Changing Approaches in Art Conservation: 1925 to the Present

Joyce Hill Stoner

Professor, Winterthur/University of Delaware

Program in Art Conservation

Winterthur Museum

Winterthur, Delaware

ABSTRACT

The years between 1925 and 1975 in the United States marked a period of pioneering progress and expansion in the field of art conservation: museums established conservation departments and analytical laboratories; the first art technical journals were published; and professional societies and training programs were established. From 1975 to the present, processes were refined, choices multiplied, and procedures that had once seemed black and white became gray and variable. There was also a hands-off or minimalist movement, increased attention to preventive conservation, and a new role for the conservator as a high-level collaborator.

The twenty-first-century conservator should work with museum scientists to understand the strengths and limitations of a vast array of possibilities for instrumental analysis, should collaborate with curators, archivists, archaeologists, architects, and artists, and should understand a vocabulary of technology and connoisseurship that may range from the contents of a shipwreck to Indian miniature paintings. Today’s conservator should understand integrated pest management, light levels, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems, and should be able to speak articulately about the field to audiences ranging from grade school groups to museum and university trustees. Rules are flexing with regard to use and handling of Native American materials in museums, removal of ceremonial substances, and collaboration with living artists. Conservators, who were once lonely advocates for the physical materials of art works and their long-term survival,

now must look at preservation in a much larger arena, including the cultures of origin and economic survival in the twenty-first century.

EVOLUTION OF THE FIELD OF CONSERVATION FROM 1925 TO 1975

The nineteenth century witnessed a growing collaboration between the fields of art and science. Michael Faraday made analytical and deterioration studies for the National Gallery in London, motivated by an official inquiry into the methods of cleaning paintings. He demonstrated the damaging effect on works of art of sulphur compounds liberated by coal smoke and gas lighting and showed that deterioration increased during London fogs and high humidity. Louis Pasteur carried out analytical studies of paint in the 1870s. A scientific department was established at the Staatliche Museen in Berlin in 1888, and the British Museum followed suit in 1921.

The years between 1925 and 1975 in the United States marked a period of pioneering progress and expansion in the field of art conservation. A special climate of cooperation among scientists, art historians, and restorers developed at the Fogg Art Museum in the late 1920s. One pivotal figure was Edward Waldo Forbes, the director of the Fogg from 1909 to 1944. He realized how misleading the contemporary practice of wholesale retouching of paintings could be. He encouraged technical investigation and X radiography. He was the chairman of the Advisory Committee for the first technical journal, Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts, published by the Fogg from 1932 to 1942. Forbes had approached Francis P. Garvin, the president of the Chemical Foundation, for a donation to finance the publication of Technical Studies.

Two significant “Fogg founding fathers” of art conservation were Rutherford John Gettens, the first chemist in the United States to be permanently employed by an art museum, and George L. Stout, the founder and first editor of Technical Studies. Gettens and Stout coauthored Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopaedia, first published in 1942 and reprinted in 1966. This useful compendium is still cited regularly, up to and including our most recent University of Delaware Ph.D. dissertation of 2002 on paint analysis in historic buildings by Susan Buck. Only a few dates and descriptions in the little Gettens and Stout book are now outdated.

