13

Entrepreneurial Strategies

INTRODUCTION

Stemming from innovation’s significant value to the healthcare industry, entrepreneurial strategies to lower costs and improve outcomes, such as telehealth applications and retail clinics have recently emerged, and may have the ability to lower costs and improve outcomes. Technology has facilitated patient self-management at home and remote provider consultations (Cady et al., 2009; Handley et al., 2008; Marziali, 2009). Development of retail clinics and use of community health workers has expanded access to care (AHRQ, 2008; Ballester, 2005). In this final session focusing on strategies that work, the presenters consider entrepreneurial strategies and innovations, offering yet another host of pathways for increasing efficiency, enhancing quality, and containing costs.

Jason Hwang from Innosight applies the concept of disruptive innovation to healthcare delivery, discussing simplifying technologies to enable care by lower-cost providers working in lower-cost settings. Hwang argues that the healthcare system has been moving away from centralized service delivery to a gradually more decentralized system. Increases in outpatient care in ambulatory settings, the rapid expansion of retail clinics staffed by nurse practitioners, and advances in telehealth and home monitoring are some examples of this trend. Hwang offers that opportunity exists for incorporating unlicensed laypeople to assist with care provision. In South America, community health workers, also known as promotores, have played an important part in South America’s model of care, and Hwang

suggests that there is anecdotal evidence of successful use of community health workers across the United States.

N. Marcus Thygeson from HealthPartners provides another example of promising practices from the business world in the form of retail clinics. Introduced in 2000 to deliver a limited set of simple clinical services in a convenient retail setting, retail clinics are typically staffed by mid-level providers with remote physician oversight. As the average cost per episode in a retail clinic is $55 less than in physician offices or urgent care clinics and $279 less than in emergency departments, Thygeson proposes that, if scaled to a national level, these clinics could yield savings as high as $7.5 billion. However, he simultaneously notes that these savings could be lower than predicted given some of the limitations of retail clinics today, including their congregation in urban areas and their narrow field of offered services. The actual savings may also be lower if established providers maintain their revenue by increasing the number of visits per episode for their remaining patients, or charge more for non-retail clinic-eligible services. Even so, he believes that retail clinics may present a provocative competitive force in the healthcare market to encourage lower operational costs and prices to consumers.

Adam Darkins from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) discusses the technological innovation that has dramatically changed health care for thousands of patients served by the VA: home telehealth. While routine outpatient clinic appointments remain the mainstay in managing chronic disease in the United States, he suggests that their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have not been substantiated by comparative effectiveness studies. Patients with chronic conditions usually deteriorate at variable times before or after a routine clinic visit. Darkins suggests that the “just-in-case approach” is outdated and relatively ineffective. Home telehealth devices have been routinely available to continually monitor patients with chronic conditions and transmit vital signs and other disease management data to clinicians remotely located in the hospital and clinic. The VA, in Darkins’ words, has shifted from the just-in-time approach to the just-in-case approach with the implementation of an initiative called care coordination/home telehealth. In addition to better outcomes, such as a 19 percent reduction in hospital admissions and a 25 percent reduction in lengths of stay, the cost savings achieved by the program have been significant. If taken to the national level and assuming that the same level of savings could be achieved in non-VA health systems, Darkins believes that care coordination/home telehealth implementation in targeted areas could translate to cost savings of over $2 billion or between 22 percent and 48 percent of healthcare costs for the target population.

DECENTRALIZING HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Jason Hwang, M.D., M.B.A.

Innosight Institute

Disruptive innovation has been fundamental to lowering the cost of products and services in nearly every industry, and a similar transformation in health care is long overdue. Put succinctly, disruptive innovation employs simplifying technologies to enable healthcare delivery by lower-cost providers working in lower-cost settings. This process corresponds to a gradual decentralization of care delivery, as the provision of care moves away from the legacy system that revolves around centralized institutions of high-cost expertise.

The Centralization of Health Care

In the early twentieth century, several factors led to a consolidation of healthcare delivery in the modern hospital. Advancements in medical technology had made medical care much more complex and expensive, such that only large institutions could afford to own and operate the new diagnostic and life-sustaining equipment. In addition, professional round-the-clock nursing care had demonstrable value and was available to most people only in a hospital setting. At the same time, the practice of medicine was largely dependent upon the intuition of a limited number of well-trained physicians, and most clinical outcomes were the result of their trial-and-error experimentation. Optimizing good outcomes necessitated employing and training many specialists within the same institution, and hospitals became the sole source of solutions to complex medical problems.

