M

Public Opinion Data on U.S. Attitudes Toward Government Counterterrorism Efforts

M.1

INTRODUCTION

Since September 11, 2001 (9/11), Americans have been forced to confront conflict between the values of privacy and security more directly than at any other time in their history. On one hand, in view of the unprecedented threat of terrorism, citizens must depend on the government to provide for their own and the nation’s security. On the other hand, technological advances mean that government surveillance in the interests of national security is potentially more sweeping in scope and more exhaustive in detail than at any time in the past, and thus it may represent a greater degree of intrusion on privacy and other civil liberties than the American public has ever experienced. In this appendix, we review the results of public opinion surveys that gauge the public’s reaction to government surveillance measures and information-gathering activities designed to foster national security. We attempt to examine the public’s view of the conflict between such surveillance measures and preservation of civil liberties.

Prior to 9/11, the American public’s privacy attitudes were located in the broad context of a tradition of limited government and assertion of

NOTE: The material presented in this appendix was prepared by Amy Corning and Eleanor Singer of the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan, under contract to the National Research Council, for the committee responsible for this report. Apart from some minor editorial corrections, this appendix consists entirely of the original paper provided by Corning and Singer.

the individual rights of citizens. In the past, expanded government powers have been instituted to promote security during national emergencies, but after the emergency receded, such powers have normally been rescinded.1 Although this historical context is one crucial influence, attitudes have been further shaped by developments of the postwar period. The importance of civil rights was highlighted by the social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s, a period also characterized by growing distrust of government; the latter decade also brought legislation designed to secure individuals’ rights to privacy. During the 1980s, developments in computing and telecommunications laid the groundwork for new challenges to privacy rights. The public consistently opposed the consolidation of information on citizens in centralized files or databanks, and federal legislation attempted to preserve existing privacy protections in the context of new technological developments.2 By the 1990s, however, technological advances—including the rise of the Internet, the widespread adoption of wireless communication, the decoding of human DNA, the development of data mining software, increasing automation of government records, the increasing speed and decreasing cost of computing and online storage power—occurred so quickly that they outpaced efforts to modify legislation to protect privacy, as well as the public’s ability to fully comprehend their privacy implications, contributing to high salience of privacy considerations and concerns.3

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, thus occurred in a charged environment, in which the public already regarded both business and government as potential threats to privacy. Almost immediately, the passage of the Patriot Act in 2001 raised questions about the appropriate nature and scope of the government’s expanded powers and framed the public debate in terms of a sacrifice of civil liberties, including privacy, in the interests of national security. Citizens appeared willing to make such sacrifices at a time of national emergency, however, and in the months following 9/11, tolerance for government antiterrorism surveillance was extremely high. Nevertheless, the public did not uncritically accept government intrusions: to use Westin’s term, they exhibited “rational ambivalence” by simultaneously expressing support for surveillance and

concern about protection of civil liberties as the government employed its expanded powers in investigating potential terrorist threats.4

Like other analysts,5 we find that acceptance of government surveillance measures has diminished over the years since 9/11, and that people are now both less convinced of the need to cede privacy and other civil liberties in the course of terrorism investigation and personally less willing to give up their freedoms. We show that critical views are visible in the closely related domains of attitudes toward individual surveillance measures and toward recently revealed secret surveillance programs. More generally, public pessimism about protection of the right to privacy has increased.

Westin identified five influences on people’s attitudes toward the balance between security and civil liberties: perceptions of terrorist threat; assessment of government effectiveness in dealing with terrorism; perceptions of how government terrorism prevention programs are affecting civil liberties; prior attitudes toward security and civil liberties; and broader political orientations, which may in turn be shaped by demographic and other social background factors.6 This review confirms the role of these influences on public attitudes toward privacy and security in the post-9/11 era.

This examination of research on attitudes toward government surveillance since 9/11 leads us to draw the following general conclusions:

-

As time from a direct terrorist attack on U.S. soil increases, the public is growing less certain of the need to sacrifice civil liberties for terrorism prevention, less willing to make such sacrifices, and more concerned that government counterterrorism efforts will erode privacy.

-

Tolerance for most individual surveillance measures declined in the five years after 9/11. The public’s attitudes toward recently revealed monitoring programs are mixed, with no clear consensus.

-

There is no strong support for health information databases that could be used to identify bioterrorist attacks or other threats to public health.

-

However, few citizens feel that their privacy has been affected by the government’s antiterrorism efforts.

-

The public tends to defend civil liberties more vigorously in the abstract than in connection with threats for specific purposes. Despite increasingly critical attitudes toward surveillance, the public is quite willing to endorse specific measures, especially when the measures are justified as necessary to prevent terrorism.

-

However, most people are more tolerant of surveillance when it is aimed at specific racial or ethnic groups, when it concerns activities they do not engage in, or when they are not focusing on its potential personal impact. We note that people are not concerned about privacy in general, but rather with protecting the privacy of information about themselves.

-

People are concerned with control over decisions related to privacy.

-

Attitudes toward surveillance and the appropriate balance between rights and security are extremely sensitive to situational influences, particularly perceptions of threat.

-

The framing of survey questions, in terms of both wording and context, strongly influences the opinions elicited.

M.2

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

In this appendix, we examine data from relevant questions asked by major research organizations in surveys since September 11, 2001, incorporating data from before that point when they are directly comparable to the later data or when they are pertinent. This review concentrates on trends, based on the same or closely similar questions that have been asked at multiple time points; we occasionally discuss the results from questions asked at only one point in time, when the information is illuminating or when trend data on a particular subject are not available. We restrict this review to surveys using adult national samples (or occasionally, national samples of registered voters); for the most part, these surveys are conducted by telephone using random-digit-dialed (RDD) samples,7 although occasionally we report on surveys conducted by personal inter-

|

7 |

These survey results may be biased by the fact that most or all of the surveys used did not attempt to reach cell-phone-only respondents; that is, the phone numbers called were land lines. In an era in which many individuals are using cell phones only, these surveys will not have reached many of such individuals. An article by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press suggests that this problem is not currently biasing polls taken for the entire population, although it may very well be damaging estimates for certain subgroups (e.g., young adults) in which the use of a cell phone only is more common. (See S. Keeter, “How Serious Is Polling’s Cell-Only Problem? The Landline-less Are Different and Their Numbers Are Growing Fast,” Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, June 20, 2007, available at http://pewresearch.org/pubs/515/polling-cell-only-problem.) |

view. We have not reviewed Web surveys. In the few instances in which samples represent groups other than the U.S. national adult population, we indicate that in the text or relevant charts or tables.

Survey List and In-Text Citations. The Annex at the end of this appendix lists the surveys to which we refer, identifying research organizations and sponsors as well as details on administration dates, mode, and sample design. (Response rate information is not available.) The abbreviations used in the text to identify the survey research organizations are also listed. The source citations in the text and in charts and tables are keyed to this list via the abbreviation identifying the research organization and survey date. Source citations appear as close as possible to the reported data; in other words, for data reported in figures or tables, the sources are generally indicated on the figures or tables.

Response Rates. We alert readers that response rates to national RDD sample surveys have declined. In a study reported in 2006, mean response rates for 20 national media surveys were estimated at 22 percent, using American Association for Public Opinion Research response rates RR3 or RR4, with a minimum of 5 percent and a maximum of 40 percent. Mean response rates for surveys done by government contractors (N = 7 for such surveys) during the same period were estimated at 46 percent, with minimums of 28 percent and maximums of 70 percent.8

We also note that we have no way of detecting or estimating nonresponse bias. Recent research on the relationship between nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias indicates that there is no necessary relationship between the two.9 A 2003 Pew Research Center national study of nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias shows significant differences on only 7 of 84 items in a comparison of a survey achieving a 25 percent response rate and one achieving a 50 percent response rate through the use of more rigorous methods.10 Two other studies also report evidence that, despite very low response rates, nonresponse bias in the surveys examined has

been negligible.11 These findings cannot, however, be generalized to the surveys used for this current examination. Thus, the possibility of nonresponse bias in the findings reported cannot be ruled out, nor is there a way to estimate the direction of the bias, if it exists.

