D

Letter Report

November 15, 2004

David Garman,

Assistant Secretary

Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

U.S. Department of Energy, EE-1 FORS

1000 Independence Avenue, S.W.

Washington, DC 20585

Mark Maddox,

Acting Assistant Secretary

Office of Fossil Energy

U.S. Department of Energy, FE-1 FORS

1000 Independence Avenue, S.W.

Washington, DC 20585

RE: Methodology for Estimating Prospective Benefits of Energy Efficiency and Fossil Energy R&D

Dear Mr. Garman and Mr. Maddox:

From the time the Department of Energy (DOE) was formed in 1977, successive administrations in Washington, D.C., have looked to technological innovation as a critical tool for ensuring that the nation has affordable, clean, and reliable energy. To help stimulate this innovation, DOE, since its inception, has invested about $29 billion on energy efficiency and fossil energy research and development (R&D).1 Looking ahead, innovation continues to be a centerpiece of energy policy. Indeed, visions of a hydrogen economy and zero-emission coal power plants have increased the importance of energy R&D relative to other national priorities.

Evaluating government investment in such programs requires assessing their costs and benefits. Doing so is not a trivial matter. For example, the analysis of costs and benefits must reflect the full range of public benefits—environmental and security impacts as well as economic effects. In addition, the value of government funding for a particular project depends on what might happen if the government did not support the project. Would some private entity undertake it or an equivalent activity that would produce some or even all of the benefits of government involvement? These thorny issues arose in a retrospective evaluation of government programs undertaken by the National Research Council (NRC) and published in a report in 2001.2 Together with a number of other methodological problems, they appear as well in the evaluation of prospective investments in energy R&D.

At the request of the Congress, the NRC formed the Committee on Prospective Benefits of DOE’s Energy Efficiency and Fossil Energy R&D Programs (“the committee”; see the roster in Appendix A), which is currently developing a methodology for the prospective evaluation of benefits of government-funded energy R&D. Unlike the retrospective study, this methodology could be used to evaluate program management and funding decisions on an ongoing basis. This project is expected to be completed with the issuance of an NRC report in early 2005. At the request of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior and Related Agencies, this letter report3 is being provided before the conclu-

sion of the study. It satisfies the subcommittee’s request, transmitted to the NRC on July 21, 2004, to “provide an overview of the study committee’s methodological approach; how that approach differs from the retrospective study delineated in the Academies’ report …; and what is expected to be contained in the committee’s final report.”

This letter report begins with a summary of the context of the prospective benefits study. It then discusses the main characteristics of the prospective methodology. The final report is discussed in the section “Contents of the Phase 1 Final Report,” below.

CONTEXT OF THE PROSPECTIVE STUDY

Recognizing the importance of technological innovation, the Department of Energy, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and Congressional appropriations committees have given increasing attention to understanding the effectiveness of federal funding of applied energy R&D. The conference report of the Consolidated Appropriations Act4 for fiscal year (FY) 2000 requested that the NRC assess the benefits and costs of DOE’s R&D programs in fossil energy and energy efficiency5—a task agreed upon by the House and Senate subcommittees with jurisdiction over the funding of these programs.

Completed in 2001, the retrospective study conducted by the NRC reported that, in the aggregate, the benefits of federal energy R&D exceeded the costs, but it observed that the DOE portfolio included both striking successes and expensive failures. As important, the NRC study noted that the methodologies by which DOE had calculated the benefits of its programs varied considerably, thus making comparisons of program benefits difficult. The committee that carried out the retrospective study, the Committee on Benefits of DOE R&D on Energy Efficiency and Fossil Energy, developed and applied its own uniform methodology for assessing the benefits of energy R&D programs. This methodology was, however, limited to a retrospective analysis of the results of completed R&D programs.6

The Congress continued to express its interest in R&D benefits assessment by providing funds for the National Research Council to build on the retrospective methodology in order to develop a methodology for assessing prospective benefits.7 Funds were made available for this purpose in both FY 2003 and FY 2004. In response, the NRC began a project in two overlapping phases for the development of a prospective benefits methodology. The current study, which is the first of these phases, began in December 2003 and is expected to be completed in early 2005. The second phase will begin in early 2005. It is expected that the Congress will fund subsequent phases. The statement of task assigned to the committee for Phase 1 is as follows:

Adapt the results of the previous committee with an aim to develop a methodology and matrix for evaluating prospective benefits of DOE’s energy efficiency and fossil energy programs. In addition, the committee will apply its newly developed methodology to evaluate energy efficiency and fossil energy programs.

