Appendix D

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Food Defense Program1

This appendix describes the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) food defense program from 2001 to the present. It places bioterrorism within the broader context of terrorism and the associated legal and organizational framework. It also describes the formal and informal cooperation between the FDA and other groups and organizations involved in food defense, including the creation of a government–industry partnership. Outcomes of this partnership were the development of a risk vulnerability assessment model and its application in the food industry. The appendix also reviews the issues that arise in, and approaches to, acquiring and sharing food defense data. Examples of the capacity of the FDA to respond to emergencies are provided as well. Further, the appendix describes how the FDA’s 2007 Food Protection Plan (FPP) includes food defense in its goals. The progress made to date with regard to management of food defense is described, and gaps are identified. The appendix concludes with a summary and a list of opportunities for improvement in maximizing the outcomes of the industry–government partnership, developing tools for prioritization of risks, maintaining resources, and enacting needed legislation.

This appendix was written based on information gathered from interviews with representatives of federal and state government, academia, and industry; public documents from both government and industry sources; and the author’s experience and expertise in food defense as former Deputy

Director of the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s (CFSAN’s) Office of Food Safety, Defense, and Outreach. Where comprehensive source materials were unavailable, the discussion relies on anecdotal information and inferences from program directives.

BUILDING A FOOD DEFENSE PROGRAM

“Food defense” is the collective term used by the FDA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and others to describe activities associated with protecting the nation’s food supply from deliberate acts of contamination. Shortly after September 11, 2001, the FDA and other federal agencies began developing a new program, building on a program initiated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to protect the nation’s food supply from terrorist attacks. The FDA focused its efforts on targeted industry guidance and outreach, inspections, research (e.g., methods development and validation, characteristics and behavior of agents in foods, pathogenicity/toxicity in foods), and mitigation strategies to reduce potential risks in the food supply. Numerous organizations, public and private, have played a role in the FDA’s food defense program to date (see Annex Table D-1).

The FDA used operational risk management (ORM) as a tool to identify food defense priorities. ORM is a management tool used by the U.S. Departments of Defense (DoD) and Transportation to identify risks and reduce them to an appropriate level, ensuring that benefits will outweigh any risks. It is an analytical tool whereby severity and probability (accessibility) of risk are measured qualitatively and assigned a rating—high, medium, or low (see Table D-1).

A CFSAN team of scientific and food production experts was charged with testing the tool on a list of threat agents, starting with the list of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and expanded to other known or potential threat agents, in combination with a list of FDA-regulated foods. The class groupings were, for example, heat-labile bacterial toxins, heat-stable bacterial toxins, and spore-forming bacteria. The agents (surrogates) were also assessed on their accessibility, public health impact (morbidity and mortality), toxicity/pathogenicity, dose required to cause intended outcome, agent–food compatibility, ability to withstand processing, and changes to sensory attributes of food. (The resulting list of prioritized agent–food combinations is classified and unavailable for this discussion.) This risk assessment effort, early in the evolution of the food defense program, was crucial to identifying a finite list of agent–food combinations for further investigation and helped in understanding the potential hazards. Equipped with this risk assessment tool, the FDA focused

TABLE D-1 Risk Assessment Tool: Operational Risk Management

its resources on identifying the greatest vulnerabilities and opportunities for reducing risk in the food supply.

The FDA, with the voluntary participation of food industry trade associations, subsequently conducted a series of ORM exercises. With the information thus gathered, physical security, employee, management, and quality assurance practices were identified and published in a series of Food Security Preventive Measures Guidance documents for Industry for Food Producers, Processors, and Transporters; Dairy Farms, Bulk Milk Transporters, Bulk Milk Transfer Stations, and Fluid Milk Processors; Retail Food Stores and Food Service Establishments; Importers and Filers; and Cosmetic Processors and Transporters. In turn, many food industry trade associations and food producers updated their facility quality assurance or crisis management plans to incorporate these features.

In an effort to further assist the industry, the outreach effort was broad in scope, encompassing all FDA-regulated food producers from farm to table. Equally important was training the FDA’s own investigators and field scientists in this new threat—intentional contamination of the food supply. Training materials, face-to-face sessions, and web-based courses were developed to educate the industry and the FDA’s food safety experts and to share this information with their state and local counterparts.

At the outset of this new food defense program, the FDA and its food safety/defense counterparts at CDC, USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), DoD/Army Veterinary Corps, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) were embarking on different paths, many using established food safety risk assessment methodologies, to protect the food supply. With the FDA’s novel approach, it was prudent to ensure rigor and scientific soundness, and the risk-ranking list of agent–food combinations and the ORM tool were subjected to peer review through a contract with the Institute of Food Technologists. When the risk-ranking list and the ORM tool passed this review, the FDA further augmented its outreach to its federal and state partners and enhanced training and outreach efforts with the food industry, given their mutual responsibilities for dealing with potential food safety events.

HOMELAND SECURITY AND FOOD DEFENSE

In 2003, with the formation of DHS, emphasis was placed on infrastructure protection, a National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP), a National Response Plan (NRP), and the overarching mandate to engage public and private entities in homeland security as described in various Homeland Security Presidential Directives (HSPDs). The FDA and its federal partners were challenged not only to build a working relationship with a new entity—DHS—but also, in an expedited manner, to build a food and agriculture public–private partnership; fully develop and implement a voluntary national defense program to protect the food supply from intentional contamination; update all current emergency response procedures, including those involving the new DHS; and train and educate their staff and regulated industries in this new program.

Adding to the FDA’s tasks, Congress passed the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (Bioterrorism Act of 2002),2 which required the agency to expedite rule making for 4 new authorities and implement those authorities within a time frame of 18 months. The new authorities were registration of domestic and foreign food producers, manufactures, and distributors; prior notice of imported food shipments; record-keeping requirements; and administrative detention (see Table D-2). Given the timetable for publication and implementation of the draft rules, the FDA faced a monumental outreach and education effort in providing the necessary materials and details in simple language to enable all to comply. During the 2003–2005 time frame, the FDA/CFSAN was engaged in activities to comply with the HSPDs and congressional

TABLE D-2 Provisions of the Bioterrorism Act of 2002 Relating to the U.S. Food and Drug Adminisration (FDA)

|

Registration of food facilities |

Requires food manufactures, processors, holders, and distributors to register each facility, not company, with the FDA. The registration coverage is limited and does not encompass farm to table, specifically excluding farms and retail establishments. |

|

Prior notice of imported food shipments |

The FDA must receive and confirm a prior notice |

|

|

|

|

Record keeping |

Requires each domestic food manufacturer, processor, holder, or distributor food/feed facility to retain records of incoming ingredients and supplies and of outgoing products. |

|

Administrative detention |

Gives the FDA domestic embargo authority, whereby suspect or contaminated food in commercial channels can be stopped until judicial action is taken to seize and/or destroy it. |

legislative requirements, and to educate and communicate with industry, its own staff, and state, local, and foreign counterparts.

The FDA’s outreach efforts leveraged all media opportunities to educate industry and state and foreign governments in the new regulations and food defense program. The FDA teamed with USDA to develop joint food defense training materials and promoted their adoption by industry and the states. The latter effort was focused on generating awareness of the new food defense program and training food safety professionals to be the eyes and ears for potential threats to the food supply. Awareness training included how to identify potentially intentional contamination and whom to notify, as well as information about the implications of a terrorist attack on the U.S. food supply (including production agriculture). The training was offered both as a web-based course (FDA, 2009a) and in face-to-face sessions. Later, as part of this training, the FDA and USDA developed simplified tools, such as ALERT (FDA, 2009b), intended to raise awareness at all levels of food production, and FIRST (FDA, 2009c), designed for use by food industry managers to educate front-line workers from farm to table.

