4

Global Public Health Governance and the Revised International Health Regulations

OVERVIEW

As globalization renders national and geographic boundaries increasingly permeable to pathogens, infectious disease control necessitates international cooperation and coordination. This became abundantly clear when severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) emerged in 2003, and it provided a powerful rationale for global public health governance, according to presenter David Heymann of the World Health Organization (WHO). In his contribution to this chapter, Heymann describes the process by which the International Health Regulations (IHR) were revised in the wake of the SARS epidemic and discusses two important challenges that have compromised implementation of IHR 2005: the suspension of polio vaccinations in northern Nigeria and the refusal of Indonesia to share samples of H5N1 influenza viruses collected in that country with the WHO (also discussed in a subsequent essay by Fidler; see below).

“The global public health community has come a long way since the time of the 1918 influenza pandemic,” Heymann observes, as evidenced by the first full application of the IHR 2005 in response to influenza A (H1N1) in 2009. The procedures used by the WHO to declare this event a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC), as stipulated by IHR 2005, are discussed in additional papers in this chapter by Chu et al. and Fidler. Despite this progress, until the issues surrounding the H5N1 virus sharing are resolved, the IHR 2005 “remain a valuable but potential framework within which to address infectious diseases across international borders,” Heymann asserts.

Another challenge to IHR 2005 implementation involves its requirement for significant public health capacity-building, particularly with regard to infectious

disease surveillance. In their contribution to this chapter, speaker May Chu and WHO colleagues Heymann and Guénaël Rodier discuss the obligation of signatories to the IHR 2005 to develop the capacity to detect, assess, and report a possible PHEIC, and they describe steps being taken by the WHO to support progress toward this ambitious and crucial goal by member nations. Chu et al. note that countries may take a variety of routes to build surveillance capacity, including collaboration and networking with other member nations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) not limited to the WHO. They also consider the crucial role of information networks, such as the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), coordinated by the WHO, in broadcasting timely disease alerts to the worldwide health community.

The chapter’s third paper presents a view of the IHR 2005 from the perspective of the developing world. Workshop speaker Oyewale Tomori, of Redeemer’s University in Nigeria, notes that the successful implementation of the IHR 2005 depends on addressing the concerns of policy makers from resource-constrained countries. While some of these concerns are country- and region-specific, he states that “a large proportion of policy-makers in resource-constrained countries perceive that the emphasis of the IHR 2005 on the international spread of disease evinces little concern regarding the burden of infectious diseases on the nations in which they occur.”

Tomori examines significant obstacles to implementing IHR 2005 in Africa, which include multiple barriers to the establishment of surveillance systems; lack of political will and commitment to global public health; barriers to sharing public health information among countries; and constraints imposed by donor agencies on funded projects. He also describes steps that could be taken to correct misperceptions of the IHR 2005 in Africa (and elsewhere) and to enable implementation of these regulations in resource-constrained countries.

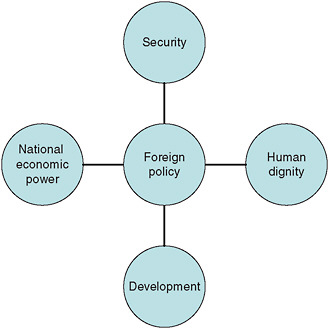

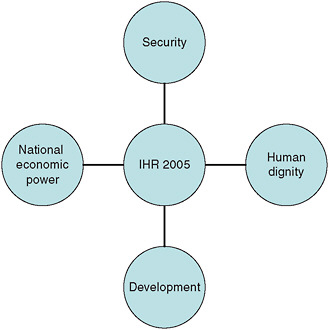

In his workshop presentation, David Fidler of Indiana University stated that the IHR 2005 represents a “radical departure from all previous uses of international law for public health purposes.” After examining the basis for this statement in his contribution to this chapter, Fidler explores a series of challenges that must be overcome if the IHR 2005 are to live up to their promise. His focus is Indonesia’s refusal to share H5N1 viral samples with the WHO’s H5N1 influenza surveillance team and the significance of this controversy to the implementation of IHR 2005 and to global public health governance in general.

In 2006, Indonesia claimed “viral sovereignty” over samples of H5N1 collected within its borders and announced that it would not share them until the WHO and developed countries established an equitable means of sharing the benefits (e.g., vaccine) that could derive from such viruses. Proposals to use IHR 2005 as a means to force Indonesia to share the samples for global surveillance purposes have failed; Fidler notes that this incident highlights the important, yet ambiguous, position of health as a foreign policy issue and its broad implications for global public health governance.

The lack of effective international efforts to address many of the factors that encourage the emergence and spread of infectious diseases (e.g., migration, environmental change, antimicrobial resistance, and armed conflict) increases the potential significance of the IHR 2005 to the future of global health, Fidler argues. He notes that the emergence of influenza A (H1N1) has brought the IHR 2005 renewed political attention and appreciation of its value, and it has demonstrated the WHO’s ability to implement the regulations in a crisis. However, the IHR 2005 must weather far more severe crises than this epidemic to date, Fidler concludes, as well as a host of global trends that threaten to derail advances toward global public health governance.

PUBLIC HEALTH, GLOBAL GOVERNANCE, AND THE REVISED INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS

David Heymann, M.D.1

World Health Organization

Communicating Disease Risk: Then and Now

The 2003 outbreak of SARS was an event of singular importance in demonstrating the need for global public health governance. It began when a physician, who had treated patients with an unknown respiratory disease in the Guangdong Province of China, traveled to Hong Kong on February 21, 2003. From his visit to Hong Kong, the disease that was eventually named SARS began to spread around the world. When the WHO was alerted about the outbreak of an unknown respiratory disease in Hong Kong on March 12, there was only one way to provide 194 ministers of health throughout the world with the information about this threat simultaneously: a press release. It soon became clear that the message had been received: on March 14, the health ministries of Canada and Singapore reported to WHO that persons in their countries who had recently traveled to Hong Kong had a similar disease.

Early Saturday morning, March 15, in Geneva, the WHO duty officer received a call from the Singapore health ministry. A medical doctor who had treated the patients in Singapore had traveled to the United States for a medical conference and was on a return flight to Frankfurt, Germany. WHO was asked to help this medical doctor get medical care in Frankfurt and this was accomplished. At the same time it became evident that the disease was spreading internationally, and, once again, the most effective method of communicating this recent development simultaneously was by press release—one that gave the disease a name, provided a case definition,

and brought it to the attention of international travelers and health workers alike. Clearly this was a less than desirable way to communicate critical information to ministers of health around the world. The fear was that the message would not spread as rapidly as necessary, particularly because it was a weekend.

Five years later, in late October 2008, the revised IHR were in effect. At that time the ministry of health of Sudan reported an outbreak of Rift Valley fever. WHO, along with partners from the Office International des Epizooties2 (OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations3 (FAO), was requested by the government of Sudan to support the ministries of health and agriculture in investigation and containment activities. The risk assessment after the outbreak investigation raised great concern because livestock from Sudan, traded across the Red Sea into Yemen and Saudi Arabia, could have been carrying the Rift Valley fever virus. As these animals were being sacrificed during religious ceremonies, the risk of transmission of Rift Valley fever to humans was high.

Unlike in 2003, at the time of the SARS outbreak, WHO was able to transmit information about the infectious disease threat directly and simultaneously to all 194 ministries of health because of the presence of an IHR4 focal point in each country who is on call 24 hours a day. Health ministers quickly received the information they needed for risk assessment, and they were able to report back to WHO or ask for further clarification electronically and in real time.