Two considerations are particularly important in the formulation of this task. One is that the committee is to build on the work of the retrospective study and, by extension, on the work of DOE and OMB that has taken place since the retrospective study was completed. OMB has made considerable progress in creating tools for assessing the value of future energy R&D investments and has promulgated specific investment guidelines for applied R&D as well as for more basic research programs.8 OMB also began the evolutionary development of the Program Assessment and Rating Tool (PART), which ranks programs on the basis of both their likely benefits and the quality of program design and management.9 One of the first applications of PART was to the applied energy R&D programs. OMB now makes public its summary assessments of major DOE programs.10

DOE has also made important strides in developing tools for assessing the likely benefits of its R&D programs. While the final report of this committee will comment in more detail on DOE’s work, it is important to note here that elements of the Department—and particularly the fossil energy and energy efficiency programs—have worked together toward common methodologies and approaches. The scale of DOE’s effort has been impressive, involving substantial staff com-

|

|

or recommendations, nor did they see the final draft of the report before its release. The review of this report was overseen by John Ahearne, NAE, Sigma Xi, and Larry Papay, NAE, Science Applications International Corporation (retired). Appointed by the NRC, they were responsible for making sure that an independent examination of this report was carried out in accordance with institutional procedures and that all review comments were carefully considered. Responsibility for the final content of this report rests entirely with the authoring committee and the institution. |

mitments and the extensive use of sophisticated economic models.

As this committee has studied these developments in methodology, it has become increasingly clear that the methodology developed by the committee should build on the advances in DOE’s analytic capability while at the same time building on the virtues of the simple retrospective methodology. The committee’s work will be most useful if it helps move the entire enterprise toward a common methodology that assists decision makers at every level to consider “what programs should be continued, expanded, scaled-back, or eliminated.”11

The second important consideration in the formulation of the statement of task is that the committee must develop not only a methodology that is rigorous in its calculation of benefits and assessment of risks, but also a process for applying that methodology in practice in a consistent manner across a variety of DOE programs. The process itself needs to include the participation of outside experts who are familiar with the specific technologies and markets involved and can provide an independent assessment of the programs. Familiarity with the programs, technology, and industry is critical to determining what needs to be considered in the analysis, to assessing the likelihood of achieving the technical goals, and to calculating the benefits if a program is successful. The process of assembling and applying expert panels efficiently within the constraints of a consistent analytic methodology is thus central to the committee’s work.

To carry out Phase 1 of its assigned task, the committee organized the project into the following steps:

-

Review methodologies for assessing R&D benefits developed by DOE, OMB, and other agencies.12

-

Propose a conceptual framework that expresses the outcome of the assessment of the various methodologies.

-

Propose a methodology for implementing the framework.

-

Appoint expert panels to apply the methodology to three DOE programs.13 Committee members chair each of these panels, but the panels will be composed mainly of persons with expertise in the technology and markets involved in the programs.

-

Receive reports from each panel.

-

Evaluate the experience reported by the panels and modify the methodology accordingly.

-

Present the committee’s conclusions in a final report. The Phase 1 report will also contain recommendations for specific steps to be taken in Phase 2 of this ongoing NRC effort.

The committee proposes using a conceptual framework that builds on the framework of the retrospective study, modified for prospective use. The benefits matrix was accepted as a useful framework for discussing benefits retrospectively, and the committee believes that a similar matrix should play a parallel role for prospective benefits. The prospective matrix that the committee intends to use is discussed in the following section.

