6

Standards and Regulations for Product Noise Emissions

This chapter examines national, regional, and international standards setting, regulation, and compliance testing with regard to product noise emissions and their implications for U.S. manufacturers. The industrial sectors of interest include consumer products/home appliances; computers, printers, and other information technology (IT) products; portable power generation equipment; air compressor equipment; air-conditioning and ventilation equipment; yard care equipment; small engine manufacturers; and construction equipment. These are sectors for which there are significant variations in national and regional standards and regulation of noise emissions. Airplanes and road vehicles are not addressed in this chapter, since there are international bodies—the International Civil Aviation Organization for airplanes and Working Party 29 of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) for road vehicles—that deal with the harmonization of noise emission requirements for these vehicles worldwide.

Over the past two decades Europe has been particularly active in the development of product noise emission standards (e.g., voluntary limits that have been agreed upon by a nongovernmental body), regulations (e.g., noise measurements that must be complied with and certified), and efforts to increase the amount of information provided to consumers with respect to product noise emissions, such as voluntary and mandatory product labeling requirements. During this time European standards organizations have exercised considerable leadership in international standards bodies, thereby making the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and, to a lesser extent, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) worldwide leaders in the product noise emissions standards community.

In contrast, since the early 1980s, the U.S. government’s interest in regulating product noise emissions based on evolving U.S. or international standards has advanced very little. Moreover, the participation and influence of U.S. standards organizations in the ISO and IEC in the area of product emission standards has been circumscribed by the structure and funding of U.S. standards bodies and the nature of ISO/IEC governance. America has only a single vote in ISO and IEC working groups and in the approval of standards—the same as every member country in the European Union.

European noise emission regulations are more stringent and more closely aligned with those of international standards bodies than their American counterparts, and European regulations based on these standards are more extensive than regulations in the United States. ISO standards committees have superseded many American-based standards committees and organizations that U.S. manufacturers have relied on in the past. To sell in global markets it has become increasingly important that U.S. manufacturers comply with European and ISO standards.

Different product noise emission regulations in foreign markets can drive up costs for a U.S. manufacturer seeking to sell in those markets by making compliance and certification more difficult. Adding to U.S. manufacturer’s challenges are costs not only for additional testing and documentation but also for the need to carry multiple “silencer” packages and parts inventories needed to meet the demands of multiple foreign regulations.1 If a market is too small to be worth the additional design and manufacturing costs, a company may decide not to compete there. The point is that the effect of national or regional differences in regulations can be to shut U.S. competitors out of markets.

At the same time it is important to recognize that, although more stringent noise requirements can sometimes be a burden for U.S. manufacturers, they can also encourage innovation. A U.S. manufacturer’s desire to design a low-noise machine for sale in European or world markets is a positive force that could lead to the introduction of “quiet” products into American markets and provide an incentive for manufacturers and purchasers to cooperate in “buy quiet” programs.

The remainder of this chapter provides more detailed information about international noise emission requirements, standards for noise emissions, noise emission labeling, accreditation and certification requirements, and the role of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative in compliance and enforcement issues.2

IMMISSION VERSUS EMISSION

To understand how noise standards and regulations affect the ability of manufacturers to compete in national and international markets, it is important to distinguish between noise emission and noise immission.

Standards for noise emission—the sound emitted by a product independent of its location—allow a manufacturer to make a measurement of a specific piece of equipment under specified operating conditions and report the noise level, usually in the form of a “guaranteed level.” Usually, but not always, noise emission information is reported as the A-weighted sound power level. Appendix A is a primer on quantities used in noise control and acoustics.

Requirements related to noise immission—the sound pressure level at a listener’s ear—have been promulgated to address community noise worldwide. These requirements have been summarized by the International Institute of Noise Control Engineering (I-INCE, 2009).3

DETERMINING PRODUCT NOISE EMISSIONS

A wide variety of policies, regulations, and standards on noise emissions—local, national, regional, and international—have been published, and most countries have national standards organizations. In the United States the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is the major nongovernmental organization that deals with product noise standards. In past decades the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was responsible for regulating some product noise emissions at the national level. For the purposes of this report, the most significant regional standards organizations and regulatory body for product noise emissions outside the United States are in Europe.

There are three major European nongovernmental standards organizations involved with product noise emission standards setting: the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC), and Central European Initiative (CEI). The European Commission (EC) is responsible for regulating product noise emissions throughout the European Union (EU) using standards developed by CEN, CENELEC, and CEI. The international counterparts to CEN and CENELEC are the International Organization for Standardization (ISO; http://www.iso.org) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (http://www.iec.ch), which set product noise emission standards at the international level. In this section standards-setting activities and associated regulations are reviewed as they relate to noise emissions of machinery and equipment.

Product Noise Emission Standards and Regulations in the United States

American National Standards Institute

According to its website, “The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is a private, non-profit organization that administers and coordinates the U.S. voluntary standardization and conformity assessment system.” ANSI’s mission is “to enhance both the global competitiveness of U.S. business and the U.S. quality of life by promoting and facilitating voluntary consensus standards and conformity assessment systems, and safeguarding their integrity” (ANSI, 2009).

