2

From Retrospective to Prospective Evaluation

INTRODUCTION

The committee’s task was to recommend a proposed methodology that adapts the conceptual framework for the retrospective study (NRC, 2001) to the task of estimating prospective benefits. In performing this task, the committee sought to

-

Preserve the essential features of the retrospective methodology that had proved to be of value to decision makers;

-

Incorporate technical and market uncertainties associated with prospective analysis; and

-

Design a methodology that balances analytic rigor and ease of application.

ESSENTIAL FEATURES OF RETROSPECTIVE METHODOLOGY

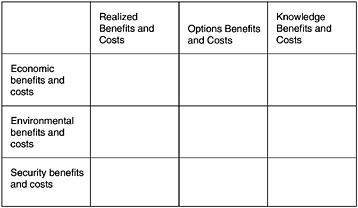

The methodology of the retrospective study rested on two principal concepts. One was the benefits matrix, reproduced below as Figure 2-1. This matrix proved to be useful to deci

FIGURE 2-1 Matrix for assessing benefits and costs retrospectively.

sion makers for assessing R&D benefits because it accomplished three things:

-

Focused attention on the public good benefits—economic, environmental, and security—that are the objective of DOE’s applied energy R&D programs. These were captured in the rows of the matrix.

-

Identified various outcomes of the R&D programs, ranging from successful deployment of a technology in private markets to the generation of knowledge that was useful but did not result in a successful technology. Benefits that had been realized or were expected to be realized were included in the “realized benefits and costs” column. Benefits that might be realized if circumstances change in the future were included in the “options benefits and costs” column. The “knowledge” column recognized the benefit of lessons learned from an R&D program or project that would advance our understanding of related science and technology.

-

Allowed programs to be compared in a way that is easily understood. The matrix does a good job of summarizing the complexities of programs and gives decision makers the ability to compare, although in a limited way, DOE programs according to their expected principal outcomes.

Each of the nine cells in the benefits matrix thus became an easily distinguished (and mutually exclusive) category of benefits. Even when it was impossible to quantify the benefit, as was often the case, a qualitative description of the benefits associated with a given cell still provided considerable useful information.

The other key concept in the retrospective study was the “cookbook,” which contained detailed instructions for how to calculate the benefits in each cell of the matrix.1 These instructions were written for analysts, but their existence

|

1 |

The cookbook is Appendix D of NRC (2001). |

proved to be of value to decision makers as well. The cookbook provided a consistent set of assumptions, concepts, and rules that all analysts should use. This consistency, in turn, allowed decision makers to confidently compare the benefits reported for different technologies.

UNCERTAINTIES OF PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS

The committee’s proposed methodology for the prospective evaluation of benefits builds on the above features to provide an analytical framework adapted to the needs of prospective analysis. It is a more technical, but still consistent, methodology for creating the information required by the matrix. In contrast to retrospective evaluation, however, prospective evaluation is complicated by uncertainty about how the future will unfold. In the committee’s view, the chief uncertainties are these:

-

Uncertainty about the technological outcome of a program. Research is inherently an uncertain process, and any evaluation of a research program must consider the likelihood that the program’s goals will be met. Even if a program’s goals are not fully met on time and on budget, the program may still produce important technological advances that have considerable benefits that should be reflected in the evaluation.

-

Uncertainty about the market acceptance of a technology. It is possible for a research program to meet all of its own technical goals yet produce a technology that is not accepted in the marketplace and therefore has no economic benefit because another technology has met the same need sooner, better, or more cheaply. For example, DOE’s research program in solid state lighting may achieve its technical goals only to find that fluorescent lights have improved and dominate the lighting market. Similarly, flex-fueled hybrid-electric automotive technology and cellulosic ethanol production may both improve enough to reduce the anticipated benefits of hydrogen-fueled vehicles. Of course, the success of these competing technologies is itself uncertain.2

-

Uncertainty about future states of the world. The benefit of a new technology will often depend on developments quite unrelated to the technology itself. For example, the benefit of energy-efficient lights will depend on the cost of electricity, which in turn depends on the cost of fuels like natural gas and coal used to generate the electricity. Similarly, the benefits of carbon sequestration will be greatest if carbon emissions are regulated, giving electricity producers incentives to deploy this technology.

-

Uncertainty about the attribution of program benefits to DOE’s R&D investments. In some instances, a DOE R&D program investment might be the sole reason for a technological breakthrough envisioned by the program. In other

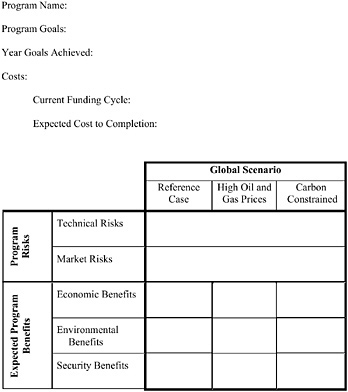

FIGURE 2-2 Results matrix for evaluating benefits and costs prospectively. The matrix shown in the figure differs from the preliminary matrix provided to the panels in June 2004.

-

instances, a private sector or foreign government investment might be the primary determining factor for technological success. It is difficult to know this with any certainty prospectively.

These four categories of uncertainties will apply to all programs, but the relative impact of a particular category will vary from program to program. A standard way to take uncertainties into account in cost-benefit analysis is to consider the “expected benefit,” which is the probability-weighted average of the benefits associated with all the possible outcomes of a program.

