2

Systems of Care for MNS in Sub-Saharan Africa

The delivery of care for mental health, neurological, and substance use (MNS) disorders, including mental health care, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is a story of constraints, rather than opportunity. The funding, personnel, training, and equipment available are insufficient to provide the level of care that policy makers and healthcare providers would prefer, according to many speakers and participants (WHO, 2001). In that sense, the delivery of services in the region can be seen as a kind of ongoing crisis-management environment, complete with rationing and triage (Prince et al., 2007).

THE MNS TREATMENT GAP

A large proportion of patients with MNS in resource-poor countries do not receive appropriate treatment for their condition. Known as the “treatment gap,” it is defined as the proportion of people with a disease or condition who require treatment, but do not receive it. The gap tends to be much higher in developing versus developed countries and for rural versus urban populations. A recent World Health Organization (WHO) study of 14 countries found that in developed counties, the treatment gap, or percentage of serious cases that did not receive treatment in the previous 12 months, ranged from 35 to 50 percent. That number rose to 76 to 85 percent for the developing, low- and middle-income countries participating in the study (Demyttenaere et al., 2004) (see also Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 12-Month Treatment of Physical and Mental Disorders in High-Income and Low- and Middle-Income Participants in the World Mental Health Survey

Patel pointed out that in the poorest countries in the world, up to 90 percent of individuals with the most severe mental disorders—such as serious depression, psychosis, and epilepsy—do not even receive the most basic care (WHO, 2001). He said this does not mean individuals do not access care, it means that when they do access care, 90 percent do not receive the treatments known to be effective. Therefore, when patients present themselves for treatment, the symptoms may be treated, but the underlying cause is ignored. For example, if a patient presents with sleeplessness, fatigue, or soreness—all common symptoms associated with depression—the patient is often treated with hypnotics, tonics, or analgesics rather than being evaluated for the underlying cause of these symptoms.

In Tanzania, only 5 to 10 percent of individuals with epilepsy receive appropriate and adequate therapy. The treatment gap for epilepsy in developing countries has been mainly attributed to inadequately skilled personnel, cost of treatment, cultural beliefs, and unavailability of antiepileptic drugs, although lack of accessible health facilities has also been noted (Baskind and Birbeck, 2005; Mbuba et al., 2008). Other age-related MNS disorders on the rise in Tanzania, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, are also poorly recognized by healthcare

workers (Winkler et al., 2010). The lack of human resources and the difficulty of retaining staff, especially in rural areas, was an important obstacle that a number of the participants said worsened the treatment gap in SSA.

Workshop participants stressed that treatment gaps do not exist because of a lack of data on treatments. Substantial scientific data are available on the efficacy of treatments for MNS disorders. The problems are in getting appropriate diagnoses for particular conditions and in putting adequate resources and systems in place so proper care can be delivered. Overall, participants agreed that the failure to diagnose and appropriately treat MNS disorders in SSA is driven by multiple factors. These include gaps in the knowledge, training, and availability of healthcare workers combined with an inability and reluctance of MNS patients to access the healthcare system for treatment.

Community Distrust

As a result of the treatment gap and a strong influence of traditional medicine in certain communities, Western medical practices are sometimes viewed skeptically or at times negatively by community members. “Many people, including patients, are aware that health institutions can offer very little for chronic neurological disorders,” said Katabira. “There are shortages of specialists, physicians, doctors, and nurses…. [Additionally,] rehabilitation services are only available in big urban centers, yet [they] are most needed at the community level.” There have also been incidents where treatable disorders have been poorly managed, with resulting poor outcomes. “This gives negative feedback to the community,” said Katabira, driving patients back to traditional healers and remedies.

HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CHALLENGES

Workforce Issues

Availability of Skilled Professionals

Care for MNS disorders hinges on the availability of trained professionals, Patel said. Unfortunately, low-income African countries have few of these skilled professionals available to treat the large

numbers of persons with MNS disorders. In the clinical neurosciences (neurologists, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons), except for South Africa, the mean ratios for countries that have these medical specialists are 1 neurologist for 1 million to 2.8 million people (versus 4 per 100,000 in Europe); 1 psychiatrist for 900,000 people (versus 9 per 100,000 in Europe); and 1 neurosurgeon for 2 million to 6 million people (versus 1 per 100,000 in Europe). Most clinical neuroscience services are located in the capital cities, often the largest urban areas, where the professionals also often lecture at medical schools. As a result MNS patients often must travel long distances to consult with a doctor in the city (Silberberg and Katabira, 2006).

