7

Strategies That Work

INTRODUCTION

In response to the stresses induced by rapidly escalating healthcare costs, discussions about a multitude of strategies to lower spending have engaged the leadership of hospitals and clinics, health plans, pharmaceutical and device companies, economists, academics, and elected officials. Suggestions have focused on such varied reforms as bundled payments, accountable care organizations, regulation of medication prices, quality transparency, tort reform, administrative simplification, and structured discharge planning and follow-up (Antos, 2009; Berenson et al., 2009; Clancy, 2009; The Commonwealth Fund, 2009; Healthcare Administration Simplification Coalition, 2009; Mello and Brennan, 2009; UnitedHealth Group, 2009; U.S. Congress, 2008). The goal of the second workshop in the series was, following a brief review of the estimates of excess costs presented at the first workshop, to explore the evidence and ideas behind these strategies as possible solutions to improving the delivery and efficiency of the U.S. healthcare system.

In the opening session, a review of the May workshop engaged the analytics presented on the amount of potentially controllable waste and inefficiency in healthcare spending. These estimates focused on five broad areas: unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excess administrative costs, prices that are too high, and missed prevention opportunities. Focusing on these estimates, Dana Goldman of RAND, Eric Jensen of McKinsey Global Institute, Jonathan S. Skinner of Dartmouth College, Len Nichols of the New American Foundation, and Robert D. Reischauer of the Urban

Institute offered reflections on the estimates and the relative contributions from among the five areas, the considerations needed to assure accuracy and utility of the numbers, and the implications for the reform process. The moderator summarized the written comments of the first three, and Nichols and Reischauer addressed participants directly.

The panelists frequently converged in their comments, specifically highlighting the ideas of: dimensionalities, including the suggestions to additionally consider the nuances of identifying concrete examples of inefficiency, the varying components of pricing, the benefits of some administrative activities, and the application of such estimates to the reform process and clinical care; technical challenges, including limitations of the data and consideration of the circumstances of individual localities when implementing policy changes; and opportunities, including obesity as an area of underinvestment in prevention and the development of further refinements in the analytics that facilitate action by policy makers.

Laying the groundwork for subsequent presentations with his keynote address for the second workshop, Glenn Steele, Jr., draws on his experience leading Geisinger Health System to provide real-life examples of effective strategies to bend the cost curve. Highlighting how Geisinger has leveraged its position as both provider and payer to innovate within the current delivery system without developing new operational and financial problems, he describes their pioneering work with bundled payments for cardiac surgery, which has yielded significant improvements in the delivery of evidence-based care and decreased rehospitalizations within 30 days by 44 percent. With a focus on the high-use chronic disease population, Steele relays that their care management initiative has reduced readmission rates among the targeted population by nearly 30 percent within a year and decreased total medical costs by 4 percent—a return on investment of 250 percent. He also describes the positive externalities arising from their innovations, citing how the teachers in Danville, Pennsylvania, received an average raise of $7,000 because of Geisinger’s ability to decrease health insurance costs. Identifying Geisinger’s organization, local marketplace, financial health and planning, and the sociology of its catchment area as key elements of their local environment, he characterizes the success of their interventions in acute and chronic care as steeped in their ability to innovate, experiment, and learn “on the fly.”

In a complementary presentation, Gerard F. Anderson discusses potentially transplantable initiatives and approaches used by other nations to achieve the twin goals of expenditure control and outcomes improvement, specifically focusing on payment reforms, no-fault malpractice insurance, and care coordination. Noting that specialists in the United States earn up to 300 percent more than those in other countries, that prices for branded drugs cost up to twice as much, and that hospitals stays are up to

200 percent more expensive, he suggests that cost control mechanisms in other nations such as Germany have helped control spending growth and could yield significant savings if applied here. With respect to differences in medical liability costs, Anderson relays that while Canada and the United Kingdom have similar types of malpractice insurance as the United States and similar rates of litigation and award levels, the no fault malpractice model in New Zealand has resulted in lower premiums and fewer lawsuits. Finally, he also discusses Germany’s focus on care coordination for individuals with chronic conditions and their provider, payer and consumer incentives, which together have lead to decreasing rates of hospitalizations for this population.

