Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI)

CTTI is a public–private partnership founded by FDA’s Office of Critical Path Programs and Duke University. The initiative, which includes stakeholders from government, industry, academia, patient advocacy groups, professional societies, and other organizations, has the goal of identifying practices whose broad adoption will increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials.9 In clinical trials, most of the costs are associated with human time and effort, so unnecessary complexity can be both burdensome and expensive. In the United States, where labor costs are higher than in other parts of the world, unnecessarily complex clinical trial processes can put the United States at a disadvantage.

NIH Roadmap for Medical Research

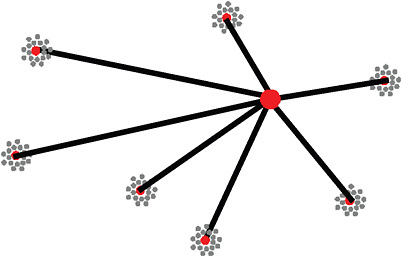

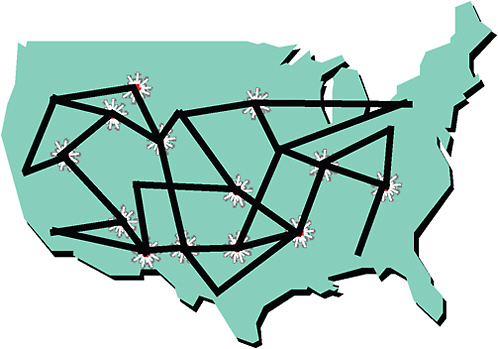

The NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, issued in 2003, set forth a vision for what the clinical research enterprise in the United States should look like. The Roadmap envisioned that in 10 years there would be a national clinical research system, based on electronic health records, in which all Americans would participate. Data in this system would be open and transparent. Robert Califf said that, although this vision has not yet been fully realized, many of the necessary components are being put in place. He suggested that avoiding additional layers of bureaucracy and focusing only on the core goals of clinical research would help create the system envisioned in the Roadmap. In contrast to the current model of a single coordinating center and a number of research sites conducting a clinical trial (Figure 8-2), existing networks would be linked using electronic health records and patient registries to create a more interconnected exchange of clinical research information (Figure 8-3).

International Examples

The United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and Australia are engaging in a similar dialogue on strategies to improve their clinical research infrastructure. According to Paul Hébert, the dialogue on the type of infrastructure needed to carry out clinical trials varies depending on the trial designs one wishes to use and the outcomes one seeks. In the United Kingdom, for example, large, pragmatic trials that have broad eligibility criteria and include a sizable number of patients are frequently used to test the effectiveness of drugs or medical interventions. Data collection in such trials is usually

|

9 |

Additional information on the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) can be found at https://www.trialstransformation.org/. |

FIGURE 8-2 Typical NIH clinical trial network with academic health center sites surrounding the hub of a data coordinating center.

SOURCE: Califf, 2009. Reprinted with permission from Robert Califf 2010.

FIGURE 8-3 A vision of an integrated clinical research system linking existing networks (patients, physicians, and scientists) to form communities of research and conduct clinical trials more effectively.

SOURCE: Califf, 2009. Reprinted with permission from Robert Califf 2010.

minimal (two to three pages), compared with other trial designs that involve the collection of multiple binders of data.

Hébert explained that in the United Kingdom, national clinical research networks exist on six major themes, and each includes 7 to 10 local clinical investigator networks. The local networks serve primarily as recruiting centers for large, national trials. To support this system, the British government initiated a realignment of research funding so that it is coordinated centrally and provided nationally.

In a discussion of patient registries, Christopher Cannon echoed the sentiment that the goal of clinical research—the outcomes sought—should shape the way a research infrastructure is built. Although the confounding that characterizes registries (why an individual received one therapy versus another) makes it impossible to use these data to compare different therapies, Cannon suggested that patient registries could provide the data collection infrastructure for a system of large, pragmatic trials. For instance, as health information technology advances, the passive collection of data becomes easier. A simple randomization of therapies in a broad population (e.g., the Medicare population), with data being collected inexpensively, could provide the infrastructure necessary to conduct more large, simple trials in the United States, similar to those popular in the United Kingdom.