The absence of trained professionals is not isolated to a particular country, but rather it is widespread throughout SSA. For example, in Cameroon, there was one neurologist in 1988; by 1995 there were two and by 2005 a total of five. They all practiced in the big cities of Yaounde and Douala, where 5 million of Cameroon’s 18 million people lived. Currently, there are 10 neurologists, 7 neurosurgeons, and 1 neuroradiologist (WHO, 2004). In Kenya, with a population of 38 million, 22 psychiatrists work for the government, 25 work at universities or level-6 hospitals, and another 25 are in private practice. There are approximately 500 psychiatric nurses, though the numbers are not confirmed. In Tanzania, the doctor–patient ratio is the highest in East Africa at 1:33,000, with only 60 physicians providing care. There are 3 neurologists, 6 neurosurgeons, and 15 psychiatrists for the entire country (Winkler et al., 2010).

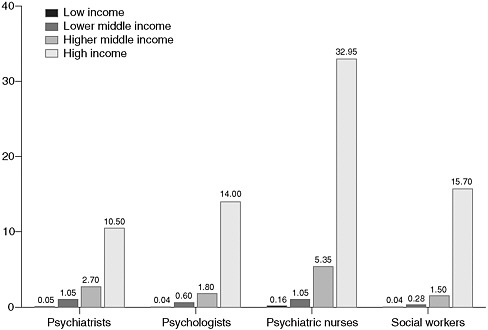

As noted in Figure 2-1, the scarcity of human resources for mental health in low- versus high-income countries is equally low. Patel observed that the number of specialists per 100,000 people is so small as to be nonexistent when compared to the higher numbers seen in middle-and high-income countries. Furthermore, “what you can see on this chart is less important than what you cannot see. Low-income countries have so few of these professionals that these bars are not even visible. The difference with high-income countries is often 200 times. And this applies to more or less all professionals.” Patel continued to explain, “The worst part of this story is that due to migration of professionals, the difference is widening rather than narrowing.” In the lowest income countries, there are effectively no psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, or social workers available to treat patients with common mental health disorders.

FIGURE 2-1 Scarcity of human resources for mental health.

SOURCE: Saxena et al., 2007.

Availability of Trainees and Retention of Trained Workers

According to workshop participants there is a dearth of students being trained in MNS disorders, and the retention of trained specialists is a significant problem in SSA. Over the short- and long-term this will continue to have a negative impact on the availability of trained healthcare professionals. The absence of formal training programs and career paths in MNS disorders serves as a barrier. Many of the associated MNS disciplines are not represented in the medical universities that are affiliated with hospitals. Further, as Katabira of Makerere University aptly stated, “Unfortunately less than 10 percent of the people we train actually end up in public service where they are needed most.” Some individuals enter into private practice in the urban areas, but many leave the country entirely. This flight of specialists has many reasons, but largely comes down to the absence of incentives to stay and provide care through the existing healthcare systems—a problem that can be easily fixed through the establishment of new policies. Remuneration is

certainly one factor leading to the departure of many trained providers. In addition, the absence of resources and the limitations of facilities are also critical reasons, Katabira noted. When these highly trained practitioners leave the training environment and go out to the rural health institutions, they are unable to provide the care they have been trained to provide. For example, “a doctor who knows how to diagnose meningitis,” said Katabira, “is unable to do a lumbar puncture to confirm what type of meningitis it is and therefore provide appropriate antibiotics because the lumbar puncture kit last existed in the hospital some 10 years ago.” This leads to understandable frustration for caregivers, so they leave.

Another major challenge facing health systems in SSA is the international migration of health staff to developed countries or to better paying positions on the African continent. Paul Farmer, cofounder of Partners in Health, made the point that African nurses are not leaving because they want to leave their homes. They feel forced to leave because they are not given the resources they need to care for their patients nor are they provided with adequate salaries to support themselves. Farmer was quick to emphasize that it is not just the salary, but also the lack of resources, that drives skilled African workers and professionals away from their homeland. However, the establishment of student loan reimbursement/forgiveness programs that require service in underserved communities would help incentivize individuals to seek MNS training and practice in their home country.

Barriers to Treatment

Access to Treatment Facilities

Many barriers limit access to care for persons with MNS disorders in SSA. In addition to the stigma of brain disorders preventing a person’s desire to seek care, issues of money and transportation impact where the treatment occurs, who provides the treatment, and what treatments are made available.

