3

Supporting Preschool Language for School Learning

The second workshop session reviewed research on early language experiences with an emphasis on practices in preschool classrooms and aspects of early childhood interventions that contribute to developing the language proficiencies associated with academic learning and that could be especially important for closing achievement gaps. Of particular interest were the following questions: Which aspects of early preschool language affect later reading and academic achievement? Do language differences associated with socioeconomic status (SES), race, ethnicity, and home language affect reading and academic achievement outcomes for preschoolers, and if so, how can these differences be explained? What interventions show signs of being effective in helping preschoolers develop aspects of language that predict reading comprehension and academic achievement? With respect to young English-language learners, the session focused on the relation between first- and second-language development in the preschool years, and linkages between first-and second-language development and children’s early literacy skills. Participants were asked to discuss the implications of this research for designing practices to develop children’s second-language and early literacy proficiencies, especially in classroom settings.

A DEVELOPMENTAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

Two aspects of preschool language—receptive and expressive vocabulary and comprehension and use of complex sentences and discourse—

predict later reading and other literacy skills, David Dickinson reported. For instance, several studies and a recent meta-analyses conducted by the National Early Literacy Panel (2008) have reported long-term relationships between aspects of vocabulary in early childhood and measures of reading comprehension in middle school and high school (see Dickinson and Freiberg, 2009). Beyond vocabulary, length of utterances and diversity of words at age 3 has predicted language, spelling, and reading skills in kindergarten and 3rd grade after controlling for SES and school attended (Walker et al., 1994). Similarly, a longitudinal study of 626 children from low-income homes showed that oral language at age 4 predicted reading comprehension in 3rd and 4th grade (Storch and Whitehurst, 2002). The National Early Reading Panel (2008) also recently reported from a meta-analysis that although expressive and productive vocabulary predicted reading comprehension, several measures of complex language, such as complexity of grammar, were better predictors.

Dickinson turned next to studies documenting group differences in language and achievement associated with SES, race, ethnicity, and home language. Such group differences emerge early and only increase with age (see Dickinson and Freiberg, 2009). Early language differences have been documented for each of these groups in nationally representative samples including research on Head Start (FACES, 2006), the Early Child Care Study (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2003), and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (Chernoff et al., 2007). In addition, recent data collected by Dickinson and Ann Keiser at Vanderbilt University with 440 African American children in a Head Start program showed that standard measures of expressive and receptive vocabulary and broader language skills were all about one standard deviation below national norms for all children in the United States. Likewise, as mentioned earlier by Hoff, individual differences in language processing speed begin early, affect language learning, and are associated with poverty. More specifically, Anne Fernald and her colleagues (e.g., Fernald, Perfors, and Marchman, 2006) have shown that the speed of children’s lexical access at 12-25 months correlates with parents’ reports of children’s vocabulary size and complexity of language use at 25 months. Children’s rate of productive vocabulary growth also correlates with speed of lexical processing. In other research, Maria Vasilyeva and colleagues (2006) examined the use of complex syntax in relation to SES: they found that, at 22 months, all children used complex syntax at least some times, showing the potential to develop language complexity. However, by 42 months, the number of complex sentences used by children with low SES, while increasing, was much lower than the number used by more advantaged children (Vasilyeva, Huttenlocher, and Waterfall, 2006; Vasilyeva, Waterfall, and

Huttenlocher, 2008). Small SES-related differences in the complexity of language grow larger over time.

Findings such as these support the notion that all children come into the world ready to learn language, and, depending on how much language they hear, they become better and better at processing language. These data reflect more than biologically dictated trajectories in processing speed, Dickinson noted, because poverty, an environmental variable, is associated with variations in language input that are in turn associated with early differences in processing speed. Some of the most powerful findings from Hart and Risley (1995), he said, which tend not to be widely cited, also illustrate the power of early environments on the trajectory of children’s vocabulary growth. Between 30 and 36 months the most advantaged children in their research gained 350 words, about half again as many as they knew at 30 months. Children from the lowest income backgrounds, despite having fewer words, also learned about half again as many words as they knew at 30 months. But given where the second group started and the nature of the linguistic input they continued to experience, they did not develop vocabulary to their full potential.

These early language differences associated with SES have implications for early reading. Christopher Lonigan and colleagues examined phonological awareness, a linguistic skill which predicts later reading, and found that, in contrast to children from middle-income homes, children entering kindergarten from lower income backgrounds had not progressed beyond the scores obtained as 3-year-olds, and so they were not as ready to engage with the kindergarten curriculum.

What accounts for differences in language learning associated with demographic variables? Dickinson argued the differences result from both the quantity and quality of language that children experience both inside and outside their homes. With respect to home experiences, many studies have found that frequency of book reading affects language learning (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008), as well as access to verbally active adults who engage children in conversation and given them access to the definitions of words (Hart and Risley, 1995; Weizman and Snow, 2001; Hoff, 2009; Zimmerman et al., 2009).

