, and preferred, option is to produce more so that we can pay for the goods that we consume and support a higher standard of living. Maintaining the standard of living of the United States therefore depends directly on what we do or fail to do about manufacturing.

LABOR’S STRATEGY

To deal with both of these challenges, labor’s strategy is to join the campaign to restore the industrial base of the United States. In this sense, labor shares the perspective of the

FIGURE 14-4 U.S. manufacturing capacity utilization, January 1986 to May 2002. SOURCE: Federal Reserve Board.

National Association of Manufacturers, although there is probably little agreement on the means by which this should be accomplished. In addition, as the American labor movement, it is important to recognize the need to organize the workers that remain in American manufacturing industries. Unless the workers are organized, the gains from increased manufacturing productivity won’t be distributed very broadly.

There was a time in the 1960s when, even in modest industries such as apparel, manufacturing production workers, for example sewing machine operators, were at least 50 percent more productive than their competitors internationally. American workers are the most productive workers in the world, and yet they don’t earn enough in this industry to support a family above the poverty level. The reason for this is that these industries have been hit by international competition. American workers are put in direct competition with some of the most oppressed, impoverished, and exploited workers in the world in a trade regime that neither respects nor protects either workers’ rights or human rights. New changes in manufacturing technologies allow this fundamental imbalance to take place. Unless policies are found to address this issue, there is no solution to the problem of manufacturing going forward.

At that time, companies in Japan were competing with companies in the United States, and it was a challenge for America and for American competitiveness. Eventually, however, this trend progressed from the textile and apparel industry into the electronics, automobile, and most other manufacturing industries. Many companies then made the decision to outsource. Now we are in a situation where manufacturing is still going on, it’s just not going on in the United States. From a labor perspective, the health of the companies is important because the welfare of our members depends on the success of these companies. However, these companies can compete with each other in different ways. They can compete in what I will call “high-road”

ways, in which everybody benefits, including the people that work for them and the country itself. Or they can compete in “low-road” ways, in which the only winners are the shareholders or the chief executive officers. Manufacturing companies today are under tremendous pressure from a variety of sources, including increased competition in the product markets. For domestic industries, this pressure may have come about as a result of deregulation and privatization of services and goods. In the manufacturing industry, however, the real challenge has come from the internationalization of production. Labor urges that manufacturing companies face this competition in high-road ways.