4

Primary Care

NURSE PRACTITIONERS AS LEADERS IN PRIMARY CARE

Having access to health insurance does not necessarily mean having access to primary care services or access to high-quality, efficient health care, said Tine Hansen-Turton, the CEO of the National Nursing Centers Consortium and executive director of the Convenient Care Association. For example, when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts passed health care reform legislation in 2007, more than 300,000 people got a new insurance card. However, emergency rooms were immediately flooded with patients, and physicians’ offices had to quit accepting new patients because of the overwhelming demand. “We learned some very important lessons from Massachusetts,” said Hansen-Turton—one of which is that the nursing workforce needs to be prepared and empowered to deliver primary care. Nurse practitioners are “ready, willing, and able to be primary care providers and a partner in this crisis,” she said.

The State of Pennsylvania has devoted considerable attention to the development and use of the nursing workforce. For example, legislation has expanded the scope of practice for nurses and has reduced some of the barriers for nurse practitioners and other clinical nurse specialists to practice to their greatest potential in the state (Hansen-Turton et al., 2009). The state also has invested in the Chronic Care Model that Governor Rendell described during his remarks; as he noted, this model uses nurse practitioners and primary care physicians in a medical home format to reach three-quarters of a million patients.

Nurse-Managed Health Clinics

Another important way to provide health care, particularly to vulnerable populations, is through nurse-managed health clinics. Today there are about 250 such clinics in the United States, and “we hope there will be many more in the future,” said Hansen-Turton. These clinics are staffed by nurse practitioners, other advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, therapists and social workers, midwives, outreach workers, psychologists, collaborating physicians, health educators, students, administrative personnel, and other health professionals. They are located where people are—in shopping malls, in community centers, and sometimes in mobile vans. They generally offer low-cost, high-quality, community-based primary care and behavioral health, prenatal, and wellness services; some also offer dentistry and mental health services. About one-third are independent nonprofits, and two-thirds are affiliated with academic institutions, which enables these clinics to act as training sites for nurses and nursing students.

Approximately 46 percent of the patients seen at nurse-managed health clinics are uninsured, and 37 percent are on Medicaid. “You can’t sustain a business model on that unless you get grant funding, … so that is a challenge,” noted Hansen-Turton. However, the average primary care cost for these clinics is 10 percent less than for other types of providers, and the average personnel cost is 11 percent less than other providers’ costs. For patients who use these clinics, emergency room use, hospitalization, maternity days, specialty care costs, and prescription costs are all lower, she said. Yet nurse-managed health clinics see their members an average of 1.8 times more than other providers, and patients report high satisfaction with the care they receive at the clinics (Hansen-Turton et al., 2004).

Nurse-managed health clinics face a number of challenges, said Hansen-Turton. One is the patchwork of funding on which they rely—a combination of inconsistent reimbursement, federal dollars, and state and local funding. “The real issue is that the health care system has not quite caught up to the innovation of these clinics.” A recent national survey found that nearly half of all major managed care organizations do not credential or contract with nurse practitioners as primary care providers (Hansen-Turton et al., 2008). “That is going to be an issue if we want to avoid what is going on and what went on in Massachusetts when we get health insurance reform,” said Hansen-Turton.

The National Center on Quality Assurance (NCQA), which administers a certification program to recognize patient-centered medical homes, has said that its certification can be used only to accredit physician-led practices. Also, nurse practitioners cannot currently participate in some of the medical home initiatives supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Very recently, however, the Joint Commission, a nationwide accrediting body for health care organizations across a variety of settings, has approved certification for a primary care home that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants in leadership roles. Hansen-Turton said, “I think NCQA eventually will change, but it is important because certification is tied into reimbursement.”