In fact, this pattern of consolidated expertise reflects the early stages of many industries, as it represents the optimum way to maximize use of costly and scarce resources when production outcomes remain largely uncertain. However, as hospitals’ capabilities and functions have expanded over time, they have been slow to spin off more routine work to new institutions of care, a process that would typically lower per unit costs.

Nevertheless, an increasing amount of clinical care has been offloaded to less costly providers working in decentralized venues. The trend toward outpatient care in ambulatory settings has existed for decades, but a more recent example is the rapid expansion of retail clinics staffed by nurse practitioners, at least in states that allow nurse practitioners to provide care without direct physician supervision. Advances in telehealth and home monitoring have further shifted care into patients’ homes, and select patient groups, such as type 1 diabetics, have already assumed much of the routine, day-to-day management of their diseases.

The Role of Community Health Workers

Within this progressive decentralization of care delivery is the possibility of incorporating unlicensed laypeople to assist with care provision. Such peer community health workers would be particularly valuable in addressing healthcare disparities among underrepresented patient populations who are frequently excluded from centralized health services, as they typically share ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and life events with the patients they serve. Their added convenience and accessibility also fill the temporal gaps created by the extensive need for chronic illness, preventive, and wellness care that is often unmet by a hospital-centric model attuned to acute, episodic treatment.

Also known as promotores, community health workers have played an important part in South America’s model of care, and there is anecdotal evidence of successful implementation of community health workers across the United States (AHRQ, 2009). The most common areas of intervention include breast, cervical, and colon cancer screening; childhood and adult vaccinations; HIV, cancer, diabetes, hypertensive, and asthma care; and prenatal care and parenting skills (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2007). Predictably, these implementations of community health workers have almost universally involved information dissemination and targeting of healthcare disparities among underrepresented patient groups.

Impacts of Community Health Worker Programs

A June 2009 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report titled Outcomes of Community Health Worker Interventions found mixed evidence of improved health outcomes and low to moderate evidence of increased appropriate healthcare use. The same report found insufficient data to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of community health worker intervention. The limitations in analysis can be attributed to the small patient populations involved with community health worker programs, the difficulty in performing randomized controlled trials, and the involvement of multiple confounding interventions (Swider, 2002).

Despite the lack of data regarding the financial impact of community health workers, it is reasonable to make some generalizations based on the cost trends that have resulted from similar decentralization of care in other areas, namely the shifting of care to nurse practitioners in the retail clinic model. Direct costs are lower when community health workers are used to replace more expensive providers. However, the amount of savings is modest due to the low level of expertise involved, and hence only the

simplest, and already least costly, work of case managers, social workers, and other ancillary staff is offloaded. The emphasis by community health worker programs on prevention and education will result in a mixture of savings and increased costs, due to increased secondary prevention services balanced by downstream savings from increased primary and tertiary prevention. In addition, community health workers can play a critical role in helping patients reduce consumption of unnecessary services and replace costly preference-sensitive services with less expensive ones.

Like the retail clinic experience, however, community health worker programs can be expected to induce second- and third-order effects that can lead to increased consumption of healthcare services by promoting access to traditional health services. Because of these added systemic effects, community health workers could indeed lead to an overall increase in healthcare spending. This would be consistent with recent analyses of the impact of retail clinics on healthcare costs (Thygeson et al., 2008). However, despite the increased global spending and possible increased per capita spending, it appears that the return on investment of any increased spending on community health workers would almost certainly be higher than that for more traditional healthcare interventions. Furthermore, there are unmeasured benefits related to wellness, including effects on housing, poverty, food, and employment that result from community health worker programs and which have not been incorporated into past cost–benefit analyses.

Barriers to Decentralization in Health Care

Health care has been slow to decentralize its services, despite the gains to be made in affordability and convenience. In the face of overwhelming evidence that the centralized hospital business model has ceased to be viable, supported to a large degree by administered pricing schemes, government aid, and philanthropic support, health care remains recalcitrant. State certifications, licensure, formal training programs, and accreditations are among the many barriers to entry that limit the disruptive decentralization of health care.

A primary defense of these barriers to entry is the concern regarding quality when community health worker programs that use new care providers and settings are introduced. Yet Alcoholics Anonymous, which has been around for 70 years and is a well-studied and respected part of alcohol addiction treatment, fits this model of care. The restriction of community health workers to simple, rules-based care delivery (beginning with simple information dissemination) among populations who would otherwise often not receive any care at all provides a case in which the benefits appear to far outweigh any risks. There must certainly be vigilant regulation to ensure

that quality is not sacrificed, but the vigilance should not be so severe that it comes at the cost of denying care to populations in greatest need.