This study is intentionally designed, however, to provide the expert panels considerable flexibility in applying the methodology for completing the matrix. It is the judgment of the committee that this approach will stimulate critical thinking about the methodological details, thus helping to refine the methodology that will ultimately be proposed. In addition, the use of expert panels is an essential part of the ongoing evaluation.14 Allowing for diverse approaches to this process will also be instructive.

Finally, the committee notes that it has placed some important issues outside the scope of this phase of the study. For example, it has not explored the matter of how to characterize security benefits. The committee recognizes that security threats to the energy system have multiplied in number and kind, but this and other issues have been deferred to Phase 2 of the project. The current committee is focusing on the basic problem of adapting the retrospective methodology to a prospective focus.

METHODOLOGY

Retrospective Analysis: Concepts

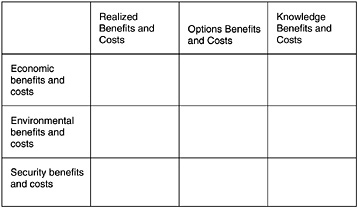

The methodology of the NRC’s 2001 retrospective study, Energy Research at DOE: Was It Worth It?, rests on two principal concepts. One is the benefits matrix, reproduced here as Figure 1. This matrix proved to be useful to decision makers in assessing R&D benefits for two reasons:

-

It focuses attention on the public good benefits—economic, environmental, and security—that are the objectives of DOE’s R&D program. These are captured in the rows of the matrix.

-

It distinguishes among the outcomes of the R&D pro-

FIGURE 1 Matrix for assessing benefits and costs retrospectively.

SOURCE: National Research Council. 2001. Energy Research at DOE: Was It Worth It? Washington D.C.: National Academy Press, p. 14.

-

grams, ranging from successful deployment in private markets to programs that produced useful knowledge but did not result in a successful technology. Benefits that had been realized or could be expected to be realized are included in the “Realized Benefits and Costs” column of the matrix. Benefits that might be realized if circumstances change in the future were included in the “Options” column. The “Knowledge” column recognized lessons learned from the study that will advance future understanding of related science and technology.

Each of the nine cells in the retrospective benefits matrix thus becomes an easily distinguished (and mutually exclusive) category of benefits. Even when it was impossible to quantify the benefit, as was often the case, a qualitative description of the benefits associated with a given cell still provided considerable useful information.

The other key concept in the retrospective study is the “cookbook,” which contains detailed instructions for calculating the benefits in each cell of the matrix.15 These instructions were written for analysts, but their existence proved to be of value to decision makers as well. The cookbook provides a consistent set of assumptions, concepts, and rules for all analysts to use. This consistency, in turn, allows decision makers to confidently compare the benefits reported for different technologies.

Prospective Analysis

The current study has a conceptual structure similar to that described above—a benefits framework adapted to the needs of prospective benefits estimation and a more technical, but still consistent, methodology for creating the information required by the matrix.

Compared with retrospective analysis, prospective evaluation is complicated by uncertainty about how the future will unfold. In the committee’s view, the chief uncertainties are these:

-

Uncertainty about the technological outcome of a program. Research is by nature an uncertain process, and any evaluation of R&D programs must consider the likelihood that the programs’ goals will be met. If a program’s goals are not fully met on time and on budget, the program may still produce important technological advances that have considerable benefits and should be reflected in the evaluation.

-

Uncertainty about the market acceptance of a technology. It is possible for a research program to meet all of its own goals and yet produce a technology that has no benefit because R&D on another technology has met the same need sooner, better, or cheaper. For example, DOE’s research program in advanced solid-state lighting may achieve its technical goals only to find that fluorescent lights have improved and dominate the lighting market. Similarly, flexi-fueled hybrid-electric automotive technology and cellulosic ethanol production may (both) improve enough to reduce the anticipated benefits of hydrogen-powered vehicles. Of course, the success of these competing technologies is itself uncertain.