REVISITING “UNDERSTANDING THE TARGETS”

Translating Estimates into Policy

The commenters spoke of the opportunities in terms of the costs and potential savings discussed at the May workshop, as well as the very intuitive nature of many of the interventions discussed. Many of the ideas, such as standardizing billing software reconciliation and administrative simplification, appear obvious and straightforward, said Nichols. He also emphasized the significant technical challenge in the implementation of these strategies. He additionally spoke of the importance of specificity in defining the processes and levers of execution for those savings, particularly in terms of application and dissemination—critical elements of the policy discussion. Building on this idea, Reischauer identified the potential savings in preference-sensitive care, such as patient education and shared decision making, as an area of “low-hanging fruit” because of the ease of envisioning effective and politically sustainable policies that could engender savings in this area. Finally, Nichols encouraged consideration of policies designed to invoke change yet simultaneously deal with political barriers as a method of finessing strategies to lower costs and improve outcomes in a manner that could be applied from rural Pennsylvania to throughout the country.

Reflections on the Analytics

Reischauer continued the discussion by focusing on specific considerations for the major areas covered during the first workshop. While additional analyses will be required to refine the analytics, he stated that the comparison between the best and worst performers in terms of quality and cost superficially appeared to be an intuitively sound method for determining the cost of unnecessary services. The moderator, J. Michael McGinnis, summarizing the comments of Goldman, Jensen, and Nichols, also reported

that, while analyses of regional variations could identify spending outliers, further insights into the subtleties in spending patterns, such as the components of expenditures driven by inappropriate compared to discretionary care, will require further investigation.

In this category of savings opportunities, Reischauer suggested that further research should include identifying what excess services might be provided even by the “best” providers, as well as clearly describing what truly suboptimal use of services might be. Another focus in determining the scope of unnecessary services was Medicare. However, Reischauer explained that care must be taken in generalizing the findings in a Medicare population to the private healthcare sector. In addition, geographic differences likely are significant in Medicare, he asserted. As an example, he discussed the possibility that, in areas where Medicare is a relatively good payer—in terms of payment level and ease of payment—relative to private insurers, the incentives are to provide more services to Medicare beneficiaries. Where the inverse is true, incentives drive in the opposite direction. As such, the methods of maximizing the impact of strategies to lower costs and improve outcomes will require consideration of the unique milieu in individual markets.

Reischauer discussed how high administrative costs, some portion of which has been defined as excess administrative costs, are the result of the structure of our healthcare system. Because the American public values choice, quality, and innovation—all of which adds to the costs of administration—he urged careful consideration of the benefits accrued by such spending against the costs and drawbacks. The panelists further identified how some administrative activities are duplicative and redundant while others support safety initiatives, quality improvement efforts, and fraud prevention. Lacking financial pressure and inelastic demand, Reischauer identified these areas as potential policy targets to create stronger incentives for providers and payers to maximize their administrative efficiencies.

In terms of prices, Reischauer defined four dimensions to the issue: (1) some payers pay more than necessary; (2) the overall level of prices are too high and allow for too much profit; (3) controlling the growth rate of prices may not yield significant savings; and (4) prices for new medical products and services fail to decrease over time as they do in most hightech markets. He identified a need to address these components of pricing singularly in order to facilitate translation of the estimates into policy recommendations. McGinnis further discussed how the panelists suggested that shifting the focus from the selling price of medical products to the price per unit of health might also yield insights.

McGinnis also mentioned how the commenters discussed how underinvestment in prevention stems partly from frequent turnover in health insurance coverage, where short tenures in multiple private insurance systems fail

to create incentives for payers to invest in prevention. The panelists argued that current incentives and metrics have not yet captured the importance of preventive care. Considering areas for long-term gains, the commenters identified the need for focus on obesity prevention, citing national trends and projected expenditures resulting from obesity and its health sequelae.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The panelists commented that the work engaged represented an excellent starting point, especially considering the methodological challenges and data limitations. To maximize their utility in the reform discussions, the panelists emphasized the need for continued work and refinement of the estimates, with a focus on the development of further actionable opportunities for policy makers to consider.

STRATEGIES THAT WORK AND HOW TO GET THERE

Glenn Steele, Jr., M.D., Ph.D.

