11

Payment and Payer-Based Strategies

INTRODUCTION

To obtain better value for investments made in health care, significant discussion has emerged on how best to align economic and health incentives to achieve these goals (Dudley et al., 2007; IOM, 2007; Orszag and Ellis, 2007). Focusing on providers, attention has turned to the current fee-for-service reimbursement model. By placing the incentives on volume over value, fee-for-service fails to create incentives for preventive care and care coordination among providers (MedPAC, 2008; Miller, 2007). As physician practices spend an average of 3 hours a week interacting with health plans at a national cost of $23 billion to $31 billion a year, the administrative complexity created by multiple documentation requirements to varying billing, precertification, and credentialing forms takes time away from clinical care (Casalino et al., 2009). Failure to clearly differentiate the value and benefits of alternative providers, treatments, and health plans obfuscates the signals to consumers (Chernew et al., 2007). The papers in this chapter cover a range of strategies targeting the payment and payer systems as sources of opportunities for lowering costs and improving outcomes, underscoring the importance of streamlined and harmonized health insurance regulation, administrative simplification and consistency, and payment redesign to focus incentives on results and value.

Harold D. Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform reviews the broader evidence base of payment reform’s impact on costs and quality and provides a conceptual framework for possible payment policies. Building on Miller’s comments and recommendations on

strategies for transitioning to more value-based payment structures, Amita Rastogi of Bridges to Excellence discusses the promising effects of the PROMETHEUS (Provider payment Reform for Outcomes, Margins, Evidence, Transparency, Hassle-reduction, Excellence, Understandability, and Sustainability) payment system, based on a fee-for-episode system. She focuses in particular on the allowance in the PROMETHEUS system for potentially avoidable complications, which is designed to encourage reduction in such complications by at least 50 percent. Translating their estimates to the national level, she reports a potential cost savings of $165 billion nationally from reducing potentially avoidable complications in 13 medical conditions in the commercially insured population.

David R. Riemer of the Community Advocates Public Policy Institute highlights health insurance exchanges as a promising practice for introducing managed competition into the insurance market. Drawing on the lessons learned from one of the nation’s most long-lasting and successful exchanges, operated by the Wisconsin State Employee Health Plan in Dane County, he suggests that three conditions must be in place to maximize the ability of health insurance exchanges in lowering costs: the pool of potential enrollees should have an average or near-average risk profile; the pool of enrollees must be at least 20 percent of the population; and the enrollees must have clear financial incentives for selecting health insurance plans that have the lowest risk-adjusted bids.

Turning to consumer incentives, Niteesh K. Choudhry from Harvard University discusses value-based insurance design, focusing on the potential impact of tiering copayments for medications based on evidence-based value. He explains that, with insurance copayments set in a one-size-fits-all style, copayments for essential, high-value services are often set too high, and their resultant underuse leads to missed opportunities to prevent and treat morbid and expensive diseases while copayments for nonessential, low-value services are sometimes not set high enough to minimize their unnecessary use. Although the evidence base is limited, existing studies suggest that value-based insurance design for five chronic conditions may reduce costs by 1 to 6 percent, the equivalent of more than $2 billion annually. However, he cautions that these preliminary estimates, by necessity, aggregate groups of conditions into single disease categories, such as “heart disease,” do not account for patients with more than one related condition, and do not distinguish between the impact on patients of different disease severities. In a complementary discussion, Lisa Carrara of Aetna describes a variant of value-based insurance design with a discussion of tiered provider networks and consumer-directed health plans. Based on the experience of the Aetna Aexcel network of designating providers based on clinical quality and cost efficiency, she estimates that up to a 3 to 4 percent reduction in first year claims could be realized by customers if all Aetna patients demonstrated a 90 percent utilization of Aexcel-designated physicians.

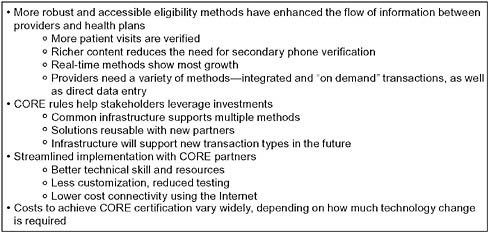

Both Robin J. Thomashauer from the Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare (CAQH) and David S. Wichmann from UnitedHealth Group conclude this session by discussing different approaches to administrative simplification. Thomashauer describes CAQH’s work in driving payer collaboration and process consolidation through multistakeholder initiatives—the Committee on Operating Rules for Information Exchange (CORE) and the Universal Provider Datasource (UPD). Through development of standardized operating rules to facilitate administrative data exchange and promote interoperability, she relays that industry-wide adoption of CORE rules could save $3 billion over the next 3 years. Citing the success of this cross-industry, public–private collaboration, Thomashauer outlines the need for continued collaboration focused on both short- and long-term goals, coupled with appropriate policy support through the federal government. Meanwhile, Wichmann outlines how the use of current technology could improve payment speed and accuracy and streamline provider credentialing, privileging, and quality designation processes, yielding savings of $332 billion over the next decade. To achieve these savings and improve healthcare delivery, he urges shared, consistent action across all payers—commercial and governmental—in partnership with physicians and hospitals.

VALUE-BASED PAYMENTS, OUTCOMES, AND COSTS

Harold D. Miller, M.Sc.

Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform

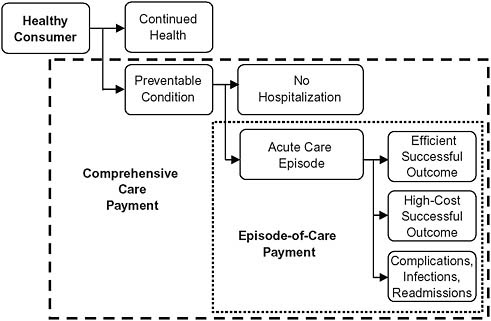

The goals of value-based payment are to give healthcare providers adequate resources to deliver efficient, quality care and to remove the penalties that exist today for improving quality and efficiency. Episode-of-care payment and comprehensive care payment systems can help providers prevent health problems; prevent the occurrence of acute episodes among individuals who have health conditions; prevent poor outcomes during major acute episodes, such as infections, complications, and hospital readmissions; and reduce the costs of successful treatment. By using payment changes to help address these major sources of waste and inefficiency, healthcare costs can be reduced significantly without “rationing” or denying care that patients need (Figure 11-1).

Using Episode-of-Care Payment to Reduce Waste and Inefficiency

Poor outcomes and high costs of major acute episodes can be reduced through the use of episode-of-care payment systems; this system defines a single amount to cover all of the services that are provided to a patient during a single episode of care (e.g., the treatment of a heart attack), rather than making separate payments for each individual service (Robinson,

FIGURE 11-1 How value-based payment systems address sources of waste and inefficiency.

2001). Episode-of-care payment gives the involved providers an incentive to coordinate their activities, eliminate unnecessary services, and avoid complications that require additional services (Miller, 2009).

Defining an Episode-of-Care

There are different versions of episode-of-care payment that address different types of waste and inefficiency (Table 11-1). Although only the fourth and fifth categories—full-episode payments with a limited warranty based on either the type of treatment or diagnosis—can address the full range of problems that occur within a major acute episode, the narrower forms of episode-of-care payment could be used for types of patients where only one issue is of concern, or the narrower forms could be used as transitional steps toward full-episode payment (Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, 2009b).