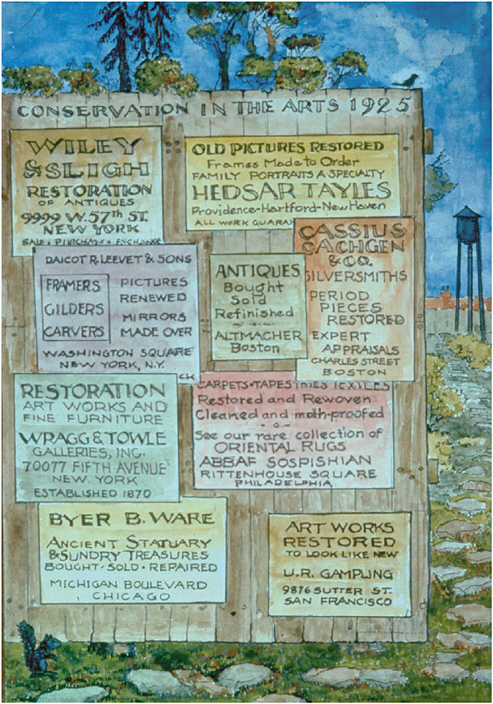

In 1974 Gettens presented a paper suggesting that we begin a conservation history initiative, and Stout helped launch (after Gettens’s sudden death) our Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (FAIC) oral history project. We now have more than 150 transcribed interviews with pioneer conservation professionals. Stout lectured about the history of the field from 1925 to 1975 at our American Institute for Conservation meeting in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1976, illustrating his remarks with his own watercolors presenting the evolving profession (see Figure 1).

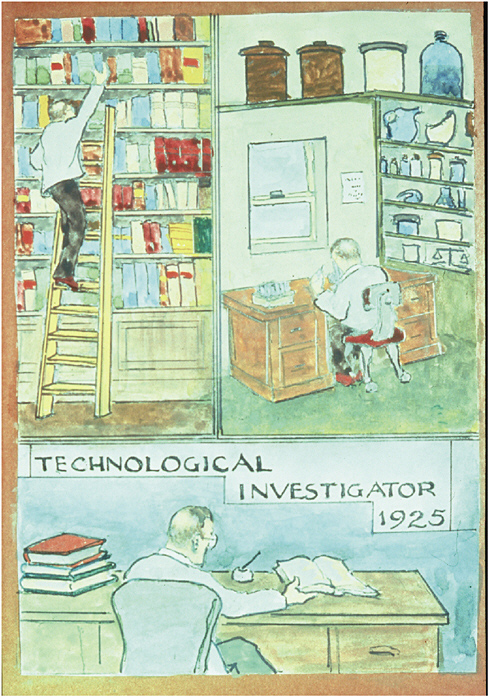

Stout noted that before the Fogg launched its technical laboratory in 1928 featuring the collaboration of art historians, scientists, and practicing conserva-

tors that he dubbed “the three-legged stool,” there had been lone “technological investigators” in some museums (see Figure 2). Alan Burroughs (1897-1965) of the Fogg traveled to major museums in Europe with an old Picker X-ray machine in 1926, making landmark X radiographs of Old Master paintings. Burroughs published his findings in 1938 as Art Criticism from a Laboratory. X radiographs represented the paragon of technical investigation for paintings and sculpture for the first half of the twentieth century, accompanied by examination with ultraviolet light. X rays had been discovered in 1895 by Roentgen, and paintings were first x-rayed within a year. Christian Wolters, one of the pioneer conservators of Germany, wrote his dissertation on the importance of radiography for art history in 1936. One issue of the Philadelphia Museum Bulletin of 1940 featured a solemn, worshipful photograph of an X-ray unit as its cover image. By 1931 James Joseph Rorimer (1905-1966) of the Metropolitan Museum of Art had published Ultraviolet Rays and Their Use in the Examination of Works of Art.

