G

The Jurisprudence of Privacy Law and the Need for Independent Oversight

Privacy protection rules regulating law enforcement and national security use of personal information can be usefully understood in two distinct categories: first, substantive rules that limit access to and usage of private information and, second, procedural rules that provide safeguards to encourage compliance and ensure accountability for compliance failures.

Neither the Constitution nor any statute can anticipate in advance every particular privacy issue raised by future technologies. So the evolving balance between the government’s need to intrude on the private lives of individuals in the service of its public safety mission and the requirement to maintain individual liberty has been maintained over time by providing a degree of transparency in the use of new technologies, along with accountability to rules assured by judicial and legislative oversight. As new technologies and investigative techniques come into use, courts and legislatures have the opportunity to review these advances and make assessments of their privacy impact, guided by constitutional and public policy foundations. When new privacy risks arise or when the government powers are judged to have been extended beyond the boundaries established through the democratic process, corrective action can be taken. In order for this dynamic equilibrium of privacy and public safety to be maintained, however, transparency of the investigative process and accountability to the rule of law are essential. This appendix presents both the substantive constitutional foundations of privacy rights necessary for evaluating new technology, along with a consideration of transparency,

accountability, and oversight mechanisms necessary to keep counterterrorism activities within view of the democratic process.

G.1

SUBSTANTIVE PRIVACY RULES

In general, substantive privacy rules involve restrictions on access to and use of personal information by the government. Such restrictions are a means of limiting the power of government and private-sector institutions. For example, in the spirit of the bedrock constitutional principle of limited government, the Fourth Amendment defines limits on government power by establishing individual rights against certain intrusions. It protects privacy not only because Americans value individual liberty as an end in and of itself, but also because their collective political, cultural, and social flourishing depends on it. To this end, privacy protections generally take the form of boundaries between individuals and institutions (or sometimes other individuals). These boundaries may limit the information that is collected (in the case of wiretapping or other types of surveillance), how that information is handled (the fair information practices that seek care and openness in the management of personal information described in Box G.1), or rules governing the ultimate use of information (such as prohibitions on the use of certain health information for making employment decisions).

Today, a variety of new technologies put pressure on existing boundaries between individuals and large institutions. New surveillance and analysis technologies used in the service of counterterrorism goals are effective precisely because they give investigators new capabilities that erode the boundaries previously established between individuals and governments. For example, data mining techniques operating over large collections of information, each element of which is not particularly revealing, may yield detailed profiles of individuals, and location-aware sensor networks allow collection of tracking information on large numbers of individuals when most of them are not actually suspected of any crime at the time of data collection. New identification documents (including driver’s licenses and passports) will collect biometric information in digital form on most of the population, marking the first time the digital images of the faces of the population will be available for law enforcement use. All of these technologies are susceptible to a wide variety of different uses, with widely varying intrusiveness.

G.1.1

Privacy Challenges Posed by Advanced Surveillance and Data Mining

Many of the privacy questions facing the information age society are

|

BOX G.1 Fair Information Practices Fair information practices are standards of practice required to ensure that entities that collect and use personal information provide adequate privacy protection for that information. These practices include notice to and awareness of individuals with personal information that such information is being collected, providing them with choices about how their personal information may be used, enabling them to review the data collected about them in a timely and inexpensive way and to contest that data’s accuracy and completeness, taking steps to ensure that their personal information is accurate and secure, and providing them with mechanisms for redress if these principles are violated. Fair information practices were first articulated in a comprehensive manner in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s 1973 report Records, Computers and the Rights of Citizens.1 This report was the first to introduce the Code of Fair Information Practices, which has proven influential in subsequent years in shaping the information practices of numerous private and governmental institutions and is still well accepted as the gold standard for privacy protection.2 From their origin in 1973, fair information practices “became the dominant U.S. approach to information privacy protection for the next three decades.”3 Their five principles not only became the common thread running through various bits of sectoral regulation developed in the United States, but also they were reproduced, with significant extension, in the guidelines developed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These principles are extended in the OECD guidelines, which govern “the protection of privacy and transborder flows of personal data” and include eight principles that have come to be understood as “minimum standards … fortheprotection of privacy and individual liberties.”4 The OECD guidelines also include a statement about the degree to which data controllers should be accountable for their actions. This generally means that there are costs associated with the failure of a data manager to enable the realization of these principles.