Next, Dickinson turned to research showing that preschool classroom experiences also affect language learning. New longitudinal research by Dickinson and Porche (not yet published) showed that language experiences in preschool classrooms at age 4 predicted receptive vocabulary in kindergarten, which in turn predicted receptive vocabulary at the end of 4th grade, accounting for 60 percent of the variance in 4th grade vocabulary scores. Similarly, language experiences in preschool classrooms accounted for 47 percent of the variance in 4th grade reading comprehension. More specifically, an indirect effect was evident in which preschool

classroom language experiences at age 4 predicted kindergarten vocabulary and print knowledge, which in turn predicted 4th grade reading comprehension.

Despite the importance of a child’s early linguistic environment for later reading achievement, the support provided for language learning in preschool classrooms serving children from low-income backgrounds is frequently very weak. In one study of teacher and child talk with a sample of 16 classrooms, Dickinson found that for those classrooms ranking in the top quartile of talk, teachers expressed 1,208 utterances and children expressed 434. For classrooms in the bottom quartile, teachers provided 450 utterances and children provided 70. It is not yet clear how these differences will relate to children’s later language, reading, and school achievement, he noted, but dramatic differences such as these are likely to affect such outcomes.

Interventions are needed to make teachers aware of their own language usage and ways to support children’s language. To help researchers and teachers understand more about the preschool environments that children experience, better tools would need to be developed, ideally with the involvement of language experts, for assessing uses of language in classroom environments. Current measures of preschool classroom quality are very global and do not attend sufficiently to the linguistic aspects of classrooms.

What approaches to early childhood intervention are likely to support preschoolers’ language? Broad interventions, such as public pre-kindergarten programs, have had some success (see Dickinson and Freiberg, 2009). Public pre-K programs with positive language outcomes tended to have several elements: teachers with relatively high salaries and more education, training and coaching support; better-than-average oversight and resources; and a strong curriculum designed to target language. Quality of delivery also matters. Interventions delivered by researchers may not be able to come to scale without significant support.

Parent-focused interventions also show promising results. The National Early Literacy Panel (2008) reported rather small but significant effects of parent-focused interventions on overall language and vocabulary, with stronger effects from birth to age 3. In addition, community-based programs that focused on book reading and were delivered through pediatricians have shown positive outcomes.

Dickinson concluded with suggestions for early language-learning research in four categories (elaborated further in Dickinson and Freiberg, 2009):

-

descriptions of early childhood classroom language environments, including the factors that constrain and promote certain types and patterns of language use;

-

language learning, including research to identify the range of linguistic supports needed at different points in development and to indicate how much growth is possible at different ages;

-

teaching and learning, which includes research to identify preschool classroom configurations (small groups and large groups), activities, and practices that support language learning and how the outcomes vary according to age and other characteristics of children; and

-

intervening, or research that translates the above knowledge into effective and sustainable instructional approaches.

YOUNG DUAL-LANGUAGE LEARNERS

Carol Scheffner Hammer reviewed research on the language development of dual-language learners during preschool and on linkages to reading development in kindergarten and 1st grade. She defined dual-language learners as preschool-age children who have been learning Spanish and English simultaneously since birth or who began learning the second language with the onset of schooling.

With respect to the early language of bilingual infants and toddlers, it is known that development is similar to that of monolinguals: for instance, bilinguals say their first words, begin producing phrases, and start expressing themselves through sentences at the same time that monolingual children do. Vocabulary size, with both languages combined, is comparable to that of monolingual children. Developmental pathways can diverge, however: one example is differences in the order in which bilingual and monolingual children acquire grammatical morphemes.

Despite their increasing numbers in U.S. schools, little research has documented the language experiences of dual-language preschoolers and how those experiences affect subsequent language growth, literacy development, and school achievement. Instead, the research on preschoolers has focused quite narrowly on children from low-income, Spanish-speaking backgrounds, and it primarily includes children who attended English immersion classes because that type of approach is the most widely available. Studies of preschoolers to date show that scores on measures of English vocabulary and English auditory comprehension for Spanish-speaking children who are dual-language learners from low-income households tend to fall one to two standard deviations below monolingual norms in both languages at the beginning of preschool (see Hammer, 2009). Though gains are usually made during the preschool years, children typically finish preschool with scores that remain below monolingual norms in each language. Likewise, studies that have measured early literacy outcomes for young dual-language learners find that

children both enter and finish preschool with early literacy skills that are within one standard deviation below monolingual norms (see Hammer, 2009, for a review).

Because research has focused on children from families with low incomes, the findings just noted may be due to SES-related factors. More generally, bilingual children tend to be studied as if they are a monolithic group. Many individual differences potentially affect children’s outcomes, and so it is difficult to draw strong conclusions about language learning from existing data. Several researchers (including Hammer) have argued, for instance, that two important individual differences that affect learning may be the timing of exposure to the second language and the degree of second-language proficiency at school entry.

