Managing Threats and Ensuring Healthy Communities: Health of the Public

Public health is fundamental to every individual’s health. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee in 1988 described the mission of public health as fulfilling society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy. Yet each individual’s health and well-being are shaped by the interactions of genetic endowment, environmental exposures, lifestyle and food choices, social conditions, income, and medical care. Collectively, these factors shape health at the population level—the domain of public health.

As a reflection of its broad spectrum, public health is perhaps the most diverse area the IOM investigates.

As a reflection of its broad spectrum, public health is perhaps the most diverse area the IOM investigates. The studies deal with important—and sometimes contentious—challenges that affect people from every walk of life, in every part of the country.

Preventing disease, early detection, and effective treatment

Since its founding, the IOM has consistently stressed the value of prevention of disease, a core tenet of public health. In studies ranging from core principles and needs in the field to specific issues such as health disparities, vaccine safety, smoking cessation, and reducing environmental hazards, the IOM continues to advance the best ways to ensure the public’s health.

Improving vaccines

In the United States and worldwide, vaccines have proved to be the most potent and cost-effective means of controlling infectious diseases. However, vaccines have yet to achieve their full potential.

In 1994, the U.S. government implemented a National Vaccine Plan that charted a route to more fully capture the promise of vaccines. Administered by the National Vaccine Program Office (NVPO) of the Department of Health and Human Services, the plan had four main goals: to develop new and improved vaccines; to ensure the optimal safety and effectiveness of vaccines and immunization; to better educate the public and members of the health professions on the benefits and risks of immunizations; and to achieve better use of existing vaccines to prevent disease, disability, and death. The plan, which offered more than 70 strategies for achieving its objectives, has recorded numerous successes since its implementation. But recent years also have kindled awareness that the plan needs to be modified to meet new challenges and opportunities.

Working in coordination with a number of federal agencies, the NVPO now is in the preliminary stages of updating the plan, and the partners turned to the IOM for assistance. Initial Guidance for an Update of the National Vaccine Plan: A Letter Report to the National Vaccine Program Office (2008) examines the goals, objectives, strategies, and anticipated outcomes of the original plan; explores how it was developed; and critiques the initial draft update that was proposed. Based on this analysis, the report identifies six specific “content” areas in which technical aspects of the 1994 plan might be improved and four “methodology” areas that might be strengthened in the process of updating the plan.

The report urges the inclusion of stakeholders beyond federal agencies in framing the plan’s scope, goals, and objectives. Additional contributors should include the pharmaceutical industry, insurers, health care providers and other purchasers of health care services, researchers across a range of basic and applied sciences, state and local public health agencies responsible for vaccine delivery, schools and day care centers, foundations and other not-for-profit organizations, the mass media, and, importantly, the public (including people with varying perspectives on the value of immunization), among others. Following the release of this initial guidance, the committee began its review of the draft update of the vaccine plan, which will be released late in 2009. It convened meetings of stakeholders in medicine, public health, and vaccinology to discuss the five goals laid out in the draft plan.

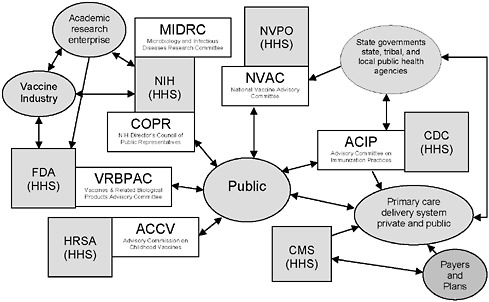

FIGURE 6-1 Federal advisory committees and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) agencies associated with vaccine- or immunization-specific programs.

NOTE: This figure is intended to illustrate some aspects of the immunization system’s complexity, not to be a complete description of the system. A number of federal advisory committees exist to provide advice and guidance to agencies in HHS. Four such committees, as well as two additional relevant committees, are depicted in the figure.

Legend: Gray boxes represent federal agencies in HHS (other departments, such as the Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs, and Homeland Security, also play important roles in the immunization system); white boxes represent federal advisory committees associated with HHS agencies, and gray ovals represent other stakeholders.

Acronyms: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NVPO = National Vaccine Program Office.

