5

State Data Collections

From the beginning of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), state agencies have had considerable flexibility in designing and administering the programs, and they have a mandate under the legislation to evaluate their programs. Indeed, state agencies have a multitude of responsibilities that require access to information in order to efficiently manage the programs and assess progress toward the goal of ensuring full coverage for eligible children.

This chapter discusses the motivations for state-specific surveys and summarizes information about the extent and design of such surveys. Examples are presented of the experience in two states, one with an extensive program of state-sponsored surveys and another that relies entirely on federal surveys.

MOTIVATION FOR STATE SURVEYS

Not all states conduct state surveys, but all states do have Medicaid and CHIP responsibilities that require the kind of coverage and program management information that is collected in such surveys. In her presentation to the workshop, Lynn Blewett catalogued the various responsibilities of state agencies that create a need for adequate, timely, and accessible CHIP data.

The growing and currently most critical role of the states is to facilitate implementation of access provisions in health reform. This requires information that supports programs to expand Medicaid, implement

state insurance exchange and regulation, provide for possible public plan implementation at the state level, and to implement insurance regulations, including young adult dependent coverage.

A continuing responsibility for states is to meet CHIP reporting requirements, which are largely established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). These constitute a series of annual state reports to CMS on progress in reducing the number of uninsured children, to be submitted in specified formats with data elements established in the CMS reporting programs (see Chapter 4). The requirements of the CHIP challenge, discussed in Chapter 2, now require updates with estimates of coverage on a semiannual basis.

States also have a need to effectively target outreach, enrollment, and safety net strategies. Information is needed on insurance status, age, substate geographic location, income, and race/ethnicity in order to guide and assess these activities.

And states need to prepare budgets, and, to properly accomplish the budgeting function, they need to be able to forecast activities. For the most part, inputs to forecasting models are based on expansion or contraction activities. As part of the budget process, states need to prepare and justify distribution formulas for state funds to localities, Blewett observed.

She suggested that, in order to accomplish the various responsibilities outlined above, a set series of state data requirements has evolved, generally characterized by:

-

a state representative sample;

-

a large enough sample and a sample frame that provides for reliable estimates for subpopulations including low-income children, race/ethnic groups, and geographic areas, such as county or region;

-

timely release of data, including tabulated estimates of health insurance coverage released within a year of data collection; and

-

access to microdata through readily available public-use files with state identifiers to allow states do conduct their own analysis and policy simulations.

COORDINATED STATE COVERAGE SURVEY

For the reasons given in Chapters 3 and 4, the current federal surveys and national administrative databases have not been judged sufficient to fulfill these data requirements, so states have for some time sponsored their own ongoing surveys. Blewett reported that 19 states have used an instrument called the Coordinated State Coverage Survey (CSCS), which

was developed for public use by the State Health Access Data Assistance Center at the University of Minnesota.

The CSCS is a household telephone survey designed to monitor the uninsured and provide reliable state-level insurance coverage estimates to inform state health policies. It contains a core of questions on health insurance coverage, demographics, and access to care. Some states have supplemented the survey to provide locally important data. Topics that have been added by supplementing the survey include willingness to pay (Indiana, in 2003), loss of coverage (Alabama, in 2003; Oklahoma, in 2004), dental coverage (Alabama, in 2003), attitudes toward and awareness of state reforms (Massachusetts, in 2008), and Medicare supplemental policies (Minnesota, in 2004 and 2007).

Most of the telephone surveys are conducted in a random digit dialing (RDD) mode, although several lead states are moving to dual frame surveys with cell phone samples. It has been found that, by 2009, 24.5 percent of households had cell phone–only telephone access. These cell phone–only households are significantly more likely to lack health insurance compared with households with land line telephone service. Although in the past, most states have been able to account for coverage error involving households without phone service through a weighting adjustment, it has not been possible to successfully make similar adjustments for cell phone–only households.

There are growing concerns about these state surveys. Like many other surveys, state survey managers have a concern about an overall trend toward declining response rates on the RDD surveys. The surveys are also quite costly. Blewett said that states commit between $250,000 and $500,000 on average for these surveys, with financing usually cobbled together from the state general fund, CHIP evaluation federal administrative match, conversion, and contributions from foundations.

GROWING ACCEPTANCE OF THE AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY

Although it can be assumed that states would be eager to forgo the difficulty and cost of conducting their own state survey, they have been wary of placing their trust in the federal surveys. This attitude may be changing. Since the American Community Survey (ACS) added a question on health insurance coverage and has matured and gained the credibility that comes from increasing reliability for smaller geographic areas, it is becoming a more accepted source of health insurance coverage information at the state and substate level.

Blewett summarized the state perspective on the ACS compared with the Current Population Survey (CPS). On the positive side, the ACS has a

large sample size, geographic coverage, annual estimates, and public-use files. Importantly, imputation, when necessary, is done in each state independently. The questions address point-in-time coverage and are asked of each person in the household.