|

|

As enunciated by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (other formulations of fair information practices also exist),5 the five principles of fair information practice include:

SOURCE: National Research Council, Engaging Privacy and Information Technology in an Information Age, J. Waldo, H.S. Lin, and L. Millett, eds., The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2007. |

both challenging as a matter of public policy and difficult because they seem to call into question the adequacy of much of existing privacy law. A strong constitutional foundation constrains government actions and policies: the Fourth Amendment guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure. Although the U.S. Supreme Court has rejected the idea that the Fourth Amendment protects a general right to privacy, the amendment does create boundaries between the citizen and the powers of the state in certain domains. In the words of the Court,1

[T]he Fourth Amendment cannot be translated into a general constitutional “right to privacy.” That Amendment protects individual privacy against certain kinds of governmental intrusion, but its protections go further, and often have nothing to do with privacy at all. Other provisions of the Constitution protect personal privacy from other forms of governmental invasion. But the protection of a person’s general right to privacy—his right to be let alone by other people—is, like the protection of his property and of his very life, left largely to the law of the individual States.

Yet the Court’s interpretation of what types of intrusions raise constitutional questions has been flexible over time, reflecting the underlying values of the Fourth Amendment. In Katz and subsequent cases, the Court rejected the idea that rights conferred by the Fourth Amendment are determined by fixed physical or technical boundaries. As the Court explained:

[T]he Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection. See Lewis v. United States, 385 U.S. 206, 210; United States v. Lee, 274 U.S. 559, 563. But what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected.

The actual boundaries of the Fourth Amendment have changed over time, shaped by changing technological capabilities, social attitudes, government activities, and Supreme Court justices, as indicated by a series of Supreme Court decisions in the past century. The nature of this evolution, driven both by judicial intervention and legislative action, demonstrates an ongoing and vital role for policy makers and jurists to ensure that the values reflected in the Fourth Amendment are kept alive in the face of new technologies.

Whether a government activity is permissible under the Fourth Amendment is determined by the answer to two basic questions: (1) is the action a “search” within the meaning of the Constitution and (2) if it is a

search, is it “reasonable.” A government action is considered a search if it crosses into some recognized private interest. What constitutes a private domain is sometimes easy to determine based on history and culture, the canonical one being a person’s private home. But a dependence on history implies that there is no fixed definition of “private domain,” and thus it falls to statutory law, judicial action, and executive branch action to protect privacy within whatever definition of private domain has been defined at the time.

As an example of how constitutional jurisprudence and statutory law have interacted to strike a balance between the protection of privacy and the legitimate needs of law enforcement, consider the legal framework surrounding telephone wiretaps. This framework requires communications carriers to provide law enforcement agencies (LEA) with lawful intercepts (LI) (e.g., wiretaps) on specific telephones under specific conditions once the appropriate warrants or subpoenas have been issued and presented. LI laws require that wiretaps be very specific—for an ongoing investigation, for a specific subject (individual), and often for a specific form of communications, such as a wire-line telephone and for a specific telephone number.

While some may have an image of a detective sitting in a smoky hotel room listening to a call via a wire tapped to a phone in an adjacent room, modern LI or electronic eavesdropping is automated as an integral part of the telecommunications infrastructure. When a law enforcement agency provides a communications carrier with a warrant for a specific lawful intercept, the communications carrier is obligated to intercept the content of specific communications and deliver them to the agency. Typically, this involves routing calls to a location designated by the law enforcement agency, where the information is captured and stored for later analysis using technologies designed for communications surveillance and analysis.

The first step in establishing today’s legal framework was the Katz decision of the Supreme Court in 1967. In that decision, the Court found that a person in a telephone booth had a reasonable expectation of privacy and thus the content of phone conversations in the booth was entitled to the protections of the Fourth Amendment. In response to this decision, Congress passed the 1968 Wiretap Act (now known as Title III).