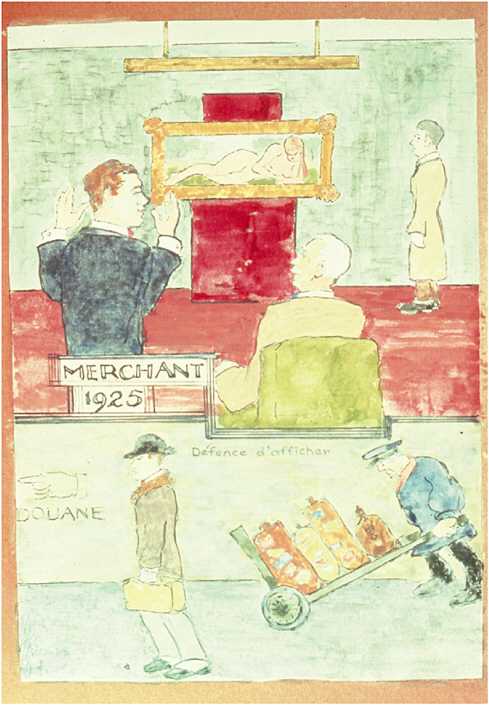

Stout described the 1920s as

the great days of Berenson. There was contempt for concern about condition. That was as naughty as to inquire about the digestive system of an opera singer. You didn’t look into those things—it wasn’t proper. And that was very good for the trade. When a dealer sold a picture, he didn’t like to have anyone consider for a moment that the condition of that picture had anything to do with the case. This was something of beauty and your sensitivities for the quality of the beauty were the important matter. Whether it was about to buckle up and begin to give you hell in another couple of years was something never to be considered (see Figure 3).1

There was no luxury of specialization during the early days of the three-legged-stool collaboration at the Fogg. Everyone worked on everything; the conservators and scientists brainstormed, took notes, documented, collected pigments, and painted out samples of paints on the walls. No one was full time; they even did hit-and-run paint chip analysis for the Harvard police. Forbes and later Stout taught young art historians about historical artists’ techniques, insisting that they paint in egg tempera and fresco themselves; these students went off to become curators and directors in museums throughout the United States, bringing with them a unique concern for connoisseurship and the physical presence of works of art.

In the early 1950s members of the original Fogg team of conservators and conservation scientists were dispersed, largely because of funding issues and the attitude of the administration at that time, according to Richard Buck.2 Gettens next founded the technical laboratory at the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., in a humble space once used for packing crates, and Richard Buck helped to design the first Regional Conservation Laboratory, the Intermuseum Conservation Association (ICA) at the Allen Art Museum in Oberlin, Ohio, which opened in 1953. The ICA was founded by six major Midwest museums to provide professional and cost-effective art con-

servation services. There are now 12 regional centers, and in 1997 this group began a consortium known as RAP (Regional Alliance for Preservation) with a website (http://www.rap-arcc.org).

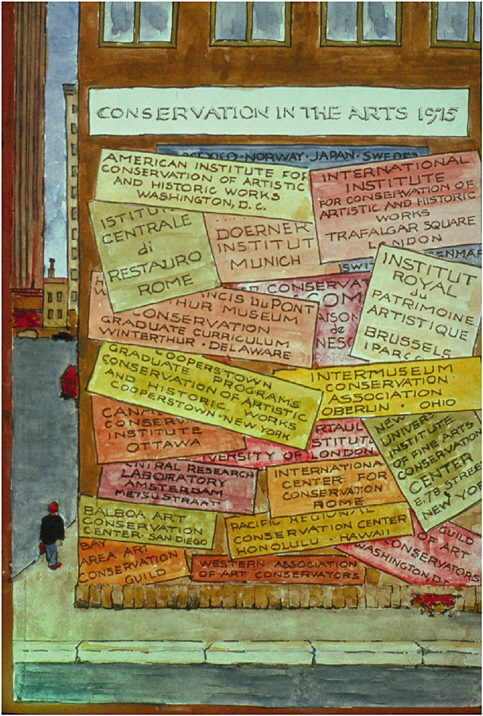

Major professional societies and training programs also appeared between 1925 and 1975. The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC) was incorporated under British law in 1950 as “a permanent organization to co-ordinate and improve the knowledge, methods, and working standards needed to protect and preserve precious materials of all kinds.” Since 1967 when the first meeting on climate control was held in London (see Figure 4), triennial or biennial congresses have been held in international locations on special topics ranging from archaeological conservation (in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1975, with attention to the recovery of the warship Wasa) to library and archive conservation (Baltimore, Maryland, in 2002, with accompanying visits to the paper conservation department of the Library of Congress). Harold Plenderleith (1898-1997), founding member and author of what was once considered the conservation “Bible,” The Conservation of Antiquities and Works of Art: Treatment, Repair, and Restoration (1956) noted, “We never envisaged more than 50

FIGURE 4 The first triennial meeting of the International Institute for Conservation, in front of Albert Hall, London, 1967.

fellows because there weren’t 50 fellows in existence who shared our ideas or were adequately experienced in scientific conservation.” As of June 2002 there were almost 2,400 individual members of this international body, including 301 fellows. (This figure does not fairly represent the international population of conservators, as many now elect to join only their regional groups because of economic concerns and ready availability of key professional information on the World Wide Web; more information about IIC can be found at http://www.iiconservation.org/.)