For instance, data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort shows that differences in the early reading development of dual-language learners depend on whether or not children were proficient in English when they entered kindergarten (Kieffer, 2008). Children who were proficient in English at the beginning of kindergarten demonstrated reading trajectories that were similar to monolingual English speakers. Children who were not proficient in English at the beginning of kindergarten had developmental trajectories that were lower than proficient speakers, with the differences increasing over time, though the effect of initial English proficiency on children’s reading trajectories was attenuated after controlling for socioeconomic factors.

Only a few studies have explored how exposure to English versus Spanish at home before kindergarten might affect the trajectory of language and literacy learning for Spanish-speaking children in the early grades (see Hammer, 2009). Hammer reported on longitudinal research designed to examine this question for children from Spanish-speaking homes who attended an English immersion Head Start program for 2 years. Some of the preschoolers came from homes that communicated in Spanish and English before the children entered Head Start and other children came from homes that used only Spanish. Children’s performance was documented using standardized measures of language and literacy in both English and Spanish that were normed on monolingual speakers. Hammer cautioned, however, that dual-language learners should not be expected to perform like monolingual children because the linguistic experiences of monolingual speakers and dual-language learners differ. Ideally tests standardized on bilingual populations should be used to examine dual-language learners’ development. However, tests standardized on dual-language populations did not exist at the time the study was conducted.

At the beginning of the Head Start program, both the English- and Spanish-language scores for all the dual-language learners were signifi-

cantly lower than monolingual norms, as might be expected for a low-income sample. After attending the English immersion Head Start program for 2 years and kindergarten, children’s receptive vocabulary increased to within one standard deviation of standardized English monolingual norms for their age group, and their auditory comprehension was at the standardized monolingual mean. Spanish-language scores, however, did not keep up with Spanish monolingual norms, which could be the result of attending an English immersion preschool, Hammer said. English and Spanish vocabulary grew faster, however, for children from homes that did not communicate in English.

With respect to literacy, all children experienced small increases in their English and Spanish letter knowledge, phonological awareness, and other emergent literacy skills after 2 years of attending the Head Start program. Moreover, in kindergarten and 1st grade, all the children continued to make substantial gains in English phonological awareness and letter-word knowledge and either met or exceeded the English monolingual norms. At 1st grade, English reading comprehension was also above the monolingual norm for all children.

Spanish literacy, however, showed some declines after the Head Start English immersion program. Children’s Spanish phonological awareness and letter knowledge increased through kindergarten but their Spanish letter-word identification and reading comprehension were not as strong as their English abilities in these areas in the early elementary grades. Decreases in Spanish literacy skills continued as children progressed through 2nd grade, with children from homes in which English was spoken scoring nearly three standard deviations below Spanish monolingual norms.

Next Hammer described relationships that were observed between home language usage and children’s language and emergent literacy development. Mothers’ use of Spanish at home did not affect growth in English vocabulary or English early literacy skills, but it was associated with Spanish vocabulary growth. Perhaps surprisingly, continued use of English at home was not associated with growth in English vocabulary, though it did appear to slow Spanish vocabulary growth. Hammer speculated that children’s exposure to English in their communities and schools reached a threshold beyond which home use of English did not measurably hinder or promote English vocabulary growth, while home use of Spanish gave children critical exposure not received elsewhere.

Additionally, Hammer discussed relationships between language growth during Head Start and children’s reading outcomes in early grades. Findings showed that growth in Spanish language (as well as English language) during Head Start predicted both Spanish and English reading outcomes in kindergarten and 1st grade. This finding for children’s lan-

guage growth is consistent with the interpretation that growth in Spanish relates positively to learning to read in English, Hammer said. The findings contradict research with older school-age populations, however, for whom the results have been mixed. Demographic and language differences across the populations studied might explain the differences, Hammer said. Alternatively, the results may be explained by differences in methodology: Hammer measured the rate of growth in language over time in her pre-school samples whereas the studies of older children measured children’s language at one point in time. Thus, Hammer concluded, to fully understand how a first language affects developing a second language over time, more attention needs to be paid to measures of growth using longitudinal research designs.

What strategies might teachers use to promote dual-language learners’ language development in preschool? Only a few studies have addressed this question, and so little direct evidence exists, Hammer said. Three new studies funded by NICHD are being conducted at Florida State University, Temple University, and the University of North Carolina to determine the effects of various preschool curricula. Meanwhile, results from only a handful of studies are available on the possible effectiveness of preschool curricula and programs (see Hammer, 2009).

One study examined the impact of attending a bilingual preschool program on children’s Spanish- and English-language development. Compared with children at home during the day, children who attended bilingual preschools made greater gains in English skills while maintaining Spanish (Rodriguez et al., 1995). Two other studies examined the impact of curricula on language and other achievement-related outcomes. Barnett and colleagues (Barnett et al., 2008) conducted a randomized trial to evaluate the effect of the curriculum Tools of the Mind on preschoolers’ language, literacy, and social behavior. In the study sample, 93 percent of the children were Hispanic and for 63 percent of them Spanish was spoken at home. The curriculum had positive effects on such outcomes as English vocabulary and Spanish receptive and expressive language.