International agencies and governments are also grappling with ways to overcome the barriers to clinical research. Hébert shared the results of a survey of U.S. and European companies indicating that the process of negotiating contracts for clinical research is a major burden in terms of both time and cost. While collaborations can be useful for generating new research, the contract and negotiation process across multiple entities can be extremely difficult. For instance, the development of contracts for a large, multisite, international trial that requires funding from a number of different collaborators requires a significant amount of time and money—Hébert estimated the process can take 2 years.

Hébert also cited current efforts to improve clinical research in Canada. These efforts include investing in the workforce (e.g., biostatisticians, health economists, and epidemiologists), using the flexibility and support functions of 89 large national networks already in existence, and integrating research into clinical practice through the development of 20 to 30 support units across the country.

The health care system largely drives the way in which clinical research is conducted, according to Hébert. The United Kingdom and Canada, for instance, have single-payer systems that facilitate centralized control of the clinical research enterprise. Hébert suggested that the United States can learn from the experiences of other countries but that ultimately, the solution to improving its clinical research enterprise will need to be tailored to the U.S. context and take into account the unique driving forces (i.e., the

health care system, political perception and motivation of decision makers) behind any systemic change.

LARGE, SIMPLE CLINICAL TRIALS

The NCI and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) are cofunding a large, simple trial on the effects of vitamin D. Called the VITAL trial, it will enroll 10,000 men over age 60 and 10,000 women over age 65, who will receive daily high doses of oral vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids.10 The goal of the trial is to determine whether vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids lower the risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer. The trial will cost $150 per participant and take place over 5 years.

Because the VITAL trial involves a low-risk, preventive intervention in a primarily healthy population, it offers the opportunity to implement a unique and efficient trial methodology that bypasses the physician and works directly with the study participants. In the VITAL trial, study forms and pills are mailed directly to patients, and no clinic visits are necessary. Michael Lauer described the VITAL trial design as similar to that of the Physicians’ Health Study, in which investigators rather than practicing physicians communicate with study participants. This design can facilitate recruitment of study subjects—an important consideration for a trial that seeks to enroll thousands of patients for a low overall cost. The Internet has been an especially useful tool for trials that require such direct communication with patients. Recruiting patients, communicating study details, and collecting data via the Internet will likely become increasingly useful for conducting clinical trials, according to Lauer.

Amir Kalali referred to iguard.org, a Web-based tool that can aid in the recruitment of patients for trials. Created in 2007 and funded by Quintiles, this website allows patients, providers, and caregivers to monitor the safety of medications. Individuals can enter the medications they are taking and receive any alerts from the FDA on those medications. In addition, if an individual takes multiple prescriptions, the service will provide an alert as to any medication interactions. Kalali explained that he believes iguard. org has attracted millions of subscribers because it offers information not provided by doctors. In addition to answering questions about medications, iguard.org asks patients whether they are interested in participating in clinical research. Kalali noted that this Web-based method of finding patients for trials has been particularly useful for conducting the type of large, simple trial that bypasses interaction with physicians and relies on direct communication with patients.

|

10 |

Additional information on the VITAL trial can be found at www.vitalstudy.org. |

SUGGESTIONS FROM THE BREAKOUT SESSIONS

On the second day of the workshop, small groups were formed around each of the four disease areas (cardiovascular disease, depression, cancer, and diabetes). Each group was asked to:

-

describe a concise vision of clinical research within its disease area that would better support the goal of a learning health care system;

-

identify the gap between this vision and current practices;

-

identify best practices (from any disease area) or untested but potentially powerful approaches to organizing clinical trials that could address this gap; and

-

identify the key impediments to implementing such approaches that would have to be addressed for the vision to be realized, such as infrastructure, public–private investment, workforce, legal and institutional constraints, academic culture, and traditions.

Following the discussions, the breakout chairs reported the groups’ findings to the larger workshop audience.

Cardiovascular Disease Breakout Session

Discussion in this breakout session focused largely on strategies and policies that could lead to the creation of a national clinical research network positioned to accelerate research efforts in all disease areas. The group suggested that a national network could be based in the primary care setting but should go beyond physicians to include the full spectrum of the primary care workforce. The group discussed components of such a network that might already be in place today. An example is the 46, soon to be 60, CTSA institutions that encompass much of academic medicine in the United States. In addition, 52 Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) comprise groups of primary care practices throughout the country. Historically, PBRNs have been underfunded, but the fact that physicians have joined these networks without the promise of core funding indicates that there is significant interest among practicing community-based clinicians in developing clinical questions and producing research results that can effectively improve everyday clinical practice.