This perspective must be taken into account as calls for greater regulatory oversight of community health workers gains traction, particularly from professional associations. Impending formal training programs, state certifications, and the possibility of reimbursement will all increase the cost of community health worker programs and may exclude participation of some community health workers and patients, especially among undocumented aliens and non-English speaking individuals.

A possible balanced solution would be to incorporate competency-based licensure, rather than credential-based licensure, of community health workers—and perhaps all healthcare workers.1 Such a system would ensure patients that proficient, high-quality care is always being delivered, while divorcing health care from its more antiquated proxies for ability. Ultimately, everyone should be encouraged to practice up to the limits of their capabilities and licensure, and not so far below them that we continue to price patients out of the healthcare market.

RETAIL CLINICS AND HEALTHCARE COSTS

N. Marcus Thygeson, M.D.

Consumer Health Solutions and HealthPartners

Retail clinics were introduced in 2000 to deliver a limited set of simple clinical services in a convenient, retail setting. They are typically staffed by mid-level providers with remote physician oversight. Additional novel elements of the retail clinic’s strategy include a posted menu of services; walk-in access; minimal support staff and overhead; standardized care processes; and lower than usual, transparent prices.

Retail clinics provide care for a small number of common illnesses, but these conditions comprise a large proportion of traditional primary care practice. The top five retail clinic episodes of care are sinusitis, pharyngitis, otitis media, conjunctivitis, and urinary tract infection (Thygeson et al., 2008). Conditions that can be managed at retail clinic visits account for 13 percent of adult primary care provider visits, 30 percent of pediatrics visits, and 12 percent of emergency department visits (Mehrotra et al., 2008). In an insured population, retail clinic users are healthier than average (Thygeson et al., 2008). Other factors associated with retail clinic use

include younger age, absence of an established provider relationship, and lack of health insurance (Mehrotra et al., 2008).

A Growing Trend

The number of retail clinics in the United States grew rapidly through 2008 and then leveled off at the beginning of 2009 (Merchant Medicine, 2009b). There are now approximately 1,100 retail clinics in the United States with almost 90 percent in urban locations (Rudavsky et al., 2009). Thirty-six percent of the U.S. population lives within a 10-minute drive of a clinic (Rudavsky et al., 2009). The use of retail clinics has also increased. In 2006, one chain (Minute Clinic) was treating 6 percent of retail clinic-eligible episodes in the Twin Cities (Thygeson et al., 2008). In 2008, retail clinics provided approximately 15 percent of retail clinic-eligible care for one large Twin Cities employer. In a national survey of parents with a retail clinic in their community, 17 percent had taken their children to a retail clinic, and 27 percent reported being likely to do so in the future (Davis, 2008).

Addressing Concerns About Retail Clinics

Initial concerns about quality of care at retail clinics have been moderated somewhat by emerging evidence. One study found the quality of care in retail clinics for three common conditions was equal to or better than the quality in physician offices, urgent care centers, and emergency departments (Mehrotra et al., 2009). In Minnesota, the largest operator of retail clinics, Minute Clinic, performs well on Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) acute care quality measures.2 Patients who visit a retail clinic are less likely to have follow-up visits compared to those who visit a physician for the same reason (Rohrer et al., 2008, 2009; Thygeson et al., 2008). Also, an adverse effect on preventive care has not been observed (Mehrotra et al., 2009).

Concerns remain. Will retail clinics increase fragmentation of care for patients with chronic conditions? Will retail clinics lead to convenience-induced demand (patients who would have self-treated if a retail clinic were not available). In a sample of 61 Californians (a mix of insured and uninsured individuals), Wang and colleagues found that 30 percent would have used self-care if a retail clinic had not been available (Wang et al., in press). On the other hand, convenience-induced demand may be uncommon

|

2 |

In 2008, Minute Clinic received a 99 percent score on the HEDIS measure for sore throat care and a 91 percent score on the HEDIS URI measure. Data accessed on July 22, 2009 at http://www.mnhealthscores.org/?p=home. |

in children. In the previously mentioned national survey, only 1 percent of parents reported that they would have used self-care if a retail clinic were not available (Davis, 2008).

Savings Opportunities from Use of Retail Clinics

The care received at retail clinics costs less per episode than care delivered at other sites of service. The average cost per episode for the top five retail clinic episodes is $55 less than in physician offices or urgent care settings, and $279 less than in emergency departments (Thygeson et al., 2008).