ANSI represents the United States in the ISO and IEC. ANSI neither develops standards nor funds the U.S. standards system. Rather it accredits and audits standards-setting committees that are funded and administered by engineering and scientific professional societies, industry associations, and other nongovernmental organizations. ANSI’s activities are supported by fees from these organizations (ASA, 2009b).

When ANSI allows a standard to be called an “ANSI Standard,” it is not making a technical judgment on the standard but stating that the standard was developed in accordance with operating procedures that facilitate openness, balance, and due process, and that the standard represents a consensus among those substantially concerned with its scope and provisions. Consensus is established when, in the judgment of the ANSI Board of Standards Review, substantial agreement has been reached by directly and materially affected interests. Substantial agreement means much more than a simple majority, but not necessarily unanimity. Consensus requires that all views and objections be considered and that a concerted effort be made toward their resolution. ANSI’s approval represents approval of the process, not the content.

The most important of these organizations are the four standards committees of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) on noise, acoustics, mechanical vibration and shock, and bioacoustics. ANSI-accredited standards committees related to noise are listed in Appendix C, Part A.

Even though ANSI standards reflect a consensus and are not mandatory, the procedures or criteria in those standards may be required by law, regulation, building code, or contract in specific situations. Thus, many federal regulations reference ANSI standards.

|

2 |

Vehicle noise emissions are not covered in this chapter. The World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations, a group in the UNECE, deals with vehicle standards (UNECE, 2009). |

|

3 |

Noise immission requirements in the workplace are discussed in Chapter 4. |

Adoption of International Standards

When a standard relates to international commerce (e.g., standards for product noise emissions), international standards may be adopted. In these instances it is important that the American standard be identical (or nearly identical) to the international standard for a given product. If there is an ISO or IEC standard suitable for use in the United States and recommended by a U.S. technical advisory group (see Appendix C, p. 150), the ASA standards committees may adopt the standard as written (or with minor changes) as an American National Standard (ASA, 2009a). American standards can also be used as the basis for international standards (i.e., early versions of the sound power standards).

U.S. Regulation of Product Noise Emissions

U.S. regulation of product noise emissions is relatively limited and outdated. Following enactment of the Noise Control Act (NCA) of 1972 (codifed in 49 U.S. 4901-4918), EPA’s newly established Office of Noise Abatement and Control (ONAC) was given the authority to undertake a range of activities to reduce noise pollution. These included “identifying sources of noise for regulation, promulgating noise emission standards, coordinating federal noise research and noise abatement, working with industry and international, state and local regulators to develop consensus standards, disseminating information and educational materials,… [and] sponsoring research concerning the effects of noise and the methods by which it can be abated.” With the passage of the Quiet Communities Act of 1978, ONAC’s mandate was expanded to include provision of grants to state and local governments for noise abatement. During ONAC’s brief existence, from 1972 to 1982, when it was defunded by Congress at the request of the Reagan administration, the office promulgated only four product and six transportation noise standards and was unable to implement product labeling or the Low-Noise Emission Product Program (Shapiro, 1991).

While Congress has repeatedly refused to restore funding to EPA for its noise abatement activities, the NCA and the authority it gives to EPA to regulate noise remain in effect. Without resources to implement its mandate, however, EPA has been unable to promulgate any further product noise emission standards; and the four product noise standards it promulgated during the 1970s have not been subjected to critical evaluation since, despite advances in relevant science and technology and improved understanding of the effects of noise on people. Since 1982, EPA has also lacked the resources to participate in private standards-setting efforts or to provide technical assistance to state and local governments. (An exception is the efforts to improve the standard on the performance of hearing protective devices described in Chapter 4.) By retaining its authority under the NCA without the funding to execute it, EPA has effectively preempted state and local governments from adopting updated noise emission and labeling standards of their own for the sources and products that EPA has already regulated (Shapiro, 1991).

Product Noise Emission Standards and Regulations in the European Union

European Standards Organizations

There are several important differences between the organizations and structures of standards-setting processes in Europe and the United States. In contrast to the decentralized nature of standards bodies in the United States, European standards bodies at the national and regional (EU) levels are centralized in structure. European standards activities are organized by nation and region, whereas in the United States they are organized by sector. Standards-setting organizations are largely publicly funded in Europe, whereas they are mostly privately funded in the United States. Finally, membership in national and regional standards organizations in Europe is restricted to European entities or those that have a business interest or manufacturing presence in Europe (with the exception of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute, where participation is open to other nationals). In the United States, membership in most full-consensus standards-developing bodies is unrestricted, and in many instances membership on U.S. technical committees can be international in composition.

Similar to ANSI standards, standards of European regional and national standards bodies reflect a general consensus and are not mandatory, and the procedures or criteria in European standards may be required by European and/or national law, by regulation, by building code, or by contract in specific situations. Unlike in the United States, however, European regulation of product noise emissions based on standards developed by regional and international standards bodies has been very active and expansive in recent decades.