Patient advocacy and voluntary health organizations would have an important role in driving the effort to build a national research network. Groups with experience in using social networking and other outreach mechanisms could be highly effective in engaging the public and building broad interest in clinical research.

NIH and industry, as the key sponsors of clinical research in the United States, also have an interest in building a national research network that would improve the efficiency of clinical trials, with the overarching goal of answering more of the most important research questions.

Several key barriers to creating a more efficient clinical research enterprise were discussed in the breakout session:

-

ethics review—delays and difficulties encountered in obtaining approval for a clinical trial protocol;

-

contract negotiations—contentiousness and delays surrounding the contract negotiation process between NIH and clinical trial sites; and

-

intellectual property—agreements that include requirements that human subjects research results be kept confidential for 5 years. (It was suggested by discussants that they believed that beyond phase II research, intellectual property should not be a contentious issue in the academic arena.)

Depression Breakout Session

This breakout session formulated a broad vision for future research efforts in depression that included successfully treating the disease in all forms and settings, with a goal of achieving remission for 60 percent of patients. The development of sensitive research tools and measures of depression that would accurately convey the state of the disease could improve the development of informative clinical trials. Similar to a point made in the diabetes session, a 100-year goal for depression could be preventing the onset of the disease.

Creating unified standards for every human measure and the data systems to manage them would help in ensuring that the significant investment each human subject confers in agreeing to participate in a clinical trial results in the highest possible value to the clinical trial enterprise. Involving patients and patient advocates throughout the trial design and implementation process would also help improve clinical trials and the validity of the results they generate. Expanding clinical trial design toolkits and increasing the number of depression studies that examine long-term outcomes would also be useful.

The group also discussed the idea of including research in the routine delivery of care so as to remove the current divide between the clinical research enterprise and clinical practice. Integrating these two worlds would require new models to better align research and health care delivery as well as culture change at all levels (e.g., patients, providers, educators, and legislators). To facilitate culture change, large outcome studies that answer

important questions could be used to engage stakeholders and gain public trust and involvement.

Cancer Breakout Session

Meeting patients’ expectations of the clinical research enterprise was the focus of this group’s discussion. Patients should expect that their treatment is evidence-based and that their treatment experience will form the basis for an increase in knowledge, which in turn will lead to improvement in their care. In such a learning health care system, physicians, nurses, data managers, payers, patients, and regulators would all contribute to the process by which health care outcomes would inform clinical practice.

Numerous gaps exist between the current health care system and the ultimate goal of a learning health care system. The group discussed, for instance, the need to correct public misconceptions about clinical trials and the overall value of clinical research. For practitioners, the progression through the core curriculum of medical school and eventually continuing medical education includes limited instruction in conducting clinical research. In addition, misaligned incentives exist in a reimbursement system based on the volume of patient visits or procedures completed. Another important gap is the lack of coordination and prioritization of clinical trial research questions. These and other barriers discussed in Chapter 3 characterize the inadequate research infrastructure that exists at every level of the health care system. The group also highlighted significant gaps in the instruments used to analyze issues surrounding end of life and quality of life.

While the above gaps are substantial, the group discussed four areas of oncology that have exhibited best practices in clinical research:

-

Pediatric oncology—Based on a relatively small network of practicing pediatric oncologists, this area of medicine has created a culture shift in which oncologists in training have mentors and role models in the field to further the circulation of clinical information. The majority of practitioners are salaried, which removes the traditional focus on performing a high volume of procedures. In addition, the field of pediatric clinical oncology includes significant patient and family involvement, enhancing the flow of information throughout the network and overall public investment into this area of clinical research and practice. Many children with cancer have been enrolled in clinical trials, which have resulted in significant advances in cancer treatment and patient health.

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)—In these two areas, patients have largely instigated the

-

sharing of information on clinical research and the use of effective treatments for these conditions.

-

Multiple myeloma and prostate cancer—The advocacy community has assumed significant responsibilities for financing research and clinical trials in these two areas, thus creating an alternative and more flexible structure than the NIH funding system.

-

Breast cancer—Advocacy collaborations between patients and researchers have influenced federal legislation and the allocation of additional funding to clinical research.

