12

Community-Based and Transitional Care

INTRODUCTION

Given the significant dependence of health status on the dynamics of physical, behavioral, and social determinants (WHO, 2009), community-based and transitional care initiatives represent opportunities to improve health through investments in population and public health. Yet, only approximately 6.4 percent of national health expenditures is spent on public and population health (CMS, 2009). Speakers participating in this session identify the critical role prevention and population health as well as quality and consistency in treatment, with a focus on the medically complex, could play in lowering the burden of chronic illness and improving productivity and quality of life.

Kenneth E. Thorpe of Emory University explains the growing need and proliferation of chronic disease management programs as well as greater opportunities for prevention, better care, and long-run cost savings. Whereas the medical home concept has addressed these needs for larger practices, Thorpe offers community health teams (CHTs) as a more viable approach for smaller practices. CHTs include care coordinators, nutritionists, behavioral and mental health specialists, nurses and nurse practitioners, and social, public health, and community health workers. Whereas these trained resources already exist in many communities, working with home health agencies, hospitals, health plans, and community-based health organizations, he suggests that a CHT’s added benefit lays in coordination of these resources in the interest of addressing transitional care, palliative care, and prevention services.

Diane E. Meier of Mt. Sinai Medical Center builds on the idea of patient-centered care, describing the growing need for more robust palliative care programs. Reviewing the evidence, she relates that palliative care has been demonstrated to relieve physical and emotional distress; improve patient–family–professional communication and informed, patient-centered decision making; and coordinate and sustain care across the many transitions experienced by patients with complex chronic and serious illness. Meier posits that palliative care not only responds to the needs of this growing population of patients, but translates into better quality care and cost savings. Taken to a national scale, she suggests that palliative care could save $6 billion annually.

In his paper, Jeffrey Levi of Trust for America’s Health presents the organization’s collaboration with the Urban Institute, which focuses on developing an economic model that demonstrates the impact of certain community-based prevention programs targeting chronic diseases on healthcare costs. Based on their analysis, he reports that an investment of $10 per person per year in proven community-based programs to increase physical activity, improve nutrition, and prevent smoking and other tobacco use could save the country more than $16 billion annually within 5 years—a return of $5.60 for every $1 invested. Levi acknowledges that these estimates do not reflect the costs of implementation. He additionally notes a paradigm shift in the commitment to prevention efforts, reflected by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 investment of $650 million to introduce community-based prevention programs and study their impacts.

COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAMS: OUTCOMES AND COSTS

Kenneth E. Thorpe, Ph.D., and Lydia L. Ogden, M.A., M.P.P.

Emory University

The rising rate of diagnosed and treated chronic diseases, many associated with obesity, is a key factor in rising U.S. healthcare spending (Table 12-1) (Thorpe and Howard, 2006). Patients with chronic disease are estimated to account for 75 percent of overall health spending (CDC, 2008) and 99 percent of Medicare spending (Partnership for Solutions National Program Office, 2004). Multiple morbidities are common: more than half of Medicare beneficiaries are treated for five or more chronic conditions yearly (Thorpe and Howard, 2006). Six chronic ailments account for 40 percent of the recent rise in Medicare spending (Thorpe and Howard, 2006). Despite significant healthcare outlays, chronically ill patients receive just 55 percent of clinically recommended services (McGlynn et al., 2003), and that gap in care may explain a nontrivial portion of morbidity and mortality.

TABLE 12-1 Treated Chronic Disease Prevalence by Body Mass Index (BMI) for Top 10 Health Conditions, Medicare Beneficiaries, 1987, 1997, and 2006

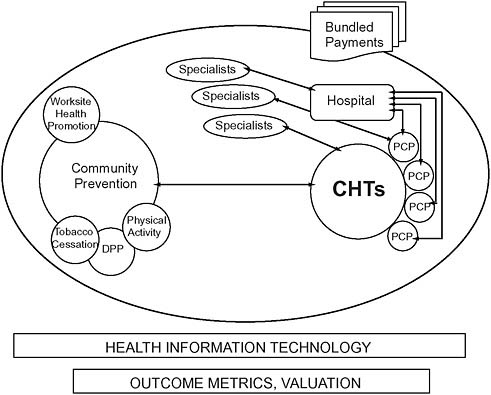

In response, chronic disease management programs have proliferated over the past decade in the private sector and are common in Medicaid and Medicare Advantage programs. But they are notably absent in traditional fee-for-service Medicare—a crucial gap, given that 81 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in traditional fee-for-service Medicare and account for about 79 percent of the program’s overall healthcare spending (Orszag, 2007). The Medicare program’s fragmented benefit design and reimbursement policies discourage care coordination and disease management. At the same time, these conditions present opportunities for prevention, better care, and long-run cost savings (CBO, 2005). The medical home concept developed by the National Committee on Quality Assurance has attracted attention and interest as a potential solution, but it has limited scalability among the 83 percent of U.S. medical practices that comprise just one or two physicians (GAO, 2008; Sokol et al., 2005). An alternative (and complementary) approach is required to scale coordinated care nationwide. CHTs working with primary care practices, patients, and their families apply key functions and processes used by larger successful physician group practices and integrated plans and replicate them in less resourced and organized settings (Figure 12-1). CHTs include care coordinators, nutritionists, behavioral and mental health specialists, nurses and nurse practitioners, and social, public health, and community health workers. These trained resources already exist in many communities, working for home health agencies, hospitals, health plans, and community-based health organizations.

Evidence of Effectiveness and Cost Savings

Research supports the clinical and economic benefits of comprehensive, multidisciplinary, individualized interventions targeted to medically complex patients. Evidence-based components of CHT practice elements are listed in Table 12-2.

CHTs should include a number of critical foci in order to better address current healthcare needs and control financial costs. Four are discussed below.

Prevention services Taking lessons from the large-scale, randomized diabetes prevention program (DPP) (Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Knowler et al., 2002; Wing et al., 2004)1 trials, group-based DPP protocols have been administered in community settings and have produced impressive outcomes, reducing disease incidence at a fraction of

FIGURE 12-1 Intersectoral collaboration: Community health teams.

NOTE: CHT = community health team; DPP = diabetes prevention program; PCP = primary care providers.