-

Uncertainty about future states of the world. The benefit of a new technology will often depend on developments quite unrelated to the technology itself. For example, the benefit of energy-efficient lights will depend on the cost of electricity, which in turn depends on the costs of fuels such as natural gas and coal used to generate this electricity. And the benefits of carbon sequestration will only exist in a world in which carbon emissions from electric power plants are constrained.

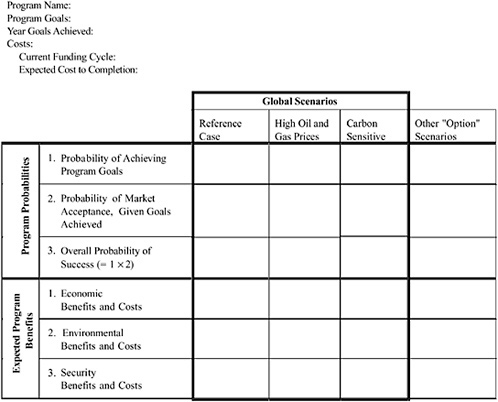

The benefits framework that the committee has developed for prospective evaluation builds on the methodology used in the NRC’s retrospective study. The prospective matrix is shown in Figure 2. The bottom three rows represent the same kinds of benefits—economic, environmental, and security—considered in the retrospective analysis. These rows of program benefits are supplemented with the three rows at the top of the matrix for quantitative probabilities, which describe the likelihood that the program will achieve its technical and market goals.

The columns of the matrix represent possible future states of the world, which are specified by DOE. The first of these is a reference case—for example, the Energy Information Administration’s Reference Case, described in the Annual Energy Outlook.16 The next two columns describe alternative scenarios that represent other possible futures and high-

FIGURE 2 Matrix for assessing benefits and costs prospectively.

light different policy issues. The column labeled “High Oil and Gas Prices” represents a scenario in which future oil and gas prices are significantly higher than those in the Reference Case. In the “Carbon Sensitive” scenario, concerns about greenhouse gas emissions have led to caps or tariffs on carbon emissions. The fourth column in Figure 2 covers the possibility that a program is intended to respond to (i.e., deliver net benefits in) a state of the world other than those captured by the first three columns. Note that while the probability of a scenario’s occurrence may significantly affect the estimated benefits of a program, the committee believes that the probability is determined by DOE policy. (Further description of the matrix elements is included in Appendix B of this letter report.)

As seen in Figure 1, the retrospective study employed a matrix with three columns: realized benefits, options benefits, and knowledge benefits. In the prospective case, programs do not yet have realized benefits, so the “realized benefits” category is not necessary. Although program components are expected to yield generic knowledge as well as particular technologies, the knowledge category is not appropriate as a primary goal of an applied energy program (as opposed to a basic energy science program); hence that category is not applicable. Similarly, in the retrospective study, many of the benefits categorized as “knowledge benefits” represented generic scientific advances that had not yet provided tangible benefits. Looking forward, the committee expects the projects to provide scientific knowledge on the way to future economic, environmental, or security benefits. The aim of the committee is to capture these future benefits in the prospective methodology and not to report knowledge benefits separately. Thus, columns identified in this prospective study instead expand the “options benefits” category employed earlier, as the programs are intended to yield benefits that vary with the future state of the world—indeed, sometimes different possible future scenarios drive different programs.

The proposed benefits methodology for the prospective evaluations is under development at the time of writing of this letter report. While the committee cannot in this report describe the methodology in more detail, it may be useful to review three important criteria that are guiding these efforts:

-

Simplicity but flexibility. While DOE’s applied R&D programs may be complex, the evaluation methodology must be relatively simple to apply if it is to be used widely. Expert technical and/or policy judgment is needed to know which simplifications are appropriate and when greater complexity (more potential outcomes or policy scenarios, for example) is needed to adequately characterize a program. The framework must be able to successfully accommodate and summarize analyses of varying degrees of complexity.

