2

Overview of Adolescent Health Issues

A logical starting point for a discussion of adolescent health care would be to define adolescence, but in practice the boundaries of this phase of life are not precise. Even within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) several definitions are in use, as Andrea MacKay (National Center for Health Statistics) pointed out to workshop participants. Students in grades 9 through 12 are covered in the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, for example, while the Healthy People 2010 health objectives address 10- to 19-year-olds, with some attention to 20- to 24-year-olds, and the Healthy People in Every Stage of Life Program defines adolescents as 12- to 19-year-olds.1 Other research programs related to adolescents at the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality offer no definition. In the face of this confusion, Robert Blum (The Johns Hopkins University) exhorted the committee to define adolescence, and MacKay made a case for settling on ages 10, the lower bound of puberty, to 19, the age at which most adolescents embark on adult paths, such as college, employment, military service, marriage, or parenthood.

The question is more than semantic. Social and cultural changes have meant that more and younger children face challenges and health problems once very rare for them, while issues typical of adolescence may

|

1 |

National Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, available: <http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm>; Healthy People 2010 health objectives, available: <http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/tableofcontents.htm>; Healthy People in Every Stage of Life Program goals, available: <http://www.cdc.gov/osi/goals/people.html>. |

persist into the early twenties. The average age of the onset of puberty has declined over the last century, occurring by age 10 for many children, while neuroscience has established that cognitive development is not complete until the early twenties. At the same time, as the world has become more complex, the social concept of adolescence is extending into what was once considered adulthood, and young people are assuming adult roles and responsibilities later. Such changes have challenged researchers and practitioners to sustain a coherent conceptual picture of adolescence.

To highlight the need, Blum took note of two contrasting models of care: one focused on children, and the other on adults. In a pediatric approach to medicine, the parent is the responsible agent and the focus is on nurturing the patient in a family context. In an adult-centered approach, the patient is the responsible agent; the provider offers information with which the patient makes decisions, and the focus is on the individual, not the family.2 The treatment of adolescents does not fit either model well, and their needs change as they progress through this stage. Despite the complexity of this stage of life, the significant developmental and cognitive changes it encompasses, and the important implications of adolescent health and behavior patterns for adult health status, adolescence is the subject of less research than any other age group, Jonathan Klein (University of Rochester Medical Center) pointed out. Perhaps as a result, while some practitioners specialize in caring for adolescents, their numbers are few—less than 1 percent of primary care physicians who may see adolescents are board-certified specialists in adolescent medicine, according to data from the American Board of Medical Specialties supplied by Klein.

ADOLESCENT HEALTH STATUS

Regardless of the boundaries of adolescence, however, a variety of health issues affect this group, according to MacKay, who provided an overview of trends in adolescent health. The good news is that mortality rates for adolescents ages 15 through 19, both from injury and from all other causes, declined between 1980 and 2004, according to the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. Currently, the rate of death from all causes for this age group is approximately 65 per 100,000. Nevertheless, adolescence is a much more dangerous phase of life than childhood. Despite the improved mortality rates, three major threats to adolescents’

health remain serious problems: death by injury, primarily by firearm or motor vehicle crash; attempts at suicide; and complications that may develop in adulthood due to overweight. Specifically:

-

The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, another CDC study, tracking suicide ideation (thoughts of suicide) and suicide attempts among students in grades 9 through 12, found that despite marked declines since 1991 in the numbers of adolescents who have “seriously considered” suicide, the rates of attempts (almost 17 percent) and attempts that cause injury (almost 2.5 percent) remained steady during that time period.

-

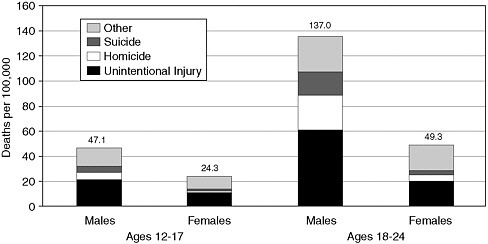

Mortality rates for adolescents have declined in recent years, and the causes have fluctuated. Predominant risk factors include motor vehicle crashes and firearm-related injuries. Older adolescents are at higher risk than younger adolescents of mortality caused by motor vehicle crashes and firearm-related injuries. Young men are at higher risk of mortality than young women for all causes, as shown in Figure 2-1.