Geisinger Health System

Over the past decade, the Geisinger Health System has been able to leverage its market share, its continuum of care, and its strong partnerships with payers and providers throughout Pennsylvania to innovate in ways that produce real cost savings and positive health outcomes among those consumers with the highest disease burdens. The key to success at Geisinger has been a thoughtful plan to experiment and “hedge” its innovations so as to find solutions that drive shared health goals without sacrificing the financial or operational health of the system. It is our belief that, while Geisinger’s environment may contain some unique elements, this milieu of innovation and experimentation is replicable and scalable beyond our experience.

Hedging: Creating Opportunities to Innovate

The Geisinger Health System has been uniquely positioned over the past decade to innovate for a number of reasons, but primarily because we have been able to take different approaches with the 30 percent of our patient population where we are both provider and payer. This “hedging” strategy has allowed us to innovate without developing new operational and financial problems, as other health systems have experienced when they have experimented with adjusting the perverse incentive structures in health care today. Geisinger has also been well positioned to expand its innovative practices, because for the 70 percent of our patients from payers

like Capital Blue Cross, Northeast Blue Cross, Coventry, and Highmark, our market share, credibility, and capacity for continuum of care afford us the opportunity to negotiate great rates and partner in ways that support some of these innovations. As a result, Geisinger has been able to experiment and get results much more quickly than some other health plans in the marketplace today.

ProvenCare for Acute Episodic Care

Geisinger started its innovation on acute episodic care by focusing on elective coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries. Here we sought to identify high-volume diagnosis-related groups, determine best practices, deliver evidence-based care, and create a global, single-fee payment system for acute episodic care. As defined by Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4), our outcomes from CABGs were already extraordinarily good, with low mortality and morbidity rates. The goal was to make these good outcomes even better by applying a complete reengineering process to eliminate unjustified clinical variation.

At the center of this effort was the definition of specific guidelines for care related to CABGs based on the 2004 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for CABG surgery. Physicians throughout our system reviewed these guidelines carefully along with the evidence in the field, which built the necessary buy-in to adopt approximately 40 best practice components of care. All were either evidence- or consensus-based and thought or shown individually to be associated with best outcomes. Questions such as “When do we start and stop the antibiotic?” and “What should the patient’s temperature be when the patient leaves the operating room and goes to the recovery room?” were considered. All these care components had never previously been incorporated into a completely reengineered clinical care process; this was the opportunity for Geisinger to “experiment.” Interestingly, as we started ProvenCare, we found that, even though we already had great outcomes and good value (by the PHC4 data), we were only employing all of these best practices just over half of the time.

We also reengineered our payment structure by developing a single price that included a significant discount on the historical complication charges when we looked over the 2 years prior to starting ProvenCare. While this payment structure seemed risky, we were able to move ahead as both provider and payer for our targeted 30 percent patient population.

Today, most of our CABG care is 100 percent compliant with our guidelines. Health outcomes have improved across the board (Table 7-1). Not only has mortality and morbidity dropped even more, but costs have also decreased. Our total insurance cost for CABG had already been rela-

TABLE 7-1 Quality/Value: Clinical Outcomes (18 months)

tively low. But since the introduction of this project, costs have fallen even more.

ProvenCare Chronic Disease Optimization

Extending the lessons and innovation of our work with acute episodic care, Geisinger has also looked at optimizing care for chronic diseases, such as coronary vascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and preventive care. The major difference is, in addition to relative-value unit payments, up to 20 percent of total cash compensation is based on performance metrics.

The results have been somewhat mixed. For type 2 diabetes, we identified nine performance criteria or quality targets. When we started this work, only 2.4 percent of patients had all nine of these best practice goals achieved. However, as we continued to focus on this work, our results have improved. In 2007, the number rose to 10 percent. In 2008, the incidence

rose to 12 percent, with the rate leveling off at approximately 11 percent in March 2009.

Despite these improvements, we have not yet seen demonstrated improvement in outcomes. Diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic vasculopathy have not been noted to decrease over this time. Nor has the hospitalization rate for this group decreased. The commitment to this particular kind of performance-based payment system may yet prove effective, but at least we have modeled a way to shift the perverse piece rate payment incentives of the healthcare system to one that is aligned with what is thought to be better care.