Today, the IHR connect national focal points in countries with contact points at WHO regional offices and a universal event management system. The WHO regional offices enter epidemiological and other information necessary for risk analysis and management into this event management system that stores the information and makes it available as needed for risk analysis and management. Feedback to countries through a national IHR focal point completes the reporting link and, if countries require support in outbreak response, a request is transmitted back to the WHO.

|

2 |

The OIE is the intergovernmental organization responsible for improving animal health worldwide. The Office International des Epizooties was created through an international agreement signed on January 25, 1924. In May 2003, the office became the World Organisation for Animal Health but kept its historical acronym OIE. For more information, see http://www.oie.int/eng/OIE/en_about.htm?e1d1 (accessed March 30, 2009). |

|

3 |

Achieving food security for all is at the heart of FAO’s efforts—to make sure people have regular access to enough high-quality food to lead active, healthy lives. FAO’s mandate is to raise levels of nutrition, improve agricultural productivity, better the lives of rural populations, and contribute to the growth of the world economy. For more information, see http://www.fao.org/about/mission-gov/en/ (accessed March 30, 2009). |

|

4 |

The International Health Regulations (2005) represent a legally binding agreement that significantly contributes to international public health security by providing a new framework for the coordination of the management of events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concerns, and will improve the capacity of all countries to detect, assess, notify, and respond to public health threats. For more information, see http://www.who.int/csr/ihr/prepare/en/index.html (accessed March 30, 2009). |

Revising the IHR

The original IHR, established in 1969, were preceded by a long history of public health measures designed to control the spread of infectious diseases across borders (see Gushulak and MacPherson in Chapter 1). These efforts focused on four diseases: plague, cholera, yellow fever, and smallpox. In the case of the IHR (and the accompanying sanitation guidelines for seaports and airports), they attempted to strike a balance between ensuring maximum public health security against the international spread of these four infectious diseases with minimum interference in global commerce and trade.

The original IHR were predicated on the notion that with appropriate measures at border posts it was possible to stop diseases from crossing international borders. Countries in which one of the four reportable diseases (three, after the eradication of smallpox) was occurring were required to notify WHO, and other countries were permitted to take specified measures at airports and seaports to prevent the entry of disease or disease vectors coming from these countries. As an example, when a country reported a yellow fever outbreak to WHO, a report of the infected area was published in the WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record. During the period between reporting and certifying that the outbreak was contained, countries could require yellow fever vaccination certificates from passengers arriving from the affected country.

Recognizing that the world contains multiple and diverse infectious threats beyond these reportable diseases, and that advances in communications could be employed to detect and support the control of diseases that threatened to spread internationally, a decision was made in the mid-1990s to revise IHR. The revision process had two primary goals: to make use of modern communication technologies to understand where diseases were occurring and had the potential to spread, and to change the international norm for reporting infectious disease outbreaks so that countries were not only expected to report outbreaks, but also respected for doing so.

Before 1996, WHO acted only when reports of infectious disease were received from affected countries. As the vision for the revision of the IHR became clear, the WHO began to work more proactively, both in detecting diseases that threatened to cross international borders and in more actively supporting countries in outbreak response should they so request. This vision led to the creation of the Global Public Health Information Network (GPHIN)5 by Health Canada, and the GOARN by the WHO and its technical partners. GPHIN, a web-crawling application,6 searches open sites on the World Wide Web for key words associated with infectious diseases, in multiple languages. It does a preliminary analysis of the

|

5 |

See http://www.who.int/csr/alertresponse/epidemicintelligence/en/. |

|

6 |

A web crawler is a computer program that browses the World Wide Web in a methodical, automated manner. For more information, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_crawler (accessed March 30, 2009). |

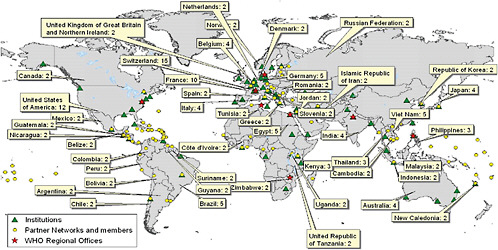

information collected and provides this information every 24 hours to the WHO, where it is verified as rapidly as possible through the WHO system. In 2000, WHO formalized GOARN and it is now able to mount coordinated international response to an infectious disease outbreak by linking its technical partners (institutions, organizations, and networks) with countries that request support.7 Figure 4-1 shows some of the current technical partners of GOARN throughout the world.

GPHIN, and many other global surveillance partners of WHO, were in place when SARS first appeared. While still nameless, SARS was first identified in Asia by GPHIN and several other partners in global surveillance. WHO feared that these reports of an atypical pneumonia with high mortality signaled the beginning of an influenza pandemic because H5N1 was known, since 1997, to be present in that region of China. Within a period of a weeks after the first recognized case, GOARN mobilized more than 115 experts from 26 institutions and 17 countries to support infected countries in outbreak investigation, patient management, and outbreak containment. These experts, and others, exchanged epidemiological, laboratory, and clinical information about the outbreak in real time. WHO used this information to make recommendations on patient management and eventually issued travel recommendations in an attempt to curb, and eventually stop, the international spread of this newly recognized virus.

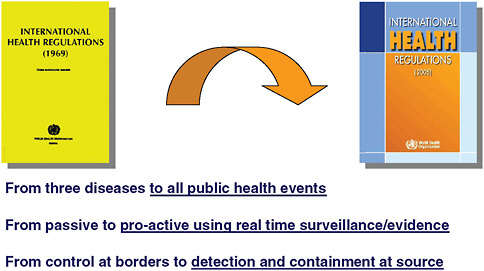

The SARS outbreak was a turning point in international collaboration on infectious disease control, and many ministers of health became convinced that they must change the way they work together to fit this model. At the World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2003, a resolution was passed by WHO member states that confirmed that WHO could receive and use infectious disease information from sources other than countries for risk assessment with the affected country in a confidential manner, and it also mandated reporting of a wider range of infectious diseases with potential for international spread rather than just yellow fever, cholera, and plague. This resolution helped increase the pace of the revision of the IHR and, in 2005, the revision process was completed with full endorsement by the WHA. The revised IHR enable more proactive surveillance for an event that could be considered a PHEIC, whether it be infectious, chemical, radiological, or food-related. With a core capacity strengthening requirement for countries in epidemiology and public health laboratory, the revised IHR will strengthen the ability of countries to detect and contain outbreaks at their source so that they do not have the opportunity to spread internationally. Figure 4-2 compares the major distinctions between the 1969 IHR and the 2005 revision.

Specifically, the revised IHR mandate:

-

Strengthened national core capacity for surveillance and control, including at border posts;

FIGURE 4-2 Major distinctions between the IHR 1969 and the revised IHR 2005.

SOURCE: Heymann (2008).

-

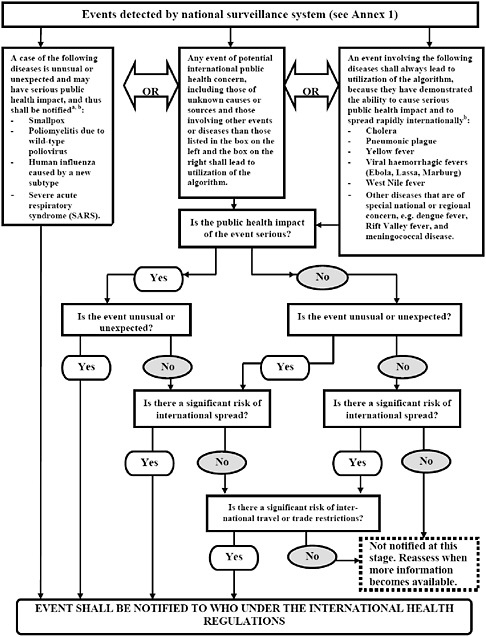

Reporting of possible PHEICs (see Figure 4-3), and of four specific diseases even if only one case is identified: SARS, smallpox, avian influenza, and polio;

-

Collective, proactive global collaboration for risk assessment and risk management; and

-

Monitoring of implementation by the WHA.

