The Context for America’s Climate Choices

The United States lacks an overarching national strategy to respond to climate change.

America’s response to climate change is ultimately about making choices in the face of risks: choosing, for example, how, how much, and when to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and to increase the resilience of human and natural systems to climate change. These choices will in turn influence the rate and magnitude of future climate change and its impact on people and many things that people care about. Each course of action carries potential benefits and risks, only some of which can be fully anticipated and quantified. A key question surrounding America’s climate choices is thus how we as a society perceive, evaluate, and respond to risk. This question is complicated by the diversity of people, communities, and interests affected by climate change (and by many of the proposed responses to climate change), by their different perceptions and judgments of and tolerances for risk, and by the fact that climate change is an issue that spans local to global scales and multiple generations.

This report, the final volume of the America’s Climate Choices (ACC) suite of activities (Box 1.1), offers advice on how to weigh the potential risks and benefits associated with different actions that might be taken to respond to climate change, and how to ensure that actions are as effective as possible. America’s climate choices will ultimately be made by elected officials, business leaders, individual households, and other decision makers across the nation; and these choices almost always involve tradeoffs, value judgments, and other issues that reach beyond science. The goal of this report, and of the entire ACC suite of activities, is to ensure that the nation’s climate choices are informed by the best possible scientific knowledge and analysis, both now and in the decades ahead.

This chapter briefly reviews some key elements of the current context in which America’s climate change must be made. Chapter 2 reviews current scientific understanding of the causes and consequences of climate change. Chapter 3 describes some of the features of climate change that make it such a unique, challenging issue to address. Chapter 4 explores the concept of iterative risk management as an over-

BOX 1.1

The America’s Climate Choices Study

In 2008, Congress commissioned the National Academy of Sciences to: “investigate and study the serious and sweeping issues relating to global climate change and make recommendations regarding what steps must be taken and what strategies must be adopted in response to global climate change, including the science and technology challenges thereof.” In response to this mandate, and with financial support from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the America’s Climate Choices suite of activities was established. A Summit on America’s Climate Choices held in March 2009, and independent panels were convened to study and produce reports focusing on four specific aspects of responding to climate change: Advancing the Science of Climate Change,a Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change,b Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change,c and Informing an Effective Response to Climate Change.d

The panel reports offer a detailed analysis of possible actions and investments in each of these four realms—for instance, regarding specific technologies and policies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, needs and opportunities for adapting to climate change impacts, and key research needs in different areas of climate change science (see Appendix C for more details about the content of the panel reports). This final report by the Committee on America’s Climate Choices draws on the information and analysis in the four panel reports, as well as a variety of other sources, to identify cross-cutting challenges and offer both a general framework and specific recommendations for establishing an effective national response to climate change.

a National Research Council (NRC), Advancing the Science of Climate Change (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010).

b National Research Council (NRC),Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change(Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010).

cNational Research Council (NRC),Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change(Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010).

d National Research Council (NRC), Informing an Effective Response to Climate Change(Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010).

arching framework for responding to climate change. Chapter 5 offers recommendations for the key elements of an effective, robust U.S. response.

GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION TRENDS

Despite an international agreement signed by the United States and 153 other nations in 1992 to stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system,”1 GHG emissions have continued to rise. Energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions constitutes roughly

BOX 1.2

Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases and Aerosols

International negotiations and domestic policy debates have focused largely on reducing CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, both because these emissions account for a large fraction of total GHG emissions and because they can be estimated fairly accurately based on fuel-use data.a This report follows suit by focusing primarily on energy-related CO2 emissions. It is important to recognize, however, that there are other important sources of CO2 (such as tropical deforestation), and there are other compounds in the atmosphere that affect the earth’s radiative balance and thus play a role in climate change.

This includes long-lived GHGs such as methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated compounds (which arise from a variety of human activities including agriculture and industrial activities). It also includes shorter-lived gases that are precursors to tropospheric ozone (which directly affects human health, in addition to influencing climate), and a variety of aerosols that can exert either warming or cooling effects, depending on their chemical and physical properties. Some of these other compounds are explicitly included in climate policy negotiations and emissions reductions plans, but in general it is much more difficult to measure and verify reductions in emissions of many of these substances than for CO2.b See NRC, Advancing the Science of Climate Change and Limiting the Magnitude of Climate Change for more extensive discussion of these other gases and aerosols.

a It should be noted, however, that there is as yet no sufficiently accurate way to verify countries’ self-reported estimates using independent data. A recent study (NRC, Verifying Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Methods to Support International Climate Agreements, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010) recommended a set of strategic investments that would improve self-reporting and provide a verification capability within 5 years.

b NRC, Verifying GHG Emissions.