ESTABLISHMENT OF A PARTNERSHIP: THE FOOD AND AGRICULTURE SECTOR

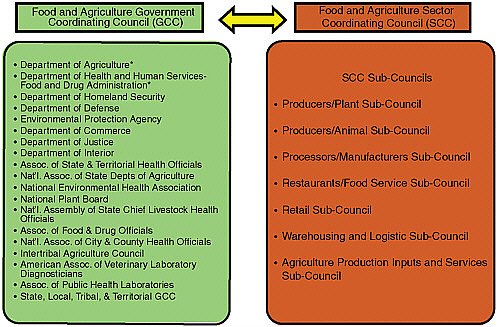

By Presidential Directive, FDA/USDA and the newly formed DHS were required to establish a sector organization, that is, a partnership with all relevant federal, state, local, and industry counterparts. Although there were existing models for such a partnership in other areas, none were suitable given the diversity, scope, and magnitude of the food and agriculture sector. The FDA/USDA/DHS, with industry, formulated a governing model and operating procedures for the new Food and Agriculture Sector, with the goal of identifying and protecting critical infrastructure assets and establishing a two-way communication and analysis system to inform and notify members and analyze critical food defense information. The Food and Agriculture Sector partnership comprises two governing councils: (1) the Government Coordinating Council (GCC) and (2) the Sector Coordinating Council (SCC) (representing industry). The membership of each council was expanded over time. In addition, seven subcouncils were created under the SCC so that each industry segment—harvest, production,

FIGURE D-1 Participant organizations of the Food and Agriculture Government Coordinating Council and Sector Coordinating Council.

NOTE: In the summer of 2009, the subcouncils integrated into one large council. *Sector specific agencies for the Food and Agriculture Sector.

retail, distribution, and supply—would have a voice (see Figure D-1), and they were dissolved later in 2009. Since its inception, the program has relied on voluntary participation and engagement by the states and industry.

The GCC was established to enable interagency coordination of food and agriculture security strategies and activities, policy, and communication across government and between the government and each sector, with the goal of developing consensus approaches to the protection of critical infrastructure/key resources. DHS, FSIS, and the FDA co-chaired the GCC, each serving as its lead for 12 months on a rotating basis. The SCC is self-organized, self-run, and self-governed. It is composed of members that serve as the GCC’s point of contact for each industry sector (i.e., plant and animal producers, manufacturers, restaurants, retail, warehouses, and agricultural production) for developing and coordinating a wide range of infrastructure protection activities and issues (e.g., research and development, outreach, information sharing, vulnerability assessments/prioritization, shielding, and recovery).

Regular conference calls and quarterly meetings of the GCC and SCC addressed organizational issues, communication efforts, emergency operations, training and planning, identification of annual priorities, and participation in such activities as emergency response exercises, the development of risk communication templates, and a Strategic Partnership Program Agroterrorism (SPPA) initiative, all in an effort to contribute to an overall NIPP (see Annex D-3 for an overview of SPPA).

CARVER + Shock as a Tool to Conduct Vulnerability Assessments

Under the auspices of the White House Homeland Security Council, the White House Interagency Food Working Group was formed with representatives from various federal agencies (e.g., USDA, EPA, HHS, DoD) to discuss issues across all of the administration’s food programs. To comprehensively assess the food and agriculture supply, the group agreed that a single risk assessment model/tool—CARVER + Shock—would be used to harmonize all food and agriculture–related agency efforts.

CARVER + Shock, a military special operations forces acronym, enables cross-sector assessment of risks and vulnerabilities. The tool rates seven factors that affect the desirability of a target:

-

Criticality—public health or economic impact

-

Accessibility—physical access to target

-

Recuperability—ability of the system to recover from an attack

-

Vulnerability—ease of accomplishing the attack

-

Effect—amount of actual direct loss from the attack

-

Recognizability—ease of identifying target

-

Shock—combined measure of physical, health, psychological, and economic effects

CARVER + Shock enabled more in-depth analysis of a food production and distribution process and its vulnerabilities, while also adding the new factor of shock not considered in ORM assessments. The FDA and its counterparts had to learn this new tool and apply it to work already completed—termed “verifications”—and extend the assessment effort to cover new food and agriculture scenarios. These efforts again formed the foundation for strategic priorities, research directions, risk communication needs, and subsequent advice to industry with respect to food defense.

With congressional funding for security assessments of food and agriculture facilities, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) teamed with the FDA/USDA and DHS to harmonize food defense and law enforcement goals. CARVER + Shock was applied to a wide variety of high-priority food commodities in collaboration with state, federal, and industry experts on a facility-by-facility basis, and SPPA was launched. The Food and Agriculture Sector was viewed as the logical point of contact with industry to seek its voluntary participation in this endeavor. GCC co-chairs, SCC chairs, and the FBI developed SPPA so that issues of proprietary processes and potentially sensitive information would be handled properly. Findings or reports would be reviewed and approved by both industry and government before being issued as public documents, while government would retain the sensitive/classified assessments. A sufficient level of trust had been built within the Food and Agriculture Sector to accommodate this assessment program in what would become one of the Sector’s major accomplishments.

These assessments supported the requirements for a coordinated food and agriculture infrastructure protection program as stated in the NIPP; Sector-Specific Plans (SSPs); National Preparedness Guidelines (released in 2007); and HSPD-9, Defense of U.S. Agriculture and Food. Using CARVER + Shock, SPPA assessments were conducted on a voluntary basis among one or more industry representatives for a particular product or commodity, their trade association(s), and federal and state agricultural, public health, and law enforcement officials.

As a result of each assessment, participants identified individual nodes or process points that were of greatest concern, protective measures and mitigation steps that could reduce the vulnerability of these nodes, and research gaps/needs. Discussions of mitigation steps and good security practices were general in nature, focusing on physical security improvements for food processing facilities, biosecurity practices, and disease surveillance for livestock and plants. The results can be found in the 2008 SPPA final report summary, Strategic Partnership Program Agroterrorism (SPPA) Initiative: Final Summary Report, September 2005–September 2008 (FDA, 2009d).

From 2005 to 2007, 36 SPPA assessments were conducted on a variety of food and agriculture products, processes, or commodities. These assessments covered 1 or more of the SCC subcouncils’ commodities and were completed in 31 of the 52 key sites identified under the SPPA initiative. Each SPPA assessment lasted approximately 3 days and was conducted by a team of 20 to 30 participants from federal, state, and local agricultural, food, public health, and law enforcement agencies; food and agriculture companies; and their trade associations. In preparation for the assessment, the USDA or FDA federal host (Sector-Specific Agency [SSA]) and a representative of FBI headquarters provided background and educational material. This material ensured that participants were knowledgeable about the CARVER + Shock assessment tool and plans for the assessment. Recurring themes included the need for

-

better understanding of threat agent characteristics;

-

better scientific capabilities, such as the development or improvement of detection methods for threat agents of concern;

-

development or dissemination of models (or their results) related to the impact of a food or agricultural terrorism event;

-

improved communications; and

-

identification of gaps in evaluating economic impacts and effects on consumer confidence.

In addition to identifying gaps in knowledge, the tool has been used to determine commonalities across food and agricultural industries that make them more vulnerable to attack, allowing for the proposal of generic protective measures or mitigation strategies that could be beneficial to the industries assessed.