The curriculum Literacy Express has been evaluated in an experiment in which children were randomly assigned to a control classroom or to one of two types of instruction: an English-only version of the program or a transitional version in which Spanish instruction gradually transitioned to English (Farver, Lonigan, and Eppe, 2009). The children who received either type of instruction made greater gains in Spanish and English literacy (print knowledge and phonological awareness) than children in the control classrooms. The children in both experimental conditions experienced English vocabulary gains, but children in the transitional program had higher scores on English vocabulary definitions and print knowledge than did those in the English immersion group. In addition,

the transitional approach was the only one that supported language and literacy outcomes in both Spanish and English.

In closing, Hammer summarized several areas of research that would help to better understand dual-language learners and their progress with language, learning, and achievement. First, better descriptions of study populations and samples are needed to understand the heterogeneity of English-language learners. Better documentation of the characteristics of study samples, including information about proficiencies in all languages spoken and other characteristics, would help to interpret study findings.

Second, how early language experiences relate to reading and later achievement is not well understood: much more needs to be known about how uses of first and second languages at home affect first and second language growth. Thus, longitudinal studies of children’s language and literacy are needed to assess growth in first- and second-language and literacy proficiencies and to identify influences on their development. Third, most of the research to date has confounded language status with SES and has focused mainly on low-SES bilinguals: more research is needed that disentangles language experiences and SES.

Fourth, more second languages than Spanish need to be included in research studies to help interpret whether findings apply to the general experience of learning two languages or only to a particular language or population. Finally, intervention studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of various instructional models, curricula, and teaching techniques. Such studies should identify which approaches work best in terms of children’s language proficiencies and other characteristics. As part of this work, language facilitation strategies with evidence for their role in supporting the language development of monolinguals, such as modeling language, recasting, extending, and elaborating utterances, would be useful to incorporate into instructional approaches and to test.

INTERVENTIONS

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and Roberta Golinkoff began their comments by noting two “big ideas” in understanding reading. First, reading is parasitic on language, a point first made by Gibson and Levin (1975) and later elaborated by Hollis Scarborough (2001) who compared learning to read to weaving a rope. Learning to read involves weaving together separate strands of skill; vocabulary and decoding, for instance, are but single strands of the rope. A broader view of language and its relation to reading development is essential to, first, understand the nature of each strand and, then, decipher how the strands of the rope become woven together. Second, language learning is malleable, as shown by both home and classroom intervention research.

To develop more effective preschool interventions, Hirsh-Pasek outlined seven empirically based principles for early childhood language learning derived from the research literature and which were recently applied in developing a preschool curriculum for the state of California (California Department of Education, 2008).

-

Children learn the words they hear most often.

-

Children learn words for things that interest them.

-

Children learn best in environments that are interactive and responsive rather than passive or “repeat after me” environments.

-

Children learn words in meaningful contexts rather than in isolation.

-

Children need clear information about the meanings of words and strong conceptual understanding, which can be developed by building on what children already know, including what is known about and through other languages.

-

Vocabulary learning is intrinsically intertwined with other areas of language development, especially grammar.

-

A cornucopia of words must be learned that includes not only object words, but also words for actions, attributes, and spatial concepts.

These principles apply, Hirsh-Pasek argued, regardless of whether a child is learning a first or second language and regardless of the particular language being learned. Instructional approaches with more of these principles should result in progressively better language outcomes, she predicted, but how to apply these principles to early childhood interventions needs to be better understood.

Hirsh-Pasek identified five “burning issues” relating to language in the early childhood education field. First, she argued, different aspects of language (phonological awareness, vocabulary, morphology, and so on) have direct and indirect effects on reading and learning. Phonological awareness is one language skill known to have a direct effect on reading achievement, but the importance of other language skills to reading are sometimes underestimated because their influence is indirect.

Second, the time has come to go beyond the general claim that more language input is always better to define which language experiences matter the most and how they have their effects: for instance, through affecting underlying cognitive processes such as faster vocabulary retrieval. As part of refining future work, the current focus on noun-based vocabulary needs to be expanded to focus attention on other aspects of language that are equally important and that can be learned, such as grammar and uses of

verbs and other words for generating complex sentences and participating in discourse.

Third, as Lesaux mentioned earlier, understanding dosage effects would help determine how much intervention is needed to see desired changes in children’s language: Are there tipping points or essential thresholds to identify? It would be helpful to be able to have enough studies on this question to be able to conduct meta-analyses to link intervention duration, type, and timing to units of outcomes.