European Regulation of Product Noise Emissions

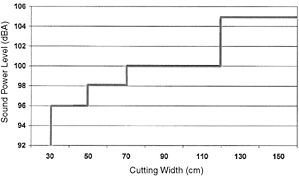

The 1996 Green Paper (EC, 1996), which stated the intent to extend the existing six directives on noise source emissions to cover more than 60 types of equipment and to require the reporting of guaranteed noise emission levels of machinery and equipment, signaled a significant change in EU noise policy (EC, 1996). One direct result of the Green Paper was the publication in 2000 of the outdoor equipment directive, 2000/14/EC (EC, 2000), and its amendment, 2005/88/EC (EC, 2005). These directives set noise emission limits on a wide variety of equipment used outdoors, such as compaction machines, tracked vehicles, wheeled vehicles, concrete breakers, cranes, welding and power generators, compressors, lawn mowers (Figure 6-1), and lawn trimmers/lawn edge trimmers. Noise emission is expressed as an A-weighted sound power level, and limits guarantee the noise emission levels of these products.

FIGURE 6-1 Permissible sound power levels (dB(A)) for lawn mowers, based on width of cut. Source: Directive 2000/14/EC of the European Parliament (EU, 2000).

The directives also set limits and require labeling of guaranteed sound power levels for a variety of other kinds of equipment, such as building-site band saw machines, chain saws, concrete and mortar mixers, conveyer belts, drill rigs, and hedge trimmers. A more detailed list and further explanation of the directives have been published by TÜV-SUD America (TÜV, 2009a). The EC also maintains a database of noise emission levels for equipment covered by the directives (EC, 2006a).

Since the 1996 Green Paper, the EC has adopted a new version of the machinery directive, 2006/42/EC, which sets standards for the safety of machinery (EC, 2006b). These standards include noise emissions, and reporting of noise emissions is required under certain circumstances:

-

The A-weighted emission sound pressure level must be reported at workstations when the value exceeds 70 dB(A).

-

The peak C-weighted instantaneous sound pressure value must be reported at workstations when the value exceeds 63 Pa (130 dB re 20 μPa).

-

The A-weighted sound power level emitted by machinery must be reported wherever the A-weighted emission sound pressure level at workstations exceeds 80 dB(A).

Alternative test conditions are allowed under certain circumstances; this means that manufacturers must know at least the emission sound pressure level and peak instantaneous level of machinery and equipment.

The EC physical agents (noise) directive sets noise immission limits for workplaces and may indirectly influence the selection of low-noise machinery in manufacturing facilities (EC, 2003). The EU has also issued a directive for noise from household appliances (86/594/EC) that allows member states to label the level of noise emissions from household appliances and establishes the A-weighted sound power level as a measure of noise emission (EC, 1986).

Noise Emission Limits in Other Countries

China has set noise emission limits (A-weighted sound pressure level) according to GB/T 7725-2004 and noise limits for room air conditioners and heat pumps. In addition, noise limits have been set on household and similar electrical appliances according to GB 19606-2004. In India, immission limits are spelled out in “Air Quality Standard in Respect of Noise.” Korea has also set noise emission limits (A-weighted sound pressure level) according to KS C9036. Japan, too, has set noise emission limits (A-weighted sound pressure level) for package air conditioners according to JIS B8612.4 Canada has a standard (CSA-Z107.58-02) on declaration of noise from machinery, but it does not set noise limits.

Sweden’s noise standard (Statskontoret 26:6) spells out noise emission requirements in terms of guaranteed sound power levels for a wide variety of IT equipment, including equipment in data-processing areas, servers, printers and imagers, laptops, data projectors, and other desktop devices. The limits and test methods specified are suitable for inclusion in purchase specifications (Statskontoret, 2004).

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION

The ISO has an International Classification for Standards (ICS). Noise emission standards fall into the following category:

|

17. Metrology and measurement. Physical phenomena |

||

|

|

17.140 Acoustics and acoustic measurements |

|

|

|

|

17.140.20 Noise emitted by machines and equipment |

A list of standards in ICS 17.140.20 can be found at http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_ics/catalogue_ics_browse.htm?ICS1=17&ICS2=140&ICS3=20.

Many ISO technical committees are involved with setting noise emission standards. One committee, ISO TC43/SC1 (noise), develops, among other standards, generic standards for the measurement of noise emissions. In the United States, ASA manages the technical advisory group for this technical committee. The ISO TC43/SC1 Secretariat in Denmark coordinates standards activities.

For the purposes of this report, the two most important series of standards are ISO 3740 and ISO 11200. The former describes the methods of measuring noise emissions from machinery in terms of sound power level, both A-weighted and in frequency bands, such as octave bands. The latter describes the measurement of emission sound pressure level. Most standards written by other ISO technical committees to determine sound power levels are similar to the 3740 series, and standards from this series (2000/14/EC and 2005/88 EC) are used by the EU in its directives on noise emissions from outdoor equipment.

The ISO 11200 series describes methods of measuring emission sound pressure levels (i.e., the level at the operator or bystander’s position measured in a controlled acoustical environment). These measurements are important in determining compliance with EU Directive 2006/42/EC, which sets emission sound pressure level requirements for machinery and equipment and, under some conditions, A-weighted sound power level according to the ISO 3740 series.