The SPPA initiative was a significant step toward hardening of critical infrastructure and greater protection of the food and agriculture industries. This was accomplished by providing industry members with training and hands-on experience with a terrorism-focused assessment. The SPPA initiative also provided federal, state, and local governments with an in-depth look at the vulnerabilities that may be associated with different facets of the food and agriculture industries. Finally, the initiative increased communication among industry, government, and law enforcement stakeholders concerned with the safety and security of the food supply.

To further assist industry and state and local government officials, various guidance has been published, such as USDA’s Guidelines for the Disposal of Intentionally Adulterated Food Products and the Decontamination of Food Processing Facilities (FSIS, 2006) and EPA’s Federal Food and Agriculture Decontamination and Disposal Roles and Responsibilities

(EPA, 2005). In addition, the FDA released a free software version of the CARVER + Shock assessment tool (FDA, 2009e).

Information Sharing

The Food and Agriculture Sector has made many attempts to find a suitable communication tool that fully supports its activities. Although the Food Marketing Institute3 (FMI) supported the Food and Agriculture Sector Information Sharing and Analysis Center as a mechanism for sharing data, FMI lacked sufficient private funds to offer more than a clearinghouse/e-mail notification system. While this was useful in the Sector’s early days, a more robust system was needed as its activities matured and broadened.

DHS and its component organizations developed several other information and analysis systems, such as the Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN). After almost 2 years of HSIN operation, staff have made the following recommendations for improving communications and Food and Agriculture Sector operations. First, hire a data manager to actively poll and issue information to all Sector representatives, who would in turn issue this information to all subsectors/members. Use HSIN and FoodShield, a network designed by and located at the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD), as mechanisms for communication. Second, re-fund SPPA as a joint FBI/DHS/FDA/USDA initiative to conduct CARVER + Shock assessments at food facilities, with state participation. Third, fund full-time positions to carry out state food defense activities. It was also suggested that DHS’s Homeland Infrastructure Threat and Risk Analysis Center’s annual infrastructure resource assessment is not serving Food and Agriculture Sector needs, even with more than 30 states using the current Food and Agriculture Sector Criticality Assessment Tool (FASCAT).

The collection of sensitive information continues to be a challenge. The FDA and its counterparts are subject to Freedom of Information Act4 (FOIA) requirements and must disclose information upon request unless it is excluded by a confidential business interest or is classified. Further, the FDA is subject to Paperwork Reduction Act5 provisions, which require justification to solicit, survey, or ask questions of consumers, industry, and others. Industry has been reluctant to share technical and production information for fear it would be available to the public through FOIA. Thus it is difficult to obtain survey data on industry practices. To overcome industry’s

reluctance to share technical and production information, a process to protect the information from FOIA, state and local disclosure laws, and civil lawsuits (DHS, 2009) was conceived—the Protected Critical Infrastructure Information (PCII) process. With this DHS/PCII process, the FDA has an avenue to receive and secure industry data. But the DHS/PCII data collection process requires substantive justification and industry cooperation. Further, DHS/PCII must concur in the agency’s request so the request can receive an expedited and abbreviated Office of Management and Budget review. The FDA has employed PCII in only two instances, in 2006 and 2008–2009, to survey milk processors in the United States, as discussed further in a later section.

The classification and sharing of sensitive information related to food defense have been both a burden and a blessing. HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson, meeting with state public health officials, promised that HHS would seek a secret-level clearance for each state health department, usually the director. However, receiving a security clearance has been a challenge given the volume of requests made at the federal, state, and industry levels; the fact that many high-level officials are appointees with frequent turnover; and the strict standards for gaining a clearance that are not always met. In the case of the Food and Agriculture Sector, the GCC co-chairs and SCC chairs have received security clearances, as have some subcouncil and task force members. Even with a security clearance, however, every individual is not assured of access to all classified information. Classified information is available only on a need-to-know basis. For purposes of the Food and Agriculture Sector, classified information6 is not available to the public. It may be gleaned from confidential sources or from compilations or analyses of existing public data that in the view of the government organization meet the definition of Title 18 of the U.S. Code.

Classified information generated by the FDA and other government agencies is secured from public access, stored in secure rooms or vaults, and accessed using a stand-alone, non-network computer or device. Like all government agencies, the FDA has specific procedures for transporting classified documents and for their storage or use. The FDA’s Office of Crisis Management (OCM) is responsible for establishing and enforcing the agency’s security rules. The FDA must maintain a log and document all access to classified materials. The agency is subject to a security audit on an annual basis, and adherence to procedures is strictly enforced. As noted

earlier, for example, the FDA’s list of agent–food combinations derived from ORM and CARVER + Shock risk assessments remains classified. The SPPA joint FBI/USDA/FDA facility assessment reports are also classified.

Because some information may be sensitive but not classified, the FDA created the category of For Official Use Only (FOUO) documents, to be shared in hard copy only and with those Food and Agriculture Sector members who need the specific details contained therein. However, this FOUO information is subject to release under FOIA. As an example, in 2005 the FDA shared FOUO information with the milk industry, state milk inspectors, and others for purposes of establishing a new preventive measure to reduce the threat from a selected agent (discussed further in a later section).

As in military applications, the FDA applies the gist of classified information in formulating plans and actions to secure the food supply. Hence, the FDA’s food defense program priorities, research priorities, targeted investigations, and testing are based on and consistent with classified and unclassified knowledge and information. Thus while classified information is available only to a few individuals with a need to know, its impact is shared through public action. Moreover, in the event of a threatened or actual attack, state officials, other government partners, and industry counterparts will have access to all relevant information. For example, the milk industry and state officials were provided with all relevant information regardless of its source (including information derived from classified and FOUO documents) to successfully implement a food defense preventive measure.

Outcomes

The NIPP is intended to identify critical assets and fund or assist in their protection (see Annex D-3 for an overview). Following each annual exercise to identify the Food and Agriculture Sector’s assets, using ORM/CARVER + Shock (defined above) or now FASCAT, the resulting submissions by states’ food and agriculture units have been deemed less qualified than those of other sectors, such as Transportation, Telecommunications, and Finance. Hence, no funding or direct program reinforcement has been generated to sustain state and industry efforts in support of Food and Agriculture Sector activities. It has been noted that the Food and Agriculture Sector’s assets, usually a system and not a single facility, do not fit well within the assessment criteria of DHS’s Infrastructure Protection model assessment. Therefore, DHS has not funded the protection of the Food and Agriculture Sector’s self-identified critical infrastructure/key resources to date.

Additionally, the Food and Agriculture Sector has not fulfilled its ambitious promise to dedicate research efforts and funding to addressing many

of the scientific questions and intervention needs identified in joint FDA/USDA/DHS exercises and initiatives, such as SPPA. The reason is not a lack of dedication or expertise, but limited funding and a diffuse research direction that have produced some results, but not quite enough. Since 2006, for example, the industry has pointed out the lack of a coordinated, comprehensive program review of research findings from all federal and academic programs. In interviews, it was mentioned that industry members were able to secure funding this year from DHS, FDA, and USDA to begin a comprehensive compilation and review of research findings by NCFPD. This funding in support of the Food and Agriculture Sector had to be generated outside the normal DHS Science and Technology and Infrastructure Sector funding system.