Strictly speaking, Katz v. United States addressed only the issue of whether the Fourth Amendment applied to telephone conversations held in a public telephone booth.2 But the Wiretap Act imposed requirements on law enforcement officials to obtain warrants for wiretaps on conversa-

tions regardless of where they were being held, and it laid out a variety of conditions that had to be met for a warrant to be issued—conditions that were not stipulated in the Katz decision.

Since the Wiretap Act was passed, Congress has enacted many laws governing lawful intercepts, including the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (CALEA), the Pen Register/Trap and Trace Provisions of Title 18; and the Interception and Pen/Trap provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, Title 50 U.S.C. Sections 1801-1845 (FISA). These laws have a historical context that reflects technology prevalent when the laws were written, and they were sometimes passed in response to a new Supreme Court decision or public demands for greater privacy acted on by the legislature.

G.1.2

Evolution of Regulation of New Technologies

New technologies often pose challenges for courts and policy makers in deciding whether the surveillance power made available constitutes a permissible intrusion on a private interest.

Table G.1 illustrates the ways in which the law of electronic surveillance has evolved privacy protections over time. For example, early wiretapping was found not to violate the Fourth Amendment in 1928, but when the Supreme Court considered the question of telephone surveillance again in 1967, it reversed itself and found that citizens’ reasonable expectation of privacy in private telephone calls meant that surveillance of telephone calls could be done only with a judicially approved warrant and ongoing supervision of a “detached, neutral magistrate.” As reliance on new communications technologies continued, Congress stepped in to establish basic privacy protections and provisions for law enforcement access to electronic mail. In an important instance of proactive legislative action determined to be necessary to provide stable privacy protection for a new electronic communications medium, Congress acted on the belief that “the law must advance with the technology to ensure the continued vitality of the Fourth Amendment.”3

With the advent of the World Wide Web, congressional action extended privacy protections to web and e-mail access transaction logs, along with clear procedures for legitimate law enforcement access with judicial supervision.

A more recent consideration of a new technology—use of infrared scanning of a person’s home for the purpose of detecting high-heat plant grow lights (indicating a possible indoor marijuana farm)—was found to

TABLE G.1 Historical Evolution of Regulation of Electronic Surveillance

|

|

Communications Technology |

Law |

Regulatory Approach |

|

1890s |

Telegraph |

State wiretapping crimes |

Criminal prohibition |

|

1934 |

Telephone |

Communications Act of 1934 |

Criminal prohibition and inadmissibility of evidence |

|

1967 |

Telephone and bugging equipment |

Fourth Amendment |

Inadmissibility of evidence and civil liability |

|

1968 |

Telephone and bugging equipment |

Wiretap Act |

Criminal prohibition, civil liability, and inadmissibility |

|

1978 |

Telephone and bugging equipment |

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act |

Criminal prohibition, civil liability, and inadmissibility |

|

1986 |

E-mail and Internet communications |

Electronic Communications Privacy Act |

Criminal prohibition and civil liability |

|

2001 |

Telephone and Internet |

USA Patriot Act |

Criminal prohibition and civil liability |

be a violation of the Fourth Amendment. Justice Antonin Scalia found4 that this transgressed the inviolability of the home, even though the police officers using the infrared detector did not actually enter the person’s home.

Still another issue arising recently is the changing relevance of political boundaries to communications. Previous communications technologies and the laws that addressed them often reflected political boundaries. In today’s communications technologies, political boundaries may be impossible to determine. This is significant, since a significant portion of the world’s communications traffic is routed through U.S. switches, raising questions on the propriety of electronic eavesdropping on communications whose origins and destinations cannot be determined. In this case, recent legislation addresses this point,5 allowing the warrant-

less monitoring of communications that pass through the United States as long as both parties to the communications are reasonably believed to be located outside it.

As the above examples illustrate, the regulation of new technologies is affected by both by the evolution of the Supreme Court’s Fourth Amendment jurisprudence on what constitutes a search and by policy choices within those boundaries made by the legislative and executive branches. Supreme Court jurisprudence on this point has evolved to limit government intrusion into certain “protected areas” because the founding fathers could not have anticipated the current and forthcoming advances in technology and practices. Furthermore, legislative and executive branch policy makers have expanded the scope of protections to ensure that constitutional values of limited government and protection of individual liberty are protected notwithstanding technological advances.

