Introduction:

Why Law and Why Now?

The Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health was given a three-part task by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, to address the following major topics in public health: measurement, the law, and resources. This report represents the committee’s response to its second task, which was to do the following:

Review how statutes and regulations prevent injury and disease, save lives, and optimize health outcomes. The committee will systematically discuss legal and regulatory authority; note past efforts to develop model public health legislation; and describe the implications of the changing social and policy context for public health laws and regulations.

“Law is foundational to U.S. public health practice. Laws establish and delineate the missions of public health agencies, authorize and delimit public health functions, and appropriate essential funds” (Goodman et al., 2006, p. 29). The law is one of the essential ingredients in public health practice. Two others, measurement and funding, are the subjects of this committee’s first report released in December 2010 and its third, forthcoming, report. The law is also one of the main “drivers” facilitating population health improvement. Laws, and public policy more broadly, play three roles in population health. Laws may be (1) infrastructural, referring to the statutes that describe the duties, functions, and authorities of governmental public health agencies; (2) interventional, referring to the use of the law as a tool for achieving specific health objectives; and (3) intersectoral, referring to laws enacted in other sectors of government that may or may not have health as an explicit objective, but nevertheless have effects on population health (see Moulton et al., 2003; Box 1-1).

BOX 1-1

Three Types of Public Health Law and Other Public Policy

Infrastructural: So called “enabling” public health statutes, which typically specify the mission, function, structure, and authorities of state or local public health agencies (also known as health departments).

Interventional: Federal, state, or local law or policy designed to modify a health risk factor.

Intersectoral: Federal, state, or local law or policy implemented by a non-health agency for a primary purpose other than health, but which has intended or unintended health effects.

The committee believes timing is critical to examine and make the most of the role and usefulness of the law and public policy to improve population health. This sense of urgency emerges from the juxtaposition of recent or evolving developments, as follows:

- In the sciences of public health

- In the economy (i.e., the financial crisis and the great uncertainty and severe budget cuts faced by public health agencies and by government in general)

- In the social and legislative arenas (e.g., the Affordable Care Act)

- In the functioning of public health (e.g., fragmentation of government response to public health issues, lack of interstate coordination of policies and regulations, and lack of coordination among a broad range of actors that affect the public’s health)

- In the health of the population (e.g., data on the increasing prevalence of obesity in the population and poor rankings in international comparisons of major indicators of health)

The committee’s charge specifies the review of laws and regulations, but the committee interpreted its charge broadly to include public policy in general. This is consistent with discussions of public health law in conjunction with policy elsewhere, including in the work of the Center for Health Law, Policy and Practice at Temple University and of Public Health Law and Policy, a California non-profit organization that provides tools and technical assistance to public health officials, communities, and advocates. In general, public policy refers to the broad arena of positions, principles, and priorities that inform (and constitute) decision making in all branches

of government. However, the term is also used to refer collectively to laws, regulations and rules, executive agency strategic plans, executive agency guidance documents, executive orders, and judicial decisions and precedents (see Box 1-2 for definitions of some key terms). Put simply, laws (also called statutes) are one type of public policy, but not all public policy is enacted through law. Some items of public policy are not “legal” in any meaningful sense, but may have impact that is similar to that of law in the actions they produce. Examples include policy statements, such as the recent statement of the US Department of Transportation regarding bicycle and pedestrian accommodation in transportation planning. The statement itself is not a law, but it contains a suite of recommendations for transportation agencies, and includes references to a range of pertinent statutes and regulations (DOT, 2011).

In addition to understanding the categories of law and public policy, it is useful to recognize that the processes of legislating or regulating occur in the

BOX 1-2

Defining Laws, Regulations, Statutes, Public Policy,

and Constitutional History and Judicial Precedents

Public Policy. This term refers to the broad arena of positions, principles, and priorities that inform high-level decision making in all branches of government, but is often used to refer collectively to laws, regulations and rules, executive agency strategic plans, executive agency guidance documents, executive orders, judicial decisions and precedents. Many public policies are not laws, but may have help change norms and behaviors in health.

Each branch of government—executive, legislative, and judicial—makes contributions to public policy.