SSA is made up of countries where the majority of the populations live in rural settings. Distances to health facilities are often quite far, and roads may be poor or nonexistent. It can be difficult for those who have not experienced the distances and conditions involved in Africa to understand just how tremendous this simple barrier of mobility and distance can be. Augustine Mugarura of the Epilepsy Support Association of Uganda described an example of a health center called Rubuguli in

southern Uganda. Patients travel an average of 15 to 20 kilometers (9 to 12 miles), often by foot, to the nearest healthcare unit. Unfortunately, no psychiatric services are provided at Rubuguli, so patients must travel to Kisoro hospital to receive care. The health center has no phone. Except for individuals with mobile phones, there is no way to communicate with the hospital if there is an emergency it cannot handle. A four-wheel drive vehicle—the fastest mode of transport available—takes 2 hours to travel between the Rubuguli health center and Kisoro hospital, and traveling by motorcycle taxi takes 4 hours.

Faced with these conditions, a 2-hour walk to a clinic and a 4-hour drive to a hospital capable of providing needed MNS services, it is no wonder that many stroke and physically disabled patients cannot access the care they require. As Katabira noted, “If they do, many are unable to honor follow-up appointments.” For patients who reach a hospital and are admitted, in-patient care can also negatively impact families because a member of the family needs to stay with the patient in order to provide them with basic bedside care. That removes a family member from the workforce and impacts their earnings.

Financing MNS

Assuming an accurate diagnosis is made, the patient then faces the challenge of paying for treatments and medicines. In low-income countries, health insurance is rare and care for MNS disorders is paid primarily out-of-pocket by families. Even if the government provides health services, families may need to pay for medications. The decision to treat can come down to a choice between medicine for one person or food for the family, which is particularly difficult for those in need of long-term treatment.

This is just one aspect of financing MNS disorders. There is also the broader picture whereby the low financial allocations from governments to support clinician training and purchase of diagnostic equipment and treatments greatly hinders initiating and maintaining quality treatment. Building off the available burden data, additional research would provide the necessary evidence to help support the development of MNS policies. However, resources are extremely limited throughout SSA. Therefore, strategies need to be established that will minimize resource expenditures.

OVERCOMING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CHALLENGES

Although there is little doubt that SSA, from a public health perspective, is in crisis, workshop participants were not without hope, and spoke repeatedly about the future—about reducing the treatment gap and improving the quality of care in the region for those suffering from MNS disorders. Participants spoke of quality care as not just the best treatments, but using those treatments in a flexible manner to meet the unique needs of the patient population in SSA.

The good news is that much is known about treating MNS disorders. Treatments are also broadly effective, and projects such as the Disease Control Priority Project have even modeled the cost-effectiveness for a range of treatments across many mental and neurological disorders (WHO, 2006c). What is missing is how to deliver that care and, particularly, how to integrate quality MNS care into the primary care delivery systems in various regions. The key to that, participants agreed, is collaboration, innovation, and the application of available technologies.

Closing the Human Resource Gap

With few physicians and specialists available to treat individuals with MNS disorders, workshop participants discussed strategies to help close the human resource gap that is present, especially in rural areas. As discussed during the workshop, one strategy is to try to increase the number of specialists who enter the field by recruiting individuals directly out of primary school and university. “We need to look for the future,” said Professor Alfred Njamnshi of the neurology department of the Central Hospital Yaoundé, Cameroon. The Pan African Association for Neurological Science has a program that sends individuals to primary and secondary schools, as well as universities, to talk about neurology, neurosurgery, and neuroscience, with the intent of leading students to careers in the field. However, as previously discussed, incentives, such as loan reimbursement/forgiveness programs, need to be established to help motivate clinicians to stay and work with underserved communities.

Workshop participants spoke of the need to do more than rely solely on a prospective and theoretical flow of new specialists. “If we rely solely on specialists we are never going to close the treatment gap, not now or indeed in the foreseeable future,” said Patel. Instead, workshop participants discussed models to better integrate MNS care into primary

care, using community health workers and possibly using technology to close the treatment gap.