ProvenHealth Navigator

Lastly, in the case of ProvenHealth Navigator, we have worked collaboratively with payers, community clinics, and other providers to develop a targeted solution focused on the highest-use chronic disease patient population. These are typically 75-year-old patients with 4 or 5 chronic conditions who are taking 20 medications a day. We wanted to see if we could decrease hospitalizations and rehospitalizations by improving home-based or community-based chronic disease management.

Our community practice leadership and our insurance company, Geisinger Health Plan, together developed a program of a series of patient-centric aims: patient engagement, physician endorsement and oversight of the care continuum, individualized care plans, automated assessment and triage, and coordinated care. Geisinger’s insurance company supported nurses who were embedded in our community practice sites. Each nurse was responsible for 125-150 of the sickest, highest-using patients. These nurses were in essence the first triage contact regarding anything that occurred with these patients or their caregivers. Additionally, we had a commitment to complete, accurate, and searchable data and registries to facilitate the continuum of care.

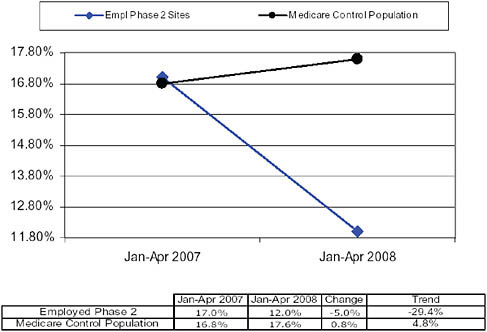

Initial results have been remarkable; readmission rates among the targeted population dropped by nearly 30 percent within a year (Figure 7-1), and total medical costs have decreased 4 percent—a return on investment to the insurance company of an astounding 250 percent. Today, the program is in its third phase with about 35,000 Medicare patients and 30,000 commercial patients. Already, we see similar results emerging in this larger cohort.

Drivers of Success

The success of ProvenCare has been a function of four factors—anatomy, market, financial health and planning, and sociology—discussed in the following sections. However, one of the major messages from our

FIGURE 7-1 Readmission rate.

experience is that these successes need not be specific to Geisinger or even to integrated health systems like Geisinger. We believe that what has made this work so powerful is that it included non-Geisinger physicians as well as partners who do not have electronic health records.

Anatomy

Geisinger employs a continuum of care model that includes the full range of healthcare services from primary care to specialty and subspecialty care. Furthermore, this system has involved not just its own doctors and medical staff, but non-Geisinger physicians, casting a wider net and expanding the opportunities. Significantly, we have been electronically connected since 1995, covering everything from primary care to specialty and subspecialty care. In all of the cases discussed here, we have worked hard to align incentives and to work in partnership with payers and providers to define those goals.

Market

The Geisinger Health System has a large market across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania where it encompasses both the insurance and

provider side. Furthermore, the demography of the coverage area is very stable, which includes a population of aging, poor residents, who carry one of the largest disease burdens in the country.

Financial Health and Planning

Having sound finances—a strong balance sheet and sound operations—has been critical to sustaining these innovations. All of this work involved risk taking, so planning for those risks and “hedging” by targeting the innovations has been critical.

Sociology

Although Geisinger represents an integrated health system, the lack of that financial structure and culture does not have to be a barrier to these kinds of changes. We have found significant interest by all physicians—even those in nonintegrated systems—in experimenting with improving outcomes and lowering excess costs. The power of professionalism and good intention in medicine has been a key driver. Along the same lines, the patient-centric paradigm has facilitated much of the ProvenCare model. Thinking about how to get care out to patients instead of how to bring patients into our hospitals is an enormous advantage. That paradigm is intrinsic to how we frame conversations and build partnerships with all the stakeholders.

Conclusion

As we share these successes with the broader medical community and as the national conversation continues about reforming the healthcare delivery system, ProvenCare and Geisinger provide a useful lesson in the power of experimentation. What Geisinger has been able to do is to learn “on the fly.” Within a short time we have found some programs and initiatives that appear to work well and others that need continued tinkering. Our experience has also shown us that continued attention and devotion to improvement is needed to maintain any gains achieved. Recidivism and inertia remain the baseline!

