21

Taking Stock: Numbers and Policies

OPPORTUNITIES TO GET TO 10 PERCENT

The final session of the third workshop was devoted to taking stock of the estimates presented in the series, the opportunities to make gains in reducing costs and improving outcomes, and the policy prospects. It was designed to set the stage for specific insights on reaching the target of the series: finding ways to reduce health costs by 10 percent within 10 years without compromising health status, quality of care, or valued innovation.

A LOOK AT THE NUMBERS

J. Michael McGinnis, M.D., M.P.P.

Institute of Medicine

J. Michael McGinnis, in comments in the “look back” session summarizing the issues and estimates from the first two meetings and in the wrap-up concluding session, offered a broad preliminary overview of the implications of just examining totals of various estimates from the workshop presentations and the background literature review developed to inform the discussions. After cautioning that many of the authors’ estimates were themselves still works in progress—with uncorrected gaps, overlaps, and areas of uncertainty—he noted that by taking, as a constrained first approximation, the lower bounds of the estimates from the source material, some interesting observations could be made.

First, at the very highest level, he noted that estimates of excessive expenditures made from four analytically distinct approaches came to roughly similar approximations of the total amount of excess costs for health care in the United States. Specifically, looking at regional variations in Medicare costs, the Dartmouth group estimated overall excess expenditures to be about 30 percent of national health expenditures (Wennberg et al., 2002), or about $750 billion in 2009; the analysis by McKinsey Global Institute suggested that the excess U.S. expenditure relative to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries would be approximately $760 billion (adjusted to 2009 total expenditure levels) (Farrell et al., 2008); the lower-bound totals of estimates of excess expenditures identified in the workshop materials amounted to about $785 billion in 2009; and the estimated possible savings (lower bound, corrected for obvious overlaps) from full implementation of effective strategies in 2009 would be in the range of $550 billion. He also emphasized that such estimates are virtually all unvalidated extrapolations, based on assumptions from limited observations.

Moving to estimates for the next level of granularity—the component domains of excess costs—and again underscoring the various issues, differences, and analytic fragilities, McGinnis used the “lower bound of estimates” approach to summarize in broad terms the aggregate excess expenditures discussed at the workshop, both by the six categories that make up the broad domains of excess and by the component elements discussed for each of the domains. Approximations using this approach would amount in 2009 to about $210 billion in excess health costs from unnecessary services, $130 billion from inefficiently delivered services, $210 billion from excess administrative costs, $105 billion from prices that are too high, $55 billion from missed prevention opportunities, and $75 billion from fraud. These lower-bound domain estimates, and those for the contributing components, are noted in the commissioned background paper that placed the workshop analytics in the context of additional national estimates found in the literature (Box 21-1 below, and see “Summing the Lower Bound Estimates” in Appendix A).

McGinnis also drew on the background paper to highlight and emphasize the methodologic constraints in the analyses and estimates:

-

Varying sources of presentation estimates. The estimates presented throughout the workshop series were calculated by varying methods, including original peer-reviewed research by the presenter and the presenter’s synthesis of the published literature. In the case of the latter, few additional national estimates were found that were not referenced by the presenter.

|

BOX 21-1 Excess Cost Domain Estimates: Lower bound totals from workshop discussions*

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Variations in number of available comparison estimates. The number of national estimates identified within each category varied significantly, with several well-studied categories containing multiple estimates while others contained few or zero comparisons. For estimates in which multiple comparisons existed, some, such as those for tort reform and telehealth, grouped closely with those in the literature, whereas others lay amid a large range of estimates, such as those for tertiary prevention and health information technology.

-

Differences in underlying methodologies. Variation in the estimates within each category often stemmed from differing methodologies, sources of data, study time periods, and scope of work, making direct comparisons between estimates extremely difficult.

-

Need for additional research. Because the number of national estimates identified within each category varied significantly, those categories with few identified national estimates, such as transparency and retail clinics, indicate areas in need of additional research to calculate national impacts and could build on studies of smaller scope noted throughout the report. In addition, in areas with large ranges in estimates, further rigorous research would be beneficial in resolving the differences.