We can speculate that nonresponse bias in the surveys reviewed here might result, on one hand, in an overrepresentation of individuals especially concerned about privacy or civil liberties, if they are drawn to such survey topics; on the other hand, nonresponse might be greatest among those most worried about threats to privacy, if they refuse to participate in surveys. Of the over 100 surveys used in this review, however, most are general-purpose polls that include some questions about privacy or civil liberties among a larger number of questions on broad topics, such as current social and political affairs, health care attitudes or satisfaction with medical care, technology attitudes, terrorism, etc. Fewer than 1 in 10 of the surveys examined could be construed as focusing primarily or even substantially on privacy or civil liberties. Thus, it is unlikely that the survey topics would produce higher response among those concerned with privacy. We expect that whatever bias exists will be in the direction of excluding those most concerned about privacy and that the findings reported will tend to underestimate levels of privacy concern.

Sources of Data and Search Strategies. This examination draws on several different sources of survey data. First, we rely on univariate tabulations of opinion polling data that are in the public domain, available through the iPOLL Databank at the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at the University of Connecticut (http://www.ropercenter.uconn.edu/data_access/ipoll/ipoll.html) and through the Institute for Resource and Security Studies (IRSS) repository at the University of North Carolina (http://www.irss.unc.edu/odum/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=140).

We searched these repositories using combinations of the following keywords (or variants thereof): airport security, biometrics, bioterrorism, civil liberties, civil rights, data, database, data mining, health, medical, monitor, personal information, privacy, rights, safety, search, scan, screen, security, surveillance, technology, terrorism, trust, video.

Second, we searched the reports archived at the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (http://people-press.org/reports/) and data compiled by the Polling Report (http://www.pollingreport.com/).

Searching was an iterative process, in the course of which we added

new keywords. Thus, it frequently turned out that the surveys we identified through searches of the IRSS archives, the Pew reports, and the Polling Report were also archived at the Roper Center when we searched on the new keywords. Since the Roper Center archive is more complete with respect to details on methodology, and since it allows those interested to easily obtain further data from the cited surveys, we identify it as the source of data, even when we initially identified a survey by searching other sources.

Third, when tabulations of the original survey data are not available, we draw on reports that research organizations or sponsors have prepared and posted on the Internet. These reports were identified via Internet searches using the same keywords as for the data archive searches. When referring to data drawn from such reports, the source information included in the text identifies both the survey (listed by abbreviation in subsection M.8.3 in the Annex) and the report (listed in subsection M.8.4).

Finally, we refer to several articles by researchers who have conducted their own reviews of poll results or who have conducted independent research on related topics.

M.3

ORGANIZATION OF THIS APPENDIX

The remainder of this appendix is divided into four sections. In Section M.4, “General Privacy Attitudes,” we briefly review public opinion on privacy in general, not directly related to antiterrorism efforts, in order to establish a context for understanding attitudes toward government monitoring programs. Section M.5, “Government Surveillance” begins with an overview of responses to a variety of surveillance measures, as examined in repeated surveys conducted by Harris Interactive. We then review data on attitudes toward seven specific areas of surveillance or monitoring:

-

Communications monitoring

-

Monitoring of financial transactions

-

Video surveillance

-

Travel security

-

Biometric identification technologies

-

Government use of databases and data mining

-

Public health uses of medical information

Section M.6 is devoted to a consideration of attitudes toward the balance between defense of privacy and other civil rights that may interfere with effective terrorism investigation, on one hand, and terrorism pre-

vention measures that may curtail liberties, on the other. Here we review survey results on public assessments of the proper balance between liberty and security, as well as trends in perceptions of the need to exchange liberty for security and personal willingness to make such sacrifices. In the concluding section, we discuss several factors that affect beliefs about the proper balance between liberty and security.

M.4

GENERAL PRIVACY ATTITUDES

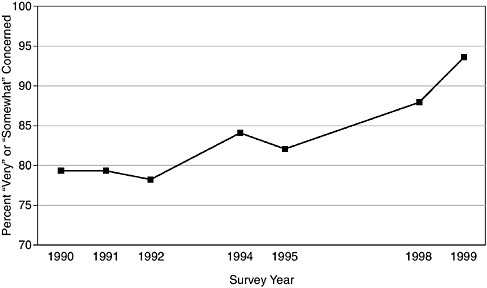

Figure M.1 displays results from a question asked by survey researchers throughout the 1990s: “How concerned are you about threats to your personal privacy in America today?” As the chart shows, respondents’ concern about this issue increased steadily throughout the decade; by the last years of the 1990s, roughly 9 in 10 respondents were either “very” or “somewhat” concerned about threats to personal privacy. Once privacy issues became even more salient after September 11, 2001, the question was presumably no longer able to discriminate effectively between levels of concern about privacy, and it was not asked again by survey organizations.

FIGURE M.1 “How concerned are you about threats to your personal privacy in America today?—very concerned, somewhat concerned, not very concerned, or not concerned at all?” (Harris Surveys, 1990-1999). SOURCE: A. Corning and E. Singer, 2003, “Surveys of U.S. Privacy Attitudes,” report prepared for the Center for Democracy and Technology.

Related data for the post-9/11 period, however, suggest that general concerns about privacy have not abated. For example, public perceptions of the right to privacy are characterized by increasing pessimism. In July 2002, respondents to a survey conducted by the Public Agenda Foundation were asked “Do you believe that the right to privacy is currently under serious threat, is it basically safe, or has it already been lost?” (Table M.1). One-third of respondents thought it was basically safe, while 41 percent thought it was under serious threat and one-quarter regarded it as already lost. By September 2005, when the question was repeated in a CBS/New York Times poll, over half thought it was under serious threat, and 30 percent thought it had already been lost. Just 16 percent regarded it as “basically safe.” Such pessimism may reflect generalized fears of privacy invasion, fueled by media reports of compromised security and ads that play to anxiety about fraud and identity theft; in addition, it may betray concerns about government intrusions on privacy in the post-9/11 era.

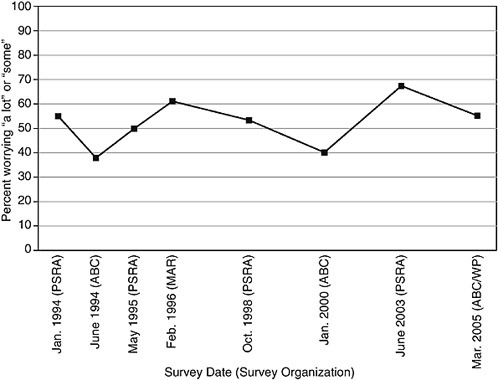

The perception that privacy is under threat is also due in part to concerns that the privacy of electronic information is difficult, if not impossible, to maintain. Over the past decade, survey researchers have repeated a question about online threats to privacy: “How much do you worry that computers and technology are being used to invade your privacy—is that something you worry about a lot, some, not much, or not at all?” As Figure M.2 shows, at most of the time points, half or more of respondents worried “some” or “a lot.” The fluctuations from one observation to the next are probably due to house differences and to question context effects,12 rather than to any substantive change in attitudes, and overall there appears to be a slight trend toward increasing worry about online privacy since 1994. (Considered separately, both the Princeton Survey Research Associates, PSRA, and the ABC surveys show parallel upward trends.) As Best et al. note,13 growing concern about online privacy may be attributed to frequent reports of unauthorized access to or loss of

TABLE M.1 Right to Privacy (Public Agenda Foundation and CBS/ New York Times Surveys)

|

|

July 2002 |

September 2005 |

|

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

“Do you believe that the right to privacy is currently under serious threat, is it basically safe, or has it already been lost?”a |

||

|

Basically safe |

34 |

16 |

|

Currently under serious threat |

41 |

52 |

|

Has already been lost |

24 |

30 |

|

Don’t know |

2 |

2 |

|

aCBS/NYT 9/05: “Do you believe that currently the right to privacy is basically safe, under serious threat, or has already been lost?” SOURCES: PAF/RMA 7/02; CBS/NYT 9/05. |

||

FIGURE M.2 “How much do you worry that computers and technology are being used to invade your privacy?” (surveys by PSRA, ABC News, and Marist College, 1994-2005). NOTE: Marist wording: “… that computers and advances in technology used to …” SOURCES: PSRA/TM 1/94, 5/95; ABC 6/94, 1/00; MAR 2/96; PSRA/PEW 10/98, 6/03; ABC/WP 3/05.

electronic data held by a wide variety of institutions, as well as to users’ experience with spam and viruses.