-

Transparency. Although the projects being evaluated are complex, in order for the results to be understood and used, decision makers must be able to understand the critical assumptions underlying the analysis, including the assumptions about the likelihood of various levels of success and the benefits in each scenario.

-

Consistency. Although each project has its own technical goals and potentially different markets, the committee requires that the same summarizing matrix be used for each project. The expected economic, environmental, and security benefits in the matrix must be defined in the same way, and each program must be considered under the same three scenarios. Using a consistent set of definitions and assumptions makes it easier to study a portfolio of programs,17 as the investment in learning the terminology associated with the evaluation of one program pays dividends when studying subsequent programs. It also facilitates comparisons between and aggregation across programs, as the expected benefits of different programs can be compared and totaled.

CONTENTS OF THE PHASE 1 FINAL REPORT

The committee expects to release its Phase 1 final report on methodology for estimating R&D benefits in February 2005. (In Phase 2, the committee will apply the methodology developed to a larger set of DOE programs and resolve any remaining methodological issues.) The Phase 1 final report will contain the following:

-

A description of the prospective benefits matrix, which the committee expects will be similar to the outline provided in this letter report;

-

Detailed guidance on the methodology for completing the matrix;

-

An outline of the process for applying the methodology, including the use of expert panels;

-

A summary of the reports prepared by the expert panels for the three test programs—advanced solid state lighting, carbon sequestration, and fuel cells—that were selected for evaluation; and

-

Recommendations for key issues to be resolved in the Phase 2 study, as well as suggestions to DOE on ways to improve its prospective benefits evaluations.

In its work to date, the committee has benefited greatly from the input and support of the DOE staff. It looks forward to their continued assistance in its future endeavors.

Robert W. Fri,

Chair

APPENDIX A COMMITTEE ON PROSPECTIVE BENEFITS OF DOE’S ENERGY EFFICIENCY AND FOSSIL ENERGY R&D PROGRAM

Robert W. Fri (Chair)

Senior Fellow Emeritus

Resources for the Future

Linda Cohen

Professor, Department of Economics

University of California, Irvine

James Corman

President

Energy Alternatives Studies, Inc.

Paul A. DeCotis

Director of Energy Analysis

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA)

Wesley Harris, NAE18

Head, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Martha A. Krebs

Consultant (Science Strategies)

George W. Norton

Professor, Agricultural and Applied Economics

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Rosalie Ruegg

President

Technology Impact Assessment (TIA) Consulting, Inc.

Maxine L. Savitz, NAE

General Manager, Honeywell, Inc. (retired)

Jack Siegel

President, Technology and Markets Group

Energy Resources International, Inc.

James E. Smith

Professor, Fuqua School of Business

Duke University

Terry Surles

Vice President

Electricity Innovation Institute

James L. Sweeney

Professor of Management Science and Engineering

Stanford University

John J. Wise, NAE

Vice President (retired)

Mobil Research and Development Corporation

APPENDIX B PROSPECTIVE MATRIX DETAILS

Overview

The committee’s proposed methodology for the prospective evaluation of DOE research and development programs disaggregates the expected benefits of a program into different components: probable benefits for different states of the world (the scenarios); different types of benefits; and different types of risks (see the subsection below on “Program Risks”). The disaggregation serves several purposes. First, the committee hopes that it aids in assessing the program components by providing a reasonably detailed list of the factors that enter an overall cost-benefit analysis. Second, some of the components (e.g., economic benefits) are easier to measure than others (security benefits). The disaggregation allows precise measures where warranted and avoids oversimplifications in other cases. Similarly, greater consensus exists about the magnitudes of some risks (e.g., for program technical success) than others (potential states of the world). The committee hopes to clarify debate over the value of programs by allowing common estimates, where appropriate, and isolating the less easily measured or more controversial components of the calculations. Finally, since the disaggregated approach clarifies whether a program is particularly risky or a relatively sure thing, it aids in assessing whether the DOE’s overall portfolio has a mix that is appropriate for a public applied R&D energy program.