To estimate the possible costs savings from retail clinics, we used two approaches. First, if all of the five most common retail clinic-eligible episode types (approximately 250 episodes per 10,000 member-months) were treated in retail clinics, commercially insured population healthcare costs in the Twin Cities might decrease by $1.40 per member per month (PMPM) (0.5 percent of total PMPM, assuming a total PMPM of $300 PMPM). In addition to lower costs per episode, the convenience of retail clinic care might lower costs by leading to earlier treatment, resulting in fewer complications. However, this cost-saving mechanism seems unlikely, given that retail clinics currently treat only minor, acute, often self-limited illnesses.

Another approach to estimating retail clinic cost savings is to apply the per episode retail clinic savings observed in Minnesota to the estimated number of retail clinic-eligible episodes in the United States. These calculations are shown in Table 13-1. Transfer of all retail clinic-eligible visits from physician offices and emergency departments to retail clinics would lead to an estimated savings of $7.5 billion—0.3 percent of the projected

TABLE 13-1 Estimated National Savings—Conversion of All U.S. Retail Clinic-Eligible Visits

$2.5 trillion in 2009 U.S. healthcare spending (CMS, 2009). This represents an upper bound of cost savings.

Savings Estimates: Caveats

However, several factors limit the potential cost savings of retail clinics. First, at least among the insured, patients using retail clinics appear to be switching from physician offices and urgent care centers but not from emergency departments. There was no reduction in the proportion of retail clinic-eligible episodes seen in emergency departments after introduction of retail clinics in the Twin Cities (Thygeson et al., 2008). If we discount emergency department cost savings, estimated potential U.S. savings are $4.2 billion. However, retail clinic use may reduce emergency department visits in underinsured populations (Mehrotra et al., 2008).

Second, over 85 percent of retail clinics are located in the 50 largest U.S. metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) (Merchant Medicine, 2009a). It is not clear that the retail clinic business model will be successful in less urban communities. About 58 percent of the U.S. population lives in the 50 largest MSAs,3 but only 35.8 percent of the U.S. population lives within a 10-minute driving distance from a retail clinic (Rudavsky et al., 2009). Limiting the effect of retail clinics to the 50 largest MSAs reduces the potential savings to $4.3 billion (0.17 percent of total 2009 U.S. healthcare expenditures). With the current retail clinic geographic “footprint,” the potential savings are even smaller ($2.7 billion).

Third, these savings estimates assume there is no convenience-induced demand (patients who would have self-treated if the retail clinics were not available). Convenience-induced retail clinic visits add cost and offset the savings resulting from episodes shifting to retail clinics from more expensive sites of service. As noted above, in one small study, 30 percent of adult patients stated they would have stayed at home if the retail clinic were not available. If 30 percent of retail clinic visits are convenience induced, the estimated maximum possible retail clinic savings in a commercially insured, urban population is reduced to $0.26 PMPM.4 Similarly, 30 per-

cent convenience-induced demand reduces the maximum national potential retail clinic savings to $2 billion (urban communities only).

Finally, these savings estimates ignore the adaptive responses of established healthcare providers. As patients shift to retail clinics, established providers can easily maintain revenue by increasing the number of visits per episode for the remaining patients, and over time by charging more for non-retail clinic-eligible services. Also, established providers are now competing directly with retail clinics for both patients and staff by adopting a convenience care model for the limited set of services provided by retail clinics (Merchant Medicine, 2008; Rudavsky et al., 2009). In the Twin Cities, despite lower retail clinic costs per episode for individuals, population health costs for retail clinic-eligible episodes continued to increase 4.5 percent a year between 2003 and 2006, and the overall commercial cost trend is close to the national average (Thygeson et al., 2008).

Conclusion

Retail clinics are part of a general societal trend toward increasing consumerism and self-service in American health care, but the impact of this trend on healthcare cost and quality is not yet clear. The main benefit of retail clinics appears to be increased, convenient access.

Potential Cost Savings

The potential cost savings from more efficient retail clinic care are limited by a narrow scope of practice and urban location, and is probably not more than $4.3 billion (estimated 0.17 percent of all U.S. healthcare spending). These savings may be totally offset by a combination of convenience-induced demand and the adaptive responses of traditional care delivery systems. The biggest impact of retail clinics in the long run could be the competitive cost structure and pricing changes that they induce, we hope, in existing providers. However, unless the retail clinic model leads to a shift of care from primary care physicians to mid-level practitioners, and from specialists to primary care physicians, it seems unlikely that retail clinics will result in meaningful overall savings.