SOURCE: Thorpe, 2009.

the cost of clinical intervention (Ackermann and Marrero, 2007). A broader investment of $10/person/year in community-based prevention could yield more than $16 billion in medical cost savings within 5 years (Levi et al., 2008). Indirect cost savings derived from preventing just the top seven chronic conditions could be four times higher, adding another $64 billion (DeVol et al., 2007).

Transitional care Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has estimated that 18 percent of all hospital stays result in a readmission within 30 days, costing $15 billion annually. Approximately $12 billion is spent on potentially avoidable readmissions (Miller, 2008). A recent analysis by Jencks and colleagues reports that nearly 20 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted after an index hospital stay within 30 days and 34 percent within 90 days, costing $17.4 billion in 2004 (Jencks et al., 2009). Recent research from the University of Pennsylvania showed a

TABLE 12-2 Evidence-Based Components of CHT Practice Elements

|

Components |

Sources |

|

Targeting the right patients |

Brown, 2009; Meyer and Smith, 2008; Peikes et al., 2009 |

|

Close integration |

GAO, 2008; Meier, 2009; Morrison et al., 2008; Naylor et al., 2004 |

|

Medication and testing adherence |

McDonald et al., 2002; Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005; Sokol et al., 2005 |

|

Transitional care programs |

Naylor, 2003; Naylor et al., 1994, 1999; Norton et al., 2007 |

|

Palliative care programs |

Elsayem et al., 2004; Meier, 2009; Morrison et al., 2008; Norton et al., 2007 |

|

Ability to link with and refer to effective community-based interventions |

Ackermann and Marrero, 2007; Fielding and Teutsch, 2009; Lurie and Fremont, 2009 |

|

Real-time evaluation and information on clinical markers with feedback |

Fielding and Teutsch, 2009; Lurie and Fremont, 2009; Morrison et al., 2008 |

|

Individualized care plans developed with patients, families, and primary providers |

Boyd et al., 2008; Elsayem et al., 2004; Sylvia et al., 2008 |

|

Frequent contact with patients (and families) involving education, reminders, coaching, and self-management support |

CMS, 2003; Elsayem et al., 2004; Esposito et al., 2009 |

56 percent reduction in readmissions and 65 percent fewer hospital days for frail elders in transitional care. At the 12-month mark, average costs were $4,845 lower for these patients (Naylor et al., 2004). If this model were scaled nationally with a 10-year investment of $25 billion, savings could reach $100 billion over the same period.

Medication adherence Medication adherence is 50 to 65 percent for common chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes (Sherman et al., 2009), and nonadherence is costly, reaching $100 billion/year for hospitalizations alone (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). Primary care providers and CHTs must implement proven strategies to increase adherence: patient education, improved dosing schedules, improved communication between providers and patients, and expanded access through additional clinic hours and/or electronic communication (McDonald et al., 2002; Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). Studies have shown that increased adherence posts a substantial return on investment; for example: 7:1 for diabetes, 5.1:1 for hyperlipidemia, 3.98:1 for hypertension; and a reduction in overall healthcare spending of 15 percent for patients with chronic heart failure (Esposito et al., 2009; Sokol et al., 2005).

Palliative care Spending for beneficiaries in their last year of life is nearly six times more than for those who are not in their last year of life (about a quarter of Medicare outlays). Expenditures rapidly accelerate in the last few months of life, a result of inpatient hospitalizations. In the last month of life, expenditures are 20 times higher than for other beneficiaries (CMS, 2003). Increasing the uptake of palliative care services to just 7.5 percent of hospital discharges (from the current level of 1.5 percent) could save more than $37 billion over 10 years2 and improve quality of life for patients with advanced illness (Zhang et al., 2009).

Funding and Financial Incentives

Making CHTs available to all beneficiaries enrolled in traditional fee-for-service Medicare would cost $1 billion annually in federal grants.3 Because reimbursement for crucial elements of effective chronic disease management—education, patient counseling, care coordination, and patient monitoring—is limited in fee-for-service Medicare, payment reforms assume a powerful role in incentivizing the adoption of CHTs and the development of accountable health teams that also include hospitals and specialists. At least three potential payment reforms would provide strong incentives to move toward these integrated approaches and reduce some of the well-publicized problems with Medicare’s current fee-for-service payment system.

Primary care reimbursements Medicare payment policy must change to reward coordinated care. A straightforward mechanism is a supplemental per person per month (PPPM) payment for physician practices that establish a formal relationship with a CHT. PPPM payments should increase as the practice successfully incorporates evidence-based components of the patient-centered medical home. Additional financial assistance should support the acquisition and implementation of electronic medical records.

Bundled payments Coordinated, accountable care can also be encouraged through bundled hospital payments, starting with seven high readmission Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) identified

by MedPAC4 (2007) and, within a 3- to 5-year period, extending to all Medicare admissions. Payments would cover all acute services for the MS-DRG admission, and Medicare covered post-acute (30 days after discharge) spending. Hospitals with above-average readmission rates would receive reduced payments for patients readmitted within the 30-day period. This approach would create strong incentives for hospitals to contract with CHTs to focus on transitional care. The National Quality Forum is working to develop consensus measures focused on preventable hospital readmissions (National Quality Forum, 2006).

Bonus pools Incentives for improving health outcomes and reducing unnecessary care are an essential element of integrated care. Physicians and CHT staff should be eligible for additional payments if key performance measures are met. In addition to preventable readmissions, other quality measures should include improvement in clinically recommended services for common and costly chronic illnesses. To be eligible for bonus payments, health teams would have to meet a three-part test: First, Medicare per capita spending in the hospital service/referral area (as defined by the states in establishing the CHTs) would have to be lower than an established benchmark amount (lower than the average annual per capita growth for the prior 2 to 3 years). Second, readmissions for the seven MedPAC tracer hospital conditions would have to decline. Third, quality measures (starting with the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set [HEDIS] measures for managing and treating diabetes, hypertension, and other targeted conditions) would have to improve.

