5

Environmental Issues in Health Care Design

Derek Parker

Today I am going to address improved indoor environmental design of health care facilities and discuss the research agenda that has been developed by the Center for Health Design, a not-for-profit research and advocacy organization that I helped found about 15 years ago. In this regard, I would like to call your attention to a recent publication of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the third in a series that began with To Err is Human, followed by The Quality Chasm, and which now adds Keeping Patients Safe. I believe this is the first time that IOM has treated the built environment as a legitimate treatment modality, which is a major step forward for those of us interested in the physical environment and its relationship to health and well-being.

A legitimate question to ask in this time of crisis in health care is why any health care administrator should spend any time at all thinking about the built environment. When they are dealing with severe staffing shortages, declining revenues, poor balance sheets, and falling bond ratings, why spend any time at all thinking about issues in the built environment?

The answer to that, essentially, is only if we can show return on investment. From its inception, that is what the Center for Health Design has tried to do—to promote design in health care facilities that supports positive health outcomes in a moral, ethical, and sustainable manner.

We know from our experience, though, that we have not been heard very well. So over the past five years we have taken that message one step further and looked at what happens to the bottom line of organizations in a struggling sector that takes the built environment seriously.

The Center for Health Design serves and enables a worldwide network of 25,000 physicians, nurses, interior designers, architects, and researchers with an interest in the physical environment and health outcomes. In establishing the center, we were very much influenced by Leland Kaiser’s work: he believed that the hospital, as a human invention, could be reinvented at any time. In this regard, we have done a great deal of thinking about the services that patients need versus what they want. Hospital patients need to be where they are. A hospital is not a resort where people choose to come. It is a place where they come when they need care, a time of considerable stress.

For the past five years, the center has been developing a research agenda. We call the research projects “pebbles” because one of our board members visualizes throwing a pebble into a pond and seeing if the research results would ripple through the industry. It appears that this is beginning to happen.

First, understand that patients speak a different language than caregivers. Patients must resort to visual clues to assess the level and quality of care they receive. In essence, they become detectives who must sift through the

torrent of clues that facilities provide about the quality of the care and the philosophy and caring attitude of the organization.

Every building tells a story. It also communicates to the staff what management thinks about their safety and welfare. A 1999 study from the IOM found that “…serious and widespread quality problems exist throughout American medicine. These problems…occur in small and large communities alike, in all parts of the country, and with approximately equal frequency in managed care and fee-for-service systems of care. Very large numbers of Americans are harmed as a result…” This indicates that we have a very serious problem in this country that may be as bad or worse elsewhere. Very large numbers of Americans are harmed as a result of what is essentially a system design failure within our hospitals. The IOM stated that between 48,000 and 94,000 Americans die preventable deaths every year in American hospitals.

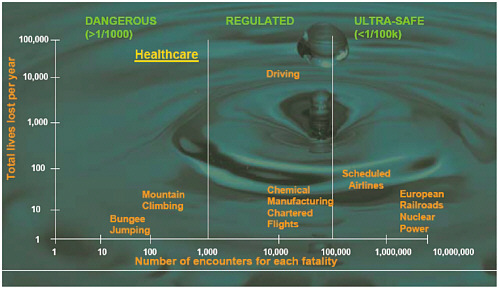

Figure 5.1 shows where interaction with the health care system rates as a hazardous activity. On a perinteraction basis, it is almost as dangerous as bungee jumping and mountain climbing and, because of the much higher participation rates, claims a thousand times more lives annually. Obviously, there is a very serious quality and safety issue in our hospitals.

David Lawrence, chairman of Kaiser-Permanente, has said that in his organization he is going to reduce costs by improving quality. I believe that is a worthy and achievable goal.

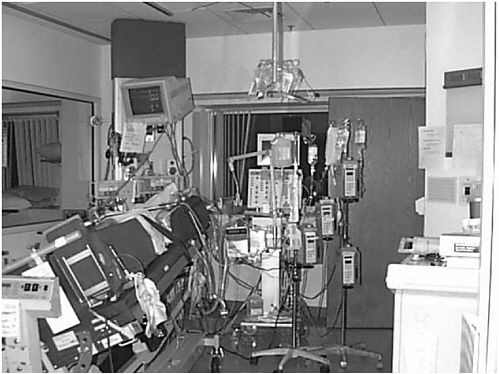

Figure 5.2 could be taken in almost any hospital in the United States today, and, as you’ll note, it is very difficult to find the patient amid all the clutter. The photo could not have been taken in any other country because only in American hospitals is so much equipment so readily available. It is no wonder that systemic failure is such an issue.