Fourth, what is the impact of having a second language on children’s linguistic, cognitive, and reading development? As Hammer reported, the literature appears to be mixed. Hirsh-Pasek noted that some researchers, among them Laura Ann Petitto (see, e.g., Petitto and Dunbar, 2009) and Ellen Bialystok (see, e.g., Bialystok, Luk, and Kwan, 2005; Bialystok et al., 2005) have reported that a second language benefits cognitive processing (e.g., attention control) and metalinguistic skill, while other data suggest that a second language dampens vocabulary growth at least temporarily and under some conditions. One problem with interpreting the literature for preschoolers on this point is that SES has not been sufficiently controlled.

Fifth, there are remaining challenges that include discovering how to encourage teachers to implement effective interventions with fidelity and refining approaches to measurement. Should researchers develop a set of standard metrics for assessing language, literacy, and other measures? This question is critical given that findings for a particular construct, such as phonological awareness, often appear to vary depending on the measure.

Hirsh-Pasek concluded by proposing the need to reimagine language and reading instruction, especially with the increased emphasis on memorization that has accompanied implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act. In addition, since teaching is influenced by the available assessment tools, teachers could benefit from having a broader conception of language and related assessments to help develop the range of language skills needed for reading and communicating, which in turn support learning in mathematics, science, and all other subjects.

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

Mariela Paez’s response also emphasized that a focus on early language is warranted because it is vital to reading achievement, which is foundational for school success. But she cautioned that the studies reviewed for the workshop largely miss the children who do not attend preschool for a variety of reasons, and, according to data collected by

Barnett and Yarosz (2007) those are often the children who have the most to gain.

Paez agreed with Dickinson and Frieberg (2009) and Hammer (2009) that it is critical to measure natural variation in children’s learning experiences, and she also agreed that convincing evidence is accumulating to show that such factors as SES, race, ethnicity, home language and literacy environments, as well as participation in preschool, are all associated with differences in children’s language skills. It is now important to conduct research to better understand the processes by which these factors affect language and literacy and to develop interventions that can support language and literacy in schools and classrooms. Paez outlined considerations when designing such research.

First, consistent with Hammer, Paez noted the need to further specify and diversify the sample populations to better understand individual differences. Most research with dual-language learners has been with Spanish-speaking children from low-income backgrounds (Hammer, 2009). Differences within Spanish-speaking groups also remain to be explored. For instance, does a 4-year-old who attends a preschool program in California with predominantly Spanish speakers have the same kind of language experience as a child in the Northeast who attends a Head Start program with children who represent 8 or 10 languages? Research does not currently capture such nuances so their implications for language learning and achievement are not known. Large-scale studies, which are most likely to inform instructional and policy decisions, especially need to do a better job of capturing complex contextual influences on language and learning.

More work is needed to compare different groups of dual-language learners, especially in the preschool period and to replicate studies of older children with preschool students. Recent research by Bialystok and colleagues (see, e.g., Bialystok, Luk, and Kwan, 2005) compared three different groups of bilingual students—Chinese and English, Hebrew and English, and Spanish and English—to examine how aspects of language development transfer across languages; and the work took into account the unique social and cultural contexts of each group. Such work, if replicated and pursued further with preschoolers, would lead to better understandings about how different dual-language learners develop that could be used to inform interventions and instructional approaches.

With respect to measurement and assessment, there is no consensus in the field about the best way to assess bilingual dual-language learners, and few sound measures are available for bilingual children. Various approaches could be systematically evaluated to determine which ones are most useful to pursue for research, practice, and policy, taking into consideration several factors. Because young children are experiencing

rapid growth, measures are needed to measure change, which cannot be done well with existing standard measures. In addition, the standardized measures available capture only a small part of children’s knowledge, consisting of only a few items within each skill domain. Echoing Hirsh-Pasek, Paez said that multidimensional measures of language are needed to assess not only vocabulary, but also syntactic knowledge and extended discourse skills. Research on narrative skill holds great promise, she said, and so it is important to carry out, despite the expense and time-consuming nature of collecting and analyzing narrative data. Finally, new language measures are needed not only for research purposes, but also to help teachers plan instruction.

Longitudinal research will be especially important for studying dual-language learners, according to Paez, because these children might take more time than monolingual children to develop English-language and literacy skills. Research is also needed on effective curricula and approaches to language instruction and intervention. At this time, language of instruction is a priority issue, Paez argued, and research supports using and developing children’s home languages. As discussed earlier, the research shows that Spanish instruction does not harm English-language learning and appears to benefit a range of linguistic and cognitive outcomes. An important step forward for policy could be to replicate recent work (see, e.g., Barnett et al., 2007) showing the effects of preschool two-way language programs on both English and Spanish development.

A BASE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

In her response, Jill de Villiers noted that several presenters had called attention to the need to study more diverse populations, more languages, and more aspects of language than vocabulary. These calls point to the need to be cautious about prematurely generalizing the findings available, taking care, for example, not to interpret studies focused on vocabulary as speaking to language abilities more generally, or inferring that results for decoding skills all refer to reading. Likewise it is important not to generalize results from studies of children in poverty to all language-minority children or all dialect speakers, or to generalize results for sequential bilingual children to all bilingual children, or from Spanish dual-language learners to dual-language learners in all languages.

