5

Research and Commercialization Infrastructure

Innovation depends on a research infrastructure that generates and validates new ideas and a commercialization capability to take the creations of the R&D process and transform them into commercially successful products and services that generate a return on investment. In a session devoted to these conditions for innovation, moderator J. Thomas Ratchford of George Mason University introduced presentations on Chinese and Indian government plans for science and technology development by Mu Rongping, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Venkatesh Aiyagari of the Indian Department of Science and Technology.

In describing the context of the discussion, Ratchford commented that globalization, having been enabled by science and technology, has in turn changed the practice of science and technology around the world, including in China and India. In contrast with 20 years ago, both countries now have large, growing economies. China has a gross domestic product (GDP) of between $2.5 trillion and $7-8 trillion, depending on whether it is estimated by the MER or PPP method, and India’s is between $800 billion and $4 trillion. By comparison, the United States has a GDP of $13 trillion. China invests about 1.3 percent of its GDP in research and development, with about 67 percent coming from private investment, not far from the median for developed economies. India, by contrast, spends only about one-third as much—0.4 percent of its GDP—on R&D, with only 20 percent coming from the private sector.

Besides capital, Ratchford added, successful innovation also requires highly skilled technologists and managers. In this regard, both China and India are increasingly well-endowed with hundreds of thousands of well-trained people employed in R&D. China may lead India to some degree in R&D human capital, but both countries unquestionably have access to scientists and engineers trained at some of the best universities in the world and thus have resources for productive, internationally competitive research and development.

CHINA’S NATIONAL INNOVATION STRATEGY

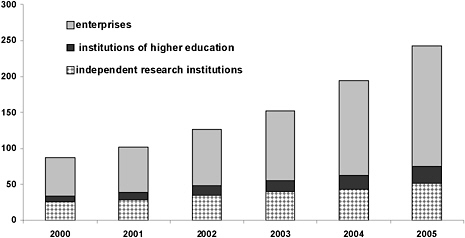

Mu Rongping, addressed China’s changing national innovation strategy. China’s economic growth has been caused more by the low cost of labor and high investment than by innovation, he observed. China has insufficient investment in innovation, an unbalanced allocation of innovation resources, and too little R&D (Figure 8). That realization is now spurring a new development philosophy aimed at

-

closing the large gap between the R&D capacity of leading universities and business enterprises;

-

raising patent productivity in enterprises;

-

raising research productivity as measured by publications and citations; and

-

strengthening linkages among research institutions.

The central government’s policies for building innovation capacity include

-

increasing expenditure on science and technology to spur and maintain growth;

-

instituting tax incentives in the form of deductions for technological development in enterprises;

-

focusing government procurement on purchasing new products;

FIGURE 8 R&D expenditure in China (billion RMB Yuan) SOURCE: Source: Adapted from S&T Statistics Data Book (2001-2006) Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology

-

providing direct financial support;

-

encouraging adoption of imported, assimilated technologies; and

-

enhancing protection of intellectual property rights with higher standards, faster processing of applications, better trained and qualified reviewers, and facilitation of the flow of patented technology to enterprises.

In addition to national government initiatives, localities have instituted incentives for science and technology investment, with the result that S&T expenditures have increased dramatically in most provinces, even since 2006. Nevertheless, a great many enterprises have yet to benefit from national and regional innovation policies, either because of a lack of awareness or because the rules for taking advantage of the incentives are complicated.

China’s goal of becoming an innovation-driven country is highly ambitious. It depends on many factors including an innovation-friendly internal culture and effective foreign investment. Fields in which it is believed China can make a substantial unique contribution to global science and technology include biology and Chinese medicine, nanotechnology, space science and technology, and energy.

INDIA’S RESEARCH INFRASTRUCTURE

Venkatesh Aiyagari described India’s changing research infrastructure. The driving factors in scientific innovation are investigators’ passion for a discipline, for crossing intellectual boundaries, and for meeting society’s needs. Early pioneers in Indian innovation focused on improvements in agricultural and dairy production, led by the TATA Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), and in space and satellite technology, led by the country’s defense laboratories and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

Today, recognizing that Chinese investment in R&D far outpaces India’s, the country aims for faster and more inclusive growth, according

to Aiyagari. Government plans focus on

-

developing talent by inspiring students to pursue careers in science and technology;

-

fostering creativity rather than rote learning; and

-

ensuring that scientific and technical careers are secure and attractive.

In the 11th national plan covering a five-year period that commenced in 2007, India is endeavoring to triple investment in basic research while quadrupling overall investment in science. Earlier the government created the Fund for Improvement of S&T Infrastructure in Universities and Higher Educational Institutions (FIST), launched a program for research in nanoscale science and technology, and began to expand the network of Indian Institutes for Science and Research (IISERs) as well as the number of Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). Although in its early stages, the nanotechnology initiative, while focusing on basic research, has involved industry in eleven centers of excellence.

In addition to public investment, the Indian government aspires to encourage growth in private investment, including by small and medium-size enterprises. The New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative, for example, includes a small business initiative in biotechnology with medical, agricultural, food, industrial, and environmental applications. The premise is that technology producers and users need to collaborate for innovation to address market needs and opportunities. Nevertheless, overall, Indian efforts to boost private investment have not been highly effective.

