3

Coal Resource, Reserve, and Quality Assessments

Federal policy makers require sound coal reserve data in order to formulate coherent national energy policies. Accurate and complete estimates of national reserves are needed to determine how long coal can continue to supply national electrical power needs, and to determine whether coal has the potential to replace other energy sources, such as petroleum, that may be less reliable or less secure. The coal production and utilization industries—as well as the transportation industry, equipment manufacturers and suppliers, engineering and environmental consultants, federal and state policy makers, financial institutions, and electric transmission grid planners and operators—all require accurate coal reserve estimates for planning. The location, quantity, and quality of coal reserves are critical inputs for determining where end-user industries should be located and for understanding the infrastructure (e.g., trains, barges, haul roads, silos, preparation facilities, power plants, pipelines, electrical transmission lines) that will be needed to support coal production and use. An accurate, comprehensive assessment of the nation’s coal resources is essential for informed decisions that will allow the use of this resource so that negative environmental and human health impacts are minimized and there can be an orderly transition from one region to another as the reserves being mined are exhausted. Any substantial increase—perhaps even doubling of current coal production and utilization, as implied by some of the scenarios presented in Chapter 2—will spawn technological, economic, social, environmental, and health issues that will be better anticipated and more efficiently addressed if the location, quantity, and quality of the coal that will be mined over the next several decades are known.

The United States is endowed with a vast amount of coal. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that there are nearly 4 trillion tons of total coal

resources in the United States. (Averitt, 1975). However, this estimate has little practical significance because most of this coal cannot be mined economically using current mining practices. A more meaningful figure is the ~267 billion tons of Estimated Recoverable Reserves (ERR) (EIA, 2006a) that is the basis for the commonly reported estimate that the United States has at least 250 years of minable coal.1 This chapter addresses two major questions to place existing estimates of the amount of usable coal into a broad perspective:

-

Are estimates of available coal reliable, and are they good enough to allow federal policy makers to formulate coherent national energy policies?

-

Can coal reserves in the United States produce the total 1.7 billion tons per year of coal required in 2030 if the Energy Information Administration (EIA) reference case described in Chapter 2 becomes a reality?

The answer to the second question, whether the United States has enough minable coal to meet the projected demands in the EIA reference case, is definitely yes. Coal mining companies report at least 19 billion tons of Recoverable Reserves at Active Mines (EIA, 2006a), and the coal industry reports about 60 billion tons of reserves held by private companies (NMA, 2006a). If recoverable reserves on private, federal, and state lands are added, there is no question that sufficient minable coal is available to meet the nation’s coal needs through 2030. Looking further into the future, there is probably sufficient coal to meet the nation’s needs for more than 100 years at current production levels. However, it is not possible to confirm that there is a sufficient supply of coal for the next 250 years, as is often asserted. A combination of increased rates of production with more detailed reserve analyses that take into account location, quality, recoverability, and transportation issues may substantially reduce the estimated number of years supply. This increasing uncertainty associated with the longer-term projections arises because significant information is incomplete or unreliable. The data that are publicly available for such projections are outdated, fragmentary, or inaccurate—these deficiencies are elaborated below. Because there are no statistical measures to reflect the uncertainty of the nation’s estimated recoverable reserves, future policy will continue to be developed in the absence of accurate estimates until more detailed reserve analyses—which take into account the full suite of geographical, geological, economic, legal, and environmental characteristics—are completed.

RESOURCE AND RESERVE DEFINITIONS

The terms coal resources and coal reserves are commonly misused and mistakenly interchanged. Coal resource is a more general term that describes

naturally occurring deposits in such forms and amounts that economic extraction is currently or potentially feasible (Wood et al., 1983). Coal reserve is a more restrictive term describing the part of the coal resource that can be mined economically, at the present time, given existing environmental, legal, and technological constraints (Wood et al., 1983). Coal reserve estimates are often considered the more important parameter because they quantify the amount of recoverable coal. However, coal resource estimates are also important because they are the basis for reserve estimates, and in areas where the data required for defining reserves are missing or inadequate, they provide an indication of the amount of coal in the ground.