Community-Based Care

Central to many of the success stories described during the workshop was the concept of community-based, rather than institutional, care, particularly for mental health care. According to the WHO Mental Health Report from 2001,

Community care has a better effect than institutional treatment on the outcome and quality of life of individuals with chronic mental disorders. Shifting patients from mental hospitals to care in the community is also cost-effective and respects human rights. Mental health services should therefore be provided in the community with the use of all available resources. Community-based services can lead to early intervention and limit the stigma of taking treatment. Large, custodial mental hospitals should be replaced by community care facilities, backed by general hospital psychiatric beds and home care support, which meet all the needs of the ill that were the responsibility of those hospitals. This shift toward community care requires health workers and rehabilitation services to be available at the community level, along with the provision of crisis support, protected housing, and sheltered employment (WHO, 2001).

Community-based care moves patients away from hospitals and allows them to be treated near or at their homes, and thus it is essential for the long-term care of chronic disabilities and disorders. “The highest standard of care anywhere in the world is going to be a complement with community health workers,” said Farmer, who outlined community-based care advantages as noted in Box 2-1.

Workshop participants discussed the fact that many community health workers are currently volunteers and suggested that, in order for this system to work, these people need to be paid. The idea is that workers who are paid are more likely to continue in their position and provide continuity of care, thereby reducing the need to train new workers. Providing opportunities for further skill training may be a way of retaining workers. An example of this is provided in Box 1-1, which describes epilepsy care in Tanzania.

Integrating MNS with Other Healthcare Measures

According to Inge Petersen from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa has begun to integrate, with success, some common mental disorders such as anxiety and depression into primary care. However, due to the tremendous burden on primary healthcare nurses caring for individuals with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, it has not been possible to expand additional services to cover MNS disorders.

Kakooza-Mwesige remarked that integrating MNS with HIV care is critical to the safety and well-being of the patient. Providing HIV treatment can reduce the prevalence of comorbid MNS disorders. Katabira stressed that the HIV/AIDS resources need to be leveraged to improve all associated symptoms, including MNS disorders. Using these resources will allow improved models of care to be developed, which in turn could be applied to other MNS patients, thus improving care for all individuals with MNS disorders.

An example of this is how MNS was integrated into the “Village Health Team” in Uganda. These are members of the community who are selected by the community to take care of general health issues, including treating minor ailments, routine immunization, HIV/AIDS counseling and testing, and informing the community about services available at health units. Through the Ugandan system of training, mental health has been integrated into that Village Health Team manual so the Village Health workers recognize mental health illness. Ultimately, the hope is to change the perception of mental health illness in local Ugandan communities, which will be strengthened through collaborations

|

BOX 2-1 Advantages of Community-Based Care

|

with traditional and complementary healers as guided by the Ugandan public–private partnership policy. Some Village Health Teams have better results than others, mainly due to a more advanced system of referring patients.

Kakooza-Mweisge believed that the need for integrated care was clear, especially given the complexity of the drug regimens to which patients with multiple issues must adhere. Because many HIV-related MNS disorders are related to seizures, often patients are put on antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) and anticonvulsants. However, due to adverse interactions with ARVs and the common anticonvulsant drugs phenobarbitone, carbamazepine, and phenytoin, these medications should not be given together. Furthermore, ritonavir and nelfinavir use may raise serum levels of these anticonvulsants into toxic ranges. This creates a dilemma whereby the drugs that are beneficial to patients like Phenobarbitone, at less than 5 cents a dose, could harm the patient on HIV drugs. Kakooza-Mweisge asked the audience, “What do we do?” Patients are not able to afford the newer generation of antiepileptic drugs on the market, which are much more expensive than Phenobarbitone. Plus, no guidelines exist on indications of protocols for treatment of new-onset seizures for HIV infection. Adherence to the complex regimens of antiepileptic drugs, antiretroviral drugs, and opportunistic infection prophylaxis is a big issue. Now, with the increased number of patients taking ARVs, HIV patients have increased rates of survival. This means care providers need to select successive new antiretroviral regimens and continuously monitor patients, especially those who are on antiepileptic drugs or anticonvulsants for short- and long-term toxicities. But the question is whether the developing world has the available resources to do so.