Laws: Statutes and Ordinances. These are usually originated by the legislative branch of government (e.g., Congress, state senate or assembly, city council). Under the federal and most state constitutions, laws are not finalized until signed by the chief executive officer (e.g., president, governor, mayor). Laws require conformance to certain standards, norms, or procedures.

Regulations. These are rules, procedures, and administrative codes often promulgated by the executive branch of government, such as federal or state agencies, to achieve specific objectives or discharge specific duties. These are applicable only within the jurisdiction or toward the purpose for which they are made. Laws authorize administrative agencies to promulgate regulations.

Constitutional history and judicial precedents. These refer to the judiciary’s interpretation of the Constitution, laws, and regulations, including case law from prior judicial opinions.

context of a spectrum of private sector and local-level public sector policies that sometimes interact with and have effects on state and federal public policy. At one extreme are local public sector policies, such as school board decisions to source cafeteria food from a community garden. At the other extreme, there are international laws and policies that may have ramifications for U.S. policymaking, such as the International Health Regulations or the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Statutes enacted by the Legislative Branch and rule making by the Executive Branch drive policy. For example, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act and the Food Safety Modernization Act are the laws enacted by Congress to grant powers to the Food and Drug Administration to regulate (i.e., through rule-making) select products for the public’s health. Those products include human drugs, devices, tobacco, and foods not regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. However, the mere existence of legal power does not ensure public health improvement in the absence of resources and enforcement. Conversely, the absence of specific legislative power does not mean that government cannot act given that it possesses other public policy tools such as issuing guidance and implementing executive orders.

In the public sector, policy-based interventions may include health promotion such as social marketing campaigns, and awards or similar incentives for private sector policy changes. Legal or policy interventions may be highly effective. This report provides examples of areas of population health where public policy change has had significant effects in changing the conditions for health and facilitating healthier choices by communities and individuals.

The report is organized to roughly correspond to the typology described above. The second chapter focuses on laws that establish the structure, function and authority of public health agencies at all levels of government. The third chapter reviews the potential of the law (and public policy) as a type of intervention for population health improvement. The fourth chapter addresses cross-sector or intersectoral public and private policy approaches (policy decisions made in disparate fields, ranging from education to agriculture to transportation) that may affect the health of the public.

In the introduction to its first report, For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability, the committee aimed to change the terms of discourse about health. The committee wrote:

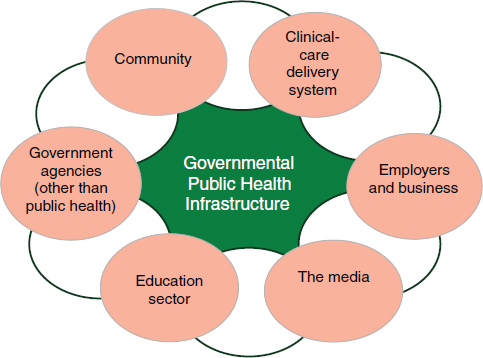

The overall public health system represented in Figure 1-1 is renamed simply the health system, with the health care delivery oval described more specifically as the clinical-care delivery system. The modifiers public and population are poorly understood by persons other than public health professionals and have made it harder to understand that public health is about the population as a whole and easier to misinterpret or overlook the collective influence and responsibility that all sectors have for creating and sustaining the conditions

necessary for health. In describing the system that comprises public health agencies, the clinical-care delivery system, communities, and other partners as the health system, the committee seeks to reclaim the proper and evidence-based understanding of health not merely as clinical care, but as the entirety of what we do as a society to create the conditions in which people can be healthy (IOM, 1988, 2011).

The present report addresses laws and public policy as they pertain to public health practice in both its institutional and programmatic aspects, and it also examines laws and public policy—and to a limited extent, policy in the private sector—as they pertain to population health more broadly. Table 1-1 provides some examples of the health-supporting policies that may be enacted and implemented by the stakeholders depicted in Figure I-1.

The major themes examined in this report include the current state of laws (infrastructural, interventional, and intersectoral) across the country and the need for both reform and improved policymaking; the implications from a public policy perspective of the public health field’s evolving understanding of the factors that create or interfere with good health; and

FIGURE 1-1 The health system.