Crossroads and the Future

Industry interviews suggested that the Food and Agriculture Sector must transform itself to sustain active participation in the future. Those individuals and organizations that play a critical role do so at great expense, and with the poor economy, the number of qualified, interested, and available food industry experts is dwindling. Moreover, their time and attention will proportionally be diverted to more pressing food safety issues with the increased number of outbreaks occurring. Those interviewed also cited frustration that not enough value has been derived from the time, energy, and dedication they have expended on the NIPP. The SCC has indicated willingness to work with DHS/GCC on a “value proposition” to ensure greater value for participants’ time and energy, but change is also needed.

While not mentioned in interviews, another potential factor in the future role and continued existence of a robust and active Food and Agriculture Sector is the current proposed food safety and defense legislation, HR27497 (see Annex D-1), and similar Senate bills now being considered by Congress. It is unclear what impact new legislative authorities and enforcement tools will have on the Sector’s public–private partnership. It is anticipated that new legislation will fill many gaps and needs cited by the FDA in its FPP, such as recall authority. Most government officials interviewed stated that the legislation would be a welcome addition and go a long way in helping to achieve many FPP goals. But HR2749 proposes to require all food facilities to have food safety and defense plans. Therefore, the SCC and its members would no longer have a voluntary role, but a regulated one.

BIOTERRORISM LEGISLATION

As mentioned earlier, Congress passed legislation in 2002 giving the FDA four new authorities under the Bioterrorism Act of 20028 (Table D-2). Their implications for the FDA are briefly described in this section.

Registration of Food Facilities

This authority requires food manufacturers, processors, holders, and distributors to register each facility, not company, with the FDA. As noted, the registration coverage is limited and does not encompass farm to table, specifically excluding farms and retail establishments. The purpose is to assist the FDA in conducting investigations more efficiently and effectively by having the facility name and location, products produced, and responsible official for contact. The FDA is prohibited from requiring electronic registration and so must also accept paper registrations.

While the FDA has received nearly 400,000 domestic and foreign registrations, it does not have audit authority (to check and revise data entered if mistakes are made), but must ask the submitter to make all corrections. Further, food facilities go in and out of business regularly, and again the system requires the submitting food facility (company) to make all corrections and deletions. The FDA believes the system does contain errors and is seeking legislation, in accordance with FPP needs, to make the registrations more current and accurate. The proposed HR2749 provides for this.

Prior Notice Rule

With the implementation of the prior notice rule, the FDA established a 24/7 prior notice data review function. This, again, was a new and unprecedented effort on the FDA’s part; no other FDA front-line operation was 24/7. The Office of Regulatory Affairs’s (ORA’s) Office of Regional Operations and Division of Import Operations created the Prior Notice (PN) Center, collocated with U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP’s) targeting center in Reston, Virginia. With 24/7 dedicated service, the PN Center requires a full-time staff. The PN Center and CBP’s targeting center staff, working together, have improved coverage not just of suspect foods, but of all imported foods.

Upon review and analysis of PN data and using an algorithm to target suspect shipments, the PN Center assigns activities for FDA and/or CBP investigators around the country to inspect, seize, or sample shipments for

surveillance and/or compliance purposes. It should be noted that the FDA’s staffing levels for imported foods do not allow coverage of all possible U.S. ports of entry—roughly 300 in number (see also Appendix E). The FDA covers fewer than 100 ports of entry on a regular basis. CBP staffs each port of entry and, when needed and available, is called upon by the FDA to carry out activities under the Bioterrorism Act or the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA)9 or other surveillance and compliance activities. For CBP to perform on behalf of the FDA, its officers must be commissioned. Commissioning permits federal and state officials to operate under the FDCA and enables those commissioned to carry out their responsibilities in reviewing FDA information. They are protected from the disclosure provisions of FOIA. The FDA has commissioned 9,500 CBP officers to expand its coverage.

From interviews, it appears that the PN Center has worked fairly well, and the FDA is apparently satisfied with it. The agency has noted that PN compliance and targeting of suspect imported foods would be improved, however, if additional needs articulated in the FPP were met. Namely, industry compliance would be greatly improved with better registration requirements. The FDA could also leverage host country competent authorities through formal cooperative agreements ensuring that food facilities in their country are complying. The FDA lacks sufficient staff to inspect all foreign food facilities and thus must preferentially target high-risk facilities for inspection to use its limited resources wisely.

Record Keeping

Record keeping requires each domestic food manufacturer, processor, holder, or distributor to retain records of incoming ingredients and supplies and of outgoing products. Since its implementation in 2004, the FDA has become more efficient and adept in meeting the SAHCDHA (serious adverse health consequences or death to humans or animals) standard for access to records. The FDA has used this authority to seek trace-back in a number of recent foodborne illness outbreaks, such as salmonella in tomatoes and melamine in pet food and infant formula.

Unfortunately, industry’s record-keeping compliance remains less than adequate. In 2009, the HHS Inspector General’s office conducted a survey of food facilities randomly selected from the FDA’s registration database. The report of the survey concludes that most food manufacturers and distributors cannot identify the suppliers or recipients of their ingredients or products despite federal rules requiring them to do so. A quarter of the food facilities contacted by investigators as part of the study were not even

aware that they were supposed to be able to trace their suppliers. The FPP identifies the need to correct this problem, and the proposed HR2749 legislation provides for this.

Administrative Detention

Administrative detention gives the FDA domestic embargo authority whereby suspect or contaminated food in commercial channels can be stopped until judicial action is taken to seize and/or destroy it. However, this authority again requires that the FDA meet the SAHCDHA standard before holding food in domestic commerce. In interviews, FDA officials indicated that this authority has not been employed to date, and the agency continues to request state embargo authority to hold such suspect foods while seeking judicial action.

INFORMATION GATHERING AND SHARING

Intelligence Information on Threats

Since 2002, the FDA has undertaken some food defense actions based on intelligence information or increased threat level alerts from DHS. Through its Office of Criminal Investigations (OCI), the FDA has long-established linkages with the FBI and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), as well as a network of agents nationwide gathering surveillance information. OCI in turn has liaisons in each FDA center and the Office of Emergency Operations. On a weekly basis, OCI meets with FBI and CIA representatives to review intelligence information and leads. Further, on a monthly basis OCI convenes a meeting of FDA, DHS, USDA, DoD, Defense Threat Reduction Agency, National Center for Medical Intelligence, FBI, and CIA colleagues to discuss recent intelligence information and other matters. Through these intelligence sources and analyses, the FDA is notified 24/7 of information that may impact an FDA-regulated product, which in turn may trigger FDA emergency procedures.

When DHS heightens its alert level to orange or red, the FDA, through established corresponding readiness procedures, also takes steps in case FDA-regulated products are impacted. During the early years of the food defense initiative, intelligence reports would most often indicate a non-specific threat or a threat to a non-FDA-regulated product, such as a threat to the transportation sector. Nonetheless, the FDA placed its personnel and operations on readiness alert. If the alert was specific to an FDA-regulated product, the agency would mobilize its resources to deal with the event.

Inspectional Activities and Industry Training

The FDA performs 10,545 food inspections annually, conducted by its own workforce and through state contracts. So it is clear that when the FDA trains its workforce, it must also train the states to ensure that consistent standards are applied. As FDA inspectors became more experienced with food defense measures, moreover, they routinely offered recommendations to, or shared educational materials with, industry facility management as part of their regular food safety inspections. The FDA, along with USDA/FSIS, has developed training materials, web-based tutorials, and awareness training modules for use by government and industry (FDA, 2009f).