Other standards related to noise emissions have been issued by the ISO technical committee (TC) 43/SC1. These include methods of declaring and verifying noise emission values for machinery and equipment (ISO 4871) and statistical methods of determining and verifying stated noise emission values for machinery and equipment (ISO 7574, parts 1–4). In addition, there are standards for determining sound power through sound intensity (ISO 9614, parts 1–3), noise emission in the IT industry (ISO 7779, ISO 9295), and noise from rotating machinery (ISO 1680). A complete list of standards under the jurisdiction of ISO TC43/SC1 (including some in ICS 13.140, Noise with respect to human beings, and other classifications) can be found at http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_tc_browse.htm?commid=48474.

ISO TC43/SC1 also maintains relationships with a number of other ISO and IEC TCs. These include TC72/SC8—Textiles (Working Group 2 on noise), TC 117—Industrial Fans (Working Group 2 on fan noise testing), and TC 118—Compressors and Pneumatic Tools, Machines and Equipment/Air Compressors and Compressed Air Systems.

ISO TC43/SC1 is just one of the ISO TCs that issue standards related to noise emissions. Many of the committees that cover work on standards for specific types of machines have working groups related to noise standards. One benefit of this arrangement is that the committees can specify realistic operating conditions in which noise measurements should be taken and can anticipate special situations that should be accommodated. Nevertheless, the proliferation of committees greatly complicates the harmonization of measurement standards for noise emissions. A partial list of ISO TCs with an interest in noise or sound can be found in Walters5 (2007) and in this report in Appendix C.

The EU and the European standards organizations have made ISO a leader in the global standards community. Given the one country/one vote governance of ISO activities and European governments’ financial support for their national nongovernmental standards committees in ISO activities, the member states of the EU exercise considerable influence on ISO working groups. With only one vote, no public support, and only limited private-sector support for the participation of U.S. standards committees in ISO, U.S. manufacturers’ influence on ISO working groups is much less than that of its collective European counterparts.

As was pointed out in a presentation at the National Academy of Engineering workshop in June 2007, most Western countries that are members of ISO provide funding for a central standards office; national dues to ISO and IEC; funding for staff, including ISO or IEC committee secretariats and ISO working group secretariats; and funding or subsidies for travel for members of ISO working groups.6 In sharp contrast, ANSI receives no federal funding and charges its accredited standards-setting nongovernmental organizations fees to support a central standards office; national dues to ISO and IEC; salaries for staff, including ISO or IEC committee secretariats and working group secretariats; and charges for IEC working group members. This means that the United States depends on nongovernmental organizations to raise funds to support U.S. participation in international standards activities.

To influence ISO draft standards, individuals from interested countries must be present at working group meetings when decisions are made. Most product-specific noise standards rely on “basic” or “fundamental” standards developed by ISO TC43 and TC43/SC1. U.S. companies do not fund

fundamental or basic standards related to a by-product (i.e., noise) the way they fund applied standards related to a product. Thus, the United States is at a significant disadvantage in terms of representation on ISO committees involved in basic or fundamental noise standards.

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

The IEC develops and publishes international standards for electrical, electronic, and related technologies. Like ISO’s standards, IEC standards are developed by TCs with international representation. TC29, Electroacoustics, develops standards for microphones, filters, sound-level meters, hearing aids, and other electroacoustical devices. The standards produced by this committee are used in making measurements, and some modern instruments are described in Appendix E. The work of this committee is vital for the measurement of noise but will not be emphasized in this chapter. In addition, a number of other TCs have developed noise standards for specific areas, such as consumer products. Examples of IEC TCs that develop standards related to noise are listed in Appendix C, Part E. In general, IEC TCs and ISO TCs with common interests have liaison programs with varying degrees of effectiveness.

TC59 deals with standards for many products that use a common descriptor for noise emission, the A-weighted sound power level, which is not widely used in the United States. Nevertheless, if international efforts to develop a common noise label for consumer products proceed, it is likely that the sound power level descriptor will be used.

ACCREDITATION AND CERTIFICATION OF NOISE EMISSIONS

The EU Outdoor Equipment Directive (2000/14/EC) is the prime example of a noise emission regulation that requires certification of product noise levels. This directive applies to more than 50 types of equipment used outdoors, and manufacturers are responsible for initiating and completing the certification process. According to the directive, three options are available to a manufacturer that wants to document noise emission in compliance with the directive:

-

Internal control of production with assessment. The manufacturer takes full responsibility for initial certification, documentation, and ongoing monitoring of production units. A “notified body” must be contracted to verify the manufacturer’s documentation and noise-level conformance on a regular basis.

-

Unit verification. The manufacturer submits an application to a notified body, which is then contracted to examine the equipment and carry out the certification and documentation process.

-

Full quality assurance procedure. The manufacturer takes full responsibility for initial certification, documentation, and ongoing monitoring of production units. If the manufacturer has a certified quality assurance system in place, only periodic audits by a notified body are required.

A manufacturer incurs significant direct and indirect costs with each of these options. All notified bodies are based in EU countries and are approved by the EC to carry out their responsibilities; thus, U.S. manufacturers incur travel costs. These costs can be avoided, but only if the manufacturer takes on the cost of maintaining a quality assurance system, as well as noise measurement systems to monitor noise-level variances in production.

U.S. ACCREDITATION

National Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has four programs that can contribute to the development of technology for a quieter America. The National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program plays an important role in the accreditation of laboratories for noise emission measurements to meet national and international standards.