-

The CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, tracking rates of overweight among adolescents ages 12 to 19 since 1966, has identified a steady increase since the 1976–1980 survey, when roughly 5 percent of adolescents were overweight. According to the 2003–2004 survey, roughly 18 percent of adolescents were overweight that year, and diseases including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and depression are associated with obesity in that age group (Daniels, 2006).

In addition to suicide attempts, death by injuries, and an epidemic of obesity, exposure to violence and victimization, untreated dental caries, and reproductive health issues were also identified by MacKay as troubling indicators of adolescent health status. Violent crime victimization rates among adolescents and young adults (ages 12–24) have generally decreased since 1995, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey, but violence remains a serious concern, with approximately 2 million adolescents (ages 12–24) having reported exposure to violent crimes in 2004. From 2001 to 2004, the proportion of young adults (ages 20–24) with untreated dental caries was 50 percent higher than that of adolescents ages 10–19, according to the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Overall, 23 percent of adolescents and young adults had at least one untreated dental caries or infection.

Reproductive and sexual health is another area of significant need for adolescents, who particularly need contraceptive and family planning

FIGURE 2-1 Mortality by cause, gender, and age group, ages 12 to 24, United States, 2003. Data from the 2003 Fatal Injury Reports of the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

SOURCE: Park et al. (2006). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

care. Although both pregnancy and birth rates for adolescents 15 to 19 have declined since 1990, there are still nearly 80 pregnancies and between 20 and 80 live births per 1,000 adolescents each year (birth rates vary by race and ethnicity as well as other factors). In 2002, over 80 percent of sexually active young women ages 15 to 19 reported use of some form of contraception at last intercourse, according to the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth. Chlamydia remains the most common bacterial cause of sexually transmitted diseases for adolescents ages 15 to 19, according to the Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Surveillance collected by the National Center for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention from the CDC. Young women had higher rates of chlamydia than their male counterparts. Gonorrhea and syphilis are also frequently reported. Older adolescents are at a higher risk of sexually transmitted disease than younger adolescents. Young women who become pregnant and all sexually active adolescents need medical care. The need for this type of health care affects all groups and subgroups.

From MacKay’s perspective, the broad category of mental health and risk behaviors provides an important key to adolescent health that must be considered along with medically related measures of health. A significant proportion of adolescents’ health problems relate to sexual activity;

use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs; driving while impaired; poor diet; mental disorders; and exposure to weapons, according to the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In 2002 more than 80 percent of young women ages 18 and 19 and more than 50 percent of those ages 15 to 17 were sexually active. More than 80 percent of those young women (ages 15–19) were using birth control, but nearly 20 percent were not. Indicators for many of these behaviors have shown some improvement. For example, the rate of frequent smoking3 dipped below 10 percent in 2005; the rate of frequent alcohol use has edged down slightly since 1991, to approximately 25 percent; and the rate of current marijuana use has also slipped down to 20 percent, after a substantial increase in the 1990s.4 Despite these modest improvements, however, risky behaviors are still among the biggest issues in adolescents’ health, and the rates are still high enough to be significant public health concerns.

A final area of concern is adolescents’ access to quality health care. For a host of reasons (explored in greater detail in later sections), many adolescents have no insurance at all or insufficient health insurance, or they lack adequate information about coverage for which they may be eligible, such as Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). According to the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, low-income adolescents are least likely to have health insurance—20 percent of adolescents in families below the poverty level have no insurance, compared with 8 percent of those in families at twice that level or greater. Older adolescents, ages 18 and 19, are most likely to lack coverage, while significant numbers of poor younger adolescents are covered only through public programs. Adolescents particularly tend to have dental care, routine outpatient care, mental health care, and reproductive health services that are inadequate.

Thus, as MacKay noted, many of the risks to adolescents’ health are primarily caused by social and behavioral factors that require attention to preventive care, risk, environmental factors, and protective behaviors. Physically, adolescents are generally healthy and they are less prone to many illnesses than younger children are. Nevertheless, many of the behaviors that compromise adult health, such as diets and inadequate exercise that lead to cardiovascular disease and obesity; experimentation

with tobacco, alcohol, and drug use that can lead to addiction; and reliance on violent behaviors to address conflict and stress, are habits formed during adolescence. These behaviors and patterns have serious long-term consequences because they are linked to conditions, such as diabetes and cardiac disease, that are serious threats to individuals’ health, quality of life, and life span, as well as significant public health threats.