The FDA also partnered with international institutions in an effort to broaden the U.S. food supply protections. Examples include a workshop with G8 countries on conducting vulnerability assessments, a workshop on conducting vulnerability assessments for Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) economies, a follow-on workshop on developing a food defense infrastructure for APEC, and a workshop on food defense infrastructure for Middle East Partnership Initiative countries.

The FDA also carried out specific, targeted food defense activities in which its investigators and scientists were directed to conduct inspections, sample collections, and test for potential threats to the food supply. The activities served to train FDA staff through practice and the application of food defense measures, new test procedures, and data collection methods, and were not expected to uncover actual threat agents. In contrast to regular and routine food inspections, the FDA chose to inform food trade associations and member companies of these activities so as not to cause alarm.

Finally, in 2008–2009, the FDA carried out special event activities during the preparations for the Democratic and Republican National Conventions as well as the presidential inauguration. These activities involved ensuring food safety and security.

FDA Research

As has been discussed, FDA scientists, economists, and others were instrumental in designing and shaping the risk assessment tools used for setting food defense priorities and targeting FDA resources most effectively. The FDA’s fiscal year (FY) and strategic long-range research plans have always been informed by its knowledge and understanding of classified and unclassified information, agent–food lists, and SPPA facility reports identifying research questions or needs. On the basis of this information, the FDA publicly identifies strategic research needs that, when fulfilled, will meet its food defense priorities. The four major areas of interest are

-

development of methods for the detection of biological and chemical agents in foods,

-

development of prevention technologies for use by the industry,

-

stability of chemical and microbiological agents when subjected to food processing activities, and

-

oral infectious/toxic dose of a biological or chemical agent when ingested with a food.

Collaborative food defense research is conducted in and through the following:

-

CFSAN Office of Regulatory Sciences, with biosafety level (BSL)-4 laboratory capability;

-

ORA’s field laboratories and research centers, also with BSL-4 capability;

-

the National Center for Food Safety and Technology, one of the FDA’s cooperative research centers, focused on food processing and technology;

-

NCFPD, a DHS Office of Science and Technology Center of Excellence, consisting of a consortium of universities;

-

USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS);

-

USDA’s Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, a research grant agency;

-

EPA’s Office of Research and Development;

-

DoD’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases; and

-

other academic partners through competitive grants from federal sources.

Collaborations with the above organizations remain extremely important to advance the FDA’s research priorities and to find solutions, preventive measures, and tools for reducing or eliminating food defense risks. During interviews, however, it became clear that staffing for the agency’s food defense research coordination, oversight, and direction is inadequate. If the FDA is to retain and improve its scientific knowledge base and its ability to solve food defense problems, it will need to fill this gap. Further, a robust strategic research plan is needed to set more specific priorities, such as which agents are most important and what technologies are most promising. The lack of such a plan will perpetuate a diffuse research agenda that satisfies the needs of neither government nor regulated industry nor, ultimately, consumers.

A detailed summary of the FDA’s 2007 food defense research accomplishments is shown in Table D-3.

TABLE D-3 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Food Defense Research Accomplishments, 2007

|

Topic |

Findings |

|

Stability of chemical and microbiological agents when going through the manufacturing process |

|

|

Oral toxicity of toxins produced by microorganisms |

The results of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test for ricin and abrin in phosphate-buffered saline, apple juice, half-and-half, and bottled spring water provided a reliable indication of the amount of ricin and abrin present in each of the beverages. Differences were observed in the toxicity of ricin and abrin in phosphate-buffered saline > apple juice ≥ water ≥ half-and-half. |

|

Effectiveness of detection methods in different food matrices |

The evaluated system is capable of identifying as few as 10 colony forming units (CFU)/ml (or CFU/g) of F. tularensis live vaccine strain in infant formula, liquid egg whites, and lettuce and displays a broad range of detection of 108 CFU/ml (or CFU/g) to 101 CFU/ml (or CFU/g). |

|

SOURCE: See http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodDefense/FoodDefensePrograms/FoodDefenseResearchReports/default.htm (accessed October 8, 2010). |

|

INFRASTUCTURE FOR FOOD DEFENSE

The FDA has probably undergone its greatest transformation in the area of food defense–related scientific testing and investigation. A significant number of changes focused on facility and personnel safety were required for proper handling of bioterrorism and other selected agents. Laboratory space had to be isolated so that high-dose or large amounts of chemicals/bacteria/toxins would not infiltrate other laboratory areas when sensitive testing was conducted on contaminants. Research on these agents posed a safety risk requiring special clothing, air/hood systems, and storage and disposal procedures.

The FDA established new procedures and conducted training and performance testing to ensure that its laboratories, and the broader Food Emergency Response Network (FERN), would be able to detect potential threat agents in a wide variety of foods. It was not a trivial matter to determine the adequacy of test methods when new foods were involved. Many of the chemicals and microbial agents of interest had not been investigated in FDA laboratory environments because natural barriers usually precluded their occurrence as contaminants in foods. Often adjustments of existing methods were sufficient, but at times whole new methods of extraction and detection were needed.

The FDA also undertook an extensive quality assurance program to ensure consistent application of microbial and chemical test methods and the accuracy of results across of all of its laboratories. Upon the formation of FERN, the quality assurance function was augmented, and state-of-the-art equipment for the laboratories was needed.

Currently there are 157 FERN laboratories: 35 federal, 111 state, and 11 local. These laboratories are staffed with 120 microbiological, 105 chemical, and 35 radiological scientists and staff. They carry out method development/validation; proficiency testing (in radiology, chemistry, and microbiology); surveillance testing; and electronic communications and collaboration. The FDA has mobilized the FERN laboratories to deal with a number of recent outbreaks, such as E. coli O157:H7 in spinach (2006), Salmonella in peppers (summer 2008), melamine in plant protein (2007), Salmonella in peanut butter (2009), and melamine in milk products (2008–2009). This new capacity, developed with food defense funds, has been a true asset in responding to public health emergencies, and reflects the assimilation of food defense and safety into the FDA’s FPP.

An episode in 2005 tested the FDA’s risk assessment and research capacity and demonstrated that the FDA, the milk industry, and the states were prepared to act quickly and effectively. All gained a better appreciation of the time and effort required to address potential food defense threats and the essential role of the new food defense capabilities as well as existing food safety systems. An article was published in a scientific journal that had the potential to frighten U.S. consumers, rather than depicting the scientific and technical challenges of protecting the U.S. food supply, in this case milk. This article described a mathematical model for the farm-to-table milk production system wherein a single milk-processing facility was the victim of a deliberate release of botulinum toxin into milk (Wein and Liu, 2005). The article suggested that if a terrorist could obtain enough toxin and introduce it into milk, rapid distribution and consumption could cause hundreds of thousands of poisonings.

The FDA and the industry were worried that the release of information on the effect of pasteurization on a terrorism hazard would cause a panic among U.S. consumers and provide a road map for a terrorist. The FDA and milk industry and state officials focused efforts on reducing the vulnerability of, and risk to, the milk supply by modifying the pasteurization parameters. Following these efforts, the FDA, using state milk inspectors, conducted surveys in 2006 and 2008–2009 to assess industry’s voluntary compliance with the new parameters. Both surveys showed that better than 75 percent of milk processors had complied, thus reducing the risk to the milk supply from such an intentional contamination. This response by the FDA, the milk industry, and the state governments demonstrated their capacity to react quickly to a necessary technological change.

EMERGENCY RESPONSE

Preceding sections of this appendix have detailed FDA efforts to prevent an attack on the nation’s food supply. Should such an attack occur,

however, the FDA and the administration, through the leadership of DHS, have procedures, networks, and capabilities in place to respond.