The Global Standards and Information Group provides technical information to the federal government and industry. Although there are no known activities related to noise emission accreditation, this group could become important when foreign countries seek U.S. accreditation. The National Center for Standards and Certification Information could play a role in informing American manufacturers about noise emission standards and requirements. The Calibration Laboratory for Microphones is essential for accurate noise emission measurements and noise measurements in general, and microphone calibration must be traceable to NIST.

National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program

The National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program (NVLAP) accredits laboratories in the United States and other countries for measurements according to an accepted standard. The program is established under 15 CFR 285.

The Acoustical Testing Services, one of a wide variety of available accreditation programs, includes laboratories that perform a variety of acoustical tests—mainly according to the American Society for Testing and Materials International, ANSI, and ISO standards (NIST, 2009a). These include evaluating hearing protective devices, the properties of sound-absorptive materials, sound transmission loss, and noise emissions from many sources. As of November 2008, 26 laboratories were accredited to perform measurements according to one or more acoustical standards, and, of these, 14 were accredited to perform tests according to one or more

standards for noise emissions (NIST, 2009b). These include independent testing laboratories, corporate laboratories, and one government laboratory. In addition, one laboratory is accredited in Canada and one in Japan. No list of standards has been issued for which accreditation is available. Accreditation is available for any standard—presumably from a recognized national or international standards development organization.

The procedure for accreditation includes submission of an application and payment of a fee to NVLAP, an on-site inspection by an independent technical expert, resolution of problems, and, if all problems are resolved, issuance of a certificate.

This program is not a certification of test data. It is designed to determine if a specific laboratory is qualified to perform measurements according to a specific standard or set of standards. Thus, it differs from the procedure followed by notified bodies that review data for the EU. Notified bodies examine test data for a specific product, which is (or is not) certified. Evaluations by notified bodies are based on the following international standards:

-

ISO/IEC 17025, general requirements for the competence of calibration and testing laboratories

-

ISO/IEC 17011, conformity assessment—general requirements for accreditation bodies accrediting conformity assessment bodies

Global Standards and Information Group

The Global Standards and Information Group (http://ts.nist.gov/Standards/Global/contact.cfm) is involved in international conformity and assessment activities. Although there is no known current activity related to noise emission, the mission of the GSIG is such that it could play a role in determining if noise requirements in standards or regulations are fulfilled.

National Center for Standards Certification Information

The National Center for Standards Certification Information (NCSI) provides technical information related to standards activities. Although NCSI is not involved in any activities related to noise emission, American manufacturers would benefit from a database of information on national and international standards and requirements related to noise emission.

U.S. Trade Office

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) is a cabinet-level agency with more than 200 professionals on its staff whose role is to facilitate and expand trade with foreign countries through trade agreements, trade policy, and trade dispute resolutions. The USTR reports to the president of the United States and is the president’s principal advisor, negotiator, and spokesperson on issues related to trade.

The study committee investigated how USTR might help U.S.-based companies compete more effectively in regions with noise-related regulations. Within that framework, the committee asked two questions: Can the USTR ensure that the opinions of manufacturers have an impact on the writing of regulations/standards? Can the USTR help mediate disputes over the application of regulations and standards when U.S.-based manufacturers believe they are being used to prevent them from competing in a market?

In answer to the first question, the committee found that since 1974 the USTR has had private-sector advisory committees to provide expertise in their areas (USTR, 2009). However, because noise is a by-product (usually unwanted) of the equipment being regulated, and because the measurement and reporting of noise is a complicated technical issue that applies to multiple sectors, it is difficult to present a uniform opinion that can be acted on in negotiations for trade agreements.

In fact, regulations and standards that apply to noise are developed and implemented separately from the general trade negotiations conducted by USTR. Therefore, U.S. manufacturers must be present and committed to participating in trade organizations and standards-making bodies that develop the regulations and standards for product noise levels (Schomer et al., 2008).

In answer to the second question, which may involve mediating disputes, the USTR and NIST may be in a better position to become directly involved. NIST can provide technical support to document testing and certification and can forward complaints/inquiries to USTR for notification. In addition, if a manufacturer believes that a regulation is being misapplied or is being used solely as a barrier to trade, the manufacturer can contact USTR for assistance and dispute resolution. USTR also has many interagency connections (e.g., in the U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration) that can be called on for support.

INTERNATIONAL ACCREDITATION

Two international organizations accredit laboratories: the International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation (ILAC, 2009) and the International Accreditation Forum (http://www.iaf.nu). There are also regional accreditation organizations for the Asia-Pacific region (http://www.aplac.org), the Inter-American region (http://www.iaac.org.mx), and Europe (http://www.european-accreditation.org/content/home/home.htm).

Role of Notified Bodies

The EC has defined a notified body in the following terms: “Notification is an act whereby a Member State informs the Commission and the other Member States that a body,

which fulfils the relevant requirements, has been designated to carry out conformity assessment according to a directive” (EC, 2009). The role of a notified body is to certify that the requirements of a particular directive have been met. If they have been met, CE (Conformité Européenne) marking can be put on the product.7

Of the European directives listed above (2000/14/EC, 2006/42/EC, 2003/10/EC, 86/594/EC), only the 2000/14/EC outdoor equipment directive requires that sound testing be assessed by a notified body. If an equipment manufacturer is ISO certified, it can perform sound power testing independently; the notified body audits the testing and certifies the results. Manufacturers that are not ISO certified have two options. They can have a notified body perform the required sound tests and write the reports and declaration of conformity. Or the manufacturer can perform the sound tests and have the notified body approve the resulting reports and declaration of conformity before selling the product in Europe.