De Villiers noted that the research reviewed had different purposes and focused at different levels of analysis, including naturalistic studies of variations in children’s early childhood environments and relations to children’s language and learning; intervention studies to evaluate instructional interactions in the classroom; intervention studies to modify parental language; intervention efficacy studies to identify the condi-

tions that influence effectiveness, and so on. All types of research efforts could be better integrated in the future to create a more coherent base of knowledge.

It will also be critical to discover how multiple levels of language are interconnected. For instance, phonological awareness contributes to vocabulary learning, but does vocabulary learning undergird phonological decoding? Vocabulary is needed to crack the code of syntax and morphology, but once syntax and morphology are mastered, they can be used to learn new words. Narrative and discourse motivate the use of syntax and morphology, but one needs good syntax and morphology to build complicated discourse. Though the precise definition of “academic language” may be debated, language used in school is densely packed text with noun-based propositions and words that present challenges because they are derivationally complex or abstract. As noted by Schleppegrell (2009), analyzing linguistic devices used to connect text could help students to unpack complex dense narrative and discourse. Yet, having some degree of skill in narrative and discourse in the first place aids in figuring out connected text.

Children encounter all of this complex interconnectedness when learning oral language and then again when learning to read, which occurs well before many of the complexities with oral language have been mastered. As a result, oral language and written language must develop in tandem. The complexity gets compounded further when young children are learning to speak, read, and write in a second language and are influenced by their level of knowledge and skill in their first-language oral, reading, and writing proficiencies.

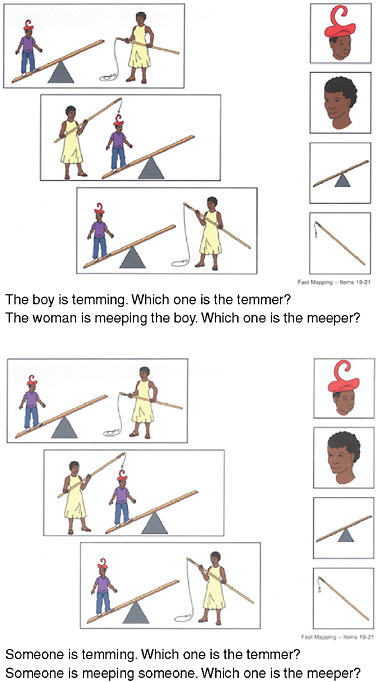

To better understand this complexity going forward, de Villiers argued for a more refined analysis of children’s grammatical development that could be used to support language and reading in school. Research on syntactic bootstrapping, for instance, has revealed how children use grammatical structure and vocabulary to comprehend oral language. De Villiers presented an example from research in which children were to figure out the meaning of two unknown words—both action verbs—read to them as they viewed pictures involving a boy and a woman depicting the actions (see Figure 3-1).

For the first picture, children are told “Look at this. The boy is temming. Which one is the temmer?” In the second picture, children are told “The woman is meeping the boy. Which one is the meeper?” If read with the vocabulary items “boy” and “woman” removed (e.g., Someone is temming. Which one is the temmer?), the meaning becomes ambiguous. Either the boy or the woman could be doing the action: thus, knowing the vocabulary items “boy” and “woman” was needed to figure out the meaning of the intransitive form of the verb. In contrast, answering ques-

tions about the transitive form—“Someone is meeping someone. Which one is the meeper?”—can be done using information available in the syntactical structure and the pictures provided.

Models of learning that emphasize frequent exposure to language, active participatory rehearsal, and elaborative rehearsal to connect what is to be learned with what a child already knows have been around for a century and are rather primitive for the task at hand, in de Villiers’ view. More than 40 years of research has accumulated about children’s grammar development that could be used to build a more precise science on the linguistic supports that help students learn aspects of language used in academic settings. More exact models of the way children parse new linguistic input could be articulated according to their stage of linguistic development to identify the critical ingredients to include in children’s exposure to language. The next challenge would be to convert this knowledge into deliverable educational experiences, such as creating instructional interactions and texts that can support learning.

Consider, for instance, that if 5- to 7-year-old children are asked, “How did she know where he went?” they will typically answer the “where he went” part of the question instead of the actual “how did she know” question that was asked. Young children are attracted to closing off that second clause and do not incorporate it into the entire sentence. (Interestingly, young speakers of what is commonly known as African American English do not make this error due to differences in grammatical patterns.) It is not known whether children make this error with reading. This example shows, de Villiers argued, that to better understand the relationship between oral parsing strategies and parsing strategies used in reading print, research is needed to determine how what is known about the development of children’s grammatical competencies might be used to help guide reading instruction and other academic uses of language.

De Villiers cautioned, however, that several questions remain about the learning conditions for complex language:

-

How much does sheer frequency of exposure help language learning? Does the importance of frequent exposure fade over time? For instance, second-language learners have particular difficulty with such structures as gendered articles, noun-verb agreement, and other “empty forms” that native-language learners develop quickly and easily. De Villiers speculated that frequency of exposure as a mechanism for learning may become less important if these forms are not essential for communicating meanings needed for learning academic content, or because there is a critical period for learning these forms so that no amount of exposure will help.