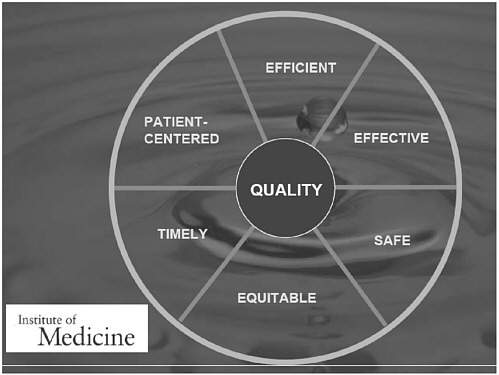

Figure 5.3 shows the six domains from the IOM study that we at the Center for Health Design have taken very seriously. We try to look at the components of the physical environment for each of those six domains. Colin Martin expressed this idea well in Lancet: “Although the premise that physical environment affects well-being reflects common sense, evidence-based design is poised to emulate evidence-based medicine as a central tenet for healthcare in the 21st century.” Unfortunately, this concept is not, at the moment, mainstream, but we are gradually beginning to see a relationship develop between evidence-based design and evidence-based medicine.

FIGURE 5.1 Fatality rates for various activities.

FIGURE 5.2 Typical treatment room in a U.S. hospital.

In support of the Center for Health Design, Haya Rubin of Johns Hopkins University, was retained to do a literature search on the relationships between the built environment and medical outcomes. From almost 80,000 studies she found only 84, less than one-tenth of 1 percent, that actually met any criteria for inclusion in the database. There is just not very much in the way of data or analysis to document these relationships. It was just this lack of documented evidence that led the center to initiate several projects. We had several objectives in beginning this work: to develop a research model that would produce documented research examples, to start a dialogue on the results, and to create a ripple effect through the industry. That is now happening.

CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL HEALTH CENTER

Children’s Hospital Health Center in San Diego was the Center for Health Design’s first “pebble.” From that beginning, we now have 18 projects around the country as shown below:

-

San Diego Children’s Hospital

-

Karmanos Cancer Institute

-

Clarian Methodist Hospital

-

Bronson Methodist Hospital

-

Southwest Washington Memorial Hospital

-

St. Alphonsus Regional Medical Center

FIGURE 5.3 The six domains of health care quality.

-

Weill Cornell Medical Center

-

Froedtert Hospital

-

Parrish Regional Medical Center

-

Scott and White

-

Yavapai Medical Center

-

Sitrin Health Care Center

-

M. D. Anderson

-

Peace Health Oregon Region

-

Columbia-St. Mary’s

-

Affinity Health System

-

Bethesda Hospital

-

Banner Estrella Medical Center

These facilities are quite diverse and include women’s and children’s hospitals, cancer and cardiac specialty centers, and long-term care facilities. These projects are all being driven by senior management—the chief medical and administrative officers who want to know more about how to use the physical environment as a legitimate treatment modality.

Representatives of these 18 institutions now come together twice a year to meet and share successes, frustrations, and data in an open exchange. Nothing is secret. Stress on patients, their families, and the staff has been an important focus. We are facing a very serious staff shortage in American health care at every level, but particularly nurses, and all indications are that the situation is going to get worse before it gets better.

The research agenda has been divided into five areas: access to nature, degree of personal control, the use of positive distractions to reduce stress, social support for the patients, and environmental stressors.

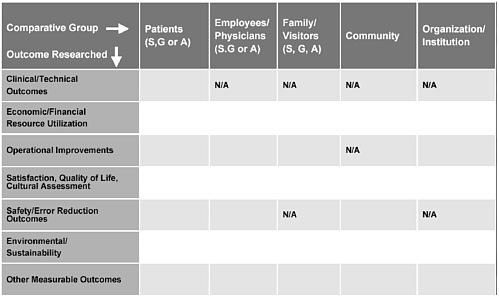

We have identified multiple factors in each of these areas where we think the built environment has something to contribute. Measurement is a critical issue so that the data are meaningful and reproducible. Jim Varni, of the Center for Child Health Outcomes at Children’s Hospital in San Diego, designed a matrix to arrange the data so that we can understand and communicate the results. The PedQL™ Inventory captures clinical outcomes, financial outcomes, and satisfaction outcomes at the level of a single patient, groups of patients, staff, visitors, and family.