Global Governance and the Revised IHR

Polio Eradication

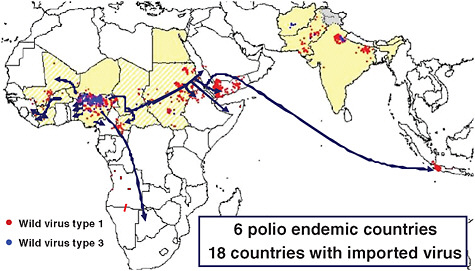

In 1988, polio was present in more than 125 countries, where it caused paralysis in approximately 1,000 children each day; and access to polio vaccine was inequitable between countries. Polio vaccine rapidly became available after 1988 in sufficient quantities for all countries and, by 2003, polio remained in only six countries: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, Niger, and Nigeria. Fewer than 1,000 children became paralyzed in the course of that entire year, and there was equitable access to vaccine. But during the latter part of 2003, rumors began circulating that polio vaccines were causing sterility in young girls.

These rumors led to a suspension of polio vaccination in 2003 in northern Nigeria. The result was that the polio virus began to migrate with people from northern Nigeria as they crossed Islamic pilgrimage routes and Muslim trade routes throughout Africa. Polio virus from Nigeria traveled as far as Saudi

FIGURE 4-3 Requirements of the IHR 2005.

SOURCE: Heymann (2008).

Arabia, Yemen, and Indonesia, and polio returned to countries that had previously become polio free. In the first year after vaccinations ceased in northern Nigeria, it cost the Global Partnership on Polio Eradication an estimated $500 million to stop polio in reinfected African countries, as illustrated in Figure 4-4.

Initial efforts to deal with this situation involved demonstrating that polio vaccines contained no impurities or hormones that could cause sterility in young girls. Vaccines were sent by the Nigerian government to WHO Collaborating Centers on polio in South Africa and India, and testing was overseen by experts from Nigeria. At the same time, an offer was made by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) of polio vaccine manufactured in an Islamic country.

WHO representatives, along with Ministry of Health officials, engaged in personal discussions with the governors of the northern Nigerian states who had ordered that polio vaccination be stopped. The governors convened groups of pediatricians to help them determine whether the risk was greater from vaccine or from polio, at a time when approximately 82 percent of all polio in the world was occurring in northern Nigeria. These concerns were also taken to the Organization of Islamic Conferences (OIC), whose members understood the importance of this issue in their own countries. The OIC heads of state discussed the importance of polio eradication in a plenary session at their summit in 2003 in Malaysia, and then passed a resolution to support polio eradication that has been reviewed each year since then at annual OIC minister of health meetings.

Neither proof of vaccine safety nor political and religious advocacy were, however, enough to convince northern Nigeria to resume polio vaccination. The issue was then taken to the broader Islamic community that produced a series of religious

FIGURE 4-4 The international spread of polio from Nigeria, 2003-2005.

SOURCE: Reprinted from WHO (2005) with permission from the World Health Organization.

fatwas (declarations) and academic statements regarding the safety and importance of polio vaccination. One religious leader in particular, the late Imam Cheik Cisse of Senegal, was very active in northern Nigeria, traveling there to advocate for the importance of polio vaccination, vaccinating children himself as an example.

As an additional measure, WHO convened an ad hoc expert advisory group on polio epidemiology and public health to determine if there were any evidence-based measures that could be recommended to stop the international spread of polio. This group concluded that evidence in the scientific literature supported the fact that polio-immune adults could carry the virus in their intestines for periods up to a month, that the polio virus therefore had the potential to be carried wherever persons from polio-infected areas traveled, and that a booster dose of oral polio vaccine could decrease the period the virus was carried. A recommendation was made that a booster dose of oral polio vaccine be provided for persons traveling from countries with polio. Saudi Arabia, where there had been imported polio from Nigeria, followed these recommendations and began requiring booster vaccination of Islamic pilgrims before they left their country if it was polio-infected, and also upon the arrival of the pilgrims in Saudi Arabia. These recommendations continue to stand and are being considered as standing recommendations under the IHR, where polio is one of those four diseases named that even one case requires reporting.

Finally, resolutions were passed in the WHA regarding measures to be taken when polio spread internationally, and the most recent, in 2008, was widely reported

in the Nigerian press, leading in part to further engagement of Nigerian President Umaru Yar’Adua, who stated publicly that “[w]e will do everything humanly possible to ensure that polio is finally and totally eradicated from Nigeria.”

Nevertheless, the polio virus continues to circulate in northern Nigeria. As of April 2009, 184 Nigerian children have been paralyzed from polio this year (WHO, 2009a). The polio virus also continues to spread to neighboring countries, and every aspect of global governance, including work within the framework of the IHR, continues to be used to stop its international spread. While polio vaccination has resumed in northern Nigeria, efforts have not yet been effective enough in reaching children to provide the level of herd immunity necessary to interrupt transmission.

Once countries succeed in interrupting the transmission of polio worldwide, other risks to polio eradication will remain. The Sabin vaccine virus is able to revert to a wild form either through genetic recombination or reassortment. After eradication has been certified, a WHO group of advisers has concluded that it will therefore be necessary to stop the use of oral polio vaccine to minimize this risk, and countries continuing to vaccinate would have inactivated polio vaccine as an alternative. It remains to be seen whether the IHR will be used by member states in any way at the time of oral polio vaccine cessation to ensure that all countries stop its use simultaneously so that no country places others at risk. It likewise remains to be seen if the IHR will be used to address another post-eradication risk, destruction, or consolidation under high security of those polio viruses that remain stored in research and diagnostic laboratories.

Thus, while the IHR provide a useful framework that enables international coordination for the prevention and control of infectious diseases, their use is not automatic. It depends rather on the collective will of WHO member states to use them as a framework to resolve public health issues, on a case-by-case basis.

Influenza Pandemic Preparedness

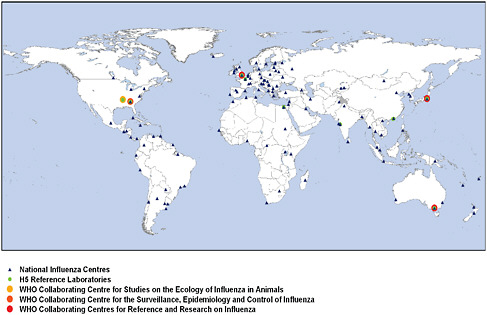

WHO facilitates the work of a network of 127 national influenza centers throughout the world that regularly provide seasonal influenza viruses to one of four WHO Collaborating Centers on influenza where genetic characterization is conducted (Figure 4-5). Results of sequencing are then used for a comparative risk analysis, and an annual recommendation is made for the composition of seasonal influenza vaccine.

Once the recommendation is made as to which virus strains should comprise the next seasonal vaccine, it takes up to six months to prepare the vaccine for use. The global capacity for seasonal influenza vaccine production varies between 350 million and 500 million doses, far less than would be required to produce an influenza vaccine for a pandemic.

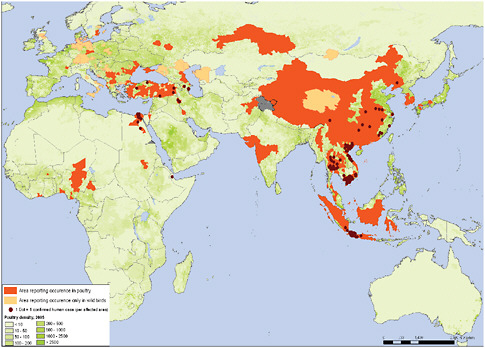

The same network of laboratories also tracks potential pandemic influenza viruses. Figure 4-6 shows the geographic locations of human zoonotic infections

FIGURE 4-5 WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network (GISN), July 2008.

SOURCE: Heymann (2008).

with novel avian influenza (H5N1) viruses, in countries where H5N1 influenza is occurring in poultry.