CURRENT STATE OF CARE

With this picture of adolescent health in place, the focus of the research workshop shifted to an examination of the ways in which care is provided for this group.

Statistical Overview

Jonathan Klein presented a statistical overview of the care adolescents are currently receiving. First, the majority of adolescents (or their parents) report that they have a usual source of primary care (94 percent of young women and 91 percent of young men), although they are somewhat less likely than younger children to have had a primary care visit in the past year (Klein, 1997). However, a closer look at the nature and quality of health services for adolescents reveals some deficits. While household survey results indicate that most adolescents receive their primary care in a doctor’s office or clinic, 10 percent of young women and 13 percent of young men rely on the hospital or the emergency room as their usual source of care (Klein, 1997). Over 90 percent say they have had a well-patient visit in the past two years (Klein, 1997), but only 49.2 percent have received care that followed recommended guidelines, such as those for annual well-patient visits, confidential and comprehensive health screening, and immunizations (Selden, 2006).5

Most guidelines for adolescent health care stress the importance of talking with adolescent patients without a parent present in the examination room. Yet just 53 percent of young women and 62 percent of young men have had the chance to speak privately with a doctor when they needed to, and 39 percent of young women and 24 percent of young men have been too embarrassed to bring up a topic about which they had questions during an appointment, according to data from Klein (1997). He showed significant discrepancies between adolescents wanting to dis-

cuss a range of issues—including eating disorders, drugs, contraception, abuse, and smoking—and ever having actually done so with a health care provider (Klein and Wilson, 2002).

A quarter to a third of adolescents have gone without care they needed (Klein, 1997), and approximately 19 percent reported having done so in the past year (Ford, Bearman, and Moody, 1999; Lehrer et al., 2007). Moreover, it is those who need care the most (such as low-income adolescents and those with poor health status, depression, or a history of abuse) who are most likely to fall through the cracks (Schoen et al., 1997). The key reasons adolescents give for going without care are reluctance to let their parents know why they need care, cost, and lack of insurance. Some adolescents have access to care through school-based health centers, community-based centers, and other sources (Schoen et al., 1997). The benefits of providing care through these facilities were amply demonstrated in many of the presentations discussed below, but their numbers are few. For example, fewer than 1,400 school-based centers were counted in the 2001–2002 National Assembly on School-Based Health Care Census, almost half of which serve high school students (National Assembly on School-Based Health Care, no date) (more information on school-based health centers is provided in Chapter 4).6 Subsidized family planning services were provided in 7,682 sites in 2001; it has been estimated that 4.9 million adolescents need these services (Guttmacher Institute, 2005).

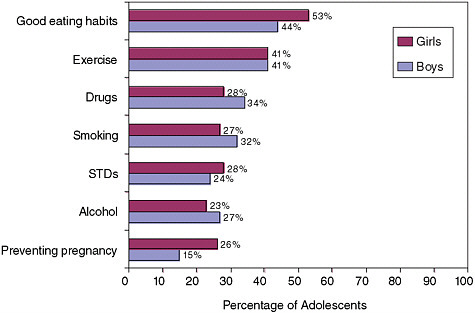

Care for adolescents falls short in some other ways, according to Charles Homer (National Initiative for Child Health Quality). The rate of medical errors (in diagnosis and treatment) is also higher for adolescents than for any other age group except (for some kinds of errors) newborns with medical conditions. Adolescents are more likely to receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics than are younger children and more likely to incur out-of-pocket expenses. Inadequate preventive care, however, is the most important problem Homer identified. He cited state-level data indicating that only about half of the encounters with providers create the opportunity for adolescents to have private or confidential visits or to ask about any critical risk behaviors (Shenkman, Youngblade, and Nackashi, 2003). Figure 2-2 shows the percentages of adolescents who report ever having discussed critical health risk topics with a health professional.

Moreover, despite the importance of well-child visits, the percentage of children receiving them declines from 84 percent for 5- to 10-year-olds to 66 percent for 15- to 17-year-olds (Yu et al., 2002). Adolescents also lag behind younger children in the rate at which they receive recommended immunizations and dental visits. Management of chronic medical and

FIGURE 2-2 Summary of topics health care providers have discussed with adolescents, as reported by adolescents in grades 5 through 12. Data from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls and Boys.