Next Steps

To scale CHTs nationally, they should be implemented in the Medicare program within 3 years, supported by federal funds flowing to state governments, which would create CHTs tied to hospital referral areas within or between states. Services within and outside the traditional health system should be covered—integrating public health and primary prevention initiatives (e.g., diet, exercise, weight loss, smoking cessation) with secondary and tertiary prevention (screening, treatment, and care). States could (and should) use CHTs to manage dual eligibles, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, or other patients. Self-insured firms and private health plans could (and should) contract with CHTs to manage medically complex patients and at-risk clients. Payment reforms that support and promote coordinated care and lower volume of services should encompass changes

in physician reimbursements, bundled payments, and bonus pools. In addition, patients actively engaged in following their care plan (per their care coordinator) should receive all clinically indicated preventive services and generic drugs (or discounts for the use of brand-name drugs without a generic alternative) with no cost sharing. Improving chronically ill patients’ care and health outcomes and reducing healthcare cost growth are intertwined. Each is essential to health reform in the United States. CHTs are a means to those ends and should be an integral part of a changed system.

PALLIATIVE CARE, QUALITY AND COSTS

Diane E. Meier, M.D., FACP, Jessica Dietrich, M.P.H., R. Sean Morrison,

M.D., Mount Sinai School of Medicine; and Lynn Spragens, M.B.A

Spragens & Associates

Palliative care programs in hospitals are a rapidly diffusing innovation (Goldsmith et al., 2008) and have been shown to both improve quality and reduce costs of care for America’s sickest and most medically complex patients (Anderson, 2007; Back et al., 2005; Brumley et al., 2007; Carlson et al., 1988; Elsayem et al., 2004; Morrison et al., 2008; Penrod et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). The chronically and seriously ill constitute only 5 to 10 percent of patients but account for well over half of the nation’s healthcare costs (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009; Potetz and Cubanski, 2009; Seow et al., 2009). Palliative care programs are a solution to this growing quality and cost crisis.

What Is Palliative Care?

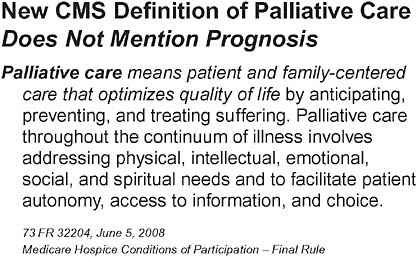

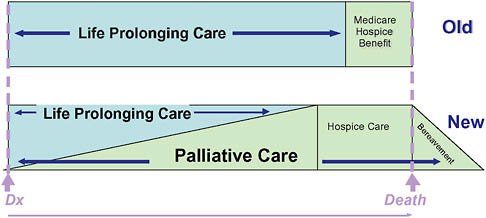

Palliative care is medical care focused on relief of pain and other sources of suffering for patients with advanced illness and their families. It is appropriate at any point in a serious illness, whether the patient is expected to fully recover, will live for years with chronic illness, or is subject to progressive decline up to the time of death. Unlike hospice, palliative care is not prognosis driven, and eligibility depends strictly on need and likelihood of benefit (Figure 12-2). In contrast, hospice is a form of palliative care covered by a special insurance benefit restricted to patients with a prognosis of 6 months or less who agree to forego insurance coverage of curative or life-prolonging treatments (Figure 12-3).

Yet, until recently, palliative care services were typically available only to patients enrolled in hospice. Now, palliative care programs are increasingly found in hospitals—the main site of care for the seriously ill and site of death for 50 percent of adults on average nationwide (Brown University Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, 2001). As of 2006, 53 percent of U.S. hospitals and 75 percent of hospitals with more than

FIGURE 12-2 New CMS definition of palliative care.

SOURCE: Medicare Hospice Conditions of Participation—Final Rule. 73 FR 32204, June 5, 2008.

300 beds reported the presence of a palliative care program—an increase of 97 percent from 2000 (American Hospital Association, 2009; Goldsmith et al., 2008). Palliative medicine is now an American Board of Medical Specialties-approved subspecialty with 10 parent boards and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has certified the first 55 postgraduate fellowship training programs (American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2009) to develop the workforce necessary to meet

FIGURE 12-3 Conceptual shift for palliative care.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the National Consensus Project. NCP, 2004.

the nation’s needs (Casarett, 2000; Portenoy et al., 2006; Scharfenberger et al., 2008; Scott and Hughes, 2006; von Gunten, 2006).

As outlined by the National Quality Forum (2006) and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2004), the essential structural elements of hospital palliative care include an interdisciplinary team of clinical staff (physician, nurse, and social worker); staffing ratios determined by hospital size; staff trained, credentialed, and/or certified in palliative care; and access and responsiveness 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. These elements are designed to focus on better outcomes for patients through relief of physical and emotional distress; improved patient–family–professional communication and informed, patient-centered decision making; and coordination and continuity of care across the many transitions experienced by patients with complex chronic and serious illness (Morrison and Meier, 2004; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2004; National Quality Forum, 2006).

Why Palliative Care?

Despite enormous expenditures, studies demonstrate that patients with serious illness and their families receive poor quality medical care characterized by untreated symptoms, unmet personal care needs, high caregiver burden, and low patient and family satisfaction (Field and Cassel, 1997; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005, 2009; Teno et al., 2004; Thorpe and Howard, 2006). Of the $426 billion spent by Medicare in 2008, 30 percent ($128 billion) was spent on acute care (hospital) services. A very small proportion—10 percent—of the sickest Medicare beneficiaries account for fully 63 percent of total program spending, at more than $44,220 per capita per year (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005, 2009).

How Does Palliative Care Reduce Costs?

Palliative care programs target the cost drivers that lead to increased use of hospitals, specialists, and procedures, and promote delivery of coordinated, communicated, patient-centered care. This is done in the following ways:

-

These programs address pain and symptoms that increase hospital complications and lengths of stay.

-

Palliative care teams meet with patients and families to establish clear care goals.

-

Treatments are reviewed to align with those goals, and those that do not meet them are not initiated or suspended.

-

Patients and their teams develop comprehensive discharge plans.