Encouraging the Use of Higher-Value Providers and Services

As indicated in the fourth and fifth categories in Table 11-1, episode-of-care payment can be based on a particular type of treatment, or it can be based solely on the patient’s diagnosis, particularly where there is clear

TABLE 11-1 Variants of Episode-of-Care Payment That Address Different Aspects of Waste and Inefficiency in Major Acute Episodes

|

Category |

Component of Treatment |

Current Payment System |

Impact of Current System on Waste and Inefficiency |

Improved Payment Approach |

|

1 |

Treatment for conditions present on admission to the hospital |

Hospitals and doctors are paid separately and independently for the care they provide. Most physicians (except surgeons and obstetricians) are paid on a fee-for-service basis. |

No financial incentive exists for doctors and hospitals to work together to improve hospital efficiency. Payers and consumers cannot determine the full cost of treatment in advance. |

Inpatient bundled payment: a single payment covering both hospital and physician services for inpatient treatment |

|

2 |

Treatment for hospital-acquired conditions |

Hospitals are paid for higher diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) or given outlier payments when infections or complications occur. Most physicians are paid additional fees when additional care is provided. |

No financial penalty exists for infections, complications, or readmissions. Payers do not know the full cost of treatment in advance. |

Inpatient warranty: a payment for inpatient services based only on the cost of treatment of conditions present upon admission to the hospital |

|

3 |

Care after discharge from the hospital (e.g., rehabilitation, home health, outpatient care) |

Each provider is paid separately for any services they provide. |

No incentive exists to use posthospital care efficiently. Some desirable services may not be paid for at all. Payers do not know the full cost of treatment in advance. |

Bundled payment for inpatient and postacute services: a single payment covering both inpatient treatment and postacute care |

|

Category |

Component of Treatment |

Current Payment System |

Impact of Current System on Waste and Inefficiency |

Improved Payment Approach |

|

4 |

Readmissions to the hospital for reasons related to the original stay |

Hospitals and physicians are paid for any readmissions in addition to payment for the initial hospital stay. |

No incentive exists to prevent readmissions. Payers do not know the full cost of treatment in advance. |

Full-episode payment with a limited warranty (based on type of treatment): a single payment covering inpatient, postacute care, and preventable readmissions based on the cost of treatment for conditions present on the initial admission |

|

5 |

Choice of the highest-value treatment and facility for addressing the patient’s conditions |

Hospitals and doctors are paid based on the types of treatment provided (e.g., coronary artery bypass surgery) rather than based on the patient’s conditions (e.g., coronary artery blockage). |

No incentive to use lower-cost treatments or facilities that can achieve similar outcomes for the patient’s conditions. |

Full-episode payment with a limited warranty (based on type of diagnosis): a single payment to cover all needed services based on the cost of the highest-value treatment available for a patient’s diagnosis |

evidence as to the appropriate treatment(s) for the diagnosis. Basing payment on diagnosis creates an incentive for a provider to use higher-value treatments—those with equivalent outcomes and lower costs.1

Episode-of-care payment also enables providers to define a single, comprehensive price for an episode of care, which in turn would enable payers (and consumers, if the price is made public) to more easily see the full cost of treatment and to more accurately compare the costs of different providers that could provide the same treatment. Although there is evidence that costs for the same treatment can vary significantly among providers in the same community (Pennsylvania Healthcare Cost Containment Council,

2007), most payers (e.g., Medicare and major health insurance plans) do not give patients strong incentives to use providers who achieve similar outcomes at lower costs.

Why Episode-of-Care Payment Is Better Than Other Payment Reforms

Other payment changes that have been proposed or implemented in an effort to reduce infections, complications, and readmissions are not as effective in changing incentives as a true episode-of-care payment that includes a limited warranty. For example, pay-for-performance systems that give bonuses to hospitals for reducing infections do not change the underlying payment system and its rewards for providing more services. Medicare’s rules that exclude hospital-acquired infections from the diagnosis-related group (DRG) formula do not prevent hospitals from being paid for the complications resulting from those infections or from receiving outlier payments for those cases.

In contrast, if a hospital and physician commit to a “limited warranty,” similar to what has been done by Geisinger Health System through its ProvenCare program (Casale et al., 2007), they have both a financial and quality incentive to improve, and they can also advertise the warranty to patients and payers as a sign of high-quality care.

Experience with Episode-of-Care Payment

Although Medicare has been successfully using a narrow form of episode-of-care payment for over 25 years through the Inpatient Prospective Payment System, there has been relatively limited experience using episode-of-care payments that incorporate warranties or bundle together payments for multiple providers. The projects that have been evaluated have all focused on surgery episodes; the evaluations indicate that payers received savings ranging from 10 to 40 percent, without negative impacts on quality (Cromwell et al., 1997; Edmonds and Hallman, 1995; Johnson and Becker, 1994).

Using Comprehensive Care Payment to Help Prevent Episodes and to Encourage Use of High-Value Services

Despite the many improvements of episode-of-care payment over current fee-for-service payment systems, it still does not encourage preventing episodes of care from occurring in the first place. For example, the primary goal for patients with chronic diseases should not be to reduce the cost of each episode of hospitalization, but to reduce the number of hospitalizations. Many studies have demonstrated that large reductions in

hospitalizations—20 to 40 percent or more—can be achieved through relatively simple, low-cost services such as patient education, self-management support, telemonitoring, and so on (Bourbeau et al., 2003; Cordisco et al., 1999; Gadoury et al., 2005). However, many of these services are not paid for under Medicare or private insurance plans, whereas hospitals and physicians are paid for all hospitalizations, no matter how frequently they occur.

Comprehensive care payment is designed to solve this problem by defining a single amount to cover all of the services needed to manage a patient’s conditions during a fixed period of time, regardless of how many separate episodes of care occur (Miller, 2009). This gives the providers involved in the patient’s care the flexibility to try innovative approaches and tailor services based on the patient’s needs, and it gives them an incentive to avoid hospitalizations and unnecessary or overly expensive services.

In addition to supporting better care management of chronic diseases, comprehensive care payment can encourage the use of higher-value services for treatment of conditions by providing physicians with both the resources and incentive to engage in shared decision making with their patients. Research has shown that the frequency of many types of surgery can be reduced by 20 to 40 percent (O’Connor et al., 2004) and that the inappropriate use of diagnostic imaging can be reduced significantly (Bottles, 2009) when a neutral advisor helps patients make an informed choice, but providers are not compensated or rewarded for doing this under fee-for-service payment.

Table 11-2 provides a side-by-side comparison of episode-of-care payment and comprehensive care payment.

In theory, comprehensive care payment could also be used to encourage greater emphasis on preventing health conditions from occurring in the first place. However, a patient would have to commit to obtain care from the same provider over a multiyear period (and the patient would need a consistent health insurance plan that encouraged such multiyear arrangements) so that if the provider incurred higher costs for prevention today, there would be an assurance that it could reap the benefits of lower treatment expenditures in the future.