IIC began publication of its quarterly journal Studies in Conservation in 1952 and sponsored an international abstracting periodical IIC Abstracts in 1955. Technical Studies published by the Fogg from 1932-1942 had also contained abstracts of the international literature, and Gettens compiled Abstracts of Technical Studies in Art and Archaeology (published by the Freer in 1955), a fairly slender volume covering literature published between 1943 and 1952. (Stout and other conservators had been active elsewhere during World War II as officers in the Arts and Monuments initiative to identify and protect cultural heritage.) IIC Abstracts moved to the New York University (NYU) Conservation Center in 1966, and the name of the publication was changed to Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts (AATA). AATA moved to the Getty Conservation Institute in 1985 (see Figure 5), and became available online in 2002 (http://aata.getty.edu/NPS). The conservation literature vastly expanded between 1975 and 1990. When this author was a

FIGURE 5 The Editorial Board of Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts, semiannual meeting in 1988, held at the Canadian Conservation Institute.

FIGURE 6 The first meeting of the International Institute for Conservation-American Group at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1960.

graduate conservation student at the NYU Conservation Center in the 1960s, very few books were available on the topic of art conservation. Current conservation graduate students can readily spend our new Gutmann Foundation grants of $3,000 on books in their specialties; I doubt I could have spent $300 in 1968.

The American Group of the IIC began in 1960 (see Figure 6) and became the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) in 1972, publishing a journal and a newsletter and establishing a 501(c)(3) foundation (FAIC). The AIC now has about 3,000 members, including 860 fellows or professional associates (http://aic.stanford.edu). The National Conservation Advisory Council (NCAC) was organized in 1973, funded by the National Museum Act of the Smithsonian Institution. The NCAC surveyed needs of the field and published useful and colorful booklets and became the National Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property (NIC) in 1982. Whereas individual conservators are members of the AIC, the NIC is composed of conservation associations that meet to discuss overarching issues, such as preservation of outdoor sculpture throughout the United States and historic houses and their contents. In 1997 the NIC changed its name to Heritage Preservation and now has 156 institutional members (http://www.heritagepreservation.org/).

Major conservation research laboratories were also founded during this period. William J. Young sponsored seminars in 1958, 1965, and 1970 on “The Application of Science in Examination of Works of Art” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the laboratory there had begun in 1930. In 1950 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. established a fellowship at the Mellon Institute in Pittsburgh. Robert Feller focused on natural and synthetic picture varnishes, color, and the damaging effects of light exposure. In 1976 the research project was reorganized as the Research Center on the Materials of the Artist and Conservator at Carnegie Mellon University. In 1988 Feller retired and Paul Whitmore came to the center to become the director. Whitmore edited an excellent compilation of Feller’s research, Contributions to Conservation Science, published in 2002. Originally established in 1963, principally to provide technical support to the Smithsonian museums in the analysis and conservation needs of the collections, the Conservation Analytical Laboratory (CAL) moved in 1983 to the Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland (see Figure 7). In January 1998 the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution voted to rename CAL the Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education (SCMRE). The Getty Trust and its various branches is our most significant recent addition; major activities were defined in 1982. In the summer of 1985 the Getty Conservation Institute took up

FIGURE 7 The Conservation Analytical Laboratory building of the Smithsonian Institution (now known as SCMRE, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education).

quarters in rented warehouse space at the Marina del Rey, and in 1997 joined other Getty branches at the Getty Center in California, an acropolis in travertine on the hills of Brentwood, representing the apotheosis of the architecture with dedicated space for conservation.