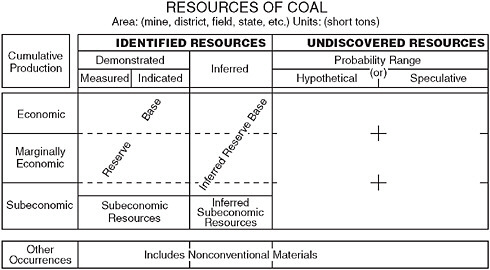

The coal resource and reserve classification system currently in use in the United States (Figure 3.1) has undergone more than a century of development. The current system was adopted in 1976 by the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines (USDOI, 1976) and modified in USGS Circular 891 (Wood et al., 1983). Circular 891 established a uniform foundation for coal resource and reserve assessments by providing standard definitions, criteria, guidelines, and methods. Circular 891 defined coal resource and reserve classes according to their degree of geological reliability (horizontal axis) and economic feasibility (vertical axis) (Figure 3.1), with reliability categories based on the distance from data

FIGURE 3.1 Definition of coal resource and reserve classes based on the geological reliability (horizontal axis) and economic viability (vertical axis) of resource estimates. This diagram, often referred to as the McKelvey diagram after a former director of the USGS, represented the state of the art for resource depiction at the time of its publication. SOURCE: Wood et al. (1983).

points (¼ mile for “measured,” ¾ mile for “indicated,” 3 miles for “inferred,” and >3 miles for “hypothetical” reserves). The speculative category (Figure 3.1) applies where a geological setting that is likely to contain coal has not yet been explored. State geological surveys working in cooperation with the USGS have been encouraged to adopt this system.

SOURCES OF COAL RESOURCE AND RESERVE INFORMATION

The two primary federal agencies that provide resource and reserve information are the Energy Information Administration in the Department of Energy, and the U.S. Geological Survey in the Department of the Interior.

U.S. Energy Information Administration

The EIA is responsible for maintaining Demonstrated Reserve Base (DRB) data (Box 3.1), the basis for assessing and reporting U.S. coal reserves. The DRB evolved from work performed by the U.S. Bureau of Mines that was published as Information Circulars 8680 and 8693 (USBM, 1975a, 1975b). These circulars contain estimates of DRB tonnage remaining in 1971, reported by county and

|

BOX 3.1 U.S. Demonstrated Reserve Base (DRB) The DRB is a collective term for the sum of coal in both “measured” and “indicated” resource categories (see Figure 3.1), and includes the following:

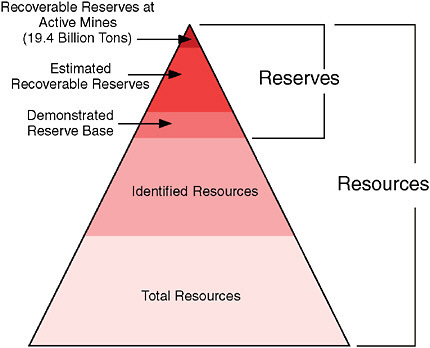

The DRB represents that portion of the identified resources of coal from which reserves are calculated (see Figure 3.2) and is thus a derived value using arbitrary limits and based on limited coal industry data. More recent (2005) numbers for each category except total resources are presented in Table 3.1. The concept that coal resource and reserve tonnages will sequentially decrease corresponding to greater data reliability and increased confidence in economic recoverability, as portrayed in Figure 3.2, is fundamentally correct. However, there is no justification for the estimates to have more than two significant figures, nor are the sharp boundaries between the different reserve and resource categories realistic. These boundaries will shift up or down (decreasing or increasing tonnage estimates) depending on the availability of new information or particular changes or trends in technology and economics, as well as environmental constraints, transportation availability, and demographic shifts. |