Program Goals

The program goal and time of completion of a DOE program being evaluated prospectively should be defined so that after the time of completion, one can unambiguously determine whether the goal has been achieved. The unambiguous definition of the goal and time of completion is critical in the project evaluation.

Program Risks

Risks associated with the programs fall into two broad categories: Probability of Achieving Program Goals and Probability of Market Acceptance. The first category is the probability of meeting the specified goals with the resources expected to be employed during the life of the program. These resources include but are not limited to the technical, managerial, and financial support devoted to the project.

The Probability of Market Acceptance category addresses the likelihood that the technical accomplishments of a program will be used commercially. For this evaluation, it is assumed that the program technical goal is met sufficiently to allow the technology to move into commercial use. Factors to consider as possibly affecting success in market acceptance might include but are not limited to the following:

-

Competition. Is there work by others on either the same technology or different technologies that might meet the same need? Might these alternative solutions be available sooner or be cheaper? These questions would apply to work by others in the United States and in other parts of the world. Is this an area of intense competitive activity or is it primarily left to the government?

-

Window of opportunity. Will there still be a need for the technology when the program is expected to be completed? Are there social, environmental, or other factors that might eliminate or reduce the need for this technology? For example, as a result of unexpected, more stringent environmental regulations on diesel emissions, fuel and engine research programs designed to meet anticipated, more modest objectives were made obsolete.

-

Ease of implementation. Is implementation of this technology easy, or does it require changing other systems? For example, it would be easy to substitute a new catalyst into an existing reactor. On the other hand, a hydrogen-powered automobile would require a new fuel distribution system, making implementation more difficult (the “chicken and the egg” problem). As another example of an impediment to implementation, does this technology require workforce retraining?

-

Potential hazards. Are there any potential hazards or public safety concerns that might limit the use of this technology? For example, are there any potential by-products that might turn out to be an environmental or biological hazard incurring unexpected treatment costs or liability exposure?

-

Complementary technology requirement. Does the implementation of the technology require successful outcomes in other research and development programs?

-

Capital intensity. Does this technology require massive capital investment? Programs that result in highly capital intensive outcomes are less likely to be implemented even if the benefits are positive.

Market Scenarios

Three scenarios appear to incorporate futures that are relevant to a wide range of energy programs: a reference case, a world with substantially higher oil and/or gas prices, and a world in which carbon emissions are deemed a significant environmental hazard in need of regulatory response.

These scenarios are meant to refer to actual states of the world and not different policy regimes. That is, under the “Carbon Sensitive” scenario carbon emissions are determined to be a hazard, the “High Oil and Gas Price” scenario is due to actual supply or demand conditions, and so on. However, the functional use of the scenarios requires some assumptions about the policy responses.

The usefulness of the analysis is enhanced when the categories are standard across programs. Some programs, however, may be intended to respond to other states of the world.

The final “other ‘option’ scenario” column in the prospective benefits matrix (see Figure 2 in the body of this letter report) covers this possibility. It can be used to describe the scenario that justifies a program. This column need not be filled in if the program is intended to address one of the standard scenarios. If it is employed, the characteristics of the scenario should be described in full in a matrix appendix.

Program Benefits

The benefit categories included in the NRC’s retrospective study19 are appropriate for this analysis as well. Briefly, the benefits as defined in the retrospective report are as follows:

-

Economic net benefits are based on changes in the total market value of goods and services that can be produced in the U.S. economy under normal conditions…. The total market value can be increased as a result of technologies because a technology may reduce the cost of producing a given output or allow additional valuable outputs to be produced by the economy. This estimation must be computed on the basis of comparison with the next-best alternative, not some standard or average value.

-

Environmental net benefits are based on changes in the quality of the environment that will (or may) occur as a result of the technology. These changes are possible because the technology may allow regulations to change, or it may improve the environment under the existing regulations.

-

Security net benefits are based on changes in the probability or severity of abnormal, energy-related events that would adversely impact the overall economy or the environment.