From the outset of the HHS bioterrorism efforts and the DHS/FDA/USDA food defense initiative, emergency response has been a key component. HHS’s Office of Public Health Emergency Preparedness, as well as the FDA’s OCM, Office of Emergency Operations, and center counterparts, developed all-hazard emergency response procedures to deal with a contaminated FDA-regulated product. In accordance with the relevant HSPD to employ the National Incident Management System (NIMS) in support of the NRP, the FDA adopted NIMS.

OCM also instituted continuity-of-operations planning, whereby the FDA and its suborganizations have an alternative site for operations should an attack or threat occur. Each suborganization had to identify essential personnel who would move to this alternative site to maintain operations, while others would be instructed to stay home and seek safety.

The FDA has conducted exercises and participated in HHS and DHS/administration training efforts to improve its preparedness, fill gaps in, or correct procedures and capacities as needed. The FDA also participated in the administration effort to review and update the NRP.

As mentioned earlier, if intelligence or FDA surveillance indicated a threat to an FDA-regulated product, this information would be communicated directly to OCM. OCM would in turn trigger its emergency response procedures, including notifying all relevant federal, state, and industry counterparts.

FOOD DEFENSE WITHIN THE FDA’S FPP

Prior to 2007, food defense and food safety program resources were usually separate in budgeting, program planning, and program goals and objectives. In 2007, the FDA combined the two under the FPP. In the context of its oversight of ever-increasing imported food shipments, a spate of domestic and imported food outbreaks, and numerous other factors, the FDA has proposed the FPP as its strategic plan for marshaling all of its expertise, systems, capabilities, and capacities to prevent, intervene in, and respond to food-related threats.

The FY 2010 FPP budget projects total full-time equivalents (FTEs) at 3,288 and funding of $8,455.8 million. This represents an increase of nearly 500 FTEs, but no increase in funding. Total FTEs for the animal drugs and feeds program are projected at 767, an increase of 105 FTEs, with funding of $171 million. The FTEs and funding are distributed among CFSAN, Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) headquarters, and ORA field operations for research scientists, regulatory review, program analysts, investigators, compliance, laboratory operations, etc.

The food defense components of the plan are as follows:

-

The FDA will improve its ability to protect American consumers and strengthen the safety and security of the food supply chain by working with domestic and foreign industry to develop new control measures for all levels of food production and processing. The FDA will also verify that these control measures are effective when implemented.

-

The FDA will strengthen food safety by improving the science on which regulatory decisions and enforcement rely. The agency will conduct risk analysis, modeling, and evaluation to improve risk-based decision making so it can better target resources to high-risk foods. This work will also include improving the FDA’s ability to attribute contamination to specific foods and thereby promote faster response and better resource targeting.

-

The FDA will work with the food industry, consumer groups, and federal, state, local, and foreign partners to identify and generate the additional data needed to improve understanding of food vulnerabilities and risks. This information will be used to strengthen food safety and defense.

-

The FDA will expand state capacity to perform risk-based inspections by increasing the number of cooperative agreements and partnerships with states.

-

The FDA will increase the number of chemical laboratories under the FERN program through cooperative agreements. The agency will also invest in high-volume laboratories for better sample analyses and faster testing.

-

The FDA proposes establishing a new strategic framework for an integrated national food safety system. To achieve this objective, the FDA must build new and expand existing programs and relationships with its federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial regulatory partners. This will allow the FDA to increase information sharing and improve the quantity and quality of food safety data it receives from its food safety partners.

-

The FDA will conduct research in high-priority areas, such as reducing the risk of E. coli in produce. The agency will speed its response to outbreaks by developing and validating technologies for subtyping pathogens and developing, evaluating, and deploying rapid detection tests.

-

Working with its federal and state partners, the FDA will develop a Pet Event Tracking Network for early reporting of contaminated feed.

-

The FDA will conduct research designed to limit the adverse health effects of intentional and unintentional contamination of food.

-

The FDA will upgrade and integrate the information technology systems it uses to screen, sample, detain, and take enforcement actions against imported products. This effort includes developing and validating an accurate database of registered foreign facilities as well as designing and using risk-based software algorithms for import targeting.

-

The FDA will improve the speed and effectiveness of its response to contamination by strengthening its ability to collect and analyze information necessary to trace products during a food emergency. The agency will also collaborate with state veterinary diagnostic laboratories to ensure more timely and accurate reporting and analysis of feed contamination.

-

The FDA will aggressively strengthen its response to food-related events by instituting a more robust incident command system that fully integrates modern incident command principles into its emergency operations. The agency will also improve how it communicates with the public about food-related emergencies to ensure that such communications better meet the health and information needs of consumers.

As context for the above FY 2010 projected resources and anticipated accomplishments, it is important to review food defense budgeting and staffing generally to date. As mentioned previously, at the start of the food defense initiative, the FDA and its federal and state counterparts had no food defense experts on staff and could not hire any because none existed except for physical security experts. Therefore, food defense expertise was developed by current food safety staff and scientists. And as food defense and bioterrorism resources were appropriated, the FDA retrained and reclassified existing food safety professionals and staff to meet these obligations. This was done because, as food defense was receiving new funding, food safety funding was diminishing to the extent that FTEs and valuable expertise were being lost. Although some new staff were hired and trained over time, it was important for the FDA to retain its food safety expertise. For the near term, it redirected these resources to food defense research, training, education, risk communication, and compliance issues and problems.

Further, many of the systems and operations initiated for food defense were built upon and/or added to existing food safety operational components. So in essence, food defense and safety share resources. Therefore, for a particular fiscal year’s budget and planning, the FDA can use its existing FTE resources for either program. The agency has thereby maintained a

dual focus in the face of dwindling resources, ensuring its ability to meet the full range of challenges to the food supply.

From interviews with FDA officials, it appears that currently there are a small number of FTEs dedicated to food defense in the areas of prevention, intervention, and response. While a dual focus has proven beneficial and prudent for the FDA’s strategic purposes, it has also stretched and diminished the agency’s food defense capacity and capabilities when food safety concerns have been a higher priority. Those interviewed mentioned the FDA’s inability, due to a lack of available staff, to work on research collaboration and coordination as one example. It appears clear that the FDA does not have a dedicated food defense organizational unit(s) of sufficient critical mass to (1) sustain the development and coordination of CFSAN programs, training, and risk communications; (2) fulfill the FDA’s leadership and participation with the Food and Agriculture Sector; and (3) direct, coordinate, and fund the research program on an intramural as well extramural basis.

SUMMARY AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVEMENT

In 2001, the FDA began to define and build an intentional contamination program capacity within its food programs at CFSAN, CVM, and ORA, in line with the bioterrorism preparedness initiatives of HHS and CDC. That same year, Congress passed the Bioterrorism Act of 2002,10 giving the FDA new authorities to better address threats from imported foods, to trace contaminated foods in distribution through record keeping, to detain contaminated foods in domestic commerce when deemed to be a serious danger to humans or animals, and to establish a database of all food producers worldwide so as to better target inspections and emergency response activities. In 2003, the administration reorganized to focus on domestic and border security functions, moving many domestic security programs from several departments to the new DHS.