NOTE: This figure illustrates some of the many sectors and stakeholders that contribute to population health and that may be brought to the table. The governmental public health infrastructure—agencies at all geographic levels, with their varying capabilities—stands at the center due to its special statutory role and expertise in protecting the public’s health.

SOURCE: IOM, 2011.

TABLE 1-1 Examples of Policy by Stakeholder

| Stakeholder | Policy Examples |

| Clinical care delivery system | Adopting standards to improve quality of care, providing preventive services |

| Employers and business | Providing employee wellness tools and incentives, developing policies adopting voluntary standards improving healthfulness of products |

| The media | Requiring relevant training for health journalists, formulating standards for conveying health and scientific information |

| Education sector | Adopting nutritional standards, developing and implementing physical activity guidelines for the school day, incorporating health information in the curriculum with the explicit goal of improving health literacy, making schools into community centers—supporting families, opening playing fields and playgrounds to community use (through joint use agreements), etc. |

| Government agencies (other than public health) | Implementing health in all policy approaches—considering potential health impacts of policies, adopting policies with the secondary goal of improving health |

| Community (including individuals and families, organizations, faith groups) | Advocating for healthier community environments in interactions with legislators, government executives, and private sector |

the different and sometimes conflicting sets of values and public norms that inform the availability, use, and acceptance of laws and public policy to improve public health.

In its first report, the committee made the case that the time has come for the United States to begin moving away from a primarily medical-care-oriented response to poor population health outcomes and toward a more broad-based response that engages multiple sectors and considers all the determinants of health, including socioeconomic factors. In the present report, the committee asserts that the law specifically, and public policy more generally, are among the most powerful tools to improve population health. Laws and policies undergird the practice of public health. They are responsible for many of the social and economic structures across government and society that put in motion chains of causation that contribute to health outcomes. Public policy interventions, which have been studied in selected areas of public health practice, have proven to be more effective and efficient, and offer greater value than individual based interventions in a number of circumstances. For example, counseling to prevent alcohol abuse is not very effective in the absence of policy interventions, such as

enforcement of laws, increasing taxes, and regulating alcohol outlet density. This is due in large part to the fact that health education seeks to change behaviors and lifestyles that are “too embedded in organizational, socioeconomic, and environmental circumstances for people to be able to change their own behavior without concomitant changes in these circumstances” (Ottoson and Green, 2008, p. 607). Gains in reducing tobacco use provide one of the best examples in this area.

Public health practitioners are working to employ legal or policy tools to influence physical activity, nutrition, and other behaviors by making the environment in which these occur more conducive to health-enhancing choices. Many determinants of health are not under the direct influence of public health agencies; thus action in those areas involves a variety of sectors, either catalyzed by public health’s convening role or, as is sometimes the case, by health-oriented initiatives of other actors in those sectors. Health In All Policies (HIAP) is a term that is sometimes used to describe policy action located outside the traditional domain of public health, but that considers health effects as part of the decision process. The concept of HIAP is explored in Chapter 4.

To ensure that policies are effective in improving the public’s health, policy makers must continuously evaluate their activities and investments (Council on State Governments, 2008). Results-based policies and investments are becoming apparent in the clinical care system, where the drive to increase the practice of evidence-based, high-value medicine has become pervasive. There are indications that the policymaking process can be influenced by data (Burris et al., 2010; Clancy et al., 2006). One example of the influence of evidence of effectiveness on policymaking is found in the Task Force on Community Preventive Services recommendation on laws that make it illegal to drive with blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels of 0.8 percent or higher (Shults et al., 2001). This recommendation, informed by evidence of the effectiveness of BAC laws in reducing motor-vehicle crash-related fatalities, directly led to changes in the transportation laws, which now incentivize states to enact laws lowering the BACs to secure highway funds. The Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget noted this shift in public policy, and acknowledged proof of its effectiveness (OMB, 1998). The rapidity of these changes is notable because many population-level interventions (e.g., to prevent or lower rates of chronic diseases) take years to decades to demonstrate effectiveness. Here is an example of a legal intervention that was capable of rapidly demonstrating its effectiveness in decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with motor vehicle associated injury.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act, intended to make quality clinical care services available to all Americans, also includes provisions related to prevention and population health. These components of the law are in some