SOURCE: Ackard and Neumark-Sztainer (2001). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

mental health conditions and the transition to adult care are also insufficient, in Homer’s view. Adolescents are less likely to receive appropriate treatment to control asthma, for example, than younger children or adults (and all Medicaid recipients are less likely to than patients covered by commercial health plans). According to one study, just 20 percent of adolescents with chronic conditions have discussed with their doctors the ways their needs will change as they reach adulthood and shift to a provider who treats adults, and their plans for addressing these changing needs (Lotstein et al., 2005).

Views of Adolescents and Their Parents

When adolescents and their parents are asked about the care they receive, a similar divergence between recommended standards of care and reality is evident. The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative through the Young Adult Health Care Survey of the Oregon Health and Science University has developed standardized measures for a variety of issues related to the quality of health care for adolescents. Data presented by Christine Bethell (Oregon Health and Science Uni-

versity) shows, for example, that more than 40 percent of adolescents report receiving no counseling on any topics related to risky behaviors, unwanted pregnancy, or sexually transmitted diseases. Nearly 40 percent received no counseling on diet, weight, or exercise, and 41 percent received no counseling on depression, mental health, or relationships. Adolescents also say they lack opportunities for private and confidential visits with practitioners to discuss these subjects—just 25 percent in this study had a confidential visit related to risky behaviors. While the numbers are somewhat larger for other issues, only slightly over half (53 percent) reported usually or always having good communication with providers.

Even when they receive health counseling, adolescents do not always find it helpful: 83 percent of those who received counseling for birth control said it was helpful, 80 percent felt that way about HIV counseling, and the rates were 70 percent for counseling about drinking and 63 percent for smoking. The features adolescents say they look for in counseling, according to the survey, are clear explanations, shared decision making, respect, and trust.

Parents were asked a different set of questions and also reported significant dissatisfaction with the care they are able to get for their adolescents. Among parents of children and adolescents (ages 5–18), for example, fewer than half reported that their care met all the criteria for what was defined as a “medical home,” which included ready access to a provider, coordination of care, and other factors linked to high-quality primary care. The percentages declined from 48 percent for children ages 4 through 7 to just 39 percent for those ages 15 to 17, and they were lowest for black and Hispanic parents.

From Bethell’s perspective, care for adolescents could be improved on five critical elements of preventive care: regular visits, privacy and confidentiality, screening, counseling, and culturally sensitive partnerships with adolescents and their families.

Disparities in Health Status and Care

Indications of disparities in access to health status and quality of care among population subgroups were evident in almost every discussion. Anne Beal (The Commonwealth Fund) presented some of the data on this issue and also described some of the limitations to the available data. Her troubling finding is that minorities are at a disadvantage in most of the indicators she presented. Black and American Indian young men have the highest death rates—at 173 and 145 per 100,000 males ages 15 to 24, respectively. The rate for Hispanic males is 114 and that for whites is 107 (Center for Applied Research and Technical Assistance, no date). Hispanic

adolescents are more likely than those of any other group to lack health insurance—28 percent of them are uninsured compared with 12 percent of black and 8 percent of white adolescents (Newacheck et al., 2004). Hispanic young women also have the highest birth rates among adolescents, at 82 per 1,000 females ages 15 to 19, compared with 64 for blacks and 27 for whites (Martin et al., 2005). Blacks are the most likely to contract acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), with 3.4 per 100,000 adolescents ages 13 to 17 reported in 2003, compared with 0.7 for Hispanics and 0.1 for whites (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005).

While this evidence is compelling, Beal explained that measures of disparities in health care rely on quality measures that frequently are not adequate to characterize important differences. Methods for collecting data about the race and ethnicity of patients vary significantly, for example. Admitting clerks or providers may either ask the patient or record their own observations, or the patient may reply to a question on a form—and this inconsistency could significantly skew results. Moreover, while quality measures are in place for the care of children, relatively few are exclusive to adolescents, so the results of child health quality measures make it difficult or impossible to disentangle the relevance for a specific group—by distinguishing among the treatment of infants, children, and adolescents.

A related problem is that data about nonmedical issues, such as behavior and social contexts, and questions about access to health care are collected in separate ways and by separate groups. As a result, integrating data about these two sets of issues can be difficult, yet they are intimately linked in terms of their influence on adolescents’ health status and care. The relationship between clinical outcomes and nonmedical and access issues is clearly an important factor in disparities in care and outcomes, but making these connections is very difficult using current data collection structures.