Legal analysts have a variety of views on whether regulation of new technologies should be driven by policy decisions or by the Fourth Amendment. For example, one view is that legislatures have considerable institutional advantages that enable the legislative privacy rules regulating new technologies to be more balanced, comprehensive, and effective than judicially created rules, and that the courts should adopt only modest formulations of Fourth Amendment protections in deference to these advantages.6 Another view is that constitutionally derived protections of privacy in the face of new technologies are, by definition, more enduring and thus less subject to the often poorly justified actions of legislatures and executives, who may be acting in the heat of the moment after a terrorist incident.7 Of course, in practice, regulation of new technologies has been influenced by both policy decisions and the Fourth Amendment.

It would be a mistake to infer from this brief history that every new surveillance technology is greeted automatically by courts and legislatures with a fixed, linear expansion of privacy protection. In some cases, long periods of time go by before a given technology receives clear privacy consideration. And it is certainly not possible to establish a priori clear measures of how much privacy protection ought to be brought to bear on new surveillance capabilities. What this history reveals is that careful consideration of the privacy impact of new surveillance powers has generally resulted in a measure of privacy protection that gives citizens confidence, while at the same time preserving apparently adequate

access to data for law enforcement engaged in legitimate investigative activity.

G.1.3

New Surveillance Techniques That Raise Privacy Questions Unaddressed by Constitutional or Statutory Privacy Rules

A number of the government counterterrorism investigative techniques with real privacy implications are likely to fall outside the boundary of what the Supreme Court today considers to be a search. Inasmuch as all levels of government are now seeking to use the most advanced, effective technologies to detect and apprehend terrorist threats, it is not surprising that many of these new technologies and techniques will have intrusive power not previously considered by either courts or legislators. The committee heard considerable testimony on the use of data mining for the purpose of identifying potential terrorist behavior. In many cases, the bulk of the information used in such data mining operations is collected from commercial data vendors and public records, such as property records, voting rolls, and other local and state databases. Access to these data is available with little or no privacy protection and little or no third-party supervision.8 Furthermore, while data mining activity may be subject to procedural regulation under the federal Privacy Act (see Appendix F), it is not subject to any substantive statutory limitations whatsoever. It will be up to Congress to consider the appropriate limits on the use of data mining and other new privacy-invasive techniques.

G.1.4

New Approaches to Privacy Protection: Collection Limitation Versus Use Limitation

There is growing agreement that regulation of large-scale analysis of personal information, such as data mining, will have to rely on usage limitations rather than merely collection limitations.9 Historically, privacy

|

8 |

See Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979) (finding no reasonable expectation of privacy transactional records of phone numbers dialed because they were “disclosed” voluntarily and duly recorded by the phone company in the ordinary course of business); and United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435 (1976) (finding no Fourth Amendment interest in banking records, since they are not confidential communications and are voluntarily presented to the bank). See also J.X. Dempsey and L.M. Flint, “Commercial data and national security,” George Washington Law Review 72(6):6, August 2004. |

|

9 |

See the reports from the Markle Foundation Task Force on National Security in the Information Age: Mobilizing Information to Prevent Terrorism: Accelerating Development of a Trusted Information Sharing Environment, 3rd Report, July 13, 2006; Creating a Trusted Network for Homeland Security, 2nd Report, December 2, 2003; and Protecting America’s Freedom in the Information Age, 1st Report, October 7, 2002. Available at http://www.markletaskforce.org/ [11/7/07]. |

against government intrusion has been protected by limiting what information the government can collect: voice conversations collected through wiretapping, e-mail collected through legally authorized access to stored data, etc. But today, as the data mining discussion in Appendix H illustrates, the greatest potential for privacy intrusion may come from analysis of data that are accessible to government investigators with little or no restriction and little or no oversight. The result is that powerful investigative techniques with significant privacy impact proceed in full compliance with existing law, but with significant unanswered privacy questions and associated concerns about data quality. However, attempts to limit collection of or access to the data that feed data mining activities may create significant burdens on legitimate investigative activity without producing any real privacy benefit. In many cases, the data in question have already been collected and access to them, under the third-party business records doctrine, will be readily granted with few strings attached.