He noted that although many of the workshop calculations were similar to those published elsewhere and summarized in background materials developed for the series, others were quite different—both from each other and from other published material—with respect to variations in methodology and scope of analyses (e.g., federal savings locus compared to societal locus; focus on public and/or private insurance beneficiaries; annual vs. multiyear time frames). For example, Mary Kay Owens’ estimate that a program designed to reduce the incidence of uncoordinated care could result in $271 billion in annual national savings by 2013 exceeded that of Berenson and colleagues (2009), who developed a 10-year estimate of $201 billion in savings from a national effort to improve care coordination targeted at dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

With respect to the returns from investments in preventive services and community-oriented chronic disease management, McGinnis referenced the ongoing field debate about how best to assess those returns (CBO, 2004; DeVol et al., 2007; Russell, 2009; UnitedHealth Group, 2009). He pointed out that most observe that shortfalls in identified dollar savings do not necessarily signify that prevention lacks either cost effectiveness or value.

In turning to a review of the presentations on reducing excess expenditures by broader application of strategies showing early promise in limited studies, McGinnis underscored the difference between the level of unnecessary expenditures and the ability to capture the returns. For

example, it was noted that while an independent estimate from outside the scientific literature calculated the costs of defensive medicine at $210 billion (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2008), Randall R. Bovbjerg’s review of the econometric literature led him to suggest that tort reform would reduce personal health spending by approximately 0.9 percent, or almost $20 billion in 2010. Similarly, several studies highlighted by Rainu Kaushal and Ashish Jha projected significant savings from nationwide implementation of health information technology (HIT), but CBO cautioned that although many policy makers believe that HIT will be a necessary tool in improving the efficiency and quality of health care in the United States, over-optimistic assumptions may temper the magnitude of those estimates (CBO, 2008).

On the other hand, several presentations suggested the potential for considerable savings. Amita Rastogi, for example, offered a savings estimate of $355 billion for the commercially insured from implementation of bundled payments, which is similar to a published estimate of $301 billion in savings from the utilization of bundled payments for acute care episodes (The Commonwealth Fund, 2009). However, it was noted that both require validation with structured studies and experiments. It was also suggested that many potential sources of savings needed more consideration than had been given at the workshops. Additional areas suggested for consideration in terms of both targets and strategies included issues such as fraud and abuse, which have been estimated to cost 3 to 10 percent of total health spending (FBI, 2007) and the implications of the current patent system for the prices of new and emerging technologies.

OPPORTUNITIES TO GET TO 10 PERCENT

Considering the presentations that occurred throughout the workshop series and the literature review presented in the commissioned paper, three thought leaders in healthcare economics—Elizabeth A. McGlynn of RAND, David O. Meltzer of the University of Chicago, and Peter J. Neumann of Tufts University—participated in a panel discussion, offering their views of the most important issues and strategies to engage to reach the goal of reducing health expenditures by 10 percent over 10 years. The following ideas arose from the conversation that offered important insights into the analytics and the broader discussion for lowering healthcare expenditures:

-

Payment reform is clearly one important focus given the clear incentives in the current service-based reimbursement system that distorts the emphasis to volume over outcomes or value.

-

Multimodality should characterize health reform plans because while payment reform appears to be the most likely to yield near-to midterm savings, infrastructure elements such as health in-

-

formation technology and comparative effectiveness research are necessary to facilitate and amplify the effectiveness of payment reforms.

-

Incrementalism—the need for multiple small savings decisions over a single large decision—will be necessary to achieve 10 percent savings. Apart from large savings likely to be possible from streamlining and harmonizing the administrative claims forms and reporting requirements, success from the broad reform approaches required will likely depend on smaller gains in each of the many strategic loci.

-

Analytic advancement of the estimates requires additional accounting for overlaps, cross-integration, and the wave of emerging medical technologies. Simultaneously, estimates extrapolated from “thought experiments” must be interpreted with caution as they may not be as informed from real-life experiences and observations.

-

Value of any particular strategy should not be judged exclusively by the current evidence base as the evidence may be incomplete or imperfect.