ways peripheral to the law’s central purpose, but they reflect the fact that some of the discussions that led to the writing of the law revolved around health, not merely health care (Chernichovsky and Leibowitz, 2010). This represents recognition on the part of some lawmakers, advocates, and health professionals that the nation’s health problems are not just lack of access or less than optimal quality, but include far more complex challenges that explain the nation’s poor return on investment. Unfortunately, this recognition ultimately played a small role in the law itself (Gostin et al., 2011).

As the scientific understanding of the determinants of health evolves, public health professionals continue to gain insights on how the social, built, and natural environments influence health. Building on this learning is essential by applying it to the full range of population health interventions, including public policy. This must be a priority at all levels of government. That means public health statutes, which are often antiquated, need to be revisited and revised in the context of new scientific knowledge and evolving priorities in population health. This is particularly important in a time of scarce resources, when effective public policy can diminish or obviate the need for less efficient interventions (Council on State Governments, 2008). Sociopolitical currents now present both opportunities and challenges to changing public health law. On the one hand, the political environment emphasizes market forces, individual responsibility, and a perception of government interventions in health as paternalism (these issues are discussed elsewhere in the report). On the other hand, the strategic planning processes of government, including public health agencies, are more intensely focused than ever before on the need for efficiency (Millhiser, 2010). The United States makes enormous investments in health—largely clinical care services. These expenditures exceed 17 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (Truffer et al., 2010), yet they yield relatively unfavorable health outcomes for the nation. This informed, in part, the committee’s recommendation in its first report that a summary measure of population health and other sets of standard measures be adopted to help understand and convey information about the nation’s health to health professionals, policymakers, and the public.

FROM THE HISTORY OF THE LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY IN PUBLIC HEALTH

In the following section, the committee provides examples to illustrate two points: (1) the close relationship between breakthroughs in population health and public policy; and (2) the multi-sectoral history of interventions intended to address threats to the public’s health.

Public health history is full of compelling narratives about scientists, physicians, civic leaders, and others who saw the potential of public policy

to assess, monitor, and improve the public’s health. For example, William Farr was instrumental in creating a national system of vital statistics and of public health surveillance in England to inform policymakers about infectious disease outbreaks as a necessary first step in controlling them (Langmuir, 1976). Farr also demonstrated the potential of health data to test social hypotheses and use the conclusions to inform public policy, such as sanitary reforms (Whitehead, 2000). Farr’s colleague, John Snow, the public health hero who identified the source of London’s 1854 cholera outbreak, secured permission from the parish board of governors to remove the handle of the Broad Street pump (Moulton et al., 2007). Snow’s efforts contributed to the passage of laws promoting sanitary reforms—the Public Health Act in 1858 and the Sanitary Act in 1866.

Throughout its history, public health has identified health problems, their causes, and potential solutions, including legal interventions. Public health agencies, however, often lack the power to implement solutions, which often reside in other sectors of government as well as in the private and not-for-profit sectors. For example, as municipal authorities grew in complexity, different sectors assumed responsibility in arenas of population health relevance. Public health identified threats to health, but other government entities came to be charged with addressing them. Agriculture, transportation, zoning, and other government departments all play crucial roles in addressing many of the leading causes of poor health. Historically, unhygienic practices led to regulation and inspection of abattoirs by the agriculture department, safe water by civil engineers, and housing standards reflected in and enforced through building codes.