Why Comprehensive Care Payment Is Better Than Other Payment Reforms

Although “medical home” initiatives are attempting to change payment systems in order to fill some of the gaps defined above, there is no assurance that these programs will reduce spending since medical homes are not given explicit accountability for improved outcomes (Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement, 2009). At the other end of the spectrum,

TABLE 11-2 Comparing Episode-of-Care Payment to Comprehensive Care Payment

|

Episode-of-Care Payment |

Comprehensive Care Payment |

|

• A single, bundled payment would be paid to a provider or group of providers to cover all of the healthcare services needed by the patient during a specific episode of care (e.g., treatment for a heart attack, or surgery to replace a broken hip). This single amount would be paid instead of individual fees to doctors, DRG payments to hospitals, etc. |

• A periodic (e.g., monthly or quarterly) payment would be paid to a provider to cover all of the healthcare services (including care management, preventive care, and acute care services) needed for management of the patient’s health conditions during that period of time. This single amount would be paid instead of individual fees for services. |

|

• The providers involved in the episode could create joint arrangements for accepting and dividing up the episode-of-care payment among themselves, or the episode-of-care payment could be treated as a budget, and the payer (e.g., a health plan) could divide the payment among the involved providers based on their proportional shares of the care (Gosfield, 2009). |

• A single provider (e.g., a “medical home”) could accept the comprehensive care payment and make payments from it to other providers who deliver care during the time period covered, or the comprehensive care payment could be treated as a budget, and the payer (e.g., a health plan) could divide the payment among the involved providers based on their proportional shares of the total services provided. |

|

• The amount of the episode-of-care payment would vary based on the patient’s diagnosis or treatment and other patient-specific factors. However, there would be no increase in payment to cover preventable adverse events such as errors, infections, or hospital readmissions. |

• The amount of the comprehensive care payment would vary based on the patient’s characteristics—both the specific health conditions they have and other factors affecting the level of healthcare services they will need (e.g., whether they speak English). |

|

• Methods would be established for monitoring and reporting on the quality of health care delivered by providers during each episode, and there could also be bonuses or penalties for the providers based on the quality of care or the outcomes achieved. |

• Methods would be established for monitoring and reporting on the quality of health care delivered by providers during the period of time covered by the payment, and there could also be bonuses or penalties for the providers based on the quality of care or the outcomes achieved. |

|

• Ideally, patients would also receive incentives to use higher-quality or lower-cost providers and adhere to care processes jointly developed by them and their providers. |

• Ideally, patients would also receive incentives to use higher-quality or lower-cost providers and adhere to care processes jointly developed by them and their providers. |

proposals for “shared savings” payments to providers require a focus on outcomes, but do not change the underlying fee-for-service structure and fail to provide any up-front resources to implement new services (Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, 2009a). In contrast, comprehensive care payment gives physicians and other providers both greater

flexibility and greater accountability for the use of resources to deliver high-quality efficient care.

A comprehensive care payment system also avoids penalizing providers for treating sicker patients—one of the major problems with traditional capitation payment systems—because the amount of the comprehensive care payment would vary depending on the number and severity of a patient’s health conditions (Miller, 2009).

Experience with Comprehensive Care Payment

Although capitation systems have been widely used, there is little experience with true comprehensive care payment systems. One example is the Patient Choice program in Minnesota, in which groups of doctors and hospitals are paid based on the risk-adjusted cost of providing care to a population of patients (Robinow, 2008). An evaluation indicated that it contained costs without negatively affecting quality (Lyles et al., 2002). In 2009, PROMETHEUS Payment, Inc. began a yearlong pilot test of “evidence-informed case rates” for chronic disease patients (Prometheus Payment, Inc., 2009), and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts implemented its Alternative Quality Contract (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, 2008), both of which incorporate key elements of comprehensive care payment.

Choosing a Value-Based Payment System

Different types of patients and conditions have different types of waste and inefficiency problems, and different types of payment systems are appropriate for addressing them (Miller, 2009). Episode-of-care payments are most appropriate for conditions where there is not a problem with overuse of treatment (e.g., hip fractures and labor and delivery) but where there are opportunities to reduce the cost and complications of the treatment. As noted earlier, comprehensive care payment should be used for conditions such as chronic diseases where there is concern about unnecessarily high rates of hospitalizations. It should also be used for conditions where there is concern about overuse of certain types of procedures (e.g., heart surgery vs. medical management of heart disease). Areas of underutilization, such as the delivery of prevention services with long-term impacts, may be best addressed through fee-for-service payment.

Setting the Payment Amount

Setting the right payment amount (i.e., the price) is as important as using the right payment method (Miller, 2009). If the amount is too low, providers will be unable to deliver quality care, and if it is too high, there is

no incentive to seek out efficiencies. There are several alternative methods of setting payment amounts, each with advantages and disadvantages (Table 11-3). Different price-setting approaches will likely be needed in different regions and for different providers and services depending on the local market structure; for example, regulation may be needed in regions where providers have a monopoly on particular services, whereas competition can be used in regions where there are multiple providers for most services.

TABLE 11-3 Alternative Ways of Setting Prices in a Payment System

|

Price-Setting Method |

Example |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Regulation: government defines the prices that a provider can charge. |

The Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission sets all-payer rates for hospitals (Health Services Cost Review Commission). |

Avoids cost shifting to small payers. Enables sharing by all payers of costs of uncompensated care and of necessary but expensive services. |

Requires the regulator to determine the “right” price for services. Discourages price competition on services where multiple providers exist. |

|

Price-setting by large payers: large payers define the amounts they will pay providers. |

Congress and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) establish the rates that Medicare will pay. |

Enables consistent pricing of services regardless of a provider’s market power. |

Requires the payer to determine the “right” price for services. Discourages competition on price where multiple providers exist. |

|

Negotiation between payers and providers: payers negotiate with providers to determine prices. |

Commercial health insurance plans negotiate payment rates with major providers in most markets. |

Enables prices to be set based on the cost of delivering services and the value of the services to the payer and its member consumers. |

Result depends on size of payer vs. provider; monopoly/oligopoly providers can demand premium prices, particularly from small payers. |

|

Competition by providers: providers set prices in order to attract consumers. |

The State of Minnesota has created a process to define “baskets of care” for asthma, back pain, obstetrics, and others; providers who want to offer those packages of services set their price, and all (commercial) payers will be required to pay the same price (Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; Minnesota Department of Health). |

Enables providers to define the “right” price for services, and gives them the opportunity to attract additional volume based on greater efficiency. |

Requires existence of multiple providers with similar quality to enable competition on price and with sufficient capacity to handle shifts in patient volume. Requires a benefit design that gives consumers an incentive to use lower-cost providers. |

Achieving Alignment of Multiple Payers

Finally, for changes in payment systems to enable a healthcare provider to transform the way it delivers care for all of its patients, most, if not all, of the payers in the community need to change their payment systems in similar ways. To avoid antitrust concerns, states or nonprofit regional health improvement collaboratives can facilitate consensus among local payers on payment changes (Miller, 2009). However, Medicare needs the ability to participate in such regionally defined payment reforms in order to achieve true alignment of incentives.

BUNDLED AND FEE-FOR-EPISODE PAYMENTS: AN EXAMPLE

Francois de Brantes, M.S., M.B.A., Amita Rastogi, M.D., M.H.A.,

Alice Gosfield, Doug Emery, M.S., and Edison Machado, M.D., M.B.A.

Bridges to Excellence

Ideas about how to pay providers to improve quality and reduce costs are the foundation for many current discussions about national healthcare reform. Most experts agree that a fundamental problem of the nation’s health system is that both the current fee-for-service and the capitation-style models of reimbursing providers encourage volume-based practice patterns rather than value-driven care (Lee and Ferris, 2009). Providers are rewarded for “doing things” (often too many or not enough), rather than delivering quality services that are proven to keep people healthy, reduce errors, and help avoid unnecessary care.

As opposed to fee-for-service, bundled payments place the focus of care on the entire continuum for a given condition (Paulus et al., 2008). Contrary to capitation that is based on per population payment irrespective of whether a member has a condition or not, payment by episodes are triggered only when a member has a condition and insulates providers from risk of occurrence. Creating a single reimbursement fee for a condition holds the providers accountable for delivering quality care in the most cost-effective manner, while adjusting payments based on patient-severity factors makes the system fair. Fee-for-episode payments with the right incentives would focus providers in managing care proactively in a patient-centered, coordinated fashion, reducing complications and improving outcomes across the continuum of care (Mechanic and Altman, 2009).