-

Could the effects of exposure differ for vocabulary and grammatical structure? Perhaps repetition helps to learn words but not grammatical structure.

-

When does variegated experience matter most? For instance, multiple frames are known to help with learning verbs, and the importance of variegated experience has been corroborated in Schleppegrell’s work (see Schleppegrell, 2009) on academic text showing that rephrasings that offer multiple exposures to words in multiple contexts aids learning.

-

When is it helpful or even necessary to experience linguistic contrasts: two sentences next to one another with a tiny structural difference that makes a significant difference in meaning?

-

When is it necessary for the content to be interesting? Might cultural background affect what is found to be interesting?

To broaden the options young children have to hear and respond to more “interesting” and important language, de Villiers argued for designing children’s books with the dual purpose of providing content and featuring linguistic contrasts. Is it possible to create academic texts that present curriculum-based content with this kind of embedded linguistic quality, and if created, would they facilitate second-language learning? Software, de Villiers suggested, is another unexploited resource for linguistic interventions. Instead of the usual trial-and-error problem solving in adventure games, players might be asked to solve linguistic puzzles en route.

Moving forward, de Villiers offered several items to consider with respect to the broader context of language learning. First, what might the ideal balance be between implementing universal approaches for developing language and strategies that consider individual language uses in particular communities? Second, if school doesn’t “feel or sound like home” to students, is it important to focus on changing the schools that children enter as much as the homes they come from? One might even ask, despite the clear importance of language to schooling, whether language is the most urgent problem to address in schools for narrowing achievement gaps. Certain practices in classrooms and schools, some of which occur disproportionately in low-income preschools, may affect learning more than finding better ways to teach vocabulary, for instance. Finally, certain dialects or languages often are not seen as bringing “cultural capital” to school learning, and de Villiers expressed her agreement with other participants that there could be benefits to raising the perceived value of the languages and language variations that children bring to school as part of creating environments that are supportive of learning.

DISCUSSION

Environmental Factors

Under the right circumstances, Fred Genesee stressed, learning a second language is not particularly challenging for most young children. The differences and lags reported by Hammer (2009) for early dual-language learners, he noted, are not “natural”—they are not inherent in the child or an inevitable trajectory in the process of learning two languages. Rather, evidence has accumulated to suggest that these variations are due mainly to environmental factors, such as the age of onset in learning a new language, the amount of exposure, and type of exposure to language. One such environmental factor is whether two languages are learned simultaneously from birth or are learned sequentially. With the possible exception of vocabulary, monolingual children and children who learn two languages simultaneously, given sufficient input in both languages, develop similarly. And it is known that vocabulary can continue to grow, unlike grammar, which may be constrained by a critical period. Moving forward, a more fine-grained understanding is needed, he proposed, regarding exactly what learning outcomes can be expected under more precisely defined learning conditions.

Lesaux agreed, saying that her data support this argument since Spanish-speaking English-language learners showed the same rates of vocabulary growth as English-only speakers. Moreover, the quality of instruction was an environmental factor that made it difficult for all bilinguals to catch up to monolingual norms. Hammer concurred, and reiterated that the growth rates for English vocabulary among bilingual children were not flat in her research: rather, bilingual children gained on monolingual peers, with children who were exposed to English before Head Start gaining the most (Hammer, 2009).

Test Uses and Limitations

William Labov noted contradictions in the previous panel discussion regarding the relationship of SES to language growth. Several participants, he noted, have emphasized the importance of valuing the languages and variations that low-income African American or Latino children bring from their home communities. Yet, data presented in the first panel, derived mainly from standardized tests, clearly show impoverished language that could be considered a deficit. Labov asked David Dickinson to address how these two views might be reconciled.

Dickinson responded that, in his view, the contradiction lies in what the language is needed for: the purpose or task that drives expectations for language outcomes. Some children from low-income backgrounds have

weaknesses in some aspects of language (particularly receptive vocabulary as measured by the Picture Peabody Vocabulary Test [PPVT]) that predict reading and achievement in other academic areas. Another related question is how curricula might be designed to build on the language strengths that researchers are documenting. A good example is the expressive discourse of children from families such as those in Vernon-Feagan’s research (e.g., Vernon-Feagans, 1996; see also Chapter 2) that are both low income and African American.

Otto Santa Ana asked why the PPVT is used in much of the language-development research presented by Dickinson and Freiberg (2009), Hammer (2009), and Lesaux (2009), and about the evidence for its validity: Should findings for the PPVT be “taken with a grain of salt?” De Villiers said that it is not adequate to assume that the PPVT is a valid measure just because it results in normal statistical curves for subgroups given that African American children score consistently below the mean of other English speakers.