The group also discussed how payers would benefit from supporting and financing clinical trials in that they could be the first to demand the most effective, evidence-based treatments. In the case of solid tumor transplantation, for example, payers are already demanding fast screening, whereas the FDA has yet to improve the test for this type of screening. Putting payers on the cutting edge of clinical research could be a powerful approach to advancing clinical practice.

During the discussion, it was noted that, to accelerate clinical research and improve the infrastructure underlying clinical trials, leadership and coordination from the highest levels of government would be necessary. A caution was expressed, however, that the bureaucratization of clinical research should be avoided—care should be taken when considering the creation of new structures and the accompanying regulatory and legal constraints.

Finally, discussion focused on the need to build a sufficient clinical research workforce. An important step in this direction would be to improve the academic culture such that clinical investigation is widely viewed as a legitimate academic pursuit.

Diabetes Breakout Session

This group’s discussion focused primarily on how the clinical research system can meet the needs and expectations of patients. Patients should be empowered and provided access to the clinical research enterprise. Voluntary health organizations such as the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) could be instrumental not only in improving patient awareness of clinical trial opportunities, but perhaps more importantly, in helping individuals understand the role of clinical research in improving health care.

In addition, the clinical research enterprise should be founded on the enthusiasm of providers. To create such a system, clinical investigators and academic leaders should be rewarded, not just financially, for their efforts in clinical research. In addition, trust in the clinical research system needs to

be restored and skepticism regarding associations with the pharmaceutical industry needs to be reduced.

The discussion identified the prioritization of clinical research needs as the main challenge to any new clinical research system. A key question is who will decide which areas of disease research will receive resources.

Finally, the group acknowledged that information technology holds great promise for long-term improvement in the way clinical research is conducted. However, revamping the regulatory and ethical foundations of clinical research is essential in the short term.

TRANSFORMING CLINICAL RESEARCH

In light of the presentations and discussions regarding the significant challenges facing clinical research in the United States today, Janet Woodcock shared her vision for a transformed clinical research enterprise. While many individual aspects of the clinical trial process could be enhanced, she focused on the need for a transformational change in the way clinical research is conducted. She described a vision of a clinical research infrastructure in the United States akin to the national highway system or the national energy grid—in other words, a large public works project designed to ensure that patients, clinicians, and academic researchers all have access to a system that links research and community practice, and facilitates universal participation in the generation of new clinical evidence and its subsequent adoption by physicians.

In Woodcock’s vision, a permanent network of resources (e.g., research sites, investigators, and support staff) would be available to anyone conducting scientific inquiries in health care. As opposed to the ad hoc manner in which clinical trials are conducted today, this network of resources would be continuously funded and permanent. The investigators that are part of this network would be organized regionally or nationally around disease or practice areas, or “nodes.” This structure would allow the network to address questions ranging from health care delivery (e.g., psychiatrists vs. clinical psychologists in various care settings) to the appropriate medical intervention (e.g., antidepressants vs. talk therapy). The required features of the research network would include community trust and involvement (patients and practitioners), high quality and sufficient quantity of research conducted, and demonstrated efficiency in conducting clinical research (rapid trial implementation and patient enrollment).

Supporting and uniting the investigators would be core clinical trial and disease experts with dedicated time to support, run, and organize the clinical research infrastructure. These experts would likely be academics because of their engagement in the scholarly study of disease and clinical trial methodology. Core research personnel would also form the backbone

of this cadre of experts. Regulatory experts to guide a study through the IRB process, data managers, biostatisticians, and administrative personnel would be available so that investigators would not need to reinvent the wheel for each study. The network of resources could be utilized by single investigators, academic groups, foundations, or industry for a fee and based on mutual agreement between the network and the research sponsor.

The clinical research infrastructure would be supported through continuous federal funding for the research network and the cadre of experts around the country. The basic funding mechanism would be contracts, not grants, because, according to Woodcock, the episodic nature of grant proposals is not ideal for building infrastructure. Woodcock elaborated on this key feature of her vision by hypothesizing that if grants had been used to build the highway system or energy grid in the United States, we would not have the successful infrastructures we have today.