The privacy impact of new analytic techniques that merit regulation is not access to any individual element of personal information, but rather to the overall use of a large quantity of individually innocuous items of personal information. As the debate over airline passenger screening systems has shown,10 the main objections to proposed profiling systems are in the potential for “mission creep” and the risk of inaccurate data being used against innocent citizens.

The challenge before policy makers is how to craft appropriate privacy regulation that achieves the historic but dynamic balance between privacy protection and important public safety priorities. Establishing clear usage limitations along with traditional procedural oversight safeguards on new data analysis techniques—including but not limited to data mining—would ensure that the most powerful new investigative techniques are available against the serious threats to national security. At the same time, given the substantial new and untested power that these techniques could confer on domestic law enforcement, their use in the nonnational security arena would be limited.

G.2

PROCEDURAL PRIVACY RULES AND THE NEED FOR OVERSIGHT

The establishment of law and regulation in any given domain is an articulation of public concerns and values in that domain. But if law and

|

10 |

See Department of Homeland Security, Notice to Establish System of Records, Secure Flight Test Records, 69 Fed. Reg. 57,345 (Sept. 24, 2004), available at http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2004/04-21479.htm, and comments (link to criticism publications available at http://www.epic.org/privacy/airtravel/secureflight.html). |

regulation are to have any substantive or tangible impact on behavior, mechanisms are necessary for ensuring that the targets of such law and regulation behave accordingly.

In the context of the Fourth Amendment, such mechanisms are provided through third-party review of government intrusions on private domains. When properly implemented, such mechanisms provide a significant measure of accountability to ensure that these intrusions are not abused.

G.2.1

Oversight Mechanisms of the U.S. Government

The U.S. government is based on a three-way system of internal checks and balances that was designed to limit power and ensure reviews across the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. For example, the president nominates Supreme Court and Circuit and District Court judges and the Congress votes to confirm them. The president also proposes budgets, which Congress must approve. For national security issues, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) conducts investigations inside the United States that are subject to oversight by the Federal Intelligence Security Court (established by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act).11 In addition, Congress oversees the activities of the Department of Justice, which is responsible for the FBI.12

Congressional oversight of executive branch departments and agencies are especially potent and controversial because congressional committees have the power of subpoena and they control budget allocations. In addition, congressional committee meetings generate intense press and public interest, especially when they are investigating failures, corruption, or other malfeasance. This form of oversight, called “fighting fires,” is contrasted with scheduled regular reviews, called “patrolling streets.”13

Some politicians are attracted to fighting fires because of the high visibility, but the patrolling streets model can be successful in preventing

|

11 |

J. Berman and L. Flint, “Guiding lights: Intelligence oversight and control for the challenge of terrorism,” Criminal Justice Ethics, Winter/Spring 2003. Available at http://www.cdt.org/publications/030300guidinglights.pdf [11/7/07]. |

|

12 |

C.J. Bennett and C.D. Raab, The Governance of Privacy: Policy Instruments in Global Perspective. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2006. |

|

13 |

M.D. McCubbins and T. Schwartz, “Congressional oversight overlooked: police patrols versus fire alarms,” American Journal of Political Science 28(1):165-179, February 1984; A. Lupia and M.D. McCubbins, “Designing bureaucratic accountability,” Law and Contemporary Problems 57(1):91-126, 1994; A. Lupia and M.D. McCubbins, “Learning from oversight: Fire alarms and police patrols reconstructed,” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 10(1):96-125, 1994; and H. Hopenhayn and S. Lohmann, “Fire-alarm signals and the political oversight of regulatory agencies,” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 12(1):196-213, 1996. |

problems, although it takes more effort. Critics of congressional oversight suggest that at times members may not be sufficiently informed to ask the right questions or appreciate the complexities of the agencies they review.