The nation will need a great deal more innovation to “bend the curve” in healthcare costs. Not everything will work the first time around. Yet we have drawn this major lesson from our initiatives and efforts: many of the challenges facing our healthcare system today can be addressed directly with thoughtful planning and goals, creative experimentation, and considerable flexibility.

INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS AT COST CONTAINMENT

Gerard F. Anderson, Ph.D.

Johns Hopkins University

The 30 industrialized countries that form the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are all interested in controlling healthcare costs. Their varied approaches to healthcare system design and successful cost control should inform the United States as it faces its own challenges with cost containment. The United States spends over twice as much per capita and 50 percent more of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care than these other countries. Even so, the health outcomes in these other countries are often better than the outcomes in the United States, demonstrating that it is possible to control costs without sacrificing good outcomes. While many examples of successful cost containment initiatives exist internationally, this paper focuses on three areas: (1) payment reforms; (2) no-fault malpractice insurance; and (3) care coordination.

Payment Reforms

Most of the attention in the United States has been on controlling the volume of health care. However, international comparisons suggest that more attention should be given to prices. Compared to other OECD countries, the prices for certain medical goods and services are significantly higher in the United States (Reinhardt et al., 2002). Consider the following examples:

-

Prices for branded drugs are 25 to 100 percent higher.

-

Specialists earn 100 to 200 percent more than specialists in other countries.

-

Hospital stays are 100 to 200 percent more expensive than in other countries.

At the same time, the quantity of services is approximately equivalent. There are similar numbers of doctors and doctor visits per capita, slightly fewer hospital beds and hospital days per capita in the United States, and about the same number of drugs prescribed per capita. Notably, there are higher levels of some procedures and tests performed in the United States although not in all cases. All of this has led to the general observation that prices are a major driver of out-of-control costs when comparing the expenditures in the United States to those in other industrialized countries (Anderson et al., 2003).

Prices for Medications

Drug prices for brand-name drugs are controlled in other countries using a variety of systems, including value-based purchasing (Sweden), formularies (Australia), comparative effectiveness (United Kingdom [UK]), efficiency frontiers (Germany), and reference pricing (many European countries) (Wagner and McCarthy, 2004). The United States could adopt one of these approaches or adopt a variant of one of these approaches. We have already started down the road of comparative effectiveness, but the current legislation does not include costs as a component of the analysis. This would need to change in order to be able to obtain lower prices for brand-name drugs. All the other countries that conduct comparative effectiveness research include costs in their calculations. Each system is different, and each provides different incentives to substitute generic for brand-name drugs and different incentives for drug companies to innovate. The programs are generally successful at controlling drug prices, and the result is that drug prices are 25 to 100 percent lower for brand-name drugs (Anderson et al., 2004). There seems to be little difference in prices for generic drugs. Because of the mix of brand and generic drugs in the United States, if prices of brand-name drugs in the United States were made equal to international prices, total expenditures for drugs in the United States would drop by 25 percent. Even though a commonly cited concern is that lower prices could lead to less resources being allocated to research and development, drug companies only spend approximately 17 percent of their revenues on research and development. It is unclear how much they would actually reduce research and development and how much they would reduce marketing and other spending.

Physician Incomes

Specialists in the United States earn 200 to 300 percent more than specialists in other OECD countries, while the incomes for generalists are much more comparable (Reinhardt et al., 2004). Most countries use fee schedules to pay physicians similar to the Medicare resource-based relative-value system. The major difference in other countries is that the fee schedules are not weighted toward specialty medicine; in fact, in many northern European countries, the generalist physician is paid a higher income than the specialist. In the UK, for example, the generalist has control over access to the specialty physician and typically earns a higher income than the specialist. In Denmark, the ophthalmologists who diagnose the patients are paid higher incomes than the ophthalmologist who performs the surgery. If the United States were to adopt the system of paying specialists the same rates as generalists, then expenditures for physician services would drop

by 60 percent. Clearly, this change could not happen overnight, and it may be necessary to increase the income of generalists in order to continue to attract the best and brightest into medicine. It is, however, something to consider when revising the resource-based relative-value scale schedule. One possibility is to examine the relative weights used in other countries as a model for revising the resource-based relative-value scale.