PROMETHEUS Payment is one such approach that seeks to ignite a transformation in healthcare payment by challenging the way providers and insurers conduct business—moving away from unit-of-service payment to episode-of-care payment (de Brantes and Rastogi, 2008). This consumer-centered model has developed “evidence-informed” case rates for several chronic, acute medical and procedural conditions, defining what services

are included in episode payments and adjusting reimbursements based on patient severity. It is built on a quality-improvement framework where a physician scorecard is tied to the potential for reducing complications. The model was launched in 2006 (Prometheus Payment Inc., 2008), and now has four pilots across the country through the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and is also being tested informally in several communities. This report outlines the lessons learned from PROMETHEUS.

Episodes of Care

At its core, the PROMETHEUS Payment model centers on packaging payment around a comprehensive episode of medical care that covers all patient services related to a single illness or condition. Covered services are determined by commonly accepted clinical guidelines or expert opinion that lay out the tested, medically accepted method for treating the condition from beginning to end.

To date, PROMETHEUS Payment has developed evidence-informed case rates for a significant number of acute events, procedures, and chronic care, including heart attacks, hip and knee replacement, diabetes, asthma, congestive heart failure, and hypertension, to name a few (Rastogi et al., 2009). These existing evidence-informed case rates can potentially affect payment for almost 33 percent of the entire insured adult population and represent a significant amount of dollars spent by employers and plans.

Evidence-informed case rates are budgeted at the patient level and encompass costs of all necessary care for a given condition (physician visits, prescriptions, lab tests, imaging, etc.) across the care continuum for a predefined period of time. The covered services are bundled across all providers who would treat a given patient and the case rate is adjusted to take into account the severity and complexity of the individual patient’s condition. However, services normally included within the total costs of patient care but used to care for potentially avoidable complications (PACs) are largely a result of care defects and are attributable to provider actions. Within PROMETHEUS, costs of these services are separated from costs attributable to patient factors and used to develop a warranty pool against care defects. The evidence-informed case rates therefore cover costs for typical and reliable care that is adjusted based on patient demographics and comorbidities, and an allowance that serves as a warranty or buffer against PACs.

Potentially Avoidable Complications (PACs)

PACs are usually deficiencies in care that cause harm to the patient, yet might have been prevented through more proactive care—for example, when a patient with diabetes ends up in the emergency room because of uncontrolled blood sugar levels. PACs represent a substantial opportunity

for improving patient care and reducing total cost of care. Unfortunately, PACs remain all too common in the U.S. healthcare system.

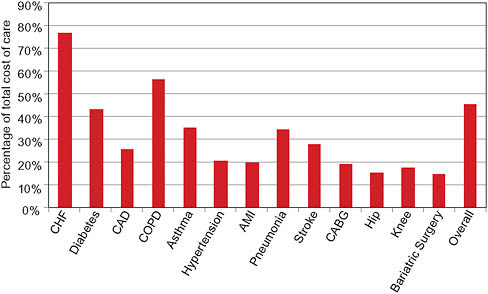

In analyzing large sets of national claims data, the PROMETHEUS Payment team found that an average of 21 to 77 cents of every dollar spent on chronic conditions and 15 to 34 cents of every dollar spent on acute medical care or procedural conditions are attributable to PACs (Figure 11-2). PACs are abundant and expensive, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars for less than optimal care, and are a significant source of variation in costs due to errors, oversights, and failure of care coordination. Preventable hospitalizations constitute the bulk (67 percent) of all chronic medical PAC costs. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–defined “never events,” hospital-acquired conditions (9.5 percent), and readmissions (44 percent) constitute the bulk of inpatient acute medical and procedural PAC costs, others being PAC costs during the index stay and professional and pharmacy costs associated with these PACs.

PACs represented about 15 percent of the total of $45 billion of annual costs of care in a large national claims dataset after modeling 13 evidence-

FIGURE 11-2 Cost of care defects as percentage of total costs of care for specified conditions/procedures.

NOTES: AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Hip = hip replacement surgery; Knee = knee replacement surgery; Overall = weighted average of costs all care defect as a proportion of all costs of care for the 13 evidence-informed case rates in this figure.

informed case rates.2 Using best practices quoted in literature, these care defects could be decreased by half (de Brantes, under review) leading to a net savings opportunity of $3 billion (Table 11-4). Reducing these defects to zero would net close to $6.5 billion.

Given that there are 3.5 million covered lives under the age of 65 in this dataset, total potential savings for the 200 million commercially insured in the country could be approximately $165 billion. If these defects were reduced to zero, the U.S. healthcare system could save $355 billion.

Under PROMETHEUS Payment, the incentive for providers to act on and reduce PACs comes directly from the savings found in reducing them. A PAC allowance is calculated and included in each evidence-informed case rate price irrespective of the occurrence of PACs. This amounts to 50 percent of dollars spent today on these conditions. Should complications occur, this portion of the budget serves to offset the actual costs of the corrective treatment (de Brantes et al., 2009). The PROMETHEUS model rewards providers with fewer PAC rates and better-quality scores, giving them an additional allowance as “margin” for provider practice reengineering to improve care delivery. If providers can reduce or eliminate PACs, they can keep the entire allowance as a bonus and significantly improve their profit margin per patient, as the example depicted illustrates (Box 11-1).

One of the important features that makes PROMETHEUS Payment different from other healthcare payment systems and typical pay-for-performance models is its strong incentive for clinical collaboration to ensure positive patient outcomes. In addition to earning the base evidence-informed case rate payments, providers are given the opportunity to earn bonuses through a comprehensive quality “scorecard” tied to the reduction of potentially avoidable complications.

Comprehensive Quality Scorecard

The PROMETHEUS Payment comprehensive quality scorecard contains a variety of metrics built and expanded on the Bridges to Excellence Care Links that track and evaluate care across the entire scope of treatment (Rosenthal et al., 2008). These include scores for a range of items, including (1) each provider’s performance in meeting the clinical practice guidelines that define the evidence-informed case rates, (2) positive intermediate outcomes that lead to patient risk reduction and the avoidance of preventable complications, and (3) the patient’s satisfaction with care received.

When evidence-informed case rates are paid, a portion of the budget is withheld and then paid out depending on the scores that the providers and their clinical collaborators earn. To create a very clear incentive for clinical

TABLE 11-4 Savings Estimate: Commercially Insured Population

|

|

Total for Six Chronic Conditionsa (n = 1,361,685) |

Total for Seven Acute Medical / Proceduresb (n = 22,242) |

Total for 13 Conditions/Acute Medical / Proceduresc (n = 1,383,927) |

Total for 13 Conditions /Acute Medical / Proceduresc (n = 1,383,927) |

|

Base cost of care |

$6,909,752,883 |

$736,537,303 |

$7,646,290,186 |

$7,646,290,186 |

|

Underuse allowance |

$687,559,658 |

$0 |

$687,559,658 |

$687,559,658 |

|

Evidence-informed cost |

$7,597,312,541 |

$736,537,303 |

$8,333,849,844 |

$8,333,849,844 |

|

PAC target rate |

24% |

10% |

23% |

0% |

|

Allowance for PACs |

$3,319,149,766 |

$95,329,613 |

$3,414,479,379 |

$0 |

|

Total expected cost |

$10,916,462,307 |

$831,866,917 |

$11,748,329,224 |

$8,333,849,844 |

|

Net savings opportunity |

$2,951,882,322 |

$95,329,613 |

$3,047,211,935 |

$6,461,691,315 |

|

Net savings for all commercially insured plan members |

$162,353,527,710 |

$5,243,128,730 |

$167,596,656,440 |

$355,393,022,299 |

|

aThese conditions include congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and hypertension. bThese conditions include acute myocardial infarction (AMI), pneumonia, stroke, coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), hip replacement surgery, knee replacement surgery, and bariatric surgery. cThese conditions include the 13 conditions listed above. |