Workshop participants discussed the many potential benefits of implementing such a vision and the transformational change it would introduce to the clinical research enterprise in the United States. Currently, industry-sponsored clinical trials entail the recruitment of individual investigators and the ad hoc creation of a trial infrastructure around the selected investigators. Under Woodcock’s vision, a core set of trial experts would engage in a collective decision-making process regarding whether to accept a research proposal. Thus, Woodcock suggested, her vision could create a structural distance between industry-sponsored trials and investigators. This separation could have a positive effect on the general public’s trust in clinical research. Peter Honig, Head of Global Regulatory Affairs, AstraZeneca, referenced a Harris poll finding that 68 percent of the American public recognizes that clinical research has substantial value, while 42 percent of Americans distrust pharmaceutical companies. In light of these data, reducing the intensity and directness of relationships between industry and investigators could improve public trust in clinical research and redress the mismatch between the public’s perception of the value of clinical research and its distrust in how the research is conducted.

In discussing the strengths and weaknesses of Woodcock’s proposal, Steven Kahn stressed the importance of having a strong, universal health care system as the backbone for such a vision—something the United States lacks. Workshop participants echoed the sentiment that adding a layer of infrastructure for clinical research to the fragmented health care system in the United States would be difficult and potentially ineffective. Participants also raised the question of who would pay for a permanently funded clinical research infrastructure. Califf suggested that the flow of research jobs abroad could provide significant motivation for a broad coalition of federal agencies to support this domestic initiative. Woodcock added that current approaches to studying health care will not deliver the amount or quality of

information needed. The U.S. Congress and federal agencies administering health programs throughout the country constantly ask which health care products and procedures to pay for (i.e., what is reasonable and necessary) or how to structure benefits and services. However, the clinical trials needed to answer these questions cost millions of dollars each and require years of development and implementation. While the United States currently lacks the capacity to examine the large number of research questions that must be answered to form the foundation of a learning health care system, Woodcock’s vision for a permanent, continuously funded clinical research infrastructure is one possible strategy for improving clinical research capacity in the United States.

References

Alving, B. 2009. The Role of CTSAs in Transforming the Clinical Trials Process in the United States. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Califf, R. M. 2009. ACS and Acute Heart Failure Models. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Di Masi, J. A., R. W. Hansen, and H. G. Grabowski. 2003. The price of innovation: New estimates of drug development costs. Journal of Health Economics 22(2):151–1185

Dilts, D. M., A. Sandler, S. Cheng, J. Crites, L. Ferranti, A. Wu, R. Gray, J. MacDonald, D. Marinucci, and R. Comis. 2008. Development of clinical trials in a cooperative group setting: The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Clinical Cancer Research 14(11):3427–3433.

Dilts, D. M., A. B. Sandler, S. K. Cheng, J. S. Crites, L. B. Ferranti, A. Y. Wu, S. Finnigan, S. Friedman, M. Mooney, and J. Abrams. 2009. Steps and time to process clinical trials at the cancer therapy evaluation program. Journal of Clinical Oncology 27(11): 1761–1766.

Durivage, H. J., and K. D. Bridges. 2009. Clinical trial metrics: Protocol performance and resource utilization from 14 cancer centers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 27:15s (abstract 6557).

Fava, M., A. J. Rush, S. R. Wisniewski, A. A. Nierenberg, J. E. Alpert, P. J. McGrath, M. E. Thase, D. Warden, M. M. Biggs, J. F. Luther, G. Niederehe, L. Ritz, and M. H. Trivedi for the STAR*D Study Team. 2006. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry 163(7):1161–1172.

Glickman, S. W., J. G. McHutchison, E. D. Peterson, C. B. Cairns, R. A. Harrington, R. M. Califf, and K. A. Schulman. 2009. ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine 360:816–823.

Greenbaum, C. 2009. Recruitment and Regulation … the Twin Headaches of Clinical Trials. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001a. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001b. Preserving Public Trust: Accreditation and Human Research Participant Protection Programs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2002. The Role of Purchasers and Payers in the Clinical Research Enterprise: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Learning What Works Best: The Nation’s Need for Evidence on Comparative Effectiveness in Health Care. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/VSRT/ComparativeEffectivenessWhitePaperF.ashx (accessed January 12, 2010).

IOM. 2008. Improving the Quality of Cancer Clinical Trials: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

IOM. 2009a. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009b. Multi-Center Phase III Clinical Trials and NCI Cooperative Groups. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009c. Addressing the Threat of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009d. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Value in Health Care: Accounting for Cost, Quality, Safety, Outcomes, and Innovation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kahn, S. E. 2009. Clinical Trials in Type 2 Diabetes: Structure, Function, and Outcome Relationships. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Kessler, R. C., P. A. Berglund, O. Demler, R. Jin, and E. E. Walters. 2005. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6):593–602.