The FDA, along with its federal food safety counterparts, had to forge a new working relationship with DHS to achieve its food defense goals and objectives. Through DHS’s mission and scope of authorities, coupled with a series of HSPDs, the federal government, in cooperation with state, local, and industry counterparts, pursued an expanded effort to protect the nation’s food supply from intentional attacks. A government–industry partnership—the Food and Agriculture Sector—allowed the FDA and other federal agencies to communicate, cooperate, and work more closely with regulated industry. The goal was to conduct vulnerability assessments and

identify the key critical assets within the food and animal feed systems. Using this information, the Food and Agriculture Sector’s critical infrastructure protection plan, the SPPA initiative, was submitted as part of the NIPP.

Even with dedicated participation by both government and industry members, however, the Food and Agriculture Sector effort has been only moderately successful. The most recognized achievement is development of the SPPA initiative. Although the efforts expended by all members of this partnership have generated some valuable outcomes and deliverables, the general sense from industry, states, and some federal officials is that the efforts did not yield corresponding value. The FDA has built strong working relationships with its federal partners at HHS/CDC; USDA’s FSIS, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, and ARS; EPA; DoD; and DHS. Through these partnerships, the FDA has leveraged and shared expertise, capabilities, and insight into how better to protect the nation’s food supply.

In 2007, the FDA published its FPP, a strategic plan that combines food defense and safety into a single program. Since then, available resources have been applied in several instances to minimize the impact of food hazards in a rapid and effective manner. For example, the FERN laboratories have been activated to expand testing for Salmonella St. Paul in recent outbreaks associated with tomatoes/salsa. Bioterrorism record-keeping authority has been implemented to trace melamine-contaminated foods and animal feeds. In future budget and research planning, it will be even more important to assess relative risk in the areas of food defense and safety and to set priorities so the FDA can apply its core capacities and resources where most needed. However, combining food safety and defense priorities in a systematic and transparent process is necessary to fully integrate the components of the FPP.

As the FPP states, the FDA has devoted its food defense/protection efforts to preventing, intervening in, and responding to potential threats to the food supply. Over the years, the FDA has received additional funding for its food defense and bioterrorism program and activities. The agency has applied these funds primarily by redirecting existing scientific, program, and technical personnel to the food defense program. In so doing, the FDA has preserved its core food safety capacity and expertise while focusing its priorities on food defense issues. For example, the FDA embarked on an ambitious testing and research program; established appropriate facilities, such as BSL-4 laboratories; developed safety procedures for handling selected agents; established an expanded network of laboratory facilities (FERN) to gain surge capacity; and funded investigations for high-priority agents. Today, the agency is better equipped to respond to a chemical or microbial threat to the food supply.

At the same time, even the best planning efforts are limited by the inability to predict the future. Therefore, it is critical to retain functional expertise, capacity to act, and scientific knowledge to respond to both emerging food defense and safety events. From interviews with officials and a review of FY 2010 priorities, however, it appears that the food defense program’s research and oversight functions possess less than critical mass. A review of the food defense program’s progress and interviews with government and industry officials make it clear that the FDA needs additional legal authorities and technical improvements to manage and support a more functional food protection program. Congressional bills currently being discussed contain authorities to identify domestic and foreign food facilities through annual/biannual registration, to trace contaminated food products through records and impose fines when failures occur, to require food safety and defense prevention plans at each food facility or allow the FDA to impose fines for failures to maintain such plans, and to issue mandatory recall/stoppage of contaminated foods in commercial channels. With these additional legal authorities and associated funding, the FDA should have sufficient means to meet its ambitious goals for improving the overall safety of the nation’s food supply.

Based on the information in this appendix, the author has identified the following opportunities for greatly improving the ability of the FDA to protect the public against potential intentional contamination of the nation’s food supply:

-

Develop the Food and Agriculture Sector partnership of a greater “value proposition” (i.e., a new mode of operation with valuable outcomes), acceptable to the GCC and SCC, that would address all hazards, encompassing food defense, natural disasters, nationwide events, and other challenges outlined in the FDA’s FPP.

-

Develop and apply a mechanism for prioritizing combined food defense and safety risks and generating a single ranked listing of food protection priorities for purposes of strategic, long-range planning.

-

Develop a sufficient critical mass of core capacities, staff, and resources in the food defense program to (1) sustain the development and coordination of CFSAN and CVM programs, including training and risk communications; (2) fulfill the FDA’s co-lead position on the GCC; and (3) direct, coordinate, and fund the agency’s research program on a intramural as well extramural basis.

-

Enact legislation and associated appropriations so the FDA has the legal and operational tools needed to achieve the FPP’s goals and objectives.

ANNEX D-1

SUMMARY OF HR2749,11 PROPOSED FOOD PROTECTION LEGISLATION

-

Creates an up-to-date registry of all food facilities serving American consumers: Requires all facilities operating within the United States or importing food to the United States to register with the FDA annually.

-

Generates resources to support FDA oversight of food safety: Requires payment of an annual registration fee of $500 per facility to generate revenue for food safety activities at the FDA.

-

Prevents food safety problems before they occur: Requires foreign and domestic food facilities to have safety plans in place to identify and mitigate hazards. Safety plans and food facility records would be subject to review by FDA inspectors and third-party certifiers.

-

Increases inspections: Sets a minimum inspection frequency for foreign and domestic facilities. Each high-risk facility would be inspected at least once every 6 to 12 months; each low-risk facility would be inspected at least once every 18 months to 3 years; and each warehouse would be inspected at least once every 5 years. Refusing, impeding, or delaying an inspection would be prohibited.

-

Requires demonstrating safety for food imports: Directs the Secretary of HHS to require certain foreign foods to be certified by third parties accredited by the FDA as meeting all U.S. food safety requirements.

-

Creates a fast-track import process for food meeting security standards: Directs the FDA to develop voluntary safety and security guidelines for imported foods. Importers meeting the guidelines would receive expedited processing.

-

Requires safety plans for fresh produce and certain other raw agricultural commodities: Directs the FDA, in coordination with USDA, to issue regulations for ensuring the safe production and harvesting of fruits and vegetables and other raw agricultural commodities, such as mushrooms.

-

Improves traceability: Significantly expands the FDA’s trace-back capabilities in the event of a foodborne illness outbreak. Directs HHS to issue trace-back regulations that enable the Secretary to identify the history of the food in as short a time frame as prac-

-

ticable, but no longer than 2 business days. Prior to issuing such regulations, the Secretary would be required to conduct a feasibility study, public meetings, and one or more pilot projects. There would be exemptions for certain foods or facilities.

-

Requires country-of-origin labeling: Requires labels on all processed food to indicate the country in which final processing occurred. Requires country-of-origin labeling for all produce.

-

Expands laboratory-testing capacity: Requires the FDA to establish a program for recognizing laboratory accreditation bodies and to accept test results only from duly accredited laboratories. Requires laboratories to send certain test results directly to the FDA.

-

Provides strong, flexible enforcement tools: Provides the FDA new authority to issue mandatory recalls of tainted foods. Strengthens penalties imposed on food facilities that fail to comply with safety requirements.

-

Advances the science of food safety: Directs the Secretary to enhance foodborne illness surveillance systems so as to improve the collection, analysis, reporting, and usefulness of data on such illnesses. Requires the Secretary to provide greater coordination among federal, state, and local agencies.

-

Enhances the transparency of the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) program: Requires posting on the FDA’s website of documentation submitted to the FDA in support of GRAS notification.

-

Allows the FDA to charge a fee to cover the cost of additional inspections of facilities that previously committed a violation of the act related to food.

-

Enhances oversight of the safety of new infant formulas: Requires that the manufacturer of a new infant formula submit certain safety information regarding new ingredients. Grants the FDA additional time to review such new ingredients.