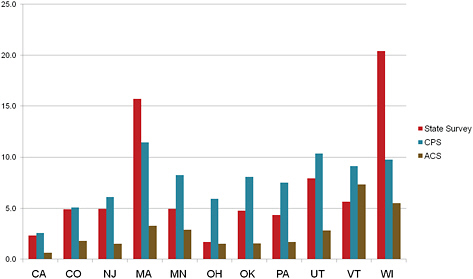

It is also becoming obvious that the ACS comes out very well in a quality comparison with both the CPS and the state surveys. As shown in Figure 5-1, the relative standard errors for the uninsurance question are smaller for the ACS in nearly every state, and they are significantly smaller in some states.

On the negative side, the ACS does not have the ability to insert state CHIP names, as the CPS now is able to do. Blewett indicated that the states need the ability to add state program names, such as Badger Care and Minnesota Care, since participants relate to those program names and may not respond correctly to a vague program description; it is a matter of accuracy, she said.

Some of the results of the ACS, juxtaposed with the prior estimates from the CPS, are troublesome to explain. In some states, the CPS rates are higher; in others, lower, and there does not seem to be a pattern to help explain the differences. It may be that the ACS data are being questioned just because they are new, different estimates and unfamiliar to audiences that are used to data from the CPS and state surveys. In addition, the ACS has no additional health status or access questions, so its ability to fully substitute for state surveys is limited.

NATIONAL HEALTH INTERVIEW SURVEY AS A SOURCE OF STATE DATA

Blewett also discussed a fourth source of state-level information—the National Health Information Survey (NHIS). The NHIS publishes health insurance coverage estimates for 20 selected large states each year. It also has the advantage of early availability of data compared with other data sources. For example, the calendar year 2009 data were available in June 2010.

But the NHIS has shortcomings as well. It does not publish data for 30 states, so geographic coverage is limited. Also, the smallest geographic identifier available on public-use microdata from the NHIS is the census region, which tends to limit state-level or subpopulation analysis. The rules placed on users of the public-use microdata mean that those wanting state-level analysis must obtain access to state identifiers in National Center for Health Statistics Research Data Centers. Although the NHIS is a rich health-related data source, with a good point-in-time health insurance question, it has limited state-level use.

As a result of the various limitations of the data available at the state level, Blewett contends, it is difficult for state analysts to pick one mea-

FIGURE 5-1 Comparison of relative standard errors for uninsurance by survey source, all ages.

NOTES: 2009 CPS-ASEC and 2008 ACS data are from public-use data. State survey data are from published reports and personal communication. Relative standard errors are defined as the SE divided by its mean.

SOURCE: Blewett (2010).

sure and stick to it. She observed that the more data-sophisticated states (about one-third of all states) use different surveys for different purposes. Although the CPS now provides the primary estimate for uninsurance when comparing across states, states with their own surveys tend to use it internally, and state policy makers have been educated on the differences across surveys. Even though the ACS is gaining popularity, many states are expected to continue to sponsor state surveys. Their policy decisions are likely to continue to rest with state survey data, for the reasons of familiarity (states are used to using state-specific data to inform policy decisions) and such features as the ability to add questions quickly that might be useful for answering state and national policy questions.

THE VIRGINIA EXPERIENCE

John McInerney provided context on the use of data in a typical state by summarizing the experience with CHIP in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Like other states, Virginia has found that managing CHIP has been a learning experience. The initial CHIP was judged to be unsuccessful—it incorporated a 12-month waiting period and covered children in families

with incomes only up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). As a consequence, the program was redesigned in 2001 to include 12-month continuous eligibility, coverage offered up to 200 percent FPL, a reduced waiting period, and a name change to FAMIS (Family Access to Medical Insurance Security). Initially, the change was successful.

As FAMIS grew, the rate of uninsured children decreased in Virginia between 2000 and 2004. However, as measured by survey data, that progress was reversed between 2004 and 2006. Incredibly, FAMIS enrollment continued to grow, but an increase in uninsured children was registered in survey data. The uninsurance rate measured by the CPS and the ACS continued to be high in 2007 but saw a slight decline in 2008, consistent with a modest increase in the FAMIS/Medicaid enrollment in that year but inconsistent with the fact that 2008 was a year of rising unemployment. McInerney pointed out that these apparent anomalies have been difficult to explain to nontechnical audiences.

As a state that has only rarely produced its own survey (the last state survey was in 2004), Virginia analysts and advocates will continue to rely on national survey data for state-level analysis. Analysts are looking forward to the increasing availability of county-level data that will come with the ACS, since Virginia has different economic conditions by region, and foundations and direct service providers want more localized data. They have not been able to get much access to county counts in Virginia because state privacy policies constrain the state from releasing county enrollment data for Medicaid and FAMIS.

THE MASSACHUSETTS EXPERIENCE

Unlike Virginia, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has heavily invested in sponsoring state-specific surveys. In her presentation, Sharon Long discussed two state-specific surveys in Massachusetts—the Massachusetts Health Insurance Survey (MHIS) and the Massachusetts Health Reform Survey (MHRS). She compared estimates of uninsurance rates for Massachusetts across state-specific surveys and national surveys and summarized lessons learned from the two Massachusetts surveys.