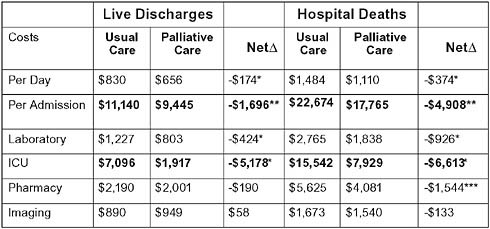

This coordinated effort in palliative care programs reduces hospital costs, readmissions, and emergency department visits. Costs go down because fewer deaths occur in the hospital as a consequence of better family support, care coordination, and home care and hospice referrals; more admissions go directly to the palliative care service instead of a high-cost ICU bed; patients not benefiting from an ICU setting are transferred to more appropriate and lower-intensity settings; and nonbeneficial or futile imaging, laboratory, specialty consultation, and procedures are avoided (Figure 12-4). Controlled trials in Europe (Higginson et al., 2002; Jordhoy et al., 2000) and multisite studies in the United States suggest that the savings associated with palliative care can be substantial (Anderson, 2007; Back et al., 2005; Brumley et al., 2007; Carlson et al., 1988; Elsayem et al., 2004; Gomes et al., 2009; Harding et al., 2009; Higginson, 2009; Higginson and Foley, 2009; Morrison et al., 2008; Penrod et al., 2006; Smith and Cassel, 2009; Smith et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2007; Wright et al., 2008).

Impact of Palliative Care on Annual Healthcare Costs

Based on recent data (Morrison et al., 2008), the per-patient costs saved by palliative care consultation are $2,659. Approximately 2 percent

FIGURE 12-4 Hospital palliative care reduces costs: Cost and intensive care outcomes associated with palliative care consultation in eight U.S. hospitals.

aP < .001.

bP < .01.

cP < .05.

SOURCE: Morrison, R. S., J. D. Penrod, J. B. Cassel, M. Caust-Ellenbogen, A. Litke, L. Spragens, and D. E. Meier. 2008. Cost savings associated with U.S. hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med 168(16):1783-1790. Copyright 2008. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

of all 30,181,406 annual hospitalizations in the United States end in death (AHRQ, 2002). Assuming that palliative care programs should be seeing most patients who die in the hospital, plus the approximately triple this number of hospitalized patients with advanced and complex chronic illness who are discharged alive (Siu et al., 2009), at scale, palliative care programs should be seeing more than 5 to 8 percent of all hospital discharges (patients who die plus very sick patients discharged alive). At present (2009) palliative care programs exist in 53 percent of U.S. hospitals (Goldsmith et al., 2008), and penetration reaches approximately 1.5 percent of all discharges, translating only to about $1.2 billion in avoided costs annually.5 Once access to palliative care is at scale (when more than 90 percent of U.S. hospitals have a program reaching at least 7.5 percent of discharges), annual costs can save approximately $6 billion (Goldsmith et al., 2008; Morrison et al., 2008; Siu et al., 2009).

How Does Palliative Care Improve Quality?

Palliative care programs improve physical and psychological symptoms, family caregiver well-being, and patient, family, and consulting physician satisfaction (Casarett et al., 2008; Elsayem et al., 2004; Fallowfield and Jenkins, 2004; Fellowes et al., 2004; Higginson et al., 2003; Jordhoy et al., 2000, 2001; Lilly et al., 2000; Manfredi et al., 2000; Morrison et al., 2003; Rabow et al., 2004; Ringdal et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2002). Employing interdisciplinary teams of physicians, nurses, social workers, and additional personnel when needed (chaplains, physical therapists, psychologists, and others), palliative care teams identify and rapidly treat distressing symptoms that have been independently shown to increase medical complications and hospital use (Jordhoy et al., 2000; Manfredi et al., 2000; Morrison et al., 2003, 2009). Palliative care teams meet extensively with patients and their families to establish appropriate and realistic goals, support families in crisis, and plan for safe transitions out of hospitals to lower-intensity settings (home care, hospice, nursing home care with hospice, or inpatient hospice care). Communication about prognosis and patient goals by a dedicated team with time and expertise leads to decision making, clarity of the care plan, and consistent follow-through. Such discussions demonstrably reduce costs and improve family satisfaction and bereavement outcomes (Wright et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Finally, because of the assistance that they provide to already time-pressured physicians, palliative care programs are valued and used by referring physicians.

Assuring Access to Quality Palliative Care for All Americans in Need

Palliative care as a growing innovation holds much more than the promise of cost savings among the highest need and most expensive patients in the healthcare system. Most significantly, this form of care provides for better quality care for those patients most in need of broad-based support during very difficult battles with illness. Even so, palliative care still faces significant challenges in reaching all Americans with advanced or serious illness. Variability in access to palliative care based on geographic location, hospital size, and ownership limit access to palliative care (Billings and Block, 1997; Goldsmith et al., 2008). Lack of physician and nursing education (Billings and Block, 1997; Weissman and Block, 2002; Weissman and Blust, 2005; Weissman et al., 1999) and inadequate compensation and loan forgiveness opportunities to attract young professionals into the field translate into fewer team members qualified to deliver these coordinated services. Financial disincentives discouraging workforce development and organizational commitment, lack of regulatory and accreditation requirements for quality palliative care across healthcare settings, and lack of an evidence base guiding quality care (Gelfman and Morrison, 2008) represent additional barriers to the broad-based availability of palliative care.

In response, three categories of policies aimed at increasing access to quality palliative care have emerged in the United States: (1) workforce; (2) research to build the evidence base necessary for quality care; and (3) financial and regulatory incentives for healthcare organizations and providers across the continuum to develop and sustain access to quality palliative care services (Table 12-3). As the national focus on healthcare reform continues, attention to expanding access to palliative care is a priority, because it is targeting not only the most expensive patients to care for but those most in need of higher-quality services.

COMMUNITY PREVENTION AND HEALTHCARE COSTS

Jeffrey Levi, Ph.D.

Trust for America’s Health

In July 2008, Trust for America’s Health contracted with the Urban Institute to assess the effect on healthcare costs of certain proven community-based prevention programs that targeted some of the most expensive chronic diseases. As detailed in Prevention for a Healthier America: Investments in Disease Prevention Yield Significant Savings, Stronger Communities, we found that a small strategic investment in disease prevention could result in significant savings in U.S. healthcare costs and improvement in outcomes.