-

Enhances the FDA’s ability to administratively detain tainted food products.

-

Allows the Secretary to prohibit or restrict the movement of harmful food products: If the Secretary, after consultation with the governor of a state, determines there is credible evidence that an article of food presents an imminent threat, he or she can prohibit or restrict movement of that food in the state or portion of the state.

-

Creates an up-to-date registry of importers: Requires all importers of foods to register with the FDA annually and pay a registration fee.

-

Requires unique identification numbers for facilities and importers: To improve the accuracy of data and the ability of the FDA to identify parties involved in a crisis situation more quickly, creates unique identification numbers for all food facilities and importers.

-

Provides protection for whistleblowers that bring attention to important safety information: Prohibits entities regulated by the FDA from discriminating against an employee in retaliation for assisting in any investigation regarding any conduct the employee reasonably believes constitutes a violation of federal law.

-

Grants the FDA new authority to subpoena records related to possible violations.

ANNEX D-2

AUTHORITIES

Under the FDCA,12 the FDA regulates 80 percent of the nation’s food supply, including all foods and animal feeds except for meat, poultry, and egg products, which are regulated by USDA. The FDA may take enforcement action when a food or feed is found to be adulterated. The term “adulteration” is defined in section 402 of the act. The FDA’s food programs also operate under the following legal authorities: the FDCA; the Federal Import Milk Act;13 the Public Health Service Act;14 the Food Additives Amendment of 1958;15 the Color Additives Amendments of 1960;16 the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1966;17 the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974;18 the Saccharin Study and Labeling Act of 1977;19 the Infant Formula Act of 1980;20 the Drug Enforcement, Education, and Control

|

12 |

FDCA, Public Law 75-717, 75th Cong., 3rd sess. (June 24, 1938). Codified as Title 21 U.S. Code, Section 9. |

|

13 |

Federal Import Milk Act, Title 21 U.S. Code, Chapter 4 §141-149. |

|

14 |

Public Health Service Act, Public Law 78-410, 78th Cong., 2nd sess. (July 1, 1944). |

|

15 |

Food Additives Amendment of 1958, Public Law 85-929, 85th Cong., 2nd sess. (September 6, 1958). Codified as Title 21 U.S. Code § 321. |

|

16 |

Color Additives Amendments of 1960, Public Law 86-618, 86th Cong., 2nd sess. (July 12, 1960). Codified as Title 21 U.S. Code § 321. |

|

17 |

The Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1966, Public Law 89-755, 89th Cong., 2nd sess. (November 3, 1966). |

|

18 |

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974, Public Law 93-523, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess. (December 14, 1974). |

|

19 |

Saccharine Study and Labeling Act of 1977, Public Law 95-203, 95th Cong., 1st sess. (November 23, 1977). |

|

20 |

Infant Formula Act of 1980, Public Law 96-359, 96th Cong., 2nd sess. (September 26, 1980). |

Act of 1986;21 the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990;22 the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994;23 the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996;24 the Federal Tea Tasters Repeal Act of 1996;25 the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996;26 the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997;27 the Antimicrobial Regulation Technical Corrections Act of 1998;28 the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002;29 the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004;30 the Sanitary Food Transportation Act of 2005;31 the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act;32 and the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007.33 USDA regulates meat, poultry, and egg products under the Meat and Poultry Act, largely through premarket inspection and approval for sale.

Both the FDA and USDA have limited food defense enforcement authority, except for the Bioterrorism Act of 2002. Most of their initiatives are voluntary. Hence the food defense program, even at USDA with its authority to withhold its seal of approval, has been limited to issuing guidance and working with industry to encourage participation in food defense activities.

ANNEX D-3

OVERVIEW OF THE NIPP

HSPD-7 identifies 17 critical infrastructure and key resources (CIKR) sectors and designates federal government SSAs for each of the sectors. Each sector is responsible for developing and implementing an SSP and providing sector-level performance feedback to DHS to enable assessment of national cross-sector CIKR protection program gaps. SSAs are responsible for collaborating with private-sector security partners and encouraging the development of appropriate information sharing and analysis mechanisms within the sector. HSPD-9 establishes a national policy to defend the food and agriculture system against terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies.

SECTOR OVERVIEW

The Food and Agriculture Sector has the capacity to feed and clothe people well beyond the boundaries of the nation. The Sector is almost entirely under private ownership and is composed of an estimated 2.1 million farms, approximately 880,500 firms, and more than 1 million facilities. This Sector accounts for roughly one-fifth of the nation’s economic activity and is overseen at the federal level by USDA and the FDA within HHS.

USDA is a diverse and complex organization with programs that touch the lives of all Americans every day. More than 100,000 employees deliver more than $75 billion in public services through USDA’s more than 300 programs worldwide, leveraging an extensive network of federal, state, and local cooperators. One of USDA’s key roles is to ensure that the nation’s food and fiber needs are met. USDA is also responsible for ensuring that the nation’s commercial supply of meat, poultry, and egg products is safe, as well as protecting and promoting U.S. agricultural health.

The FDA is responsible for the safety of 80 percent of all of the food consumed in the United States. While its mission is to protect and promote the public health, that responsibility is shared with federal, state, and local agencies; regulated industry; academia; health care providers; and consumers. The FDA regulates $240 billion of domestic food and $15 billion of imported food. In addition, roughly 600,000 restaurants and institutional food service providers, an estimated 235,000 grocery stores, and other food outlets are regulated by state and local authorities that receive guidance and other technical assistance from the FDA.

The Food and Agriculture Sector is dependent upon the Water Sec-

tor for clean irrigation and processed water; the Transportation Systems Sector for movement of commodities, products, and livestock; the Energy Sector for powering of the equipment needed for agricultural production and food processing; and the Banking and Finance, Chemical, Dams, and other sectors as well.

SECTOR PARTNERSHIPS

In 2004, the Food and Agriculture Sector Coordinating Council (FASCC) was formed. The FASCC comprises a GCC and a private-sector coordinating council. The FASCC hosts quarterly joint meetings that provide a public–private forum for effective coordination of agriculture security and food defense strategies and activities, policy, and communications across the entire Sector to support the nation’s homeland security mission. It provides a venue for mutually planning, implementing, and executing Sector-wide security programs, procedures, and processes, as well as for exchanging information and assessing accomplishments and progress in defending the nation’s food and agriculture critical infrastructure. It is a central forum for introducing new initiatives for mutual engagement, evaluation, and implementation; issue resolution; and mutual education. Joint initiatives include identifying and prioritizing items that need public–private input, coordination, implementation, and communication; coordinating and communicating issues to all members; and identifying needs/gaps in research, best practices/standards, and communications.

PRIORITY PROGRAMS

The SPPA Initiative

To assist in protecting the nation’s food supply, the FBI, DHS, USDA, and HHS/FDA developed a joint assessment program—the SPPA initiative. This initiative included a series of assessments of the Food and Agriculture Sector in collaboration with private industry and state volunteers. These assessments supported the requirements for a coordinated food and agriculture infrastructure protection program as stated in the NIPP, SSPs, and HSPD-9. SPPA assessments were conducted on a voluntary basis among one or more industry representatives for a particular product or commodity, their trade association, and federal and state government agricultural, public health, and law enforcement officials. Together they conducted a threat assessment of that industry’s production process, enabling the participants to identify nodes or process points of highest concern, protective measures and mitigation steps that could reduce the susceptibility of these nodes, and research gaps and needs. Between November 2005 and May 2008, the