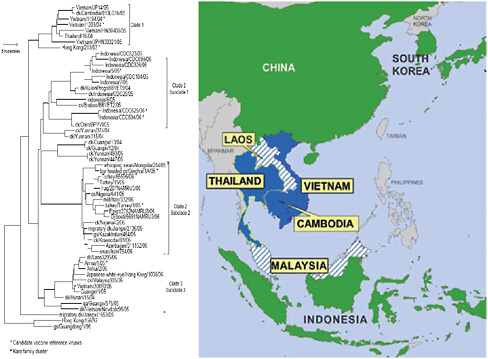

Figure 4-7 presents an analysis of genetic information from the H5N1 virus collected by the Global Influenza Surveillance Network and clearly demonstrates the instability of the virus. It remains to be seen whether the H5N1 virus will undergo an adaptive mutation, such as was thought to have occurred to produce the 1918 (H1N1 influenza A) pandemic virus, or whether genetic reassortment among influenza viruses will produce a pandemic strain as occurred in other twentieth-century influenza pandemics. If either scenario should unfold, WHO will spearhead the global pandemic response as it has done for H1N1 influenza beginning in April 2009.

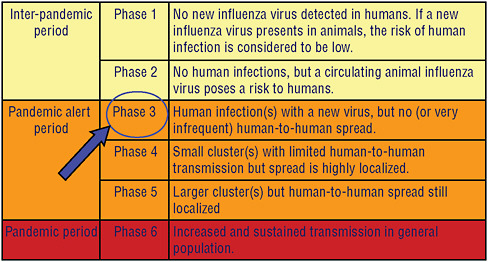

Figure 4-8 illustrates the current pandemic alert phase of the H5N1 virus. If phase 3 for H5N1, its current level of alert, proceeds to phase 4 with localized human-to-human transmission, and if this change in phase is detected at an early stage, WHO and its partners will work with the county or countries involved to attempt to rapidly ring fence such an outbreak with vaccine and antiviral drugs in hopes of slowing virus spread, or stopping its spread altogether. The capacity for such a rapid response is currently being established in countries and in regions where pandemic influenza is considered most likely to originate, and the emergence H1N1 of 2009 has given countries the opportunity to test their rapid

FIGURE 4-6 Confirmed human and poultry infections since 2003.

SOURCE: Data based on OIE and national governments reporting. Map produced by Public Health Mapping and GIS, Communicable Diseases, WHO. Reprinted with permission from the World Health Organization.

response capacity as the pandemic alert was raised to phase 5 and finally 6 during the first half of 2009. The pandemic scale in Figure 4-8 has been modified to further characterize phase 6 by community level outbreaks in at least one other country and in a different WHO region from that country or those countries where phase 5 has initially been declared.

On June 11, 2009, the WHO raised the pandemic alert level of the influenza A (H1N1) from 5 to 6. Phase 6, the pandemic phase, is characterized by community level outbreaks in at least one other country in a different WHO region in addition to the criteria defined in Phase 5. Designation of this phase indicates that a global pandemic is under way (WHO, 2009b).

In anticipation of a decision to implement a containment strategy, WHO maintains stockpiles of antiviral drugs, as do the U.S. government and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), for use by any country in the event of a change in the alert phase. As soon as an H5N1 vaccine is licensed, WHO will also stockpile vaccine. The virus composition for H5N1 vaccine is recommended by the same risk assessment process as that used for seasonal vaccine composition, through the Global Influenza Surveillance Network.

In 2007, the Indonesian minister of health raised an important issue concerning preparations for pandemic influenza. She observed that while Indonesia and other developing countries had freely shared influenza viruses obtained within their borders through the Global Influenza Surveillance Network, these countries would be less likely to have vaccine in the event of a pandemic because of issues related to cost and production capacity.

In order to better understand the issues, WHO conducted a meeting of experts, hosted by the government of Indonesia, to understand how countries might more equitably share in the benefits associated with virus sharing. This expert group identified the following issues that needed resolution to ensure more equitable sharing of benefits:

-

Greater participation by developing countries in the Global Influenza Surveillance Network, through the strengthening and certification of additional national influenza centers and WHO Collaborating Centers in developing countries;

-

Greater transparency by WHO in the handling of influenza viruses; and

-

Greater access to pandemic vaccines for all countries, with an increase in developing country vaccine production capacity.

To date, some countries have chosen not to continue to send H5N1 influenza viruses for risk analysis to the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network, making risk analysis less complete than previously when all H5N1 viruses were freely shared. As is the case for polio, avian influenza is one of the four named diseases that require reporting under the IHR. Rather than invoke the IHR to address this issue, however, WHO member states have preferred to address the issue of H5N1 virus sharing and sharing of the benefits through a resolution at the WHA in 2007. This resolution has called for a series of intergovernmental meetings currently under way to discuss, debate, and develop a new framework for the sharing of influenza viruses and sharing in the benefits. In addition, WHO is undertaking a number of extra measures, including (1) establishment of a more transparent virus traceability mechanism that permits countries to determine how the viruses they provide to the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network are being shared; (2) implementation of a global pandemic influenza vaccine plan that includes vaccine manufacturing technology transfer to developing country vaccine industry; (3) increasing the number of developing country laboratories participating in the Global Influenza Surveillance Network; (4) assessing various financial mechanisms that could be used to purchase pandemic vaccines; and (5) establishing an H5N1 vaccine stockpile for use in rapid response to a phase 4 or phase 5 alert, and provision of vaccine to countries early in a pandemic should it be caused by H5N1.

The global public health community has come a long way since the time of the 1918 influenza pandemic. By revising the IHR in 2005, there is now a frame-

work within which all countries can collaborate in risk assessment and management in order to limit the impact of the next influenza pandemic. They have now been tested for influenza H1N1 in April 2009 when an emergency committee was convened to assess the risk from H1N1, but so far the IHR have not been selected as the mechanism under which to work in resolving the very important issues related to sharing the H5N1 virus and sharing of the benefits. It remains to be seen when and how the intergovernmental process currently under way will resolve the issues of H5N1 virus sharing and sharing of the benefits through the process established under the WHO Resolution.

Conclusion

There are many different mechanisms of global governance. They include conventions such as the framework tobacco convention established several years ago through WHO; regulations, such as the IHR; resolutions which express collective political will, such as that for H5N1 virus sharing and sharing of the benefits; norms and standards to which countries are expected to adhere; and finally, some forms of advocacy. Countries together interpret which of these mechanisms to invoke, and global governance is therefore determined collectively as a situation unfolds. In the case of the IHR, they remain a valuable but potential framework within which to address infectious diseases across international borders.

CAPACITY-BUILDING UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS TO ADDRESS PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCIES OF INTERNATIONAL CONCERN

May C. Chu, Ph.D.8

World Health Organization

Guénaël Rodier, M.D.

World Health Organization

David L. Heymann, M.D.

World Health Organization

Overview of the Historical and Revision of the International Health Regulations: the New Paradigm

When the WHO was chartered in 1949, one of its earliest tasks was to create “The International Sanitary Regulations” (1951), which sought to harmonize and replace 13 or more international agreements concerning quarantine and sanitary

measures (Hardiman, 2003). In subsequent years, these regulations were added to, revised, and then renamed the International Health Regulations (IHR) in 1969. By 1995, the governing body of WHO, the World Health Assembly (WHA), made up delegates of all the member states, adopted the resolution to modernize the 1969 IHR to take into consideration the evolving stage of global public health threats. Their vision was for the revised IHR to be able to accommodate a world that would be alert and be able to detect and respond to international infectious disease threats and public health events within 24 hours of its first report using the most up-to-date means of global communication and collaboration. The revision would aim to facilitate a change in the norms surrounding reporting, making it expected and respected to report infectious disease outbreaks—particularly public health events (both infectious and noninfectious) that may impact international trade and travel.

The revision was needed to bring the IHR into the modern age and take into account the changes in global climatic and social environments. In the IHR 1969, reporting of disease occurrence was limited to a few diseases (plague, yellow fever, cholera, and smallpox). After eradication, smallpox was removed leaving the three diseases as the only ones reportable to WHO by the affected member state. This rigid approach meant that emerging or reemerging diseases—public health threats that can be rapidly transmitted and transported across the world, such as SARS and pandemic influenza—would not have been notifiable. The IHR (1969) not only limited how such occurrences could be officially reported, they also did not link to potential responses thus leaving a gap in assessing what the risks might be if there was international spread. There was reluctance to report by the affected country because of concerns over halting trade and keeping travelers away; at the same time, other countries did not have equal and open access to the available information The absence of incentives to report and the absence of risk communication and reasonable control measures often led to over-reaction by the global community, heightened the sense of vulnerability, and even exaggerated fear and engendered mistrust. Thus, the key to reestablishing trust and confidence was to demonstrate to all member states that a set of revised procedures would be in the best interest of all countries, whether the member state is experiencing a public health event or seeking to protect themselves from becoming affected (Fidler and Gostin, 2006). Furthermore, capacity strengthening and transparency to share information should be the responsibility of a country to contain the risk and not spread it further to other member states territories. Countries cannot do it alone; therefore, a collaborative environment must be created so that countries can share their experiences and receive benefits for being alert and responsive.