The motivations for the Massachusetts surveys were similar to those reported by Blewett for states that have elected to sponsor their own surveys. One motivation was the potential for larger state sample sizes, both overall and for key population subgroups and substate geographical areas, so details not available from the national surveys could be produced. Likewise, in embarking on an ambitious change in health care policy, there was a need for information on Massachusetts-specific insurance and health care programs. The needed information included information on insurance coverage, but it extended beyond that to information

about health care access and use, costs, quality, barriers to care, awareness of reform, and attitudes toward the reforms being initiated. The health care agencies in Massachusetts also needed more timely access to data to track reform and inform policy and program design than was possible with national surveys. Massachusetts judged that the ACS, which provides a much larger sample size for Massachusetts than is available from any other survey, does not address the other needs—state-specific insurance coverage options in the survey questions, information on health care outcomes beyond insurance coverage, and more timely data.

Massachusetts Health Insurance Survey

The MHIS is sponsored by the Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. It began about the time that CHIP was initiated in 1998 and was redesigned in 2008 to expand the survey sample frame to include all residential households (not just those with a land line telephone) and to modify the questionnaire to collect more of the health insurance and health care options in the state in response to health care reform changes.

The current survey consists of a sophisticated dual sample frame to capture cell phone–only households with both RDD telephone and address-based (AB) samples. There are multiple survey modes—mail, telephone, and web. The survey questionnaire is in three languages—English, Spanish, and Portuguese. It goes to 4,000 to 5,000 households each year, collecting data on health insurance coverage, health care access and use, health care costs, and attitudes toward health reform.

Long reported that external data sources are used to obtain as much contact information as possible for addresses in the RDD sample and phone numbers for the AB sample. Similarly, the survey offers multiple survey modes to as many as possible—mail, telephone (call in and call out), and web. The design is summarized in Table 5-1.

Massachusetts Health Reform Survey

The Massachusetts Health Reform Survey is sponsored by the Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation, with support in initial years from the Commonwealth Fund and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. It was initiated in 2006 in an effort to track the state’s health reform initiative. The design is an RDD telephone sample, with questionnaires like the MHIS in three languages—English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Fielded in the fall of each year, the survey sample is 3,000 to 4,000 nonelderly adults each year. Some groups (low- and moderate-income adults and uninsured adults) are oversampled. It provides information on

TABLE 5-1 Characteristics of the Random Digit Dialing and Address-Based Samples by Mode

|

Mode |

Random Digit Dialing Sample |

Address-Based Sample |

||

|

With Known Address (43%) |

Without Known Address (57%) |

With Known Phone Number (83%) |

Without Known Phone Number (17%) |

|

|

Web |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

|

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Call in to a toll-free number |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Outbound call by the survey firm |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

SOURCE: Long (Chapter 12, in this volume). |

||||

health insurance coverage, health care access and use, health care costs, attitudes toward health reform, and health plans.

Long compared the results of the state surveys with the CPS, the NHIS, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System1 in 2006, prior to the passage of health care reform and the redesign of the MHIS, and concluded that each produced a very different estimate of the uninsurance rate for Massachusetts. The three surveys that provided estimates for children (CPS, NHIS, and MHIS) had uninsurance estimates that ranged from 2.5 percent (MHIS) to 7.1 percent (CPS). These differences were traced to several factors, such as differences in the sample populations included in the surveys, differences in the wording of the insurance questions asked in the surveys, differences in question placement and context, differences in survey design and fielding strategies, and the survey time frame. Importantly, the surveys conducted in 2008, after health reform, showed low rates of uninsurance among children, with the CPS estimating that 3.4 percent of Massachusetts children were uninsured in 2008, compared with an estimate of 2.1 percent in the ACS and 1.2 percent in the MHIS.

Long drew several lessons from the rather extensive Massachusetts survey experience. She observed that state surveys have been essential for timely feedback on the impacts of health reform in a period of rapid state and national policy development. Yet both of the Massachusetts surveys

have faced challenges. It is difficult to maintain funding over time, which means, for example, that it was necessary to make decisions on survey design with little research on survey methods because of shortage of funds to support that basic research. In the end, Massachusetts obtained useful information, but it was in isolation. Analysts need comparisons with other states for context and to support stronger evaluation designs.

Despite the relatively successful experience with state surveys in Massachusetts, Long contended that federal surveys are still needed. She made several recommendations of ways to make federal survey data more useful: (a) provide much larger state and local area samples, both overall and for key population groups (including children); (b) make state identifiers available outside of research data center settings; (c) add more geocoding of state and local areas; (d) for the ACS, add state program names to health insurance questions; (e) expand survey content to include questions on access, use, and costs of care, along with other issues of relevance to national health reform; and (f) make data files available more quickly and in user-friendly formats to facilitate their use by state analysts.