||||

|

BOX 11-1 Example of Payments Under PROMETHEUS Payment A 45-year-old non-insulin-dependent diabetic with obesity and hyperlipidemia is routinely managed by an internist for control of his diabetes. He is also periodically seen by a cardiologist who is in a separate practice from the internist. The patient is adherent with his antidiabetic drugs, the antiplatelet therapy, and his daily statin intake. Given the patient’s comorbidities, the severity-adjusted prospective budget for this patient for professional and pharmacy services would include $6,500 for 1 year of management of diabetes, an additional $1,000 for care coordination and provider practice reengineering efforts, and a $3,000 allowance for potentially avoidable costs, for a total budget of $10,500. The patient is managed proactively and does not have any emergency room visits or hospitalizations during the year. He does have an ultrasound of the heart and a retinal exam during the year, which are included in the typical portion of the budget. Overall the actual claims costs for professional and pharmacy services for this patient for 1 year total $6,700. The two physicians are therefore eligible for a “joint” bonus of $3,800. |

collaboration, the final scores depend 70 percent on what the individual provider does and 30 percent on what every other provider treating that patient for that condition has done. The value of coordination across settings is critical, particularly in the management of chronic conditions.

Conclusion

Fee-for-episode payments when constructed fairly and with the right framework offer a realistic, rational, and sustainable blueprint for a new healthcare payment system. They could effectively promote and reward high-quality, efficient, patient-centered care; provide common performance incentives for all parties; and create an environment where doing the right things for patients would also allow providers and insurers to do well financially.

In the short term, successful implementation of a bundled payment system would not require any form of organizational change to the delivery system; it would simply require an act of collaboration in the current system. The savings achieved could be divided up among the collaborating providers based on a predefined formula according to the proportion of care they are accountable for. The payer could retain a role of an integrator across providers and as budgets are set prospectively, payment could continue for all fee-for-service claims submitted.

Quarterly, the actual spending could be reconciled against the budgets and bonuses paid for the upside, and any downside risk could be managed

by withholds. In the long term, as bundled payments would become the norm, provider groups would organize to create efficient provider communities that share in the upside and a more structured payment methodology would emerge.

Interestingly, early reports from the PROMETHEUS pilot implementation sites have demonstrated a curious ethical dilemma among hospital administrators against adopting PROMETHEUS. As demonstrated in the report, the savings are achieved primarily by reducing the waste within the healthcare system of which unnecessary hospitalizations are a major portion of the costs. This has caused a financial tension in the current hospital-centric provider organizations. Results from other pilot sites would demonstrate the extent to which bundled payments actually achieve their objective of decreasing costs and improving quality.

EFFECTIVE HEALTH INSURANCE EXCHANGES: AN EXAMPLE

David R. Riemer, J.D.

Community Advocates Public Policy Institute

Health insurance exchanges can be a powerful mechanism for lowering healthcare costs and improving healthcare quality. Evidence from one of the nation’s most long-lasting and successful exchanges, operated by the Wisconsin State Employee Health Plan in Dane County, suggests, however, that those savings and quality improvements can be realized only under the following specific conditions:

-

The exchange overcomes adverse selection and presents health insurance companies with a pool of potential enrollees whose average or near-average risk profile does not discourage insurers from submitting bids.

-

The exchange has a pool of enrollees that is large enough (20 percent or more of those not enrolled in Medicaid or Medicare) to make it economically necessary for insurers to submit bids.

-

The enrollees in the pool have a clear economic incentive to select the health insurance plans that submit the lowest risk-adjusted bids, by requiring enrollees to pay most of the extra cost of plans whose risk-adjusted bids are higher.

If properly designed and implemented in all states, exchanges could function as the “public plan” that many in Congress and the President are looking for to discipline the U.S. health insurance market, lowering cost growth so as to “bend the cost curve” in health care and improving quality. Exchanges’ cost-reducing and quality-improving potential both stem from

the same incentive they trigger: the incentive of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other insurance companies to gain customers, increase revenue, and enlarge profits by reducing the widespread error, waste, and inefficiency that permeate the delivery of health care in the United States.

What Is a Health Insurance Exchange?

An exchange is a formal structure, typically created (and at times managed) by government, which pools buyers of health insurance and gives them unimpeded access to multiple competing health insurance plans. Exchanges provide participating individuals with objective information about:

-

Standard benefit packages3 provided by plans;

-

The features of the competing healthcare plans themselves;

-

The plans’ doctors, clinics, and hospitals;

-

The plans’ premiums;

-

The portion of their premiums enrollees must pay to join a particular plan; and

-

The enrollment process.

Through exchanges, individuals enroll in their choice of healthcare plan. There is no underwriting; renewal is guaranteed. The plans must agree to this requirement as a condition of obtaining access to the exchange’s large pool of enrollees.

The exchanges—not the plans—also decide the “format” for setting premiums, such as whether premiums will be bid on a per-person or a family basis, or whether premiums may be adjusted based on age or other risk factors. Within these constraints, however, the plans set and bid their own premiums.

Finally, exchanges oversee and facilitate the enrollment process, coordinate the premium payments to chosen healthcare plans, and perform a variety of other essential administrative functions.4

Wisconsin’s Health Insurance Exchange

Since 1983, the Wisconsin State Employee Health Plan, administered by the Department of Employee Trust Funds, has operated a health insurance exchange for approximately 80,000 state employees. The benefit package, negotiated with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees and other powerful unions, is uniform across the state and excellent in scope. The benefits are also the same whether an employee enrolls in an HMO, which submit bids in the counties of the HMO’s choice, or the statewide fee-for-service Standard Plan. Employees choose during an annual open enrollment period among the “qualified” risk-bearing HMOs—there are at least two HMO choices in almost all counties, and four or more HMOs in many counties—or select the Department of Employee Trust Funds’ self-insured Standard Plan (Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds, 2004b). Employees have an incentive to choose a low-cost HMO plan because they pay much (if not most) of the extra cost of any higher-cost HMO plan or the higher-cost Standard Plan.5 The current formula, in place since 2004, places all HMOs in one of three tiers based on their risk-adjusted premium bids. Tier 1 includes the HMOs that submit the lowest premiums or “close to” the lowest premiums. Tier 2 includes the significantly more expensive HMOs. Tier 3 is occupied by the high-cost fee-for-service Standard Plan. Employees have a clear economic incentive to choose a Tier 1 HMO because their share of the premiums is limited (in 2009) to $31 per month for single coverage and $78 per month for family coverage. A Tier 2 HMO costs more than twice as much per month—$69 for singles, $173 for families. The Tier 3 Standard Plan costs over twice as much again—$164 for singles and $412 for families.

The Dane County Exchange Model

The Department of Employee Trust Funds does not really operate a single statewide exchange; rather, it oversees 72 separate county exchanges. Depending on where a state employee resides, the employee enrolls in a different countywide exchange. The benefits are the same in all counties. The risk profile is comparable across counties. The incentives are identical in each county. The HMO selections, however, vary from county to county

|

they perform, exchanges typically charge a small fee, which is built into the premiums paid by enrollees but, of course, retained by the exchanges themselves. |

(Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds, 2004b). But the biggest contrast lies in the way the exchange operates in Dane County compared to how it works in the other 71 counties.

Dane County, the seat of state government and home to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was the residence in 2006 for approximately 40 percent of all state employees, or 81,832 of the Department of Employee Trust Funds’ covered lives. This large pool exceeded 20 percent of Dane County’s entire population not enrolled in Medicaid,6 Medicare, or other federally financed health insurance programs.