The 58th WHA unanimously adopted resolution WHA58.2, the revised IHR, in 2005. A total of 194 signatory state parties (193 member states plus the Holy See) have committed to this responsibility. Article 2 of the IHR (2005) states that the primary purpose of the IHR (2005) is to “prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease commen-

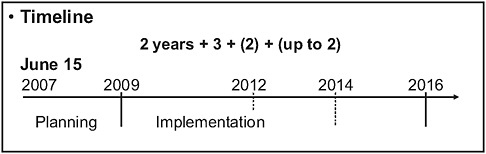

surate with public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” (WHO, 2005). The articles reflect a paradigm shift: (1) from reporting three diseases to reporting all public health events that may likely spread internationally and affect travel and trade, (2) from passive reporting and pre-set measures to proactive surveillance and tailed response, using real-time evidence for risk assessment and risk management, and (3) from control at borders to detection and containment at the source of the event. Information from public health events still requires the country to officially report to WHO, although its sources may be gathered from multiple streams of information. WHA58.2 would come into force on June 15, 2007, with a period until 2012 for preparing, review, and planning for each signatory member state (State Party) to meet the requirements of the IHR (2005).

IHR: States Parties Must Invest in Capacity-Building

The revised IHR (2005) set a new paradigm and opportunity for WHO member states to share health-related risk information affecting travel and trade in a more transparent and organized manner.

Compliance with IHR (2005) requires each State Party to develop, strengthen, and maintain, as soon as possible but no later than 5 years from the entry into force of the regulations (Figure 4-9), the core capacity to detect, assess, notify, and report events. Each of the 194 state parties assumed the responsibility to develop the capacity to respond promptly and effectively to PHEICs as set out in the articles and Annex 1A. Each State Party is asked to utilize existing national structures and resources to meet their core capacity requirements in a national tiered system and the system is operational around the clock. A National Focal

FIGURE 4-9 Timeline for implementation of the IHR to strengthen national capacity (194 States Partiesa).

aWHO has 193 State Parties. The additional State Party is the Holy See who is not a WHO member state but has joined IHR on a voluntary basis.

SOURCE: Chu (2008).

Point (NFP) is named by the State Party to serve as the communication conduit with WHO.

In terms of capacities, states parties are required to develop and strengthen core public health capacities for surveillance and response throughout their territories (as well as capacities at some points of entry). As part of these requirements, the IHR (2005) mandate that domestically all “essential information” be communicated from the local to intermediate levels concerning reportable events, including available “laboratory results.” At the national level, all states parties must have the domestic capacities to provide support through specialized staff, laboratory analysis of samples (domestically or through collaborating centers), and logistical assistance (e.g., equipment, supplies, and transport), as well as have links for dissemination of information. Countries must also facilitate the transport, entry, exit, processing, and disposal of biological substances and diagnostic specimens, reagents, and other diagnostic materials for verification and public health response purposes.

Annex 2 is a decision instrument tool for the assessment and notification of events that may constitute a PHEIC (Figure 4-10). This decision instrument replaces the list of the three reportable diseases and is designed to aid countries in identifying an event that may spread internationally. There are three situations to be considered: (1) a single occurrence that requires reporting (i.e., a single case of SARS, smallpox, pandemic influenza, and all diseases of high transmissibility with potential to become serious public health threat); (2) any known disease whose source is found in its natural endemic foci but, if spread or appearing outside of its natural environment, could lead to a PHEIC, such as, for example, the plague from New Mexico focus, in the United States, appearing out of context in New York City would require investigation and risk assessment; and (3) any public health event of serious impact in a community with potential to spread beyond its source (i.e., food product contamination) for which answers to the four key questions posed in Annex 2 will determine if the event may constitute a PHEIC, and consequently, be notified to WHO under the IHR (2005). For instance a public health event with potential of international spread should be reported if replies to at least two of the questions are “yes.” Upon notification of the event, WHO has the mandate to collect and analyze information regarding the events and to determine its potential to cause disruption in travel and trade, irrespective of the origin or source, and may share such information with countries and intergovernmental organizations following verification with the affected State Party.

There is provision in the IHR (2005), particulary under Article 44, for State Parties to develop collaborations with each other for detection, assessment, facilitation of technical cooperation, and logistical support; share mobilization of financial resources; and to formulate legal instruments for implementation of the IHR (2005). WHO is asked to collaborate with state parties, upon request, to develop, strengthen, and maintain these capacities. Furthermore, collaboration may be implemented through multiple channels, using networks, the

FIGURE 4-10 Decision instrument for the assessment and notification of events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern.

aAs per WHO case definitions.

bThe disease list shall be used only for the purposes of these Regulations.

SOURCE: Reprinted from WHO (2008) with permission from the World Health Organization.

WHO regional offices, and bilateral partnerships, and through intergovernmental organizations and international bodies.

Each State Party shall assess events occurring within its territory by using the decision instrument in Annex 2. Each State Party shall notify WHO, by the most efficient means of communication available, by way of the National IHR Focal Point, and within 24 hours of assessment of public health information, of all events that may constitute a PHEIC within its territory in accordance with the decision instrument, as well as any health measure implemented in response to those events.

Following a notification, a State Party shall continue to communicate to WHO timely, accurate, and sufficiently detailed public health information available to it on the notified event, including, where possible, case definitions, laboratory results, source and type of risk, number of cases and deaths, conditions affecting the spread of the disease and the health measures employed, and report, when necessary, the difficulties faced and support needed in responding to the PHEIC (WHO, 2005).

WHO may request from the affected or reporting country, in response to a specific potential public health risk, relevant data concerning sources of infection or contamination (including vectors and reservoirs) at its point of entry that could result in international disease spread.

The Challenges: Normative Versus Reality

The responsibilities assumed by the state parties require resources, commitment, and spirit of collaboration. Countries should not be expected to deliver this on their own, nor should they do so without some harmonization of approaches and access to tools to allow them to communicate rapidly and efficiently.

At the core of creating a transparent and informative work space, the WHO has built upon its Event Management System (EMS), which consolidates through its WHO portal daily inputs from a variety of information sources: formal and informal; individual, governmental, intergovernmental and regional; and collected from specifically designed tools that enhance early warning signals of events of high concern. It is the role of the EMS to serve as a clearinghouse, to screen, assess, verify, and report to member states as to the risks and to determine collaboratively the management of the risks. It is through this clearinghouse that the IHR NFP may use the Events Information Site (EIS) to inform, access, and share information with the WHO and to inform their own competent authorities of actions and events. The EIS establishes protected access for IHR-related information, connecting the WHO and the NFP in a privileged but transparent manner that is operational 24 hours every day. New events are posted and shared as soon as they are notified, with risk-assessment comments. Some may argue this approach limits the sharing of information, bypassing previously more spontaneous ad hoc reporting and wider access by those interested in sharing outbreak news; others

feel more at ease with the pass-coded site because more descriptive details are shared freely. Information is shared through the Disease Outbreak News,9 the Weekly Epidemiological Record,10 and with partners through GOARN.11

Response to and management of public health events is a more established process through the collective experience and synthesis of “lessons learned” from outbreak response. The Alert and Response Operations (ARO), GOARN, and other outbreak response efforts of a number of dedicated teams in WHO has led to the development of a payload concept of operations to support functions. The concept envisions a pre-set, prepared system into which one drops the specific event (be it of chemical, radionuclear, food safety, or epidemic origin), this coordinated approach allows for better communication and field operations support that is constantly under information analysis, verification, and risk assessment while tapping into the expertise of partners through GOARN, regional and national experts, and specific collaborative networks (Kimball et al., 2008; Koplan et al., 2005).