Denise Dougherty (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) addressed another set of questions about the quality of care available to different adolescent populations. She reviewed the available research on the effectiveness, quality, and costs of health care provided in community-and school-based centers, whose patients are overwhelmingly members of vulnerable groups. Dougherty found the research base limited and described a number of issues for future researchers to consider. Looking just at work that addressed programs that both delivered traditional health care (rather than categorical services, such as STD screening or family planning, exclusively) and served adolescents, she found relatively few studies. Moreover, those studies varied in their use of terms, methodological rigor, and the populations, settings, and topics studied.

From this evidence, Dougherty concluded that school-based health

centers appear to meet a need for services, although the evidence was less clear for neighborhood centers; that health outcomes were mostly favorable to the extent that data were available; and that the overall quality of centers could best be described as mixed.7 However, limitations of this body of research did not support any meaningful comparisons with other means of delivering care to vulnerable populations. She highlighted the importance of research that would

-

address the issues for which adolescents are most likely to need care;

-

address adolescents’ experiences and satisfaction with the care they receive in these settings;

-

identify the effects of the programs on individuals, communities, schools, etc.;

-

consider cost-effectiveness; and

-

evaluate different models for serving vulnerable groups.

Distinct Needs of Adolescents

Robert Blum presented another perspective on caring for adolescents. Building on the point that social and behavioral issues are the causes for the majority of adolescents’ health problems, he noted that these issues are often least well addressed by those providing care to young people. Adolescents need care that bridges the space between pediatrics and adult internal medicine and that addresses the nonmedical factors that affect their health.8 Adolescents, especially those with chronic or ongoing health problems, are not likely to receive guidance about making the transition to adult care and are not receiving care that adequately addresses behavioral issues. He acknowledged that although the benefits of this kind of guidance have received little research attention, they have been empirically demonstrated for certain health categories, such as STDs, HIV, and family planning care (Ozer et al., 2005). Moreover, broader benefits for more comprehensive care are likely to include promoting psychosocial and family well-being, addressing medical concerns, and teaching self-advocacy skills.

Richard Catalano (University of Washington) also addressed the social and behavioral factors that influence adolescent health, but focused on

mechanisms for affecting adolescents’ health outcomes other than visits to physicians’ offices and health centers. Catalano described the risk factors for adolescent behavior problems (see Box 2-1).

He also described key individual protective factors (high intelligence, resilient temperament, and competencies and skills) as well as social protective factors (prosocial opportunities, reinforcement for prosocial involvement, bonding (such as with a caring parent or other adult), and healthy beliefs and clear standards for behavior set by parents or guardians. Catalano traced the association of both risk and protective factors with a variety of the behaviors and circumstances that have a significant impact on health for good or ill: alcohol or illicit drug use, mental and

|

BOX 2-1 Risk Factors for Adolescent Behavior Problems Community Risk Factors

Family Risk Factors

School Risk Factors

Individual/Peer Risk Factors

SOURCE: Presentation by Richard Catalano, January 22, 2007. |

social problems, degree of academic success, and involvement with violence. He has concluded that although both risk and protective factors are linked to diverse health and behavior problems in ways that are predictable and consistent across population groups, contextual factors influence their effects on the health and behavior problems of adolescents. That is, risk factors are not evenly distributed within geographic areas, and the profile of risk, protection, and outcomes for the adolescents of a particular neighborhood should determine the strategies and interventions that are available to the adolescents who live there.

Catalano noted a number of widely used strategies that have not been demonstrated to be effective in preventing certain risk behaviors. These include peer counseling, mediation, and positive peer culture; nonpromotion to succeeding grades; after-school activities with limited supervision and programming; drug information, fear arousal, and moral appeal; the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program or DARE; gun buyback programs; firearm training; mandatory gun ownership; shifting peer group norms of gangs; and neighborhood watch.

