3

Communicating During a Crisis

The Commercial Mobile Alert Service (CMAS) is currently being developed to leverage communications technology for communicating with the public in a crisis. In the workshop session on messaging, risk communications, and risk perception, Timothy Sellnow, University of Kentucky, and Matthew Seeger, Wayne State University, examined what is known about communicating risk and the relationship between message content and public response. They also considered what the implications might be of using as brief a message as a 90-character text message—the maximum allowed for a CMAS message.

In the next workshop session, Technologies for Alerts and Warnings: Past, Present, and Future, Robert Dudgeon, San Francisco Department of Emergency Management; Jennifer Preece, University of Maryland; and David Waldrop, Microsoft, Inc., considered the role of social networks in alerting and warning. Nalini Venkatasubramanian, University of California, Irvine, then discussed future alerting technologies.

The two sessions were moderated by Brett Hansard, Argonne National Laboratory, and John Sorensen, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, respectively. This chapter provides an integrated summary of the presentations and the discussions that followed, organized by topic.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION VERSUS RISK COMMUNICATION

In a simplified model, there are three stages in a crisis event—the stages (1) before the crisis, (2) during the crisis, and (3) after the crisis.

Risk communication, which centers on what is known about potential risks and possible responses, functions primarily in the stages before and after a crisis. Before a crisis, the goal is to educate and engage with the public and just before the crisis to issue warnings. After the crisis, the goals shift to applying lessons learned during the crisis and to building resilience from future events.

Crisis communication, by contrast, occurs in stage 2, during the crisis, and has very specific communications demands. Crisis communication inherently involves many acknowledged unknowns in the context of a particular event. Thus, an approach that is successful for risk communication may not succeed during a crisis.

During a crisis situation, communication with the public shifts from a dialogue about potential risks to instructional messages focused on the steps that members of the public should take to protect themselves (for example, evacuating or sheltering in place). Another aspect of response management involves connecting with others—individuals trying to connect with one another, such as families seeking to reunite, and emergency responders from a variety of agencies needing to connect with others in order to coordinate response efforts.

OLD MEDIA VERSUS NEW MEDIA

The traditional view of information dissemination centers on the command post. Alerts and warnings are prepared by public officials, media receive their information from briefings by public information officers (PIOs), and the public receives its information from the media. According to the traditional view, the perception of the crisis is tightly controlled by the context of the briefing room and the information that the PIO chooses to provide. Likewise, information is mediated, the timing of the information is very controlled, and direct access to the crisis zone is controlled. Regardless of which news source people turn to, they receive much the same information.

Today’s media can provide unfiltered, more-immediate information. Long before an alert is delivered by CMAS or another official source, information about the event will most likely already be available on social media sites, such as Twitter or Facebook, that support online social interaction, including the widespread sharing of people’s observations about current events. Information shared using these tools, or even information simply exchanged among individuals, includes not only text but images and video, which are readily captured using mobile telephones. As a result, those directly affected by a disaster can also become key sources of information about the event. These tools also change conventional news gathering—reporters can use cell phones

to interview people at the scene of an event or to gather both still images and video quickly.

One potential consequence of the use of these new tools is that the personal experience of those caught up in a disaster, who may be experiencing psychological trauma and stress, can now be shared widely. Even those not physically present can vicariously experience the traumatic nature of disasters.

In contrast to conventional mass media that reach mass audiences, the new media tend to reach audiences that are more selective or limited, in the sense that the messages that these media convey are targeted to particular groups. For example, in Facebook, people see information provided by individuals or organizations that they have designated as “friends,” and in Twitter people see information provided by individuals or organizations that they “follow” (although it is also possible to search all Twitter messages based on keywords). Recipients of information may in turn re-post the information (in Twitter parlance, “retweeting”) and may provide additional information that they think will be of interest to their connections. Social media can also broaden the reach of conventional media; people commonly redistribute links to news reports about disasters.