The challenges to building capacity are inherent in the divergence of the systems among the state parties. Essentially, there are 194 flavors because every State Party has built its own system. However, they have the same goals; therefore, each “pathway” will have to be constructed to (1) utilize and build on existing infrastructure, strengthening them as needed, and enjoin partnerships where one country can assist another; (2) build trust and confidence in the data received and provided, thus committing to a quality assurance framework that complies with international standards; (3) incorporate the vertically invested programs for disease control and surveillance, making state parties aware of the IHR requirements and discussing with them the potential leveraging of resources; and (4) support countries to carry out cross-sectoral assessments, planning and implementing their capacity-building process by provision of consultations, tools, and shared costs. Questions unique to each country relate to whether the countries support a centralized (public health clinics to district, to central) or federated systems (multiple supra-national, or regional centers)? Whether there is regulation in place for sample collection and their transport? What would be the minimal level of quality assurance? What types of data should be collected for reporting public health events? Who will be responsible to ensure a functional system and how would it be paid for?

WHO’s Experience in Implementing the Revised IHR

Since the entry into force of the IHR (2005) on June 15, 2007, the WHO regional offices (AFRO, AMRO, EMRO, EURO, SEARO, and WPRO) have

worked tirelessly to assess their member states’ national and regional capacities and to assist them in making their IHR plans for building core capacities. The next steps are to implement the plans using a coordinated and cross-sectoral approach. There is no one solution that fits all the models, and countries differ in their steps to reach the goals; countries also have to request assistance from WHO partners and work through networks to build their capacities.

As of the end of 2008, the IHR NFP roster has been completed. Each country designated an institution to serve as the NFP and named up to three persons who would rotate the responsibility to provide all-time, all-on support. Each State Party has been requested to nominate an expert who may be called upon to serve on the Emergency Committee should a PHEIC be declared, and such expert advisory group needs to be assembled to give advice to the WHO Director-General.

A number of partners and countries have offered to provide resources and expertise to support the implementation of IHR for other state parties. Several key projects in countries are under way to help implement a country’s plan through demonstration projects, collaborative network support, national institutes support, global security initiatives, and regional alliances. Some projects are focused on ensuring that countries review and define their legislative support, others are focused on training, and others are focused on awareness workshops, investment in infrastructure, and setting of international norms and standards. Specific disease programs such as polio eradication, influenza, and HIV have also given countries resources and capabilities and have allowed for surge capacity planning. These investments have been critical elements in getting the cross-sectoral buy-in to prepare for the IHR.

As an example, countries have been involved in their own pandemic planning for several years, which has been especially heightened since the emergence of the A (H5N1) avian influenza virus. Though this targeted a specific disease, the preparedness process is very much appreciated by the national planners as they develop plans for IHR implementation. Some countries have had to experience avian influenza outbreaks in real time while others have prepared through drills and exercises. Nevertheless, the overall awareness and confidence in moving forward on IHR implementation has greatly benefited from the experience.

A Recent Update

An update to the Institute of Medicine workshop in December 2008 that fully illustrates the implementation of the IHR (2005) is the emergence of the pandemic A (H1N1) 2009 virus (WHO, 2009). Following the written IHR, an Emergency Committee was convened to review the evidence according to Annex 2 and, based on available evidence, the WHO declared a PHEIC on April 25, 2009. The virus was first detected in the United States in early April and first reported, in retrospect, in Mexico. Specimens were shared with its neighboring alliance countries (Canada and the United States; CDC, 2009), both of whom confirmed

the emergence of the new virus and made reports through their NFP to the EIS, providing details and updates on a regular basis from that point. Since then, more than 179 countries have reported the appearance of the cases within their borders, and, after collecting information and laboratory-confirmed evidence of the virus, all have reported and maintain updates to the WHO through the EIS. This information is updated in the Disease Outbreak News, which is openly shared with the public on the WHO webpage.12 The orderliness and openness of the process established under the IHR (2005) reflects how countries have utilized pandemic influenza planning and other developments to successfully and confidently report their findings.

Conclusions: Using the Full Power of the IHR

The IHR (2005) provides an unprecedented opportunity for its states parties to move toward a “larger freedom,” to build parity among countries to share information, and to enjoin in true partnership that has implications for ensuring better global health and security in the twenty-first century (Fidler and Gostin, 2006; Rodier et al., 2007).

This truly is a paradigm shift, to a more transparent and cooperative operations, to respecting that the world needs to share in the information, to move away from the fear that reporting of events leads to plummeting reputation, and to be a true partner in ensuring global health security, not merely in words but in action and trust.

There is certainly the risk of losing momentum and interest if assistance does not come in a timely manner and is not appropriately administered. Here is the chance to follow the conventional approach in guidance, assessment, training, and setting norms and standards; it is also the entry point to using the new tools of the twenty-first century.

No longer can information be sequestered and suppressed to a larger extent; the Internet has opened up access to a multitude of information sources, from web searches and resource bundling, to surveillance tools that cross the physical and cultural divides. Internet surveillance tools offer capabilities for countries that can now connect and receive information (Wilson and Brownstein, 2009). During the SARS outbreak in 2003, it was the World Wide Web, electronic media, personal communications, and NGOs that provided information on key sources of the disease outbreak, far more information than that from the normative formal sources, which provided only 39 percent of the reports (Heymann, 2006). The way the public receives and looks for information has also moved from the normal news and reporting sources.

There is a benefit to linking with local, regional, and supraregional networks such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the GOARN, the Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation (Kimball et al., 2008), the global health security initiatives, and the International Association of Public Health Institutes (Koplan et al, 2006), because they are key partners in the capacity-building, information sharing and sustainment for IHR core capacity preparedness and implementation. The WHO can only do so much at the global and country levels; these associations bring awareness, recognition, and real partnership to participating countries. The global public health community must find ways to incentivize application and encourage compliance, for clearly the IHR (2005) form a unique political and legal framework for all countries and partners in helping and informing each other. In the twenty-first century, success means using all means possible and committing to the long haul of building and sustaining, over and over and over again.

IMPLEMENTING THE REVISED INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS IN RESOURCE-CONSTRAINED COUNTRIES: INTENTIONAL AND UNINTENTIONAL REALITIES

Oyewale Tomori, D.V.M., Ph.D.13

Redeemer’s University

The revised International Health Regulations (hereinafter, the IHR), adopted by the WHA on May 23, 2005 (WHO, 2008b), represent a refreshing and bold departure from their largely impotent predecessors. However, the successful implementation of the IHR depends on addressing the concerns of policy makers from resource-constrained countries.

Trade was once the focus of the IHR, which prior to 2005 sought to limit the spread of a few diseases considered to be of importance to international trade and travel. The revised IHR emphasize public health risks, irrespective of origin or source, due to naturally occurring infectious or noncommunicable diseases and the suspected intentional or accidental release of biological, chemical, or radiological substances. The intent of the IHR is clear and unambiguous: “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease, in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” (emphasis added).

Two recent events in Africa illustrate the status of implementation of the revised IHR. The first occurred early in 2007, when the Nigerian government voluntarily confirmed the first human case of avian influenza (Guardian, 2007); that government had, in February 2006, officially reported the first outbreak of H5N1 influenza in poultry (Vasagar, 2006). The second event occurred early in 2008, when the government of Zimbabwe, after initially denying a cholera epi-

demic, later publicly, but reluctantly, confirmed that an outbreak was ongoing in that country (BBC, 2008b; Wang, 2008). While these events might be interpreted as evidence of progress in disease reporting since the introduction of the IHR, it can also be argued that these actions by the Nigerian and Zimbabwean governments resulted from political considerations rather than out of concern for the international spread of diseases.