These data on electronic privacy suggest that the public identifies multiple threats to privacy; surveillance by the federal government may be the most visible and controversial, but it is far from the only, or even the most important threat, in the public’s view. In July 2002, respondents to a National Constitution Center survey regarded banks and credit card companies as the greatest threat to personal privacy (57 percent), while 29 percent identified the federal government as the greatest threat (PAF/ RMA 7/02). When a similar question was asked in 2005 by CBS/NYT, 61 percent thought banks and credit card companies, alone or in combination with other groups, posed the greatest threat, while 28 percent named the federal government alone or in combination with other groups (CBS/NYT 9/05). (Responses cannot be compared directly, because of differences in the response options offered.)

M.5

GOVERNMENT SURVEILLANCE

M.5.1

Trends in Attitudes Toward Surveillance Measures

Over the years since September 11, 2001, Harris Interactive has asked a series of questions about support for specific surveillance measures that have been implemented or considered by the U.S. government as part of its terrorism prevention programs. For most of the questions, six or eight observations are available, for the period beginning just one week after the terrorist attacks in September 2001 and extending to July 2006. Table M.2 displays percentages of respondents favoring each of the measures at each time point.

Support for nearly all the measures peaked in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, with support for stronger document and security checks and expanded undercover activities exceeding 90 percent. As the emotional response to the attacks subsided over the four years that followed, support for each of the measures declined, in many cases by more than 10 percentage points. As of the June 2005 observation, total decreases in support were fairly small for three of the more intrusive measures, which had not been as enthusiastically received in the first place: adoption of a national ID system, expanded camera surveillance in public places, and law enforcement monitoring of Internet discussions. In contrast, support for expanded monitoring of cell phone and e-mail communications—which had only barely received majority support in September 2001—had declined by 17 percentage points, to 37 percent, as of June 2005. At each time point it has been the least popular measure, by a margin of 9 or more percentage points.

TABLE M.2 Support for Government Surveillance Measures (Harris Surveys, 2001-2006)

|

|

September 2001a |

March 2002 |

February 2003 |

February 2004 |

September 2004 |

June 2005 |

February 2006 |

July 2006 |

|

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

Here are some increased powers of investigation that law enforcement agencies might use when dealing with people suspected of terrorist activity, which would also affect our civil liberties. For each, please say if you would favor or oppose it? (“Favor”) |

||||||||

|

Stronger document andphysical security checks for travelers |

93 |

89 |

84 |

84 |

83 |

81 |

84 |

— |

|

Stronger document and physical security checks for access to government and private office buildings |

92 |

89 |

82 |

85 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Expanded undercover activities to penetrate groups under suspicion |

93 |

88 |

81 |

80 |

82 |

76 |

82 |

— |

|

Use of facial recognition technology to scan for suspected terrorists at various locations and public events |

86 |

81 |

77 |

80 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

September 2001a |

March 2002 |

February 2003 |

February 2004 |

September 2004 |

June 2005 |

February 2006 |

July 2006 |

|

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

Issuance of a secure ID technique for persons to access government and business computer systems, to avoid disruptions |

84 |

78 |

75 |

76 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Closer monitoring of banking and credit card transactions, to trace funding sources |

81 |

72 |

67 |

64 |

67 |

62 |

66 |

61 |

|

Adoption of a national ID system for all U.S. citizens |

68 |

59 |

64 |

56 |

60 |

61 |

64 |

— |

|

Expanded camera surveillance on streets and in public places |

63 |

58 |

61 |

61 |

60 |

59 |

67 |

70 |

|

Law enforcement monitoring of Internet discussions in chat rooms and other forums |

63 |

55 |

54 |

50 |

59 |

57 |

60 |

62 |

|

Expanded government monitoring of cell phones and e-mail, to intercept communications |

54 |

44 |

44 |

36 |

39 |

37 |

44 |

52 |

|

aFieldwork conducted September 19-24, 2001. SOURCE: HI 9/01, 3/02, 2/03, 2/04, 9/04, 6/05, 2/06, 7/06. |

||||||||

Beginning with the February 2006 observation, however, most of the measures show an upturn in support, probably due to the London Underground bombings of July 2005. In particular, the growth in public approval for camera surveillance may have resulted from the role of video camera footage in establishing the identities of the London Underground bombers. A year after the London bombings, in July 2006, support for three of the measures—expanded camera surveillance, monitoring of chat rooms and other Internet forums, and expanded monitoring of cell phones and e-mail—continued to show increases.

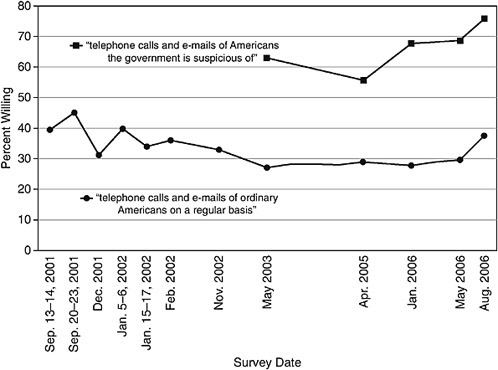

These data suggest several generalizations. First, people appear more willing to endorse measures that they believe are unlikely to affect them. Tolerance for undercover activities targeted at suspected groups has remained at high levels. Other data support this conclusion as well: Table M.3 shows results from questions about surveillance measures asked in Pew surveys, which reveal that acceptance of racial/ethnic profiling is also comparatively high. And in surveys carried out by CBS/ NYT, respondents were asked whether they “would be willing to allow government agencies to monitor the telephone calls and e-mail of ordinary Americans.” Beginning in 2003, they were also asked the same question with regard to the communications “of Americans the government is suspicious of.” The data, plotted in Figure M.3, indicate that support for monitoring the communications of people the government is suspicious of is much higher than support for monitoring those of ordinary Americans.

Second, people are more likely to accept measures that they do not regard as especially burdensome. Support has been highest for more rigorous security, both for travelers and for access to buildings; the added inconvenience represented by the extra checks may not seem significant to respondents. Acceptance of surveillance in public places also tends to be high. By contrast, measures intended to monitor the traditionally private domain of communications—whether Internet chat rooms or, especially, telephone and e-mail communication—have been the least accepted, at each time point.

M.5.2

Communications Monitoring

General Trends over Time. Two pieces of research focusing on communications monitoring confirm the Harris data trends, mirroring both the long-term decreases in support for monitoring and sensitivity to perceptions of increased threat. First, the CBS/NYT data displayed in Figure M.3 show that the trend for “ordinary Americans” displays the same pattern visible in Table M.2, with a slow decline after 9/11 but an upturn discernible in mid-2006; here the upturn probably represents a response

TABLE M.3 Support for Government Surveillance Measures (Pew Center/PSRA Surveys, 2001-2006)

|

|

September 2001 |

August 2002 |

January 2006 |

December 2006 |

||

|

Personal Wording |

Personal Wording |

Impersonal Wordinga |

Personal Wording |

Personal Wording |

Impersonal Wordinga |

|

|

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

“Would you favor or oppose the following measures to curb terrorism?” (“Favor”) |

||||||

|

Requiring that all citizens carry a national identity card at all times to show toa police officer on request |

70 |

59 |

— |

57 |

57 |

— |

|

Allowing airport personnel to do extra checks on passengers who appear to be of Middle-Eastern descent |

— |

59 |

— |

57 |

57 |

— |

|

Allowing the U.S. government to monitor your personal telephone calls and e-mails |

26 |

22b |

33 |

24 |

22b |

34 |

|

Allowing the U.S. government to monitor your credit card purchases |

40 |

32b |

43 |

29 |

26b |

42 |

|

aThe word “your” was omitted from the question text. Asked of Form 1 half sample. bAsked of Form 2 half sample. SOURCE: PSRA/PEW 9/01, 8/02, 1/06, 12/06. |

||||||

FIGURE M.3 “In order to reduce the threat of terrorism, would you be willing or not willing to allow government agencies to monitor the …” (surveys by CBS News, 2001-2006). SOURCES: CBS/NYT 9/01a, 9/01b, 12/01, 11/02, 1/06, 8/06; CBS 1/02a, 1/02b, 2/02, 5/03, 4/05, 5/06.

to media reports of an averted terrorist plot to bomb airplanes bound for the United States. The upturn for “Americans the government is suspicious of” shows an earlier increase as well, possibly in response to the London Underground bombings. Second, Pew Center survey questions on monitoring of communications reveal similar declines in support after the immediate post-9/11 period (Table M.3).