coal bed and by sulfur content. The EIA became responsible for maintaining the DRB database in 1977 under the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-91), which required the EIA to carry out a comprehensive and unbiased data collection program and to disseminate economic and statistical information to represent the adequacy of the resource base to meet near- and long-term demands. Since 1979, EIA has published updates to the DRB by adding additional reserve/resource data from state coal assessments and by depleting the DRB according to the amount of annual coal production. The DRB represents a subset of total national coal resources, because it includes only coal that has been mapped, that meets DRB reliability and minability criteria, and for which the data are publicly available (see Box 3.1 and Figure 3.2). The EIA also reports Estimated Recoverable Reserves (ERR). The ERR is derived from the DRB by applying coal mine recovery and accessibility factors by state to the DRB. The ERR is categorized by state, Btu (British thermal unit) value, sulfur content, and mining type—it is the most widely reported and frequently quoted estimate of U.S. coal reserves.

FIGURE 3.2 Triangle depicting U.S. coal resources and reserves, in billion short tons, as of January 1, 1997. The darker shading corresponds to greater relative data reliability. SOURCE: EIA (1999).

The EIA is authorized under federal statutes to collect confidential reserve data from coal companies with active mines. These reserve data are compiled into the Recoverable Reserves at Active Mines (RRAM) database. Although RRAM data are updated annually, they represent only a fraction of the reserves controlled by mining companies. The business complexities of resource holding companies, landowners, lease holders, and production companies make it difficult to collect comprehensive RRAM data, and these data are therefore too limited for mid- and long-range planning. There is no direct relationship between the ERR and the RRAM because they are determined from different data sets.

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

The USGS has responsibility for mapping and characterizing the nation’s coal resources, in cooperation with agencies that have land and resource management responsibilities (e.g., Bureau of Land Management, Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement) and agencies that use USGS resource projections (e.g., EIA). The USGS is in the process of undertaking a systematic inventory of the U.S. coal reserve base to determine how much of the domestic coal endowment is technologically available and currently economic to produce. Assessments of coal quality are a core component of the USGS energy resources program research portfolio (NRC, 1999). The USGS has recently focused its efforts on accumulating data on coal quality for the feed coals and coal combustion products from individual coal-fired power plants, including assessments of elements in coal that can potentially have adverse effects on environmental quality and/or may be slated for regulation. To accomplish its goals, the USGS has a number of programs—in collaboration with other federal and state agencies—that are intended to better characterize the nation’s coal endowment.

National Coal Resources Data System. The USGS analyzes coal samples and collects geological data in cooperation with coal-producing states. Thousands of coal samples have been analyzed, and hundreds of thousands of data points describing coal geology, thickness, and depth have been collected. Although this program is still active, it has been scaled down in the past decade because of restricted funding.

Coal Availability Studies. The USGS and state geological surveys have a cooperative program to assess the proportion of identified coal resources that are available to the coal industry for mining. These studies take into account regulatory considerations that restrict mining (e.g., distribution of public lands, streams, or oil and gas wells), as well as technological issues that impede mining such as thin coal seams, mine barriers, seams that are too closely spaced for all to be mined using existing methods, and faulted areas. Thus far, 108 coal availability studies have been completed,2 and these suggest that less than 50 percent of identified coal resources are available for mining.

Coal Recoverability Studies. This program takes the results of coal availability studies and applies engineering criteria to determine minability and recoverability (e.g., Carter et al., 2001). These resource calculations differ from the others described above in that they take in-seam rock partings3 into account and estimate the percentage of recoverable coal according to anticipated mining methods and coal washability characteristics. A total of 65 areas in 22 coal fields have been analyzed, and these studies suggest that 8 to 89 percent of the identified resources in these coal fields are recoverable and 5 to 25 percent of identified resources may be classified as reserves.4 Because they are based on site-specific criteria, these studies provide considerably improved estimates compared to the ERR. Ultimately, comprehensive coal recoverability studies would allow cost curves to be generated so that reserve quantities could be determined for different cost levels.