Social media also allow a community to leverage the trust that people place in their connections. Information provided by colleagues, friends, and family may be viewed as more credible than a mass alert or a news report. Similarly, local media may have more credibility than national media do if the local media are seen as being more interested in service to their communities than in wide audience appeal.

Old and new media may also differ in their resilience in a disaster. For example, although their ability to provide mobile communications can be invaluable in a disaster, cellular networks are subject to overload, their infrastructure is subject to damage, and keeping both the infrastructure and the individual phones powered can be a challenge. Older technologies have often proven to be resilient—for example, during Hurricane Charley in 2004, a local radio station’s building was destroyed, and yet the station was operating again within 5 hours.

Finally, disasters and people’s natural desire to feel connected during such crises may prompt them to adopt additional media, both new and old. Individuals in the elderly population who may not currently have cellular telephones may come to recognize their value during a disaster, and younger people who may not currently have battery-powered radios may purchase them when they realize the potential shortcomings of the cellular network during a disaster.

USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA TO FILL COMMUNCIATIONS GAPS

In November 2007, a freighter hit the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, dumping 55,000 gallons of bunker fuel into the San Francisco Bay. Although the event was very visible and might have appeared to be a serious incident, bunker fuel floats and is relatively easy to clean up. However, because official information was not made available to the public promptly, emergency management officials quickly “lost the public information battle.” Blogs and other media began reporting inaccurate information—but these media were not being tracked by officials. Soon the reports led to unsanctioned cleanup efforts and the formation of protest rallies. Further complicating the situation, the San Francisco city government lacked the authority to close the city’s beaches even though the bunker fuel was toxic. The upshot of the situation was that the San Francisco Department of Emergency Management found itself dealing with the repercussions of a nondisaster that, despite a very successful cleanup effort, was being viewed as a disaster by the public.

This event highlights the challenges of traditional crisis communications capabilities. Traditional tools such as the Emergency Alert System, which provide for notification of emergencies via broadcast radio and television, as well as newer technologies such as satellite radio and cable television, do not appear to be useful during such events because the events themselves are generally viewed as not being serious enough to warrant the use of the traditional alert and warning tools. As far as working through the media, it can take PIOs a long time to prepare, get approval for, and deliver news releases and briefings. The city of San Francisco did have a short message service (SMS)-based alerting tool available, but here too, it would have taken a while to get a message composed and approved. More-rapid dissemination tools, including the use of social media, are being looked to as additional tools for providing more timely information in future events.

SYNERGISTIC USE OF MULTIPLE MEDIA

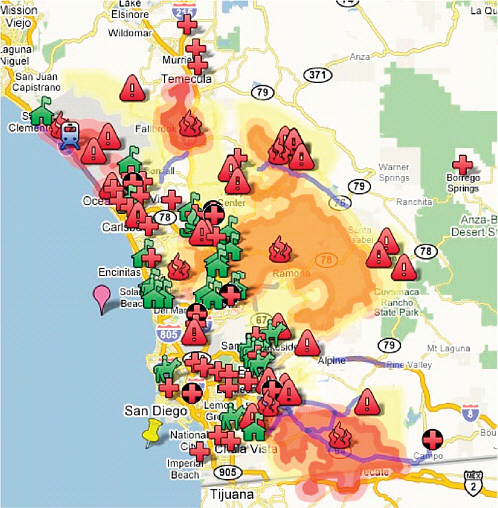

Events during the wildfires in San Diego County, California, in October 2007 provide an interesting example of how different types of media can be used synergistically. A primary driver of information during the disaster was local radio station KPBS. To complement KPBS broadcasts during the fires, station staff used a Twitter account and a Google map to provide updated information. Box 3.1 shows the Twitter stream, and Figure 3.1 shows the Google map. As the wildfires progressed, this ad hoc system emerged, providing focused information and addressing specific areas where information was missing. The Twitter content was varied—ranging from links to official government information sites to transporta-

|

BOX 3.1 Examples of Twitter Messages Following is a sample of Twitter messages sent by public radio and television broadcaster KBPS (@kpbs) during the wildfires in San Diego County, California, in 2007.