Importance of Question Wording. Taken together, the three sets of research by Harris, Pew, and CBS/NYT (shown in Tables M.2 and M.3 and Figure M.3) reveal the degree to which attitudes are dependent on specific question wording. The wording of the first Pew question, about a national ID program (Table M.3), is fairly similar in emphasis to the wording used in the Harris surveys (Table M.2). Levels of support correspond closely across the two questions, starting at 68-70 percent in September 2001 and remaining steady at about 60 percent thereafter. In the questions on monitoring of communications and credit card purchases shown

in Table M.3, however, Pew highlighted the potential personal impact of the measures, asking respondents how they would react to programs that would allow their own phone calls, e-mails, and credit card purchases to be monitored. The differences are striking: even in September 2001, 54 percent supported the Harris measure allowing the government to monitor phone calls and e-mail (Harris—Table M.2), but less than half as many reacted favorably to the possibility that their own telephone and e-mail communications might be monitored (Pew—Table M.3).14 Similarly, 81 percent approved of “closer monitoring of bank and credit card transactions” in 2001 (Harris—Table M.2), but again, just half as many were comfortable with the idea that their own purchases could be monitored (Pew—Table M.3).

At two time points, August 2002 and December 2006, Pew used a split-sample experiment that further confirms the impact of wording changes. In these experiments, half the sample was asked the questions about communications and credit card purchase monitoring in the usual form, while the other half of the sample heard the questions in a more impersonal form produced simply by omitting the word “your”: “Allowing the U.S. government to monitor personal telephone calls and e-mails”; “Allowing the U.S. government to monitor credit card purchases.” Results for the personal and impersonal wording are compared in Table M.3. On both measures, the impersonal wording boosted support by 11 or more percentage points at each observation.

Telephone Records Database Program. In May 2006, it was disclosed that the National Security Agency (NSA) was compiling a database containing the telephone call records of millions of ordinary American citizens, using information obtained from Verizon, AT&T, and BellSouth. Survey organizations responded to the ensuing controversy by asking respondents about their reactions. The public was divided: approval for the program ranged between 43 and 63 percent, with levels of support predictably varying by question wording (Table M.4). Gallup’s question, which emphasized the scope of the database and the participation of the telephone companies and mentioned terrorism only at the very beginning of a long question, showed the lowest support, at 43 percent. When questions mentioned a more menacing “threat of terrorism” or “terrorist activity,” as the CBS and Fox News questions did, about half of respondents favored the measure. The ABC News/WP question, which includes two mentions of terrorism and is the only question to note that

TABLE M.4 Four Questions on Attitudes Toward NSA’s Telephone Records Database Program, May 2006

|

|

Approve/Support/Consider Acceptable |

Disapprove/Oppose/Consider Unacceptable |

Unsure |

|

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

“As you may know, as part of its efforts to investigate terrorism, a federal government agency obtained records from three of the largest U.S. telephone companies in order to create a database of billions of telephone numbers dialed by Americans. Based on what you have read or heard about this program to collect phone records, would you say you approve or disapprove of this government program?” (Gallup/USA Today) |

43 |

51 |

6 |

|

“Do you approve or disapprove of the government collecting the phone call records of people in the U.S. in order to reduce the threat of terrorism?” (CBS News) |

51 |

44 |

5 |

|

“As part of a larger program to detect possible terrorist activity, do you support or oppose the National Security Agency collecting data on domestic phone calls and looking at calling patterns of Americans without listening in or recording the calls?”a (Opinion Dynamics/Fox News) |

52 |

41 |

6 |

|

“It’s been reported that the National Security Agency has been collecting the phone call records of tens of millions of Americans. It then analyzes calling patterns in an effort to identify possible terrorism suspects, without listening to or recording the conversations. Would you consider this an acceptable or unacceptable way for the federal government to investigate terrorism?” (ABC/ Washington Post) |

63 |

35 |

2 |

|

aNational sample of registered voters. SOURCES: GAL/USA 5/06, CBS 5/06, OD/FOX 5/06, ABC/WP 5/06. |

|||

the phone calls are not listened to, found that 63 percent considered the program acceptable.

The public’s ambivalence is reflected in mixed findings on concern about the program’s potential personal consequences. More than half (57 percent) said they would feel their privacy had been violated if they learned that their own phone company had provided their records to the government under the program (GAL/USA 5/06). But apart from such objections to phone companies releasing information without customers’ approval, respondents do not appear to be overly concerned about personal implications of the program. In answer to questions by Gallup and ABC, one-third of respondents said they would be “very” or “somewhat concerned/bothered” if they found out that the government had records of their phone calls (GAL/USA 5/06, ABC/WP 5/06). Yet despite the size of the database, most people seemed to regard this as an unlikely possibility: only one-quarter were “very” or “somewhat concerned” that the government might have their personal phone call records (CBS 5/06). Thus a minority, albeit a substantial one, expressed concern about the personal implications of the program.

When confronted with the conflicting values of investigating terrorism via the telephone records program on one hand, and the right to privacy on the other, respondents again displayed ambivalence, and different surveys showed majorities giving priority to each value. In the Gallup survey, the 43 percent who approved of the program (N = 349) were asked whether they approved because they felt the program did not “seriously violate” civil liberties or because they thought it was more important to investigate terrorism: 69 percent believed that terrorism investigation was the more important goal (GAL/USA 5/06). A survey conducted by the Winston Group (WIN 5/06; national sample of registered voters) found that 60 percent favored continuing the program because “we must do whatever we can within the law to prevent another terrorist attack,” while 36 percent thought it should be discontinued because “it infringes on the right to privacy” (4 percent were unsure). A PSRA study showed that 41 percent thought the program was “a necessary tool to combat terrorism,” while 53 percent found that it went “too far in invading people’s privacy,” and 6 percent were undecided (PSRA/NW 5/06). And when respondents to the CBS survey were asked whether phone companies should share their phone records with the government or whether that was an invasion of privacy, just 32 percent thought the phone companies should share that information, while 60 percent felt it was an invasion of privacy (CBS 5/06).

The variation in question wording, and consequently in results, makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about public attitudes toward the program. What seems clear, however, is that, despite generally low

support for surveillance of communications in the abstract, as shown by the Harris and particularly the PSRA/Pew results discussed earlier, the public exhibits greater tolerance for specific instances of surveillance, such as the telephone records database program—especially when the surveillance is justified as an antiterrorist measure.

Still, between one-third and two-thirds in each survey opposed the program. That opposition may betray public skepticism about the effectiveness and accuracy of the program. According to the CBS survey, 46 percent thought the phone call records database program would be “effective in reducing the threat of terrorism,” 43 percent thought it would not be effective, and 11 percent were uncertain. And in the Gallup survey, two-thirds were concerned that the program would misidentify innocent Americans (36 percent “very concerned” and 29 percent “somewhat concerned”).