CONVALESCENT CARE HOSPITAL

Convalescent Care Hospital seemed like a good pebble because it is a unique specialty facility. It houses 60 very fragile children who are in long-term care, all of whom are in wheelchairs, and many are blind. Even every wheelchair is different, designed specifically for the needs of a particular child. Many children have suffered abuse or accidents that caused brain damage, such as near-death drownings.

They are currently housed in a building designed for acute care adult patients, which is a totally inappropriate environment. Moving them into a new building specifically designed around their needs will give us the opportunity to observe how the same patients, with the same caregivers, families, and services, react to a change in the environment. That seemed like a great opportunity to collect some pre- and postrelocation data.

Changes in organizational behavior as the organization moves from the existing building to the new building will also be measured. We are now talking about changes in that behavior in the present building that we can put in place, try out, and move into the new building.

As an example of providing more control for patients and their families, we redesigned the wheelchair storage. Every child has a wheelchair that is now stored in the corridors, creating a safety hazard. We thought we would put garages in the corridors, so people could put their wheelchairs away, but the parents didn’t like that. They think of that wheelchair as being a very personal extension of their child, and they wanted it in their control within the child’s room. So we just reversed the garages, so that they are only accessible from the room. One mother looking at the plan said, “I like the concept, but I don’t see anywhere where I can take my child out of the room, be out of the way but not isolated, and hold her in her fuzzy red pajamas and read her a story.”

That stuck with us. So we went through the plans and found that by doing some very simple things, such as changing the door swing, moving a column, modifying some lighting, and so on, we were able to create half a dozen “fuzzy red pajama” spaces in the building without changing the cost of the building or the program.

BRONSON METHODIST HOSPITAL

The second pebble was Bronson Methodist Hospital, a new building in Kalamazoo, Michigan, that was also referenced in the IOM study. This was a large project, costing over $180 million. It incorporated features such as access to nature, enhanced personal control, positive distractions, and a stress-reducing environment. Metrics included employee turnover, before and after, patient outcomes, length of stay, cost per unit of service, waiting time, patient satisfaction, and organizational behaviors.

Some of the early results are as follows:

-

7 fewer nosocomial infections per 1,000 patients,

-

Savings due to fewer patient transfers,

-

1 percent market share increase,

-

80 percent occupancy rate since opening (5 percent increase),

-

Nurse turnover rates below 12 percent,

-

Increased employee satisfaction, and

-

Patient satisfaction 95.2 percent.

Just reducing the nosocomial infection rate saved $300,000 per year. The hospital has done very good environmental surveys that correlate very well across the board, and the staff believe they are providing a much better level of care.

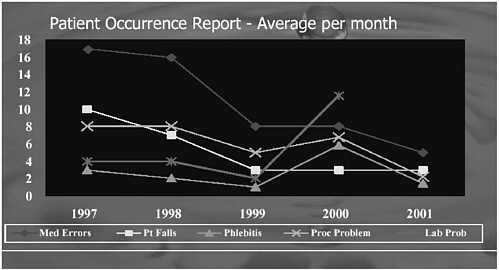

FIGURE 5.4 Selected health data, Clarian Methodist Hospital.

CLARIAN METHODIST HOSPITAL

The next project is Clarian Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis, which is also referred to in the IOM study. This was a small project, a comprehensive cardiac care unit essentially managed and run by a wonderful lady named Ann Hendrick. Clarian wanted to measure clinical outcomes, patient and staff satisfaction levels, education and personal growth, and cost and efficiency improvements.

One immediate result was that patient falls decreased 75 percent. This is important because patient falls are a very serious issue in hospitals. The average cost of a patient fall that is not litigated is about $10,000 for increased length of stay, increased medication, repairing broken bones, and so on. Data also show that patients who fall in hospitals actually die three months earlier than people who do not fall because they are afraid of falling a second time and become more tentative. This changes their lifestyle, they become less active, and their health just seems to spiral downward.

Figure 5.4 is a chart from Clarian that compares the incidence of medical errors, patient falls, phlebitis, lab problems, and process problems after moving into the new facility in 1999. What caused falls to decrease? The hospital built much larger rooms than are typical, so that a visiting family has a place to stay and be with the patient in the room on a routine basis. The presence of additional hands and eyes with the patient was all that was needed. This was a serious if novel approach to the issue of patient falls that produced positive results.