Facilitating Adoption

The two policy initiatives that facilitated the initial introduction of retail clinics in the Twin Cities included evidence-based clinical guidelines and electronic medical records (EMRs). Integration of well-accepted care guidelines into the retail clinic EMR helped address concerns about quality of care that have been barriers to retail clinic introduction in Massachusetts

and other markets. Expanding the use of care templates in EMRs is likely to support the ability of retail clinics to move “up market.”

Additional policy considerations that affect retail clinics include corporate practice of medicine laws that may be barriers to retail clinic adoption in some states because many retail clinics are owned by nonprofessional corporations. Finally, reforming malpractice laws to provide a higher level of evidentiary protection for guideline-compliant care would likely accelerate adoption of the retail clinic care approach.

Potential Long-Term Impact

For retail clinics to have a sustained beneficial impact on healthcare costs, they need to function like a true “disruptive innovation”5 and expand their services to treat more complex conditions, thereby forcing existing providers to adopt lower operational cost structures for a much broader set of services and patients (Christensen, 2003). This will require substantial redesign of increasingly complex care delivery services. Whether retail clinics will be able to do this is an open question.

CARE COORDINATION AND HOME TELEHEALTH (CCHT)

Adam Darkins,6 M.D., M.P.H.M., F.R.C.S.

Department of Veterans Affairs

In 2007, healthcare expenditure in the United States was 15.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Continuing on this trajectory, U.S. healthcare spending will exceed 31 percent of U.S. GDP by 2035 and reach 46 percent by 2080 (CBO, 2009). Such costs make the U.S. health system, as currently constituted, unsustainable given other competing societal priorities. And the major driver of these costs is care for chronically ill patients; 75 percent of current healthcare resources are expended in caring for people with chronic conditions (Hoffman et al., 1996), such as diabetes mellitus and chronic heart failure. Therefore, any approach aimed at substantively containing U.S. healthcare costs must address the appropriate-

ness, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of managing chronic conditions in the U.S. population.

Despite chronic conditions driving so much of the costs, the U.S. healthcare system is not optimally configured to manage people with these conditions, at either the individual patient level or the population level. These patients typically make unscheduled clinic appointments and frequent emergency room (ER) visits that often result in avoidable hospital admissions. Unscheduled clinic appointments, frequent ER visits, and avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions are major contributors to high healthcare costs (Jencks et al., 2009). Furthermore, the disruption of formal and informal care support systems in the home that takes place with hospital admissions and readmissions in this population of patients can often complicate discharge and precipitate transfer to long-term institutional care with its attendant human and economic costs. Managing these consequences of chronic conditions on the supply side by maintaining unnecessary (or possibly redundant) clinic, ER, and hospital bed capacity further exacerbates healthcare costs. This reaction to the needs of chronically ill patients perpetuates an institutional and provider-centric focus in the healthcare system, which may have been appropriate for managing acute conditions in the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, but it is maladapted to meeting the healthcare needs of patient’s with chronic care needs in the twenty-first century. At this time, managing patients with chronic conditions necessitates more patient-centered approaches that are of proven cost-effectiveness.

A More Patient Centered Approach

Routine outpatient clinic appointments remain the mainstay in managing chronic disease in the United States, but their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have not been substantiated by comparative effectiveness studies. Anecdotally, patients with chronic conditions such as chronic heart failure usually deteriorate at variable times before or after a routine clinic visit. This “just-in-case approach” was the state-of-the-art in the nineteenth century for monitoring patients with chronic conditions with the introduction of new diagnostic devices such as the stethoscope (Laënnec, 1819) and with the advent of therapeutics as we now recognize them (Warner, 1997). However, since the end of the twentieth century, home telehealth devices have been routinely available to continually monitor patients with chronic conditions and transmit vital sign and other disease management data for clinicians to review remotely in the hospital and clinic. In other words, today’s technology provides opportunities to move beyond the just-in-case approach to the just-in-time approach.

Instead of having patients “earn” the right to be seen urgently in a clinic by being in extremis and possibly requiring admission to an intensive care unit, this new technology begs a different question. Would it not make more sense to monitor such patients using home telehealth devices and institute treatment “just in time” when symptoms and signs suggest their condition is deteriorating, thereby obviating further deterioration and its associated risks of mortality and morbidity?