Finally, the public exhibited no clear consensus even on the subject of whether the news media should disclose such secret counterterrorism efforts. In the Gallup poll, 47 percent thought the media should report on “the secret methods the government is using to fight terrorism,” while 49 percent thought they should not; an ABC News/WP poll found that 56 percent thought the news media were right, and 42 percent thought they were wrong to report on the program (ABC/WP 5/06).

M.5.3

Monitoring of Financial Transactions

Tables M.2 and M.3 show change in support for government monitoring of individuals’ credit card purchases in surveys conducted by Harris and PSRA/Pew between 2001 and 2006. Although the two organizations found different overall levels of support owing to specific question wording, both trends show a total decline of 14 to 20 percentage points in the approximately five-year period since September 2001. At each time point, however, support for the monitoring of financial transactions was greater than for the monitoring of communications.

Following the revelations about the NSA’s telephone call database program but prior to reports of systematic searches of international banking data carried out by the Central Intelligence Agency/Treasury Department, several other surveys asked respondents for their opinion on financial monitoring. Among the U.S. sample in a June 2006 survey sponsored by the German Marshall Fund, 39 percent supported “the government having greater authority to monitor citizens’ banking transactions” as part of the effort to prevent terrorism, but 58 percent opposed such powers, and 3 percent were not sure (TNS/GMF 6/06). And in a CBS May

2006 survey, only one-quarter of respondents thought that credit card companies should “share information about the buying patterns of their customers with the government” (CBS 5/06).

After the revelations about the CIA/Treasury Department program, a Los Angeles Times survey found that 65 percent of respondents considered government monitoring of international bank transfers an “acceptable” way to investigate terrorism (LAT 7/06)—roughly the same percentage favoring monitoring of financial transactions in general between 2003 and 2006, as shown by the Harris surveys (Table M.2). Also in July 2006, Harris found that 61 percent of respondents favored the monitoring of financial transactions, a decline of 5 percentage points compared with the previous observation (Table M.2), while Pew also found a slight decline (Table M.3). These data are limited, but they suggest that public support for the government monitoring of financial transactions either remained stable or declined slightly in response to information about the program.

M.5.4

Video Surveillance

Table M.2 shows that, despite initial declines in the years following September 2001, public support for video surveillance has been increasing. The percentages favoring increased video surveillance surpassed the September 2001 level (63 percent) in both February 2006 (67 percent) and July 2006 (70 percent). As noted earlier, the growing favorability may be due to the role of video cameras in identifying suspects in the London Underground bombings of 2005.

Other trend data on video surveillance attitudes also suggest that support is widespread, particularly when linked to terrorism prevention. In 1998, a CBS News poll asked respondents whether installing video cameras on city streets was “a good idea because they may help to reduce crime,” or “a bad idea because [they] may infringe on people’s privacy rights.” Although more than half thought such cameras were a good idea, 34 percent regarded the cameras as an infringement on privacy (CBS 3/98). The same question, repeated in 2002, generated similar results (CBS 4/02). In July 2005, after the London Underground bombings, the question was rephrased to mention reducing “the threat of terrorism” instead of reducing crime. This time, 71 percent of respondents considered video surveillance a good idea, and just 23 percent thought it a bad idea (CBS 7/05). Other data on attitudes to video surveillance at national monuments—not explicitly linked to crime or to terrorism—showed that 81 percent support such surveillance, with only 17 percent finding it an invasion of privacy (CBS 4/02).

M.5.5

Travel Security

Tighter airport security has been a source of frustration for travelers, and media reports perennially question the effectiveness of the measures. Nevertheless, the Harris data show higher levels of support for passenger screening and searches than for any other measure, both immediately after 9/11 and continuing through 2006 (see Table M.2).

While respondents are by no means fully convinced of airport security’s effectiveness, public confidence does not appear to be waning, perhaps because of the absence, since 9/11, of terrorism involving airliners. In 2002, Fox News asked a sample of registered voters whether they thought the “random frisks and bag searches at airport security checkpoints are mostly for show” or whether they were “effective ways to prevent future terrorist attacks.” The poll found that 41 percent thought the searches were for show and 45 percent thought they were effective, with 14 percent unsure (OD/FOX 4/02). In January and August 2006, CBS respondents were asked to evaluate the effectiveness of the government’s “screening and searches of passengers who travel on airplanes in the U.S.” While only 24 and 21 percent thought they were “very effective” in January and August, respectively, 53 percent in January and 61 percent in August found them “somewhat effective” (CBS 1/06 and 8/06). The Fox and CBS questions are of course not directly comparable, but there is no evidence of a decline in public confidence.

However, travel security now extends well beyond such airport searches to encompass such issues as what information airlines may collect and share with the government. When asked in 2006 whether airport security officials should have access to “passengers’ personal data like their previous travel, credit card information, email addresses, telephone numbers and hotel or car reservations linked to their flight,” just over half of respondents agreed that officials should have such access, while 43 percent said they should not (SRBI/TIME 8/06). When the public is asked whether “the government should have the right to collect personal information about travelers,” support is somewhat lower (IR/QNS 6/06). One-quarter thought the government should have the right under any circumstances, and another 17 percent only with the traveler’s consent. Still, a further 39 percent favored collecting such information if the traveler was suspected of some wrongdoing. A 2003 survey for the Council for Excellence in Government proposed a “smart card” that would store personal information digitally and could facilitate check-in, but it might also lead to the abuse of information; only 27 percent felt that the benefits of such a card outweighed the concerns, while 54 percent thought the concerns outweighed the benefits (H&T 2/03).

In addition, there is the question of what the airlines or the gov-

ernment may do with information they have collected. A Council for Excellence in Government survey in February 2004 (H&T 2/04) showed that 59 percent of respondents supported airline companies’ sharing of information with the government “if there is any chance that it will help prevent terrorism,” but 36 percent thought the government should not have access to the information “because that information is private and there are other things the government can do to prevent terrorism.” In the Ipsos-Reid survey (IR/QNS 6/06), 73 percent would allow the government to share traveler information with foreign governments—but only 21 percent thought the government should be allowed to share information about any traveler, while 52 percent would restrict such sharing to information about travelers suspected of wrongdoing.

M.5.6

Biometric Identification Technologies

A small handful of studies have attempted to gauge public attitudes toward biometric technologies that may be used for the identification of terrorists. As indicated in Table M.2, public support for the use of facial recognition technology declined somewhat after 9/11 but remained at high levels. In February 2004, the most recent observation available, 80 percent favored the use of such technology.

Other surveys have examined attitudes toward biometrics in the context of enhancing airport security. In a survey conducted in late September 2001 (HI/ID 9/01a), respondents were read the following description of an electronic fingerprint scanning process that could facilitate check-in and security procedures:

I would like to read you a description of a new airport security solution and get your opinion. This new solution uses an electronic image of a fingerprint for a “real-time” background check to ensure that passengers, airline personnel, and airport employees are not linked with criminal or terrorist activities. The fingerprint images of people with no criminal or terrorist associations are immediately destroyed to protect the individual’s privacy. The fingerprint image is used to link passengers to their boarding pass, baggage and passport control for better security.

Based on this description, and in the tense atmosphere immediately following 9/11, public support was substantial: 76 percent said such a new system would be “extremely” or “very valuable,” and a further 16 percent thought it would be “somewhat valuable.” Respondents were also overwhelmingly willing to have their own fingerprints scanned for airport security: 82 percent would be “very willing,” and an additional 13 percent “would do it reluctantly.” Only 4 percent “would not do it under any circumstances.”

Several days later, in a subsequent survey by the same sponsor and organization, respondents were asked to choose between the fingerprint scan and an electronic facial scan:

I want to explain two technologies that are being offered up as important solutions for airport security. The first is an electronic finger scan. Fingerprints are recognized as a highly accurate means of identification—even among identical twins. This new solution uses an electronic image of a fingerprint for a “real-time” background check to ensure that passengers, airline personnel, and airport employees are not linked with criminal or terrorist activities. The fingerprint images of people with no criminal or terrorist associations are immediately destroyed to protect the individual’s privacy.