Considering the Options

Drawing on her experience studying the Massachusetts healthcare system as a lens for her review of the workshops’ estimates to date, McGlynn described a continuum for considering the reform strategies largely discussed during the second workshop in the series, Strategies That Work. One axis represented the strength of the theory underlying the reform strategy, and the other depicted the level of real-world experience and experimentation with that strategy. With the example of market-based strategies, McGlynn elaborated that this group of reforms has a strong, underlying economic theory, yet they have largely gone untested. A contrasting example focuses on regulatory strategies, which fall on strong supporting economic theory along with significant experience with prior successes and failures. McGlynn indicates that this framework for examining the evidence supporting any single strategy highlights that we may not have enough information to identify a single “silver bullet.” Instead, the panelists all agreed that a multiplicity of reforms will be required to significantly reduce healthcare costs.

Meltzer and Neumann both discussed in detail the cost-saving estimates provided throughout the series and echoed earlier reflections that examining them in the aggregate is both challenging and complex as they reflect a wide range of assumptions and time horizons. McGlynn added that some of the estimates come from experience piloting reform strategies or implementing them in a defined area (albeit at different levels, from municipal to regional

to statewide) yet others come from “thought experiments” that will require real-world testing. The panelists additionally identified that analytics based on pilot tests or single institution experiments must consider the demands required to implement and scale reform nationally. Despite the limitations of the research, all three panelists agreed that large opportunities for minimizing waste and inefficiency exist within the current delivery system.

Reaching the Goal

As the panel considered the reforms needed to meet the goal of a 10 percent reduction in healthcare spending over the next decade, Meltzer defined what this challenge means in real dollars. U.S. healthcare costs are currently about $2.5 trillion and rising about 3 percent in real terms each year. Given the projected cost growth, he explained that within 10 years we should expect healthcare costs to rise to at least $3.2 trillion in today’s dollars. If national expenditures could be reduced by 10 percent, there would be a savings of about $250 billion today and approximately $300 billion in 2020, the equivalent of a cumulative 25 percent reduction in real healthcare spending by 2020 relative to what would have been expected.

While it is important that health status, quality of care, and valued innovation not be sacrificed when attempting to reach these goals, Meltzer encouraged a paradigm shift in light of international health spending comparisons. He suggested that the issue may not be that we spend too much but rather that we get too little. Meltzer explained that, given the nation’s wealth, it would be possible and reasonable for the United States to continue such high and growing levels of healthcare spending if it were obtaining high value from that spending. However, as many participants have asserted throughout the workshop series, the United States is not obtaining that value at the margin.

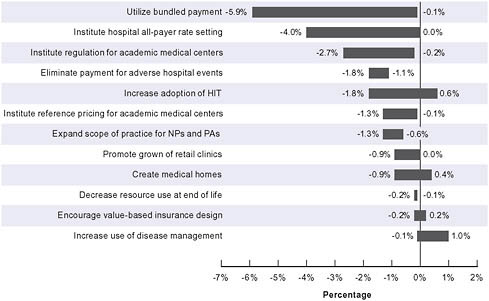

McGlynn offered more specific direction, based on her work in Massachusetts. She first presented the targets and strategies within the framework of basic economic theory. The strategies for healthcare reform essentially addressed the two dimensions of an economy—price and quantity. Target areas for reform under price included excessive administrative costs and excessively high prices. On the quantity side, inefficiently-delivered services, unnecessary services, and missed prevention opportunities represented major targets for reform. As Massachusetts was preparing to embark on the second stage of its healthcare reform agenda, the range of targets and strategies along the price and quantity dimensions were considered. The strategy found to have the most likely significant impact on lowering costs was payment reform, McGlynn explained, as compared to infrastructure improvements and delivery system interventions (Figure 21-1). Both Meltzer and Peter J. Neumann also came to similar conclusions about the importance of payment reform.

FIGURE 21-1 Estimated cumulative savings from selected policy options in Massachusetts, 2010-2020.

NOTES: HIT = health information technology; NP-PA = nurse practitioner and physician’s assistant.

SOURCE: Controlling Health Care Spending in Massachusetts. Online by Eibner et al. Copyright 2009 by RAND Corporation. Reproduced with permission of RAND Corporation in the format Other book via Copyright Clearance Center.