Convenient Care Clinics

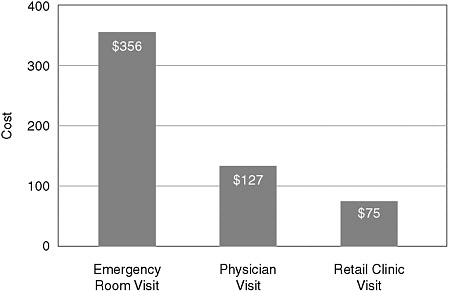

Another way to increase access to cost-effective care is through retail-based convenient care clinics, said Hansen-Turton, of which there are now about 1,200 in the United States. Services in these clinics are provided primarily by nurse practitioners, and no appointments are necessary. The clinics typically are located in retail outlets and have retail service hours, which generally extend beyond normal office hours for physicians. Pricing is transparent, with services typically costing between $40 and $75—significantly less than a visit to the emergency room or to a physician’s office; see Figure 4-1.

Hansen-Turton noted that the clinics generally accept insurance although about 35 percent of patients choose to pay out of pocket. Some of the insurance companies have embraced this model and have waived co-pays because they see it as a way to alleviate pressure on emergency rooms. The clinics use electronic health records and evidence-based medicine. Hansen-Turton said that she, her husband, and their son are typical users, having gone to such clinics about eight times in the past year. “We got immunized, we had a couple of strep throats, we had some ear infections, and we were in and out in about 30 minutes. It doesn’t get much better than that for those types of services,” said Hansen-Turton.

Research has supported the value of convenient care clinics. It has found that the care they provide is on a par with care from primary care physicians, urgent care centers, and emergency rooms in terms of quality and cost (Mehrotra et al., 2009). They are within a 10-minute drive for one-third of all Americans (Rudavsky et al., 2009), and they are

FIGURE 4-1 Comparison of costs associated with typical visits to the emergency room, physicians, and a retail clinic.

NOTE: “Typical visits” consisted of the three episodes that account for 48 percent of acute visits in retail-based convenient care clinics: otitis media, pharyngitis, and urinary tract infections.

effective in reaching the segment of the U.S. population that currently goes without regular care, with up to 60 percent of clinic patients not having a regular source of primary care (Mehrotra et al., 2008). “If you talk with any of the managed care organizations that contract with [the clinics], they’ll say that this is our lowest-cost health care option,” noted Hansen-Turton.

Nurse-Managed Health Clinics, Convenient Care Clinics, and Nurse Practitioners: Considerations for the Future

Hansen-Turton drew several suggestions from her overview of nurse-managed health clinics and convenient care clinics for the committee’s consideration. First, she noted that these clinics demonstrate the need to support new models that broaden access to quality care: “As everybody gets an insurance card, you are going to need places where you

can get care.” For this reason, Hansen-Turton said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should support medical home and performance-based demonstrations that include nurse-managed health clinics with nurse practitioners as primary care providers and convenient care clinics. Also, she said that managed care organizations and insurance companies should credential nurse practitioners as primary care providers, which would help to create an environment in which nurse practitioners and advanced practice nurses can perform all of the functions permitted under state scope-of-practice laws. Massachusetts took several of these steps after passing its health care reform legislation in 2007, and the laws passed there could be a model for states elsewhere (Craven and Ober, 2009).

In general, health care in the future will have a new focus on consumers. Hansen-Turton noted that young people in particular do not necessarily think of health care in the same way that older generations have. Customers who demand services that provide more value and are more affordable will catalyze disruptive innovations,1 and as Lee has stated, disruption needs to be seen as a virtue (Lee and Lansky, 2008). “Continuing to allow the perpetuation of the status quo will not improve Americans’ health status,” concluded Hansen-Turton.

THE INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE: A RURAL HEALTH CARE SERVICE

The Indian Health Service (IHS) employs more than 4,000 registered nurses, including more than 300 advanced practice nurses. It provides health care to 1.9 million American Indians and Alaska Natives around the country, mostly on reservations in rural and remote areas. Its system includes 48 hospitals; several hundred ambulatory, free-standing primary care clinics; and 34 urban clinics. Under Indian self-determination, about half of the service’s programs are now managed and operated by tribes themselves. Sandra Haldane, the chief nurse and director of the Division of Nursing at IHS, provided an overview of its accomplishments and bar-

riers to progress and offered the committee suggestions to convert challenges into achievements.