The second is an electronic facial scan. With this solution, a camera captures images of all people in the airport within range of the camera to provide a “real-time” background check against known criminals or terrorists. The solution is automatic and does not require a person’s permission or knowledge that it is occurring. This solution is convenient. However, there are more likely to be errors in distinguishing between people with very similar appearance, especially identical twins. Additionally, changes in facial hair or cosmetic surgery may make it difficult to provide an accurate match.

After hearing these descriptions, respondents rated the value of each method. Attitudes toward the fingerprint scan were again very favorable, closely matching the previous results. Clearly, the question portrays the facial scan as the less palatable option—not only is it more susceptible to errors, but it also can be used without consent or even knowledge. Not surprisingly, the facial scan ratings were substantially lower, with just 28 percent considering it “extremely” or “very valuable,” and 44 percent finding it “somewhat valuable” (HI/ID 9/01b).

More recent data on attitudes toward the use of biometric technology for security purposes are not available, but data from 2006 do indicate that this is an area about which the public is still not well informed. The IpsosReid study found that, in the United States, just 5 percent of respondents considered themselves “very knowledgeable” about “biometrics for facial and other bodily recognition,” and only 24 percent said they were “somewhat knowledgeable” about the technology (IR/QNS 6/06).

M.5.7

Government Use of Databases and Data Mining

Reports about the telephone records database program, discussed separately above, offer a view of public reaction to a specific instance of government compilation and searching of data. But in general, does the

public feel it is appropriate for the government to use such methods? The few surveys that have examined this issue suggest that there is support for database searches by the government, particularly when presented as instrumental to counterterrorism efforts. In December 2002, respondents to a poll by the Los Angeles Times were told that

The Department of Defense is developing a program which could compile information from sources such as phone calls, e-mails, web searches, financial records, purchases, school records, medical records and travel histories to provide a database of information about individuals in the United States. Supporters of the system say that it will provide a powerful tool for hunting terrorists. Opponents say it is an invasion of individual privacy by the government. (LAT 12/02)

Roughly equal proportions expressed support for the program (31 percent) and opposition to it (36 percent). However, respondents’ lack of knowledge about data mining was reflected in the large percentage saying they hadn’t heard enough to judge (28 percent). (Indeed, the Ipsos-Reid survey [IR/QNS 6/06] indicates that respondents were somewhat more knowledgeable about “data mining of personal information” than about biometrics, but still not well informed. In all, 11 percent said they were “very knowledgeable” about it, and 30 percent “somewhat knowledgeable,” leaving more than half “not very” or “not at all knowledgeable.”)

In early 2003, another study asked respondents to make a similar choice between the competing priorities of terrorism investigation and privacy with respect to government searches of “existing databases, such as those for Social Security” (H&T 2/03). Again, respondents were divided, with 49 percent finding it “appropriate” for government to carry out such searches, and 42 percent finding it “not appropriate.” (Both percentages are higher than in the Los Angeles Times survey because no “don’t know enough” option was explicitly offered.)

When respondents are not forced to choose between terrorism prevention and privacy, they express substantial concern about such efforts. In May 2006, in the context of questions about the telephone call records database program, Gallup asked respondents, “How concerned are you that the government is gathering other information on the general public, such as their bank records or Internet usage?” (GAL/USA 5/06). This question mentions only two of the possible personal information sources listed in the Los Angeles Times description of the Defense Department program. Nonetheless, 45 percent were “very concerned” and 22 percent “somewhat concerned” about such information-gathering.

M.5.8

Public Health Uses of Medical Information

Privacy of Medical Information. Previous studies indicate high levels of concern about the privacy of health care information.15 In 1999, Harris found that 54 percent of respondents were “very concerned” and 29 percent “somewhat concerned” about protecting the privacy of their health and medical information (HARRIS 4/99). A Gallup survey in 2000 found that over three-quarters of respondents thought it was “very important” that their medical records be kept confidential (Corning and Singer 2003). (The questions are worded differently, so no conclusions about trends can be drawn from these data).

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), with provisions designed to protect the privacy of individuals’ health information, took effect in 2003. The 2005 National Consumer Health Privacy Survey was partly devoted to an evaluation of the impact of HIPAA on public attitudes, but the results were not encouraging. The study found that, although 67 percent of respondents claimed to be aware of federal laws protecting the privacy and confidentiality of medical records and 59 percent could recall receiving a privacy notice, only 27 percent thought they now had more rights than before. The study recorded high levels of concern about medical privacy: 67 percent of respondents overall and 73 percent of those belonging to an ethnic minority were “very” or “somewhat concerned” about the privacy of their “personal medical records.”16 And 52 percent of respondents were worried that insurance claims information might be used against them by their employers—an increase of 16 percentage points over the 1999 figure (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; California Health Care Foundation 2005).

Concern about medical privacy may in part reflect a lack of trust in the confidentiality of shared information. The Health Confidence Survey, conducted in 1999 and 2001-2003, found that just under half of respondents had high confidence that their medical records were kept confidential (GRN/EBRI 5/99, 4/01, 4/02, 4/03; there is no evidence of systematic change over the four observations available). In the National Consumer Health Privacy Survey, one-quarter of respondents were aware of incidents in which the privacy of personal information had been compromised, and those who were aware of such privacy breaches said that such

incidents had contributed to their concern about the privacy of their own health records (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005).

Several surveys have compared concern about privacy in different domains, finding that levels of concern with regard to medical information are high. Even in 1978, Harris reported that 65 percent of respondents thought that it was important for Congress to pass additional privacy legislation in the area of medicine and health, as well as in the area of insurance—a larger proportion than favored such legislation for employment, mailing lists, credit cards, telephone call records, or public opinion polling (HARRIS 11/78). More recently, financial privacy concerns have exceeded concerns about medical records. As mentioned above, 54 percent of respondents in the 1999 Harris survey were concerned about protection of health and medical privacy, compared with 64 percent who were concerned about protecting privacy of information about their financial assets (HARRIS 4/99). And in 1995, PSRA found that more than half of respondents were “very” or “somewhat concerned” about “threats to privacy from growing computer use” in the areas of bank accounts (65 percent), credit cards (69 percent), and job and health records (59 percent; PSRA/NW 2/95).

Attitudes Toward Electronic Medical Records. Indeed, Corning and Singer (2003) note that the public’s concerns about the privacy of health and medical information are due in part to the computerization of health and medical records and to perceptions of the vulnerability of computerized records to hacking or other unauthorized use. A 1999 survey found that 59 percent of respondents were worried “that some unauthorized person might gain access to your financial records or personal information such as health records on the Internet” (ICR/NPR 11/99). Of those, 36 percent were “very worried” about such unauthorized access. The Pew Research Center in 2000 found that 60 percent thought it would be “a bad thing” if “your health care provider put your medical records on a secure Internet Web site that only you could access with a personal password,” because “you would worry about other people seeing your health records” (PSRA/PEW 7/00). The 2005 National Consumer Health Privacy Survey found that 58 percent of respondents thought medical records were “very” or “somewhat secure” in electronic format, compared with 66 percent in paper format (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005). And in the 2005 Health Confidence Survey, just 10 percent said they were “extremely” or “very confident” that their medical records would remain confidential if they were “stored electronically and shared through the Internet,” 20 percent were “somewhat confident,” and 69 percent were “not too” or “not at all confident” (GRN/EBRI 6/05).

Incidents in which the privacy of personal information stored elec-

tronically has been compromised have tended to increase concern about online medical record-keeping (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005). A Markle Foundation study in 200617 found that 65 percent of respondents were interested in storing and accessing their medical records in electronic format, but 80 percent were worried about identity theft or fraud, and 77 percent were worried about the information being used for marketing purposes (LRP/AV 11/06; Markle Foundation 2006).