PANEL DISCUSSION

These presentations on Chinese and Indian S&T policies were followed by a panel discussion led by Denis Simon of the Levin Graduate Institute of the State University of New York. Simon observed that there is a wide divergence in views of Chinese and Indian progress among both western and native experts. Some emphasize the resurgence of activity and level of commitment and claim that China and India are making rapid progress in spurring innovation. Others draw sharp contrasts between the two countries, and still others focus on the distance China and India have to go to match western, especially U.S., standards. He asked the members of the panel to characterize their own views.

Defining innovation as the ability to develop and successfully market new products and services in the global economy, Carl Dahlman, Georgetown University professor and former World Bank official, observed that a variety of institutional and policy changes, such as liberalized trade policies, contribute to that capacity. Other conditions are holding each of the countries back. In India, he said, weaknesses in the educational system constrain the growth of the country’s talent pool. He judged human resources in the information and computer technology field to be “quite shallow.” Both countries have a long way to go, in Dahlman’s view, before they become technology superpowers.

Harkesh Mittal, from India’s Department of Science and Technology, highlighted India’s diversity in climate, language, and culture, making it “a nation of nations.” A tension exists between the stability that is politically desirable and the disturbance required for change and growth. In Mittal’s view, at least for the time being, India, has achieved an equilibrium that is contributing to economic momentum. He cited the example of an Indian nanoscientist participant in the Global Innovation Challenge held in Berkeley, California. He brought artificial flowers whose fragrances were so real that he was detained temporarily by U.S. Customs for bringing in banned botanical samples. Another example he cited was an Indian firm with a new technology for foiling car thefts. Such cases, according to Mittal, are grounds for great optimism about India’s innovation climate.

Lan Xue of Tsinghua University claimed that over the past 10-12 years, China has established the infrastructure necessary for sustained, technology-based growth. The challenge for China is to make the infrastructure work successfully with industry. Other challenges include a wider distribution of

benefits from technology and harnessing science and technology to support efforts to address China’s enormous environmental problems.

Adam Segal from the Council on Foreign Relations posed the question, “What differentiates young innovators in China?” The first wave, including Lenovo, used a model of getting into new market space. The second generation of innovators is tapping global networks for a confluence of government funding and returning expatriate talent. State-run enterprises do not have this synergy.

Richard Forcier of Hewlett-Packard noted a disparity between China’s and India’s energy infrastructure. China is pursuing a huge growth in power generation, planning to build 500 coal-fired power plants in the next decade, at the rate of almost one a week, while India’s power sector is slowing. Companies in China are building more innovation capacity to attract more experienced managers.

To grow R&D capacity in China, Xue observed that research universities are seeking to work with multinational companies. A key feature of the Indian landscape, Mittal noted, is the growth of public technology incubators, a network of centers where enterprises can tap technical and managerial expertise in a single location. The National Science and Technology Entrepreneurship Development Board (NSTEDB), a division of the Department of Science and Technology, is spearheading the creation of incubators in universities and other institutions. Activities are ramping up, but not all entrepreneurs are taking advantage of their services. Nevertheless, the panel agreed that both countries are doing a great deal to stimulate innovation from the supply side.

In both cases a critical driver of innovation is the country’s diaspora, linking the research and commercial enterprise to the global system. Even remotely, Chinese and Indian researchers and business entrepreneurs living abroad provide sources of investment and opportunities for market development. But increasingly, members of the diasporas are returning home to lead research institutions and enterprises, and they bring with them needed managerial expertise as well as links to foreign laboratories and firms with superior capabilities. Equally important, according to Lan Xue, is the role of foreign direct investment in fostering knowledge spillovers, not only to local firms but also to research institutions, including universities, with which the multinationals are forging more and more links.

Foreign influences are helping in both countries to create a culture of creativity, but progress is not necessarily rapid. Hewlett Packard’s Forcier remarked that he is impressed by the talent and energy of the local Indian workforce but finds many reluctant to take a great deal of initiative. Mentoring the local staff often involves encouraging employees to raise new ideas in corporate planning processes and not hold back. Lan Xue agreed that in China the tendency is to duplicate previous innovation successes rather than create new products. There are, for example, ten to fifteen Chinese versions of MySpace and Facebook.

Simon questioned the panel about the distribution of innovation-related investment among regions in China and India. Are significant investments being made outside Shanghai and Bangalore? Panel members agreed that there is wide variation in both countries, with some areas showing considerable interest and others relatively little. In India, according to Mittal, most activity remains in the regional hubs, but it is starting to trickle beyond those cities, in directions determined by investment and market contacts. In China, government incentives have led to greater activity in certain western provinces such as Xian, but a large majority of the R&D investment is still concentrated on the East Coast. Less well developed regions tend to follow the central government’s lead on innovation policy and to depend on central government resources. Wealthier provinces like Hangzhou, on the other hand, have taken the lead on innovation without depending on national initiatives.

Finally, Simon probed the public-private sector distribution of R&D. Lan Xue observed that in China there has been a dramatic shift in R&D performance in recent years. In 2006, more than 70 percent of research funds were spent by industry, whereas 20 years ago public research institutions accounted for almost that proportion, about 60 percent. On the other hand, multinational corporations account for a large

share of the growth – over 70 percent of industrial R&D spending in Shanghai and roughly 30 percent nationwide. Indigenous enterprises also lag in taking advantage of the strengthening of intellectual property rights in recent years. India has yet to achieve a distribution of R&D activity between public and private sectors comparable to that of other industrial countries.