Outdoor products covered by European Directive 2000/14/EC require a label of “Guaranteed Sound Power Level.” When the 2000/14/EC directive was published, TÜV SÜD America published an article, “The Father of All Noise Directives,” on the implication of this document for manufacturers” (TÜV, 2009b).

LABELING OF NOISE EMISSIONS

The term noise label can be defined as information on product noise emissions provided to final customers. The information may be on a label affixed to the product or on the packaging, in a product brochure or user’s manual, or on a manufacturer’s website. Some noise-labeling programs are mandatory, but most are voluntary. If uniform labeling appears on all products, it can be a benefit to consumers. If it is not uniform, it can create confusion and be an unfair competitive advantage or disadvantage. This section describes noise labeling in the United States, trade associations, and other organizations in the EU and other countries—including “eco-labels,” which indicate “environmental friendliness.”

Mandatory Labeling in the United States

In the late 1970s, EPA established a noise-labeling program for products (http://www.epa.gov/history/topics/nca/01.htm). However, since funding for the EPA Office of Noise Control was cut in 1981, no labels have been required for stationary noise-emitting products, with the exception of portable air compressors, which must have a label certifying compliance with the relevant EPA noise limit. Unlike other areas of the world, the United States has no other mandatory requirements for reporting noise emission values of stationary products.

Voluntary Labeling in the United States

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a database of noise information for hand-powered tools that have been tested by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH is conducting ongoing research to “fill” the database.

Sears has requirements on some but not all types of appliances; some labels include sound power values.8 Consumers Union (CU) uses a five-level pictograph scale to rate product noise for some types of products (e.g., vacuum cleaners). Details of CU testing and methods of rating are not known to manufacturers, nor are actual product emissions available.

The Institute of Noise Control Engineering has a technical committee on product noise emissions and is working to develop a simple, easy-to-understand format for noise labels. One proposal under consideration is a noise label similar to the EU energy label, which has simple graphic comparisons that enable consumers to make a quick judgment; they also provide simple numerical values for consumers who want more details.

Trade Associations and Industry-Specific Voluntary Labels

To meet growing customer demand for standardized, comparable product environmental information for IT and communications technology and consumer electronics, in 2006 IT Företagen and Ecma International harmonized their separate eco-declarations into ECMA-370 “The Eco Declaration—TED.” ECMA-370 does not include criteria, but the document enables reporting of environmental attributes, including product noise emissions. All claims in TED are subject to verification. As of 2006, more than 6,000 ecodeclarations had been issued by the predecessor organizations. The declarations are available on company websites.

The Home Ventilation Institute has administered a sound certification program for more than 35 years using a simple noise value on packaging of ventilator fans. The Air Movement and Control Association and Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Institute have “certification programs” that include published noise emission levels.

Mandatory Labeling in Europe

Several European directives and their amendments require that product noise emission values be included on product labels or in product literature. The three primary directives are 92/75/EEC—Energy Labeling for Household Appliances, 2006/42/EC—Machinery Safety Directive, and 2000/14/EC—Outdoor Equipment. The provisions of the household appliance noise directive are intended to provide consumers with information on noise in their homes, whereas the provisions in the machinery noise directive are intended to provide information on machinery that may cause hearing damage in

|

7 |

For a list of notified bodies, see http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/newapproach/nando/index.cfm?fuseaction=country.main. |

|

8 |

Vukorpa, V. 2007. Presentation at the NAE Workshop on Impact of Noise on Competitiveness of U.S. Products, Washington, D.C., June 20–21. |

the workplace. The outdoor equipment directive is intended primarily to reduce environmental noise and provide noise information to purchasers of outdoor equipment.

The EU Energy Label for household appliances is required to include sound power level values in addition to energy consumption information. Noise measurements are according to the IEC 60704 series for most appliances. The label must be prominently displayed on the product in stores and on packaging. Products with this label include refrigerators, freezers, washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, and air conditioners.

The Machinery Safety Directive requires the publication, in user documentation, of the A-weighted sound pressure level at the workstation, if the level is greater than 70 dB(A), and the A-weighted sound power level if the level at the workstation is greater than 85 dB(A). The machinery safety directive does not apply to products covered by the low-voltage directive (2006/95/EC), which does not include requirements for information on noise emissions of products, either on labels or in user information. Office and home computer products, including personal computers and printers, are not required to report noise emission values in Europe. The outdoor equipment directive (2000/14/EC) requires a simple label with the declared sound power level.

Mandatory Labeling in Other Countries

China requires noise information, either on a label or in the user’s manual, for some domestic appliances. Experience has shown that no manufacturers put this information on a label on the product. Since 2006, Argentina has required a label with noise information on some appliances. Brazil has no labeling requirements on some small appliances but requires certifiable noise values on product packaging.