SOURCE: KPBS Public Radio @kpbs [Twitter]. Available at http://twitter.com/kpbs. |

tion information. The Google map integrated several different pieces of information into a single visual cue. The interactive map not only showed the locations of the fires but also where to find shelters, where evacuation centers were, and even where evacuees could take their animals.

INFORMATION SHARING AND GATHERING

A recent study that examined people’s use of social media in responding to the 2009-2010 H1N1 influenza outbreak found that people used social media not only to forward the official messages but also to add pointers to additional information that might or might not have been deemed reliable by health care authorities. During the initial H1N1 outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made a concerted effort not only to use multiple outlets to maximize the reach of the CDC message but also to try to ensure that CDC messages were the public’s primary source of information on the subject. To that end, CDC also used Facebook, Twitter, and other social media tools to monitor public opinion and to correct rumors. A lesson to be drawn from this experience is that although one cannot determine what information people

FIGURE 3.1 During the wildfires in San Diego County, California, in 2007, an interactive Google map provided interactive information that could be updated, on wildfire location, shelters, transportation disruptions, and other useful locations. SOURCE: Fire information posted by KPBS. © 2010 Google; Map data © 2010 Google, INEGI.

receive, it is possible to monitor the information that is being seen by the public and to reiterate key points if necessary.

A flash flood that occurred in March 2010 in San Francisco illustrates the potential for using social media to gather information about an incident. During the course of that event, emergency managers had received word from 911 telephone reports of a sinkhole at a downtown intersection. However, the severity of the event did not become fully apparent until pictures and video were posted on social media sites—in fact there

turned out to be a 20-foot geyser gushing from a manhole. Twitter and Facebook proved important sources of information on other problems such as the flooding of some San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) stations. Such reports can complement information provided by officials on the scene, who may not be able to provide reports because they are overburdened with responding to events.

Another lesson learned from the San Francisco flash flood incident is that people on the ground may be the source of both the first reports and the most detailed reports (including pictures and video)—and can make such information widely available to the public using social media. On the one hand, there are potentially significant benefits to people’s receiving such prompt and detailed information. On the other hand, there are risks that false information will be reported and spread. The net result is that social media communiqués on such incidents can both aid and complicate the task of emergency managers.

MICROBLOGGING

Users of Twitter during crises are re-posting information from traditional media, providing commentary on the event and on the public and government response, and informing their connections as to how they are themselves being affected by the event. A 2009 study of Twitter content during a crisis found that message content could be categorized as follows: 37 percent of the messages provided information (warnings, updates, answers); 34 percent were commentary; 26 percent dealt with personal impact or requests for information; and 4 percent were promotions of available media coverage or products and services.1 In addition to individuals sending messages, public officials can also make use of Twitter to reach portions of the public. Indeed, a recent study suggests that brief messages can be communicated during disasters in a highly effective manner.2

The demographics of Twitter usage differ from those for mobile phones, with a penetration rate significantly lower than the 85 percent who subscribe to cellular telephone service. Also, Twitter users tend to be younger and richer, and more of them are in nonminority populations. According to data collected in March 2010, the majority of Twitter users

are female (55 percent), between the ages of 18 and 34 (45 percent), and Caucasian (69 percent), with an income above $100,000 (30 percent).3 As a result, one would not expect Twitter to be the most effective way of reaching many of the populations known to be at most risk in a crisis.

OTHER NEXT-GENERATION CRISIS COMMUNICATION TOOLS

A number of organizations have been experimenting with a variety of new tools for emergency management. For example, Microsoft developed a prototype social network (called Vine, released as a beta in 2009, and discontinued in late 2010) especially targeted toward supporting the needs of families, other small groups, and small organizations.