Public health practitioners have a long and rich history of engaging with other sectors and disciplines to address health challenges outside explicitly health-oriented domains. That was certainly the case in the 18th and 19th centuries, when early public health practices were developed to address industrial and occupational threats to health. It remains true in the 21st century, as knowledge of the social and environmental determinants has evolved and evidence has begun to show that solutions increasingly lie in interventions that may be undertaken in the fields of education and social services, and in planning and revenue (e.g., financial incentives) departments. Moreover, nongovernmental organizations (e.g., community and advocacy entities) play an important role in identifying threats to health, bringing them to the attention of public health agencies and policymakers, and contributing to developing and implementing solutions. One of the major challenges to putting forth public policies and laws pertinent to population health is that such actions may be incompatible with economic objectives and priorities of the marketplace. That was the case during the Industrial Revolution, where the health and safety of the workforce often came second to the engines of economic progress, and remains true today,

as, for example, businesses seek to maximize profits by both shaping and satisfying consumer desires, even when those desires detract from good health (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages, tobacco).

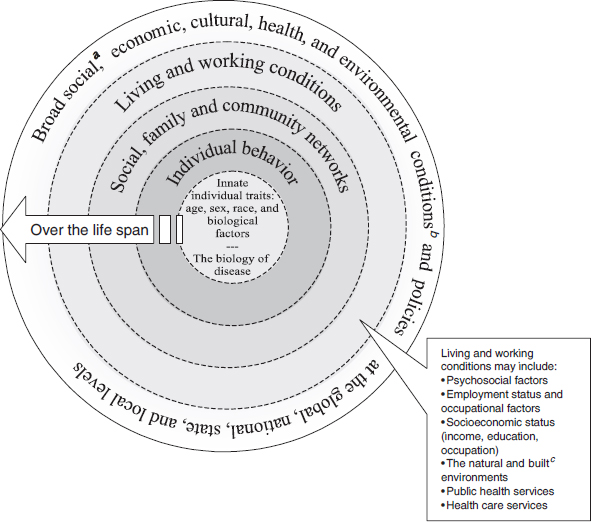

The committee’s first report introduced and discussed at length the multiple social and economic determinants that influence health (see Figure 1-2), and offered a brief overview of the evidence indicating that individual behaviors and access to clinical care account for only a part of what

FIGURE 1-2 A guide to thinking about the determinants of population health.

SOURCE: Adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991). Dotted lines between levels of model denote interaction effects between and among various levels of health determinants (Worthman, 1999).

a Social conditions include economic inequality, urbanization, mobility, cultural values, and attitudes and policies related to discrimination and intolerance on the basis of race, sex, and other differences.

b Other conditions at national level might include major sociopolitical shifts, such as recession, war, and government collapse. The built environment includes transportation, water and sanitation, housing, and other dimensions of urban planning.

c The built environment includes transportation, water and sanitation, housing, and other dimensions of urban planning.

creates population health (see Braveman et al., 2011; Cutler et al., 2006; McGinnis et al., 2002). One area of evidence on the limitations of medical care in influencing health status is found in examining socioeconomically disadvantaged populations that—even under universal medical insurance—experience worse health than their counterparts. For example, Alter and colleagues (2011) conducted a study of insured, low-income individuals in Canada’s universal medical care system, and found that they use more services and still have poorer health outcomes compared to their more advantaged peers. They concluded that countries should not rely on universal insurance alone “to eliminate the inequities that disadvantaged sectors of their populations continue to experience today. Rather, these countries need to pay additional attention to” far broader strategies to change the conditions that influence health outcomes (Alter et al., 2011, p. 281). The concentric circles in Figure 1-2 show the progression from downstream (closest to the individual’s underlying biology) to upstream (deeper social, economic, and environmental determinants, also described as the “causes of causes” of poor health outcomes).

As discussed in the pages that follow, public health attention to the more distal social and environmental determinants of health is often controversial in that it occurs against the interplay between the values of society and elected officials, and among disagreements about the ascendance of particular values. Moreover, these determinants have the longest time line and most complex—and often poorly elucidated—pathways (i.e., pathophysiologic links) from cause to effect. This presents challenges both for establishing what interventions are most effective and for compelling pertinent parties to act. The conceptual and statutory relationship to public health practice—and thus, for undertaking legal or policy interventions—is more complicated to explain and trace as one moves from the inner circles of the figure, from genetic factors and individual behaviors to the outer circles, which denote broad, high-level policies related to characteristics such as education and income.