We found that many effective prevention programs cost less than $10

TABLE 12-3 Policies to Improve Access to Quality Palliative Care

|

Improve Access to Palliative Care |

|

1. Workforce Physician workforce capacity

Educational and training capacity

Offer incentives through educational loan forgiveness for physicians and advance practice nurses to enter the field. |

|

2. Financial and regulatory incentives for delivery of palliative care services for hospitals, nursing homes, and providers receiving Medicare or Medicaid payments.

|

|

Improve Quality of Palliative Care |

|

1. Health professional training and certification

|

|

2. Research to strengthen the evidence base

|

per person annually, and these programs have succeeded in lowering rates of diseases that are related to physical activity, nutrition, and smoking. The evidence shows that implementing these programs in communities reduces rates of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure by 5 percent within 2 years; reduces heart disease, kidney disease, and stroke by 5 percent within 5 years; and reduces some forms of cancer, arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by 2.5 percent within 10 to 20 years (Trust for America’s Health, 2008). And the financial benefits are just as impressive: an investment of $10 per person per year in proven community-based programs to increase physical activity, improve nutrition, and prevent smoking and other tobacco use could save the country more than $16 billion annually within 5 years—a return of $5.60 for every $1 invested.

The Policy Context

The discussion about prevention efforts in health care has been focused away from the financial implications and much more on the health benefits to people. In fact, it is common knowledge that many prevention efforts in fact do not save money, even though they have impressive health outcomes. Despite this focus in public health circles, the national debate is one that necessitates consideration of cost and dollars saved. To that end, we focused on certain types of conditions and interventions that would actually yield a positive return on investment. In so doing, we hoped to demonstrate that prevention can make sense in terms of dollars and in terms of health outcomes. Furthermore, we want to push the healthcare discussion from inside the four walls of the clinic to what is happening in communities. The high-cost conditions that plague the healthcare system can be effectively addressed through supporting healthy communities, and those prevention efforts will cost far less than addressing the problems after disease has set in.

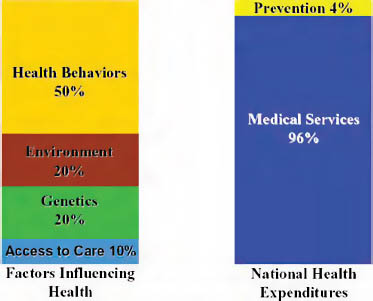

While discussions of healthcare coverage are critical, achieving good health outcomes requires healthy communities, not just healthy individuals. What precedes healthcare coverage and clinical intervention is just as important, especially since the primary drivers of health are in people’s homes and in their communities. Health behaviors and environment drive 70 percent of patient health, yet as a country, we spend less than 5 percent on prevention efforts that would target these areas directly (CDC, 2000) (Figure 12-5).

But as we focus on community-based solutions, we are quickly struck by the relationship between disparities in chronic diseases and disparities in the health of communities. Unfortunately, those same poor communities where we see such high-cost health care are also least equipped to support healthy lifestyles. If you are told to eat healthily and you live in a

FIGURE 12-5 Imbalance of spending.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Blue Sky Initiative, adapted from University of California at San Francisco, Institute of the Future.

neighborhood that does not have a supermarket, this limits your ability to eat healthily regardless of your desire to do so. If your doctor prescribes walking as exercise, you will have difficulty if you live in a neighborhood that does not have sidewalks or where the streets are unsafe. So, even as we discuss the implications of community-based prevention efforts, the issues here are complex and far reaching, and they require an investment commensurate with the role of communities in driving health.

What Is Community-Based Prevention?

Community-based prevention can take many forms, which makes understanding these efforts as part of healthcare reform challenging. This study was based on a systematic review of the literature conducted by the New York Academy of Medicine. Examples of the types of programs that reflect this community-based approach include:

-

Shape Up Somerville: School food, school activities, parent and community outreach, restaurants, safe routes to school.

-

Healthy Eating Active Communities (HEAC): Schools, after school, neighborhoods, healthcare sector, marketing changes.

-

YMCA Pioneering Healthier Communities: Community coalitions, policy changes, leverage other funding.

What these efforts share is that they are community based, they leverage existing resources in their communities toward supporting healthy behaviors and healthy environments, and they are employing evidence-based prevention practices.

The Research Effort

In the economic model developed for this report, we focused on those diseases that were expensive, chronic, and most amenable to community-based prevention. In looking at the interventions themselves, we studied the types of intervention, their effects on disease, and their associated costs. The data for this study came from a literature review and the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), pooled from 2003-2005. While the literature supports that community-based interventions can have an impact of 10 percent on negative health outcomes, we modeled conservatively at 5 percent. Similarly, the data regarding per capita costs were widely variable, so we chose a conservative estimate of a cost of $10 per capita for these interventions. Unfortunately, one of the challenges we faced during the research was the wide variation in quality of studies and in information available about the prevention efforts themselves, their costs, and their impacts.

Community-Level Interventions Can Reduce Chronic Disease Levels

Again, the findings from the research are groundbreaking. Regardless of chronic condition targeted, most interventions targeted fell into four categories: physical activity, nutrition, obesity, and smoking cessation. In each case, the community-based prevention efforts reduced or delayed the incidence of disease. The current healthcare system focuses on management of disease or disability, but here, primary prevention delays or prevents disease or disability all together. These findings are more significant when you consider that these chronic diseases have not been found to shorten life, only to make a larger proportion of life under the influence of disease. While some suggest that prolonging life is only pushing costs into the future, there is growing evidence to support the compression of morbidity—the extension of healthy life expectancy rather than the extension of total life expectancy by compressing chronic disease and disability into a smaller proportion of life. Thus there is a potential net savings in healthcare costs even as life is extended.

Related to this report’s findings, the need for prevention efforts will only continue to grow. Trust for America’s Health just released its annual obesity report, where we found that, on average, among the 55 to 64 age cohort, the obesity rates are 10 percent higher than the current 65 and older age cohort. The opportunity is ripe for prevention efforts aimed at

this 55 to 64 cohort to obviate some of the high costs of obesity-related disease that we will certainly be seeing as they age into retirement and go onto Medicare.

The Numbers

Again, an investment of $10 per person per year in proven community-based programs to increase physical activity, improve nutrition, and prevent smoking and other tobacco use could save the country more than $16 billion annually within 5 years—a return of $5.60 for every $1 invested. Out of the $16 billion, Medicare could save more than $5 billion; Medicaid could save more than $1.9 billion; and private payers could save more than $9 billion within 5 years (Table 12-4). Within 10 to 20 years, the United States could recoup more than $18 billion, a return on investment of $6.20 for every $1 (Table 12-5).