Conservation training evolved from apprenticeship to formal education and training programs in London in 1934, Vienna in 1936, Munich in 1938, Rome in 1943, and New York in 1960. The other two U.S. fine arts graduate programs opened in 1970 and 1974. As of 1994 there were at least 50 programs in 30 countries in the fine arts and another 50 in archaeological materials, books, decorative arts, and musical instruments according to a directory co-published by the Getty Conservation Institute. The Conservation Center at the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University accepted its first four graduate students in 1960; we students studied in the basements of the Duke mansion at One East 78th Street. In 1983 the program moved across the street to a converted brownstone with 11 floors of conservation laboratories, classrooms, and libraries; eight students are now accepted each year. Ten students were accepted annually into the Cooperstown Graduate Program in the conservation of historic and artistic works beginning in 1970. This program relocated to Buffalo State College in 1987. In 1974 a third graduate program was sponsored jointly by the University of Delaware and the Winterthur Museum. Both the University of Delaware and Buffalo State College have awarded space to their art conservation departments in the flagship buildings of their institutions, another encouraging sign of the architectural status now granted our profession. George Stout summarized the state of conservation in 1975 with another collage of a fence (see Figure 8). The Conservation Education Program at Columbia University accepted students in 1981 for training in library and archives conservation; this program moved to the University of Texas in 1992. The conservation training programs also have an association, ANAGPIC (Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation), including the Master of Art Conservation Program at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and the Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard. The students from the programs convene annually and present papers.3

CHANGING STYLES OF CONSERVATION: 1975 TO THE PRESENT

The Fogg conservators noted in their interviews that they rarely specialized; there are now nine specialty groups listed by material in each AIC Newsletter: architecture, book and paper, electronic media, objects, paintings, photographic materials, RATS (research and technical studies), textiles, and wooden artifacts. Another group represents the particular concerns of conservators in private practice. There is also an independent group, the Society of the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC). The International Council of Museums-Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) (http://www.icom-cc.org) has at least 18 working groups, including an active group on preventive conservation for conservators

who specialize in climate and pest control, changing exhibition, loans, and shipment. All these spin-off groups are publishing, conducting meetings and workshops, and collaborating with scientists or curators, architects, librarians, and artists.

Methods of analysis have become far more sophisticated than just X radiography or examination with ultraviolet light; the Sackler conference of 2003 at the National Academy of Sciences elaborated on many of these excellent resources. I will note that for my own specialty, a professional paper on paintings conservation is now rarely without cross-sections indicating the layered buildup of paint films, dirt, and varnishes shown in normal and in ultraviolet illumination, often with supporting Fourier transform infra red (FTIR) or x-ray diffraction (XRF) data. The landmark article launching this work was Joyce Plesters’s article for Studies in Conservation, “Cross-sections and Chemical Analysis of Paint Samples.” Ashok Roy of the National Gallery, London, noted in his Forbes lecture for the IIC that this 1956 paper is the single most cited reference in the whole of the literature of conservation.

By the middle 1970s a hands-off, minimalist, or “less is more” approach appeared, subsequent to our initial excitement regarding many new tools and techniques. For example, in paintings conservation the heat table was first introduced in 1948 in Germany and the United Kingdom, and vacuum pressure was added in 1955 (see Figure 9). About 20 years later, in 1974, a lining moratorium was suggested at a conference in Greenwich, England, reinforced at ICOM-CC

FIGURE 9 The use of a vacuum heat table, a typical treatment of the late 1960s and 1970s (Michael Heslip, paintings conservator at Winterthur Museum in the late 1970s).