Executive branch agencies often create independent oversight boards to review internal activities so as to improve performance and generate public trust. Examples include the National Aeronautic and Space Administration’s Shuttle Oversight Board,14 the Department of Energy’s Performance Assurance Program Independent Oversight,15 the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Drug Safety Board,16 and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Oversight Committee.17 In addition, agencies often have internal oversight committees and inspectors general who monitor compliance with policy.

The judicial branch is often the arbiter of government claims that invasions of individual privacy are needed to advance other national interests. For example, warrants that allow physical searches and orders that allow wiretapping are often issued by the judicial branch upon the showing of probable cause. In this way, the courts handle many cases of potential privacy violations by federal, state, and local police or other government agencies.

Federal agencies also conduct oversight of parts of the commercial sector to ensure adherence to legal requirements and consumer protection. Examples include the Federal Reserve’s regulation of banking practices and the FDA’s work on pharmaceutical testing and production. Government agencies can also be the source of trusted investigations, such as the work of the National Transportation Safety Board in studying plane crashes.

Other mechanisms to detect problems in government and other organizations are sometimes applied. Some organizations include ombudsmen whose role is to constantly review practices and respond to internal or external concerns. Another strategy that has legal protection in U.S. is whistle-blowing. Government employees who report illegal or improper

|

14 |

See NASA, Standing Review Board Handbook, August 1, 2007; available at http://fpd.gsfc.nasa.gov/NPR71205D/SRB_Handbook.pdf. |

|

15 |

See U.S. Department of Energy, Independent Oversight and Performance Assurance Program, DOE O 470.2B, October 31, 2002; available at http://hss.energy.gov/IndepOversight/guidedocs/o4702b/470-2b.html. |

|

16 |

See information on the Food and Drug Administration’s Drug Safety Oversight Board at U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Improvements in Drug Safety Monitoring,” FDA Fact Sheet, February 15, 2005; available at http://www.fda.gov/oc/factsheets/drugsafety.html. |

|

17 |

U.S. Senate, Committee on Environment and Public Works, Subcommittee on Clean Air and Nuclear Safety. |

activity are protected by several laws, especially the Whistleblower Protection Act (5 U.S.C. § 1221(e)).

These mechanisms for oversight vary in the extent to which they are (and are perceived to be) independent. Independence (along with the necessary authority) is a key dimension of oversight because of the suspicion—often warranted—that oversight controlled or influenced by the entity being overseen is not meaningful and that problems revealed by nonindependent oversight will be concealed or improperly minimized. Independent oversight mechanisms also generally have greater ability to bring fresh and unbiased perspectives to an organization that is caught up in its day-to-day work.

G.2.2

A Framework for Independent Oversight

The rich variety of independent oversight strategies makes it difficult to compare them and recognize missing features. A framework for understanding the organizational structures and operating methods would therefore help identify best practices and sources of successful outcomes. Some clarity can be gained by taking a “who, when, how, what” approach, as described by these components:

Who: Ensure independence.

When: Choose time for review.

How: Set power to investigate.

What: Raise impact of results.

Administrators will need to tune the process to fit each situation, but these components can serve as a starting point. First, some definitions: the independent oversight board members are referred to as members, and their goal is to review the operation of an organization led by administrators who supervise employees.

Ensure Independence

Attaining the right level of independence means that the independent oversight board members are distant enough from the organization and employees so that their judgments are free from personal sympathy, coercion, bias, or conflicts of interest. However, they need to be close enough to be familiar with the organization and its operation. Members need to be knowledgeable about the domain of work and experienced at doing reviews of other organizations. In corporate audits, the independent accounting firms have helpful expertise in that they review multiple corporations, so they are familiar with standard and risky practices in

each industry. Many analysts believe that the fraudulent business practices that led to the collapse of Enron could have been flagged by its accounting firm, Arthur Anderson, but they failed to do so because of their lack of independence.

Independent oversight board members should be trusted individuals whose credibility is also respected because of their career accomplishments. In addition to distance, experience, trust, and credibility, another issue tied to independence is transparency. While some activities may need to be kept private, the process should be visible enough.