Task Shifting

The key to success in a community-based model—or indeed any model in which general healthcare personnel are retrained to provide specialist functions—is task shifting, explained Patel (see examples in Box 2-2). Task shifting simply means that specific medical tasks can be transferred from specialists to newly trained individuals. Ultimately, setting up programs that support task shifting is one part of a coordinated strategy to increase the full spectrum of MNS providers: clinical psychologists and neurologists, clinical social workers, certified counselors, nurses and clinical officers. Often because of the limited tasks and scope of work, less training is required, significantly lowering

the cost to the health system and allowing a more efficient use of available human resources. For example, Patel discussed the results of a recent study published in Lancet on treating postpartum depression in mothers in rural Pakistan (Rahman et al., 2008). The study trained village women with little education to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy using training materials based entirely on cartoons and pictures. The training was given over a 2-day period, and the women treated were followed for 12 months. The study’s authors were able to demonstrate that not only were there benefits to the mothers, but also to their babies. The babies had high rates of immunization coverage, as well as low rates of pneumonia, diarrhea, and other infections compared to those whose mothers did not receive the treatment, highlighting the importance of this program not only to the mothers but also their children.

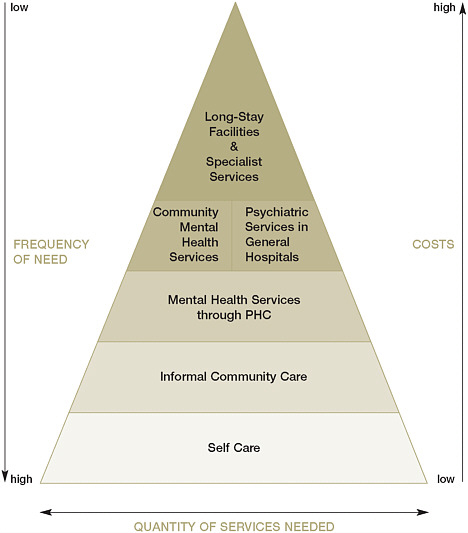

This type of evidence does not suggest that task shifting and an emphasis on community health workers translates into a healthcare system that no longer needs specialists. In fact, all of the examples presented at the workshop involved a wide range of specialists, although their roles differed from one example to the next. Rather than treating a patient in one-on-one settings, they were instead the leaders of a program, developing the treatments, training, and developing materials the community health workers would use. The specialists had roles such as advocating for the patients, supervising the health workers, and receiving referrals from the community facilities (Figure 2-2). Patel sees this as a logical evolution of the specialists’ role in a resource-constrained environment. “The role of specialists need[s] to be completely refashioned and redefined in a great new world,” he suggests. “Rather than spending all our time seeing patients … really the role of a specialist needs to move from physician to public health practitioner.”

David Ndetei, director of the African Mental Health Foundation, suggested that the traditional healers may be in just the right position to help with task shifting. As noted in the section on traditional healers, they are already a trusted voice in the local community, are numerous and, according to his case study, are willing to learn about more ways to help treat their patients, whether based on Western medicine or not.

But task shifting is not without its challenges. “One of the things that we have realized is that it is one thing to train somebody for a week and then send them out to provide quality mental health services,” said Christine Ntulo of Basic Needs UK. “But there are still issues around proper coaching and mentoring. If we do not have those structures in place, we do more damage to the patient than good.” As an example, she listed the case study of training healthcare workers in one district.

Trainees were supplied with medications and were evaluated every 3 months. One trainee thought that because three different medicines for headaches could be used interchangeably (panadol, cetamol, and rapidol), it meant that chlorpromazine could be substituted for carbamazepine because they were out of it and they both ended with the letters “ine.” As a result, the frequency of the in-person evaluations were increased to

FIGURE 2-2 The WHO’s optimum mix of mental health services.

SOURCE: WHO, 2010.

monthly from quarterly. Task shifting also requires additional personnel. Makerere University’s Katabira noted that the problem with task shifting is that to maintain quality, a dedicated policy for supervision is needed. This requires increases in the number of specialists, doctors, and nurses to ensure sufficient capacity and supervision for the new patients achieving care. In addition, there needs to be formalized periodic continuing education programs.

With the wide use of task shifting throughout the healthcare system, Gary Belkin, associate professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine, noted that further research needs to be done on the effects of task shifting, including the following:

-

What is the true quality of care that is provided in task-shifted environments?

-

What decision support systems are needed?