One rationale behind the creation of Vine was that there are many types of disasters, on many different scales and of many different descriptions, local and global, human-made and natural, personal and societal, and only some of these emergencies require an alert to be sent by federal, state, or local governmental authorities. Events of interest only to families or other small groups can still find tools that support alerts and warnings to be useful. Another rationale behind the creation of Vine was the need for tools that support the variety of roles that individuals may play in an emergency—for example, father, husband, Red Cross volunteer, and Little League coach. Flexible tools that support each of these roles could be of considerable value.

Several years ago, researchers at the University of Maryland began designing and developing a prototype of another sort of tool, 911.gov.4 This tool was designed both to allow the public to use mobile phones and to enable the Web population to report a wide variety of incidents.5 The Web-based tools allowed users to upload photographs and videos so that emergency responders had a better understanding of what was happening at the site of a disaster. Over time, a number of cities and counties have embraced the use of mobile and Web technologies to augment traditional 911 systems.

Looking ahead, workshop participants suggested several directions for next-generation tools. These include building alerting tools that employ multiple communications channels (e.g., e-mail, Web, social networks, and mobile) and support bidirectional communications (so that recipients can send information back to emergency managers). Future tools might

|

3 |

Data available at www.quantcast.com/twitter.com. Accessed March 28, 2010. |

|

4 |

Additional information can be found at the project’s Web site, http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/911gov/. |

|

5 |

Ben Shneiderman and Jennifer Preece. “911.gov: Community Response Grids.” Science 315:944 (2007). Available at http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/315/5814/944. Accessed August 23, 2010. |

be better integrated with a user’s existing social networking tools (so that a different, unfamiliar tool need not be used in a disaster) and leveraging users’ existing social networks (e.g., also alerting, where appropriate, one’s friends or family). Such tools would reach people more effectively, provide them with more targeted information, provide emergency managers with the ability to gather and aggregate information that is relevant to the communities that they serve, and open up opportunities for the public to be more involved with their communities and government.

OBSERVATIONS OF WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS

During the presentations and in the discussion following the panel presentations, a number of observations drew on recent experiences with using social media and other communications tools:

-

Integrated systems that can easily span traditional and new communications systems will be needed to maximize the reach of alerts and warnings. For example, although cellular technology is widely used, it reaches neither everyone nor everywhere.

-

The available technologies for delivering alerts and warnings will change over time. Emergency managers will need to adapt when users shift to new tools.

-

Although social media play a growing role in disaster and crisis communications, they are not yet primary or major sources of information during a disaster; instead they serve as emerging tools that may play an increasingly important role in the future.6

-

Messages that come from local entities are generally viewed as more credible than those coming from national sources. This suggests that although CMAS messages will be routed through a national gateway, it will be useful to include the responsible local agency as part of the message.

-

Trust and credibility are affected by timing. If a CMAS alert is one of the first pieces of information received, its credibility will be higher.

-

Alerts and warnings have to be actionable and should include context—for example, why one should take this particular action.

-

Those receiving a message will first try to verify the information. Additional information sources need to be provided. If people do not

-

have the ability to obtain additional information, the effectiveness of the message will be limited. Although a “clickable” link to additional information may not be feasible (and indeed is not permitted in the initial release of CMAS), it still may be possible to reference secondary sources such as broadcast radio and television or Web sites.

-

Message testing and audience analysis will play an important role in CMAS. Post-event analysis can provide some of the best information regarding public response and the effectiveness of the messages that were sent.

-

Emergency managers or public information officers may encounter difficulties when they experiment with using social media. First, the managers’ or PIOs’ leadership may be uncomfortable with the relative loss of control with respect to how an alerting message is distributed, compared to traditional dissemination methods. Second, the information technology systems in the agency may block access to social media Web sites and services. Addressing both of these issues will require new policies that support the use of social media.

-

Communication during a crisis has benefits beyond public response. Communicating with others during crisis can be cathartic; reconstituting a sense of community is a critical function of communication systems.