The benefits framework that the committee proposed for prospective evaluation incorporates these characteristics of the possible outcomes and attendant investment risk. This framework is summarized in matrix form in Figure 2-2. The bottom three rows represent the same three kinds of benefits—economic, environmental, or security benefits—considered in the retrospective analysis.3

The columns of the matrix represent possible future states of the world. The first of these is a reference case—here, the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA’s) Reference

Case, described in the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook. The second and third columns describe alternative scenarios reflecting different policy issues. The High Oil and Gas Prices scenario is a scenario in which future oil and gas prices are significantly higher than in the Reference Case. The Carbon Constrained scenario is one in which concerns about greenhouse gas emissions have led to caps or tariffs on carbon emissions. These scenarios are described in more detail in Chapter 3. Review panels are also invited to consider scenarios in addition to these three that might better elucidate the possible outcomes and benefits of individual programs.

It is important to note that the columns used in the retrospective study are not appropriate for prospective evaluation. The retrospective study employed a matrix with three columns: realized benefits, options benefits, and knowledge benefits. In the prospective case, programs have not yet realized benefits, so that category is not applicable or necessary. Similarly, in the retrospective study, many of the benefits categorized as “knowledge benefits” represented generic scientific advances that had not yet provided tangible benefits. Looking prospectively, the committee expects the projects to provide scientific knowledge on the way to future economic, environmental, or security benefits. However, the purpose of applied technology programs is to produce a technology with specific performance characteristics at a particular time. Thus, the development of knowledge is not the expected end result of an applied energy program (as opposed to a basic energy science program), so a knowledge column is not appropriate for prospective evaluation of applied programs. Finally, the “options” column in the retrospective matrix has, in effect, been transformed into three specific future states of the world for use in prospective evaluation.

KEY FINDINGS FROM EXAMPLE STUDIES

The committee organized three expert panels and assigned them the task of estimating prospective benefits for a particular DOE program. The panels were given some general advice on the process by which it was proposed they would arrive at their estimates (e.g., a matrix similar to that of Figure 2.2), but the full evaluation process was to be developed after learning from these initial experiences.4 In estimating prospective benefits, the panels identified a number of issues that need to be resolved in order to develop a uniform, practical methodology. This panel experience provided an essential foundation for the development of the committee’s methodology. Although the panels addressed diverse programs requiring different areas of expertise, the committee believes that the most important of their recommendations center on six problems:

-

Calculating benefits. In most cases, the panels relied on the National Energy Modeling System (NEMS) to compute benefits. While NEMS is the only available model with the detail and rigor required for such analysis, it has several deficiencies that might be addressed through refinements. First is the lack of transparency—the difficulty of identifying the critical assumptions on which the NEMS calculation is based. Second, it appears that NEMS does not calculate benefits using the rules established in Appendix D of the retrospective report (NRC, 2001) and that also apply for prospective calculations.5 Finally, running NEMS is both cumbersome and very resource-intensive, which greatly limits its utility for exploring alternative scenarios and technological outcomes. All three panels encountered these difficulties, thus raising the need for a more useful and simpler procedure for calculating benefits.

-

Isolating critical outcomes. The value of DOE funding depends on the technological risks involved, advances in competing technology that could deliver the same or similar benefits as the DOE program, and the extent to which non-DOE resources are being applied to advance the technology (e.g., by the private sector or foreign governments). All of the panels found it necessary to sort through a complex array of possible combinations of these factors and corresponding outcomes to isolate the few that could have a significant impact on the benefits of the DOE program in question. It is essential to evaluate these key alternative outcomes in addition to evaluating the benefits associated with complete success of the nominal DOE program.

-

Assessing probabilities. The prospective methodology requires assessment of the probability of technical and market success. The panels used different approaches for making these risk estimates. This experience shows that guidelines for risk assessment are essential to achieving a reasonable degree of uniformity among the program assessments.

-

Obtaining program information. Each of the panels encountered some degree of difficulty in obtaining basic information on the program being evaluated. In some cases, the information was available but hard to acquire under the time pressures at which the panels operated. In other cases, the information was not available or access to it was denied because of confidentiality concerns.

-

Managing the panels. While the charges to the three panels were the same—that is, they were all to complete the matrix—the committee imposed relatively little structure on the operation of the panels. While intentional, this decision had flaws and pointed to a number of steps that should be taken to ensure the best use of the experts’ time. Two issues were particularly important in the committee’s view. One is that the absence of planning before the first panel meeting

|

4 |

The methodological guidance given to the panels for this purpose is summarized in Appendix E. How the panels actually accomplished their task is summarized in Chapter 5. |

|

5 |

Chapter 3 discusses the technical problems with the NEMS calculation of benefits. |

-

created unnecessary confusion. The other is that the panels were recruited for their technical and market expertise, which did not necessarily include the expertise in decision analysis and benefits estimation that is required to produce a panel report.

-

Presenting the results. The panels uniformly observed that the matrix does not present the whole story of their evaluation. At best, it leaves out nuances important to understanding the significance of the benefit calculation. At worst, the matrix without further explanation could mislead decision makers. The concluding chapter, “Conclusions and Recommendations,” explains briefly how the recommended methodology and process presented in Chapters 3 and 4 deal with these problems.