The exchange model in Wisconsin’s other 71 counties has the same features: equal benefits, comparable risk profile, and identical incentives. But one essential element is missing: a large pool exceeding 20 percent of the non-Medicaid, non-Medicare population. In no other locale does the Department of Employee Trust Funds come close to having this big a pool in its countywide exchange.

Bending the Cost Curve

The results? In the Dane County exchange model, where enrollees get an annual choice among four excellent HMOs, premium rates are much lower than in the other 71 counties. The Dane County exchange model has monthly HMO premiums in 2009 that average $528 for singles and $1,316 for families. In the other counties, the monthly average premium is $628 for singles and $1,565 for families—an annual average of $1,198 more for singles and $2,995 more for families.7

Of equal importance, the inflation rate for the Dane County exchange model has been substantially less than the inflation rate for the exchanges in the state’s other 71 counties. Between 2004 and 2009, the Dane County exchange model’s HMO premiums increased 35 percent for singles and 37 percent for families. In the other 71 counties, meanwhile, HMO premiums grew by 42 percent for singles and 45 percent for families—an increase of at least 18 percent.8

It is important to note that the Dane County exchange model did not involve any significant alteration of deductibles or copays to achieve these results. By contrast, U.S. employers in general have steadily increased de-

ductibles and copays in an artificial effort to contain premium growth. Yet despite this cost shift to workers, Kaiser Family Foundation data indicate that, compared to the most recent 6-year period (2004 through 2009) for the Dane County exchange model, U.S. employers’ average premiums rose faster—39 percent for singles and 40 percent for families—during the most recent 6-year period for which we have national data (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2008).

The Lesson for Policy

As Congress and the President forge a compromise on health insurance reform that may require removing the so-called public option (i.e., a government-run, Medicare-like insurance program), Congress and the President should give serious consideration to the Dane County exchange model as an economically sound—and politically acceptable—mechanism for “bending the cost curve.”

The model offers what liberal Democrats most want: excellent benefits, a wide choice of health insurers and providers, and lower cost growth. For conservative Democrats and Republicans, it offers a proven way to contain costs without a government-run insurance company; it instead deploys market forces—competition, choice, and incentives—to discipline insurers’ premiums.

The Dane County exchange model also promotes quality. To bid competitive premiums, insurers must work closely with doctors, clinics, and hospitals to drive out the errors, waste, and inefficiency that permeate the healthcare system.

VALUE-BASED INSURANCE DESIGNS AND HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Niteesh K. Choudhry, M.D., Ph.D.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School

Incentive formularies and other similar benefit designs are used by the majority of public and private insurers to reduce healthcare spending (Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 2009), yet available data suggest that they achieve their goals inefficiently (Goldman et al., 2007). Copayments are set in a one-size-fits-all style that may create imperfect incentives for patients. Copayments for essential, high-value services are often set too high, and their resultant underuse leads to missed opportunities to prevent and treat morbid and expensive diseases; copayments for nonessential, low-value services are sometimes not set high enough to minimize their unnecessary use.

Value-based insurance design (VBID) is a cost-sharing system that cre-

ates appropriate incentives for patients based on the evidence-based value of specific services. Copayments are set at low levels for high-value services and at high levels for those services that are less valuable. This is radically different from the conventional system of basing copayments on the expense of treatment or medicine. This strategy was first proposed to address the dual goals of quality improvement and cost reduction for prescription drugs (Chernew et al., 2007; Fendrick et al., 2001). VBID may also be applied to nondrug treatments, healthcare providers, and disease management programs, although these have received less attention. As of 2008, VBID plans involving incentive copayment reductions had been implemented by more than 15 percent of large self-insured employers, with virtually all others expressing interest in initiating a VBID plan within the next 5 years (Mercer National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, 2008).

Limited but Promising Evidence Supporting VBID

The existing evidence evaluating VBID is limited but supports its ability to improve targeted service use and to potentially improve clinical outcomes and reduce overall healthcare costs. Some promising examples that suggest the broader impact of this new approach include the following:

-

In a prospective study, a large employer eliminated copayments for generics, reduced copayments by 50 percent for brand-name drugs, and demonstrated a 3 to 4 percent increase in adherence, as compared to a control firm (Chernew et al., 2008).

-

Cost-sharing reductions introduced by Pitney Bowes were associated with a 26 percent reduction in emergency department visits for patients with diabetes and a slower rate of growth of overall healthcare costs than benchmark companies (Mahoney, 2005).

-

An HMO eliminated blood glucose monitor copayments for patients with diabetes and observed a doubling of the rate of self-monitoring initiation for patients treated with oral agents and a 0.6 percent reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels for initiators who had poor diabetes control at baseline (Soumerai et al., 2004).

Further supplementing the limited research base are several published, modeling studies (Table 11-5).

Two of these economic models evaluated the impact of eliminating cost-sharing for a standard secondary prevention regimen (beta-blockers, statins, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEI]/angiotensin receptor blockers [ARB], and aspirin) for acute myocardial infarction patients in typical insurance plans and those covered by Medicare Part D (Choudhry et al., 2007, 2008). Both analyses found that while providing full coverage increases drug expenditures, enhanced adherence will reduce mortality and

TABLE 11-5 Published Evaluations of Impact of Cost-Sharing Reductions on Total Health Care Costs

|

Disease |

Drugs |

Source |

Analytic Method |

Payor |

Time Frame |

Impact on per Patient Total Costs |

|

|

Absolute |

Relativea |

||||||

|

Myocardial infarction |

Beta-blockers, statins, ACEI, aspirin |

Choudhry et al., 2008 |

Cost-effectiveness analysis |

Medicare |

Lifetime |

−$2,453 |

−2% |

|

Beta-blockers, statins, ACEI/ARB, aspirin |

Choudhry et al., 2007 |

Cost-effectiveness analysis |

Commercial |

3 years |

−$1,181 |

−6% |

|

|

High cholesterol at moderate or high risk of coronary artery disease |

Statins |

Goldmanet al., 2006 |

Claims-based cross- sectional model |

Commercial |

1 year |

−$5,628b |

−1% |

|

Diabetes |

ACEI |

Rosenet al., 2005 |

Cost-effectiveness model |

Medicare |

Lifetime |

−$922 |

−1% |

|

NOTE: ACEI = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker. a Published VBID analyses provide estimates of absolute cost savings from copayment reductions. Because these models assess cost savings over a wide range of time frames, the estimates are not directly comparable. To overcome these differences, relative savings can be calculated from the published data. |

|||||||

rates of nonfatal reinfarction, stroke, and congestive heart failure readmission and consequently result in a net cost savings. Other analyses involving eliminating copayments for statins in patients at moderate or high risk of coronary artery disease (Goldman et al., 2006) and ACEI for patients with diabetes (Rosen et al., 2005) have also found substantial total cost savings. Although these analyses used different analytic techniques to evaluate different patient populations, drugs, payer perspectives, and time frames, their results are relatively consistent.

Despite the limitations of the published data evaluating VBID (Fairman and Curtiss, 2008), employers who have implemented these benefit design plans report success from them (Mercer National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, 2008), and accordingly there has been substantial hope that the more widespread use of VBID plans will lead to reductions in overall healthcare spending.

Generating National Estimates

Generating national estimates of the impact of VBID scaled to national levels is significantly hampered by the nascent research base in the area—whether based on experimental design or on modeling. However, as a quicker approach, we can use estimates of the relative net savings from existing economic models of copayment reductions, apply these estimates to overall health expenditures for VBID candidate conditions, and test the generated results across a range of plausible relative savings estimates.