ACCV includes attorneys for injured children and for industry; NVAC Includes public, industry, state public health, and health care (AHIP) representation; ACIP includes public and state and local public health representation and liaisons to the vaccine industry and professional associations; COPR includes patients, family members of patients, health care and education professionals and members of the general public who advise the Director of the NIH on “matters of public interest, outreach and participation in NIH’s research-related activities;” VRBPAC includes public and nonvoting industry representation.

SOURCE: Initial Guidance for an Update of the National Vaccine Plan: A Letter Report to the National Vaccine Program Office, p. 9.

For many years the IOM has been involved in evaluating evidence concerning adverse health effects that may be associated with specific vaccines covered by the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. In 2009, the IOM began a new study to review the epidemiological, clinical, and biological evidence relating to the health effects of varicella zoster vaccine,

influenza vaccines, hepatitis B vaccine, human papillomavirus vaccine, and possibly others. The upcoming reports will consider whether a specific vaccine is related to a specific adverse event.

Helping to improve medication safety

Each year, people taking medications as outpatients experience more than a million harmful consequences that result in a trip to a physician’s office or an emergency room. Sometimes, such adverse reactions lead to hospitalization or even death. A patient’s first line of defense against medication hazards is the label on the drug’s container that provides information about the drug and how it should be taken. Yet research shows that nearly half of all patients have trouble understanding label instructions, either because of some type of literacy limitation or because the labels are poorly presented.

… research shows that nearly half of all patients have trouble understanding label instructions, either because of some type of literacy limitation or because the labels are poorly presented.

The IOM’s Roundtable on Health Literacy examined this safety issue in a workshop that brought together a diverse array of participants, including representatives from government, the pharmacy field, the health care community, the research enterprise, and the public, among others. Standardizing Medication Labels: Confusing Patients Less: Workshop Summary (2008) surveys what is known about how medication container labeling affects patient safety and describes participants’ various suggestions for fixing the problem.

Many patients do not understand current drug labels, but the best way to improve comprehension of medication instructions is unclear. Experts differ in their judgments about exactly what information should be included on a drug label and how that information should be presented. Although there have been some tests of various types of labels, workshop participants concluded that more research is needed to find answers that are both broader and more precise. There is also disagreement about whether regulation or a voluntary approach will best achieve label standardization, with some participants

Patient Misunderstanding of Medication Instructions

|

Dosage Instruction |

Patient Interpretation |

|

Take one teaspoonful by mouth three times daily |

Take three teaspoons daily Take three tablespoons every day Drink it three times a day |

|

Take one tablet by mouth twice daily for 7 days |

Take two pills a day Take it for 7 days Take one every day for a week I’d take a pill every day for a week |

|

Take two tablets by mouth twice daily |

Take it every 8 hours Take it every day Take one every 12 hours |

|

SOURCE: Standardizing Medication Labels: Confusing Patients Less: Workshop Summary, p. 15. |

|

favoring each approach and arguing that the other has not been proven successful.

In providing a possible way forward, the report offers a list of questions for an expanded research program. What are the mechanisms by which standardization can be achieved? What would the process look like? What are the costs of standardizing? What level of evidence is needed to introduce a best practice? At the same time, care must be taken to ensure that steps to promote label standards do not detract from other efforts, such as education of both patients and physicians in matters of drug safety, that are needed to reduce medication errors.

Reducing environmental and foodborne threats

Many public health concerns stem from some type of agent that humans release into the environment. This release may result from the activities of society—for example, from industries that emit chemical pollutants—or from the actions of individuals, as in the instance of cigarette smoking. In either case, the public has an interest in better understanding and eliminating all such hazards.

Reviewing Great Lakes pollution studies

The Great Lakes are magnificent—and environmentally critical—resources for both the United States and Canada. But many sections of the lakes are

contaminated with a variety of potentially hazardous pollutants. In 1972, the two nations signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement to restore and maintain the lakes’ chemical, physical, and biological integrity. Under the agreement, the International Joint Commission monitors and assesses the nations’ activities, including efforts to protect human health from contaminants. In 2001, the commission asked the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), part of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to evaluate the public health implications of hazardous materials present in U.S. portions of the lakes. (The commission also has worked with Health Canada to document conditions in Canadian waters.)

