5

Drug-Drug Interactions

In addition to adverse events caused by use of a single drug, adverse events can be caused by drug interactions. Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) can make a medication less effective, cause unexpected side effects, or increase the action of a particular drug (FDA, 2003). They have the potential to cause significant harm to patients. Workshop participants discussed databases for recording and evaluating DDIs and ways to effectively communicate information about DDIs to practitioners and the public.

Sidney Kahn of Pharmacovigilance and Risk Management, Inc., noted that all drugs have actions that we do not fully understand. Robert Califf, Forum member, added that it is hard to define exactly what characterizes an interaction. He asserted that more research is needed to help healthcare providers make more informed decisions about how interactions occur and which ones are clinically significant. DDIs can be neutral, synergistic, or additive.

Preventing medication errors and making appropriate decisions about prescribing drugs for patients who are taking multiple medications will reduce adverse drug events (ADEs). In one study, 6.5 percent of pharmacist-screened admissions to a unit of a hospital’s medical service were drug related, and 67 percent of those cases were considered to be preventable (Howard et al., 2003). In a systematic review of 15 investigations, an earlier study found that a median of 7.1 percent of hospital admissions were drug related and 59 percent of those cases were preventable (Winterstein et al., 2002). The drugs most commonly associated with

preventable drug-related admissions are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), low-dose aspirin, beta-blockers, antiepileptics, diuretics, sulfonylureas, digoxin, inhaled corticosteroids, nitrates, and insulin (Howard et al., 2003). From a purely financial perspective, improving databases that monitor drug interactions is advantageous. Zynx Health representative Scott Weingarten asserted that a perfect drug information database could potentially save the U.S. health-care system $4.5 billion per year (Hillestad et al., 2005).

DRUG INTERACTION DATABASES

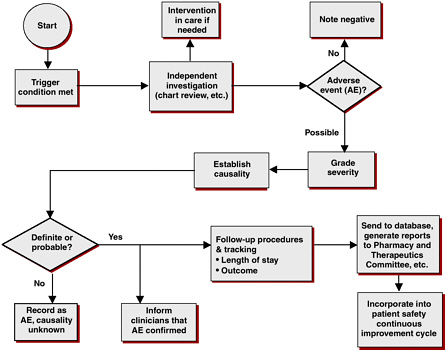

Although health-care systems have a structural framework in place for capturing and evaluating DDIs (see Figure 5-1), there are several problems with current information-capture systems. Multiple drug compendia exist, including Clinical Pharmacology Online, Drug Interaction Facts, and First Databank. However, these different systems often disagree on which

FIGURE 5-1 Adverse drug event surveillance: evaluation process in the Duke University Health System.

SOURCE: Peter Kilbridge, workshop presentation.

interactions having the greatest clinical importance, noted Jacob Abarca of the University of Arizona, College of Pharmacy.

A recent analysis conducted by Dr. Abarca noted limited agreement among drug-drug interactions considered to be of highest clinical importance (i.e., “major” drug-drug interactions) (Abarca et al., 2004). Four commonly used drug interaction compendia were chosen for the analysis: Evaluations of Drug Interactions (2001), Drug Interaction Facts (Mangini, 2001), Drug Interactions: Analysis and Management (Hansten and Horn, 2001), and the DRUG-REAX program (Moore et al., 2001). The analysis found 406 DDIs that were classified as being of highest clinical importance in at least one of these references. Only 2 percent were listed in all four compendia. The interclass correlation coefficient was 0.09, indicating very low agreement on the classification of major drug-drug interactions.

Russell Teagarden of Medco Health Solutions, Inc., recommended the establishment of uniform criteria for interactions and adverse drug reactions to reduce variability in defining what constitutes a major interaction. Mr. Teagarden, who contributed to Drug Interaction Facts (Mangini, 2001), pointed out that there is variability not only among sources but often within the groups working on each individual source as well. He reported that existing databases are not integrated, so clinically important information does not come from a single, easily accessed system. Establishing uniform criteria for drug interactions and adverse drug reactions may address robustness and concordance issues among information sources.

Dr. Kahn noted that a standardized terminology to uniformly evaluate interactions for their clinical importance is a necessity, “because if you can’t describe it, then you can’t analyze it.” Variable data quality makes a large portion of the collected knowledge unusable. Although databases can alert doctors and pharmacists to dangerous interactions, health-care providers are unable to respond to every alarm while still performing their clinical duties. Physicians can become subject to alert fatigue, which can cause notifications to be bypassed or switched off. Dr. Weingarten noted that some systems are overly sensitive, leading to many alarms; this leads to alert fatigue and decreased pharmacist productivity. The use of computerized systems creates an opportunity to issue alerts for potential DDIs. However, these alerts are embedded within other drug alerts that can make DDIs easy to ignore. Up to 88 percent of all drug alerts are overridden by community pharmacists (Chui and Rupp, 2000), said Dr. Abarca, and only one in nine alerts was deemed useful by providers, according to a 2005 study (Spina et al., 2005). “I think if we sent an alert to a pharmacy that said, ‘Your pharmacy is going to explode in 5 seconds,’ they would just override it and move on to the next prescription,” said Mr. Teagarden. However, pharmacists and providers consider DDI alerts more useful than other types of drug alerts (Abarca et al., 2006).