Caveats and Limitations

The estimates generated are likely to be conservative. As noted above, the model assumes costs in the higher range and benefits in the low range. Furthermore, the model does not take into account any costs of institutional care. Chronic disease often leads to disability or frailty that may necessitate

TABLE 12-4 Net Savings by Payer: 5 Percent Impact at $10 per Capita Cost (in 2004 dollars)

|

|

1-2 Years |

5 Years |

10-20 Years |

|

Medicare |

$487 million |

$5.213 billion |

$5.971 billion |

|

Medicaid |

$370 million |

$1.951 billion |

$2.195 billion |

|

Private Payers/Out of Pocket |

$1.991 billion |

$9.380 billion |

$10.285 billion |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Trust for America’s Health, 2008. |

|||

TABLE 12-5 Net Savings: 5 Percent Impact at $10 per Capita Cost (in Millions) (in 2004 dollars)

nursing home care, so exclusion of these costs may underestimate the return on investment in reduction of disease.

While the model is still being elaborated to address many of these issues, limitations of the model as reported here include the following:

-

The model assumes a sustained reduction in the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension over time. The literature on the duration of the effects of intervention is small, with effects usually reported over no more than 3 to 5 years.

-

The model assumes a steady-state population. This model is based on current disease prevalence and does not take into account trends in prevalence. For example, diabetes is increasing while heart disease is declining, but the model estimates savings based on the current prevalence.

-

While the model does take into account competing morbidity risks, it does not take into account changes in mortality. However, in the short (1 to 2 years) and medium run (5 years), changes in mortality are likely to be small.

-

The model calculates all savings in 2004 dollars. Thus, it does not take into account any rise in medical care expenditures or changes in medical technology.

-

The model incorporates only the marginal cost of the interventions and does not reflect the cost of the basic infrastructure required to implement such programs.

-

The intervention effects do not account for variations in community demographics such as distribution of race/ethnicity, age, gender, geography, or income. The intervention effect is treated as constant across groups.

Conclusion

These findings have already translated into healthcare policy reform. The stimulus bill invested $650 million to introduce community-based prevention programs and study their impacts. Even so, the paradigm shift is significant. To paraphrase the President, we want to reach people before they set foot in a doctor’s office. However, the community prevention programs that make that possible push the understanding of many about what healthcare interventions are. Representatives in both houses of Congress have raised questions about the “amorphous” definitions of these prevention programs. After all, these efforts are not about buying medicine or introducing a new clinical treatment, so how can they be real? How can they make a difference in healthcare spending and in real health outcomes for Americans? But with this report and the growing consensus around evidence-based, targeted investment in prevention, the viewpoints of many

of these policy makers and advocates have started to shift. The evidence is there, and it is growing, but we still face many challenges.

REFERENCES

Ackermann, R. T., and D. G. Marrero. 2007. Adapting the Diabetes Prevention Program life-style intervention for delivery in the community: The YMCA model. Diabetes Education 33(1):69, 74-65, 77-68.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2002. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Hospitalization in the United States. http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbk6/factbk6c.htm (accessed August 9, 2009).

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2009. Fellowship accreditiation. http://www.aahpm.org/fellowship/accreditation.html (accessed August 5, 2009).

American Hospital Association. 2009. AHA Hospital Statistics. http://www.aha.org/aha/resource-center/Statistics-and-Studies/index.html (accessed August 2009).

Anderson, G. 2007. Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Back, A. L., Y. F. Li, and A. E. Sales. 2005. Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Journal of Palliative Medicine 8(1):26-35.

Billings, J. A., and S. Block. 1997. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education: Status report and future directions. Journal of the American Medical Association 278(9):733-738.

Boyd, C. M., E. Shadmi, L. J. Conwell, M. Griswold, B. Leff, R. Brager, M. Sylvia, and C. Boult. 2008. A pilot test of the effect of guided care on the quality of primary care experiences for multimorbid older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(5):536-542.

Brown, R. 2009. The Promise of Care Coordination: Models that Decrease Hospitalizations and Improve Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Illness. Mathematics Policy Research. http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/aug2001/niddk-08.htm (accessed August 27, 2010).

Brown University Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research. 2001. Atlas of dying. http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/2001DATA.HTM (accessed August 2009).

Brumley, R., S. Enguidanos, P. Jamison, R. Seitz, N. Morgenstern, S. Saito, J. McIlwane, K. Hillary, and J. Gonzalez. 2007. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 55(7):993-1000.

Carlson, R. W., L. Devich, and R. R. Frank. 1988. Development of a comprehensive supportive care team for the hopelessly ill on a university hospital medical service. Journal of the American Medical Association 259(3):378-383.

Casarett, D. J. 2000. The future of the palliative medicine fellowship. Journal of Palliative Medicine 3(2):151-155.

Casarett, D., A. Pickard, F. A. Bailey, C. Ritchie, C. Furman, K. Rosenfeld, S. Shreve, Z. Chen, and J. A. Shea. 2008. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? Journal of the American Geriatric Society56(4):593-599.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2005. High-Cost Medicare Beneficiaries, CBO Paper. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/63xx/doc6332/05-03-MediSpending.pdf (accessed 2009).

CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention). 2000. Blue Sky Initiative. University of California at San Francisco.

——. 2008. Chronic Disease Overview. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm (accessed July 30, 2009).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2003. Last Year of Life Expenditures. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/mcbs/downloads/issue10.pdf (accessed November 2, 2009).

——. 2009. National Health Expenditure Data Overview. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/national healthexpenddata/01_overview.asp (accessed June 1, 2009).

Department of Health and Human Services. 2001. Press release: Diet and exercise dramatically delay type 2 diabetes, diabetes medication Metformin also effective.

DeVol, R., A. Bedroussain, A. Charuworn, K. Chatterjee, I. K. Kim, and S. Kim. 2007. An unhealthy America: The economic burden of chronic disease charting a new course to save lives and increase productivity and economic growth. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute.

Elsayem, A., K. Swint, M. J. Fisch, J. L. Palmer, S. Reddy, P. Walker, D. Zhukovsky, P. Knight, and E. Bruera. 2004. Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology 22(10):2008-2014.

Esposito, D., A. D. Bagchi, J. M. Verdier, D. S. Bencio, and M. S. Kim. 2009. Medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure: Association of medication adherence with healthcare use and costs. American Journal of Managed Care 15(7):437-445.