-

What kind of feedback system needs to be in place to make the treatment interventions work?

|

BOX 2-2 Task Shifting at Work: Example from Kenya and Rwanda Kenya When Kenya developed its National Health Sector Strategic Plan, which ran from 2005 until 2010, a key feature of the plan was to decentralize mental health, neurological, and substance use (MNS) disorders care, moving it from specialized hospitals to primary care facilities. As the Kenyan Ministry of Health worked to implement the plan, it found it did not have enough skilled health workers to treat the diseases it was seeing. It was decided to use existing health workers and train them to increase their skills so they could deal with the MNS disorders they were seeing in the field. To retrain the clinical officers and nurses in the facilities, a partnership was forged between the Ministry of Health, the Kenya Psychiatric Association, the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre and Section of Mental Health Policy, and the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings College in London, among others. The community health workers, along with the district mental health workers who supervise them, were trained in the knowledge, skills, and competencies involving basic mental health issues, and they were also trained on how these issues contribute to both a person’s physical health and social outcomes. Part of their training included understanding the relationship between mental health and areas such as child health, reproductive health, malaria, HIV, education, and economics. Mental and neurological disorder assessment, diagnosis, and treatment were also taught. “We wanted to sensitize them,” said David Kiima, director of mental health for Kenya’s Ministry of Health. “They have a responsibility to |

|

implement the community health strategy and to understand the mental health policy and legislation.” To create a sustainable system, the training process began with facilitators, senior staff, and other trainers in 2005. From 2006 to 2009, roughly 25 people attended an intensive one-week training session, each and every week, with a total of approximately 1,500 workers trained to date. The process has not been without challenges, but significant progress has been made. Rwanda Arguing for the mental health benefits of a broad commitment to general primary health care, Paul Farmer, cofounder of Partners in Health and professor of social medicine in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard University Medical School, spoke about the 1998 HIV Equity Initiative in Haiti that used community health workers to provide care in their communities. Global Fund money was used to not only strengthen HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, but also to strengthen primary health care in general in the public sector. The result was an increase in primary care visits and HIV detection rates, and an increase in prenatal care visits and rates of vaccine administration. This same program was brought to Rwanda, and since 2005 it has scaled up in three of four districts that have no district hospital. The program is showing results similar to what occurred in Haiti, with improved primary care, including high compliance with HIV/AIDS antiviral protocols. Consistent contact with community health workers seems to be key. “Strengthening primary health care—training people to do this in their home visits—is the highest standard of care in chronic disease management,” Farmer said. “This frees up doctors and nurses to do the things they could do best. And I would argue that the same holds true for mental health illness.” |

Traditional Healers

Workshop participants noted that, while there is a dearth of specialists trained in Western medicine, there are a significant number of traditional healers to whom individuals routinely turn for care. Furthermore, individuals with MNS disorders in SSA often seek care from traditional healers before seeking out Western-trained doctors.

Some of the most lively discussions during the workshop revolved around the role of traditional healers in providing care for MNS disorders. Unlike Western medicine, which is based on empirical data on the effectiveness of treatments, the effectiveness of traditional healers is not known and the approaches are not standardized, said Florence Baingana, a research fellow at Makerere University’s School of Public Health. “[Traditional medicine] may be providing a benefit,” but there

have not been any comprehensive studies, therefore we don’t know the effectiveness and potential benefit to the patient.

However, some workshop participants noted that evidence can be quantitative as well as qualitative. “Certain things can only be studied by qualitative evidence, and it is not necessarily less important or less valuable than quantitative evidence,” said Roy Baskind of the Division of Neurology in the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto. “Traditional healers are very difficult to study with quantitative means, and the lack of evidence is not evidence of the lack of efficacy.” Baskind and others reiterated that this did not suggest data should not be collected, but rather, that a broader understanding of the role of traditional healers must be taken.

Baskind reported the case of a child with epilepsy to demonstrate that though the traditional healers in the case did not “cure” the child, they did perform important services. First was social intervention: In this case, the child and all family possessions had been taken from its mother by the paternal grandparents after the death of the father. The first traditional healer said the seizures were caused by the angry spirit of the father and that the child and all of the family possessions should be returned to the mother to appease the spirit. Second was stigma reduction: Because many believe seizures are contagious, and refrain from touching an affected person or even visiting the house of an affected person, by performing a cleansing ceremony, the traditional healer allowed the family and village to believe they were protected from catching the seizures, reducing the stigma.

Workshop participants identified other strengths and weaknesses that traditional healers brought to caring for sufferers of MNS disorders. For example, strengths of traditional healers include the following:

-

Traditional healers live in the community and know the people they are treating and their families and their histories, and they are often very good at solving family, social, and neighborhood problems.

-

Traditional healers are more accessible to a community and are local. In addition, they often barter instead of requiring money, lowering the barrier to care.

-

Traditional healers often spend substantial time with their patients and engage with more of the family members than is possible in a clinic.

-

Traditional healers are already established as accepted and respected parts of their communities.