Opposition to National Medical Databases. Such concerns are likely to have contributed to public opposition to the establishment of national databases that would store medical information. Opposition to such databases and to proposed systems of medical identification numbers ranges from moderate to nearly unanimous, depending on the question asked. For example, in 1992, 56 percent of respondents had “a great deal” of concern about “a health insurance company putting medical information about you into a computer information bank that others have access to” (RA/ACLUF 11/92, survey conducted via personal interview). Similarly, a 1998 PSRA survey examined attitudes toward a system of medical identification numbers. After answering a series of questions about potential risks and benefits of the proposed system, respondents answered a summary question, which showed that 52 percent would oppose such a system (PSRA/CHCF 11/98). In 2000, Gallup asked respondents, “Would you support a plan that requires every American, including you, to be assigned a medical identification number, similar to a social security number, to track your medical records and place them in a national computer database without your permission?” In response to that question, 91 percent of respondents opposed the plan (GAL/IHF 8/00).

Support for Public Health Uses of Medical Records. There have been few attempts to gauge attitudes toward the sharing of medical information for public health purposes, such as the conduct of research on health care, detection of disease outbreaks, or identification of bioterrorist attacks. The limited data available suggest that public support for such uses of medical information varies substantially depending on the safeguards specified, but it is far from universal. In the National Consumer Health Privacy Survey, only 30 percent of respondents were willing to share their medical information with doctors not involved in their care, and only 20 percent with government agencies (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005). More-

|

17 |

Markle Foundation, Survey Finds Americans Want Electronic Personal Health Information to Improve Own Health Care, 2006. Available at http://www.markle.org/downloadable_assets/research_doc_120706.pdf. [Accessed 3/10/07] |

over, just half of respondents in that survey believed they had a “duty” to share medical information in order to improve health care.

Guarantees of anonymity may boost support: in 2003, Parade Magazine asked respondents whether, “assuming that there is no way that anyone will have access to your identity,” they would be willing to release health information for various purposes. A total of 69 percent said they would share health information “so that doctors and hospitals can try to improve their services”; 67 percent, in order for “researchers to learn about the quality of health care, disease treatment, and prevention, and other related issues”; and 56 percent, so that “public health officials can scan for bio-terrorist attacks” (CRC/PAR 12/03). The Markle Foundation’s most recent survey questions also provided for the protection of patient identity and found somewhat greater enthusiasm for the sharing of medical data: 73 percent would be willing to release their information to detect outbreaks of disease, 72 percent for research on improving the quality of care, and 58 percent to detect bioterrorist attacks (LRP/AV 11/06; Markle Foundation 2006).18

Control and Consent. The desire for control over personal medical information is a recurrent theme in the research on attitudes toward online medical record-keeping. In general, those who are willing to accept the online storage of medical records appear to be motivated by perceived personal benefits (FOR/CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005). Some of these benefits take the form of increased control over the content of medical records: in the Markle Foundation survey, 91 percent of respondents wanted to have access to electronic health records in order to “see what their doctors write down,” and 84 percent in order to check for errors (LRP/AV 11/06; Markle Foundation 2006). Other types of perceived personal benefits, such as better coordination of medical treatment (FOR/ CHCF Summer/05; CHCF 2005) or reductions in unnecessary procedures (LRP/AV 11/06; Markle Foundation 2006) also tend to incline respondents more positively toward electronic medical record-keeping.

In addition to seeking greater control over what is in the medical record, survey respondents also express a desire for control over decisions about the release of medical information. In data from the 1990s, Singer, Shapiro, and Jacobs (1997)19 found broad support for individual consent

prior to the release of medical data to those not involved in treatment. Respondents also preferred to require that the patient’s permission be obtained for the use of medical records in research, even when the patient was not personally identified; 56 percent thought that general advance consent was not satisfactory and that permission should be required each time the record was accessed. Corning and Singer (2003) note that a strong majority of respondents to the 1998 CHCF survey thought that requiring individual consent before using data would be an effective way to protect privacy (PSRA/CHCF 11/98; CHCF 1999). Finally, the Markle Foundation’s (2006) report noted that respondents “want to have some control over the use of their information” for research or public health purposes.

The implications of these findings for public support of databases designed to monitor public health threats are threefold. First, concerns about privacy make respondents hesitant about any online health database system. Second, respondents expect to exert no small degree of control over how their medical information is used and to whom it is released. Third, when respondents perceive personal benefits, they are more willing to consider online storage and sharing of information, but they do not appear to be motivated to share information by broader concerns about social well-being or by any sense of civic duty. Thus, to the extent that members of the public regard disease outbreaks or bioterrorist attacks as remote possibilities that will probably not affect them directly, they are unlikely to wish to share medical information to help track such occurrences.

M.6

THE BALANCE BETWEEN CIVIL LIBERTIES AND TERRORISM INVESTIGATION

In recent years, survey organizations have used several broad questions asking respondents to weigh the competing priorities of terrorism investigation, on one hand, and protection of privacy or civil liberties, on the other. Although such questions are artificial in that they present the conflict between protection of individual rights and security in extreme, all-or-nothing terms, they do reflect the reality that support for civil rights is not an absolute value, but is dependent on judgments about the importance of other strongly held values.20 In this section we review data from such forced-choice questions to examine public willingness to exchange privacy for security. We also examine public perceptions of the

need to sacrifice civil liberties, as well as personal willingness to make such sacrifices.

M.6.1

Civil Liberties Versus Terrorism Prevention

Between 2002 and 2006, the following question was included in nine different surveys, mostly conducted by Gallup in conjunction with CNN and USA Today, but on two occasions conducted by Quinnipiac University:

Which comes closer to your view? The government should take all steps necessary to prevent additional acts of terrorism in the U.S., even if it means your basic civil liberties would be violated. OR: The government should take steps to prevent additional acts of terrorism, but not if those steps would violate your basic civil liberties.

And, focusing more specifically on privacy, ABC News/WP asked:

What do you think is more important right now—for the FBI [federal government] to investigate possible terrorist threats, even if that intrudes on personal privacy, or for the FBI [federal government] not to intrude on personal privacy, even if that limits its ability to investigate possible terrorist threats?”21

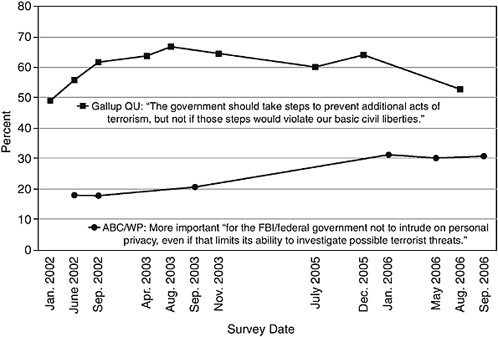

For each question, the trends for percentages choosing the civil liberties–oriented options are plotted in Figure M.4, which shows graphically the increasing affirmation of civil liberties since 9/11. Shortly after 9/11, in January 2002, 47 percent thought that “the government should take all steps necessary” for terrorism prevention (data not shown), but roughly half of respondents defended the preservation of civil liberties. By December 2005, just after the government had confirmed the existence of its warrantless monitoring program, 65 percent favored protection of civil liberties in the course of terrorism prevention. When “personal privacy” is singled out, as in the ABC/WP question, the overall percentages defending privacy against investigative measures are lower, but the trend is similar.22

The trend for another forced-choice question is plotted in Figure M.5. Respondents were asked, “What concerns you more right now? That

FIGURE M.4 Support for preserving privacy/civil liberties in the course of terrorism prevention (surveys by Gallup, Quinnipiac University, ABC, 2002-2006). SOURCES: Gallup/QU: GAL/CNN/USA 1/02, 6/02, 9/02, 4/03, 8/03, 12/05; GAL 11/03; QU 7/05, 8/06. ABC/Washington Post: ABC/WP 6/02, 1/06, 5/06; ABC 9/02, 9/03, 9/06.

