Critical Integration and Coordination Issues in Urban Security

George Bugliarello

Polytechnic University

National Academy of Engineering

The effectiveness of an urban security system depends ultimately on the coordination and integration of all of its components—from sensors to intelligence, from first responders to hardening of potential targets—as well as on its coordination and integration with regional and national security systems.

Integration and coordination are complementary approaches to the goal of creating an organic system for counterterrorism. In integration, components of the system are fused into a single organization under a single command. In coordination, different independent components, such as entities in the public and private sectors, are connected by compacts and other agreements to operate in unison and share resources to thwart the possibility and consequences of terrorist attacks.

Integration and coordination constitute one of the most difficult challenges in urban security, indeed, in any security system, as they span social and technological aspects and their critical interfaces. Clearly, the concerns and measures involved in urban security are of concern also to government jurisdictions beyond cities, but the purpose of this paper is to focus specifically on some of the major critical issues in achieving such coordination and integration in a city. They include

-

unified command and control

-

integration of telecommunication systems to provide compatibility, availability, and redundancies

-

coordination of the resources of the private sector with those of the public sector (public-private coordination)

-

coordination of different administrative jurisdictions

-

local coordination of security approaches in specific areas of a city that encompass significant potential targets of terrorist attacks

-

urban security-university interfaces

-

public awareness, communication, and education

-

identification and protection of critical terrorist supplies

-

dual-purpose integration

UNIFIED COMMAND AND CONTROL

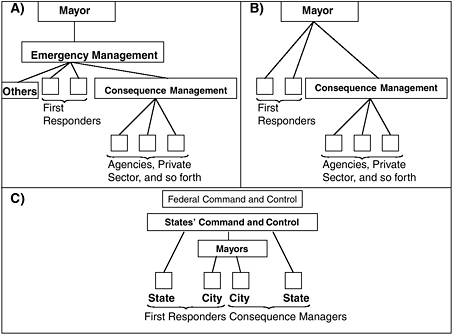

Organization of the systems involved in the array of urban security tasks, from prevention to emergency response to recovery, may vary from city to city and from country to country, but the imperative in every case is that in an emergency the command and control of those systems be coordinated and unified. A key question is where the decision making resides and how the staff of the top decision makers is organized to coordinate the responses (Figure 1). This has to do specifically with the architecture of the relation between the city’s top decision makers—typically the mayor—and the first responders and emergency managers. Figure 1 shows three examples of architecture from among the many possible. They are characterized by different schemes for relating the first responders

FIGURE 1 Three command and control architectures.

and the consequence managers (such as offices of emergency management [OEMs]) to the mayor and, in Architecture C, to higher levels of command and control authority. In Architecture A, the mayor is the ultimate authority, as is usually the case, but an emergency management control center relieves the mayor and his or her immediate staff of more detailed involvement in coordinating the inputs of the first responders and the consequence management activities. Architecture B characterizes the situation in New York City, where the first responders (police, fire departments, and emergency medical services) operate in parallel to the OEM, which is responsible for consequence management and coordinates a large number of agencies and private sector organizations. The first responders respond directly and report to the mayor in parallel with the OEM. This arrangement presents more operational complications than one where there is an overall coordinator of emergencies reporting directly to the mayor—a unified command center supporting the mayor’s decision making. However, in New York City, the connection between the mayor and the OEM is strengthened by a deputy mayor, and, if necessary, the mayor, being located in an emergency in the OEM. In Architecture C, which can complement other architectures such as those shown in A and B, higher jurisdictional levels (state, federal) can be involved in the command and control and coordination of lower levels—cities and even directly first responders and agencies within them.

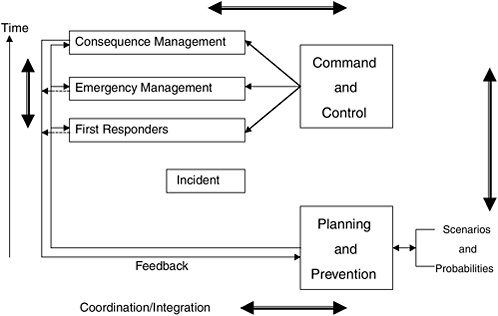

An effective command and control system requires integration and coordination along time sequences—from the intervention of the first responders after an incident, to the emergency management of immediate short-range consequences of the incident, to the management of long-term consequences. The integration also needs to encompass the planning and prevention activities that produce scenarios and related probabilities (Figure 2).