In the late 1990s, a randomized-controlled study of chronic care patients (Johnston et al., 2000) by Kaiser Permanente using video home telehealth systems showed that in 102 patients versus 110 controls the technology was effective, well received by patients, maintained quality care, and had the potential for cost savings. Using this research and their own experience as springboards, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) systematically developed a model of care that combined telehealth methods and technologies with care coordination efforts. Care and case management helped clinicians make the complex judgments needed in managing patients with chronic mental health (Mueser et al., 1998; Ziguras and Stuart, 2000) and general medical conditions (Rundall et al., 2002). The model was formalized within the chronic care model (Bodenheimer et al., 2002): it incorporated patient self-management (Lorig et al., 2001) and an algorithm (Ryan et al., 2003) for the use of home telehealth technologies that included video, monitoring, messaging, and digital image capturing devices. Initially piloted between 2000 and 2003 (Cherry et al., 2003; Kobb et al., 2003), in 2003, the VA scaled the pilot for national implementation as Care Coordination/Home Telehealth (CCHT) (Carmona, 2009; IOM, 2004; McDonald et al., 2007). The VA has defined CCHT as “the use of health informatics, disease management, and telehealth technologies to enhance and extend care and case management to facilitate access to care and improve the health of designated individuals and populations with the specific intent of providing the right care in the right place at the right time” (VA, 2009a).

Care Coordination/Home Telehealth (CCHT) Model of Care

The rationale for developing and implementing CCHT was to meet the chronic care needs of an aging veteran patient population with an anticipated preponderance of those aged 85 years and older (see Table 13-2) and enable them to remain living independently in their own homes, when appropriate. Since its 2003 national implementation, CCHT has been deployed in 150 hospitals throughout the VA Health Care System to manage patients with chronic conditions (both general medical and mental health). The census of patients (number of patients managed concurrently) in the

TABLE 13-2 Examples of Crude Estimates of Cost Reductions That May Be Realizable Through Implementation of Care Coordination/Home Telehealth Outside Department of Veterans Affairs

|

Area of Health Care |

Cost Savings |

Percentage Cost Savings in Population Subset Managed |

Notes |

|

Medicaid non-institutional long-term care expenditure |

$1.7 billion per annum from caring for 20% of population using CCHT |

22% |

2005 figures that assume 20% of estimated $35.2 billion spent on home care-based services (Kaye et al., 2009) can be managed by CCHT at a cost of $1,600 per patient per annum in instead of $13,121. |

|

Hospital readmissions |

$2.2 billion per annum from monitoring patients using CCHT |

48% |

Assumes that hospital admissions (Jencks et al., 2009) could be reduced by 19% and the cost of managing these patients by CCHT is $1.06 billion. |

|

Diabetes care |

$3.9 billion per annum from reducing hospital admissions/readmissions and lengths of stay |

Not calculable for lack of patient denominator to attribute costs to |

Assumes that hospital inpatient stays for diabetes (ADA, 2008) are reduced by 25%. Figure does not include CCHT costs. |

|

Cardiac disease |

$14 billion per annum from reducing hospital admissions/readmissions and lengths of stay |

Not calculable for lack of patient denominator to attribute costs to |

Assumes that the costs of hospital in-patient stays for cardiac disease are reduced by 25%. Figure does not include CCHT costs. |

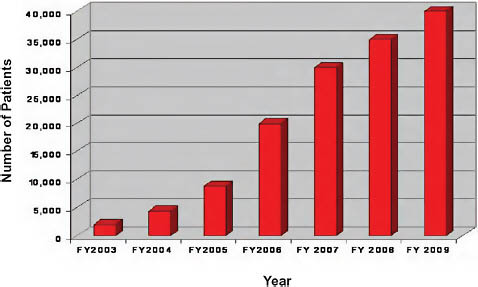

program has increased from 2,000 in 2004 to 39,347 in July 2009 (see Figure 13-1).

Care coordinators, typically registered nurses or social workers, provide the CCHT services. Each care coordinator manages a patient panel of between 90 and 150 patients, depending on the complexity of their conditions, and the care is categorized as noninstitutional care, chronic care management, acute care management, or health promotion and disease prevention. Since January 2004, VHA’s National CCHT Training Center has been certifying these staff using predominantly virtual modalities to provide these services. And the services are not just provided in metropolitan areas; 37 percent of CCHT patients are in rural/remote locations, indicative of the veteran population (7.6 million total enrollees).

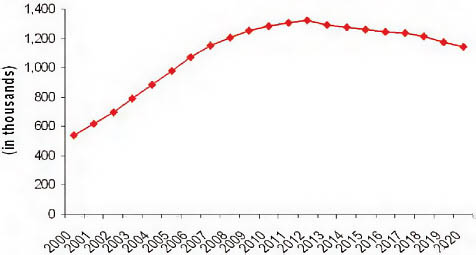

FIGURE 13-1 Number of U.S. veterans in the Veterans Administration aged 85 and older 2001-2020 (projected).