Match Nature of Review to Appropriate Stage in Event Trajectory

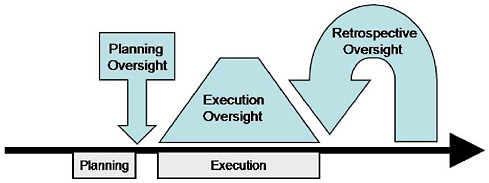

Oversight typically occurs at three points: before, during, and after some activity. These forms of oversight can be regarded as relevant to planning (approval of a proposed activity), execution (monitoring of activity while it is happening), and retrospective review (review of a completed activity) (see Figure G.1.)

-

Planning oversight occurs when a specific activity has been planned but before any work begins. For example, the FISA court reviews approximately 2,000 plans for surveillance by the FBI each year; rejections are extremely rare. Another government example is the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, which reviews Department of Defense decisions. Academic examples include the approval of plans for medical experiments by institutional review boards. Planning oversight also includes review boards that are convened to help make critical decisions, such as the launch of National Aeronautics and Space Administration missions, the opening of natural preserves to oil drilling, or acceptance of papers for publication in scientific journals.

FIGURE G.1 Planning oversight is a check on plans, execution oversight is continuous review, and retrospective oversight reviews past performance.

-

Execution oversight is the continuous oversight (patrolling streets) of a process, such as meat packing, pharmaceutical manufacture, or banking. Such processes can be labor-intensive and boring but require continuous vigilance. Independence is a challenge in these circumstances, since the oversight members may work closely with employees on a daily basis, thereby becoming personally familiar with them. The Federal Reserve Board has strict rules about personal contacts of its regulators with bank employees.

-

Retrospective oversight occurs when the review covers previous organizational operations (fighting fires is one form) to validate performance and provide guidance for future performance. Corporate audits by independent accountants typically review a fiscal year and produce a report within 30-90 days. Audit reports must be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and become public. University tenure committees are retrospective reviews, in that the members review career accomplishments of junior academics. University accreditation committees typically deal with retrospective as well as planning oversight; for example, they may review the past five years and plans for the next five years. In the U.S. government, the inspector general is an internal reviewer but sometimes functions to review other agencies or departments.

Provide Authority to Investigate

Independent oversight boards typically receive written reports and live presentations, but in many cases they can ask questions of individuals or request further information. In some cases, they have subpoena power to require delivery of further information. A greater power to investigate raises the importance of an oversight committee and increases its perceived independence. The time limits on an independent oversight also influence its efficacy. A short review of a day or two for a review may not be enough to uncover problems, while long reviews can be a burden on organizations.

The forms of investigation vary widely, from simply reading of internal reports to extensive interviews with administrators and employees. Deeper investigations could assess organizational impact on others, such as customers, travelers, visa applicants, etc., by personal interview, survey questionnaire, or data collection (e.g., monitoring water quality).

Disseminate Results of Oversight

Independent oversight boards typically produce a printed report, and its distribution is critical to its impact. If the only recipients are the

administrators being reviewed, then there is a chance that the report will be ignored. If the recipients include employees, other stakeholders, journalists, and wider circles of the interested public, then the impact could be greater.

Independent oversight boards may also present their results verbally in private or public forums to the employees and administrators being reviewed. Some discussion may be allowed, and revised reports may be made. Such presentations can help ensure that the report is well understood and that appropriate clarifications are made, and recommendations for change contained in such reports are more likely to be implemented if they are made public.

Reports can also be made public and permanently available, as in SEC filings. A further possibility is that reports may include timetables for implementing changes and a review process to ensure that recommendations are followed.

Since there may be disagreements among independent oversight board members, a minority report may be included to allow strongly felt concerns to be raised by a subset of the members. Such minority reports, as in Supreme Court decisions, allow public exposure of alternate views that may be useful in future discussions.