The importance of coordination in postincident activities was painfully evident during the blackout of August 14, 2003, which affected some 50 million people in the northeastern United States. All traffic light systems in New York City were incapacitated, and the policing of traffic at many intersections was left to individual citizens, who on their own attempted to untangle and regulate traffic.

One of the most difficult tasks in a large urban setting is evacuation. Large numbers of evacuees can overwhelm the logistics and health care resources of a city and require coordination with agencies in other areas. The situation after the recent earthquake and tsunami disaster in the Indian Ocean region has shown how enormous the task can be in a major incident. Multiple incidents, at brief temporal and spatial distance from each other, can further complicate evacuation, and so can the necessary counterflow of incident responders toward the incident site.

FIGURE 2 An incident’s coordination/integration.

TELECOMMUNICATIONS— COMPATIBILITY AND REDUNDANCIES

Telecommunications can be the most vulnerable aspect of urban security. They are essential to making integration and coordination possible. An example on September 11, 2001, in New York City was the inability to reach firefighters in the twin towers and the incompatible frequencies of the fire department and the police department.

Extraordinary volumes of cellular phone calls, which are typical of incidents, can lead to gridlock; hence the need, through coordination, to utilize a multiplicity of networks, including private business networks. Preferential access for priority communications and alternative channels of communication need to be provided, and critical components of the multiple communications system should not be placed in the same location, as they were on September 11, 2001. In the August 2003 electric power blackouts, agencies in New York City that relied on cellular phones could not reach members of their own staffs. The situation is now being addressed by the creation of a dedicated network for city agencies and other critical entities. Communications security also involves cybersecurity, the physical integrity of the network, and the ability to minimize terrorist denial of service actions, whether they are the ultimate goal of an attack or serve as a preliminary to other terrorist acts.

PUBLIC-PRIVATE COORDINATION

When a large part of the infrastructure is in private hands, as in the United States (for example, about 80 percent is private in New York City) there is a need to coordinate it with the public agencies involved in incidence response. Insurance companies are largely private and can have a significant role in the security of a city. For instance, they can provide incentives to encourage the private sector to strengthen the security of its buildings through the use of guards, cameras, and sensors as well as other measures, such as barriers and reinforced structures. Coordination with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in planning and consequence management is another important facet.

Public-private coordination is also important for incident management inside private organizations and for recovery operations. For instance, the clearing of debris from a major incident is often beyond the capacity of municipal services and requires utilization of private sector enterprises. After the World Trade Center attack, private engineering firms assisted the city in assessing damage and planning recovery, and private construction and earthmoving and carting companies were engaged to secure damaged sites and remove the large amount of debris created by the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings.

Insurance companies could be significant in recovery operations, too, as with fallout of radioactive material on the roofs of buildings and other surfaces. Depending on the nature of the materials that constitute these surfaces, the radioactive fallout might react with those materials, making it imperative to remove it as rapidly as possible before reactions take place that incorporate radioactivity in the surface material. Insurance companies could influence the safety and security of buildings by offering incentives in the selection of the material used in the roofs and in encouraging speedy removal.

COORDINATION OF DIFFERENT ADMINISTRATIVE JURISDICTIONS

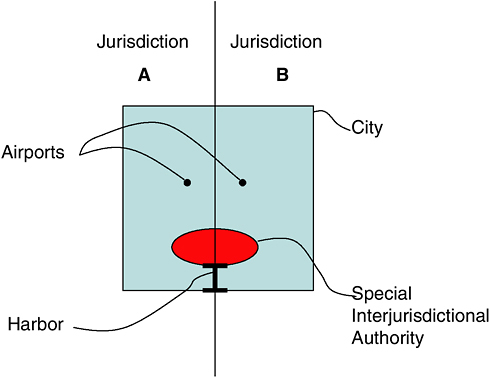

In many larger cities, the city center and the outlying areas—still part of the metropolitan complex—are under different jurisdictions, making coordination of their preparation and their responses quite complex (Figure 3). In the case of New York City, for example, Greater New York extends to New York State counties in Long Island and to the north of the city, each with its own incident prevention and response organization, as well as to counties in two other states, Connecticut and New Jersey. All these areas are bound to be profoundly affected by an attack on the city center, for example, in a potential evacuation. Similarly, in Washington, D.C., the District of Columbia borders on the states of Maryland and Virginia. In New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, the coordination of emergency responses is facilitated by a Federal Emergency Assistance Compact. In New York and New Jersey, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