Most of IHS’s nurse practitioners are family nurse practitioners functioning as licensed independent practitioners under federal scope-of-practice guidelines. In the primary care setting, nurse practitioners have their own panels of patients, see a full load on a daily basis, and travel several times a week to satellite clinics and schools. They offer women’s health and midwifery services, pediatrics and well-child care, care for elders, and interventions for psychiatric and mental health conditions.

In recent years, the service has recognized that it is ill prepared and understaffed to deal with the high rates of sexual assault and domestic violence in the communities it serves. “In almost every instance, it has been nurse practitioners and nurse midwives who have taken on this issue,” said Haldane. They have become forensic experts and medical examiners and have worked with community partners to form programs so that people do not have to travel hours to get to private sector facilities for needed services. Haldane said that in the past 2 years, IHS has trained 60 forensic nurse examiners. Additionally, facilities have established programs to screen for sexually transmitted diseases, organized programs to facilitate mother-daughter interactions, and held faculty dinners at the high school and middle school levels to educate community leaders and youth on healthy lifestyles, behaviors, and risk factors.

IHS includes more than 350 public health nurses prepared at the bachelor’s level who are rarely found in clinics and hospitals but rather are out in the community. “They can be found making home visits to patients who have missed important appointments, checking on patients after discharges, or assisting with dressing changes in the home,” said Haldane. “They can be found assessing the safety of our elders’ homes, doing developmental testing of children at risk, going into reservation correctional facilities to provide screening and also into schools for health education, screening, well-child checks, and immunizations. They can be found at fitness centers, sports tournaments, concerts, and pulling over to the side of the road to visit with our Indian arts and crafts vendors to administer flu vaccine,” she said. This group of nurses is often the first to notice a change in disease patterns in the community that could indicate an infectious outbreak, as occurred recently when the public health nursing program at a facility in the southwestern region recognized a steady increase in gastrointestinal events as signaling an outbreak of salmonella.

Many advanced practice nurses and public health nurses in IHS have helped increase access to care and reduce disparities. Haldane described a program in Anchorage that was born out of a need to reduce the high rate of infant mortality in the native population there. All mothers were screened for risk factors, and those at risk were followed for a year, with nurses providing in-home education on growth and development, safety and nutrition education, immunizations, and referral to other community services. “The results have been outstanding,” said Haldane. Over a 5-year period the average number of days between infant deaths went from 55 to 130, the targeted population had decreased hospital admissions, the time between pregnancies increased, the use of emergency rooms fell, identified maltreatment declined, and more mothers appeared to be staying clean and sober.

Another example that Haldane cited is a reservation the size of Connecticut, on the border of Arizona and New Mexico, with 14,000 tribal members. In early 2007 the number of reported cases of syphilis increased dramatically to approximately three to five cases per month. Public health nurses worked with the tribe and parents to decrease the stigma of sexually transmitted diseases and get students to consent to screening. They developed culturally appropriate educational materials and took these materials into community centers and concerts. They conducted door-to-door campaigns to offer on-the-spot screening in a manner that would not embarrass tribal members or risk offense to tribal standards. The rate of new syphilis cases dropped significantly in 2008, and in the first part of 2009 there were no documented cases, said Haldane.

In some American Indian cultures it is not appropriate to talk about disasters, especially in the context of the future, so when a public health nurse on the Navajo Reservation began exploring ways to work with other preparedness entities, she had to do so without offending a very traditional people. “Through her insight and keen talent for relationship building, this public health nurse and her team developed a mass vaccination campaign to avert a disaster,” said Haldane. Community clinics were established and staffed with medical personnel as well as community volunteers so that they could work together to address threats in a community-based way.

Public health nurses must cover a broad spectrum of health concerns within the populations and communities they serve. Haldane observed that type 2 diabetes and obesity have become widespread, pressing problems among American Indian youth. In one community a public health

nurse who is also an avid soccer father worked to bring the American Youth Soccer Organization to the community, which gave Navajo children a fun and different physical activity they had not had access to previously.