meetings in Venice in 1975 and again at a special 1976 meeting in Ottawa. The problems caused by old and new lining technologies were reexamined. In 1992 I surveyed practicing paintings conservators in the United States; conservators who once said they had formerly lined nearly every painting they treated now reported lining only about 10 percent of their current treatments.4 Teaching treatments became more difficult, as there was now a complex menu of choices—loose linings, drop linings, edge linings, hand linings, humidity treatments, suction tables, local suction platforms, and more highly controlled vacuum tables—and lining is only one of many types of treatments used for paintings. We also have a complex menu of new adhesives and new electronic tools; we have “pharmacists of conservation” who specialize in supplying new spatulas, sampling kits, retouching supplies, and cleaning gel ingredients. There are many new approaches to removing varnishes—new enzymes, gels, and aqueous materials—less toxic and more specific in what they remove, thanks to changes made by conservation scientists or science-friendly conservators such as Richard Wolbers.5 My 1992 survey also revealed that many paintings conservators who used to remove varnishes entirely now may simply thin or reduce them instead, another more conservative approach.

A minimally interventive philosophy has now been adopted by most conservators, especially as we revisit our own treatments from 25 years ago and as we watch our materials along with ourselves and our attitudes age. Marjorie Cohn, formerly a conservator of prints and drawings and now a curator and director at the Fogg, noted in the 2001 history issue of the Journal of the Institute of Paper Conservation, “Think first of the high value, both aesthetic and commercial, now attached to the unvarnished or unlined canvas. But ‘unwashed’ is now also a sales point in the catalogue descriptions of old master prints.”6 Our Art Conservation Program faculty members all generally adhere to this minimally interventive philosophy. In furniture conservation new approaches aim to preserve every bit of original material.7

We are now more aware of health hazards for the conservator and for the good health of the environment. Marjorie Cohn continued in her paper with a succinct summary of some other changes:

One by one over the past three decades options for fumigation have been deemed too hazardous, until now there are no facilities remaining at my institution, Harvard University, and good housekeeping rather than extermination is the mode. Likewise, carcinogenic solvents have been minimized in the conservators’ repertory, and ventilation and disposal are now the first engineering priority in the design of facilities.8

More interdisciplinary research and publications have appeared in recent years. Cohn was asked by Agnes Mongan of the Fogg to write what she now notes was an “unprecedented essay” for an Ingres catalogue in 1967 and continued that since then more art historians have come to appreciate the potential of technical

examination and scientific analysis, and “conservators themselves have realized the essential importance of historical evidence on and in the works of art themselves.”9 George Stout’s three-legged-stool approach is embodied in an increasing number of publications authored by teams of conservators with art historians and scientists, such as Art and Autoradiography: Insights into the Genesis of Paintings by Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and Vermeer from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1982 and Examining Velasquez in 1988. There are now paired fellowships sponsored by the National Gallery and the Getty encouraging similar teams to create future publications. Textile conservators may now embrace a “connoisseurship bias” while choosing treatment options.10 Objects conservators may now elect to retain ritual substances such as yak butter that were applied to Tibetan sculptures. We have become more aware of respecting a nd retaining age value, historical value, and commemorative value, such as the proverbial blood on Lincoln’s shirt. Susan Heald, a textile conservator of the National Museum of the American Indian, gave a memorable talk for our graduate students. Heald worked with the Siletz regalia makers to stabilize pieces before the dance and get them ready for dancing during the dance house dedication ceremony. She noted, “For me this was a career altering experience to see these pieces danced on the night of the dance house dedication—it was very emotional for me and many others.” She described the smoky night atmosphere of the night of the dance she was allowed to observe (see Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 Susan Heald with members of the Siletz community at the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.

Other issues and concerns that would probably have never occurred to conservators in the 1950s and 1960s emerged following NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, which was discussed extensively by Miriam Clavir, senior anthropological conservator at the University of British Columbia, in her book Preserving What Is Valued: Museums, Conservation, and First Nations (UBC Press, 2002). People from First Nations may be reclaiming their sacred materials and reburying them; however, these materials may now have indelible museum registration numbers that must be removed from fragile surfaces or, even more important, be dangerously full of toxic pesticides that were state-of-the-art treatments in museums several decades ago.