Patient transfers were reduced substantially by, again, going to all single-patient rooms. The quality of communication between the caregiver and the patient improved dramatically when the patient was in a single room. Physicians don’t feel that they have to whisper or talk in riddles because they don’t want someone else to overhear.

Figure 5.5 is the matrix we are using to structure the data collection effort for all 18 pebble projects. Our next step will be to generate more pebbles to see if we can replicate some of these findings.

Why is all this so important? In this country alone, we are currently spending $15 billion a year in capital expenditures for health care facilities, and that is expected to rise to $25 billion by 2010. Now is the time to build a business case for better health care facilities and a logical case for evidence-based design.

FIGURE 5.5 Pebble project research matrix.

I would like to close with the example of what I call Fable Hospital. None of the data is invented, all are based on the early findings of our pebbles. What is hypothetical is that everything occurs in one place at one time.

Fable Hospital is a 240-bed regional open medical center, estimated to cost $240 million or $1 million per bed, which is about right. Our best work results when our clients provide value-driven leadership. Therefore, high values for quality, safety, patients, family, and staff, attention to cost, and community responsibility are assumed.

Fable Hospital would be a place of tranquility. Our design innovations included large oversized windows to provide lots of natural light in single rooms set up for variable-acuity patients. Variable acuity means that the patient can be admitted to one room and, for the most part, stay in that room under varying health conditions before being discharged. The benefit of variable-acuity rooming is related to the fact that the error rate increases 75 percent every time a patient is moved: Sometimes the data stay with the patient but oftentimes they do not.

Fable Hospital would have decentralized, barrier-free nursing stations. With such stations the nurses are closer to the patients, which results in fewer patient falls because the nurse is with the patient instead of running around finding supplies and other things. Video evidence from Clarian Methodist showed that in a 12-hour shift the nurses were actually with each patient for 20 minutes. The rest of the time they are fetching and carrying and running around and reporting and writing and on the telephone and so on. They generally are not providing patient care. That is one of the reasons we found such low satisfaction rates for nurses. They are not doing what they joined the profession to do.

Art, music, and gardens are receiving additional attention. A children’s hospital we are working on in Chicago has a poet in residence to spend time in the hospital, writing poetry, working on poetry with the children, and posting the “poem of the day” on a number of bulletin boards around the hospital. Additional consultation spaces are provided so that patients can have direct access to the caregivers and receive information so that they know what to do, as can the family members.

The estimated cost of all the added design features is $12 million, or 5 percent of the total project cost. The expected benefits of that additional expenditure are shown in Table 5.1. There is an estimated first-year cost

TABLE 5.1 Fable Hospital: First Year Financial Impacts of Design Features.

|

Design Feature Impacts |

Financial Impacts |

|

80% reduction in falls |

$2,452,800 in savings |

|

80% reduction in transfers |

$3,893,200 in savings |

|

Decrease in nosocomial infections |

$80,640 in savings |

|

Reduction in nursing staff turnover |

$164,000 in savings |

|

16.4% decline in use of pain medication |

$1,216,666 in savings |

|

1.5% market share increase |

$2,168,100 increase in revenue |

|

Increase in philanthropy |

$1,500,000 increase in revenue |

|

Total |

$11,475,406 in savings and increased revenue |

savings of $7.8 million. On the revenue side, based on actual experience with real hospitals, we conservatively estimated almost $3.7 million from increased market share and philanthropy. The total of savings and increased revenue in the first year alone ($11.5 million) essentially covers the cost of a vastly superior design.

All of the savings described are drawn from the Center for Health Design’s pebble projects (http://www.healthdesign.org). No one has yet achieved this level of improvement, but we are all trying. I would like to be the first to design a real Fable Hospital.

The moral of this fable is that illness is expensive, but well-being pays dividends. Investment in better buildings pays off directly and indirectly, and we are getting close to being able to prove that. We must. Our resources are finite, and our health care system is terribly inefficient. We have to maximize value, and I am committed to using evidence-based design instead of the status quo.

ABOUT THE PRESENTER

Derek Parker is chairman of Anshen+Allen Architects and president of a renewable energy company, Medergy. He has more than 40 years of experience focused on the planning and design of health care and academic research facilities. Mr. Parker has made significant contributions to health care and university architecture in the United States, as well as nine technologically and culturally diverse nations including the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, the Peoples Republic of China, the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Japan, Italy, and the Philippines. He is a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and numerous architecture and design review boards. Mr. Parker also serves as an adjunct professor at the University of Hawaii and as a board member of the Center for Health Design.