The German Equipment and Product Safety Law requires publication of noise emission values for all products, including IT products—even if they are not included in the EU Machinery Safety Directive. However, because the intent of the machinery directive is to prevent hearing loss, the only requirement for most IT products is a statement that the sound pressure level emissions do not exceed 70 dB(A); this information does not describe the noise emissions of IT products used in businesses, offices, and homes.

In Germany the “GS Mark” indicates that a product complies with the minimum requirements of the German Equipment and Product Safety Act (GPSG). The GS Mark is a licensed mark of the German government and may only be issued by an accredited testing and certification agency (e.g., TÜV). Products in Germany routinely carry a GS mark indicating that they are “safe.” However, in some instances, test houses that certify GS marks require additional provisions that are not included in GPSG, and this can cause problems for manufacturers. For example, GS test houses require voltage output to personal computer and notebook computer headsets—requirements that are the same as for personal portable music systems (Walkmans, iPods, and MP3 players) without considering the differences in risk of hearing loss due to different exposure times and preferred listening levels. This unique GS requirement can act as a barrier to trade.

Voluntary Eco-Labels

Voluntary environmental labels, or “eco-labels,” signify the “environmental acceptability” of a product. Eco-labels, which are popular in many countries, include noise emission information. Although labeling or reporting product noise to customers is not required, meeting the acoustical criteria and displaying the eco-label symbol on products and in advertising implies acoustical acceptability (and possibly superiority) of the product. Some eco-label programs are the German Blue Angel (since 1977), the Nordic White Swan (since 1989), the Dutch Milieukeur, the Swedish TCO, and the EU Flower. Products with eco-labels with noise criteria include personal computers, printers, copiers, projectors, chain saws, garden tools, and construction machinery. The same issues that have been raised for other labels about uniformity of testing and verification also apply to eco-labels.

In contrast to eco-labels in other countries, the popular U.S. Energy Star program has no product noise emission criteria. EPA does, however, have the authority to label the noise emissions of products that emit noise capable of adversely affecting public health and welfare (42 USC 65, Section 4907).

Two different product groups have different ways of treating product noise emissions in the same eco-label program. During the development of the EU Flower criteria for personal computers and notebook computers, no consideration was given to noise levels that are acceptable or “green” in homes and offices. The primary consideration was an arbitrary decision that 25 percent of existing products be required to meet the new criteria. Similarly, the German Blue Angel noise criteria for personal computers are the same as for notebook computers. No consideration was given to differences in product functionality, costs of compliance, or customer expectations. At the same time, the Blue Angel noise criteria for construction equipment require only that products meet the limits set in the EU outdoor equipment directive, 2000/14/EC.

Issues and Concerns

The study committee is in favor of a uniform system for labeling the noise emissions of products. This is reflected in Recommendation 6-1 below. However, there are issues with noise labeling that need to be resolved. The major concerns about noise labels are consistency of labeling requirements and test standards (one test worldwide) and verification or consistency of testing by manufacturers. Many manufacturers have expressed concerns about favoritism and inappropriate labeling by other manufacturers, especially those in nearby countries. The lack of consistency from one product

group to another can cause confusion for customers. The lack of consistency from one country to another for the same types of products can cause problems for manufacturers who are required to perform different tests or provide different information for different countries.

Information about the availability of noise values to the public is also an issue. The public may not be aware that Web-based information, such as eco-declarations, is available. Noise information that is available only in user’s manuals or other product documentation is of no help to consumers making purchasing decisions.

The noise emission values of appliances and outdoor equipment are readily available in Europe, as required by law. However, they are not available (or not easily available) in the United States for the same products. Noise emission values for some IT products used in homes and offices are available from some, but not all, manufacturers, and they may not be readily available to potential customers.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Countries in the EU have recognized the importance of standards and taken the lead, making the ISO a leader in the standards community. ISO standards committees have superseded many American-based standards committees and organizations that U.S. manufacturers relied on in the past. America’s voice on the ISO standard committees is weakened by the lack of U.S. manufacturers’ leadership in ISO working groups. America has only a single vote, the same as every member country in the EU. The EU has been a leader in the development of noise regulations based on ISO standards. Because these regulations are more extensive than those that exist in the United States, European manufacturers have gained a competitive advantage over their U.S. counterparts in meeting consumer demand for low-noise machinery and other products worldwide.

At the time of purchase, consumers rank noise as one of the top five characteristics when comparing product performance. Other concerns are energy efficiency, cost, reliability, and serviceability. Noise levels for U.S. products are often buried in product literature and are reported using a variety of noise metrics, making it difficult for consumers to compare noise levels at the time of purchase. Thus, consumers are unable to make informed decisions about the noise emission of a product. This problem could be corrected if product noise levels were prominently displayed and manufacturers adopted a system of self-enforcement.

American manufacturers have the ingenuity to design quiet products. However, manufacturers and trade associations, as well as the voluntary standards community, have been unable to agree on a uniform standard for measuring and labeling product noise.