Glenn Wharton, objects conservator who wrote his dissertation for the University College London on “Heritage Conservation as Social Intervention,” reported in the International Council of Museums–Committee for Conservation Preprints on the case of the royal Hawaiian monument Kamehameha the First. The state of Hawaii asked Wharton to remove the brightly colored paints that had been applied to the surface, returning the gilded bronze monument to its original state as part of the NIC’s Save Outdoor Sculpture. He soon learned that the local people intentionally paint Kamehameha in lifelike colors and hold annual celebrations with chants and parades. He convinced the state to support a community-based, two-and-one-half-year participatory conservation project that essentially gave the community a seat at the table in deciding how to conserve the monument. Wharton brought current theory from material culture studies, ethnography, and a reflexive stance to the study. He noted, “The recognition of cultural relativism and contested meanings embedded in material objects has begun to enter conservation literature.”11

In a landmark conservation conference in 1980 at the National Gallery of Canada, conservators, artists, scientists, and curators discussed issues relevant to the conservation of contemporary art. Several conservators spoke about their collaborations with living artists and the importance of interviewing artists to ascertain their views about materials and addressing damages to their pieces. Consulting and working with artists or collaborating with native Americans have been categorized together as acknowledging the cultures of origin, yet another important new direction for conservation.

CONSERVATION SCIENCE IN THE LAST DECADE

The number of conservation scientists and scientific research and analytical laboratories in the United States has increased substantially since the early 1990s. The inclusion of sophisticated scientific data in scholarly conservation conference papers and publications has become standard, enhanced by the students and graduates of active U.S. and U.K. doctoral programs. Conservation methods have been improved by jointly sponsored conservation science research, demonstrating such factors as the impact of solvents on paint films, the absorption of dirt by

acrylic paint, and the impact of temperature and humidity changes, with team members from the Getty Conservation Institute, the National Gallery of Art, the Canadian Conservation Institute, and the Tate in Britain.

Since the year 2000, Angelica Rudenstine and the Mellon Foundation have taken conservation science another quantum leap forward. In the mid-1990s Mrs. Rudenstine interviewed conservation leaders to determine areas of need within the profession. She identified both conservation of photographic materials and conservation science and has made carefully considered grants available for training, workshops, and internships in those areas. Mrs. Rudenstine embodies a unique case of highly directed and hands-on improvement by the leader of a granting organization. She has funded and thereby created new conservation science positions in graduate training programs and major museum conservation laboratories. She has also imaginatively provided underwriting for talented younger conservation professionals, such as Philip Klausmeyer, who has returned to graduate study in order to enhance the scientific capabilities and instrumentation at his home institution, the Worcester Art Museum.

The field of conservation science would not have been able to gainfully absorb the Mellon’s munificence in 1975. Mrs. Rudenstine scrupulously investigates the staff and capacity of an institution before making a grant. The integration of scientific understanding and conservation practice within well-trained individuals or by cooperating teams is a phenomenon of the last decade, and her programs have taken advantage of this moment in conservation history.

As I mentioned earlier, the multiplication of approaches, sophistication of scientific research, and explosion of information has not made it easy to be a professor of art conservation. There are no old and outdated methods that we can now delete from the curriculum because someone in the past may have used them on the work we must treat. We now believe that the conservators of the twenty-first century that we are now training must thoroughly know their specialties, including current philosophy, history, literature, ethics, and the material properties and methods of analysis (subjects might range from underwater cannonballs to ivory miniatures); collaborate with scientists and be able to understand scientific terms and methods; cooperate with allied professionals, including archaeologists, art historians, and the various cultures of origin; understand proper light levels, indoor pollutants, insect life cycles, climate control, emergency preparedness, and toxicity; be articulate advocates who write papers, give presentations, and in this time of economic cutbacks, be able to charm politicians, foundation heads, and reporters from “Sixty Minutes” if necessary. Perhaps we can now say that conservation has evolved from George Stout’s three-legged stool of the early days of the Fogg Art Museum to a twenty-first-century version of a ten-legged settee.

NOTES