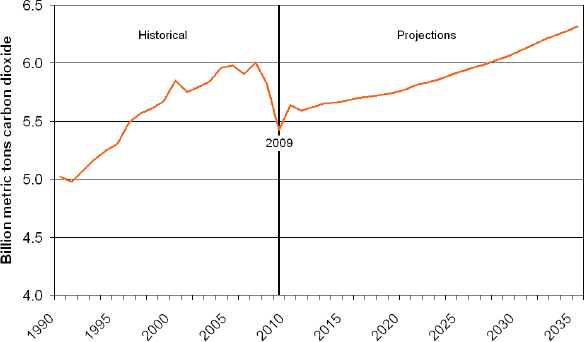

83 percent of total U.S. GHG emissions2 and thus will be the primary focus of the discussion in this report (non-CO2 GHGs are discussed briefly in Box 1.2). Figure 1.1 shows recent and projected energy-related CO2 emissions for the United States. The increase in emissions over the past few decades occurred despite the fact that the “intensity” of America’s CO2 emissions (the amount of emissions created per unit of economic output, often presented as emissions per dollar of GDP) decreased by almost 30 percent.3 Thus, the general tendency for industrialized nations to become more efficient and less carbon intensive has slowed but not prevented the growth of domestic CO2 emissions.

The upward trend in U.S. emissions has been punctuated by brief declines, usually during economic downturns. By far the most significant of these downturns was the roughly 6 percent decrease in energy-related CO2 emissions in 2009, related to the economic recession.4 However, the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s latest

FIGURE 1.1 Energy-related U.S. CO2 emissions for 1980-2009 (estimated) and 2010-2035 (projected). Given in billion metric tons CO2. The long-term upward trend in emissions has been punctuated by declines during economic downturns, most notably around 2009. SOURCE: Adapted from Energy Information Administration (EIA), International Energy Outlook, Report # DOE/EIA-0484(2010) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy, 2010, available at http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/, accessed March 4, 2011).

projections are that emissions return to an upward trend in 2010, and that under a “business-as-usual” scenario through 2035 (that is, assuming no major actions to reduce domestic GHG emissions or additional major economic downturns), CO2 emissions will grow by an average of roughly 0.2 percent per year.5 This is a slower growth rate than that of the past three decades, but it does indicate that emissions will exceed pre-recession levels by the year 2028, and by the year 2035 they will be about 8.5 percent higher than pre-recession levels.

Recent studies have highlighted the commitments to further climate change that are implied by construction of new, long-lived infrastructure (e.g., electricity production facilities, highways). Once constructed, the emissions from these facilities can be locked in for as much as 50 years or more. This is an especially serious concern in regards to rapidly developing countries, where huge investments in new energy generation and energy use systems are being made.6 As a result, global GHG emissions are projected to increase steeply. The U.S. Energy Information Administration esti-

mates that by 2035, global emissions will be more than 40 percent larger than in 2007 in the absence of aggressive policies to reduce emissions, with most of the increase expected to occur in developing economies.7

As a signatory to the Copenhagen Accord in 2009, the United States has endorsed an effort to work with the international community to prevent a 2°C (3.6°F) increase in global temperatures relative to pre-industrial levels (see Box 1.3).8 As part of this accord, the Obama Administration set a “provisional” target of reducing U.S. GHG emis-

BOX 1.3

International Context

The ACC studies focus primarily on domestic action, but climate change is an inherently global problem, and U.S. response strategies must be formulated in the context of international agreements and the actions of other nations. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has thus far been the most visible arena for international negotiations on climate change. The only major binding agreement to emerge from the UNFCCC process—the Kyoto protocol—was never ratified by the United States and will expire in 2012. There is no comprehensive agreement for governing response to climate change at the international level. Instead, we have seen the emergence of a loosely coupled “complex” of activities with no clear core, which includes, for instance, bi-lateral initiatives (e.g., the U.S.-China Partnership on Climate Change), clubs of countries that pledge cooperative efforts (e.g., G-8+5 climate change dialogue, Major Economies Forum, Asia Pacific Partnership), and programs of specialized UN agencies (WMO, UNEP, UNDP, FAO) and other international entities (GATT, WTO, World Bank).a

Climate change science is also an inherently international enterprise that has been greatly advanced through programs that coordinate and facilitate cooperative multi-national research efforts, such as the World Climate Research Program. Global observing systems, which provide crucial information about climate system variability and long term change, are advanced through cooperative efforts such as the Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GOESS). Also of great importance is the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which synthesizes and translates research developments into information that is useful for policy makers. The United States has been a major contributor to, and beneficiary of, all of these research, observational, and assessment activities.

a R. O. Keohane and D. G.Victor, The Regime Complex for Climate Change. Discussion Paper 2010-33. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements, 2010).

sions in the range of 17 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2020. Given the GHG emission projections discussed in the preceding section, it is clear that the United States will not be able to meet such a commitment without a significant departure from “business-as-usual.”