However, potential weaknesses do exist. For example, traditional healers may not have appropriate treatments for all diseases. This is particularly the case for neurological diseases and disorders such as psychosis or epilepsy. In addition, there is no standardization of traditional remedies and treatments among traditional healers, or even a definition of what a traditional healer is, how they are trained, or who they are.

While understanding these strengths and weaknesses, Baskind commented, “It is important to note that patients do not take sides. If you ask someone with epilepsy in rural Africa, which do they prefer? They don’t care, they want treatment that is available, they want their needs met—be it stopping the seizures or [curing] depression—but also [they want] an explanation of why they have it. They want to be able to believe in the treatment; it needs some legitimacy and traditional healers have legitimacy because they are traditional.”

Makerere University’s Seggane Musisi noted that there was recent research evidence suggesting that, in MNS care, those patients who use both Western and traditional medicine did better than those who used either method alone. Treating traditional healers with respect is critical when approaching them for collaboration. “As long as you go to a traditional healer with a spirit of partnership, then it works,” said Ntulo of Basic Needs UK. “That’s how—where we work in rural Nairobi and in Ghana—we have been able to actually break through the barriers of traditional medicine. They have been invited to the discussions as equals who have their own area of specialty. And when that happens, then they are able to open up and share.”

Integrating Traditional and Western Medicine

Many workshop participants believed that collaboration between Western and traditional medicine is the most practical way forward for most sub-Saharan communities. It will be important to develop policies that formally integrate traditional healers into the health system. However, the absence of understanding between the two communities complicates collaboration and a coordinated approach for health care. “It is difficult to integrate or collaborate with people when you don’t know the essentials of what they provide, especially where you were talking about evidence-based service,” says University of Ibadan’s Oye Gureje.

Although evaluating the role of traditional healers is difficult, it is possible to divide traditional healing practices into beneficial, benign, and harmful practices.

In Uganda, the policy of the Ministry of Health is to attempt to formally work with traditional healers. Their experience has shown that by working with them, traditional healers become sensitized to the unique mental health needs of their patients and many have started referring patients to the Western health centers for treatment. Patients who want to see traditional healers may, but they are encouraged to continue to keep taking their medications and return to the health centers at any time. Critically, patients being seen in a collaborative care system are also cautioned not to take herbal remedies in addition to the Western medications. But rather than a blanket prohibition, Uganda has taken the issue of traditional herbal medicine seriously, establishing a national chemotherapeutic laboratory that works with traditional healers to analyze their medications. The compounds can be analyzed to look at the active ingredients, check for efficacy, refine them, and even package and market them while retaining the traditional healer’s intellectual property.

Musisi emphasized the need to train, certify, register, license, integrate, and supervise traditional health practitioners for mental health care in primary health care and establish a formal health care category of Traditional Mental Attendants akin to the Traditional Birth Attendants of midwifery (Okello, et al. 2006). Categorizing the practice of traditional healers into categories—beneficial practices, innocent practices, and dangerous practices—would assist in encouraging beneficial practices while regulating and discouraging dangerous practices. It would further help in formalizing education practices and incorporating them into the health system.

Access to Care Through Technological Advances

Technology, specifically mobile technology, offers the greatest potential for improving care in SSA. It holds tremendous value in both task shifting and bringing training and treatments to rural communities. Like the Mobile Health initiative, described below, that provides decision-tree and treatment support to practitioners in the field, there are many ways to use technology to create virtual specialists. Simply delivering the Internet and computer-based technology to the village level will do a great deal to improve the availability of quality information.

Frank Njenga, president of the African Association of Psychiatrists and Allied Professions, noted, “Everybody now has broadband connectivity. We are already using it at the district level. Imagine how beautiful it would be to teach cognitive behavioral therapy techniques to people at the [village] level using this broadband connectivity.”

The goal is to push technology—and, more importantly, connectivity—as far into the field as possible. “We are already using solar-powered computers to download information not at the district level, but at the village.” Indeed, Njenga believes technology may be one of the continent’s best hopes in advancing general health. “We in Kenya have decided that at the end of next year we will have a million computers across the country.” This is a goal for 2010.

Julia Royall, chief of international programs for the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM), provided background on the readily accessible information through sites provided by the NLM. For example, more than 16 million citations are available through Medline. MedlinePlus contains 700 health topics, including interactive tutorials, surgical videos, and many other sources of information. These are peer-reviewed, evidence-based resources that are free to anyone with Internet access (NLM, 2010). But health workers need to know that the resources are available.