National Coal Resource Assessment. In 1995, the USGS began the National Coal Resource Assessment (NCRA) for major coal beds in selected coal basins by compiling data from adjoining states into a single assessment in GIS (geographic information system) format. The NCRA estimates only the major coal-producing beds and therefore cannot easily be compared with the DRB, which is aggregated for all beds. Some of the NCRA assessments have been updated using coal availability and recoverability criteria to yield basin-wide reserve estimates.

Inventory Studies. The USGS recently initiated a systematic inventory of the U.S. coal reserve base, to determine the subset of in-place resources that is technically and economically recoverable on a basin-wide scale. An initial reserve estimate for the Gillette coalfield of the Powder River Basin is expected in 2007, to be followed by reserve estimates for the entire Powder River Basin by the end of 2008.

Other Sources of Coal Resource and Reserve Information

Although most coal-producing states have geological surveys that collect data on their coal resources, in most cases these organizations lack the personnel and funding for major coal resource and reserve investigations. Most coal resource investigations have been undertaken in cooperation with the USGS, Bureau of Land Management, or the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. For this reason, state geological surveys typically only evaluate in-place tonnage and do not estimate recoverability—this has been largely left to the USGS and EIA.

Mining companies generate detailed reserve estimates for the coal they control or are interested in obtaining. Companies consider these data to be proprietary, and consequently they are not available for government resource and reserve studies except for the reserve estimates that have to be reported at

operating mines. Similarly, some states use industry data to prepare coal reserve estimates on unmined reserves for tax purposes, but these data are not publicly available.

The Keystone Coal Industry Manual is a private publication for the coal industry that has been published annually since 1918. It contains descriptions of the coal resources and geology of coal fields for each coal-producing state, describing coal bed geology, stratigraphy, thickness, quality, rank, mining methods, and identified resources (measured, indicated, and inferred). The state sections of the Keystone Coal Industry Manual are updated on an irregular basis, generally by state geological survey geologists.

U.S. COAL RESOURCE AND RESERVE ESTIMATES

The current estimates of total U.S. coal resources and reserves reported by the EIA are shown in Table 3.1. The ERR (Figure 3.2)—approximately 54 percent of the DRB—is calculated based on accessibility factors (by coal-producing region) and recoverability factors at existing mines. ERR and DRB estimates by state and mining method are presented in Appendix D; a subset of these data for the 15 states containing the largest reserves is shown in Table 3.2.

Limitations of Existing Coal Resource and Reserve Estimates

Old and Out-of-Date Data. By definition, the DRB does not represent all of the coal in the ground (EIA, 2006b). It represents coal that has been mapped, that meets DRB reliability and minability criteria, and for which the data either are publicly available or have been provided by companies under confidentiality provisions. The DRB was initiated in the 1970s, and consequently the majority of DRB data were compiled based on the geological knowledge and mining technology available more than 30 years ago. Although the DRB has been updated in 1989, 1993, 1996, and 1999 to incorporate reserve depletion data and limited more recent reserve data (EIA, 1999), the underpinning data remain those of the original 1974 study. The data on Identified Resources and Total Resources

TABLE 3.1 U.S. Coal Resources and Reserves in 2005

|

Category |

Amount (billion short tons) |

|

Recoverable Reserves at Active Mines |

19 |

|

Estimated Recoverable Reserves |

270 |

|

Demonstrated Reserve Base |

490 |

|

Identified Resources (from Averitt, 1975) |

1,700 |

|

Total Resources (above plus undiscovered resources) |

4,000 |

|

NOTE: The relationships between these categories are depicted in Figures 3.1 and 3.2. |

|

TABLE 3.2 Estimated Recoverable Reserves and Demonstrated Reserve Base for the 15 States with Largest Reserves, by Mining Method for 2005 (million short tons)