Applying the range of expected relative savings generated from existing economic evaluations to current national expenditure for the candidate conditions yields national estimates of health savings from VBID (Table 11-6). Even with a relatively conservative assumption of 1 percent cost reduction from VBID applied to just five conditions, annual savings are estimated to be more than $2 billion.

Limitations of This Approach

There are several potential limitations to this simplistic approach. First, because the true impact of VBID on healthcare expenditure is unknown, this analysis relies on estimates derived from economic models, which in turn are reliant on potentially imperfect estimates of elasticity of demand. Second, the use of relative rates as a basis for calculating national savings estimates may be inappropriate if the cost savings from copayment reductions do not accrue at a constant rate (i.e., if there is violation of a proportional hazards assumption). As observed, relative cost savings range from 1 to 6 percent and are not obviously related to the study time horizon, thereby minimizing this concern. Further, the magnitude of these results is

TABLE 11-6 Projected Annual National Savings from Selective Copayment Reduction for Five Common Chronic Conditions

|

Disease |

Annual National Expenditure (excluding Medicaid) in Billionsa |

Annual Savings from VBID Across a Range of Relative Savings Estimates, in Billions |

||

|

1% |

2.5% |

6% |

||

|

Heart disease |

$71.99 |

$0.72 |

$1.80 |

$4.32 |

|

COPD/Asthma |

$44.22 |

$0.44 |

$1.11 |

$2.65 |

|

Hypertension |

$43.65 |

$0.44 |

$1.09 |

$2.62 |

|

Diabetes |

$41.83 |

$0.42 |

$1.05 |

$2.51 |

|

Hyperlipidemia |

$25.34 |

$0.25 |

$0.63 |

$1.52 |

|

Total |

$227.04 |

$2.27 |

$5.68 |

$13.62 |

|

aRecent nonoverlapping national estimates of total healthcare expenditures associated with different chronic conditions can be obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s 2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (AHRQ, 2005b).VBID plans are unlikely to be implemented by public plans that have very little cost sharing, such as Medicaid; thus Medicaid’s contribution to overall health spending for these conditions should be excluded from national expenditure estimates. Disease-specific estimates, less Medicaid expenditures, for those conditions for which relative cost savings were generated above are presented here. |

||||

consistent with those that would be expected from a large, although primary cross-sectional, literature examining the impact of increasing medication adherence on total healthcare spending (Balkrishnan et al., 2003; Sokol et al., 2005), which is the central mechanism by which VBID is believed to work. Third, VBID is unlikely to be used by payers who already set copayments at a very low level. Spending attributable to Medicaid, but not other payers, was removed from the calculations and thus the amount of spending that VBID could potentially affect may have been overestimated. Finally, the national expenditure estimates used for this analysis, by necessity, aggregate groups of conditions into single disease categories, such as “heart disease” and do not account for patients with more than one related condition (for example, copayments for ACEI may be offered to patients with diabetes and coronary disease). Further, these estimates do not distinguish between patients of different disease severities and, thus, the analysis ignores the fact that VBID may have little impact on health spending for some patients within these disease groupings and a large impact for others.

Strategies for Maximizing the Cost Savings from VBID

As more sophisticated modeling exercises are undertaken and the results of ongoing implementations become available, there are several strategies for maximizing the cost savings from VBID that should be carefully explored (Choudhry et al., 2007).

Because patients with a given disease are heterogeneous, the reduction in clinical events that results from more appropriate medication use should be greatest for patients at the highest risk for preventable events (Chernew et al., 2007). As a result, the potential cost savings from selective copayment reduction may be maximized by preferentially reducing copayments for high-risk patients with high-risk conditions, rather than reducing cost sharing for all patients with a given condition or for all patients receiving a particular treatment. In this way, VBID is sensitive to the characteristics of diseases, treatment, and patients. Targeting VBID is more resource intensive than broad-based copayment reductions, and these implications must be fully considered (Choudhry et al., unpublished).

Selectively raising copayments for low-value services may achieve cost-savings by directly reducing the use of unnecessary services. A wealth of data demonstrates the effect of this strategy, which may be particularly important to offset the initial increase in costs from copayment reductions, yet this important part of VBID has not been successfully implemented in practice. Goldman and colleagues modeled the effect of raising statin copayments for low-risk coronary artery disease prevention while lowering them for higher-risk patients and found no change in short-run health plan costs and reduced long-run costs that were similar in magnitude from those obtained by only reducing copayments for higher-risk patients (Goldman et al., 2006). The critical challenge remains to accurately identify the value of individual health services.

Although VBID has been used primarily for prescription drugs, its scope extends to other high-value medical interventions that are influenced by cost sharing. For example, relatively small differences in copayments are associated with substantial changes in mammography rates for women who are recommended to undergo screening (Trivedi et al., 2008). VBID can also be used to promote the choice of different treatment modalities for single diseases or the selection of healthcare providers. For example, the use of medical therapy rather than percutaneous intervention for patients with stable angina or watchful waiting rather than surgery for patients with localized prostatic cancer may be stimulated by copayment changes. Of course, these complex trade-offs often require a nuanced evaluation of clinical circumstance and patient preference. There may, nevertheless, be situations in which the clinical evidence is sufficiently clear to allow benefit design to assist in appropriate treatment choice.

Policy Implications

VBID is a novel benefit design strategy that has attracted much attention in the payer community. While the evidence supporting its ability to improve healthcare quality and reduce health spending has notable limita-

tions, reasonable analyses based on conservative assumptions support the promise of VBID to be a useful adjunct for maximizing healthcare value.

TIERED-PROVIDER NETWORKS AND VALUE

Lisa Carrara

Aetna

There is broad agreement among clinicians, payers, and employers that our current healthcare system needs improving. Along with cost-related concerns, there are healthcare inefficiencies and quality gaps in care delivery. As consumers take more responsibility for healthcare decision making, the demand for specific information on healthcare quality and costs is gaining momentum.

This paper focuses on Aetna’s model of a tiered specialist network that is based on provider performance evaluations. Using certain industry-recognized clinical performance measures and cost efficiency criteria, Aetna analyzes performance of contracted physicians in 12 specialty categories.9 Those who meet necessary standards receive the Aexcel designation. The success of this approach is predicated on the assumption that Aexcel designation can identify and then encourage patient access to specialists who have shown that they deliver efficient, effective care, which can lead to speedier recoveries, fewer complications, and fewer repeat procedures.

Managing Healthcare Costs

One option for managing healthcare costs has been the growth of consumer-directed health plans that place more decision making and financial responsibility directly on consumers. However, for consumer-directed health plans to be effective, consumers need clear, easy-to-understand information. A response to this call for more transparency of cost and clinical quality has been the growth of tiered networks and consumer decision support tools.

Aetna was the first national health insurer to add a consumer-directed health plan to our comprehensive product mix. This effort was closely followed by an introduction of a specialist designation program, called Aexcel, within a tiered network benefit design. The Aexcel designation is given to specialists who demonstrate effectiveness in the delivery of care based on a balance of certain measures of clinical performance and cost-efficiency. Like

tiered pharmaceutical benefits, which set different copayments for generic, brand-name, and nonformulary drugs, tiered networks encourage patients to see Aexcel-designated physicians when in need of specialty care.

Aetna members in all or parts of 23 states and the District of Columbia have online access to clinical quality and efficiency information for Aetna-participating physicians in 12 specialty categories. These specialty categories account for 70 percent of specialty spending and 50 percent of overall medical costs. Specialists who have met certain clinical performance and cost-efficiency standards are designated as physicians that have met these Aexcel standards.