The discussion additionally highlighted that many major examples of bundling success, such as those of Geisinger and Kaiser Permanente, occur within the context of vertical integration of providers. Therefore, the discussants underscored that it remains unclear how bundled payments could be operationalized outside this formal organizational structure. Yet payment reform was thought to be so critical to delivery system reform that the panelists and many other attendees advocated expanding ongoing pilots to test its viability within non-vertical organizational structures.

Neumann explained that payment reform that changes the incentives facing providers (and patients) will likely have the largest effect on cost. Reforms such as bundling arrangements and episode-based payments transform the perverse incentives of the current system from encouraging more services to better services. As lower priorities, Neumann would consider implementation of knowledge-based strategies, preventive care, comparative effectiveness research, and health information technology. Even though they are vitally important to the healthcare reform agenda, he asserted that

adding them to a health system characterized by perverse incentives mutes any positive impact they may have. McGlynn additionally articulated the importance of a rapid learning cycle. Echoing the promise of innovation under a different payment system, she called for structures that allow government and private industry to conceive new ideas, experiment and document evidence, and scale innovation far more quickly than would be possible under a traditional model.

The panelists also discussed the need for incrementalism. Meltzer illustrated this point with the analogy of buying or renovating a home. A 10 percent reduction in costs is rarely the result of a few large decisions but of many small decisions about choice of trim, tile, carpet, hardware, light and plumbing fixtures, etc.—far more small decisions than can ever be characterized by even the most sophisticated imaginative teams of comparative effectiveness researchers or health policy makers. Similarly, Meltzer continued, the myriad of real efficiencies needed to control healthcare costs will be realized only when the payment system is fundamentally reformed and realigned as this policy lever will create the multitude of inducements to facilitate adoption of the necessary infrastructure tools to increase efficiency and quality.

Because the healthcare system is so heterogeneous and precisely because a range of reforms, rather than a single solution, will likely bear the most fruit in cost reduction and growth in quality, the panelists suggested that payment reform may be the most strategic choice. If the payment incentives are realigned and point coherently in the direction of quality improvements at lower cost, the innovations that will emerge from healthcare stakeholders could go beyond what has been imagined in the abstract.

POLICY PRIORITIES AND STRATEGIES

Reflecting on the themes and challenges raised by the discussions and agendas throughout the workshop series, a concluding panel of speakers—Mark B. McClellan from the Brookings Institution, Joseph Onek from the Office of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, and Dean Rosen from Mehlman Vogel Castagnetti—drew from their backgrounds and experiences in federal government in discussing the priorities for effectively advancing healthcare reform policies to lower cost growth and improve outcomes. The far-ranging discussion on the politics of and priorities for currently ongoing health reform discussions centered particularly on four interrelated pillars of the Brookings Institution Bending the Curve report, described by McClellan (Antos et al., 2009):

-

First, better information and more effective tools are needed by all stakeholders, as a foundational element for improving value;

-

Second, provider payments should be redirected toward rewarding improvements in quality and reductions in cost growth, providing support for healthcare delivery reforms that save money while emphasizing disease prevention and better coordination of care;

-

Third, health insurance markets should be reformed and government subsidies restructured to create competition and improve incentives around value improvement rather than risk selection; and

-

Fourth, individual patients should be given greater support for improving their health and lowering overall healthcare costs, including incentives for achieving measurable health goals.

The Benefits of Bundling Reforms

McClellan described the parallels between the workshops and a recent report from the Brookings Institution, Bending the Curve: Effective Steps to Address Long-Term Health Care Spending and Growth. As he explained, that report serves well to provide a sound framework for the discussion of this workshop series by identifying some of the key reforms necessary to have a significant impact on cutting costs and improving quality of health care. McClellan shared a major insight from the work he and his colleagues engaged in: reform must be about taking a varied and differentiated approach to address multiple aspects of the healthcare system at the same time rather than focusing on one area. Because the challenges in the healthcare system are complex, they require a systemic approach in which multiple “pillars,” in turn, can have mutually reinforcing effects. Notably, he explained that the current plans from the President and from the Senate already include critical components of these recommendations.