|

|

Underground Minable Coal |

Surface Minable Coal |

Total |

|||

|

State |

ERR |

DRB |

ERR |

DRB |

ERR |

DRB |

|

Alabama |

508 |

1,007 |

2,278 |

3,198 |

2,785 |

4,205 |

|

Alaska |

2,335 |

5,423 |

499 |

687 |

2,834 |

6,110 |

|

Colorado |

6,015 |

11,461 |

3,747 |

4,762 |

9,761 |

16,223 |

|

Illinois |

27,927 |

87,919 |

10,073 |

16,550 |

38,000 |

104,469 |

|

Indiana |

3,620 |

8,741 |

434 |

742 |

4,054 |

9,483 |

|

Kentucky |

7,411 |

17,055 |

7,483 |

12,965 |

14,894 |

30,020 |

|

Missouri |

689 |

1,479 |

3,157 |

4,510 |

3,847 |

5,989 |

|

Montana |

35,922 |

70,958 |

39,021 |

48,272 |

74,944 |

119,230 |

|

New Mexico |

2,801 |

6,156 |

4,188 |

5,975 |

6,988 |

12,131 |

|

North Dakota |

— |

— |

6,906 |

9,053 |

6,906 |

9,053 |

|

Ohio |

7,719 |

17,546 |

3,767 |

5,754 |

11,486 |

23,300 |

|

Pennsylvania |

10,710 |

23,221 |

1,044 |

4,251 |

11,754 |

27,472 |

|

Texas |

— |

— |

9,534 |

12,385 |

9,534 |

12,385 |

|

West Virginia |

15,576 |

29,184 |

2,382 |

3,775 |

17,958 |

32,960 |

|

Wyoming |

22,950 |

42,500 |

17,657 |

21,319 |

40,607 |

63,819 |

|

Other states |

8,667 |

12,226 |

2,535 |

3,861 |

11,202 |

16,086 |

|

U.S. Total |

152,850 |

334,876 |

114,705 |

158,059 |

267,554 |

492,935 |

|

NOTE: Data for all states are shown in Appendix D. SOURCE: EIA (2006b). |

||||||

currently published by the EIA are estimates from 1974 that were presented by Averitt (1975) and have not been updated.

Another shortcoming is the restricted use of modern geospatial technology for reserve data management. The current system provides data tables and compiled estimates without supporting map and geographic information. The use of modern GIS-based data management systems would have the advantage of being map-based, reproducible, and updateable as new data become available. In addition, the coal reserve and resource database that supports EIA estimates is out-of-date, and much of the legacy data may be irretrievable due to changes in computer technology in the 30+ years since the DRB was initiated.5

Mined Coal Not Included in DRB. Wood et al. (1983) set guidelines for the seam thicknesses and mining depths needed for coal to qualify for the DRB, stipulating that only measured and indicated resources meeting certain conditions could be included (e.g., criteria in Box 3.1). Coal beds are currently being

mined that are too deep or too thin to qualify as a part of the DRB under these criteria—some underground mining is being carried out at greater than 2,500-foot depths, and surface (and some underground) coal seams less than 28 inches thick are being mined in the eastern states. Mining technology improvements have resulted in resources not presently included in the DRB becoming economically recoverable and therefore eligible for inclusion in the DRB and the ERR.

Restricted Availability of Industry Data. The EIA, USGS, and state geological surveys typically do not have access to the large amount of private industry exploration and development data that include extensive drilling and active mining information. Although mining company data are occasionally made available for government coal resources studies, federal and state agencies are in general limited to publicly available coal bed related information such as outcrops, road cuts, oil and gas wells, water wells, and maps of abandoned mines. With limited budgets, many coal-producing states have been unable to explore all of their coal resources, resulting in substantial resources being included in the “identified” category when additional information (e.g., more closely spaced data) could result in these resources being confirmed in the DRB and ERR.