The federal government has adopted some policies (such as subsidies and tax credits) to catalyze the development and implementation of climate-friendly technologies, and there are also a range of voluntary federal programs in place to encourage energy efficiency and GHG emission reductions. More comprehensive federal-level legislation remains stalled. In June 2009, the House of Representatives passed the American Security and Clean Energy Act, which would have established a cap-and-trade system designed to lower U.S. GHG emissions by 17 percent by 2020 and 80 percent by 2050. A similar bill failed to reach the Senate floor, however; and following the 2010 mid-term elections, the prospects of any significant climate legislation being passed in the near future have diminished further.

In 2007 the U.S. Supreme Court instructed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that it is required under the Clean Air Act to regulate emissions of CO2 and five other greenhouse gases if it finds that such emissions threaten the public health and welfare.9 In 2009 the EPA issued such a finding and, as a consequence, the EPA is currently developing regulations on GHG emissions from newly constructed or modified power plants and industrial sources;10 recently, together with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, it issued a coordinated set of fuel economy and GHG emissions standards for light-duty vehicles. However, there are many obstacles in the path to EPA regulation (including, for example, potential congressional legislation that would delay or rescind EPA’s authority, and litigation likely to follow rulemaking efforts that would use the judiciary to do the same). Thus the timing and character of regulatory programs to control GHG emissions are by no means certain.

Despite the current lack of comprehensive national policies, early actors at other levels of government and in the private sector are advancing policies and commitments to reduce emissions and lessen impacts. In the private sector, many corporations have made commitments or developed action plans for significantly reducing emissions from their operations.11 More than 1,000 mayors have signed onto the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement, pledging to reduce their city’s overall emissions by 7 percent below 1990 levels by 2012.12 A majority of states have adopted some form of renewable portfolio standard,13 energy efficiency program requirements, or emissions reduction goal, and some have adopted or plan to adopt cap and trade systems to reduce GHG emissions (for example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative of the northeastern U.S. states, the Western Climate Initiative, the Midwest-

ern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord). The California Global Warming Solutions Act (AB32) enacted a sweeping set of GHG emission control programs for the state (and it survived a ballot proposition to repeal the Act in 2010).

Many states and communities have also developed policies to expand mass transit systems, discourage urban sprawl, increase efficiency, and tighten the energy provisions of building codes,14 and there are important developments being led by sub-national governments and nongovernment organizations in the development of protocols and registries for reporting and verifying GHG missions (e.g., the Climate Registry, the California Climate Action Registry, the Carbon Disclosure Project of ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability).15

Climate change adaptation planning efforts are also under way in a number of states, counties, and local communities.16 Adaptation strategies are being explored in climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture and water resources management, which have historically adapted to natural climate variability in ways that may reduce vulnerabilities to climate change. Several non-governmental organizations have also become active in promoting adaptation planning. In 2009, the White House Council on Environmental Quality, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration initiated an Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force to recommend adaptation initiatives both domestically and internationally. The U.S. intelligence community is assessing how climate change may affect national security (for instance, through geopolitical destabilization from water scarcity or sea level rise), and the U.S. military has begun to consider how climate change will affect their facilities, capabilities, and theatres of operation.17

The collective effect of these local, state, federal, and private sector efforts to limit and adapt to climate change is potentially quite significant but, as suggested by recent analyses, it is not likely to yield emission reductions comparable to what could be achieved with strong federal policies.18 Moreover, it is not clear if the current patchwork of initiatives will prove durable in the absence of an overarching federal policy. For example, evidence suggests that many early actors have been motivated at least in part by a belief that federal legislation on climate change is inevitable and that getting out in front of that legislation will offer a competitive advantage.19 Without a federal policy, emission cuts made in states with climate programs may be undermined by “leakage” to states without such programs, and varying policies across state lines may also lead to inefficiencies and market imbalances. It also possible, of course, that some commitments made during periods when the economy was growing will be reconsidered as the economy struggles to recover from a recession.

CHAPTER CONCLUSION

The collective effect of local, state, and private sector efforts to respond to climate change is significant and should be encouraged, but such efforts are not likely to be sufficient or sustainable over the long term without a strong framework of federal policies and programs that ensure all U.S. stakeholders are working toward coherent national goals.

As described briefly in this chapter and explored in the ACC panel reports, there are already many efforts under way across the United States (led by state and local governments, and private sector and nongovernmental organizations) to reduce domestic GHG emissions, to adapt to anticipated impacts of climate change, and to advance systems for collecting and sharing climate-related information. Although there can be real benefits to having these actions take place in such a decentralized fashion,20 in the judgment of the committee the many risks posed by climate change—coupled with the scale and scope of responses needed to respond effectively—demand national-level leadership and coordination. The appropriate balance between federal and nonfederal responsibilities depends on the domain of action. The ACC panel reports provide detailed discussion about the different types of federal leadership and coordination efforts that are most needed in the domains of advancing scientific understanding, limiting the magnitude of climate change, adapting to its impacts, and informing effective decisions.