SOURCE: VA, 2005.

CCHT: The Impact

In December 2008, routine management data from the VA’s CCHT program were published as a case report (Darkins et al., 2008) and demonstrated impressive outcomes for a cohort of 17,025 patients, such as:

-

19 percent reduction in hospital admissions,

-

25 percent reduction in lengths of stay,

-

86 percent mean patient satisfaction score, and

-

No measured diminution of health status.

The annual cost of providing CCHT to these patients (whose overall healthcare costs were in excess of $27,000) was $1,600 per patient. Compared to an annual cost of directly providing care in the homes of such patients via nursing teams ($13,121) and to the annual cost of purchasing nursing home care on the commercial market ($77,745), the savings margins are significant on an individual and institutional level. And this intervention is very relevant and has the capacity for expansion; approximately 20 percent of veterans requiring long-term, noninstitutional care are suitable to manage via CCHT (VA, 2009b).

Cost Implications of Implementing CCHT

If taken to the national level, a CCHT implementation in targeted areas could translate to cost savings of between $1.7 and $2.2 billion or

FIGURE 13-2 Department of Veterans Affairs Care Coordination/Home Telehealth Patient census, 2003-2009.

SOURCE: VA, 2009c.

between 22 percent and 48 percent of healthcare costs for the populations of patients so managed (Figure 13-2).

Discussion

In developing and implementing its CCHT program, the VA substantiated the hypothesis that monitoring health-related indices in a population of patients with chronic care needs is a more efficient and cost-effective means of managing veteran patients with complex care needs at risk of needing institutional care. Even though the cost-saving calculations and the possibility of regression to the mean cannot be excluded, the early experiences at the VA are impressive and promising for further national experimentation and expansion.

The VA is an integrated healthcare system that has extensively adopted health information technologies. CCHT is a potentially disruptive technology. Professional, organizational, and reimbursement issues need to be addressed in addition to clinical care considerations.7

REFERENCES

ADA (American Diabetes Association). 2008. Diabetes Care 31(3):596-615.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2008. AHRQ innovations exchange. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=1772 (accessed October 7, 2009).

——. 2009. Outcomes of community health worker interventions. http://www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/comhworktp.htm (accessed October 7, 2009).

Ballester, G. 2005. Community health workers: Essential to improving health in Massachusetts. http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/com_health/com_health_workers/comm_health_workers_narrative.pdf (accessed October 7, 2009).

Bodenheimer, T., E. H. Wagner, and K. Grumbach. 2002. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(15):1909-1914.

Cady, R., S. Finkelstein, and A. Kelly. 2009. A telehealth nursing intervention reduces hospitalizations in children with complex health conditions. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 15(6):317-320.

Carmona, R. H. 2009. Evaluating care coordination among Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of the American Medical Association 301(24):2547-2548; author reply 2548.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2009. The long-term outlook for Medicare, Medicaid, and total health care spending: The long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Cherry, J. C., K. Dryden, R. Kobb, P. Hilsen, and N. Nedd. 2003. Opening a window of opportunity through technology and coordination: A multisite case study. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 9(3):265-271.

Christensen, C. 2003. The innovator’s dilemma. New York: Harper Business. CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2009. National health expenditure projections 2008-2018. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/proj2008.pdf (accessed June 11, 2009).

Darkins, A., P. Ryan, R. Kobb, L. Foster, E. Edmonson, B. Wakefield, and A. E. Lancaster. 2008. Care coordination/home telehealth: The systematic implementation of health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management to support the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 14(10):1118-1126.

Davis, M. 2008. Retail clinics: An emerging source of health care for children. Ann Arbor, MI: C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital.

Handley, M. A., M. Shumway, and D. Schillinger. 2008. Cost-effectiveness of automated telephone self-management support with nurse care management among patients with diabetes. Annals of Family Medicine 6(6):512-518.

Health Resources and Services Administration. 2007. Community Health Worker National Workforce Study: An Annotated Bibliography. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/chwbiblio.htm (accessed August 26, 2009).

Hoffman, C., D. Rice, and H. Y. Sung. 1996. Persons with chronic conditions: Their prevalence and costs. Journal of the American Medical Association 276(18):1473-1479.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2004. 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jencks, S. F., M. V. Williams, and E. A. Coleman. 2009. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New England Journal of Medicine 360(14):1418-1428.