Inferred and Undiscovered Resources Ignored. Coal seams are found in a variety of geologic settings and their characteristics, including variability in thickness and continuity, can differ markedly from basin to basin. Therefore, any definition of geological reliability (measured, indicated, and inferred) that is intended for the entire country is not as precise as a system that takes into account the geological differences between regions and between coals of different geological ages. Although Wood et al. (1983) permit practitioners to specify customized dimensions for reliability circles to reflect the variability of coal deposits, most states use the recommended ¼-, ¾-, and 3-mile data spacing (for measured, indicated, and inferred, respectively) to facilitate comparisons with other estimates. This means that reserves existing ¾ mile to 3 miles from a point of coal measurement (e.g., a drill hole or outcrop) are classified as “inferred,” and all coal existing beyond a 3-mile radius falls into the “undiscovered” category. As a result, a large amount of coal in the “inferred” category is not in the DRB and is not included in ERR calculations.

Alaska provides an example of potential coal reserves not accounted for by EIA statistics. The most recent comprehensive state coal resource assessment indicates that total hypothetical coal resources in Alaska exceed 5.5 trillion short tons (Merritt and Hawley, 1986). By comparison, the EIA-USGS estimate of total U.S. resources, including hypothetical measures, is 4 trillion tons. Alaska accounts for only 1 billion tons in the 2004 DRB estimate, even though state experts consider that coal reserves in Alaska may possibly surpass the total coal resources in the lower 48 states.

Coal Quality Issues. The uncertainties concerning resource and reserve estimates also apply to the grade or quality of the coal that will be mined in the future. At present, we lack methods to project spatial variations of many impor-

tant coal quality parameters beyond the immediate areas of sampling (mostly drill samples). Almost certainly, coals mined in the future will be lower quality because current mining practices result in higher-quality coal being mined first,6 leaving behind lower-quality material (e.g., with higher ash yield, higher sulfur, and/or higher concentrations of potentially harmful elements). The consequences of relying on poorer-quality coal for the future include (1) higher mining costs (e.g., the need for increased tonnage to generate an equivalent amount of energy, greater abrasion of mining equipment); (2) transportation challenges (e.g., the need to transport increased tonnage for an equivalent amount of energy); (3) beneficiation challenges (e.g., the need to reduce ash yield to acceptable levels, the creation of more waste); (4) pollution control challenges (e.g., capturing higher concentrations of particulates, sulfur, and trace elements; dealing with increased waste disposal); and (5) environmental and health challenges. Improving the ability to forecast coal quality will assist with mitigating the economic, technological, environmental, and health impacts that may result from the lower quality of the coal that is anticipated to be mined in the future.

INTERNATIONAL COAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENTS

The World Energy Council (WEC) publishes, on a triennial schedule, a Survey of Energy Resources, the most recent of which is the twentieth edition (WEC, 2004). This survey includes fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas), uranium and nuclear fuel, and renewable resources. Where relevant, tables are published of fossil fuel resources and reserves, with data derived from member countries of the WEC and from non-WEC sources. The WEC data tables for coal are widely accepted, used, and quoted by numerous agencies and entities (e.g., IEA, 2004; BP, 2006; EIA, 2006f). Collecting reliable and comprehensive data on a worldwide basis, from more than 75 countries, presents a significant challenge for the authors of the publication—in particular, they note that resource and reserve definitions can differ widely among countries (WEC, 2004). In an attempt to improve the data on resources and reserves of fossil fuels and uranium, the WEC has been coordinating with the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) seeking to adopt a uniform set of definitions; however, uniform definitions were not in place for the 2004 edition. International data for proved recoverable reserves presented by WEC (2004) are listed in Appendix D.

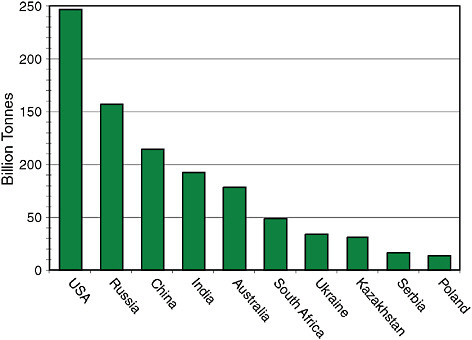

The 10 countries that reported the largest quantity of proved recoverable reserves (Figure 3.3) have, in aggregate, 92 percent of the world’s proved recoverable reserves. The top three countries—the United States, the Russian Federation, and China—contain 57 percent of proved recoverable reserves. China, which produced 40 percent more coal in 2002 than the United States, reported proved

FIGURE 3.3 The 10 countries reporting the largest amount of proved recoverable reserves in 2002. SOURCE: Data from WEC (2004).

recoverable reserves that were only 46 percent those of the United States—an anomalously low value (WEC, 2004).