FIGURE 3 Multiple jurisdictions, requiring multiple levels of coordination.

has jurisdiction over the harbors and airports of the metropolitan area, and responsibility for their security. (The waterways of the metropolitan area are patrolled also by the U.S. Coast Guard.) Thus special authorities like the Port Authority are an important coordination and integration mechanism. They might have their own security forces, their own land, their own buildings, and their own architectural and operational standards. This, however, can also have negative consequences, if some of their standards are different from those of the city, as with the stairways in the World Trade Center twin towers. Coordination of the complex of transportation, pedestrian movements, emergency responders, shelters, and logistic support becomes even more challenging in the evacuation of several areas, whether contiguous or in other portions of the city, and whether these events are simultaneous or sequential.

Apparently, thus far, no major city worldwide has an effective evacuation plan for the entire city, but at best has only plans for partial evacuation. Evacuation, among its many aspects, requires providing simultaneous access to first responders and coordination of traffic lights through the areas of concern and often through much of the city. In the United States a complex issue with a still not fully fathomed impact is the interaction and coordination of urban security

systems with the complex organization of the recently established U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Coordination and integration of different jurisdictions are necessary to protect the extended footprint of concern for a city’s protection. On September 11, 2001, that concern clearly would have extended beyond New York City and Washington, D.C., to airports, such as the airport in Boston, conveying passengers to these cities. In terms of ports, the footprint encompasses not only the ships entering harbors but also the inspection and certification at ports of origin, as well as the protection from blockages of waterways logistically critical to the city. Transshipment points, where goods are transferred from conveyance to conveyance, whether at sea or land, or in the transport of baggage from airline to airline, are other potential terrorist penetration points of concern to the security of cities. On trains, as in the Madrid attack, the footprint encompasses places outside the city itself, where terrorists might board or implant devices. Electrical and telecommunications networks, with their long geographic span, are also part of the footprint of concern.

LOCAL COORDINATION

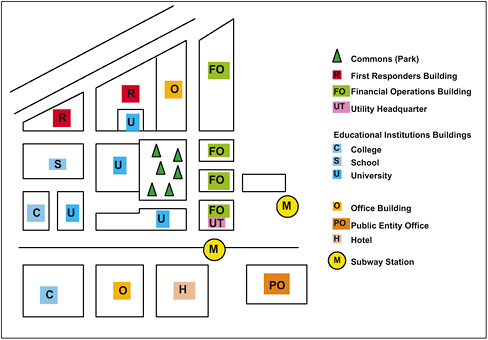

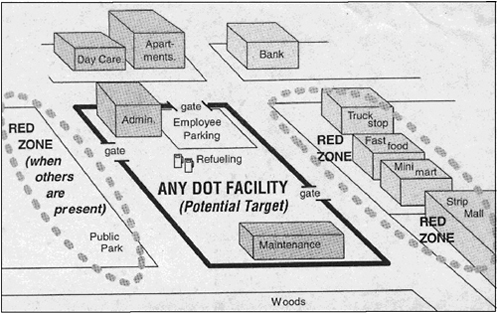

In every city there are special areas encompassing a multitude of uses and diverse institutions that are critical to security or are potentially rich targets. An example is Metrotech in New York City (Brooklyn; see Figure 4), with different

FIGURE 4 A site requiring local integration (Metrotech).

|

Box 1 Local Integration Components Preventive Measures Barriers architecture Sensor networks Telecom security Surveillance Incident Management Command and control systems Evacuation procedures Emergency medical resources Emergency shelters Rescue operations Emergency communication networks and ad hoc networks Debris removal services Utilities and other infrastructure emergency repair capabilities |