After a first unsuccessful attempt, the ATSDR produced a draft report in 2007. Even then, registry officials had concerns about the methods used and the conclusions drawn in the draft, and the registry released a revised draft report in 2008. This further revision attracted criticism of its scientific integrity, however, and the CDC asked the IOM to conduct an independent study. Review of the ATSDR’s Great Lakes Report Drafts: Letter Report (2008) concludes that both drafts have shortcomings that diminish

U.S. and Binational Great Lakes Areas of Concern.

NOTE: AOCs = Areas of Concern.

SOURCE: Review of the ATSDR’s Great Lakes Report Drafts: Letter Report, p. 33.

their scientific quality and limit their usefulness in determining whether health risks might be associated with living near the lakes. The report itemizes a number of faults—often involving data selection—and explains their adverse consequences. Many of the problems appear to stem from the lack of a clear statement of objectives and an approach to reach those aims.

The report suggests ways to approach similar tasks in the future. Such projects should begin by identifying the research questions to be answered or the tasks to be undertaken, and then should develop and document a detailed approach to answering those research questions. The group undertaking the project also should seek out other entities for partnering, such as federal agencies or state governments, as early in the process as possible.

Improving food safety

In support of strengthening the U.S. food safety system, IOM worked with the Division of Earth and Life Studies to help the U.S. Department of Agriculture to improve its risk-based inspection system. Additionally, a congressionally mandated review of the Food and Drug Administration’s role in ensuring safe food is underway and will be completed by summer 2010.

Improving emergency preparedness

In today’s world, the United States must be prepared to respond to a variety of hazards, both natural events and deliberate actions taken by other nations or terrorist groups. Ensuring a high degree of preparedness remains a never-ending concern. The IOM recognizes that preparing for emergencies and disasters is crucial to protecting the public’s health. The organization has devoted many resources to helping federal agencies prepare for national emergencies that may arise, with particular focus during the past few years on emerging diseases.

In 2008–2009, the IOM held a workshop on the capacity of the health care system to treat an affected population in the case of a nuclear event; published a report discussing how the global health community can strengthen surveillance and response to emerging zoonotic diseases; and will release late in the year another report that evaluates the Department of Homeland Security’s BioWatch program, which is intended to detect airborne biological threats. Three previous IOM reports provide insights into how government might respond to an outbreak of pandemic influenza

|

Key Elements of Preparedness A prepared community is one that develops, maintains, and uses a realistic preparedness plan that is integrated with routine practices and has the following components: Preplanned and coordinated rapid-response capability

|

Expert and fully staffed workforce

Accountability and quality improvement

SOURCE: Research Priorities in Emergency Preparedness and Response for Public Health Systems: A Letter Report, p. 11. |

or other infectious disease threats. These reports speak to the use of face masks and other personal protective equipment in health care settings. All emphasize the vital importance of meeting the needs of the health care workers and other front-line personnel who provide care for others during an influenza pandemic.

As part of a national effort to ensure security, Congress in 2006 enacted the Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act, which called for refocusing the research priorities of the network of Centers for Public Health Preparedness now operating at 27 accredited schools of public health nationwide. The federal government had created the centers in 1999 to provide expanded expertise to strengthen the nation’s emergency response systems, and the new law both refined and expanded that charge.

To help with this restructuring, the agency that oversees the centers, the Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response (COTPER), which is part of the CDC, asked the IOM to develop a research agenda that can be carried out over the next 3 to 5 years. Research Priorities in Emergency Preparedness and Response for Public Health Systems: A Letter Report (2008) proposes that the centers give priority to four general areas. These include research (1) to design and implement emergency preparedness training and for translating the results into public use, (2) to communicate accurate information in a timely manner to diverse audiences, (3) to create sustainable community-based preparedness systems, and (4) to generate improved criteria and metrics for evaluating the performance of public health emergency response systems.

Less than a month after the IOM released its report, COTPER issued a request for applications for research grants that incorporated almost verbatim the report’s findings and recommendations. COTPER expects to award nearly $9 million to projects that “investigate the structure, capabilities, and performance of public health systems for preparedness and emergency response activities.”