Reception of the IHR (2005) by Resource-Constrained Countries

Interest in international tourist traffic and trade naturally determines a given country’s interest in implementing the revisions to the IHR. For resource-constrained countries, which attract few tourists and export minimum commodities, it is perhaps understandable that the IHR are accorded minimal priority. Rather, a large proportion of policy makers in resource-constrained countries perceive that the emphasis of the IHR on the international spread of disease evinces little concern regarding the burden of infectious diseases on the nations in which they occur. This perception is fueled by a long-standing history of selective application and implementation of global health policies in order to support the interests of countries in the developed world. For example,

-

Disproportionate international reactions to disease outbreaks and other medical emergencies in developed countries—for example, the recent detection of imported cases of traveler-associated Lassa or yellow fever in Europe (WHO, 2006b)—as compared with those taking place in developing countries (the current cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe (WHO, 2008a) and the deaths of children from suspected paracetamol poisoning in Nigeria (BBC, 2008a);

-

Preservation of the smallpox virus by the United States and Russia (WHO, 2009);

-

Studies that note savings by developing countries as a key reason to support global disease eradication initiatives; and

-

Insectide spraying in the cabins of planes leaving resource-constrained countries, whereas similar action is not taken on inbound planes.

In the same light, policy makers in resource-constrained countries perceive that undue and disproportionate emphasis is placed on providing resources to respond to disease outbreaks that might spread internationally, as compared with resources marshalled within national boundaries to prevent outbreaks in the first place. It is therefore not surprising that such policy makers provide only passive support for the implementation of global initiatives such as the IHR.

A Nigerian proverb states that “it is the fear of the stigma that makes men swallow poison.” Accordingly, some governments would rather watch an infectious disease rage among their citizens than report its existence and risk interna-

tional ridicule and global isolation. This principle is expressed when, as in the recent case of cholera in Zimbabwe discussed earlier in this paper, a government denies the existence of an outbreak, minimizes its severity when faced with incontrovertible evidence of its existence, or lays the blame for an outbreak on another government or agent.

Obstacles to Implementation in Africa

Article 5.1 of the revised IHR states:

Each State Party shall develop, strengthen and maintain, as soon as possible but no later than five years from the entry into force of these Regulations for that State Party, the capacity to detect, assess, notify and report events in accordance with these Regulations, as specified in Annex 1. (WHO, 2006a)

Given the current rate of progress in the (African) state parties, and, in many cases, within resource-constrained countries in general, the target is not likely to be achieved within the specified time frame, nor sustained thereafter, if the following issues are not resolved. They include:

-

Ineffective and unreliable national disease surveillance systems,

-

Inadequate political will and committment to disease control and prevention,

-

Poor regional networking for disease reporting and response, and

-

Donor partner priorities that may be at variance with national priorities.

Surveillance Systems

In many African countries, major obstacles to an effective disease surveillance and control system include insufficient funding, inadequate staffing, inappropriate or insufficient training of existing personnel, and lack of appreciation of the cost-effectiveness of a reliable disease surveillance system in health care delivery. Public health laboratories that conduct infectious disease surveillance in Africa tend to be poorly staffed and often lack basic equipment and supplies; few are able to communicate or receive epidemiological information or transport laboratory specimens in a timely way.

In many African countries, the infectious disease surveillance system functions vertically, having been established to monitor specific vaccine-preventable diseases such as poliomyelitis, cerebrospinal meningitis, cholera, or yellow fever. This ad hoc system of disease-specific surveillance programs has resulted in a lack of integration of disease surveillance and control, a disdain for developing and building local capacity, and a penchant for acquiring imported technologies. Indeed, it can be said that disease-specific surveillance programs have prevented the establishment of reliable and comprehensive national disease surveillance systems.

Vertical surveillance programs may employ disease-specific data collection tools, reporting formats, and surveillance guidelines for donor-targeted diseases, but these capacities are rarely used to monitor or control endemic diseases. At an operational level, it is the same person or team who performs all surveillance activities, leading to a duplication of efforts with increased workload for staff and inefficient utilization of available resources, or to the neglect of the endemic diseases, as the staff or team focus on donor targeted diseases (these are diseases of priority importance in a donor country, which are often of low priority in the recipient country). For example, the United States may wish to provide greater support for studies on anthrax, monkeypox, and so forth—diseases with higher bioterrorism potential—than on measles, yellow fever, and cerebrospinal meningitis, diseases that still ravage and decimate populations in resource-constrained countries. Moreover, many vertical interventions for disease surveillance and control have not been sustained due to lack of appropriately trained local staff. Since most epidemics in Africa originate at the health district level, locally based, comprehensive disease surveillance—and the sense of ownership that goes along with it—would be optimal.

Political Will and Commitment

A general lack of political will and commitment to public health is evidenced by the inadequate consideration of and financial support for health issues by most African governments at all levels. The leadership of resource-constrained countries must appreciate that global health depends upon a commitment by each country to protect its citizens from disease. Such a commitment is practiced in those developed countries in which citizens’ welfare is a bedrock political issue.

Networking

The impact of diseases, such as yellow fever and cholera, which are endemic in certain regions of the world could be minimized if the countries in the region work together through networking and sharing of data and expertise. However, for reasons of territorial integrity and an absence of formal collaborative agreements, health officials may be reluctant to share information on priority communicable diseases with their counterparts in other countries.

Regulatory Constraints

Donor agencies impose inflexible regulatory constraints that hamper maximum utilization of human and financial resources for integrating disease surveillance systems. In some resource-contrained countries, funds allocated for activites under a donor-funded tuberculosis project may not be applied for activities under, for example, an HIV/AIDS project, even if the outcome of such an

activitiy will have mutual benefit for both projects. At the individual level, there is a dearth of highly qualified professionals in many resource-constrained countries; therefore, the few available professionals must serve in other capacities, sometimes not directly related to their fields of expertise. The activities of such an individual employed under a donor-funded project are strictly limited to the confines of the donor project. For example, a virologist (who may be the only one in the country) employed under a donor-funded project dealing with measles may not be allowed to place his expertise at the service of his government during an epidemic of yellow fever.

Enabling Implementation of the IHR 2005 in Resource-Constrained Countries

If the revised IHR are to be successfully implemented in resource-limited countries, there will be a need to correct the misperception that the emphasis of the revised IHR is on the international spread of disease, while the issue of the burden of infectious diseases on the resource-constrained nations is of secondary priority.

The following efforts will help achieve that goal.

Emphasize Disease Prevention at the National Level

Equal emphasis must be placed upon the national and international spread of diseases. Growing up in Africa, I learned that keeping our individual compounds clean ensured the cleanliness of our entire village; so it must be with our “global village.” Thus, the purpose and scope of the revisons to the IHR should be restated as follows:

-

Prevent both the national and international spread of disease,

-

Protect against both the national and international spread of disease,

-

Control both the national and international spread of disease, and

-

Provide a public health response to both the national and international spread of disease (emphasis added).

Build National Capacity for Disease Prevention

The practice of “dangling the carrot” of international resources for responding to a disease outbreak (e.g., vaccines, funding, and foreign expertise) as an incentive for reporting such an outbreak may undermine the determination of resource-constrained countries to develop, strengthen, and maintain national core surveillance and response capabilites. Moreover, it is far more efficient to contain disease outbreaks than to respond to full-blown epidemics. Therefore, greater consideration should be given to encouraging countries to develop capacity to

report, detect, and investigate suspected infectious disease outbreaks and thus prevent sporadic cases (especially of known diseases) from escalating to epidemics, and more resources (training, supplies, funds, and foreign expertise) should be provided for establishing and maintaining disease surveillance systems at the national level.

Sustainable Surveillance: National Capacity-Building

The polio eradication initiative in Africa has enabled the establishment of a reliable acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance system, backed by an African region-wide laboratory network. The 16-member polio laboratory network, accessible to the 46 countries in the Africa WHO region, has provided timely and accurate results to national polio control programs. The success of the polio laboratory network has led to the establishment of other disease-specific laboratory networks and surveillance systems. Five additional laboratory networks (measles, yellow fever, and rubella; HIV/AIDS; pediatric bacterial meningitis; rotavirus; human papillomavirus) currently operate in the Africa region with minimal collaboration. These networks provide a foundation upon which comprehensive disease surveillance capacity could be built to enable successful implementation of the IHR.