entities of different characteristics, both public and private, that need to be coordinated in the prevention of and response to a terrorist act. In a small area of fewer than 20 acres, Metrotech encompasses critical police and fire department facilities (the 911 emergency telephone hot line, and the headquarters of the city’s fire department and Department of Information Technology); business offices; institutes of higher education; a school; highly technological financial services facilities; a hotel; commercial establishments, such as restaurants and other shops; multiple subway lines and stations; and crowded road and pedestrian traffic. A major incident in such a dense and diverse area could force evacuation to street level of up to 30 thousand people. Each component of Metrotech has its own emergency plan, but for an incident affecting the entire area, such plans need to be coordinated with those of the other entities in the area, for example, to identify other security risks common to the area and to reduce the possibility that the large potential population brought out of the buildings and subways in the emergency might itself become the target of an attack. It is important to identify throughout a city similar local areas or districts that might require a coordinated plan and to determine the components of such a plan (see Box 1). Entertainment centers, utilities installations (for example, Figure 5) and transportation hubs (major stations and airports), with all the other activities they attract around them, are other examples of environments where local integration is critical for a more effective response. A focus on local coordination also facilitates surveillance, dual-purpose integration, and the identification of potential terrorist supplies.

FIGURE 5 Local integration: example red zones around a transit facility (Department of Transportation). Source: Transportation Research Board. 2004. P. 6 in NCHRP Report 525, Surface Transportation Security Volume 1—Responding to Threats: A Field Personnel Manual. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

URBAN SECURITY-UNIVERSITY INTERFACES AND COORDINATION

Universities can be a very useful component of the security defenses of a city and should be included in a coordinated approach to security. The university’s multiple functions and capabilities and their relation to urban security needs and tasks are shown in Box 2. Other educational and research entities, such as colleges, scientific institutes, and even specialized secondary schools, can also carry out a number of these functions, even if not to the same extent as a university. In various measures, all these institutions can—and many do—research issues pertinent to urban security and train and prepare personnel at all levels, from security staff to fire protection engineers, from structural engineers to decision makers (Hall, 2004). They can enhance public awareness of urban security and engender public trust, since they are generally perceived as neutral ground that can serve as a convener of discussions and examinations of urban security policies. A problem, however, for which for now appears to have no clear solution, is how to deal with access to sensitive, even if unclassified, information by faculty and students working on security projects.

|

Box 2 Capabilities and Potential Role of a University in Urban Security University Capabilities Education Training Research Consulting Public outreach Convening capability Databanks Facilities (special classrooms, laboratories) Policy studies University Responses to Urban Security Needs Preparation of leadership Specific training and perhaps also an ROTC for urban security (decision making, fire protection, infrastructure managers and engineers, distance learning) Research Information services Response to specific security demands |

PUBLIC AWARENESS, COMMUNICATION, AND EDUCATION

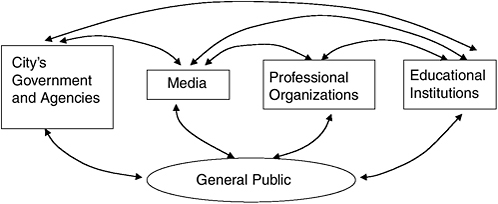

Beyond injuries, death, and physical damage, the greatest impact of terrorism is the psychological effect, as it amplifies manyfold the material effect of an attack and is difficult to counteract. The media have a major role in informing and educating the public and reducing the likelihood of panic. For instance, group psychology during an incident may lead to patterns of behavior that impede the response and strain logistic systems. Many media outlets are respected for their accuracy, even though some contribute to panic with sensationalism.

Even first responders and emergency management organizations might not communicate as effectively as the media, business, and NGOs, and might, at times, be mistrusted. Usually more trusted are institutions that naturally have an educational and instructional function, such as schools, colleges, universities, and professional societies. These institutions can reach into the general public at many levels, but thus far have been involved only to a limited extent in conveying to the public a realistic understanding of terrorist actions and their real impact. Thus, fostering their interaction with terrorism experts, researchers, first responders, and emergency managers is a critical component of a coordinated response to urban terrorism that needs to be addressed systematically and on a broad front (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 Public communication system synergies.

Employers, too, can contribute to the timely diffusion of important information to their dependents, and beyond them, as in a program encouraged by the OEM in New York City. The importance of such connections is evident, for instance, if one considers the lack of a realistic understanding by the general public about dirty bombs or of how to protect oneself from a biochemical attack that could lead to panic and other psychological impacts.

In this context, in the United States, the Office of Public Information of the National Academy of Engineering has conducted in several cities a series of well-reported awareness exercises, through simulated incidents, to prepare the media to report on an attack in a realistic and balanced way (see “News and Terrorism: Communicating in a Crisis” by Randy Atkins, in these proceedings).