De Villiers described a new measure she has developed, the Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variance (DELV) Screening Test, which includes three indices of semantic development intended to substitute for an acquired vocabulary. It was designed to create contexts in which African American dialect users and English learners in the 4- to 10-year-old range perform identically to English-only speakers of standard English, while correctly identifying children in all of these groups with diagnosable language disorders. The first measure assesses whether children learned a new verb from a sentence context, as illustrated in de Villiers’ presentation. A second measure assesses contrasted vocabulary. For instance, children are shown a picture of a man coming down stairs on his hands and knees and are told, “This man is not walking down the stairs. He is….” Children must come up with a contrasting word or phrase. The third measure assesses understanding of quantifiers.

It is difficult to check the educational validity of these new measures, de Villiers explained, because with constraints on the number of measures that can be included in a single study, most researchers choose to be able to compare their results to previous work and especially with large-scale studies that have used the PPVT. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek agreed this was her experience with selecting measures for the Early Child Care Study for NICHD.

Dickinson noted that the PPVT-4, the most recent version, is reported to have fewer cultural bias problems than the PPVT-3. But de Villiers responded, the approach remains noun based, and noun use probably differentiates children the most, she speculated, because it reflects one’s experiences, such as visits to zoos and museums; in contrast, verbs are everywhere and everyone uses them. Santa Ana suggested breaking the

current approach by not using measures that have been shown to be biased and invalid and moving forward with alternative approaches.

Erica Hoff cautioned, however, about discarding tests such as the PPVT that predict academic achievement. There are many reasons that children from different backgrounds perform differently: they may hear a different language at home or a different language variety. The assessment is not intended to measure a person’s capacity to learn. A better approach would be to dispel the misinformed notion that PPVT scores measure an ability level that is inherent in the person and cannot be changed. Biased tests can measure important aspects of oral-language facility, such as the receptive vocabulary that predicts academic achievement, but they may have features that cause children to answer questions in ways that have nothing to do with the aspect of oral language that the measure was intended to assess. So, norms must be established for different groups and used for comparisons so that instruction can meet the actual needs of different children. Otherwise, teachers and policy makers expect all children to reach test norms established with children from very different backgrounds.

As a practitioner, Susana Dutro suggested augmenting the PPVT because it is very noun based and does not assess the range of linguistic skills children need to master. Practitioners would find it helpful to be able to assess, for instance, sentence generation that obligates uses of specific verb phrases and to analyze samples of writing. Also, using multiple measures can help to reduce biases introduced by overreliance on one measure.

Dickinson pointed to the need to document how much and in what ways teachers use English, Spanish, or other languages or varieties of English such as the African American dialect, and the implications of that use for children’s language learning and achievement. In-depth studies of speech samples from classrooms would help to understand natural variations in children’s experiences in relation to language outcomes in a way that is more nuanced than the PPVT and that involves actual speech production.

Genesee followed up on Dickinson’s point to suggest that given the amount of work needed to develop valid and reliable assessments of dual-language learners’ competencies, it could be useful in the short term to create guidelines on how to assess children’s language learning when good standardized measures are not available and to point to some possible alternatives to standard assessments. Analysis of children’s speech samples may provide better estimates of language facility along a broader range of dimensions than could be assessed by simply augmenting the PPVT with another standard measure. It would also be helpful to discover at what point particular standardized tests can be used with language

learners with varying degrees of language proficiency and be confident of their validity.

Genesee and Claude Goldenberg went on to discuss the value of assessing multiple aspects of language and expanding the types of approaches used to augment widely used standard assessments, especially to obtain information about a child’s native language and to supplement the information that speech and language pathologists collect using standard assessments. Goldenberg noted, however, that the possibilities for using complementary measures in research and practice will need to be considered in relation to what is feasible given practical constraints on time and other resources.

Several participants questioned whether focusing on assessment is fruitful for addressing the issue of achievement gaps. Robert Bayley responded that it is important in at least one area: English-language learners are often misdiagnosed as having language disabilities, and states show wide disparities in the incidence of disability depending on how it is measured. In Colorado, for instance, less than 2 percent of English-language learners are identified as having language disabilities, while in New Mexico 20 percent are so identified, yet it is unlikely that this difference in the incidence of disability is real. Misdiagnosis can lead to delivering the wrong kind of instruction, which can contribute to the observed achievement gaps.

Hirsh-Pasek agreed and added that teachers use assessments to know what to target with instruction, and as a result, whatever is measured as an outcome shapes what gets taught. Broadening the assessment of language facility would focus attention on important areas, such as those needed to move good decoders to understanding the meaning of text. Dutro concurred from a practitioner perspective and noted that assessments that shed light on students’ current facility with grammar and other aspects of language can lead teachers to recognize what they need to make more explicit in their teaching or modeling of language. Different assessments can reveal that children have not mastered aspects of language that a teacher was not otherwise detecting. Assessment can also reveal strengths teachers did not know children had which, as discussed in the earlier panel, can positively influence teachers’ beliefs and expectations.