Payments for Hospital Care

Hospitals in the United States are often paid as much for the first day of a hospital stay as hospitals in other countries are paid for the entire visit. While we do not have data to completely understand the reasons for all of the difference, the three main reasons appear to be: (1) greater administrative expenses in the United States dealing with a multipayer system, (2) much higher salaries paid to administrators and hospital staff, and (3) greater use of medical technology.

Hospital managers are fond of comparing their costs and performance to other hospitals in the United States. A study tour comparing the costs and performance in other countries could also be enlightening. Other countries have adopted capital controls (Canada) and an all-payer rate setting for hospitals (Germany), and these have been successful in controlling costs. In Canada capital costs are allocated directly by the provincial governments. In Germany all sickness funds pay the same rates to the hospital and the rate is negotiated between all the sickness funds and the individual hospital. If U.S. hospital costs could approximate the costs in other industrialized countries, then hospital expenditures could be reduced by 50 percent. The first step in this process would be a detailed comparison of the costs of hospital care in the United States and other countries. Is the cost difference due to different use of medical technology, greater use of nursing and other services, higher wages, or some other factor? Once the difference has been identified, it would be possible to see the changes in cost structure needed in the United States. Clearly, this would need to be phased in over many years. It is surprising, however, how much more expensive U.S. hospitals are compared to hospitals in other countries.

In summary, payment reforms in the areas of drug spending, specialty physician compensation, and hospital-care spending could yield significant savings if we replicate the cost controls found in other OECD countries.

No-Fault Malpractice Insurance

One of the major concerns of U.S. physicians is malpractice litigation (Mello et al., 2003). As a response, many physicians report that they practice some form of defensive medicine. While empirical studies are unclear

on exactly how much malpractice premiums or defensive medicine adds to the cost of U.S. health care, it remains a major public policy concern; yet, once again, there are alternative policy responses found in OECD peer countries (Kessler and McClellan, 2002).

Countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom have a similar type of malpractice insurance and, much to the surprise of many U.S. physicians and policy makers, they also have similar rates of litigation and similar levels of awards. On the other hand, New Zealand has adopted nofault malpractice insurance and has significantly lower rates of malpractice claims, lower and more consistent monetary awards, greater cooperation in identifying and fixing medical errors, and much lower legal expenses. In spite of a much easier system to bring a claim, it is also surprising that in New Zealand relatively few people actually bring a claim. The best estimate is that only 1 in 30 potential claimants actually sues (Bismark and Paterson, 2006).

Adoption of no-fault insurance would have multiple benefits. There would be lower malpractice premiums and less defensive medicine. There would be lower legal costs and fewer barriers to filing a malpractice claim. And perhaps the greatest benefit would be a greater willingness to share information about medical errors, which can lead to more effective and targeted interventions to prevent them.

Care Coordination

In the United States most disease management and care coordination initiatives, especially in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, have demonstrated little improvement in controlling costs or improving outcomes. This is especially important for the Medicare program where two-thirds of all Medicare spending is on behalf of beneficiaries with five or more chronic conditions and where outcomes are especially poor (Anderson, 2005).

Germany has taken a somewhat different approach to care coordination and disease management. First, it pays the sickness funds (health insurers) a much higher rate for individuals with chronic conditions. In the United States the current risk adjustment systems used by Medicare and other insurers overpay for the healthy and underpay for those with multiple chronic conditions (Kautter et al., 2008). In Germany the payment bias is reversed with the sickest patients getting the most money. This different orientation provides an incentive for German sickness funds to focus on the needs of people with multiple chronic conditions. Second, the sickness funds create separate programs for people with chronic conditions. This allows these programs to specialize in people with chronic conditions. Many U.S. health insurers try to integrate persons with chronic conditions into the traditional health insurance system. In the United States there are special

needs plans but these are generally small and cover only a small portion of the chronically ill. Third, there are strong financial incentives for German physicians to specialize in the care for people with chronic conditions. The payment rates are significantly higher and compensate the physicians for the additional workload these patients require. The United States is debating how to pay for such things as care coordination while Germany has been doing this for several years. Fourth, people with chronic conditions are given financial incentives to enroll.

The bottom line is that more than half of all Germans with a chronic condition enroll in one of these programs and enrollment is disproportionately high for people with multiple and complex chronic conditions. It is still too early to tell how much the program is actually saving, although preliminary estimates show significant declines in hospitalization rates, suggesting high returns of value from the healthcare services and significant cost savings.