G.2.3

Applying Independent Oversight for Government Agencies to Protect Privacy

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has a difficult job that includes ensuring transportation safety, protecting national infrastructure, investigating terror threats, and many other tasks. For these and other purposes, DHS conducts extensive surveillance, which may invade the privacy of U.S. residents. DHS makes several efforts to assess its performance and provide internal and independent oversight. By statute, DHS has a chief privacy officer (Hugo Teufell III, appointed in July 2006), a Privacy Office, and a 20-member Data Privacy and Integrity Advisory Board (http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/structure/editorial_0510.shtm). The mission statement of the DHS Privacy Office is “to minimize the impact on the individual’s privacy, particularly the individual’s personal information and dignity.” It remains to be seen whether the advisory board acts more as an internal review committee or a truly independent oversight board.18

Within DHS, the Citizenship and Immigration Services has an

|

18 |

M. Rotenberg. The Sui Generis Privacy Agency: How the United States Institutionalized Privacy Oversight After 9-11, September 2006. Available at http://epic.org/epic/ssrn-id933690.pdf. |

ombudsman office to help individuals and employers in resolving problems. They make an annual report to Congress and submit recommendations for internal improvements.

Other agencies, such as the FBI (in the Department of Justice) must request review of planned investigations by the FISA court, but they have rarely been turned down.19 There does not seem to have been a retrospective review mechanism for the FISA court, or a retrospective review by the FISA court of FBI performance.

The president’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (http://privacyboard.gov/) held its first meeting with six members in March 2006. This board could be helpful in generating public trust, but concerns about its independence and efficacy were raised after its first public presentation in December 2006. If this board can promote planning, execution, and retrospective oversight, it could emerge as a positive influence on many government agencies.

Public concern about warrantless domestic surveillance has become a controversial topic. A federal judge in Michigan found in July 2006 that government surveillance required review by a FISA court. After fighting this decision, the current administration agreed to FISA court oversight for at least some of their intelligence operations, but as this report is being written, the ultimate outcome of the relevant legislative proposals is unclear.

The traditional reliance on judicial review for privacy protection remains an effective process for dealing with evolving technologies and normative expectations. The judiciary’s role in protecting the legal and privacy rights of citizens is effective because judicial decisions are a form of independent oversight that is widely respected. Furthermore, the rights it protects are established by the Constitution, which all branches of government are sworn to uphold.

Independent oversight is potentially very helpful for continuous improvement of government operations, especially when dealing with the complex issues of privacy protection. There are many forms of independent oversight and many strategies for carrying it out. Some government agencies conduct responsible independent oversight programs, but critics question their efficacy and independence. More troubling to critics are attempts to avoid, delay, or weaken independent oversight practices that are in place. Public discussion of independent oversight could help

|

19 |

Electronic Privacy Information Center, Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Orders 1979-2007, updated May 8, 2008. Available at http://epic.org/privacy/wiretap/stats/fisa_stats.html. Some analysts interpret this fact to suggest that the FISA application process is more or less pro forma and does not provide a meaningful check on government power in this area, while others suggest that applications are done with particular care because the applicants know the applications will be carefully scrutinized. |

resolve these differences and raise trust in government efforts to protect privacy.

G.2.4

Collateral Benefits of Oversight

Ensuring compliance with policy is not the only benefit afforded by oversight. Indeed, administrators of government agencies face enormous challenges, not only from external pressures based on public concern over privacy, but also from internal struggles about how to motivate high performance while adhering to legal requirements and staying within budget.

Management strategies for achieving excellence in government agencies, corporations, and universities include many forms of internal review, measurement, and evaluation and a variety of strategies for external review. External reviews from consultants, advisory boards, or boards of visitors are designed to bring fresh perspectives that promote continuous improvement, while generating good will and respect from external stakeholders.

A well-designed oversight process can support the goal of continuous improvement and guide administrators in making organizational change, while raising public trust for an organization. Although many forms of oversight have been applied in corporate settings, the main approach is the board of directors. Such boards may be a weak form of oversight as they often mix internal with external participants who are less than independent. A stronger form of independent oversight and advice may come from external consultants or review panels that are convened for specific decisions or projects, but even stronger forms are possible.

For example, in the United States, corporate boards of directors are required to include an audit committee that is responsible for monitoring the external financial reporting process and related risks. An important role of the audit committee is to commission an external audit from an independent accounting firm, which is required annually for every publicly traded U.S. corporation by the SEC. These external audits are major events that provide independent oversight for financial matters with public reports to the SEC that become available to investors. In response to recent failures of independent oversight such as in the Enron and Worldcom bankruptcies, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) has substantially strengthened the rules.20