It is possible to undertake the academic exercise of dividing the worldwide proved recoverable reserves by the total world coal production for the same year, to obtain about 188 years of production. Although correct mathematically, this number is of little value because it suffers from the same inconsistencies and deficiencies in input parameters as the equivalent calculation for the United States. Like the United States, the world has vast amounts of coal resources, and like the United States, a clear picture of global coal reserves is difficult to ascertain. In part, this is due to strategic concerns about revealing information on domestic energy resources, absence of government recognition of the importance of such information, the lack of trained personnel or funding to carry out such studies, and differences in methodology and terminology.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION—COAL RESOURCE, RESERVE, AND QUALITY ASSESSMENTS

Federal policy makers require sound coal reserve data to formulate coherent national energy policies. Accurate and complete estimates of national reserves

are needed to determine whether coal can continue to supply national electrical power needs and to determine whether coal has the potential to replace other energy sources that may become less reliable or less secure.

-

The United States is endowed with a vast amount of coal. Despite significant uncertainties in generating reliable estimates of the nation’s coal resources and reserves, there are sufficient economically minable reserves to meet anticipated needs through 2030. Further into the future, there is probably sufficient coal to meet the nation’s needs for more than 100 years at current rates of consumption. However, it is not possible to confirm the often-quoted suggestion that there is a sufficient supply of coal for the next 250 years. A combination of increased rates of production and more detailed reserve analyses that take into account location, quality, recoverability, and transportation issues may substantially reduce the estimated number of years of supply. Because there are no statistical measures to reflect the uncertainty of the nation’s estimated recoverable reserves, future policy will continue to be developed in the absence of accurate estimates until more detailed reserve analyses—which take into account the full suite of geographical, geological, economic, legal, and environmental characteristics—are completed.

-

The Demonstrated Reserve Base (DRB) and the Estimated Recoverable Reserves (ERR), the most cited estimates for coal resources and reserves, are based on methods for estimating resources and reserves that have not been reviewed or revised since their inception in 1974. Much of the input data for the DRB and ERR are also from the early 1970s. These methods and data are inadequate for informed decision making. New data collection, in conjunction with modern mapping and database technologies that have been proven to be effective in limited areas, could significantly improve the current system of determining the DRB and ERR.

-

Coal quality is an important parameter that significantly affects the cost of coal mining, beneficiation, transportation, utilization, and waste disposal, as well as the coal’s sale value. Coal quality also has substantial impacts on the environment and human health. The USGS coal quality database is largely of only historic value because relatively few coal quality data have been generated in recent years.

Recommendation: A coordinated federal-state-industry initiative to determine the magnitude and characteristics of the nation’s recoverable coal reserves, using modern mapping, coal characterization, and database technologies, should be instituted with the goal of providing policy makers with a comprehensive accounting of national coal reserves within 10 years.

The U.S. Geological Survey already undertakes limited programs that apply modern methods to basin-scale coal reserve and quality assessments. The USGS

also has the experience of working with states to develop modern protocols and standards for geological mapping at a national scale through its coordinating role in the National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program. The USGS should be funded to work with states, the coal industry, and other federal agencies to quantify and characterize the nation’s coal reserves. Recognizing the urgency of this requirement, the committee stipulated that this comprehensive accounting should be completed within 10 years, although it accepts that the exact time frame may be shortened by the lead agency on approval of the project. The committee estimates that this will require additional funding of approximately $10 million per year.