Recommendation 6-1: The Environmental Protection Agency should encourage and fund the development of a uniform system of labeling product noise. The system should be self-enforced by manufacturers but should have strict rules and penalties if products are deliberately mislabeled. The rules should specify standard methodologies for measuring product noise. Uncertainties in noise emission values should be acknowledged. Product noise labels should be prominently displayed so that consumers can make informed purchasing decisions. In a world with proliferating eco-labels and different requirements, international cooperation to develop one label recognized worldwide would be of great benefit to American manufacturers and consumers everywhere.

Recommendation 6-2: Government, trade associations, and industry should fund the participation of U.S. technical experts on standards bodies that develop international standards for determining product noise emissions.

Recommendation 6-3: The National Institute of Standards and Technology should take the lead in providing assistance to American manufacturers with noise regulation compliance by establishing a database of information on U.S. and international product noise emission standards and requirements.

Recommendation 6-4: To establish their credibility, organizations that determine noise emission data according to a certain standard as part of a voluntary labeling program should be accredited to test products. Managers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and its National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program should promote their accreditation program, especially in industrial laboratories.

REFERENCES

ANSI (American National Standards Institute). 2009. Mission Statement. Available online at www.ansi.org.

ASA (Acoustical Society of America) Standards Secretariat. 2009a. American National Standards Committees and US Technical Advisory Groups (U.S. TAGs). Available online at http://www.acosoc.org/standards/.

ASA. 2009b. Guide to Participation in the ASA Standards Program. Fourth Edition. Available online at http://www.acosoc.org/standards/Guide%20to% 20Participation%20-%20Updated%20June%202009.pdf.

EC (European Commission). 1986. Council Directive 86/594/EEC of 1 December 1986 on Airborne Noise Emitted by Household Appliances. Available online at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31986L0594:EN:HTML.

EC. 1996. Future Noise Policy. European Commission Green Paper. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/noise/pdf/com_96_540.pdf.

EC. 2000. Directive 2000/14/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 May 2000 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to the Noise Emission in the Environment by Equipment for Use Outdoors. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/noise/pdf/d0014_en.pdf.

EC. 2003. Directive 2003/10/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 February 2003 on the Minimum Health and Safety Requirements Regarding the Exposure of Workers to the Risks Arising

from Physical Agents (Noise). Available online at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2003/l_042/l_04220030215en00380044.pdf.

EC. 2005. 2005/88/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2005 Amending Directive 2000/14/EC on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to the Noise Emission in the Environment by Equipment for Use Outdoors. Available online at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:344:0044:0046:EN:PDF.

EC. 2006a. Enterprise and Industry: Noise 1.5. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/mechan_equipment/noise/citizen/app/.

EC. 2006b. Directive 2006/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 on Machinery, and Amending Directive 95/16/EC (Recast). Available online at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:157:0024:0086:EN:PDF.

EC. 2009. NANDO (New Approach Notified and Designated Organisations) Information System. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/newapproach/nando/.

EU (European Union). 2000. Permissible Sound Power Levels (dB(A)) for Lawn Mowers, Based on Width of Cut. From Directive 2000/14/EC of the European Parliament

I-INCE. 2009. Survey of Legislation, Regulations, and Guidelines for the Control of Community Noise. Final report of the I-INCE Technical Group on Noise Policies and Regulations (TSG 3). TSG3 Report 09-01. Available online at http://www.i-ince.org/data/iince091.pdf.

ILAC (International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation). 2009. Welcome to ILAC. Available online at http://www.ilac.org.

NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). 2009a. Overview of the National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program (NVLAP). Available online at http://ts.nist.gov/standards/accreditation/index.cfm.

NIST. 2009b. Directory of Accredited Laboratories: Acoustical Testing Services. Available online at http://ts.nist.gov/standards/scopes/acots.htm.

Schomer, P.D., G.F. Stanley, and W. Chang. 2008. Visitor Perception of Park Soundscapes: A Research Plan. Proceedings of INTER-NOISE 08, The 2008 International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering, Shanghai, China, October 26–29. Available online at http://www.internoise2008.org/ProceedingsforSale.htm or http://scitation.aip.org/journals/doc/INCEDL-home/cp/.

Shapiro, S.A. 1991. The Dormant Noise Control Act and Options to Abate Noise Pollution. Report to the Administrative Conference of the United States. Available online at http://www.nonoise.org/library/shapiro/sha-piro.htm.

Statskontoret. 2004. Technical Standard 26:6: Acoustical Noise Emission of Information Technology Equipment. Available online at http://www.statskontoret.se/upload/2619/TN26-6.pdf.

TÜV (TÜV SÜD America, Inc.). 2009a. Industries: Automotive: Noise Testing Services. Available online at http://www.tuvamerica.com/industry/automotive/noise.cfm. (See also CIMA Newsletter, June 2000, The New EC Noise Directive Becomes Effective on July 3, 2000. Available online at http://www.tuvamerica.com/tuvnews/articles/cima.cfm.)

TÜV. 2009b. Description of the Activities of TÜV SÜD America. Available online at http://tuvamerica.com/newhome.cfm.

UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe). 2009. World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations, WP.29. Available online at http://www.unece.org/trans/main/wp29/wp29wgs/wp29gen/wp29age.html.

USTR (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative). 2009. Mission of the USTR. Available online at http://www.ustr.gov/Who_We_Are/Mission_of_the_USTR.html (as posted on January 14, 2008).