Challenges for the Indian Health Service

Most IHS facilities are not rural; they are considered frontier,2 which brings a distinctive set of recruitment, retention, and practice challenges. The service’s vacancy rate for nurses in 2008 was 21 percent. In 2009, however, the vacancy rate decreased to 18 percent, perhaps because more nurses returned to the workforce as the economy weakened, said Haldane. Advanced practice nurses working within the IHS system still face some prejudice from physicians, who have a tendency to say that their patients are too complex for advanced practice nurses and more doctors need to be hired. Haldane also noted that more and more public health nursing programs are being cut because the majority of states do not reimburse services provided by public health nurses. IHS is authorized to spend only a certain amount on loan repayment for nurses, and advanced practice nurses have to compete with physician assistants for the same pool of loan repayment funds. “Thus, every year we end up with a significant number of advanced practice nurses who are matched to sites that qualify for loan repayment but do not get it because we run out of funds,” said Haldane.

The primary reason that 60 percent of the IHS’s registered nursing workforce is American Indian and Alaskan Native is because of a scholarship program available through IHS. However, of the hundreds of applications received each year, only about 100 students can be funded. For those who wish to go to school to achieve an advanced practice degree, opportunities are “dismal,” according to Haldane. The service’s system is seeing continuous decline in inpatient admissions and an increasing use of primary care and public health services, yet most new nurses’ education has focused on inpatient nursing. Indeed, some schools have dramatically curtailed their community and public health work because of

|

2 |

The Rural Assistance Center describes frontier areas as “the most rural settled places along the rural-urban continuum, with residents far from health care, schools, grocery stores, and other necessities. Frontier is often thought of in terms of population density and distance in minutes and miles to population centers and other resources, such as hospitals” (http://www.raconline.org/info_guides/frontier). |

student safety issues—thus producing students even less prepared for this type of work, said Haldane.

The population served by IHS tends to equate health care with physicians. “We struggle daily with how to educate our people on the advantages of advanced practice nurses,” said Haldane. “We struggle with awareness of what advanced practice nurses can do and with administrators who [mistakenly] believe that a nurse is a nurse is a nurse…. I can only speak for the Indian Health Service, but I doubt that these issues are exclusive to us,” said Haldane.

Despite the pressures of cost containment, it has to be possible to reimburse public health nursing activities such as going into high-risk homes to provide immunizations or to assess the growth and development of at-risk infants, said Haldane. Commissions, committees, and other entities tend to focus on health care that takes place in metropolitan and urban areas. More resources need to be focused on the health care system and the types of nurses it takes to provide access and quality to patients living in remote, rural, and frontier locations. About 1.2 percent of the U.S. population is American Indian or Alaskan Native. Yet only 0.1 percent of the nursing workforce is of that ethnicity, Haldane said. Programs that successfully recruit and retain American Indian and Alaskan Native nursing students will yield positive outcomes for patients.

Haldane also noted that under federal Office of Personnel Management rules, nurses are not always paid for being on call, and their overtime is capped. “They feel like they are providing unpaid volunteer service,” said Haldane. Changing payroll practices would help, but so would better reimbursement mechanisms so that additional staff could be hired to fill the need. Finally, the nursing profession must relentlessly educate the general public about the roles of advanced practice nurses, concluded Haldane.

RESPONSES TO QUESTIONS

A questioner asked whether retail care clinics actually save money or whether they treat health problems that might have been ignored if a clinic were not available. Hansen-Turton replied that retail clinics are not meant to be ongoing sources of primary care. However, they are designed to provide basic health care services, and emergency rooms are now being flooded with people needing attention for various types of basic health care issues that could be treated elsewhere. Since retail clin-

ics are available to everyone and are open during extended hours, they can provide access to basic continuity of care that may not be available to some people elsewhere in the health care system. “The task is designing a system in which all the pieces fit together smoothly. The real value proposition is multiple access to care, and certainly the retail clinics present a first level of care,” said Hansen-Turton.

In response to a question about how to increase the diversity of the nursing workforce and reduce barriers these candidates face in entering the nursing profession, Haldane said that many of the students who apply for scholarship programs through IHS are from remote and rural locations and are not as well prepared as other individuals. The service offers robust scholarship programs to assist qualified individuals, but it does not have enough funding for everyone who applies. Haldane also said that graduate students need adequate support and good mentors to transition from a student role into that of a fully functioning nurse.