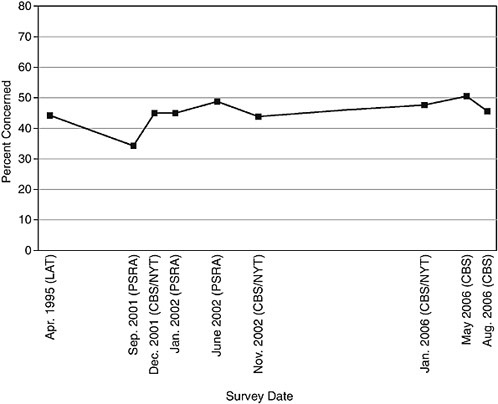

the government will fail to enact strong anti-terrorism laws, or that the government will enact new anti-terrorism laws which excessively restrict the average person’s civil liberties?” (Responses to the second option are plotted.) Figure M.5 shows that since September 2001, concern for preserving civil liberties has increased, and has remained at high levels or even grown slightly since 2002. A similar question, examining concerns specifically about privacy, was included in NBC/WSJ polls: “Which worries you more—that the United States will not go far enough in monitoring the activities and communications of potential terrorists living in the United States, or that the United States will go too far and violate the privacy rights of average citizens?” In December 2002, 31 percent were more worried that the United States would go too far; by July 2006, that figure had increased to 45 percent (H&T/NBC/WSJ 12/02, H&I/NBC/ WSJ 7/06). Other observations are not available, but the trend conforms to that for the question asking more broadly about civil rights.

The public’s concern does not appear to be based on any personal experience of privacy intrusions resulting from government efforts at

FIGURE M.5 Concern that government will enact anti-terrorism laws that restrict civil liberties (surveys by Los Angeles Times, PSRA, and CBS News, 1995-2006). SOURCES: LAT 4/95, PSRA/PEW 9/01, 1/02, 6/02; CBS/NYT 12/01, 11/02, 1/06; CBS 5/06, 8/06.

terrorism prevention. When Harris asked a question phrased in more personal terms—”How much do you feel government anti-terrorist programs have taken your own personal privacy away since September 11, 2001?”—perceptions showed stability over the same period (Table M.5). At each time point, a majority felt that their privacy had not been affected at all or had been affected “only a little.”

Sensitivity to Perceptions of Threat. Attitudes toward the proper balance between terrorism investigation and protection of civil liberties are clearly responsive to changes in threat perception. Such volatility is especially visible in responses to the Gallup/QU question (Figure M.4), which show declines in support for civil liberties at the July 2005 and August 2006 observations, which occurred just after the London Underground bombings and the reports of planned terrorist attacks on transatlantic

TABLE M.5 Impact on Personal Privacy of Government Antiterrorist Programs (Harris Surveys, 2004-2006)

|

|

February 2004 |

September 2004 |

June 2005 |

February 2006 |

|

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

Percent |

|

|

“How much do you feel government anti-terrorist programs have taken your own personal privacy away since September 11, 2001 (the date of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon)?” |

||||

|

A great deal |

8 |

8 |

10 |

7 |

|

Quite a lot |

6 |

9 |

7 |

7 |

|

A moderate amount |

22 |

21 |

24 |

23 |

|

Only a little |

29 |

26 |

25 |

28 |

|

None at all |

35 |

35 |

32 |

35 |

|

Not sure/NA |

1 |

1 |

1 |

— |

|

SOURCE: HI 2/04, 9/04, 6/05, 2/06. |

||||

flights, respectively.23 Responses to the ABC/WP question, which asked specifically about privacy, appear less sensitive, perhaps partly as a result of the timing of the observations. It may also be that the public regards such rights as due process and personal freedom as greater obstacles to terrorism investigation than privacy as such, but of course those rights have important privacy dimensions as well. Concern for preserving civil liberties (Figure M.5) has also been more stable, though we note that the peak in May 2006 coincided with reports on the NSA telephone records database.24 Thus, it is not only attitudes toward specific surveillance measures that are responsive to perceptions of increased threat (see Table M.2

and Figure M.3), but also broader prioritizations of individual rights and terrorism investigation.

M.6.2

Privacy Costs of Terrorism Investigation

In 1996, well before the events of 9/11 and even prior to several terrorist attacks on U.S. interests, 69 percent of respondents to an NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey said they would support “new laws to strengthen security measures against terrorism, even if that meant reducing privacy protections such as limits on government searches and wire-tapping” (H&T/NBC/WSJ 8/96). Thus it should come as no surprise that, in recent years, majorities of respondents recognize that terrorism investigation comes at a cost to privacy. In surveys conducted in September 2003, January 2006, and September 2006, between 58 and 64 percent agreed that, “in investigating terrorism … federal agencies like the FBI are intruding on some Americans’ privacy rights” (ABC 9/03, 9/06; ABC/WP 1/06). Yet between 49 and 63 percent of those who regarded the investigations as infringing on privacy rights thought the loss of privacy was justified (ABC 9/03, 9/06; ABC/WP 1/06).

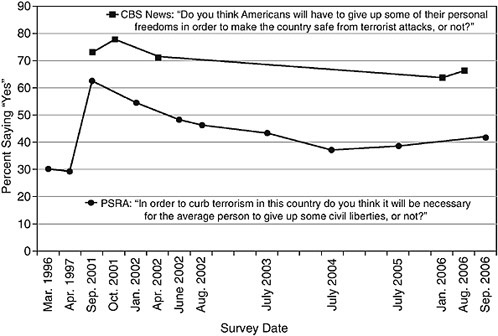

Further evidence of the public’s belief that sacrifices of civil liberties or personal freedoms will be needed in order to combat terrorism comes from two questions asked between March 1996 and August 2006. During that period, the Pew Research Center/PSRA asked, “In order to curb terrorism in this country, do you think it will be necessary for the average person to give up some civil liberties, or not?”25 And beginning in September 2001, CBS News asked, “Do you think Americans will have to give up some of their personal freedoms in order to make the country safe from terrorist attacks, or not?” The two trends are shown in Figure M.6. The overall difference between proportions agreeing with the two different propositions can probably be attributed to the difference between CBS News’ higher bar of making “the country safe” from threatening-sounding “terrorist attacks” (versus the more measured “curb terrorism” in the Pew/PSRA studies).

Both trends show the same pattern, however: percentages believing that sacrifices would be necessary were highest immediately after September 11, 2001. With increasing distance from those events, the public became less convinced of the need for sacrifices. Yet even when the percentages agreeing that sacrifices of civil liberties would be called for were at their lowest post-9/11 level, in July 2004, they had still not returned to the levels of the mid-1990s.

FIGURE M.6 Beliefs about need to give up civil liberties in order to curb terrorism (surveys by PSRA and CBS News, 1996-2006). SOURCES: PSRA: PSRA/PEW 3/96, 4/97, 1/02, 6/02, 7/03, 7/04, 7/05, 9/06; PSRA/NW 9/01, 8/02. CBS: CBS/ NYT 9/01a, 8/06; CBS 10/01, 4/02, 1/06.

M.6.3

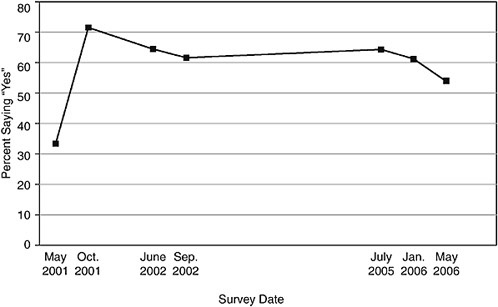

Personal Willingness to Sacrifice Freedoms

Public beliefs about the need for sacrifice at the national level appear to translate into personal willingness to make sacrifices as well. When respondents are asked whether they themselves would “give up some of [their] personal freedom in order to reduce the threat of terrorism,” substantial proportions say they are willing to do so. Figure M.7 shows that the trend on this question, too, conforms to the pattern discerned earlier. Again, there is an early observation, in May 2001, that serves as a pre-9/11 baseline: at that point, 33 percent said they would be willing to sacrifice some freedom, a figure that leaped to 71 percent after 9/11. The curve shows a decline over the next 12 months to 61 percent, where it remains until dropping again in January and May 2006. At the time of those surveys, respondents may have felt less inclined to consider further sacrifices, perhaps having become aware—after hearing reports about the government’s warrantless monitoring and telephone call records database programs—that they were already giving up more freedoms than they had realized. Still, the low point in May 2006 of 54 percent does not approach the pre-9/11 figure of 33 percent, suggesting that 9/11 may have