Mobile Health Technologies

One tool developed for these health workers are applications and training modules that can be used on a mobile phone, providing decision trees and checklists, called Mobile Health. “A decision tree not only guides the health workers specifically to actions that they would perform, but also to specific information that needs to be imparted during the visit,” explained Belkin. It also identifies key triggers when the patient needs to be referred up to the next level of care. Currently this type of tool is used for prenatal and postpartum care of mothers and newborns and with children.

The current plan is to expand existing tools and introduce a mental health component into the stream of work. “We are going to develop the same sort of logic tools and decision support tools for depression,” said Belkin. “These tools are part of the intervention and are also part of the quality and management processes at the same time.” Mobile tools can be developed that have the ability to create summary and tracking reports for the supervisors and the clinical staff, allowing supervision not only of the care, but also of the system that delivers that care.

But for the moment, this remains just a plan. Creating the expert system needed to treat MNS disorders, such as depression and substance use disorders, requires a substantial investment of time and money. How to implement treatments and how to coordinate processes for those treatments have yet to be determined. “These components have to be scalable as well, and I will tell [you] that those challenges are a global challenge. It is a challenge in eastern New York, and it is a challenge in East Africa,” said Belkin. “You have a working model of how that is going to be delivered, of how the quality is going to be overseen. You have crossed out that whole package together—training and process—and all those components [have to be] scalable,” said Belkin. To facilitate this, Belkin said, “The village clusters in each country are directly linked into the district and national policy-making process.”

The idea of mobile technologies could, theoretically, extend to providing patients with up-to-date information pertaining to alerts such as hospital hours or availability of new supplies and medicine. This would help address the issue of patients traveling for hours to a clinic only to find that it is closed or the medications they need are not there.

Financing MNS Care in Sub-Saharan Africa

Financing delivery of care to individuals with MNS disorders presents another challenge to the delivery of quality care. This challenge is even greater in SSA due to competing priorities of other disorders such as HIV/AIDS and malaria, commented Hyman from Harvard University. However, as discussed earlier, treatment of MNS disorders should be part of a much larger integrated health network that leverages the strengths of existing infrastructure and resources.

The Millennium Development Village Project

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals consist of eight goals to end extreme poverty by 2015 (United Nations, 2009). The eight areas for development include an end to poverty and hunger, universal education, gender equality, child health, maternal health, combating HIV/AIDS, environmental sustainability, and global partnership. The Millennium Development Village Project is working to show how these development goals can be met and includes a holistic approach to health care. Belkin from New York University presented to the workshop how

the project’s healthcare approach works and suggested how mental health could be integrated into primary care.

To meet the healthcare targets of the Millennium Development Goals, the project assumes that approximately $40 to $50 per capita must be spent on health care. Belkin explained that this assumption comes from what is needed, not necessarily what is actually happening. “This is an important thing to specify because the model that we demonstrate is in many ways locally not affordable,” he conceded. “But the logic of this approach is to think about the fundamental component needs for one to be effective both in terms of the process and content, in the package as well as the delivery. This makes the point that no health system that operates on $10 per capita can be successful … you have to understand what the resource needs are.” The project covers 12 village clusters across 10 countries in SSA. Each cluster consists of 40,000 to 60,000 people. In each cluster, there is 1 clinic with a staff of 2 nurses and approximately 40 health workers. The health workers service 150 to 250 families each by going out into the communities and making house calls (United Nations, 2006).

The structure of the project is important—village clusters are directly linked to the district hospitals, but the community health workers walking from home to home are the ones who truly bring patients into the healthcare system. These workers participate in approximately 4 weeks of training, exams, and assessments, and they are then monitored and supported once they are in the field. Continuing support for these workers is a critical part of the project.

Collective Bargaining for Medications

Many MNS disorders are relatively easy to control with the proper medications. However, ensuring that medications are consistently available in the appropriate therapeutic dose is difficult to do in many areas of Africa.

Paul Farmer, cofounder of Partners in Health and professor of social medicine at the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard University Medical School, presented data from Partners in Health on the cost of ARVs that serve as an example of the value of collaborations. The wholesale cost for a common three-drug ARV regimen is around $10,000 per patient per year in the United States. However, through the use of collective bargaining, Partners in Health was able to procure generic drugs for $600 or $700, depending on the specific drugs needed, while the International Dispensary Association—