VALUES, SOCIAL NORMS, AND THE PUBLIC VIEW OF HEALTH

Much contemporary discussion about reducing health inequalities by increasing access to medical care misses the point. We should be looking as well to improve social conditions—such as access to basic education, levels of material deprivation, a healthy workplace environment, and equality of political participation—that help to determine the health of societies. (Daniels et al., 2000, p. 6)

Discussing the law and public policy is not possible without addressing the societal context—the national and community values, norms, and popular attitudes (i.e., toward government, toward public health) and perspectives that influence American policymaking and Americans’ understanding

of the “good life.” At a time when the evidence base establishing social and environmental factors as instrumental influences to health continues to grow, four aspects of the worldview of many Americans make it difficult to operationalize this evidence in the practice of public health and of the broader health system. These include

- The rescue imperative (or the rule of rescue). People are more likely to feel emotionally moved and motivated to act in the case of specific individual misfortune (e.g., the plight of baby X highlighted on the evening news), but far less inclined to respond to bad news conveyed in terms of statistical lives (Gostin, 2004; Hadorn, 1991; Hemenway, 2010);

- The technological imperative. Cutting-edge biomedical technologies have far greater appeal (and historically, government funding) than population-based interventions, including public policies (Fuchs, 1998; Gillick, 2007; Koenig, 1988);

- The visibility imperative. Activities that occur behind the scenes, such as public health practice, remain invisible and are taken for granted in the public sphere until and unless a crisis arises, such as an influenza pandemic or radiation threats. The other contributor to the invisibility of public health is the fact that the fruits of its labors are often far in the future (Hemenway, 2010); and

- The individualism imperative. American culture generally values individualism, heavily favoring personal rights over public goods (Gostin, 2004).

On the last point, John Stuart Mill’s notions of self-regarding and other-regarding actions are useful when discussing the issues of individual freedom and the common good in the context of public health. Some individual actions primarily affect only the individual, but others have social and economic consequences (e.g., a person with infectious tuberculosis who goes untreated, a drunk driver who kills or injures others).

The mounting evidence about the most distal determinants of health calls for an examination and application of the core values of public health law, including government power and duty, the nature and limits of state power, a focus on population and prevention, community engagement, and fairness (Gostin, 2006). These values and the ways in which they appear to conflict or intersect with contemporary societal values are discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters of this report. This also has implications for the relevance and success of the committee’s recommendations.

Health is a foundational requirement for the social, economic, and political activities critical to the public’s welfare and to the strength of a nation (its governmental structure, civil society organizations, cultural life,

economic prosperity, and national security) (Gostin, 2006). For this reason, health must be a high priority for individuals and society as a whole, but getting widespread support for this position requires reframing the importance of health in achieving goals consistent with other societal values, such as prosperity, economic development, and longevity.

Alter, D. A., T. Stukel, A. Chong, and D. Henry. 2011. Lesson from Canada’s universal care: Socially disadvantaged patients use more health services, still have poorer health. Health Affairs 30(2):274-283.

Braveman, P. A., S. A. Egerter, and R. E. Mockenhaupt. 2011. Broadening the focus: The need to address the social determinants of health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 40(1, Suppl 1):S4-S18.

Burris, S., A. C. Wagenaar, J. Swanson, J. K. Ibrahim, J. Wood, and M. M. Mello. 2010. Making the case for laws that improve health: A framework for public health law research. The Milbank Quarterly 88(2):169-210.

Chernichovsky, D., and A. A. Leibowitz. 2010. Integrating public health and personal care in a reformed US health care system. American Journal of Public Health 100(2):205-211.

Clancy, C., L. Bilheimer, and D. Gagnon. 2006. Health policy roundtable: Producing and adapting research syntheses for use by health-system managers and public policymakers. Health Research and Education Trust 41(3):905-918.

Council of State Governments (CSG). 2008. State Policy Guide: Using Research in Public Health Policymaking. Washington, DC: The Council of State Governments.

Cutler, D. M., A. B. Rosen, and S. Vijan. 2006. The value of medical spending in the United States, 1960–2000. New England Journal of Medicine 355(9):920-927.

Dahlgren, G., and M. Whitehead. 1991. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Future Studies.