Fallowfield, L., and V. Jenkins. 2004. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 363(9405):312-319.

Fellowes, D., S. Wilkinson, and P. Moore. 2004. Communication skills training for health care professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2):CD003751.

Field, M., and C. Cassel. 1997. Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Fielding, J. E., and S. M. Teutsch. 2009. Integrating clinical care and community health: Delivering health. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(3):317-319.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2008. Medicare physician payment: Care coordination programs used in demonstration show promise, but wider use of payment approach may be limited. GAO-08-65.

Gelfman, L. P., and R. S. Morrison. 2008. Research funding for palliative medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11(1):36-43.

Goldsmith, B., J. Dietrich, Q. Du, and R. S. Morrison. 2008. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11(8):1094-1102.

Gomes, B., R. Harding, K. M. Foley, and I. J. Higginson. 2009. Optimal approaches to the health economics of palliative care: Report of an international think tank. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 38(1):4-10.

Harding, R., B. Gomes, K. M. Foley, and I. J. Higginson. 2009. Research priorities in health economics and funding for palliative care: Views of an international think tank. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 38(1):11-14.

Higginson, I. 2009. The Livingston pediatric calculator, revision needed. Emergency Medicine Journal 26(7):544.

Higginson, I. J., and K. M. Foley. 2009. Palliative care: No longer a luxury but a necessity? Journal of Pain Symptom Management 38(1):1-3.

Higginson, I. J., I. Finlay, D. M. Goodwin, A. M. Cook, K. Hood, A. G. Edwards, H. R. Douglas, and C. E. Norman. 2002. Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? Journal of Pain Symptom Management 23(2):96-106.

Higginson, I. J., I. G. Finlay, D. M. Goodwin, K. Hood, A. G. Edwards, A. Cook, H. R. Douglas, and C. E. Normand. 2003. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? Journal of Pain Symptom Management 25(2):150-168.

Jencks, S. F., M. V. Williams, and E. A. Coleman. 2009. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New England Journal of Medicine 360(14):1418-1428.

Jordhoy, M. S., P. Fayers, T. Saltnes, M. Ahlner-Elmqvist, M. Jannert, and S. Kaasa. 2000. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 356(9233):888-893.

Jordhoy, M. S., P. Fayers, J. H. Loge, M. Ahlner-Elmqvist, and S. Kaasa. 2001. Quality of life in palliative cancer care: Results from a cluster randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 19(18):3884-3894.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2005. Analysis of the CMS Medicare current beneficiary survey cost and use file. http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=382 (accessed August 1, 2009).

——. 2009. Health Care Costs: A Primer. http://www.kff.org/insurance/upload/7670_02.pdf (accessed August 1, 2009).

Knowler, W. C., E. Barrett-Connor, S. E. Fowler, R. F. Hamman, J. M. Lachin, E. A. Walker, and D. M. Nathan. 2002. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or Metformin. New England Journal of Medicine 346(6):393-403.

Levi, J., L. M. Segal, and C. Juliana. 2008. Prevention for a healthier America: Investments in disease prevention yield significant savings, stronger communities. http://healthyamericans.org/reports/prevention08/Prevention08.pdf (accessed September 18, 2008).

Lilly, C. M., D. L. De Meo, L. A. Sonna, K. J. Haley, A. F. Massaro, R. F. Wallace, and S. Cody. 2000. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. American Journal of Medicine 109(6):469-475.

Lurie, N., and A. Fremont. 2009. Building bridges between medical care and public health. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(1):84-86.

Manfredi, P. L., R. S. Morrison, J. Morris, S. L. Goldhirsch, J. M. Carter, and D. E. Meier. 2000. Palliative care consultations: How do they impact the care of hospitalized patients? Journal of Pain Symptom Management 20(3):166-173.

McDonald, H. P., A. X. Garg, and R. B. Haynes. 2002. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: Scientific review. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(22):2868-2879.

McGlynn, E. A., S. M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey, J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, and E. A. Kerr. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635-2645.

Meier, D. M. 2009. Palliative care improves quality, reduces costs. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs, Improving Outcomes, July 17, Washington, DC.

Meyer, J., and B. Smith 2008. Chronic disease management: evidence of predictable savings. Health Care Management Associates. http://www.idph.state.ia.us/hcr_committees/common/pdf/clinicians/savings_report.pdf (accessed August 30, 2010).

Miller, M. E. 2008. Report to Congress: Reforming the Delivery System. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Morrison, R., and D. Meier. 2004. Clinical practice: Palliative care. New England Journal of Medicine 350(25):2582-2590.

Morrison, R. S., J. Magaziner, M. A. McLaughlin, G. Orosz, S. B. Silberzweig, K. J. Koval, and A. L. Siu. 2003. The impact of post-operative pain on outcomes following hip fracture. Pain 103(3):303-311.

Morrison, R. S., J. D. Penrod, J. B. Cassel, M. Caust-Ellenbogen, A. Litke, L. Spragens, and D. E. Meier. 2008. Cost savings associated with us hospital palliative care consultation programs. Archives of Internal Medicine 168(16):1783-1790.

Morrison, R. S., S. Flanagan, D. Fischberg, A. Cintron, and A. L. Siu. 2009. A novel interdisciplinary analgesic program reduces pain and improves function in older adults after orthopedic surgery. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 57(1):1-10.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. New York.

National Quality Forum. 2006. A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. Washington, DC.

Naylor, M. 2003. Transitional care of older adults. Annual Review of Nursing Research 20:127-147.

Naylor, M. D., D. A. Brooten, R. L. Campbell, G. Maislin, K. M. McCauley, and J. S. Schwartz. 2004. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 52(5):675–684.

Naylor, M., D. Brooten, R. Jones, R. Lavizzo-Mourey, M. Mezey, and M. Pauly. 1994. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: A randomized clinical trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 120(12):999–1006.

Naylor, M. D., D. Brooten, R. Campbell, B. S. Jacobsen, M. D. Mezey, M. V. Pauly, and J. S. Schwartz. 1999. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 281(7):613-620.

Norton, S. A., L. A. Hogan, R. G. Holloway, H. Temkin-Greener, M. J. Buckley, and T. E. Quill. 2007. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Critical Care Medicine 35(6):1530-1535.