Surveillance systems will be improved only if their importance to disease control is recognized and appreciated. Reliable disease surveillance can help to improve the prediction, early detection, and control of epidemics; inform the rational allocation of resources; and guide the monitoring and evaluation of health interventions. Building and maintaining robust, national, integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) systems for emerging zoonoses and other communicable diseases can considerably reduce morbidity, mortality, and disability associated with these diseases. Achieving this result will require:

-

Management and application of surveillance data;

-

Communication systems to effectively transmit surveillance data and epidemiological information;

-

National, subregional, and regional laboratory networks and their capacity for involvement in IDSR activities;

-

Epidemic early warning and rapid response systems, including the preparation and implementation of national emergency preparedness and response plans;

-

Training of health workers to participate in IDSR, including the integration of IDSR in training curricula and materials; and

-

Research (including operational research) to improve IDSR in resource-limited countries.

Conclusion

Article 5.3 of the revised IHR states that the WHO shall assist state parties, upon request, to develop, strengthen, and maintain the capacities to detect, assess, notify, and report disease events of international concern. Many countries need far more guidance than WHO has yet provided, including a clear understanding of their own needs. A greater effort must be made to enable each participating country to own and control its surveillance system within the global network, thereby supporting the successful and timely implementation of the IHR.

VIRAL SOVEREIGNTY, GLOBAL GOVERNANCE, AND THE IHR 2005: THE H5N1 VIRUS SHARING CONTROVERSY AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR GLOBAL HEALTH GOVERNANCE

David P. Fidler, J.D.14

Indiana University

Introduction

This workshop emphasizes the importance of the revised International Health Regulations 2005, hereinafter IHR 2005 (WHO, 2008), as a governance instrument for the challenges globalization presents to countries and international organizations with respect to the movement of pathogens and their hosts. As Dr. David Heymann, then of the WHO, made clear in his presentation, the IHR 2005 represent a significant advance in global health governance, particularly with respect to threat posed by communicable pathogens (Heymann, 2008). My mandate for this workshop was to address the implications for the H5N1 virus sharing controversy for the IHR 2005 specifically and for global health governance generally.

In fulfilling this mandate, I explore why the H5N1 virus sharing controversy raises hard questions about the IHR 2005 and its future. This exploration involves:

-

Reviewing the IHR 2005’s importance as an innovative global governance regime;

-

Examining how the H5N1 virus sharing controversy represents a significant problem for the IHR 2005 and the future of global health governance;

-

Considering what the virus sharing controversy reveals about the nature of public health as a foreign policy issue;

-

Analyzing how expected global trends in international politics might affect the issues raised for the IHR 2005 by the virus sharing controversy;

-

Considering the implications of the influenza A (H1N1) outbreak in April-May 2009 for the virus sharing controversy and the IHR 2005; and

-

Reflecting on the intent of the IHR 2005, the realities facing this global governance regime, and the prospects for more effective implementation in the years ahead.

The IHR 2005: A Radical New Instrument of Global Health Governance

The story of the emergence, negotiation, and implementation of the IHR 2005 is, on many levels, a fascinating case study of the evolution of a radical “new way of working” with respect to global health governance. The IHR 2005 have their roots in the nineteenth-century origins of diplomacy on international health (i.e., the international sanitary conferences and conventions), began their life as a WHO governance mechanism in the form of the International Sanitary Regulations promulgated in 1951, and broke decisively from the International Health Regulations adopted in 1969 (IHR 1969; Fidler, 2005).

In the interests of brevity, I highlight five of the most significant changes WHO member states negotiated in adopting the IHR 2005 and moving this regime away from the antiquated and stagnated set of rules the IHR 1969 had become by the mid-1990s, when the IHR revision process began. Although incomplete as a description of the IHR 2005, these five changes suffice to communicate how radically different the IHR 2005 are from any regime in the history of the use of international law for public health purposes.

First, the epidemiological and political scopes of the IHR 2005 have been expanded significantly. From the epidemiological perspective, the IHR 2005’s scope has increased in three ways:

-

Unlike the IHR 1969, which applied to a short list of specified infectious diseases (cholera, plague, and yellow fever), the IHR 2005 apply to a list of specific communicable disease threats and any communicable disease event that may represent a public health emergency of international concern (IHR 2005, Annex 2). Thus, WHO member states must report to WHO any disease event that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern (IHR 2005, Article 6).

-

The IHR 1969 only applied to communicable diseases, but the IHR 2005 apply to disease events that involve communicable pathogens, chemical substances, or radiological agents (IHR 2005, Article 7).

-

The IHR 2005 apply to the intentional use of biological, chemical, or radiological agents, and thus are designed to facilitate responses to terrorist or state uses of weapons of mass destruction. The IHR 1969 had no such application.

Politically, the IHR 2005’s scope also expanded. The best illustration of the politically expanded scope appears in the IHR 2005’s application to biological, chemical, and radiological agents—an application that makes the IHR 2005 important in traditional national security terms. In addition, WHO and many WHO member states promoted the IHR 2005 as an instrument that could help countries strengthen “global health security,” a concept that gave “security” a broader meaning and elevated the importance of health in achieving human, national, and global security. Neither the early international sanitary conventions nor the IHR 1969 had ever been associated with concepts of security in the manner the IHR 2005 have been.

Second, the IHR 2005 impose obligations on WHO member states to develop and maintain minimum core capabilities in the areas of surveillance and response (IHR 2005, Articles 5, 13; Annex 1). The most the IHR 1969 required in connection with public health capabilities involved facilities at points of entry and exit (for example, airports, seaports). The minimum core capacities contained in the IHR 2005 as binding obligations are unprecedented in the history of this area of international law on public health.

Third, the IHR 2005 empower WHO to collect and use information from nongovernmental sources (IHR 2005, Article 9). Under the IHR 1969, WHO could only officially use information it received from governments, and this limitation proved one of the greatest weaknesses of the IHR 1969 because governments routinely failed to provide WHO with information about outbreaks of diseases subject to the regulations. The IHR 2005 allow WHO to receive information from nongovernmental sources and seek verification of such information from governments (IHR 2005, Article 10). This change in the kinds of information WHO can officially use radically changes the dynamic of the flow of information to WHO about disease events and provides WHO with leverage it could not previously utilize.

Fourth, the IHR 2005 authorize the WHO Director-General to declare a public health emergency of international concern (IHR 2005, Article 12). As noted earlier, WHO member states must report to WHO any disease events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern, but the IHR 2005 give the WHO Director-General—not WHO member states—the power to declare the actual existence of such an emergency. In addition, this power permits the WHO Director-General to declare such an emergency over the opposition of WHO member states directly affected by the disease event in question.

Fifth, the IHR 2005 incorporate human rights concepts and require WHO member states to apply their public health powers in conformity with the principles of international human rights law.15 The IHR 1969 contained no such effort to bring human rights concepts to bear on cooperation on infectious disease control.

The mere existence of radical changes in the IHR 2005 does not guarantee that the IHR 2005 will radically change global health. As explored more below, serious concerns exist about whether the implementation of the IHR 2005 will actually live up to the promise the radical changes portend. Despite this caveat, evidence does exist that suggests the potential of the IHR 2005 as a global governance regime.

First, the successful global response to the 2003 SARS outbreak was based, in essence, on a rollout by WHO of the concepts and strategies that would eventually be adopted in the IHR 2005. Second, in the brief time the IHR 2005 have been in force (i.e., since June 2007), WHO is convinced of their improved utility over the IHR 1969, particularly in terms of gathering information about disease events, seeking verification from governments, and working more closely with countries to respond to actual and potential disease threats.

The H5N1 Virus Sharing Controversy and the Revised IHR

Indonesia’s Exercise of Viral Sovereignty