The clinical performance criteria are based on nationally recognized standards, consistent with leading associations, such as the National Quality Forum, National Committee for Quality Assurance, American Board of Medical Specialties, American Osteopathic Association, American Heart Association, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. We also look at external recognition and board certification information specific to the physicians’ Aexcel specialty. When evaluating efficiency, we analyze the cost for services and the number and type of services performed. Our review includes inpatient, outpatient, diagnostic, laboratory, and pharmacy claims. We also use risk-adjustment factors to account for differences in the use of healthcare resources.

Early Observations

Provider performance evaluation programs and the growth of tiered networks are starting to shift behaviors among patients, physicians, and other constituencies in health care. For example, we see a continuous increase in use of our Web-based decision support member tools. As a result, we hope that consumer engagement may ultimately lead to increased provider competition leading to greater value for the consumer. As consumers are better able to assess cost and clinical quality (through Web-based tools), they will make decisions that could result in providers improving their cost competitiveness and enhancing the clinical quality of their services.

Already one of the real benefits of Aexcel has been the way we are able to use the data to better engage physicians. We found many physicians do not have access to information about how their practice compares to their peers in the community. Through the Aexcel evaluation and designation process, we are able to work with physician groups to assist them in better understanding their practice patterns and where they might make improvements.

Savings Estimates

Aexcel providers have demonstrated performance that is 1 to 8 percent more cost-efficient than their peers within a given network. This efficiency calculation is derived based on a plan design that considers specialists in the 12 specialist categories who do not receive Aexcel designation as out-of-network providers for Aexcel members. This plan design also assumes no out-of-network benefits. By implementing such a plan design model and assuming roughly 90 percent use of Aexcel-designated specialists (some specialists that may not have met the Aexcel criteria may sometimes be needed for access purposes, consequently 100 percent use probably will not occur), we estimate a customer may save in a range of 3 to 4 percent of its annual claims in its first year, offset by a service charge.

If this type of tiering program were implemented more broadly, we could extrapolate our program savings calculation more broadly. A review of the experience of Aetna members in 2008 and 2009 showed that, on average, Medicare members used twice as many specialist services as their commercial counterparts and that Medicaid members used about the same, or slightly more. Aetna’s Medicaid members are primarily under age 65 and not dually eligible.

Based on our experience, we hypothesize that the savings realized on a national scale might be similar or potentially greater than the savings that our commercial customers realize as savings are directly tied to use of specialist providers, which Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries generally use at greater frequencies than commercially insured members at Aetna. Our estimates apply only to those specialties included in our tiered network design.

Drivers of Success

Aetna’s experience has revealed some critical drivers of success that are essential in implementation of tiered networks. We establish a tiered network in markets where

-

Significant customer commitment and willingness to collaborate exists,

-

The existing Aetna network is sufficiently robust to allow for the selection of a performance specialist network, and

-

Variation in cost-efficiency across specialists is significant such that selecting a performance network results in projected financial savings sufficient to warrant a limitation of the network.

Benefit plan design with member incentives that requires the exclusive use of Aexcel-designated physicians for the 12 specialty categories appears

to be more effective in persuading members to use specialists in the tiered networks. Physicians’ participation in the designation process greatly contributes to the successful roll out and maintenance of tiered networks. We proactively collaborate with the medical community, including outreach to key medical organizations and local markets’ staff engagement with providers in their geographical areas. Our Aexcel selection methodology aligns with the physician contracting process and allows for performance evaluation at the group level rather than individual physician level.

Future Considerations

Even though Aexcel provides a promising model for broader replication, there are still gaps in data that need to be considered as we move forward. The claim-based clinical quality and efficiency information is based on Aetna member claim data only. We support industry-wide data collection initiatives, and when this credible combined data becomes available, we will consider using it in our evaluations. The information used to evaluate physicians does not include all procedures, lab, or pharmacy data—only those for which Aetna has claim data. We strongly encourage physicians to reach out to us with additional data they might have in medical charts that is not available to us through claims data. Some providers and provider groups cannot be evaluated for Aexcel designation due to too few Aetna patient encounters for credible analysis. During the review process, we consider that some doctors may treat patients with more than one health issue or more complex conditions. While we use industry-recognized methods for accounting for this issue, a perfect mechanism that accounts for all variations between patient populations still does not exist.

Peer performance fluctuation—since providers are evaluated against their peers in the same specialty and in their geographical area, changes in peer performance affect performance results of a given provider, which may affect projected savings. Another consideration is that provider contracting and movement (e.g., leaving an existing group, joining a new practice, gaining or losing an affiliation with a hospital) causes fluctuation in network configuration and savings from year to year. This is a characteristic common to all provider networks.

Physician performance measurement initiatives and healthcare transparency are at the top of the list for professional medical organizations, health plans, legislators, consumer rights groups, and providers themselves. Many health plans now operate under the oversight of an external monitor, a third party that regularly audits these selection processes. Recommendations by the external monitor to the health plan are a natural and expected outcome of these audits and are intended to ensure complete compliance with the agreement provisions and review requirements. Health plans are expected to incorporate the recommendations and make adjustments to

their programs as appropriate in a timely manner. Failure to do so may result in disciplinary and financial consequences to the health plan.

Conclusion

The Aetna Performance Network featuring Aexcel-designated specialists is one of a series of industry-leading initiatives from Aetna designed to address rising medical costs, maintain access to quality care, and help consumers make more informed healthcare decisions. Aexcel designation can encourage access to specialists who have shown that they deliver efficient, effective care, which can lead to speedier recoveries, fewer complications, and fewer repeat procedures.

SIMPLIFYING ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEXITY

Robin J. Thomashauer, M.H.S.A.

Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare

Recent studies estimate that between $30 billion and $33 billion of unnecessary costs can be extracted from the healthcare industry specifically by automating administration, which is still predominantly a manual and paper-based system (Goldstein, 2009; U.S. Healthcare Efficiency Index, 2009). Industry collaboration addressing the use of electronic administrative data are significantly reducing administrative burden for both payers and providers in several areas. These efforts have sparked renewed interest within the national dialogue on health reform.

The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare, a nonprofit healthcare industry alliance that is helping drive payer collaboration and process consolidation through national, multistakeholder initiatives, is engaged in two initiatives that are producing real results in the marketplace today: the Committee on Operating Rules for Information Exchange (CORE) and the Universal Provider Datasource (UPD). This paper provides an overview of UPD and CORE as two examples of effective industry collaboration with a special focus on a recent study of the actual cost savings, benefits, and national implications of CORE certification.

Universal Provider Datasource (UPD)

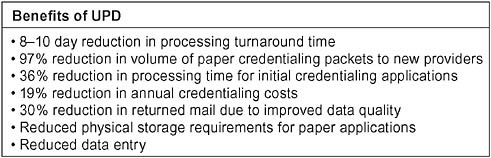

UPD replaces multiple organization-specific paper processes with a single uniform system for the collection of provider data that is used for a wide range of purposes including credentialing and provider directories. Through a secure, centralized online service, the system has already reduced the administrative costs associated with credentialing healthcare provid-

ers by almost $90 million per year and eliminated more than 2.3 million legacy paper applications. Participating organizations report significant increases in the efficiency of numerous processes, including outreach to providers, data entry, application storage, and application turnaround time (Figure 11-3). UPD is used by over 745,000 providers and more than 500 public and private organizations throughout the United States, with enrollment increasing by approximately 8,000 providers per month. Use of the data is authorized only by the individual provider. Currently, 12 states have adopted the Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare Uniform Provider Credentialing application as their state standard. The initiative has received strong and broad-based industry support from America’s Health Insurance Plans, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Health Information Management Association, American Medical Association, Medical Group Management Association, Healthcare Administrative Simplification Coalition, and others.