Orszag, P. 2007. The Medicare Advantage Program: Enrollment Trends and Budgetary Effects. Testimony Before U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Washington, DC.

Osterberg, L., and T. Blaschke. 2005. Adherence to medication. New England Journal of Medicine 353(5):487-497.

Partnership for Solutions National Program Office. 2004. Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. http://www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=14685 (accessed 2009).

Peikes, D., A. Chen, J. Schore, and R. Brown. 2009. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. Journal of the American Medical Association 301(6):603-618.

Penrod, J. D., P. Deb, C. Luhrs, C. Dellenbaugh, C. W. Zhu, T. Hochman, M. L. Maciejewski, E. Granieri, and R. S. Morrison. 2006. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(4):855-860.

Portenoy, R. K., D. E. Lupu, R. M. Arnold, A. Cordes, and P. Storey. 2006. Formal ABMS and ACGME recognition of hospice and palliative medicine expected in 2006. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(1):21-23.

Potetz, L., and J. Cubanski. 2009. A Primer on Medicare Financing. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Rabow, M. W., S. L. Dibble, S. Z. Pantilat, and S. J. McPhee. 2004. The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Archives of Internal Medicine 164(1):83-91.

Ringdal, G. I., M. S. Jordhoy, and S. Kaasa. 2002. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 24(1):53-63.

Scharfenberger, J., C. D. Furman, J. Rotella, and M. Pfeifer. 2008. Meeting American Council of Graduate Medical Education guidelines for a palliative medicine fellowship through diverse community partnerships. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11(3):428-430.

Scott, J. O., and L. Hughes. 2006. A needs assessment: Fellowship Directors Forum of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(2):273-278.

Seow, H., C. F. Snyder, L. R. Shugarman, R. A. Mularski, J. S. Kutner, K. A. Lorenz, A. W. Wu, and S. M. Dy. 2009. Developing quality indicators for cancer end-of-life care: Proceedings from a national symposium. Cancer 115(17):3820-3829.

Sherman, B. W., S. G. Frazee, R. J. Fabius, R. A. Broome, J. R. Manfred, and J. C. Davis. 2009. Impact of workplace health services on adherence to chronic medications. American Journal of Managed Care 15(7):e53-e59.

Siu, A. L., L. H. Spragens, S. K. Inouye, R. S. Morrison, and B. Leff. 2009. The ironic business case for chronic care in the acute care setting. Health Affairs (Millwood) 28(1):113-125.

Smith, T. J., and J. B. Cassel. 2009. Cost and non-clinical outcomes of palliative care. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 38(1):32-44.

Smith, T. J., P. S. Staats, T. Deer, L. J. Stearns, R. L. Rauck, R. L. Boortz-Marx, E. Buchser, E. Catala, D. A. Bryce, P. J. Coyne, and G. E. Pool. 2002. Randomized clinical trial of an implantable drug delivery system compared with comprehensive medical management for refractory cancer pain: Impact on pain, drug-related toxicity, and survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology 20(19):4040-4049.

Smith, T. J., P. Coyne, B. Cassel, L. Penberthy, A. Hopson, and M. A. Hager. 2003. A high-volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in-hospital end-of-life care costs. Journal of Palliative Medicine 6(5):699-705.

Sokol, M. C., K. A. McGuigan, R. R. Verbrugge, and R. S. Epstein. 2005. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Medical Care 43(6):521-530.

Sylvia, M. L., M. Griswold, L. Dunbar, C. M. Boyd, M. Park, and C. Boult. 2008. Guided care: Cost and utilization outcomes in a pilot study. Disease Management 11(1):29-36.

Taylor, D. H., Jr., J. Ostermann, C. H. Van Houtven, J. A. Tulsky, and K. Steinhauser. 2007. What length of hospice use maximizes reduction in medical expenditures near death in the U.S. Medicare program? Social Science Medicine 65(7):1466-1478.

Teno, J. M., B. R. Clarridge, V. Casey, L. C. Welch, T. Wetle, R. Shield, and V. Mor. 2004. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(1):88-93.

Thorpe, K. 2009. Delivery reform: The roles of primary and specialty care in innovative new delivery models. http://www.emory.edu/policysolutions/pdfs/kenneththorpe_testimony_ 0509.pdf (accessed November 2009).

Thorpe, K. E., and D. H. Howard. 2006. The rise in spending among Medicare beneficiaries: The role of chronic disease prevalence and changes in treatment intensity. Health Affairs (Millwood) 25(5):w378-w388.

Trust for America’s Health. 2008. Prevention for a Healthy America. http://healthyamericans. org/reports/prevention08/ (accessed August 26, 2009).

von Gunten, C. F. 2006. Fellowship training in palliative medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(2):234-235.

Weissman, D. E., and S. D. Block. 2002. ACGME requirements for end-of-life training in selected residency and fellowship programs: A status report. Acad Med 77(4):299-304.

Weissman, D. E., and L. Blust. 2005. Education in palliative care. Clinical Geriatric Medicine 21(1):165-175, ix.

Weissman, D. E., S. D. Block, L. Blank, J. Cain, N. Cassem, D. Danoff, K. Foley, D. Meier, P. Schyve, D. Theige, and H. B. Wheeler. 1999. Recommendations for incorporating palliative care education into the acute care hospital setting. Academic Medicine 74(8):871-877.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ (accessed October, 2009).

Wing, R. R., R. F. Hamman, G. A. Bray, L. Delahanty, S. L. Edelstein, J. O. Hill, E. S. Horton, M. A. Hoskin, A. Kriska, J. Lachin, E. J. Mayer-Davis, X. Pi-Sunyer, J. G. Regensteiner, B. Venditti, and J. Wylie-Rosett. 2004. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obesity Research 12(9):1426-1434.

Wright, A. A., B. Zhang, A. Ray, J. W. Mack, E. Trice, T. Balboni, S. L. Mitchell, V. A. Jackson, S. D. Block, P. K. Maciejewski, and H. G. Prigerson. 2008. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(14):1665-1673.

Zhang, B., A. A. Wright, H. A. Huskamp, M. E. Nilsson, M. L. Maciejewski, C. C. Earle, S. D. Block, P. K. Maciejewski, and H. G. Prigerson. 2009. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Archives of Internal Medicine 169(5):480-488.