Summary

The United States spends twice as much per capita on health care than its peers, and yet the United States does not get any better outcomes—in some cases, it actually gets worse outcomes. A great deal can be gleaned by looking to the practices and policies of these peer countries, and in this paper, three specific areas are considered as a beginning: (1) paying international prices for goods and services, (2) adopting no-fault malpractice insurance, and (3) creating separate programs for people with multiple chronic conditions. In just these three examples, the United States can learn quite a bit about lowering costs at margins from 25 to 300 percent of cost while also enhancing value for patients.

REFERENCES

Anderson, G. F. 2005. Medicare and chronic conditions. New England Journal of Medicine 353(3):305-309.

Anderson, G. F., U. E. Reinhardt, P. S. Hussey, and V. Petrosyan. 2003. It’s the prices, stupid: Why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Affairs (Millwood) 22(3):89-105.

Anderson, G. F., D. G. Shea, P. S. Hussey, S. Keyhani, and L. Zephyrin. 2004. Doughnut holes and price controls. Health Affairs (Millwood) Suppl web exclusives: W4-396-404.

Antos, J. 2009. Bending the curve: Effective steps to address long-term health care spending growth. http://www.brookings.edu/reports/2009/0901_btc.aspx (accessed October 8, 2009).

Berenson, R., J. Holahan, L. Blumberg, R. Bovbjerg, T. Waidmann, and A. Cook. 2009. How we can pay for health care reform. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Bismark, M., and R. Paterson. 2006. No-fault compensation in New Zealand: Harmonizing injury compensation, provider accountability, and patient safety. Health Affairs (Millwood) 25(1):278-283.

Casale, A. S., R. A. Paulus, M. J. Selna, M. C. Doll, A. E. Bothe, Jr., K. E. McKinley, S. A. Berry, D. E. Davis, R. J. Gilfillan, B. H. Hamory, and G. D. Steele, Jr. 2007. “Proven-Caresm”: A provider-driven pay-for-performance program for acute episodic cardiac surgical care. Annals of Surgery 246(4):613-621; discussion 621-613.

Clancy, C. 2009. Comparative effectiveness research. The Healthcare imperative: Lowering costs and improving outcomes workshop, July 16-18, Washington, DC.

The Commonwealth Fund. 2009. The path to a high-performance U.S. health care system: A 2020 vision and the policies to pave the way. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/Feb/The-Path-to-a-High-Performance-US-Health-System.aspx (accessed August 26, 2009).

Healthcare Administration Simplification Coalition. 2009. Bringing better value: Recommendations to address the costs and causes of administrative complexity in the nation’s health care system. http://www.simplifyhealthcare.org/repository/Documents/HASC-Report-20090717.pdf (accessed October 1, 2009).

Kautter, J., M. Ingber, and G. C. Pope. 2008. Medicare risk adjustment for the frail elderly. Health Care Financing Review 30(2):83-93.

Kessler, D., and M. McClellan. 2002. Malpractice law and health care reform: Optimal liability policy in an era of managed care. Journal of Public Economics 84(2):175-197.

Mello, M. M., and T. A. Brennan. 2009. The role of medical liability reform in federal health care reform. New England Journal of Medicine 361(1):1-3.

Mello, M. M., D. M. Studdert, and T. A. Brennan. 2003. The new medical malpractice crisis. New England Journal of Medicine 348(23):2281-2284.

Reinhardt, U. E., P. S. Hussey, and G. F. Anderson. 2002. Cross-national comparisons of health systems using OECD data, 1999. Health Affairs (Millwood) 21(3):169-181.

Reinhardt, U. E., P. S. Hussey, and G. F. Anderson. 2004. U.S. health care spending in an international context. Health Affairs (Millwood) 23(3):10-25.

UnitedHealth Group. 2009. Federal health care cost containment—How in practice can it be done? (Working Paper #1). Minneapolis, MN: UnitedHealth Group.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. 2008. Medicare Part D: Drug pricing and manufacturer windfalls. http://oversight.house.gov/documents/20080724101850.pdf (accessed September 10, 2009).

Wagner, J., and E. McCarthy. 2004. International differences in drug prices. Annual Review of Public Health 25:475-495.