Mr. Teagarden and Dr. Weingarten agreed that pharmacists feel that the alerts are overly sensitive and not specific enough. To prevent physicians and pharmacists from being conditioned to ignore alerts, Dr. Abarca recommends that criteria be established for when to activate point-of-service alerts. “You could have the best, most comprehensive, most sensitive drug database in the world, but if it is turned off, it is not going to help patients,” said Weingarten. Stuart Levine of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices shared the results of two pharmacy system surveys conducted in 1999 and 2005. In the six-year period, very little changed in databases and information systems. In fact, said Dr. Levine, many systems showed a decrease in alert effectiveness.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) electronically share information about drugs with health-care providers, manufacturers, and heath plan sponsors. These linked databases could potentially provide valuable information about reducing harm from inefficacy, drug interactions, and adverse drug reactions. Mr. Teagarden explained that PBMs have a general interest in protecting patients from drug interactions and adverse events. In addition, smarter coverage decisions can be made from more robust and high-quality data. Mr. Teagarden expressed hope that technological advances in data storage will help PBMs take a greater role in preventing DDIs. However, he recommended that criteria should be established for alerting various stakeholders about drug interactions and adverse drug reactions.

Information about interactions can help plan sponsors decide what drugs they want to cover and where in the prescription formulary they should reside. Analysis of prescription claims data from a major PBM showed that 374,000 out of 46 million participants had been exposed to a potential drug interaction of clinical importance (Malone et al., 2005). Because coverage decisions are effected the same day a drug is placed on the market, noted Mr. Teagarden, any drug interaction database needs to be maintained and updated rapidly as patients are exposed to new products. Medco has found that plan sponsors also expect new information about existing drugs to be accessible and updated in a timely manner.

The potential for collaboration among PBMs, plan sponsors, and retail pharmacy networks could result in the development of a new, single database of interaction information. Even if such a product were used only for educational purposes, the groundwork for interinstitutional information sharing needs to be addressed. Mr. Teagarden expressed hope that the surveillance criteria established would detect adverse events and interactions earlier and also utilize prescribing information to detect drug interactions. “We might be able to pick up on something early whether it is identifying drugs expected to be used to treat an adverse reaction, or looking at prescribing patterns to detect drug interactions,” he said.

Mr. Teagarden acknowledged that the current systems and approaches between PBMs and retail pharmacy networks make this challenging. However with roughly 57,000 retail pharmacies making up one single network, added Mr. Teagarden, a significant volume of information is available.

COMMUNICATING DRUG INTERACTION INFORMATION

Patient education is an important step in the reduction of DDIs. For example, one Australian study found that education for physicians that was focused on better use of prescribed NSAIDS reduced the rate of hospital admissions for upper gastrointestinal bleeds by 70 percent (May et al., 1999). The more drugs a patient takes, the more likely is a DDI to occur. Some of the detailed scientific information from drug interaction studies is available to the public through the New Drug Application, which can be obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. However, not all information is disclosed in the public domain due to intellectual property and liability concerns of industry (Kraft and Waldman, 2001). Dr. Kahn stated, “There needs to be some kind of published database that is available to prescribers and the general public that actually contains real information on prioritization and frequency of potential interactions.” Dr. Abarca indicated that he did not know of any DDI information specifically for consumers available on the web. However, he discussed a University of Arizona project that developed a list of 16 websites that all met informal criteria for providing helpful information that is reviewed and obtained from independent sources. However, Dr. Weingarten pointed out that the content of these websites varies tremendously. “Some information is accurate and easy to understand, some is accurate and very difficult to understand without a medical background, and some information is just plain wrong,” he said.

The Internet is a powerful communication tool, capable of reaching large numbers of people while generating little overhead expense, but the many sources of information on the Internet offer inconsistent and sometimes inaccurate information about the dangers associated with drugs. On the other hand, this diversity prevents any one source from dominating the information available to consumers, regardless of its accuracy. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) could intervene if the market share of one particular drug information company became too large. Such government action took place when Medi-Span (owned by J. B. Laughery, Inc.) and First Databank merged in 1988. The FTC sued the Hearst Corporation, parent of First Databank, under charges that First Databank was using monopoly power to increase prices for customers who used its drug

information database (Lowe and Krulic, 2005). Hearst paid $19 million in settlement and divested Medi-Span (FTC, 2001).

Dr. Kahn proposed that a cross-disciplinary DDI working group be formed to create improved tools for communicating interactions and consequences. He believed that this group could identify and prioritize DDIs, develop a public database capable of receiving all new labeling information on drug interactions, perform an ongoing review of data from the FDA and the published literature, and possibly recommend specific interaction studies. He indicated that a model for the formation of such a group could be found in the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, an independent partnership of health-care organizations with the goal of reducing medical errors.