Onek agreed that there are political advantages as well to bundling reforms in the way McClellan described. His analogy of legislation focused on closing military bases illustrates the point: compartmentalizing reform makes it easier politically to overturn or block reform, but strategically packaging reform initiatives not only makes sense for the reasons McClellan highlighted but also because it allows a broader coalition to support a bill. Just as having Congress determine whether military bases should be closed on an individual basis is doomed because lawmakers will block actions that adversely affect their own districts even if certain base closures are sound from a policy standpoint, so too is a narrow view of reform legislation. He also spoke of the problem created by the false impression that Medicare was being cut in order to finance expansions in coverage for non-seniors. In fact, he stated that Medicare cost savings are required to strengthen that program, regardless of whether we expand coverage overall.

Advancing Current Discussions

McClellan shared that the first pillar of reform identified in Bending the Curve built the necessary foundation for cost containment and value-based care. This foundation depended on significant investment in HIT and on supporting the best use of comparative effectiveness research, building on recent federal legislation. Furthermore, he spoke of the importance of improving the healthcare workforce by incentivizing team-based, integrated approaches to care and the use of HIT as a tool therein. Rosen expanded on that point, raising this area of workforce development, especially in public health, as one that requires a great deal more attention in the national discussion.

The second pillar McClellan discussed is the reform of provider payment systems to create accountability for lower-cost, high-quality care. Rather than focusing on price comparisons between the United States and other countries and price controls as a strategy—which, by itself, he suggested does not change the manner in which health care is delivered—McClellan explained that payment system reform can begin with Medicare and Medicaid by broadening bundled payments, expanding the use of pay for performance, and increasing the payment rates for primary care. Furthermore, supporting additional piloting and replication of innovations such as enhanced episode-based payments will be critical to lasting and meaningful improvements in the U.S. provider payment system. One such innovation identified in the discussion with the potential to improve quality and control costs was accountable care organizations (ACOs), which represent combinations of primary care physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers including specialists, who together would be held accountable for the healthcare costs and quality of care for an identified group of patients. McClellan also underscored the importance of expanding and streamlining the authority of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to rapidly test, evaluate, and expand or eliminate new payment models in Medicare and Medicaid.

Rosen amplified McClellan’s call for expansion of CMS’s authority in piloting and extending innovations beyond its currently “timid” boundaries. He stated that the challenge before the country is an enormous one, and as a consequence, the commitment must be similarly enormous to achieve significant change. While Rosen understood that Congress must be involved in reporting the impact of these pilots, expansion of the 5-year authority for demonstration projects and allowing for the rapid replication of proven innovations such as those found at Geisinger and Intermountain are certainly worth the investment.

McClellan described a third pillar of reform that echoes many of President Obama’s principles for improving health insurance markets. Focusing

on eliminating preexisting condition requirements, introducing risk adjustments, and having reasonable rate bands for patients of different ages, he summarized the core reforms necessary to restructure non-group and small-group markets around an exchange model that promotes competition on cost reduction and quality improvement. Furthermore, he included the promotion of competitive bidding in Medicare Advantage as a strategy to support better health insurance markets. Lastly, improvement of health insurance markets depends on the reduction of inefficient subsidies for employer-provided health insurance. This reform creates an opportunity to redirect those funds to areas in which they can be more cost-effective and far less regressive. Several discussants echoed the emphasis on health insurance market reform, also underscoring the importance of stronger, more streamlined, and more consistent regulation of insurers than is currently possible with a state-based system.

Onek spoke of the thorny problems in redirecting funds or in resource reallocation. Drawing from his experiences in the Carter administration, he emphasized the need to look at spending that is truly excess spending in areas such as Medicaid and Medicare, so that those programs do not become crippled by cuts, spurring unintended consequences in other areas of health care. Additionally, generating savings in both the public and the private markets should be part of every discussion about reducing costs or using existing funds more efficiently.

The fourth and final pillar McClellan discussed supports better individual choices by consumers of the healthcare system. Here, he highlighted that the current proposals before Congress do not speak strongly to these kinds of reforms. Rosen elaborated by sharing his own disappointment that so little attention has been extended to individual responsibility. The role of individual choice and a personal investment in improving one’s own health outcomes are critical points of partnership between consumers and providers, but these issues have been eclipsed by the discussion of other reforms. Here, the panelists stated that reforms could begin with promoting Medicare benefit design that provides better protection to seniors against high out-of-pocket expenses. Introducing a global deductible and a catastrophic out-of-pocket maximum, tiered copayments, and elimination of first-dollar coverage could all be part of this effort. Promoting prevention and wellness that reduced costs was also noted as critical, but McClellan emphasized the need for expanding the evidence base of practical reforms to make progress in this area. Finally, supporting patient preferences for palliative care was another critical area that the Brookings report suggested should be part of broader reform.