He contrasted these interventions with others that have shown effectiveness in prevention of certain risky behaviors. The latter include

-

Prenatal and infancy programs

-

Early childhood education

-

Parent training

-

After-school recreation

-

Mentoring with contingent reinforcement

-

Adolescent employment with education

-

Organizational change in schools

-

Classroom organization, management, and instructional strategies

-

School behavior management strategies

-

Classroom curricula designed to promote social competence

-

Community and school policies

In addition to programs and interventions for adolescents, several programs that make use of strategies that have been evaluated and have demonstrated effectiveness for parent training include

-

Guiding Good Choices® (Spoth, Redmond, and Shin, 1998)

-

Adolescent Transitions Program (Andrews, Soberman, and Dishion, 1995; Dishion and Andrews, 1995)

-

Staying Connected with Your Teen® (Haggerty et al., 2006)

-

Creating Lasting Connections (Johnson et al., 1996)

-

Strengthening Families Program 10–14 (Spoth, Redmond, and Shin, 1998)

Catalano expressed concern that programs that either do not work or have not been evaluated are in wider use than those that have been shown to be effective. He also pointed out the challenges of using prevention strategies carefully, the most significant of which is to match the strategy to the specific risks that need to be addressed. Not only do the risk and protective factors in the community need to be accurately assessed, he explained, but the community’s resources and its readiness to take an active part in a strategy to protect its youth must also be considered. Moreover, even successful interventions do not bear fruit overnight— measurable results in the form of behavioral changes may not be evident for two to five years, and significant improvements in population health measures would lag well behind those changes.

LOOKING SYSTEMWIDE

Claire Brindis (University of California, San Francisco) challenged workshop participants to consider what a truly effective system of care for adolescents might look like, given what is known about their health profile, the ways they use care, and the unique attributes of this developmental stage. In making the argument that a far greater investment in adolescent health is needed, she pointed to four key points about health care for adolescents:

-

Preventable risky behaviors have a big impact on the health of adolescents.

-

There are significant gender and racial differences in adolescent health problems and risk factors and in the care needed by special populations.

-

There are four major developmental stages within the age span— early (10–14), middle (15–17), and late (18–19) adolescence, and early adulthood (20–24)—each of which presents distinct issues.

-

The transitions from middle childhood to adolescence and from adolescence to adulthood merit special attention from the health care system.

The cost to individuals, families, and communities of inadequate and inappropriate care may be difficult to measure, but without a doubt the economic cost is high. Considering only the direct and long-term social costs associated with six of the most common health issues adolescents experience (pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, motor vehicle injuries, alcohol and drug problems, other unintentional injuries, and mental health problems), at least $700 billion is spent annually in the United States on preventable adolescent problems (Hedberg, Bracken, and Stashwick, 1999).

Brindis argued that an improved approach to preventing these health problems should begin with understanding the way risky behaviors are clustered and shaping programs and policies for each. She identified four broad categories of adolescents whose needs are distinct: demographic subgroups; legally defined groups, such as incarcerated adolescents and adolescents in foster care; adolescents with chronic physical or emotional conditions; and adolescents in other circumstances that magnify their need, such as those who are pregnant or parenting or those who are homeless. The need is growing. Demographic groups that are generally less well served by the health care system are growing as the U.S. population becomes increasingly diverse. At the same time, the U.S. health care system is in a state of growing crisis, as rising prices and other factors put coverage out of reach for increasing numbers of families. Low-income adolescents already report poorer health status, less continuity of care, and more challenges in obtaining care than other groups.

While the circumstances and challenges facing these broad categories of adolescents vary, several factors hold true across the groups. When social and behavioral patterns are causing health problems, they are likely to cause multiple problems. Current medical practice tends to focus on individual health problems and to assign them to different practitioners, but a variety of issues may be interrelated and have a common etiology. A segmented approach may fit the needs of providers’ skills but lack the capacity to address the needs of adolescents with multiple health problems. An approach to care that takes into account the effects of the contexts in which adolescents live is likely, Brindis argued, to be more effective than the current approach to prevention, which tends to focus on isolated problems in individuals and families, one at a time.

Moreover, the positive youth development model, through which resiliency and protective factors are fostered, is likely to be more effective at promoting healthy development in adolescents than a deficit model focused on the challenges and problems common in this phase of life. Brindis offered a list of protective factors similar to the one offered by Catalano, including caring relationships, high expectations, and opportunities to participate and contribute, as well as traits that make adolescents resilient, including social competence, problem-solving skills, autonomy and a positive sense of self, and a sense of purpose and anticipation of a positive future.

Brindis sees training for providers who treat adolescents as the best way to create a broad-based prevention strategy for adolescent care that builds on protective factors and targets risk factors. Currently, she pointed out, just 25 of the 213 accredited pediatric residency training programs in the United States have fellowship programs in adolescent medicine that are approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Educa-

tion, and of those 25, only 7 include interdisciplinary training.9 Both physicians in training who expect to treat adolescents and nurses in practices that serve adolescents have been surveyed and report that they feel inadequately prepared to address the needs of this group of patients.