Krall, R. L. 2009. U.S. Clinical Research. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Lane, H. C. 2009. Improving the Effectiveness and Efficiency of NIH Intramural Clinical Research. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Lauer, M. S. 2009. Clinical Research in Acute and Chronic Life Threatening Conditions: A Government Perspective. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Lilford, R. J., and J. Jackson. 1995. Equipoise and the ethics of randomization. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 88:552–559.

McGlynn, E. A., S. M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey, J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, and E. A. Kerr. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635–2645.

McGrath, P. J., J. W. Stewart, M. Fava, M. H. Trivedi, S. R. Wisniewski, A. A. Nierenberg, M. E. Thase, L. Davis, M. M. Biggs, K. Shores-Wilson, J. F. Luther, G. Niederehe, D. Warden, and A. J. Rush for the STAR*D Study Team. 2006. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1531–1541.

Mills, E. J., D. Seely, B. Rachlis, L. Griffith, P. Wu, K. Wilson, P. Ellis, and J. R. Wright. 2006. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncology 7(2):141–148.

NASMHPD (National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors), Medical Directors Council. 2006. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/med_directors_pubs/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08.pdf (accessed June 24, 2010).

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2010. Fact Sheet: Cancer Clinical Trials. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Information/clinical-trials (accessed June 16, 2010).

NCRR (National Center for Research Resources) [unpublished]. 2006. NIH Roadmap Re-Engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise: Inventory and Evaluation of Clinical Research Networks (IECRN): Complete Project Report. Washington, DC: NIH.

NDIC (National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse). 2008. Diabetes Overview. http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/overview/ (accessed June 28, 2010).

Nierenberg, A.A., M. Fava, M. H. Trivedi, S. R. Wisniewski, M. E. Thase, P. J. McGrath, J. E. Alpert, D. Warden, J. F. Luther, G. Niederehe, B. Lebowitz, K. Shores-Wilson, and A. J. Rush. 2006. A comparison of Lithium and T3 augmentation following two failed treatments for depression: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1519–1530.

Peterson, E. D., M. T. Roe, B. L. Lytle, L. K. Newby, E. S. Fraulo, W. B. Gibler, and E. M. Ohman. 2004. The association between care and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome: National results from CRUSADE. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 43(Suppl 2):406A.

Rush, A. J., M. H. Trivedi, S. R. Wisniewski, J. W. Stewart, A. A. Nierenberg, M. E. Thase, L. Ritz, M. M. Biggs, D. Warden, J. F. Luther, K. Shores-Wilson, G. Niederehe, and M. Fava for the STAR*D Study Team. 2006. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. New England Journal of Medicine 354(12):1231–1242.

Trivedi, M. H. 2009. Models of Clinical Research in Depression: Lessons Learned from STAR*D. Speaker presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Transforming Clinical Research in the United States, October 7–8, 2009, Washington, DC.

Trivedi, M. H., M. Fava, S. R. Wisniewski, M. E. Thase, F. Quitkin, D. Warden, L. Ritz, A. A. Nierenberg, B. Lebowitz, M. M. Biggs, J. F. Luther, K. Shores-Wilson, and A. J. Rush for the STAR*D Study Team. 2006a. Medication augmentation after failure of SSRIs for depression. New England Journal of Medicine 354(12):1243–1251.

Trivedi, M. H., A. J. Rush, S. R. Wisniewski, A. Nierenberg, D. Warden, L. Ritz, G. Norquist, R. H. Howland, B. Lebowitz, P. J. McGrath, K. Shores-Wilson, M. M. Biggs, G. K. Balasubramani, and M. Fava for the STAR*D Study Team. 2006b. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:28–40.

Walsh, T. B., S. N. Seidman, R. Sysko, and M. Gould. 2002. Placebo response in studies of major depression: Variable, substantial, and growing. Journal of the American Medical Association 287(14):1840–1841.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Table A2: Burden of Disease in DALYs by Cause, Sex and Income Group in WHO Regions, Estimates for 2004. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2008. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_AnnexA.pdf (accessed June 14, 2010).

WHO. 2004. The World Health Report 2004: Changing History. Annex Table 3: Burden of Disease in DALYs by Cause, Sex, and Mortality Stratum in WHO Regions, Estimates for 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.