Daniels, N., B. P. Kennedy, and I. Kawachi. 2000. Justice is good for our health: How greater economic equality would promote public health. Boston Review (February/March):6-15.

DOT (Department of Transportation). 2011. United States Department of Transportation Policy Statement on Bicycle and Pedestrian Accommodation Regulations and Recommendations: Signed on March 11, 2010 and Announced March 15, 2010. http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bikeped/policy_accom.htm (May 19, 2011).

Fuchs, V. R. 1998. Who shall live? Health, economics and social choice. In Economic Ideas Leading to the 21st Century. Vol. 3. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific Publishing Company.

Gillick, M. 2007. The technological imperative and the battle for the hearts of America. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 50(2):276-294.

Goodman, R. A., A. Moulton, G. Matthews, F. Shaw, P. Kocher, G. Mensah, S. Zaza, and R. Besser. 2006. Law and public health at CDC.Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 55:29-33.

Gostin, L. O. 2004. Health of the people: The highest law? The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 32(3):509-515.

Gostin, L. 2006. Legal foundations of public health law and its role in meeting future challenges. Journal of the Royal Institute of Public Health 120(Suppl 1):8-14.

Gostin, L. O. 2010. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Second ed. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Gostin, L. O., P. D. Jacobson, K. L. Record, and L. E. Hardcastle. (2011). Restoring health to health reform: Integrating medicine and public health to advance the population’s well-being. Pennsylvania Law Review:1-50. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1780267 (April 8, 2011). In Press.

Hadorn, D. C. 1991. Setting health care priorities in Oregon. Jouranl of the American Mecial Association 265(17):2218-2225.

Hemenway, D. 2010. Why we don’t spend enough on public health. New England Journal of Medicine 362(18):1657-1658.

IOM (Institute of Medince). 1988. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2011. For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Koenig, B. A. 1988. The technological imperative in medical practice: The social creation of a “routine” treatment. In Biomedicine Examined, edited by M. M. Lock and D. R. Gordon. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Pp. 465-496.

Langmuir, A. D. 1976. William Farr: Founder of modern concepts of surveillance. International Journal of Epidemiology 5(1):13-18.

McGinnis, J. M., P. Williams-Russo, and J. R. Knickman. 2002. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs 21(2):78-93.

Millhiser, I. 2010. Improving Government Efficiency: Federal Contracting Reform and Other Opterational Changes Could Save Hundreds of Billions of Dollars. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Moulton, A., R. A. Goodman, and W. E. Parmet. 2007. Perspective: Law and great public health achievements. In Law in Public Health Practice, edited by R. A. Goodman, R. E. Hoffman, W. Lopez, G. W. Matthews, M. A. Rothstein, and K. L. Foster. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Moulton, A. D., R. N. Gottfried, R. A. Goodman, A. M. Murphy, R. D. Rawson. 2003. What is public health legal preparedness? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 31(4):672-683.

OMB (Office of Management and Budget). 1998. H.R. 2400—Building Efficient Surface Transportation and Equity Act of 1998. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative_sap_105-2_hr2400-h (March 18, 2011).

Ottoson, J. M., and L. W. Green. 2008. Public health education and health promotion. In Public Health Administration: Principles for Population-Based Management, edited by L. F. Novick, C. B. Morrow, and G. P. Mays. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Barlett Publishers.

Shults, R. A., R. W. Elder, D. A. Sleet, J. L. Nichols, M. O. Alao, V. G. Carande-Kulis, S. Zaza, D. M. Sosin, and R. S. Thompson. 2001. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 21(4, Suppl 1):66-88.

Truffer, C. J., S. Keehan, S. Smith, J. Cylus, A. Sisko, and J. A. Poisal. 2010. Health spending projections through 2019. The recession’s impact continues. Health Affairs 29(3):522-529.

Whitehead, M. 2000. William Farr’s legacy to the study of inequalities in health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(1):86-96.

Worthman, C. M. 1999. Epidemiology of human development. In Hormones, Health, and Behaviors: A Socio-Ecological and Lifespan Perspective, edited by C. Panter-Brick and C. M. Worthman. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 47-104.