Both the Society for Adolescent Medicine and the American Academy of Pediatrics have both offered lists of key elements of high-quality care for this age group that include reproductive and mental health coverage, consent and confidentiality, trained and experienced providers, and coordination of care. Brindis closed her remarks with her view of the essential elements of a health care system that serves adolescents well:

-

Adolescents have access to a comprehensive system that provides necessary specialty care and coordination of care.

-

The system is adequately financed.

-

Adolescents have the skills to negotiate the system.

-

Preventable problems are prevented.

-

Chronic conditions are effectively managed and the transition to adult care is ensured.

David Grossman (Group Health Permanente) took another tack in considering the question of what adolescent care ought to look like. He argued that distinctions between managed care and other systems for delivering care are less useful than distinctions among systems that are or are not well organized to provide coordinated care. From his perspective, there is extensive variation among managed care plans, in terms of how well they coordinate care and provide access to specialty care, as well as other important indicators of quality. Thus, he prefers to focus on the necessary characteristics of care models that provide integrated care, rather than on the ways in which they are internally structured or financed.

Two models illustrate Grossman’s conceptual approach. The medical home model, originally developed as a way to ensure coordination in care for pediatric patients, focuses on collaboration with families to facilitate access to both primary and specialized care and develop continuous relationships with a personal physician (Sia et al., 2004). An overlapping concept is the chronic care model, which focuses on proactive, planned care that makes use of information technology to improve coordination between primary and specialty care and helps patients manage their own

care. Both models draw on community resources as well as health care systems to create productive relationships between informed patients and proactive providers that yield improved outcomes.

Some research indicates that these models can improve continuity of care, patient satisfaction, access to care and outcomes, and other characteristics (see for example Hung et al., 2007). Grossman suggested that these models are likely to be very well suited to caring for adolescents, but he observed that research is needed to explore such questions as their effects on costs and outcomes for adolescents, the optimal design for an adolescent care model, and the best approaches for engaging adolescents in taking responsibility for their own health.

HEALTH INSURANCE

Finally, almost every presenter in both workshops raised issues related to health insurance and other coverage. Abigail English (Center for Adolescent Health and the Law) summarized the issues in the context of the needs of vulnerable adolescents. In 2005, 47 million people in the United States, or 16 percent of the population, were uninsured, and the numbers are increasing (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, and Lee, 2006). Moreover, the percentage of those covered who obtain their insurance through an employer declined, while the percentage who rely on publicly funded coverage increased. If stretches of less than a year without insurance were counted, the numbers would be even larger. Older adolescents (15–18) are more likely to be uninsured than younger ones (10–14) (Newacheck et al., 2004), and 30.6 percent of young adults (18–24) were uninsured in 2005 (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, and Lee, 2006). The uninsured of all ages are disproportionately Hispanic and black, and 40 percent of uninsured adolescents have a family income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level (Newacheck et al., 2004).

There are several reasons why older adolescents and young adults are particularly likely to be without coverage. In most states, Medicaid and SCHIP coverage ends at age 19, and employer-based coverage of dependents usually covers dependents over age 18 years only if they are full-time students. The cost of individual policies is often out of reach for this age group. Vulnerable groups, such as homeless and incarcerated adolescents, adolescents in foster care, and immigrant adolescents, are especially likely to lack coverage, even when they are eligible, because they tend to lack supports, are frequently unemployed, and do not have an ongoing connection to responsible adults.

Brindis cited data indicating specific weaknesses in insurance coverage. One analysis of private health insurance in 48 states found coverage of rehabilitation and mental or behavioral health care, including treatment

for substance abuse, was inadequate (Fox, McManus, and Reichman, 2003), while another study found that less than 10 percent of adolescents who abuse or depend on substances had received treatment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). Blum also addressed this point, noting that the current system for financing health care specifically precludes coverage for much of the care that is most needed. Insurance companies cannot shoulder this burden alone, Blum argued; a public-sector commitment is needed to take on an issue of this magnitude. English described options that have been proposed, such as MediKids,10 which would have expanded publicly funded coverage to age 23, as well as local initiatives that are filling some gaps. In her view, workable policy options exist, but advocacy, supported by research to document both the need for and the potential value of proposed solutions, is necessary to bolster the political will needed to put them to work.