Johnston, B., L. Wheeler, J. Deuser, and K. H. Sousa. 2000. Outcomes of the Kaiser Permanente Tele-Home Health Research Project. Archives of Family Medicine 9(1):40-45.

Kobb, R., N. Hoffman, R. Lodge, and S. Kline. 2003. Enhancing elder chronic care through technology and care coordination: Report from a pilot. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 9(2):189-195.

Laënnec, R. 1819. De l’auscultation médiate ou traité du diagnostic des maladies des poumon et du coeur. Vol. 1. Paris: Brosson & Chaudé.

Lorig, K. R., D. S. Sobel, P. L. Ritter, D. Laurent, and M. Hobbs. 2001. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effective Clinical Practice 4(6):256-262.

Marziali, E. 2009. E-health program for patients with chronic disease. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 15(2):176-181.

McDonald, K., V. Sundaram, D. Bravata, R. Lewis, N. Lin, S. Kraft, M. McKinnon, H. Paguntalan, and D. Owens. 2007. Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Mehrotra, A., M. C. Wang, J. R. Lave, J. L. Adams, and E. A. McGlynn. 2008. Retail clinics, primary care physicians, and emergency departments: A comparison of patients’ visits. Health Affairs (Millwood) 27(5):1272-1282.

Mehrotra, A., H. Liu, J. L. Adams, M. C. Wang, J. R. Lave, N. M. Thygeson, L. I. Solberg, and E. A. McGlynn. 2009. Comparing costs and quality of care at retail clinics with that of other medical settings for 3 common illnesses. Annals of Internal Medicine 151(5):321-328.

Merchant Medicine. 2008. Health systems take on the big shots: 103 clinics now operated under health system brands. http://merchantmedicine.com/News.cfm?view=28 (accessed July 22, 2009).

——. 2009a. Retail clinics by metro area: A geographic look at clinic saturation and demand. http://merchantmedicine.com/News.cfm?view=40 (accessed July 22, 2009).

——. 2009b. Merchant Medicine home page. http://www.merchantmedicine.com/home.cfm (accessed July 22, 2009).

Mueser, K. T., G. R. Bond, R. E. Drake, and S. G. Resnick. 1998. Models of community care for severe mental illness: A review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24(1):37-74.

Rohrer, J. E., K. M. Yapuncich, S. C. Adamson, and K. B. Angstman. 2008. Do retail clinics increase early return visits for pediatric patients? Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 21(5):475-476.

Rohrer, J. E., K. B. Angstman, and J. W. Furst. 2009. Impact of retail walk-in care on early return visits by adult primary care patients: Evaluation via triangulation. Qualitative Management in Health Care 18(1):19-24.

Rudavsky, R., C. E. Pollack, and A. Mehrotra. 2009. The geographic distribution, ownership, prices, and scope of practice at retail clinics. Annals of Internal Medicine 151(5):315-320.

Rundall, T. G., S. M. Shortell, M. C. Wang, L. Casalino, T. Bodenheimer, R. R. Gillies, J. A. Schmittdiel, N. Oswald, and J. C. Robinson. 2002. As good as it gets? Chronic care management in nine leading U.S. physician organizations. British Medical Journal 325(7370):958-961.

Ryan, P., R. Kobb, and P. Hilsen. 2003. Making the right connection: Matching patients to technology. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 9(1):81-88.

Swider, S. M. 2002. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: An integrative literature review. Public Health Nursing 19(1):11-20.

Thygeson, M., K. A. Van Vorst, M. V. Maciosek, and L. Solberg. 2008. Use and costs of care in retail clinics versus traditional care sites. Health Affairs (Millwood) 27(5):1283-1292.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. Ranking tables for metropolitan areas: 1990 and 2000. http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/briefs/phc-t3/index.html (accessed July 22, 2009). VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2005. Washington, DC: VA.

——. 2009a. VHA Directive 2009-002. Patient data capture. Washington, DC: VA.

——. 2009b. Unpublished operational program data 2003-2009. Washington, DC: VA.

——. 2009c. Care coordination services. Washington, DC: VA.

Wang, M. C., G. Ryan, E. A. McGlynn, and M. A. In press. Why do patients seek care at retail clinics and what alternatives did they consider? American Journal of Managed Care.

Warner, J. H. 1997. From specificity to universalism in medical therapeutics: Transformation in the 19th century United States. In Sickness and Health: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health, edited by J. Leavitt and R. Numbers. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Pp. 87-101.

Ziguras, S. J., and G. W. Stuart. 2000. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51(11):1410-1421.