IDENTIFICATION AND PROTECTION OF POTENTIAL TERRORIST SUPPLIES

A city possesses a broad array of resources—explosive material, biological agents, chemical factories and stores, radioactive sources, electronic devices, vehicles, fire weapons, and so forth—that can be misused by terrorists to attack objectives within the city (Box 3). In the United States, most of these supplies are in private hands. The responsibility for their protection—often not carried out very effectively—needs to be integrated with responsibilities of the public sector. Many potential supplies can be easily identified, but their protection is generally spotty and represents a critical dimension of an integrated approach to urban security. Also, coordination of the surveillance activities carried out at the neighborhood level by stores, individuals, and local organizations (such as in New York City the Business Improvement Districts [BIDs]) can be very helpful in complementing larger scale citywide endeavors carried out by police forces, industry, large business organizations, and specialized agencies.

|

Box 3 Potential Terrorist Resources in a City University, College, and Other Educational Institutions Electronic devices Chemical supplies Biological organisms Computers and access to networks Sensitive information Hospitals Chemicals Biological organisms Radioactive sources Transportation Infrastructure Cars Trucks Gasoline tanks Chemical Industry and Chemical Stores Toxic material Chemicals Explosives Poisons Energy Utilities Liquefied natural gas Gas pipelines Nuclear materials Financial Institutions Money Electronic Stores Devices (sensors, batteries, microwave generators) Ports Boats and ships Storage facilities Airports General aviation Libraries and Databanks Sensitive information Data tampering possibilities |

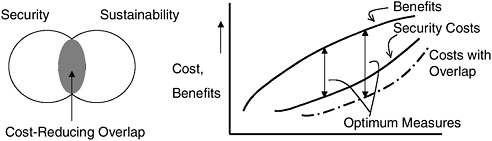

FIGURE 7 Security-sustainability integration.

DUAL-PURPOSE INTEGRATION

In the long term, the costs of urban security measures can become very large. To reduce the burden, it is increasingly important to find ways to integrate security measures with measures to satisfy other urban needs (NRC Committee on Science and Technology for Countering Terrorism, 2002). For instance, a long-term need of increasing concern to every city is to sustain its achievements in the future. The intersection of security and urban sustainability concerns identifies a common ground (Figure 7) that can reduce the combined cost of both. Thus a possible goal in developing an urban security system could be to integrate it as much as possible with sustainability measures. Figure 7 shows how, hypothetically, an overlap of the two can increase the benefit-cost difference of a security system. Examples of measures that can reduce urban security costs through integration with other needs include building designs; more effective maintenance; multipurpose guards and surveillance personnel; and multi- or dual-purpose sensors for security, traffic monitoring, air pollution, fire detection, and store surveillance.

TWO META-ISSUES: HUMAN-MACHINE AND SECURITY-CIVIL LIBERTIES INTERFACES

Human-machine integration and the interface of protection, laws, and civil liberties are two meta-issues critical to effective integration of urban security systems, but can only be briefly mentioned here. In terms of human-machine integration, the complexity of a city and the multiplicity of agencies and organizations involved in its security makes it imperative to utilize machines—software and hardware—as much as possible, to help decision makers, first responders, and others. The difficult question is how to create the most effective interfaces.

The interface between security and civil liberties is one of the most sensitive areas in urban security, as it ultimately determines the level of security and of

command and control a community is willing to accept in the creation of an effective response to terrorist threats. This requires a close dialogue between the exponents of the city’s civil values and the entities entrusted with the security of the city, to reach a modus operandi acceptable to both.

CONCLUSION

In brief, the extent to which different aspects of coordination and integration, such as those set forth in this paper, are carried out is a measure of the effectiveness of an urban security system. Coordination and integration are essential for reducing the probability and impact of terrorist attacks, but they are also essential for lessening the impact of natural disasters and for enhancing the long-term sustainability of a city.

REFERENCES

Bugliarello, G. 2003. Urban Security in Perspective. Technology in Society, November, 25(4): 499–507.

Hall, R. 2004. Protecting the Home Front. University Research Helps Keep Us Safe from Threats from Abroad. Prism, October 2004:44.

NRC Committee on Science and Technology for Countering Terrorism. 2002. Making the National Safer: The Role of Science and Technology in Countering Terrorism. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.