McClellan also noted that so much of the discussion in the national debate has been focused on a public insurance plan—and whether and how it should be offered—that other areas of reform, such as liability reform and individual responsibility reforms, have been pushed to the periphery.

While the issue of a public option is important, it has also inhibited discussion of other issues where progress can be made soon and with a greater overall impact. All three presenters also spoke to the issue of medical liability reform, which Rosen identified as an area of untapped opportunity in the national debate. McClellan echoed this sentiment and explained that even though the President raised liability reform briefly in his September speech on health care, there were no details about what shape those reforms might take. Onek highlighted some of the difficulties in this area of reform, because it is not clear, for example, that all defensive medicine is “bad medicine.”

Looking Ahead

Using the framework defined in Bending the Curve, McClellan and colleagues described a national discussion focused on payment reform and, by extension, health insurance reform. However, all agreed that major opportunities for deeper reform, particularly in the area of supporting individual responsibility in health care, remain untapped. Nonetheless, they suggested that some type of reform will occur this year. Keeping an eye on innovations in both the private and the public payer sectors, they suggested that integrating reform initiatives to capitalize on their reinforcing impacts and increasing the capacity for experimentation with new and promising models for care delivery and/or healthcare payment will all be critical in the next chapters of the healthcare system in the United States. They additionally proposed that regardless of what reform legislation passes this year or early next year, we will continue to confront complex issues regarding access, cost, and quality in future efforts and discussions.

REFERENCES

Antos, J., J. M. Bertko, M. E. Chernew, C. Cutler, D. Goldman, M. B. McClellan, E. A. McGlynn, M. V. Pauly, L. D. Schaeffer, and S. M. Shortell. 2009. Bending the Curve. Effective Steps to Address Long-Term Health Care Spending Growth. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Berenson, R., J. Holahan, L. Blumberg, R. Bovbjerg, T. Waidmann, and A. Cook. 2009. How we can pay for health care reform. The Urban Institute.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2004. An analysis of the literature on disease management programs. A letter to the honorable Don Nickles. www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=5909 (accessed 2009).

——. 2008. Evidence on the costs and benefits of health information technology. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/91xx/doc9168/05-20-HealthIT.pdf (accessed September 10, 2009).

The Commonwealth Fund. 2009. The path to a high performance U.S. health care system: A 2020 vision and the policies to pave the way. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/Feb/The-Path-to-a-High-Performance-US-Health-System.aspx (accessed August 26, 2009).

DeVol, R., A. Bedroussain, A. Charuworn, K. Chatterjee, I. K. Kim, and S. Kim. 2007. An unhealthy America: The economic burden of chronic disease charting a new course to save lives and increase productivity and economic growth. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute.

Farrell, D., E. Jensen, B. Kocher, N. Lovegrove, F. Melhem, and L. Mendonca. 2008. Accounting for the cost of U.S. healthcare: A new look at why Americans spend more. Washington, DC: McKinsey Global Institute.

FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation). 2007. Financial crimes report to the public: Fiscal year 2007. http://www.fbi.gov/publications/financial/fcs_report2007/financial_crime_2007.htm#health (accessed September 11, 2009).

PriceWaterhouseCoopers. 2008. The price of excess: Identifying waste in healthcare spending. http://www.pwc.com/us/en/healthcare/publications/the-price-of-excess.html (accessed September 20, 2009).

Russell, L. B. 2009. Preventing chronic disease: An important investment, but don’t count on cost savings. Health Affairs (Millwood) 28(1):42-45.

UnitedHealth Group. 2009. Federal health care cost containment—How in practice can it be done? Working paper No. 1. Minneapolis, MN: UnitedHealth Group.

Wennberg, J. E., E. S. Fisher, and J. S. Skinner. 2002. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Affairs (Millwood) Supp Web Exclusives:W96-W114.